Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Inland Container Deport ICD

Transféré par

Azlan KhanCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Inland Container Deport ICD

Transféré par

Azlan KhanDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

China

Intermodal Transport Services to

the Interior Project

(ITSIP)

Inland Container Depot (ICD)

Operation Manual

August 2003

Advisory Services To Intermodal Transport Service Providers

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION ....

I-1

A. The Role of an Inland Clearance (Container) Depot (ICD)...

I-1

1. The Container Yard Operation.

2. The Receipt and Delivery Operation..

3. The CFS Operation

I-3

I-4

B. Functions of a Container Depot..

1. To Act as a Buffer.

2. To Accommodate the Completion of Administrative and Documentary

Procedures..

3. To Assemble Outward Containers for Loading.

4. To Accommodate Unforeseen Delays

C. ICD Handling and Equipment Systems....

I-4

I-6

I-6

I-7

I-7

Lift Truck System...

Terminal Tractor/Trailers/Chassis...

Rubber Tired Gantries (RTGs) or Transtainers...

Rail Mounted Gantries (RMGs)...

Forklifts

I-7

I-7

I-9

I-9

I-10

I-11

D. Factors Influencing Choice of Best System..

I-12

II. BEST PRACTICES IN CONTAINER YARD OPERATIONS..

II-1

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

A. The ICD Layout and Area Requirements.

1. Land Area

2. Total Area Requirements Inside the ICD...

3. Total Area Requirements Outside the ICD

B. Container Yard Layout.

1. General Storage Area...

2. Special Containers and Purposes...

C. Container Handling Methods...

II-1

II-1

II-5

II-5

II-5

II-6

II-6

Tractor-Trailer System..

Lift Truck System...

Rubber Tired Gantry Crane System...

Rail Mounted Gantry Crane System...

II-8

II-8

II-9

II-12

II-14

D. Yard Address System..

II-16

E. Storage Planning and Control Procedures.

II-19

II-19

II-19

1.

2.

3.

4.

1. The Allocation of Storage Locations...

2. The Determination of Storage Space Requirements...

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

Advisory Services To Intermodal Transport Service Providers

F. Information System Applications...

II-20

G. Container Yard Operations

II-23

II-23

II-24

II-24

II-25

1.

2.

3.

4.

Inward Container Storage Operations

Outward Container Storage Operations.

In-terminal Container Movements...

Interchange Movements...

H. Managing/Controlling Yard Operations

Underlying Principles of Control of Yard Operations

Personnel Responsibilities and Functions for Control and Supervision

General Tasks Required of Control and Supervisory Staff.

Areas of General Responsibility of the Container Yard Supervisor...

II-25

II-25

II-26

II-27

II-27

III. BEST PRACTICES IN CONTAINER RECEIPT/DELIVERY

OPERATIONS

III-1

1.

2.

3.

4.

A. Principles of Receipt/Delivery Operations..

1. General Receipt Sequence for Outbound Containers.

2. General Delivery Sequence for Inbound Containers

3. Variations in Receipt/Delivery Sequences.

B. Receipt/Delivery Facilities..

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

Terminal Entrance.

Vehicle Parking Area.

Reception Office.

Offices for Agents, Customs and Other Organizations

Canteen or Rest Room.

The Gate.

Special Cargoes Gate...

In-terminal Parking Area...

Interchange Area(s)...

C. Receipt/Delivery Documentation.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

The Train Notification Order or Barge Booking List.

The Container Load List

The Container Record...

The Shipping Note.

The Delivery Order

The Collection Order.

Dangerous Goods Documents

The Equipment Interchange Receipt (EIR)

D. Receipt Procedures..

1. General Purpose Containers

2. Empty and Special Containers

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

III-1

III-1

III-1

III-2

III-2

III-2

III-2

III-3

III-3

III-3

III-5

III-5

III-5

III-5

III-6

III-6

III-7

III-10

III-12

III-14

III-15

III-16

III-18

III-19

III-19

III-21

ii

Advisory Services To Intermodal Transport Service Providers

E. Delivery Procedures.

1. General Purpose Containers

2. Empty and Special Containers

F. Managing/Controlling Receipt/Delivery Operations...

III-22

III-23

III-24

Receipt/Delivery Personnel..

Supervision of the Receipt Process

Supervision of the Delivery Process...

Completion and Shift Handover Procedures.

Supervisory Responsibilities

III-25

III-25

III-25

III-26

III-27

III-28

IV. BEST PRACTICES IN CONTAINER FREIGHT STATION (CFS)

OPERATIONS

IV-1

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

A. Functions of a CFS

1. Functions.

2. General Activities...

IV-1

IV-1

IV-1

B. Layout of Facilities

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

The CFS Entrance and Gatehouse.

The Road Vehicle Parking Area..

The Reception/Delivery Facilities for Other Transport Modes

The Reception and Administrative Office..

The Open Storage and Operational Area..

The Storage Shed..

Equipment Requirements.

IV-2

IV-4

IV-4

IV-4

IV-4

IV-5

IV-6

C. Information System and Storage Address System.

IV-6

IV-6

IV-8

1. Information System Requirements..

2. Storage Address System..

D. Procedures for Receiving, Unpacking, Storing and Release of

Inbound Cargoes in Containers...

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Preliminary and Planning Processes..

Receipt of Loaded Container from the Container Yard

Unpacking and Storage of Cargo Packages in the CFS.

Return of the Empty Container to the Container Yard.

Collection Procedures for the Discharge of Import Consignments

E. Procedures for Receiving, Storing, Packing, and Linehaul

Transport of Outbound Cargoes in Containers

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Receipt of Export Cargoes by Road Vehicle.

Planning Processes for Packing Containers.

Receipt of Empty Container from the Container Yard.

Container Packing.

Return of Packed Container to the Container Yard..

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

IV-10

IV-10

IV-10

IV-13

IV-14

IV-14

IV-17

IV-18

IV-20

IV-20

IV-20

IV-22

iii

Advisory Services To Intermodal Transport Service Providers

F. Working Practices for CFS Operations

1.

2.

3.

4.

General Rules for Storage and Stacking

Palletization.

Manual Handling

Equipment Handling..

G. Managing/Controlling CFS Operations

IV-22

IV-22

IV-24

IV-25

IV-26

CFS Personnel and Responsibilities..

The Planning Function..

The Control Function.

The Operation Function

General Supervisory Responsibilities.

IV-28

IV-28

IV-30

IV-31

IV-32

IV-34

V. BEST PRACTICES IN ICD MANAGEMENT: PERFORMANCE REVIEW

TOOL.

V-1

A. Purpose of Performance Measures and Review..

V-1

B. Types of Performance Reviews...

V-1

V-1

V-2

V-2

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

1. Operational Reviews.

2. Planning Reviews..

3. Long Term Reviews..

C. Description and Calculation of Performance Measures...

1.

2.

3.

4.

Production or Throughput Indicators..

Productivity Indicators...

Utilization Indicators..

Service Quality Indicators.

D. Corrective Management Actions.

V-3

V-4

V-5

V-8

V-9

Shift Reports and Reviews...

Daily Reports and Reviews..

Monthly Performance Reports and Reviews.

CFS Performance and Reviews..

V-11

V-11

V-14

V-17

V-22

VI ICD SAFETY & DANGEROUS GOODS HANDLING...

VI-1

1.

2.

3.

4.

A. General Safety Principles...

1. Design Principles...

2. General Safety Principles.

B. Rules of Safe Access to the ICD Working Areas.

1. Access to Restricted Operational Areas

2. Access for Operational and Engineering Reasons..

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

VI-1

VI-1

VI-2

VI-3

VI-3

VI-3

iv

Advisory Services To Intermodal Transport Service Providers

C. Working Safety and Security

1. The Container Yard...

2. The Receipt/Delivery Area...

3. The Container Freight Station..

VI-4

VI-4

VI-7

VI-9

D. Good Housekeeping

VI-11

E. Dealing with Emergencies.

First Aid...

Fire-Fighting

Emergency Rescues

Emergency Services.

VI-11

VI-12

VI-12

VI-12

VI-12

F. Dangerous Goods Handling.

VI-13

1.

2.

3.

4.

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

I.

A.

INTRODUCTION

The Role of an Inland Clearance (Container) Depot (ICD)

Inland Container (Clearance) Depots (ICDs) may be generally defined as facilities

located inland or remote from port(s) which offer services for the handling, temporary

storage and customs clearance of containers and general cargo that enters or leaves the

ICD in containers. The primary purpose of ICDs is to allow the benefits of

containerization to be realized on the inland transport leg of international cargo

movements. ICDs may contribute to the cost-effective containerization of domestic

cargoes as well, but this is less common. Container transport between the port(s) and

an ICD is under customs bond, and shipping companies will normally issue their own

bills of lading assuming full responsibility for costs and conditions between the in-country

ICD and a foreign port, or an ICD and the ultimate point of origin/destination.

ICDs are specific sites to which imports and exports can be consigned for inspection by

customs and which can be specified as the origin or destination of goods in transit

accompanied by documentation such as the combined transport bill of lading or multimodal transport document. As such, ICDs are closely associated with the promotion of

the through-transport concept. In combination with the containerization of goods, dry

ports enable the transference of goods from their place of origin to the their final

destination without intermediate customs examination; thereby intermediate handling

occurs only at points of transfer between different transport modes.

In essence, the ICD is a container depot that handles the same functions as the port

terminal except ship to shore transfer. In so doing, this allows inland bound containers

or outbound containers originating inland to bypass the port, which is generally

congested, and be processed near the shipper or consignee. Primary ports, in general,

tend to be congested and the success of the port depends on achieving quick

turnaround times for calling vessels. ICDs, whether close to the port or far away from

the port, allow cargo owners to claim their goods away from the port and port

congestion.

A standalone ICD may have many transport access and egress combinations. For

example, the ICD may be served by road, rail and/or barge. Most typically, the result is

that for inward movements of cargo, containers will arrive at the ICD via road, rail, or

barge. Once they arrive at the ICD, the containers will either be unstuffed or will

continue in container by road to their destination. For outward movements, breakbulk

goods or containers will be brought to the ICD by road and subsequently they will be

stuffed (for breakbulk goods) and depart from the ICD by road, rail or barge. Figure I-1

shows these possible combinations of transport modes.

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

I-1

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

Figure I-1: Transport Combinations for ICDs

Inward Movement

Outward Movement

Road

Rail

Road

ICD

Road

Road

ICD

Rail

Barge

Container

Barge

Breakbulk or

Container

Breakbulk or

Container

Container

Claiming a consignment can be a relatively time consuming process that involves crossborder formalities, destuffing, etc. In clearing the containers quickly through the port

terminal, the port terminal activities are roughly restricted to ship to shore transfer,

positioning in the yard for pickup, Customs detention if warranted, etc. In essence, time

consuming activities like destuffing, duty payments, cargo storage, container storage,

etc., are deferred to another location outside the port. At the completion of processing at

the container depots, the cargoes will be claimed by the owners and generally

distributed as breakbulk to their respective sites. In the case of breakbulk cargo where

the both the ICD and the cargo owner are located far away from the port, the linehaul

portion of the voyage can undertaken using containers instead of breakbulk vehicles.

Whereby breakbulk transport is much less efficient than containerized transport

generally 3 breakbulk shipments by truck is equivalent to one container shipment by

truck transport costs can be reduced by keeping the goods in containers vis--vis

breakbulk transport for as much of the linehaul component as possible. Furthermore

cargo owners are not required to send agents to the port in order to clear the goods,

rather document and cargo clearance can be undertaken at the ICD saving the cargo

owner time and money.

In the same way, export shippers can save time and money by routing their export

goods through the ICDs and avoiding the congested ports, saving on breakbulk linehaul

through containerization, and saving the cost of having agents located far away.

More specifically, the ICD performs a number of services for the transport operator and

for the shipper or consignee. In general, there are three sequences of activities:

container arrival, container storage and container departure.1 The activities that are

included in each sequence depend on the direction of the container movement

inbound or outbound and the container status FCL (no stuffing/destuffing required) or

LCL (stuffing/destuffing required). The three main operational systems in the ICD are:

The container yard operation

The receipt/delivery operation

The container freight station (CFS) operation.

This material is taken from the Port Development Programme (PDP), ILO, 1999.

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

I-2

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

1. The Container Yard Operation

The container yard operation has two major components the container storage

operation and the in-terminal container movement operation.

a) Container Storage Operation

The container storage operation is primarily is a stationary process in that

containers are placed in a container yard slot and stored until they are ready

for onward movement. The operation is concerned chiefly with keeping the

containers safe and secure. There are occasions where stored containers

need to be moved within the container stack for repositioning and for access

to other containers, however, it is good practice to keep these in-stack

movements as minimal as possible. Depending on the equipment handling

system used in the ICD, there may be equipment exclusively assigned to the

container yard, such as in the RTG and RMG systems. In these systems,

stacking and unstacking containers to/from the yard stacks to the

interchange/railhead/berth transfer equipment is considered to be part of the

container yard operation. Conversely, in a lift truck system, the lift truck is

used in the transfer process as well as the stacking and unstacking process.

In this sense, the stacking and unstacking is categorized as a step in the

transfer operation.

b) In-terminal Container Movement Operation

The other component of the container yard operation includes a range of interminal movements. These movements include: the movement of import

containers from the container yard to the CFS for unpacking, with subsequent

return of the empty containers to the empties pool; the movement of empty

containers to the CFS for packing and ensuing transfer of loaded containers to

the container yard; movements between the container yard and the customs

and port health examination areas; and intermittent movements of damaged

containers to an area set aside for container examination and repair, and their

subsequent return to container yard storage.

2. The Receipt and Delivery Operation

The receipt/delivery operation consists essentially of a linked sequence of brief

activities:

The arrival of inland transport, via the depots security entrance, at a reception

facility, where document-checking and related formalities take place.

Movement of the inland transport to a location where exchange of containers

between the container yard and transport occurs.

Departure of the inland transport from the depot, following a further set of

security and other formalities.

The two main areas of activity for the receipt/delivery operation are the gate and

the interchange areas. In the case where breakbulk cargo will arrive at or depart

the depot by a transport mode other than road, it may be necessary to have

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

I-3

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

additional receipt/delivery services located at the point of entry/exit, i.e. at the

railhead or barge berth. However, for an ICD, this is not often the case.

3. The CFS Operation

The CFS is a cargo consolidation, container packing/unpacking and cargo

distribution centre.2 In this way, shippers can transport their cargoes in break-bulk

form, by the most convenient mode available road, rail or inland waterway to

the ICD. Next, the CFS facility will arrange to consolidate and pack the goods into

containers ready for loading onward transport to a port. Similarly, buyers of goods

can arrange for the containers carrying their goods to be unpacked at the CFS,

and separated into break-bulk consignments. The buyers can then arrange for

their goods to be collected by the most convenient form of transport.

The CFS operation includes the following sequences of activities: to receive, sort

and consolidate export break-bulk cargoes from road vehicles; to pack export

cargoes into containers ready for loading aboard onward transport; to unpack

import containers, and sort and separate the unpacked cargoes into

break-bulk consignments ready for distribution to consignees; to deliver import

cargoes to the consignees transport; to store import and export cargoes

temporarily, between the times of unloading and loading, while various

documentary and administrative formalities are completed (e.g., customs

inspection, settling of charges for packing, unpacking and storage, arranging

transport).3

B.

Functions of a Container Depot

The facilities and services provided at an ICD can vary considerably. The minimum that

will exist is as follows:4

Customs control and clearance

Temporary storage during customs inspection

Container handling equipment for 20 foot or 40 foot containers

Offices of an operator, either the site owner, lessor or contractor

Offices of clearing and forwarding agents

Complete enclosure, fencing and a security system

Reliable and efficient communication facilities

Container freight station with stuffing and de-stuffing services

Statutory Authorities (i.e. Agriculture)

Shipping Lines

A more comprehensive ICD would include the above as well as some or all of the

following:

Warehouse storage including cold storage and reefer storage

PDP, ILO, 1999.

PDP, ILO, 1999.

4

Taken from Handbook on the Management and Operation of Dry Ports, UNCTAD, 1991.

3

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

I-4

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

Container storage and inventory control

Container maintenance and repair

Equipment control on behalf of shipping lines (enforcing EIR)

Offices of shipping line agents

Railway goods office

Road haulage brokerage

Cargo packing services

Consignment consolidation services

Unit train assembly and booking services

Container clearing services

Computerized cargo-tracking services

Clearing and fumigation services (atmospheric and vacuum)

Refer refrigeration points

Weigh bridges

In general, ICDs do not provide facilities for long-term storage or repair facilities for

trucks or rail wagon or locomotive maintenance. The following diagram presents a

general functional structure of an ICD.

Figure I-2: Functional Structure of an Inland Clearance Depot

Customs

Clearance

Repair

Facilities

Warehousing

Freight

Forwarding

Consolidation

Inventory

Control

Dry Port

or

ICD

Marshalling

Yard

Container

Stuffing/De-stuffing

Storage

Customer

Services

Shipping

Lines

Inland

Transportation

Source: Handbook on the Management and Operation of Dry Ports, UNCTAD, 1991.

The activities that are undertaken in an ICD ultimately depend on the type of cargo

(breakbulk versus containerized), mode of transport (road, rail, inland waterway), and

type of shipment (foreign or domestic). Certainly the movement of containers around the

ICD will require the use of handling equipment, and storage whether in a container yard

or CFS. In addition, shipments that require stuffing or de-stuffing services (breakbulk

movements) will be processed via the CFS. Likewise, foreign shipments that require

customs clearance will also be routed via the CFS.

With respect to container depot processes, the functions of container yard storage are:

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

I-5

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

To act as a buffer between road receipt/delivery and rail/inland waterway

operation.

To permit customs and other administrative and documentary procedures.

To assemble outbound containers for loading onto rail or inland waterway.

To accommodate unforeseen delays.

1. To Act as a Buffer

The use of the container yard as a buffer for operations is a main function. It acts

as a temporary storage place for containers waiting outward/inward movement.

For example, in the case of train or barge loading, it would be difficult to time the

arrival of the containers at the ICD to exactly match the loading schedule of the

train/barge. Conversely, it would be difficult to time and correctly queue the

arrival of road vehicles for picking up inward containers from an arriving

train/barge. The container yard, allows containers to be arranged in a way to

most effectively carry out receipt/delivery and loading/unloading operations.

2. To Accommodate the Completion of Administrative and Documentary

Procedures

Another function of the temporary storage afforded by the container yard is to

allow time for documents to be handled, customs clearance, health and

quarantine inspection, destuffing and various other administrative procedures to

take place without delaying train/barge or road departure. There are many

potential sources of delays that would prevent the immediate discharge or loading

of a container and so the container yard provides a holding area for containers

waiting for outstanding matters to be cleared.

In the case of imports, some of these sources of delay are:

The consignee or their bank has not received the shipping documents (bills of

lading, letters of credit, invoices).

Banks may place holds on the documents in the case that the consignee has

not made payment.

There may be delays in the issue of import licences.

Customs may not have received the necessary documentation from the

consignee.

Customs requires some time to process the documents requesting clearance.

Documents may be incomplete or inaccurate and require updating by the

consignee or freight forwarder.

Upon customs examination, there may arise a need for further testing and

assessment of container goods before clearance is granted.

Import duties and taxes need to be paid on incoming cargo. The assessment

of same often happens after the cargoes have arrived

The consignee may require some time to arrange for transport of the container

from the ICD.

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

I-6

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

In the case of exports, delays can stem from the following:

Time is needed to process documents.

Some documents may arrive with the container and so require additional time

for processing.

Customs may want to inspect the container and its cargo after it has arrived at

the ICD before releasing it for onward movement.

The multimodal operator will not authorize the loading of the container until the

charges have been paid if they are to be paid by the consignor.

There may be errors and omissions in documents received by customs, the

ships agent or the ICD.

Outbound LCL containers are usually packed over several days, following a

detailed schedule. It is unlikely that the CFS will be able to accommodate all

outbound LCL packing simultaneously.

3. To Assemble Outward Containers for Loading

The third function of storage is to assemble the outgoing containers and to

marshal them into a suitable sequence for loading ahead of the train/barge arrival.

If the outbound containers are all or almost all in the depot before the loading

begins, it provides a window of opportunity for the planners to prepare loading

sequences.

4. To Accommodate Unforeseen Delays

The availability of short term storage, in the case of outward containers, allows

the consignor to send containers to the depot before the expected departure date

and time. In this way, the consignor can be confident that transport to the depot

will not be delayed to the extent that the container misses the train or barge

departure. Conversely, the train or barge arrival may be subject to delay and the

storage function of the yard prevents road vehicles from being tied up in queues

awaiting the late arrival of the incoming transport. In the event of delayed inward

containers, the storage function eliminates the need for road vehicles to remain at

the depot waiting for the containers to arrive.

C.

ICD Handling and Equipment Systems

The performance and efficiency of a container depot depend heavily on its handling

equipment. Indeed, the presence and activity of very large, fast-moving equipment is a

characteristic of the container depot. There are basic types of container handling

equipment and these are discussed below.

1. Lift Truck System

This system may include front-end loaders (top-lift trucks (TLTs) or top loaders,

side-lift trucks (SLTs)) and boom or reach stackers. TLTs and SLTs normally

have a stacking limit of 2-3 containers high (one-deep) while boom or reach

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

I-7

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

stackers, which are more expensive, can stack up to 5-high (one-deep) or 3-4

high (2-3 deep).

Advantages: This technology is relatively inexpensive and easy to maintain as

well as flexible in terms of movement around the ICD. As such, they can achieve

high utilization rates.

Disadvantages: This technology requires relatively high aisle width (15-18 m) to

manoeuver, yields low densities (in the case of TLTs and SLTs), and requires

extremely good soil conditions and paving to bear heavy axle loads.

Figure I-3: Front End Loader

Figure I-4: Reach Stacker

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

I-8

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

2. Terminal Tractor/Trailers/Chassis

This system of moving boxes uses tractors and trailers that can either be of

standard road design or of special design for an ICD, which lacks the lights,

brakes, and heavy suspension required for road trailers.

Advantages: Cheap, easy to handle, doesnt require skilled equipment drivers.

Disadvantages: Tractor-trailers require a lot of space for movement and can only

be used in conjunction with some loading/unloading equipment.

Figure I-5: Tractor-Trailer Set

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

I-9

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

3. Rubber Tyred Gantries (RTGs) or Transtainers

RTGs can normally lift 30.5-40 tonnes under the spreader and have a stacking

capacity of 4-5 high. RTG span widths are anywhere from 2 rows of container

stacking plus 1 trailer lane to 6 rows of storage plus 2 trailer lanes which leads to

high TEU storage density.

Advantages: RTGs yield very high TEU storage density and can typically handle

around 100,000 container moves per year. This technology is very well suited for

high volume operations and requires relatively little land due to the high stacking

densities.

Disadvantages: RTS are relatively expensive, require special paving and

foundations for wheel lanes, have no horizontal transport capability, and require

skilled labour for operations.

Figure I-6: Rubber Tired Gantry (RTG) Crane

4. Rail-Mounted Gantries (RMGs)

Typically, RMGs are used in high volume rail depot operations for rail lo-lo. They

can also be used in container yard operations. RMG span widths vary from one

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

I-10

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

rail track, one trailer lane and 2 rows of container storage up to 6 rail tracks, 4

rows of container storage and 2 trailer lanes.

Advantages: RMGs are considerably faster than RTGs as well as being much

cheaper to maintain. They are also well suited to handle high volumes of traffic.

Disadvantages: RMGs are only useful for lo-lo and CY operations, are not as

flexible as any other system and are the most expensive handling system to buy

in terms of equipment.

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

I-11

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

Figure I-7: Rail Mounted Gantry (RMG) Crane

5. Forklifts

Forklifts are generally only used for stuffing and de-stuffing containers. They are

not generally used in CY operations, but mainly CFS operations. The exception is

heavy duty forklifts which may be used for handling empty containers in the

empties stacks.

Figure I-8: Forklift

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

I-12

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

D.

Factors Influencing Choice of Best System

The selection of the most appropriate ICD container handling system is primarily

dependent on such factors as:

The initial cargo level

The potential for expanding the capacity of the system selected to the ultimate

cargo level

The proportion of cargo to be handled by each mode of transport

(road/rail/IWT)

Limitations of area available (due to physical constraints and/or costs)

Bearing capacity of soil (cost of foundation and pavements)

Constraints on initial capital investment funds available

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

I-13

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

II.

A.

BEST PRACTICES IN CONTAINER YARD OPERATIONS

The ICD Layout and Area Requirements

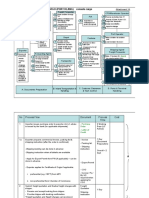

A representation of a generalized ICD is shown in Figure II-1. It provides an overview of

the various areas of the ICD. The orange shaded area represents the depot entrance

and gate activity. This is the main area (not including the interchange area) for the

receipt/delivery operations. The green shaded area represents the CFS operation as

well as customs and other examination areas. Finally, the gray shaded area represents

the container yard operations.

The ICD is an inland depot with open and covered storage areas, and with road, rail,

and/or waterway links with the ports. The physical layout of an ICD depends very much

on the main mode of transport that will access the depot. For instance, a rail depot will

require a gate at the railhead, while an ICD served by an inland waterway will require

barge docking facilities, a truck ICD will need sufficient road access and egress. The

layout also depends to a great extent on the handling system selected.

1. Land Area

The area requirements and land acquisition costs are highly dependent upon the

handling system selected, because of the varying stacking densities and

circulating area (aisle and roadway) requirements of each system. The civil works

costs are dependent upon the area required, and the landfill and pavement

needed to provide the bearing capacities required for each of the different

handling systems.

a) Container Yard

The required area for the container yard must be calculated based on the

various types of cargoes stored in the yard and the size of the boxes used:

export dry cargo, export reefers, import dry cargoes, import reefers, empty

containers. Each of these components will generally have differing space

requirements based on stacking densities and special requirements, i.e.,

reefers. The calculation is based on the following formulae:1

TEU _ spaces _ required =

(TEU _ throughput ) x( peak _ ratio ) x(days _ dwell _ time)

365

area _ required = (TEU _ spaces _ required ) x ( square _ metres _ per _ TEU _ space )

where the TEU_spaces_required represents the total number of TEUs needed

for storage. This is not the same as the number of twenty foot ground slots

which represent the number of designated storage areas on the container yard

surface, not including any stacked container positions. Dwell time in this

1

All land area formula taken from ESCAP/UNDP Transport Financial/Economic Planning Model,

Volume 3: Inland Container Depots Module, User Manual, UN, 1992.

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

II-1

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

calculation is average dwell time or the average time (in days) that a container

is stored in the container yard.

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

II-2

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

Figure II-1: ICD Layout

Rail sidings

Security Fence

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Loaded Container

Gate

Train Handling Area

Gate

Storage Area

CFS Shed

Interchange

Area

Empty Container

Storage Area

Interchange

Area

CFS Transit Shed

Customs/

Health

Exam Shed

Gate

Specialized

Containers

Admin. Building

& Control Centre

Vehicle

Holding Area

Container

Repair Area

Workshop

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

II-3

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

b) CFS

The area for the CFS consists of the CFS shed itself and the CFS truck apron

used for containers and trucks and the area is calculated separately for export

and import cargoes as the dwell times are normally higher for import cargoes.

The general method for calculating the area is based on calculating the area

for storage in the shed, the length and depth requirements of the CFS, the

handling and customs area width, the truck apron required, and any additional

service space based on method of transport (rail, road, IWT), outdoor storage

space, etc. The shed area is calculated as:2

Shed _ area =

where:

(a) =

(b) =

(c) =

(d) =

(TEUs _ per _ annum) x(a ) x(b) x(c) x(d )

Number _ of _ working _ days _ per _ annum

area of floor space occupied by an average container load of cargo

amount of space required for a fork-lift truck to manoeuvre

peak load factor

average dwell time of cargo

c) Packing/Stripping Dock

A packing/stripping dock can be used for those shipments that come in FCL

lot-sizes through the ICD for stuffing and de-stuffing due to inadequate

facilities or provisions for customs clearance at the origin/destination. This

cargo does not need to be handled through a CFS since no CFS storage

function is required. The calculation for the span of the packing dock is

Packing _ Dock _ Area =

( packing _ dock _ length _ required ) x(cov ered _ dock _ area _ width )

d) Overtime Cargo Warehouse

The use of the overtime cargo warehouse is for those breakbulk consignments

that remain at the CFS for extended periods of time (e.g. more than 20 days).

The rationale for this warehouse is to remove the cargo from the CFS in order

that it does not interfere with CFS efficiency. This situation usually arises with

import cargo that may have problems with import documentation. Calculation

of overtime warehouse area is:

Overtime _ warehouse _ area =

(daily _ peak _ CFS _ import _ c arg o) x(% _ overtime) x(overtime _ dwell _ time)

( storage _ density _ in _ tonnes / m 2 ) x(useable _ storage _ area _ as _ % _ of _ total )

e) Container Repair Facility

This facility is for use in minor repairs of containers. This area is not for major

repairs, which will be done off-site.

Taken from Handbook on the Management and Operation of Dry Ports, UNCTAD, 1991.

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

II-4

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

f)

Railway Siding and Truck Access

Space for railway tracks and siding requirements are very dependent on the

unique characteristics of each project. Factors that need to be considered

are: area and alignment needs for the extension of the rail tracks to the

ultimate stage of ICD expansion; the number of loading and unloading tracks;

engine escape tracks; receiving and departure tracks; storage tracks; and type

of rail-side container handling area that is appropriate for the container

handling system selected. Truck access, again, is dependent on the volume

of traffic expected to be handled by the facility. Adequate access and egress

from the facility through adequate gate capacity so as to make sure that undue

delays are not experienced at the gates.

2. Total Area Requirements Inside the ICD

All the facilities described above are necessary for calculating the area required

within an ICD. In addition to these requirements are:

a) Additional covered area to provide for:

Offices (including administration, operations, customs);

Maintenance workshop;

Canteen;

Gatehouse, etc.

b) Additional paved area for provide for:

Internal roads and boundaries;

Truck, car, tractors and trailer parking;

Maintenance yard;

Broken space, etc.

3. Total Area Requirements Outside the ICD

In addition to the operational areas inside the ICD, substantial additional land

acquisition and civil works costs are typically incurred for access to the ICD and

for supporting infrastructure. Areas required for rail spur to the ICD, access and

perimeter roads, and areas for supporting infrastructures (i.e., water filtration,

sewage treatment) are some possible extra needs.

B.

Container Yard Layout

The container storage function is important in depot operations and can require a

significant amount of land area. The number of containers that can be stored in the yard

depends directly on the handling equipment used for movement and stacking. Roughly,

for every 1000 TEUs in storage, the container yard requires areas of about 12,000 m2 for

a yard gantry system, or over 50,000 m2 for a chassis system.

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

II-5

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

The detailed design and layout of the container depot will vary according to the site

features and to the stacking and transfer systems adopted, however, there are some

general features that are common to all systems.

1. General Storage Area

One of the striking features of the general storage area is that containers are not

stacked haphazardly throughout the yard. Instead, they are arranged in defined,

rectangular groups called blocks. The blocks are separated by a) roadways

which are the main access routes between the yard, interchange areas, CFS, etc.

and are usually 25-30 m wide, and b) aisleways which provide access to and

passing between the blocks and are usually 15-20 m wide.3 Each block holds

many hundreds of containers and within each block, the containers are arranged

in an end-to-end alignment along the length of the block or row and also in a

side-to-side arrangement or line. The block is defined by painted lines on the

yard surface. The basic unit within the block is known as the twenty-foot ground

slot (TGS), which is identified as a painted outline of a twenty-foot container.

Practically, each row normally contains an even number of TGSs. In this way, the

row can accommodate either twenty foot boxes or forty foot boxes.

Most containers passing through the depot are considered to be general purpose

boxes which carry a mix of dry general cargoes. These containers are stored in

the main storage blocks. The main blocks are divided into two areas outward

(export) blocks and inward (import blocks). Efficient operations places the

outward blocks closest to railhead/inland waterway berth and places the inward

blocks closest to the gate and interchange areas. This serves to reduce the

distance and time required for transfer of the container at the time of onward

movement.

2. Special Containers and Purposes

In addition to general storage described above, the depot will most likely handle a

range of containers, which require special facilities. As such, distinct areas of the

container yard are set aside for handling these special containers. There can be

up to seven different special areas present in a typical container yard.

A reefer area (for refrigerated containers)

A dangerous goods area

An out-of-gauge area

A high-value area

An empties area

A customs and port health examination areas

An examination area for damaged containers.4

a) The reefer area is required to accommodate refrigerated containers carrying

cargoes that need to be kept below ambient temperature. The dedicated area

provides power supply outlets or connections to a supply of coolant gas. This

3

4

PDP, ILO, 1999.

PDP, ILO, 1999.

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

II-6

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

area usually consists of one or two lines of side-by-side slots and can

sometimes accommodate stacking to two high. Apart from the power/gas

supply, the main feature of the area is a route of safe access by depot or

multimodal transport operators (shipping line, freight forwarder, transport

operator) staff to check the container temperatures regularly and to service or

repair the refrigeration units. The area is usually located to one side of the

general storage area. Handling equipment is kept away from the area unless

instruction is given for movement of containers. In addition, the area should

provide a fenced-off pedestrian walkway that allows staff to enter and leave

the area without passing through a vehicle route.

b) Containers carrying dangerous cargoes must be segregated from the rest of

the containers in storage. This precaution arises from the need to protect

other containers from such things as contamination, fire, corrosion, etc. In

addition, segregating containers with dangerous cargoes in a specified

location and not allowing stacking, i.e., only one high, provides fast and easy

access should it be required. It is possible that certain containers carrying

dangerous cargoes also need to be segregated from each other. These

requirements and necessary handling actions are outlined in the IMDG Code,

which provides a listing of dangerous goods, which are categorized by the

type of hazard they pose. The Code is published and regularly updated by the

International Maritime Organization (IMO).

c) The out of gauge area accommodates non-standard containers including

platforms and flats carrying over-height, over-width, over-length cargoes.

These cargoes cannot typically be stacked and so are usually stored directly

on the yard surface. This area also accommodates oversize containers

those 48 foot long or 53 foot long boxes as well as uncontainerized cargoes.

This area is commonly located near the depot gate or interchange area to

facilitate access.

d) Terminals customarily allocate a particular area of the yard for cargoes

classified as high-value. Special facilities are not usually required, but

practically, the area is highly visible at all times and can be monitored closely

by both control room staff and depot security staff.

e) In addition to storing containers full of cargo, a depot usually also provides

storage space for empty containers. There are two classifications of empty

containers. The first group includes those empty containers that are passing

through the ICD towards a specific destination. The second group of empty

containers includes those containers that are being returned to the container

yard from a consignee or CFS and are to be recirculated to shippers at some

unspecified future date. Typically, when an empty box is needed, any box

belonging to the correct owner will do, i.e., they are not requested by specific

container number, but rather by the size and type. Because of this, empty

containers can be stacked higher than loaded containers and are often

stacked closely together, many tiers high. This process is known as blockstacking.

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

II-7

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

f)

Another area that is provided in the container yard is an examination area for

customs and health officials. Customs examination is needed to check the

accuracy of the shipping documents, to take samples for analysis, to ensure

that illegal goods are not being moved, and to calculate import duties and

taxes. Health officials will want to inspect foodstuffs, plant materials and

animals to ensure that they are healthy, fit for consumption or for transport. It

is not practical or secure to undertake contents examination in the container

yard and so, customs has its own assigned area of the ICD, which consists of

an open area for inspection as well as secure bonded area for storage of

valuable cargoes. Likewise, the health area will have its own designated

examination area which may also contain a laboratory for analyzing samples

and possible a cold store for temperature sensitive goods. The existing

practice for customs is for selective examination based on set criteria as

opposed to full and total inspection of every container. This selectivity means

that the space allocated for customs is generally less than would be required

for the examination of all containers.

g) Finally, depots may have an area designated for the examination, storage and

repair of damaged containers. It may not be safe to store damaged

containers with regular containers.

C.

Container Handling Methods

There are various types of handling systems. Some systems use only one type of

equipment for all stacking/unstacking and transfer operations. Examples of these

systems are the tractor-trailer system and the lift truck system. Other systems, such as

the RTG system and the RMG system require more than one equipment type to handle

both stacking/unstacking and transfer functions.

Each handling system has unique defining characteristics with respect to a) the layout of

the container yard and b) the operational process of handling containers. These are

described below for each of the handling systems listed above (see Section I E for

equipment illustrations).

1. Tractor-Trailer System

Tractor-trailer units are seldom used alone in an ICD. Typically, they are used to

complement other container handling equipment systems such as RTGs and

RMGs. They tend to be used if the distance between the railhead/berth and the

container yard is large since they are a fast method of container transfer.

a) The typical feature of a container yard using a tractor-trailer system is that the

storage blocks are very long and narrow. Between each block is an aisleway

and there is typically a perimeter roadway that runs completely around the

container yard. In the container yard design, there is a tradeoff involving the

length of the block and roadway access the shorter the block, the easier and

quicker the access, however since the tractor-trailer system is relatively quick,

the length of the blocks tend to be longer than for other handling systems.

The longer blocks tend to be more storage efficient as there is less area taken

up in lanes for vehicle access.

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

II-8

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

b) Operationally, the tractor-trailer yard system is used in conjunction with lifting

equipment such as RTGs and RMGs. The tractor-trailer sets handle the

transfer of the containers to/from the storage area to the

railhead/berth/interchange areas. For inward containers, the boxes are landed

onto the trailer by lifting equipment (cranes, dedicated lift trucks, etc.) and are

then delivered to the assigned storage slots. For the discharge of containers

from the ICD, boxes are lifted from the storage block and placed on the trailer.

The tractor then transfers the container to an interchange where it is

transferred to a road vehicle for delivery. The process is reversed for outward

boxes.

2. Lift Truck System

a) In a lift truck system (front-end loaders or reach stackers) the container yard

layout includes narrow blocks consisting of between 2 and six rows of

containers (see Figure II-2). Within each block, the ground slots measure

6.6m long by 2.6m wide. The aisleways are relatively larger to accommodate

the manoeuvring and stacking requirements of the lift trucks aisleway

requirements are between 11m and 18m and roadway requirements are

between 25m and 30m. Thus, this system has relatively poor space utilization

in terms of the ratio between stacking and non-stacking spaces. The depth of

the storage block, i.e., the number of rows it has, is determined by the type of

lift truck equipment chosen. The relevant characteristics include lifting

capacity and reaching capacity. For instance, front-end loaders are restricted

to stacking/unstacking one deep thereby limiting the block width to two slots

with aisleways on each side. Reach stackers, however, can stack/unstack

three deep, thereby allowing the blocks to be six slots wide with an aisleway

on each side. The length of the blocks tend to shorter in the lift truck system

since lift trucks are slow and so a shorter block decrease the distances

travelled.

Containers can be stacked on top of each other in a lift truck system, but the

stacking capacity is limited by two things: the tradeoff between high stacks

and accessibility of bottom containers, as well as the diminished lifting

capacity of lift trucks at higher stacking tiers.

b) Operationally, many ICDs use lift trucks as back-up equipment to handle

empty containers into and out of storage in an empties area. They can be the

principal handling system in general storage areas either in a direct or relay

operation. In a direct operation, the lift truck transfers containers between the

railhead/berth and the yard and also stacks/unstacks within the yard. Lift

trucks are effective at transferring containers from stacks to road transport at

interchanges.

In a relay operation, tractor-trailers are used for movement into and out of the

general storage area while lift trucks are used only for stacking and unstacking

in the blocks and at interchanges.

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

II-9

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

Lift trucks are considered to be versatile handling machinery for a variety of

reasons. They can be fitted with a range of attachments, including

attachments to handle uncontainerized cargo. Mechanically, they are easy to

maintain and as a result, are popular for operations in ICDs with relatively

small volumes of containers and/or a variety of cargo types.

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

II-10

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

Figure II-2: Lift Truck Container Yard Layout

Rail sidings

Security Fence

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Loaded Container

Gate

Train Handling Area

CFS Shed

TGS is

6.6m x 2.6m

Gate

Storage Area

Aisleway

11-18m

Roadway

25-30m

Empty Container

Storage Area

Interchange

Area

CFS Transit Shed

Customs/

Health

Exam Shed

Gate

Specialized

Containers

Admin. Building &

Control Centre

Vehicle

Holding Area

Container

Repair Area

Workshop

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

II-11

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

3. Rubber Tired Gantry Crane System

In this system, the transfer of containers from the railhead/berth is carried out by

tractor-trailer units, while the RTGs are constrained to working in the container

yard.

a) The container yard layout in the RTG system exhibits a more dense stacking

capacity than the lift truck layout (see Figure II-3). Blocks are made up of six

rows of containers with an additional truck lane roughly 4.8m wide, for tractortrailer sets to drive in to deliver and collect boxes from the cranes. Each

ground slot measures 6.4m long by 2.9m wide, which is smaller than for the lift

truck system. The truck lane takes the place of an interchange area. The

yard surface alongside each block is often specially strengthened to form a

wheel track for the RTG. Individual blocks may be separated by aisleways (up

to 4m wide) or only a narrow space (1.5 to 2m wide), depending on whether

tractor units need access to the blocks. Roadways are located between the

inward blocks from the outward blocks as well at the end of the storage blocks

25 to 30m wide. The roadways at the end of the storage blocks serve two

purposes the first is to provide block access to transfer and road vehicles,

and the second is to provide a means for the RTGs to move between storage

blocks.

Container stacking in an RTG system depends on the RTG size they

typically stack one-over-three but can go as high as one-over-six and

operational considerations as discussed above. Typically, outward stacks are

3 to 4 containers high and inward stacks are constrained to 2 to 3 containers

high to reduce the amount of shifting needed to access the boxes on demand

by the consignee.

b) As mentioned, RTGs are restricted to operating in the container yard. Tractortrailer sets are used to collect containers from and deliver containers to the

container stacks. In the receipt/delivery operations, road vehicles can either

deliver and collect the containers in the truck lane interchanges within the

blocks, or they can transfer the containers to yard tractor-trailer sets at an

interchange area located near the gate.

RTG systems are very space efficient because of their high stacking ability

and the compactness of the storage blocks. They are also operationally

effective systems as they take advantage of the speed, manoeuvrability and

reliability of the tractor-trailer system and the lifting and stacking efficiency of

the RTGs. The system is also reasonable flexible since the RTGs can move

between blocks.5

PDP, ILO, 1999.

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

II-12

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

Figure II-3: RTG Container Yard Layout

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

II-13

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

Rail sidings

Security Fence

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Loaded Container

Gate

Train Handling Area

CFS Shed

TGS is

6.4m x 2.9m

Truck Lane

4.8m

Aisleway

1.5-4m

Roadway

Empty Container 25-30m

Gate

Storage Area

Storage Area

CFS Transit Shed

Customs/

Health

Exam Shed

Specialized

Containers

Gate

Admin. Building &

Control Centre

Vehicle

Holding Area

Container

Repair Area

Workshop

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

II-14

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

4.. Rail Mounted Gantry Crane System

In this system, the transfer of containers from the railhead/berth is carried out by

tractor-trailer units, while the RMGs are restricted to working in the container yard,

moving along their pairs of rails.

a) The container yard layout in the RMG system illustrates the densest container

storage layout of the different equipment handling systems (see Figure II-4).

Typically, each crane spans 14 rows of containers between the rails, although

cranes spanning up to 24 rows are available. The ground slots are generally

6.4m long by 2.9m wide. The gantry has a cantilevered extension to one end

of the span, with an outreach of five metres. It overhangs a truck lane of

about 4.8m wide along which tractor-trailer sets drive to deliver containers to

or collect boxes from the crane. As in the RTG system, the truck lane acts as

the yards interchange area. The yard surface on which the rails are mounted

is specially strengthened and sometimes raised to take the entire load of the

RMG.

In this system, there is no need for rows to be interrupted by roadways and so

each block can extend for the entire width of the yard. The blocks are

separated by a roadway between 25m and 30m wide and a perimeter road

runs all the way around the yard. The cranes move across the roadways

between the blocks along rails that are sunk into the yard surface.

RMGs typically stack one-over-four and stacking height combines operational

considerations with the capacity of the RMG. As in the case of the RTG

system, outward containers are generally stacked between 3 and 4 high, while

inward containers are stacked 2 and 3 high. Empties can be stored at the end

of the blocks to further take advantage of the cranes high stacking ability.

b) RMGs operate exclusively in the container yard transferring boxes to and

from the stacks as well as shifting boxes in the stacks themselves. Tractortrailer sets are used to collect containers from and deliver containers to the

container stacks. In the receipt/delivery operations, road vehicles can either

deliver and collect the containers in the truck lane interchanges within the

blocks, or they can transfer the containers to yard tractor-trailer sets at an

interchange area located near the gate.

RMG systems are very space efficient because of their high stacking ability

and the compactness of the storage blocks. They are also operationally

effective systems as they take advantage of the speed, manoeuvrability and

reliability of the chassis system and the lifting and stacking efficiency of the

RMGs. Stacking and unstacking operations can be extremely rapid in this

system, especially if there are multiple RMGs operating in one block.

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

II-15

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

Figure II-4: RMG Container Yard Layout

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

II-16

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

Rail sidings

Security Fence

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Gate

Gate

Train Handling Area

CFS Shed

TGS is

6.4m x 2.9m

Empty Container

Storage Area

CFS Transit Shed

Loaded Container

Storage Area

Truck Lane 4.8m

Roadway 25-30m

Customs/

Health

Exam Shed

Gate

Admin. Building &

Control Centre

Vehicle

Holding Area

Specialized

Containers

Container

Repair Area

Workshop

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

II-17

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

D.

Yard Address System

Given the nature of the service provided by an ICD and the volume of containers

entering and leaving the depot during any given period, a crucial element in ICD

operation is the placement, location specification, and the recording of container

assignment. To this end, a systematic numbering or locational classification scheme

must be implemented. This facilitates planning and operation of the yard through

container tracking via container yard location. The system for numbering each storage

location is known as the yard address system. Each numbered slot provides a unique

yard locator code or identification the yard address. Assigning and updating the yard

address of each container provides the means for the ICD to control the movement of

each container including the transfer between external transport mode, storage,

inspection, CFS, etc. For the yard address system to work, it is imperative that all

personnel working in an operational has a working knowledge of the system. This

ensures that:

Containers being received into the ICD are placed in that part of the container

yard assigned to them.

The correct yard address for each of those storage positions is communicated

to the control room as soon as the container is in position, and whenever a

container is moved within the ICD.

The correct container is moved whenever an instruction is issued to take it to

the interchange, CFS, examination area, or to another depot location.

A particular container can be located quickly and without error whenever the

control room makes such a request.

A register can be maintained, showing at any moment exactly which slots are

occupied and which are available for incoming containers.6

The container yard and yard address system is set up as a three dimensional grid,

identified by a set of coordinates. These coordinates typically have four components.

i) A block identification; e.g., A, B, C, etc.

ii) A row classification, usually consisting of a two or three digit number

representing the row within the block, e.g., 01, 02, 03, etc.

iii) A line reference, usually a two digit number identifying the line within the row.

The line number frequently starts at 01 at one end of each block.

iv) Where containers are stacked more than one high, the final classification

component is a single digit or letter representing the tier or layer within the

stack. Generally, numbering starts at ground level with the number 1 or letter

A.

The basic unit for the yard address system is the twenty-foot slot. As such, the yard

address system must have some mechanism for assigning and recording locations for

forty-foot containers. Logically, each forty-foot container occupies two twenty-foot

storage slots. Designating yard locators for forty-foot boxes can be handled in a number

of ways including recording the numbers of the two slots occupied; assigning the forty

foot container just the even number of the pair occupied by it, or adapting the numbering

system used to indicate twenty foot and forty foot bays in a container ship the twenty

6

PDP, ILO, 1999.

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

II-18

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

foot slots are numbered consecutively 01, 03, 05, 07, etc. while the forty foot containers

are given even numbered slots (forty foot container occupying 01 and 03 would be

numbered 02).

As is evident, there are a number of ways that address systems can be structured. The

crucial point is that everyone using the system fully understands it.

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

II-19

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

Figure II-53: Yard Address System

Source: Portworker Development Programme, ILO, 1995.

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

II-20

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

E.

Storage Planning and Control Procedures

The container yard is one of the areas of the ICD where much physical movement

occurs container shuffles; container movements to/from interchanges, CFS,

examination sheds, repair facilities, etc. Thus, the planning, control and supervision of

the container yard activities are challenging. The shear volume and variability of the

activities that occur in the ICD requires that the activities must be planned in detail and

personnel must follow the plans precisely and efficiently for both productivity and safety

reasons. The two broad categories for storage planning and control procedures are: the

allocation of storage locations and the determination of storage space requirements.

1. The Allocation of Storage Locations

The assignment of containers to specific storage locations is a critical element in

the efficient and safe operation of the container yard. It is good practice to group

containers that meet certain conditions together, i.e., dangerous goods containers

should be segregated from the general storage area for safety of caroges,

outward containers should be kept separate from inward containers for ease of

tracking and access, high-value containers should be stored in highly visible

areas for security reasons, etc. This leads to the layout of the general storage

areas and special areas described above in Section II-B. Within these designated

areas, a series of more specific stacking principles are applied. In fact, the inward

and outward blocks are divided into zones and sections of zones. One purpose of

the zoning exercise is to simplify and reduce the time and cost of container

handling, primarily in the receipt/delivery process. Examples of zoning principles

in the case of inward containers are:

Containers are generally grouped together according to the transport operator

that is handling them on that journey.

Containers destined to the same consignee or importer are grouped together

Containers destined to landlocked countries are often grouped according to

the country of destination.

In addition to these general zoning principles, further segregation of containers is

used, often according to container dimension and status. A similar exercise is

applied to outward containers. There are also separate rules for stacking and

storing empty containers.

2. The Determination of Storage Space Requirements

Once the different zones and section are delineated, the storage planner must

decide how much space to allocated each section. The ground area

requirements for each category of containers depends on three factors

The expected number of containers for each category type

The stacking height of the containers in each category

The average dwell time (time spent in storage) of each category of containers

The document process ensures that planners know, ahead of time, how many

containers and of what type will be arriving from inland transport (i.e.,

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

II-21

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

train/barge/road) and how many will be discharged for loading. Multimodal

transport operators provide all the necessary data in advance of the

train/barge/road arrival.

As to the second factor, most container storage involves the stacking of

containers more than one high. There is a trade-off between stacking additional

levels and gaining access to containers at the bottom of the stack. The higher the

stack, the more moves required to get at the bottom container. For example, the

bottom container in a stack of five requires nine equipment moves to be released

from the stack.

In general, inward containers are generally stacked to lower heights (2 to 3 high)

than outward containers (3 to 4 high) as it is more difficult to predict when boxes

will be claimed, while outward containers are sequenced to be loaded at the same

time on departing linehaul transport. Also, empty containers are usually

requested by type and owner as opposed to specific container ID and as such,

can be stacked relatively high (5 or more depending on the stacking equipment

used). Stacking restrictions are applied to special containers such as reefers

(only one or two high), containers carrying dangerous goods (only one or two

high), out-of-gauge containers (often only one high), and non-ISO length

containers.

With respect to dwell time, there is always a minimum dwell time associated with

each container since there are documentary and operational procedures to be

completed with each arrival and departure. However, every effort is taken to keep

dwell times to a minimum because the longer the dwell time:

a) The more space is required to accommodate the containers.

b) The higher and denser the stacks have to be to accommodate the volume of

containers, leading to more shifts for container retrieval.

c) The likelihood of congestion in the yard.

d) The possibility of delay for goods in transit with the potential of deterioration of

goods and an increase in the cost of capital for shippers and receivers.

ICDs have policies in place to encourage lower dwell times. For outward

containers, ICDs will have a specified acceptance period, say up to 6 or 7 days

before the arrival of linehaul transport (train/barge) and a closing date before

departure. For inward containers, ICDs specify a free storage period after which

charges are levied on a daily basis.

F.

Information System Applications

Planning and control functions cannot be effectively undertaken without the presence of

an information system that provides comprehensive and up-to-date information. The

control function requires knowledge of:

The number of expected containers

The identity of the expected containers

The location of each container within the ICD at any given moment

The stage that has been reached in each containers handling sequence

Intermodal Transport Services to the Interior Project

II-22

Advisory Services to Intermodal Transport Service Providers

The current availability of yard space and its individual zones and sections.

In terms of container yard operations, the information systems must provide the following

components the container records and the yard inventory. The most effective system

will have each component cross-linked with the other for ease of use, analysis and rapid

information retrieval. The container records provide important information for container

yard operations, especially container tracking (see Figure II-6). The required information

is the container ID and the yard slot address, which must be updated any time the

container is handled. The function of the container record is largely one of control. In

comparison, the yard inventory is a planning tool, as it serves to help planners direct

containers to appropriate locations throughout the yard.

There are various configurations of information systems from a completely paper-based

system to a fully computerized system. For example, Figure II-7 illustrates how the

inventory consists of a set of plans. The plans can be paper based or computerized.

Obviously, the paper systems are more cumbersome, inefficient, error-prone and less

useful for planning purposes as timely information is not immediately available.

At the other end of the spectrum, an online computerized ICD MIS yield benefits to

supervisory preparatory activities. These benefits include:

The reduction of paperwork since data is only entered once and then is

automatically accessible in all the required forms (container records, yard

inventory and various summary lists).

Instant availability and accessibility of information at all relevant desks.

Timeliness and ease of data updates (to indicate container arrival, stacking,

movement within the depot, examination, clearance and departure).

The ease of cross-checking data entry.

The reduction of time taken for documentation procedures.

Automatic data analysis, reorganization and presentation for various parties.

The provision of checks to ensure that all required data is available and

prompts to staff if data is insufficient.

Automation of customer billing based on movement and activity records

associated with each container.7

The use of electronic data interchange (EDI) also confers various benefits onto users as