Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Tmp8a69 TMP

Transféré par

FrontiersDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Tmp8a69 TMP

Transféré par

FrontiersDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

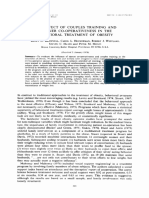

Health Psychology Research 2013; volume 1:e24

Abstract

co

m

This study examined the effect of anti-fat

attitude counter-conditioning using positive

images of obese individuals participants completed implicit and explicit measures of attitudes towards fatness on three occasions: no

intervention; following exposure to positive

images of obese members of the general public; and to images of obese celebrities.

Contrary to expectations, positive images of

obese individuals did not result in more positive attitudes towards fatness as expected and,

in some cases, indices of these attitudes worsened. Results suggest that attitudes towards

obesity and fatness may be somewhat robust

and resistant to change, possibly suggesting a

central and not peripheral processing route for

their formation.

on

-

Introduction

To date there have been limited efforts to

reduce implicit or explicit anti-fat attitudes

and these have demonstrated varying effectiveness.1,2 Interventions aimed at reducing

anti-fat attitudes include modifying existing

knowledge and beliefs about the causes and

controllability of overweight and obesity,3,4 or

evoking empathy for these individuals.5 A

number of studies have reported no change in

attitude or modest positive effects.6,7 Others

have produced more promising results, for

example, participants receiving information

about the uncontrollable causes of obesity

reported reduced anti-fat attitudes whereas

those receiving information that obesity is

caused by controllable factors demonstrated an

increase in anti-fat attitudes.8 Although interventions to modify anti-fat attitudes have had

limited effectiveness, greater success has

been observed with attitudes towards other

individuals and groups. For instance based on

the premise that we associate positive attrib[page 122]

Key words: counter-conditioning,

strength, obesity.

attitude

Contributions: the authors contributed equally.

Conflict of interests: the authors report no conflict of interests.

Received for publication: 21 December 2012.

Accepted for publication: 14 January 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution NonCommercial 3.0 License (CC BYNC 3.0).

Copyright S.W. Flint et al., 2013

Licensee PAGEPress, Italy

Health Psychology Research 2013; 1:e24

doi:10.4082/hpr.2013.e24

of Sport and Physical Activity,

Health and Wellbeing Research Institute,

Sheffield Hallam University; 2Department

of Sport and Exercise Science,

Aberystwyth University; 3School of

Sport, University of Stirling, United

Kingdom

on

l

1Academy

Correspondence: Stuart Flint, Collegiate Hall,

Collegiate Crescent Campus, Sheffield Hallam

University, Sheffield, S10 2BP, United Kingdom.

Tel. +44.0114.225.5582 - Fax: +44.0114.225.4377

E-mail: s.flint@shu.ac.uk.

er

ci

al

us

e

Stuart W. Flint,1 Joanne Hudson,2

David Lavallee3

utes with accomplished, famous individuals,

counter-conditioning involving exposure to

well known black individuals (i.e., famous

black athletes, politicians, actors) has been

used to modify racial attitudes.9 Compared

with exposure to non-racial or pro-white

images participants initial white preference

reduced. Importantly, this effect was observed

for implicit but not explicit attitudes.

A plethora of research has examined attitude change in relation to media and advertising stimuli and the role of persuasion in shaping existing attitudes and has been more successful.10,11 A common framework for this

research, the Elaboration Likelihood Model of

persuasion and attitude formation,12 proposes

two routes to explain attitude change. Central

route processing involves repeated exposure

and direct attention to relevant stimuli producing robust attitudes. In contrast, peripheral

route processing is less complex, whereby attitudes are shaped by superficial aspects of a

message (e.g., source credibility) resulting in

weaker, more malleable attitudes.12

Consequently, less cognitive effort is required

to change attitudes formed via this route.

These two routes by which attitudes are

formed may therefore account for the difference in effectiveness of attitude interventions.

Two studies have examined the effectiveness of an intervention comprised of counterconditioning and evoking empathy to reduce

anti-fat attitudes. The first employed a variety

of conditions as part of the intervention: a

video of an obese female discussing her experiences of discrimination, written facts related

to the relationship between the environment

and genetics and obesity and role-play where

an obese persons perspective was taken by the

participant.13 Weise and colleagues reported

that beliefs about the controllability of obesity

reduced but it was unclear whether counterconditioning or evoking empathy was responsible for this change. However, a recent review

of anti-fat intervention studies has questioned

these findings,1 on the basis that initial

between group differences at baseline were

not accounted for.

In the second of these studies6 participants

were exposed to four 10 minute videos (evoking empathy, control video, counter stereotypical portrayal, stereotypical portrayal). These

interventions induced little change in both

implicit and explicit attitudes. Indeed a counterintuitive trend was identified by Gapinski

and colleagues, where explicit anti-fat attitudes reduced after exposure to the stereotypical portrayal. These findings may have been

the result of overexposure to anti-fat portrayals

which consequently may have been condemned by participants leading to lower explicit anti-fat attitudes. As a result of the limitations of the above studies, the effectiveness of

counter-conditioning as an anti-fat attitude

Counter-conditioning

as an intervention to modify

anti-fat attitudes

[Health Psychology Research 2013; 1:e24]

intervention is still unclear and requires further examination. Future research should

attend to the limitations of both these studies

when examining anti-fat attitude interventions. First, interventions should be examined

separately to ensure that different interventions can be clearly delineated unlike in Weise

et al.13 Second, attitude formation is vulnerable to social desirability influences therefore

an individuals attitude is often similar to

those of others around them.14 Thus, a major

limitation of Gapinski et al.6 is that participants were exposed to the video conditions and

completed study measures in small groups

which may have had an effect on participants

responses, leading to a non-significant effect.

Thus negative images of obese individuals

can heighten anti-fat attitudes but whether

positive images can decrease these attitudes is

unknown. The aim of the present study was to

examine the effect of a counter-conditioning

intervention using positive images of obese

members of the general public and celebrities

on anti-fat attitudes. Based on extant

research9 it was hypothesized that both sets of

images would result in reductions in anti-fat

attitudes, with a greater effect of celebrity

images.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Twenty eight volunteer participants (17

men, 11 women; aged 18-35 years, mean age =

22.43, SD3.59 years) were recruited.

Article

Procedures

er

ci

al

us

e

Using a within-subjects design (i.e., participants acted as their own controls), participants

attended the laboratory on three separate occasions on different days. In the initial baseline

condition participants completed all measures

and received no manipulation. In the two

experimental conditions participants were

either exposed to a slideshow of overweight

and obese members of the general public or

celebrities (11 male and 11 female; 81% white

for both conditions), presented in counter-balanced order. All images were non-stereotypical; for example, images of doctors and fitness

instructors in the general public condition, and

in the celebrity condition the image was

accompanied by information detailing the

individuals achievements. This information

was included to reinforce positive associations

with the celebrities, as it has been suggested

that this association impacted the reduction of

negative racial attitudes.9 Thirty images were

sampled from the internet and three independent researchers examined the images to

ensure they did not promote the stereotypes

associated with overweight and obese, as

measured in the F-scale.17 After the intervention participants completed the measures

described above.

Results from a pilot study (n=5) indicated

that scores on the BAOP,15 AFAS16 and F-Scale17

became more positive in response to these

stimuli. Verbal feedback suggested that individuals in the public images were perceived as

positive and non-stereotypical, whilst celebrity

images were recognised as portraying

admirable individuals.

on

-

co

m

Participants reported their age, sex, exercise frequency and perceptions of the words fat

(Q1: How insulting do you believe the word fat

is?) and obese (Q2: How insulting do you

believe the word obese is?). Their height and

weight were measured by the first author to

calculate their Body Mass Index (BMI) using

the following equation: BMI = weight

(kg)/height (m2). To respond to Q1 and Q2 participants used a response scale of 0-10 which

was anchored by 0 = not at all and 10 =

extremely insulting. Participants also completed online versions of the Attitudes Towards

Obese Persons and Beliefs About Obese

Persons scales (ATOP, BAOP)15 that measure

positive and negative attitudes towards obese

people and perceived controllability of obesity,

respectively. The ATOP has 20 items with

scores ranging from 0-120 where low scores

represent more negative attitudes and the

BAOP has 8 items with scores ranging from 048 where low scores represent a stronger belief

that obesity is controllable. Participants also

completed the Anti-Fat Attitudes Scale

(AFAS)16 that includes 5 items measuring the

magnitude of anti-fat attitudes, where scores

range from 0-25 (higher scores represent

stronger anti-fat attitudes), the F-Scale

(Shortened version of the Fat Phobia scale)17

with 14 items measuring the degree to which

individuals associate stereotypical characteristics with being fat (responses range from 0-5

where higher scores are indicative of a perception that the characteristics are associated

with being fat).

The final computer-based measure was a

version of the Implicit Association Test (IAT)18

designed to measure implicit attitudes towards

fatness and thinness, using stimuli words

employed previously.19 The measure provides

an indication of the individuals implicit preference for fatness or thinness as opposed to a

direct measure of absolute attitudes.

Participants are presented with weight related

words and associate these as quickly as possible with one of two pairings: fat/pleasant and

thin/unpleasant or fat/unpleasant and

thin/pleasant. The seven step procedure outlined in prior work was employed,20 where participants were required to respond to each of

the pairings once familiarised with the test:

(1) pleasant or unpleasant; (2) fat or thin; (3)

fat/pleasant or thin/unpleasant; (4) fat/pleasant or thin/unpleasant; (5) thin or fat (6)

fat/unpleasant or thin/pleasant; (7)

fat/unpleasant or thin/pleasant. Only steps 3, 4,

6 and 7 are used to measure respondents

implicit attitudes (see below); the remaining

steps are practice stimuli to engage participants with the process. Participants are pre-

on

l

Measures

total response latency for the pairings

fat/pleasant and thin/unpleasant versus

fat/unpleasant and thin/pleasant to represent

implicit attitudes: (1) delete responses greater

than 10,000 m/sec (2) delete participants data

where more than 10% of responses have a

response latency less than 300 msec (3) compute the inclusive standard deviation for all

responses in steps 3 and 6 and similarly in 4

and 7 (4) compute the mean latency for

responses in steps 3, 4, 6 and 7 (5) compute

the main differences (mean step 6 - mean step

3 and mean step 7 - mean step 4) (6) divide

each difference score by its associated inclusive standard deviation and (7) calculate the D

score as the equal weight mean of the two

resulting ratios. Positive scores are indicative

of anti-fat attitudes.

Repeated measures one-way ANOVAs with

Bonferroni correction for confidence interval

adjustment and follow up post-hoc tests with

Scheff correction were used to compare attitudes between conditions. Paired t-tests were

conducted to locate between conditions differences indicated by significant overall effects,

with alpha set at 0.05.

sented with a word in the middle of the screen

and are required to associate that word with

either of the grouping categories in the top left

or top right of the screen using the E or I keys,

respectively (e.g., for happy pleasant is located

in the top left and unpleasant in the top right).

Response latency to the different pairings is

measured in milliseconds, where positive

scores represent stronger anti-fat or pro-thin

bias (see below for the range of scores included). Response scales for the explicit measures

were a six point likert-type scale from +3 to -3

for the ATOP and BAOP (excluding 0) and 1-5

for both the AFAS and F-Scale. Higher scores

on the AFAS, F-Scale, Q1 and Q2 signify more

negative attitudes and lower scores on the

ATOP and BAOP. The ATOP (e.g., coefficient

of 0.76),21 BAOP ( coefficient of 0.82),21 AFAS

(=0.80)16 and the F-Scale (=0.87)17 have all

been demonstrated to be reliable.

Institutional ethics approval was granted and

informed consent provided by participants.

Data analysis

Apart from the IAT, all total scores for each

measure were calculated and used in analyses.

IAT D scores were calculated as recommen ded,22 representing the difference between

[Health Psychology Research 2013; 1:e24]

Results

Cronbachs alpha calculated across all conditions was acceptable for all explicit measures

(ATOP=0.8, BAOP=0.7, AFAS=0.7, FScale=0.9). Higher IAT D scores (indicating

anti-fat/pro thin bias) were observed in both

experimental conditions compared with baseline (Table 1). Despite the difference in IAT D

scores, there was no significant difference

[F(2, 52) = 1.04, P>0.05]. Attitudes towards

obese persons (ATOP) and the magnitude of

anti-fat attitudes (AFAS) appeared to worsen

in comparison to the baseline when exposed to

the public and celebrity conditions; however

these differences were non-significant: F(2,

52) = 0.41, P>0.05; F(1.5, 37.7) = 1.2, P>0.05

respectively (Table 1). Although non-significant, findings did however suggest that beliefs

about the controllability of obesity (BAOP) and

associating negative characteristics with fatness (F-Scale) improved after exposure to the

public and celebrity images in comparison to

baseline: F(2, 52) = 0.14, P>0.05; F(2, 52) =

0.52, P>0.05 respectively (Table 1).

The only significant effect for explicit attitudes indicated that participants perceived fat

differently in the three conditions [F(2, 52) =

4.69, P<0.05]. Follow-up tests indicated that

fat was perceived as more insulting in the

celebrity condition compared with baseline

conditions [t(27) = -3.22, P<0.01].

[page 123]

Article

on

l

some previous uses of counter-conditioning to

modify other attitudes.26 Additionally, although

celebrities might be perceived positively, this

may not be sufficient to endorse a message to

an audience, as a celebrity is more likely to

have an effect if they are perceived as relevant

to the message being conveyed.9 Thus, the

descriptions used in the celebrity condition

may have detracted from the main message of

reducing anti-fat attitudes where participants

attention may have been focused on the

celebrities achievements as opposed to their

body shape. Final limitations are the lack of

follow up and control for the effect of differentiating participant characteristics. However,

whilst examining the difference of the intervention between BMI categories may have

been useful, previous research (e.g., Puhl &

Brownell)21 has demonstrated that overweight

and obese individuals also report negative attitudes towards obesity, reinforcing the need to

intervene with individuals across the body size

spectrum.

Future research directions

There are a number of potential research

questions to examine as a result of this study.

First, why do individuals develop anti-fat attitudes and why do they appear to be so

ingrained? Second, why do anti-fat attitudes

appear to worsen through exposure to images

of overweight and obese individuals as demonstrated in the present study? Although confirmation is needed, this finding is concerning

and requires attention.

Future research should also examine the

acceptability of anti-fat attitudes, as this may

shed light on why they appear to be resistant to

change, as motivation is a key determinant of

er

ci

al

us

e

Limitations

A limitation of this study that future

research should address is the relatively short

duration of exposure to the images of overweight and obese populations in comparison to

on

-

co

m

Contrary to our hypothesis, exposure to positive images of the obese did not result in more

positive perceptions of obesity; hence, according to the Elaboration Likelihood Model central

and not peripheral processing may be involved

in forming attitudes towards the overweight

and obese 12 The central route involves complex processing meaning attitudes are less

likely to be shaped by underlying messages,

and the peripheral route involves less complex

processing meaning attitudes are more unstable and thus more likely to be altered by underlying messages. Both implicit and explicit attitudes showed little change, or viewed another

way, existing anti-fat attitudes were reinforced, thus endorsing this suggested role of

central processing.

Effective attitude shaping is, however,

dependent on the strength of the underlying

message, which can be increased by length of

exposure to scrutinize the persuasive message.7 Therefore longer exposure to the counter-conditioning manipulation may have yielded results more in line with expectations.

Additionally, motivation is key to attitude

change and which of the two routes of processing is employed.12 Participants motivation to

alter their attitudes was not assessed in this

study, but may help to explain why no change

in attitude was observed. Future research

should measure motivation to change anti-fat

attitudes and where motivation is low employ a

manipulation strategy to modify this, such as

highlighting the negative potential impacts of

holding these attitudes.

Although counter-conditioning interventions have positively influenced racial attitudes in previous research a similar intervention used here to modify anti-fat attitudes did

not produce a positive effect.9 The ineffectiveness of this intervention does however reflect

the limited success of other interventions

aimed at modifying anti-fat attitudes.7

Previous work suggests that negative images

of obese individuals heighten anti-fat attitudes,23 but producing the opposite effect with

positive images appears to be more difficult.

Our results do not inform why this may be the

case but future studies could seek to address

this apparent contradiction (e.g., by monitoring appraisals of the images presented).

As our results indicate that anti-fat attitudes

either did not change or became more negative

following counter-conditioning designed to

improve these, this may suggest that these

attitudes are somewhat robust and resistant to

change. In accordance with previous

research,23 in our sample both implicit and

explicit attitudes were overwhelmingly negative. Our results also support previous findings

that exposure to images of overweight individ-

uals led to increased stigmatization and perceptions of the overweight as lonely, lazy and

teased.24 Swami et al.24 suggest that this is not

surprising, as the more discrepant a body size

is from the perceived societal ideal of physical

attractiveness the more likely stigmatization

and stereotyping is to occur.

Following earlier work,9 we hypothesized

that celebrity images would result in more positive changes in anti-fat attitudes than would

images of the general public. This hypothesis

was not supported, suggesting perhaps that

the association between public status and

desired characteristics observed previously

does not extend to perceptions of obese individuals. This may illustrate that anti-fat attitudes have a different basis from other attitudes (e.g., racial attitudes). For instance, discrimination laws exist against racism and sexism, and skin colour and race are not within

the individuals control. In contrast, no such

legislation currently exists in the United

Kingdom in relation to obesity,25 and this condition is perceived by some as at least under

the individuals partial control of the individual.5 Hence, it may be that anti-fat attitudes

are perceived as more acceptable, making

them more resistant to change, irrespective of

factors such as status that help to facilitate

change in other attitudes. Research that

explores this suggestion and the factors that

contribute to the development of anti-fat attitudes would therefore seem important.

Discussion

[page 124]

Table 1. Means, standard deviation in parentheses and F statistics for explicit and implicit

attitudes in relation to baseline, celebrity and general public conditions.

Measure

ATOP

BAOP

AFAS

F-Scale

Q1

Q2

IAT D score

(m/sec)

Baseline

Celebrity

General public

F (d.f., error d.f)

60.93

(12.95)

12.11

(4.47)

17.45

(3.43)

4.03

(0.47)

7.54

(1.45)

6.50

(2.56)

690

(540)

59.11

(16.94)

12.64

(5.06)

17.93

(3.43)

3.98

(0.50)

8.07

(1.33)

6.64

(2.20)

820

(410)

59.32

(16.87)

12.75

(7.33)

17.71

(3.40)

3.99

(0.47)

7.75

(1.35)

7.11

(2.13)

770

(400)

0.41

(2, 52)

0.14

(2, 52)

1.20

(1.5, 37.7)

0.52

(2, 52)

4.69

(2, 52)

2.1

(1.6, 42.2)

0.36

(2, 52)

ATOP, Attitudes About Obese Persons Scale; BAOP, Beliefs About Obese Persons Scale; AFAS, Anti-Fat Attitudes Scale; F-Scale, The Fat Phobia

Scale short form; IAT: Implicit Attitudes Test modified to assess attitudes towards fatness and thinness; Q1, How insulting do you believe the

word fat is?; Q2, How insulting do you believe the word obese is?

[Health Psychology Research 2013; 1:e24]

Article

References

on

l

1. Dan elsd ttir S, OBrien KS, Ciao A. Antifat prejudice reduction: a review of published studies. Obesity Facts 2010;3:47-58.

2. OBrien KS, Hunter JA, Halberstadt J,

Anderson J. Body image and explicit and

implicit anti-fat attitudes: the mediating

role of physical appearance comparison.

Body Image 2007;4:249-56.

3. Anesbury T, Tiggemann M. An attempt to

reduce negative stereotyping of obesity in

children by changing controllability

beliefs. Health Educ Res 2000;15:141-52.

4. Diedrichs PC, Barlow FK. How to lose

weight bias fast! Evaluating a brief antiweight bias intervention. Brit J Health

Psych 2011;16:846-61.

5. Teachman BA, Gapinski KD, Brownell KD,

et al. Demonstrations of implicit anti-fat

bias: the impact of providing causal information and evoking empathy. Health

Psychol 2003;22:68-78.

6. Gapinski KD, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD.

Can television change anti-fat attitudes

and behavior? J Appl Biobehav Res

2006;11: 1-28.

7. Hague AL, White AA. Web-based intervention for changing attitudes of obesity

among current and future teachers. J Nutr

Educ Behav 2005;37:58-66.

8. OBrien KS, Puhl RM, Latner JD, et al.

Reducing anti-fat prejudice in pre-service

health students: a randomised trial.

Obesity 2010;10:1-7.

9. Dasgupta A, Greenwald AG. On the malleability of automatic attitudes: combating

automatic prejudice with images of

admired and disliked individuals. J Pers

Soc Psychol 2001;81:800-14.

10. Berry TR, McLeod NC, Pankratow M,

Walker J. Effects of biggest loser exercise

depictions on exercise-related attitudes.

Am J Health Behav 2013;37:96-103.

11. Petty RE, Cacioppo JT, Schumann D.

Central and peripheral routes to advertising effectiveness. The moderating role of

involvement. J Consum Res 1983;10:13546.

12. Petty RE, Cacioppo JT. The elaboration

likelihood model of persuasion. In:

Berkowitz L, ed. Advances in social psychology. New York: Academic Press; 1986.

pp 124-181.

13. Wiese HJC, Wilson JF, Jones RA, Neises M.

Obesity stigma reduction in medical stu-

dents. Int J Obesity 1992;16:859-68.

14. Taylor JB. What do attitude scales measure: the problem of social desirability. J

Abnorm Soc Psych 1961;62:386-90.

15. Allison DB, Basile VC, Yuker HE. The

measurement of attitudes toward and

beliefs about obese persons. Int J Eat

Disorders 1991;10:599-607.

16. Morrison TG, OConnor WE. Psychometric

properties of a scale measuring negative

attitudes toward overweight individuals. J

Soc Psychol 1999;139:752-95.

17. Bacon JG, Scheltema KE, Robinson BE. Fat

phobia scale revisited: the short form. Int J

Obesity 2005;25:252-7.

18. Greenwald AG, McGhee DE, Schwartz JLK.

Measuring individual differences in

implicit cognition: the implicit association

test. J Pers Soc Psychol 1998;74:1464-80.

19. Vartanian LR, Herman CP, Polivy J.

Implicit and explicit attitudes towards fatness and thinness: the role of the internalization of societal standards. Body Image

2005;2:373-81.

20. Lane KA, Banaji MR, Nosek BA, Greenwalk

AG. Understanding and using the Implicit

Association Test: IV. In: Wittenbrink B,

Schwartz N, eds. Implicit measures of attitudes. New York: The Guilford Press; 2007.

pp 59-102.

21. Puhl RM, Brownell KD. Confronting and

coping with weight stigma: an investigation of overweight and obese adults.

Obesity 2006;14:1802-15.

22. Greenwald AG, Nosek BA, Banaji MR.

Understanding and using the Implicit

Association Test: an improved scoring

algorithm. J Pers Soc Psychol 2003;85:197216.

23. McClure KJ, Puhl RM, Heuer CA. Obesity

in the news: do photographic images of

obese persons influence antifat attitudes.

J Commun 2011;0:1-3.

24. Swami V, Furnham A, Amin R, et al.

Lonelier, lazier and teased: the stigmatizing effects of body size. J Soc Psych

2008;148:577-93.

25. The Equality Act. Available from: www.legislation.gov.uk.

26. Litcher JH, Johnson DW. Changes in attitudes towards negroes of white elementary school students after use of multiethnic readers. J Educ Psychol 1969;60:14852.

27. James WPT. WHO recognition of the global

obesity epidemic. Int J Obesity 2008;32:

S120-6.

attitude change.8 If anti-fat attitudes are perceived as acceptable, this would also explain

why they are reported in explicit measures.

Qualitative methods to examine how acceptable anti-fat attitudes are and the complexity

of attitude change may shed light on why these

attitudes appear to be more resistant to change

than attitudes towards other physical characteristics.

Finally, the paucity and effectiveness of

attempts to reduce anti-fat attitudes calls for

future research into attitude modification

interventions. This research should endeavour

to overcome the obstacle of robust attitudes by

ensuring that interventions allow individuals

to diligently consider information included and

experience repeated exposure to increase the

likelihood of central as opposed to peripheral

route processing.

on

-

co

m

With the increasing prevalence of obesity in

the United Kingdom,27 this research is timely

and answers the calls for examination of antifat attitude reduction strategies as, to date,

these lack inspection.8 This research has made

an important contribution to this area of

enquiry by suggesting the robustness of antifat attitudes. From a theoretical perspective,

this research provides evidence that anti-fat

attitudes remained resistant to change reflecting those processed through the central route

of the Elaboration Likelihood Model.12

Although this study contributes to the literature examining anti-fat attitude reduction

interventions, this research is still in its infancy. Contrary to our expectations, attitudes were

not improved but worsened, irrespective of the

fact that participants were presented with positive images of obese individuals. Although

support for our hypothesis was lacking present

findings are all the more interesting and

indeed worrying as a result. Our findings raise

questions concerning the route by which antifat attitudes are formed, their apparent robustness, and influences on these attitudes (e.g.,

lack of anti-obesity discrimination legislation

and perceived controllability of obesity). These

appear worthwhile to address in subsequent

studies.

er

ci

al

us

e

Conclusions

[Health Psychology Research 2013; 1:e24]

[page 125]

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Research Presentations of Dietetic Internship Participants: Research Proceedings - Nutrition and Food SectionD'EverandResearch Presentations of Dietetic Internship Participants: Research Proceedings - Nutrition and Food SectionPas encore d'évaluation

- The Impact of Body Diversity Vs Thin-Idealistic Media Messaging On Health Outcomes: An Experimental StudyDocument11 pagesThe Impact of Body Diversity Vs Thin-Idealistic Media Messaging On Health Outcomes: An Experimental Studyaysha fariha100% (1)

- Do Children With Obesity Implicitly Identify With Sedentariness and Fat FoodDocument11 pagesDo Children With Obesity Implicitly Identify With Sedentariness and Fat FoodVarvara MarkoulakiPas encore d'évaluation

- Hajek 2017Document6 pagesHajek 2017lucedejonPas encore d'évaluation

- Validation of The Body Image Life Disengagement Questionnaire 1Document44 pagesValidation of The Body Image Life Disengagement Questionnaire 1Lem BonetePas encore d'évaluation

- Demographic and Psychosocial Correlates of Measurement Error and Reactivity Bias in A Four Day Image Based Mobile Food Record Among Adults With Overweight and ObesityDocument12 pagesDemographic and Psychosocial Correlates of Measurement Error and Reactivity Bias in A Four Day Image Based Mobile Food Record Among Adults With Overweight and ObesityainPas encore d'évaluation

- Is Dieting Good For You?: Prevalence, Duration and Associated Weight and Behaviour Changes For Speci®c Weight Loss Strategies Over Four Years in US AdultsDocument8 pagesIs Dieting Good For You?: Prevalence, Duration and Associated Weight and Behaviour Changes For Speci®c Weight Loss Strategies Over Four Years in US AdultsAdriana MadeiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature Review On Physical Activity and ObesityDocument7 pagesLiterature Review On Physical Activity and ObesitywzsatbcndPas encore d'évaluation

- Synthesis Paper SummativeDocument12 pagesSynthesis Paper Summativeapi-385494784Pas encore d'évaluation

- Jakicic Et Al 2015 ObesityDocument13 pagesJakicic Et Al 2015 ObesityLushy Ayu DistaPas encore d'évaluation

- Article QuestionsDocument2 pagesArticle QuestionsBrian DeanPas encore d'évaluation

- Nova University of Newcastle Research OnlineDocument36 pagesNova University of Newcastle Research OnlineIrisha AnandPas encore d'évaluation

- Physical Activity and Determinants of Physical Activity in Obese and Non-Obese ChildrenDocument11 pagesPhysical Activity and Determinants of Physical Activity in Obese and Non-Obese ChildrenShenbagam MahalingamPas encore d'évaluation

- Review of LiteratureDocument16 pagesReview of Literatureakhils.igjPas encore d'évaluation

- Guevara OTH505 Article3Document5 pagesGuevara OTH505 Article3rubynavagPas encore d'évaluation

- K Winters Lab Report 4Document13 pagesK Winters Lab Report 4api-314083880Pas encore d'évaluation

- Methods in Behavioral Research Qn.1Document4 pagesMethods in Behavioral Research Qn.1Tonnie KiamaPas encore d'évaluation

- Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity and Weight Loss Practice Among Beijing Adults, 2011Document10 pagesPrevalence of Overweight and Obesity and Weight Loss Practice Among Beijing Adults, 2011Aboy GunawanPas encore d'évaluation

- Obesity and Physical Activity Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesObesity and Physical Activity Literature Reviewea8d1b6n100% (1)

- Society's Influence and Perception of Body Image and Appearance 1Document12 pagesSociety's Influence and Perception of Body Image and Appearance 1clrgrillotPas encore d'évaluation

- Television Viewing and Obesity in 300 Women: Evaluation of The Pathways of Energy Intake and Physical ActivityDocument8 pagesTelevision Viewing and Obesity in 300 Women: Evaluation of The Pathways of Energy Intake and Physical ActivityIntanFakhrunNi'amPas encore d'évaluation

- Sedentary Behavior, Physical Inactivity, AbdominalDocument11 pagesSedentary Behavior, Physical Inactivity, AbdominalJose VasquezPas encore d'évaluation

- Changes in The Prevalence of UDocument13 pagesChanges in The Prevalence of UMeccaPas encore d'évaluation

- Health PhyscologyDocument4 pagesHealth PhyscologySera SazleenPas encore d'évaluation

- Original Research ArticleDocument8 pagesOriginal Research ArticleromeofatimaPas encore d'évaluation

- Physical Activity in Pregnancy: A Qualitative Study of The Beliefs of Overweight and Obese Pregnant WomenDocument7 pagesPhysical Activity in Pregnancy: A Qualitative Study of The Beliefs of Overweight and Obese Pregnant WomenBeverly YM ManaogPas encore d'évaluation

- Group 5 - Final SubmissionDocument46 pagesGroup 5 - Final SubmissionHamza AjmeriPas encore d'évaluation

- 2016 Article 1018Document12 pages2016 Article 1018Aditya Lovindo SuwarnoPas encore d'évaluation

- Effectiveness of Facebook-Delivered LifestyleDocument15 pagesEffectiveness of Facebook-Delivered LifestyleJennie Marlow AddisonPas encore d'évaluation

- Ebp Synthesis PaperDocument8 pagesEbp Synthesis Paperapi-404285262Pas encore d'évaluation

- Running Head: RESEARCH PROPOSAL 1Document10 pagesRunning Head: RESEARCH PROPOSAL 1hjogoss0% (1)

- Shereen Richard Poster PresentationDocument1 pageShereen Richard Poster Presentationapi-281150432Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Social Comparison and Body ImageDocument3 pagesThe Social Comparison and Body ImageOmilabu LovethPas encore d'évaluation

- QoL Obese ChildrenDocument7 pagesQoL Obese ChildrenLiga Sabatina de BaloncestoPas encore d'évaluation

- PTRJ 6weekcorestability 2016-2Document10 pagesPTRJ 6weekcorestability 2016-2Ewerton ElooyPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychology JournalDocument36 pagesPsychology JournalMarisa KwokPas encore d'évaluation

- Bidirectional Relationships Between Weight Stigma and Pediatric Obesity A Systematic Review and Meta AnalysisDocument12 pagesBidirectional Relationships Between Weight Stigma and Pediatric Obesity A Systematic Review and Meta Analysislama4thyearPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal Referat 2Document7 pagesJurnal Referat 2nunki aprillitaPas encore d'évaluation

- School Based Physical Activity Intervention To Reduce Obesity and Increase Physical Fitness Obese Elementary ChildrenDocument9 pagesSchool Based Physical Activity Intervention To Reduce Obesity and Increase Physical Fitness Obese Elementary ChildrenAthenaeum Scientific PublishersPas encore d'évaluation

- As e Perda de PesoDocument9 pagesAs e Perda de PesoAntónio João Lacerda VieiraPas encore d'évaluation

- TEXTO4Document14 pagesTEXTO4Josimar FoganholiPas encore d'évaluation

- Research PaperDocument10 pagesResearch PaperAndrielle Keith Tolentino MantalabaPas encore d'évaluation

- Child Health - Childhood Obesity Leads To Lack of Exercise Not Other Way Round Says New Research (Medical News Today-9 July 2010)Document3 pagesChild Health - Childhood Obesity Leads To Lack of Exercise Not Other Way Round Says New Research (Medical News Today-9 July 2010)National Child Health Resource Centre (NCHRC)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Final Cat BaileysolheimDocument9 pagesFinal Cat Baileysolheimapi-314552584Pas encore d'évaluation

- Postpartum Behaviour As Predictor of Weight Change From Before Pregnancy To One Year PostpartumDocument8 pagesPostpartum Behaviour As Predictor of Weight Change From Before Pregnancy To One Year PostpartumJm OpolintoPas encore d'évaluation

- RM SanaDocument13 pagesRM SanaMuhammad AbdullahPas encore d'évaluation

- Ehealth Interventions To PromoDocument90 pagesEhealth Interventions To PromoNs. Dini Tryastuti, M.Kep.,Sp.Kep.,Kom100% (1)

- Argumentative Essay 2021Document7 pagesArgumentative Essay 2021api-598322297Pas encore d'évaluation

- MD7069 PPT NotesDocument6 pagesMD7069 PPT NotesJotPas encore d'évaluation

- WomenDocument3 pagesWomenamarkumar42012Pas encore d'évaluation

- Familia y Control de Obesidad - InglesDocument11 pagesFamilia y Control de Obesidad - InglesAlejandra Bedregal TissieresPas encore d'évaluation

- 22 Depression Alliance Abstracts, July 09Document6 pages22 Depression Alliance Abstracts, July 09sunkissedchiffonPas encore d'évaluation

- Annotated BibliographyDocument9 pagesAnnotated Bibliographyapi-665390379Pas encore d'évaluation

- Final Draft W PaperDocument27 pagesFinal Draft W Paperapi-391688113Pas encore d'évaluation

- CASP Qualitative Appraisal Checklist 14oct10Document12 pagesCASP Qualitative Appraisal Checklist 14oct10Agil SulistyonoPas encore d'évaluation

- An Intervention For Improving The Lifestyle Habits of Kindergarten Children in Israel: A Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trial InvestigationDocument8 pagesAn Intervention For Improving The Lifestyle Habits of Kindergarten Children in Israel: A Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trial InvestigationRiftiani NurlailiPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Paper On Obesity in IndiaDocument4 pagesResearch Paper On Obesity in Indiaukldyebkf100% (1)

- Body Image: Doeschka J. Anschutz, Rutger C.M.E. Engels, Eni S. Becker, Tatjana Van StrienDocument7 pagesBody Image: Doeschka J. Anschutz, Rutger C.M.E. Engels, Eni S. Becker, Tatjana Van StrienAnonymous QvyQefPas encore d'évaluation

- Makale 3Document8 pagesMakale 3Beste ErcanPas encore d'évaluation

- tmp3CAB TMPDocument16 pagestmp3CAB TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmp6F0E TMPDocument12 pagestmp6F0E TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmpEFCC TMPDocument6 pagestmpEFCC TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmpCE8C TMPDocument19 pagestmpCE8C TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmp80F6 TMPDocument24 pagestmp80F6 TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmpF178 TMPDocument15 pagestmpF178 TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- Tmp1a96 TMPDocument80 pagesTmp1a96 TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmpE3C0 TMPDocument17 pagestmpE3C0 TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- Tmpa077 TMPDocument15 pagesTmpa077 TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmpFFE0 TMPDocument6 pagestmpFFE0 TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmpE7E9 TMPDocument14 pagestmpE7E9 TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmpF407 TMPDocument17 pagestmpF407 TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmpF3B5 TMPDocument15 pagestmpF3B5 TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmp72FE TMPDocument8 pagestmp72FE TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmp6382 TMPDocument8 pagestmp6382 TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmpD1FE TMPDocument6 pagestmpD1FE TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmpC0A TMPDocument9 pagestmpC0A TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmp4B57 TMPDocument9 pagestmp4B57 TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmp60EF TMPDocument20 pagestmp60EF TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmp998 TMPDocument9 pagestmp998 TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmp8B94 TMPDocument9 pagestmp8B94 TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmp37B8 TMPDocument9 pagestmp37B8 TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- Tmp75a7 TMPDocument8 pagesTmp75a7 TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmpA0D TMPDocument9 pagestmpA0D TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmp9D75 TMPDocument9 pagestmp9D75 TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmpB1BE TMPDocument9 pagestmpB1BE TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmp2F3F TMPDocument10 pagestmp2F3F TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmp27C1 TMPDocument5 pagestmp27C1 TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmpC30A TMPDocument10 pagestmpC30A TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- tmp3656 TMPDocument14 pagestmp3656 TMPFrontiersPas encore d'évaluation

- BMI ClassificationDocument2 pagesBMI ClassificationJesse FlingPas encore d'évaluation

- Food A Healthy Diet WorksheetDocument1 pageFood A Healthy Diet WorksheetRaquel LagePas encore d'évaluation

- Capstone Research PaperDocument5 pagesCapstone Research Paperapi-371069119Pas encore d'évaluation

- Soft DietDocument3 pagesSoft DietkitsilcPas encore d'évaluation

- Isearch Paper Draft 1Document14 pagesIsearch Paper Draft 1api-283977895Pas encore d'évaluation

- Describing People: Look at Your Teacher: HEIGHT / WEIGHTDocument1 pageDescribing People: Look at Your Teacher: HEIGHT / WEIGHTinmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Oil Palm Fractions Derivatives Web PDFDocument6 pagesOil Palm Fractions Derivatives Web PDFIan RidzuanPas encore d'évaluation

- Preterm Birth ReviewDocument17 pagesPreterm Birth ReviewfahlevyPas encore d'évaluation

- Thai Food Good Set Menu For HealthDocument82 pagesThai Food Good Set Menu For HealthChulawatchara100% (1)

- Take It Off Keep It OffDocument228 pagesTake It Off Keep It OffDawson EllisonPas encore d'évaluation

- Intermittent Fasting GuideDocument8 pagesIntermittent Fasting GuideTech On Demand Solution Providers50% (2)

- BreastfeedingDocument30 pagesBreastfeedingqueennita69100% (5)

- Elc 030 (Week 2)Document21 pagesElc 030 (Week 2)ahmad mukhlisPas encore d'évaluation

- Hypertension in PregnancyDocument20 pagesHypertension in PregnancyRelly Arevalo-AramPas encore d'évaluation

- Pedia StickersDocument8 pagesPedia Stickersmkct111100% (1)

- Health Improvement Benefits ApprovalDocument1 pageHealth Improvement Benefits ApprovalPloverPas encore d'évaluation

- Ervina Damayanti-31210005-DIV MIK-T Singkatan KodingDocument3 pagesErvina Damayanti-31210005-DIV MIK-T Singkatan KodingErvina DamayantiPas encore d'évaluation

- Diabetes Medical Management PlanDocument6 pagesDiabetes Medical Management PlanjennmoyerPas encore d'évaluation

- 9 Unknown High Cholesterol Symptoms!Document2 pages9 Unknown High Cholesterol Symptoms!Feronica Felicia Imbing IIPas encore d'évaluation

- Adequacy of Perfusion During Cardiopulmonary BypassDocument64 pagesAdequacy of Perfusion During Cardiopulmonary BypassBranka Kurtovic50% (2)

- Food AdvertisingDocument306 pagesFood AdvertisingaquarianchemPas encore d'évaluation

- Natures Hidden Health MiracleDocument38 pagesNatures Hidden Health MiracleGorneau100% (2)

- Obesity in MalaysiaDocument1 pageObesity in MalaysiaPapa KingPas encore d'évaluation

- Fast Food Consumption and Its Impact On Health: ArticleDocument10 pagesFast Food Consumption and Its Impact On Health: ArticleabjithPas encore d'évaluation

- Client Role - Mrs Maria FierroDocument4 pagesClient Role - Mrs Maria Fierroapi-271284613Pas encore d'évaluation

- Class 3 Dps Evs Enrichment 2019Document3 pagesClass 3 Dps Evs Enrichment 2019ArchanaGuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature Review 1 1Document5 pagesLiterature Review 1 1api-625944833Pas encore d'évaluation

- FDArticle 2Document2 pagesFDArticle 2Mpampis XalkidaPas encore d'évaluation

- CANCER Registry FormDocument4 pagesCANCER Registry Formcar3laPas encore d'évaluation

- Study of Oxlate Ion in Guava FruitDocument19 pagesStudy of Oxlate Ion in Guava FruitArpit Shringi70% (56)