Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Muthos and Logos Mythical Themes and Structures in The Philosophy of Empodocles by Mark Lamarree

Transféré par

Uncondemning MonkTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Muthos and Logos Mythical Themes and Structures in The Philosophy of Empodocles by Mark Lamarree

Transféré par

Uncondemning MonkDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

1

Muthos and Logos:

Mythical themes and structures

in the Philosophy of Empedocles

...with Empedocles -[this Pythagorean philosophy] had

become well and truly Bacchic" (Plutarch, De gen. Socr.

580c)

The relationship between muthos1 and logos2 in the theogonies and

cosmologies of Ancient Greece range from the relatively straightforward mythos of

anthropormorphic gods of Homer and Hesiod to the rejection of muthos in favour of

strict logos adopted by Aristotle. During that period, there was a complex, dynamic

interaction between muthos and logos as a nascent rational tendency was emerging

with the birth of philosophy.3 It has been observed that Greek myths, in Homer and

Hesiod, for example, function according to a coherent system of thinking. The

premises that they are based on (albeit not founded on rational logic) follow a

consistent logical pattern (Adkins 95-103).4 Many comparative structuralist-oriented

schools of mythological theory have demonstrated the structural coherence of

myths from a symbolic perspective, be it from a social, psychological, or theological

interpretation.5

Hesiods Theogony, essentially a muthos, can be seen to demonstrate a

coherent effort at assembling and organizing narrative material to form a

In the context of this paper, the definition for muthos will be: fantastic narrative.

In the context of this paper, the definition for logos will be: rational explanation.

3

For an analysis of the relationship between poetry and philosophy during this period, see part I of Cornfords

Principium Sapientiae.

4

From the linguistic perspective, Raymond Adolph Prier recognizes a form of logic based on the grammatical

structures of Presocratic thinking and poetry such as the HomericHymns. Taking the symbolic logic theories of

Ernst Cassirer, he notices a symbolic dyadic structure based on notions of opposites and a unifying third term. He

calls this Archaic Logic.

5

For a discussion of several leading mythical theorists such as Ernst Cassirer, Claude Lvi-Strauss, Sigmund Freud,

and Carl Jung, see Kirks Myth Its meaning and function, pp. 261-85.

2

comprehensive explanation of the world.6 7 Cornford has compared Hesiods

Theogony with the structure of the first book of Genesis (199-200).8

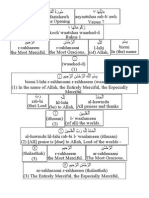

Genesis

Hesiod

1- Earth without form and void,

darkness on face of the deep, spirit

of God moved on face of waters,

light appeared, divided from

darkness as day and night

2- Heaven as roof to divide

heavenly waters, rain

3- Dry land separated from seas,

grass and trees

Earth and Eros, then Night gave birth to

Day

Earth generates Heaven as set for

gods, shell of world-egg

Earth generates hills and sea (Note that

Empedocles made the trees, the first

living creatures, spring up from the

earth like embryos in the mothers

womb, before the sun existed

4- Sun, moon, stars created to

Earth and Eros, then Night gave birth to

divide day and night, seasons, days, Day In Greek cosmogonies heavenly

years

bodies are formed later than the earth

5- Waters bring forth the moving

In Anaximander, action of the suns

creatures

heat on moisture reproduce in physical

terms Hesiods marriage of heaven and

Earth.

6- Male and female created to be

fruitful

Pherekydes theogony (ca. 550 B.C.) demonstrates a capacity for

independent creative thinking in reformulating mythical material from various

sources in an original way (Kirk, Raven & Schofield 71). The Spartan poet Alcman

At all events Hesiod, treating all these deities as intelligent and anthropomorphic, and linked by bonds formed by

blood, marriage, and political alliance, constructs in the Theogony, when combined with the Works and Days, a

framework within which the whole of the visible world, and anything which happens to anyone in that world, can

be explained. I do not seek to persuade my readers that Hesiod is an unappreciated philosopher, simply that

sustained intellectual effort in the interest of synthesis and comprehensible order maybe expended by those who are

not philosophers (Adkins103).

7

Tate maintains that conceptual perspectives are no less embodied in mythical narrative than in philosophical

assertion. These narratives could not take the form that they do unless truth were conceived fundamentally as a

ground, an aition, a lighting up of context that makes possible speaking and being (58).

8

The process is the same as in Greek cosmogonies-separation or differentiation out of a primitive confusion. As

measured by the absence of personifications, Genesis I is less mythical than Hesiod, and even closer to the

rationalized system of the Milesians (Cornford 200).

(600 BC) presents a theogonic poem that has more abstract concepts related to the

formation of primal substances (47-48).

With the emergence of Presocratic philosophy, beginning with the Milesian

school, theogonical speculation gives way to natural cosmological speculation.

However the muthos of the theogonies and the logos of the Presocratics, in certain

instances were not mutually incompatible. The example of the Derveni papyrus has

an Orphic cosmogony accompanied by exegetical commentary containing physical

explanations in terms reminiscent of Anaximander, Diogenes and Heraclitus (Laks

126-27). The Theogony is therefore viewed as an allegory that contains explanations

of the causes of natural phenomena.9 With the Presocratic philosophers, much of the

mythical aspects have been eschewed, yet prevalent mythical structures and

religious conceptions remain.10

The gods are no longer portrayed as anthropomorphic but rather are

perceived as creative and active natural forces and substances. It could be

considered that there subsisted a basic world view generally adopted by most of the

Presocratics that reflected an established mythically-influenced world view. 11

According to Aristotle, "this (elementary matter), they say, is the divine; for it is

immortal and indestructible, as Anaximander and most of the natural philosophers

maintain." (3Phys. iii. 4. 203 b I3. 91 qtd. in Guthrie 91).

His physics, philosophically refined as it may be, is minimalist, because it is subordinated to a theological thesis

that culminates in the affirmation of divine rationality. This by itself would be enough, I think, to explain why the

Derveni author could be led to assume that the Orphic theogony and Presocratic philosophy were saying the same

thing, and to understand the use he makes of allegory (Laks 138)

10

And there are in fact significant precedents in early Greek thought for such a mixture of mystery religion with

natural philosophy. Pythagoras himself seems to have borrowed the outlines of his cosmology from the Milesian

physicists. We find elemental physics crossed with mystic immortality in the doctrine of Heraclitus that we live the

death of the gods and they live our death. (b77 b62) The metaphysics and the cosmology of Parmenides are cast in

the form of a supernatural vision vouchsafed him on a journey to the realm of Light (Kahn 427).

11

According to Tate, Pre-Socratic cosmologies are clearly developed from these earlier cosmologies, which they

resemble structurally.The divine agencies in these earlier cosmologies have simply been replaced by the more

"conceptual" agencies of Love, Hate, Nous, the Unlimited, and so on. (51).

Furthermore, one can notice a form of pantheism in the doctrines of the

Milesians and Heraclitus, similar to the pantheism found in Orphism;12 moreover

their theories are commonly constructed on analogies with human social and

political functions;13 and there appears to be a common presence of some form of

divine mind, related to air and fire.14 Cornford, in analysing the cosmology of

Anaximander, posits a basic structure common to all Ionian cosmological theory

(189):15

(1)In the beginning there is a primal Unity, a state of indistinction or fusion in

which factors that will later become distinct are merged together.

(2)Out of this Unity emerge, by separation, pairs of opposite things or powers;

the first being the hot and the cold, then the moist and the dry. This

separating out finally leads to the disposition of the great elemental masses

constituting the world-order, and the formation of the heavenly bodies.

(3)The Opposites interact or reunite, in meteoric phenomena and in the

production of individual living things, plants and animals. 16

12

The pantheistic character of this conception of Zeus is obvious. My conclusion is that the Milesians and

Orphics shared a pantheisitic idea and combined it with a "historical view" of the universe: pantheism was

cosmogonical in the Milesians and theogonical in the Orphics (Finkelberg 325). The doctrine of Heraclitus, like

that of the Milesians, is cosmogonical pantheism (328).

13

The cosmology of Empedocles shares with its predecessors, the cosmologies of Ananximander or Heraclitus, a

feature characteristic of all Greek cosmological thought: the interpretation of natural processes by means of

analogies taken from mans political and social life (Jaeger 139).

14

If I do not see the need to associate myself with the accusation, it is because the doctrine in question is one

which we have already found in such diverse pre-Platonic thinkers as Anaximenes, the Orphics and Diogenes of

Apollonia, and could find also (on Aristotle's testimony) in Democritus; the doctrine, namely, that there is an

immortal mind-stuff of which mortal creatures acquire a tincture by breathing it in either as air itself or with the air.

Heraclitus, then, said Sextus (Diels-Kranz A i6, vol. i, p. I48), held that "what surrounds us" is rational and endowed

with mind, and this divine reason (logos), according to him, we draw in by breathing and thus become thinking

creatures ourselves(Guthrie 96).

15

Hence Aristotle assigns Anaximander to the second class,who say that, out of their unity, the Opposites

contained in it are separated out as Anaximander says (phesi).This class also contains the pluralists who came

after, such as Empedocles and Anaxagoras. These start with a plurality of distinct things in a single mixture, in

which they were -separated out- (161).

16

Similarly Bollack sees a five-part structure in Empedocles cosmological system : 1-Being in its integrity and

perfection (the sphere); 2- Rupture of the unity of the sphere; 3- The origin of the world: the phase of separation; 4Return to the One: the birth of mixture; 5- The period of mixtures: the composition of life. Return to the One. (173)

With Empedocles, the qualities of a creative religious, mytho-poetic

imagination fluent in Homer, Hesiod, Pindar, and Parmenides allies itself with a

rational mind keenly interested in understanding the natural world :

The first condition for an understanding of Empedocles is to banish the

notion of a gulf between religious beliefs and scientific views. His work is a

whole, in which religion, poetry, and philosophy are indissolubly united. His

imagination is constructive, gathering elements from every available quarterHesiodic and Ionian cosmogony, Parmenidean rationalism, Orphic mysticism,

poetic legend, the experience of a physician, a poets sensuous response to

the sights and sounds of mature, and the fears and hopes of a spirit exiled

from heaven for a brief span of life that is not life- but building all these

elements together into a unitary vision of the life of the world and the

destiny of the human soul, bound, like the macrocosm, upon the wheel of

birth and death (Cornford 122).

To give an idea of how Empedocles articulates the elements of muthos and

logos in his system,17 eleven fragments have been chosen in an attempt to illustrate

the basic aspects of his system:18

1- For if, immortal muse, for the sake of any ephemeral creature, [it has

pleased you] to let our concerns pass through your thought, answer my

17

Seen against this background, Empedocles procedure can be described as follows: he combines, within one and

the same poem, the two established poetical modes of referring to the divine, that is, both the mythological and the

philosophical one, so that they are mirrored in each other (Primavesi 257).

18

Pierris gives an interesting structural guideline: Religion, philosophy and physics or, in alternative

formulation, dimensions of awareness first mythological/symbolic, second metaphysical/speculative and third

scientific /experiential must be kept in unison, considered as forming an integral of the manifestation of being, of

the revelation of the hidden in reality (189).

prayers again now, Calliopeia, as I reveal a good discourse about the

blessed gods (131, Inwood 215)

It is traditional among poets to call to the Muses (the nine goddesses who

presided over the arts, governed by Apollo). Calliopeia is the muse who presides

over epic poetry. Like Parmenides, Empedocles adopts the traditional religious

esthetics to present his philosophy in poetic form. 19 A formal cult dedicated to the

Muses became an active feature in the schools of Plato, Aristotle, Epicurus (possibly)

and in the later Neoplatonist schools.20

221- Eudemus understands the immobility to apply to the Sphere in the

supremacy of Love, when all things are combined there neither are the

swift limbs of the sun distinguished, but, as he says, thus It is held fast in

the close obscurity of Harmonia, a rounded sphere rejoicing in its joyous

solitude. But as Strife begins to win supremacy once more, then once more

motion occurs in the Sphere: For one by one all the limbs of the god began

to quiver. (27, 31) 295

The Sphere/Harmony Love Strife threefold conception forms the heart of

Empedocles metaphysical system. Love represents the force of unity of bringing

things together, mixing the four elements22 to form the universe. In Hesiods

19

From the very beginning we have stressed the fact that there is no unbridgeable gulf between early Greek poetry

and the rational sphere of philosophy. The rationalization of reality began even in the mythical world of Homer and

Hesiod, and there is still a germ of productive mythopoetic power in the Milesians fundamentally rational

explanation of nature. In Empedocles this power is by no means diminished by the increasingly complex apparatus

of his rational thought, but seem to increase proportionally, as if striving to counteract the force of rationalism and

redress the balance (Jaeger 133).

20

See Boyancs Le culte des muses chez les philosophes grecs : tudes d'histoire et de psychologie religieuse.

21

Reference to the fragments will follow the Diels-Kranz numbering, with page numbering from Kirk, Raven

&Schofield.

22

Aristotle remarks that one might suspect that the need for a moving cause was first felt by Hesiod and by

whoever else posited love or desire as a principle among things, for example Parmenides, on the ground that there

must exist some cause which will move things and draw them together, (sunaxei, Met. A4, 984b 23). The Love of

Empedocles has the same function of uniting unlike or opposite elements. Aristotle was not slow to recognize the

mythical or poetical antecedents of philosophical concepts (Cornford 196).

Theogony, Eros is present as one of the first gods (120), with the implicit recognition

that the erotic function plays an important cosmological role (Hershbell 153).

The notion that Strife, causing separation and dissolution of the elements, in

a cyclical movement following loves mixing together, is present in Hesiods Works

and Days (11-26) as a significant force in humanitys social life. Proclus (238) relates

the action of Empedocles strife to the war of the Titans in Hesiods Theogony. A

certain resemblance of Love and Strife and the relationship between Aphrodite and

Ares in Homeric myth is perhaps noticeable. They are said to have had a daughter

named Harmonia. The relation to the Homeric myth had been noted by the ancient

mythographer Heraclitus (ca. 1st c. AD):

For Homer seems to confirm the dogmas of the Sicilian school and the doctrine of

Empedocles by calling strife (neikos) Ares and love (philia) Aphrodite. And he brings

them into his poem, though they were originally at variance, united together after

their ancient rivalry (philoneikia) in one accord. So with good reason Harmonia was

born from these two since everything was joined together (harmosthenai) tranquilly

and harmoniously (Trzaskoma, Smith, & Brunet 119).

Burkert notices a resemblance to a mythical dualism from Iranian

mythology.23 Empedocles uses the image of limbs repeatedly, evoking a certain

anthropomorphic reference. The activation of limbs possibly refers to the

manifestation of physical elements, the material world thus being equated with

embodiment.

23

As for the Presocratics, it is Empedocles who is developing a kind of dualism, as he explains what is going on in

nature b the antagonism of two principles or gods, Philia and Neikos, the one positive and sympathetic, the other

absolutely negative, disastrous, hateful. And Empedocles makes the conflict a battle, regulated by predestined time,

with Neikos jumping up to take the rule in the fulfillment of time(B30). This is a piece of mythology that

seems to be unnecessary in the system: modern interpreters would prefer to have continuous interaction between the

two principles, instead of the phases of a cycle and a sudden jump to power. Has it been motivated by the

Zoroastrian myth, the attack of Angra Mainyu on Ahura Mazda? (Burkert 74).

3- For he is not furnished with a human head upon limbs, nor do two

branches spring from his back, he has no feet, no nimble knees, no shaggy

genitals, but he is mind alone, Holy and beyond description, darting through

the whole cosmos with swift thoughts. (134, 312)

The presence of a divine mind is evoked and the non-anthropomorphic

aspect is emphasized, possibly in contradistinction to the traditional Homeric myth.

It is given a certain descriptive characterization, perhaps evoking the god Hermes.

Primavesi posits the Empedocles is referring to Apollo. 24

4- Hear first the four roots of all things: shining Zeus, life-bringing Hera,

Aidoneus and Nestis who with her tears waters mortal springs. (6, 286)

And earth chanced in about equal quantity upon these, Hephaestos, rain,

and gleaming air, anchored in the perfect harbours of Cypris, either a little

more of it or less of it among more of them. From these arose blood and the

various forms of flesh. (98, 302)

Theophrastus distributes the elemental qualities to the gods thus:

Zeus

Fire

Hera

Air

Aidoneus

(Hades)

Earth

Nestis

(Persephone)

Water

The anthropomorphism of spiritual powers changes to personification of

spiritual substances. In general, the elements are related to traditional attributes of

the corresponding divinity.25 Moreover, there is a male/female oppositional

polarization, that is so important in Empedocles system. Zeus and Hera form a

24

Unlike the case of the four pre masses, a mythical name of the remaining long-lived gods, that is the Sphairos,

has not been preserved within the surviving fragments themselves. But the introductory comment of Ammonius on

B134 pre-supposes that Empedocles designated the Sphairos quite unambiguously as Apollo (Primavesi 258).

25

The four elements have their basic distinguishing names, for example, fire or water. In addition, they can take

on the names given to deities in the traditional belief systems; they are the equivalents of those deities, absorbing

the representations of the power that had been attached to gods (Bollack 55).

couple; and if the Sicilian tradition of equating Nestis with Persephone is considered

(Kingsley 382), the couple of Hades and Persephone is established. Another

contrasting opposition, between celestial couple and underworld couple, could be

observed.

The elements of Empedocles are said to each have their own domain. This

notion can be seen in part in Homeric myth, where the three brothers Zeus,

Poseidon and Hades preside over the celestial, terrestrial, and underworld regions

respectively.26

5- There were Earth and far-seeing Sun, bloody Discord and Serene

Harmonia, Beauty and Ugliness, Haste and Tarrying, lovely Truth and blind

Obscurity. (122)

Here is an enumeration of cosmogonic elements in Empedocles account of

the universe, and there is a certain personification. There are similar lists of

conceptual personifications in Hesiod Theogony, for example, the progeny of Night

(211-40), the main difference being that Empedocles presents them as opposites,

thus furnishing a philosophical sense of balance into his system.

6- There is an oracle of Necessity, ancient decree of the gods, eternal, sealed

with broad oaths: when anyone sins and pollutes his own limbs with

bloodshed, who by his error makes false the oath he swore spirits whose

portion is long life for thrice ten thousand years he wanders apart from the

blessed, being born throughout that time in all manner of forms of mortal

things, exchanging one hard path of life for another, The force of the air

pursues him into the sea, the sea spews him out onto the floor of the earth,

the earth cast him into the rays of the blazing sun, and the sun into the

26

Each is a master in a different province and each has its own character(B17.28)

10

eddies of the air; one take him from the other, but all abhor him, Of these I

too am now one an exile from the gods and a wanderer, having put my trust

in raving Strife. (115, 315)27

Necessity is presented as a philosophical principle in the Universe and is here

given a certain personification, as it has an active agency, delivering oracles to the

gods. The exile of the daimon (spirit) is due to an original sin. Symbolically, the fall

represents the incarnation of the soul in the material world, a fall from grace.

28

The

fall is a mythical/religious notion, one can think of the fall of Lucifer (Isa. 14:12-14).

This notion is closely related to the notion of original sin; one can think of the fall of

Adam in Genesis (3:1-24)29, and also the story of Cain and Abel (4:1-16). Elements

are present in the myth of Prometheus, as well, in a story where humanity once

dined at the gods banquet table (Harris & Platzner 109). Here Empedocles mythical

presentation is integrated into his system as the individual immerses them in the

elements in the process of falling, and Strife is seen as an agent of this process of

incarnation. Cornford compares the process of transformation into each of the

elements with transformation motifs in Celtic mythology. 30 Primavesi terms this

concept in Empedocles as the cycle of the guilty god.31

27

This personification of destructive forces is similar to Hesiods Theogony(211-226) : I wept and wailed when I

saw the unfamiliar place where Murder and Anger and tribes of other Deaths they (sc. The daimones) wander in

darkness over the meadow of Doom. (118, 121)

28

A divine potency stripped, for an aeon, of his divine identity: this is the Empedoklean daimon (Zuntz 271).

29

Osborne briefly compares the fall of the daimon with the fall of Adam (294).

30

For example, in the Welsh Book of Taliesin: I have been a journey (?), I have been an eagle, I have been a sea

coracle I have been a sword in the hand, I have been a shield in battle, I have been a string in harp(122).

31

As soon as Apollos mortal incarnations are identified as the paradigm of thecycle of the guilty god, we

observe striking parallels between that cycle and the myth told about Apollo in the Hesiodic Catalogue of Women

and alluded to by Aeschylus: Asclepius, Apollos son by Coronis, had used his healing powers to restore the dead to

life, and for this had been blasted to death by the thunderbolt of Zeus, forged by the Cyclopes. Apollo in revenge

killed the Cyclopes, and was sentenced by Zeus to a term of penance as serf to a mortal, Admetus. After that, he

returns to the other Olympians (Primavesi 262).

11

7- Empedocles held that the first generations of animals and plants were not

complete but consisted of separate limbs not joined together; the second,

arising from the joining of these limbs, were like creatures in dreams; the

third as the generation of whole-natured forms; and the fourth arose no

longer from the homogenous substances such as earth or water, but by

intermingling, in some cases as the result of the condensation of their

nourishment, in others because feminine beauty excited the sexual urge; and

the various species of animals were distinguished by the quality of the

mixture in them (96, 303)

The notion of multiple generations of evolution is akin to the mythical notion

of the five ages found in Hesiods Works and Days (110-202). Cornford and West

consider Empedocles explanation of sexual generation to be related to the mythical

theme of the splitting of an original bi-sexed figure (208).

32 33

The evolution of plants

and animals (and conceivably humans) in Empedocles follows certain stages that

are significantly distinctive one from the other.34

8- Among them was no war-god Ares worshipped, nor the battle-cry, nor was

Zeus king nor Kronos nor Poseidon, but Cypris was queen. Her they

propitiated with holy images, with paintings of living creatures, with

perfumes of various fragrances and sacrifices of pure myrrh and sweet-

32

The Zohar, whether independently or not, has here presented the myth of the separation of male and female by

the splitting of an original bisexed figure, parallel to the separation of Father-Heaven and Mother-Earth from a

single form. This myth lies behind Aristophanes speech in the Symposium and Empedocles whole-natured forms,

which, in the period of world-formation by strife, are divided into two sexes (Cornford 208).

33

According to Empedocles (B62, 63) the sexes were produced by division of whole-natured creatures, who

were themselves evolved from earlier forms of life. According to the Brhadaranyaka Upanishad, 1.4. 1-3, the

universe began as the Self in human form. He was lonely and bored. Now he was the size of a man and a woman

in close embrace. He split this Self in two, and from this arose husband and wife (West 235).

34

We may recall that Empedocles indeed associated the two halves of the plant with specific elements and

motions: he took fire to be a component of the green part of the plant, earth of its root, the two elements accounting

for the respective motions upward and downward. (In relation to Anaximander, Empedocles of course inverted

explicandum and explanans(Freudenthal 215).

12

scented frankincense, throwing to the ground libation soft yellow honey. The

altar was not drenched by the unspeakable slaughters of bulls, but this was

held among men the greatest defilement to tear out the life from noble

limbs and eat them. (128, 318)

In this example, the comparison to Hesiods five ages is more explicit.

Reference to Hesiods first period, the Age of Gold is alluded to (111-125). 35

Here Empedocles contrasts the traditional mythological and religious

conceptions with his own views of religious purity, the prohibition of blood

sacrifice related to his eschatological conception.

9- Many creatures were born with faces and breasts on both sides, manfaced ox-progeny, while others again sprang forth as ox-headed offspring of

man, creatures compounded partly of male partly of the nature of female,

and fitted with shadowy parts. (61, 304)

This notion of monstrous creatures at a primitive period of evolution has

echoes in the Cyclops, Titans, and Giants in Hesiods Theogony. Various half-human,

half-animal creatures can be found in Greek mythology, such as the Centaurs and

the Minotaur. Empedocles is giving a natural history account, but he seems to make

allusion to mythical concepts when describing more primitive phases in his scheme.

Another early phase of human development, contains a notion present in mythology,

humans being born from the earth, for example in the myth of Deucalion (Harris &

Platzner 125):

Come now, hear how fire as it was separated raised up the nocturnal shoots of me

and pitiable women: it is no erring nor ignorant tale. Whole-natured shapes first

sprang up from the earth, having a portion of both water and heat. There fire sent

35

The myth is recast in the light of that interpretation. Hesiods narrative of the Golden and the following Ages

provided the basic concept of progressive deterioration and is called to mind by characteristic details both material

and verbal (Zuntz 259).

13

up. Wishing to come to its like: they did not yet display the desirable form of limbs

nor voice, which is the part proper to men (62, 304).

10- Her must you contemplate with your mind, and sit with eyes dazed: she

it is who is thought innate even in mortal limbs, because of her they think

friendly thoughts and accomplish harmonious deeds, calling her Joy by name

and Aphrodite. She is perceived by no mortal man as she circles among

them: but you must listen to the undeceitful ordering of my discourse. (17,

289-90)36

Love, Philotetes, so important in Empedocles system, is seen to display

noticeable characteristics of Aphrodite, as her powers of mixture are shown to act in

the human sphere. There are parallels in Hesiods Theogony (205), were Aphrodite is

seen to influence the life of humans (Hershbell 153).

11- But at the end they come among men on earth as prophets, bards,

doctors, and princes; and thence they arise as gods highest in honour,

sharing with the other immortals their hearth and their table, without part in

human sorrows or weariness. (146, 317)

In the salvation aspect of Empedocles eschatological concept, mankind must

free himself from the cycle of reincarnations by purification until one becomes divine

oneself and rejoins the gods.37 This possibly indicates Orphic38 and Pythagorean

36

Another reference to Cypris demonstrates her demiurgic role, fashioning the human eye with a mixture of

elements: As when someone planning a journey through the wintry night prepares a light, a flame of blazing fire,

kindling for whatever the weather a linen lantern, which scatters the breath of the winds when they blow, but the

finer light leaps through outside and shines across the threshold with unyielding beams, so at that time did she give

birth to the round eye, primeval fire confined with membranes and delicate garments, and these held back the deep

water that flowed around, but they let through the finer fire to the outside (84, 3-8).

37

The impact of destructive Neikos upon the supramundane realm of the gods; expulsion of the transgressor, who

forfeits his divine status and cut off from his heavenly origin, must undergo toil upon toil, but finally, on completing

his penance, is readmitted to his primordial demesne: it is evident that here is the inspiration for Empedokles' myth

of the destiny of man. The banished god described by Hesiod is Man; all men are banished gods (Zuntz 267).

38

This is what we must bear in mind if we are to understand why the Orphic beliefs are significant for

Empedocles. His view of nature is by no means purely physical. It contains an element of eschatology such as

always accompanies the idea of a paradise lost or divine primal state (Jaeger 143).

14

influence, but the notion of achieving immortality is also present in Greek

mythology. Humans, Heroes, and Gods are considered to be a gradation of

progressively higher beings. Heroes such as Heracles, can, by overcoming a series of

obstacles, achieve divine status (Vernant 122).

Overall, starting from the religious point of view, Empedocles system is

characterized by a creative pantheism. The Sphere, Love, Strife, Harmony, the

Daimon are all semi-personified divine entities that inherently reflect mythical

characteristics.39 Love presides over every phase of creation by mixture. She models

and guides creation and is an omnipresent active force. Moreover, his theory of time

is essentially a mythical/religious one.40 The manifested universe is circumscribed in

cycles of creation and destruction with an oracular definiteness.

41,42

There is an

eschatology that involves human destiny in a return to a primal pure unity. 43

From the philosophical perspective, he uses common archaic conceptions

such as like is attracted to like, the correspondence between macrocosm and

microcosm,44 and a comprehensive theory of opposites, a common Presocratic

39

The Love and Strife of Empedocles and the Mind of Anaxagoras are cosmic powers, and they many be called

philosophic gods, though once more there is no suggestion that they should be worshipped or should oust the

popular divinities (Cornford 151).

40

In referring to the myth of recurrent cosmic cycles, Eliade observes: This myth was still discernibly present in

the earliest pre-Socratic speculations. Anaximander knows that all things are born and return to the apeiron.

Empedocles conceives of the alternate supremacy of the two opposing principles philia and neikos as explaining the

eternal creations and destructions of the cosmos (a cycle in which four phases are distinguishable, somewhat after

the fashion of the four incalculables of Buddhist doctrine). The universal conflagration is, as we have seen also

accepted by Heraclitus (Eliade 120).

41

The conception of the behaviour of the seasonal powers in the cycle of time is applied by Empedocles to the

strife of his four elements in the order of space: For all these are equal and coeval; but each has a different

prerogative (time) and its own character and ways (ethos can mean haunts, character, habits), and they prevail

in turn in the revolution in time.(Cornford 168).

42

In Empedocles, again, there appears the notion of a Great Year, in which worlds are generated and destroyed by

two alternating and opposite processes (Cornford 184).

43

It is precisely this parallel between the roles of Love and Strife in the two poems that constitutes the real link

between them, and the fundamental principle of unity in Empedocles thought. He seems to be insisting that the

same powers prevail in the destiny of the universe and in that of man. And just as the physical Sphere suggests a

supernatural harmony, so the element of Love in mortal compounds seems to stand as a physical representative for

the exiled daimon (Kahn 445).

44

For example, Primavesi points out the correspondence between the cyclical evolution of the universe and the

cycle of individual evolution: This means that in order to bring out the parallelism suggested by Empedocles, we

15

notion. He takes up the Eleatic problems the unity of being and posits an unlimited

notion of existence (Kirk, Raven, Schofield 288).

In terms of physics, his cosmological theories make use of certain mythic

structures. The primal unity of the sphere that is torn asunder by strife to begin

manifestation bears resemblance to the primal separation in cosmogonic schemes

(Kirk, Raven, Schofield 43). His speculation on primitive stages of evolution seem to

have mythical influences; whereas when dealing with the natural world and

physiological process, he is at his most materialistic and naturalistic. 45

Possibly one of the reasons why Empedocles is able to integrate mythical

notions into his natural system is that there is a certain valid structural consistency

to archaic mythological conceptions. Using a symbolic language, he is able to

replace anthropomorphic beings with natural forces because certain underlying

qualities of mythical concepts are maintained. According to Primavesi:

The obvious answer is that Empedocles is drawing on a method of decoding the

Homeric gods that had been current in the Greek West since the sixth century BCE:

according to this method, attested already for Theagenes of Rhegium, the Homeric

gods represent the basic entities of the physical universe, like elementary qualities

or the elements themselves. Thus, the traditional anthropomorphic design of these

gods is red-defined as a mere surface under which a deeper, physical level of

meaning has been hiding all the time. (Primavesi 257)

have to choose the Sphairos as a starting point on the physical side. We may say, then, that the rule of the Sphairos

corresponds to the happy state of the god within the community of the blessed ones, the destruction of the Sphairos

to his crime and departure, the movement towards complete separation to his punishment, and the movement toward

complete unity to this return (Primavesi 263).

45

The mythical law mirrors the physical theory in away that brings out its impact from a human perspective; it

shows the ethical implications of the physical theory by evaluating the different stages of the cosmic cycle.

Empedocles ethics is grounded in his physical theology as elucidated in the myth of the guilty god (Primavesi

269).

16

His system gives evidence of a dynamic interplay between muthos and

logos (or the mystical and the rational).46 Functioning on the principal of the creative

power of Love, he develops a paradoxical system of harmony by opposition where

muthos and logos, imagination and reason are not contradictory and mutually

exclusive.47 The dynamic interplay of Dionysian and Apollonian forces, so prevalent

in Greek thinking are integrated in a global system of dynamic harmony.

46

Regarding rationalist and mystic as contrasting and mutually exclusive terms, we are apt to classify our Greeks

as belonging to one or the other class - the Milesians on one side of the fence, the Orphics on the other, with a

disapproving frown for Empedocles because he insists on keeping one leg on each side. Surely what Empedocles

should teach us is that we are in a period of thought before such distinctions had any meaning. All shared a common

background which was neither rational nor mystical exclusively (Guthrie 103).

47

The relation between the two poems may therefore be compared wit that between logos and myth in Platonic

dialogues; with the important reservation that in Empedokles there is no definite distinction between these: are

Philia and Neikos myth, or not? (Zuntz 269)

17

Works Consulted

Adkins, Arthur W. H. ''Myth, Philosophy, and Religion in Ancient Greece.'' Myth and

Philosophy. Frank E. Reynolds & David Tracy, ed. Albany: SUNY Press, 1990. 95-130.

Print.

Bollack, Jean. Empedocle I. Introduction a lancienne physique. Paris : Les Editions

du Minuit, 1965. Print.

Bollack, Jean. ''Empedocles: Two Theologies, Two Projects.'' The Empedoclean

Kosmos: Structure, Process and the Question of Cyclity. Apostolis L. Pierris, ed.

Patras (Greece): Institute for Philosophical Research, 2005. 45-72. Print.

Boyanc, Pierre. Le culte des muses chez les philosophes grecs : tudes d'histoire

et de psychologie religieuse. Paris : de Boccard, 1936.

Burkert, Walter. ''Prehistory of Presocratic Philosophy in an Orientalizing Context.'' The

Oxford Handbook of Presocratic Philosophy. Patrica Curd & Graham D., eds. London:

Oxford University Press, 2008. 55-85. Print.

Cornford, F. M. Principium Sapientiae. Origins of Greek Philosophical Thought. New

York: Harper & Row, 1965. Print.

Curd, Patricia. ''On the Question of Religion and Natural Philosophy in Empedocles.''

The Empedoclean Kosmos: Structure, Process and the Question of Cyclicity.

Apostolis L. Pierris, ed. Patras (Greece): Institute for Philosophical Research,

2005. 137-162. Print.

Eliade, Mircea. Cosmos and History: The Myth of the Eternal Return. New York:

Harper and Row, 1954. Print.

Finkelberg, Aryeh. "On the Unity of Orphic and Milesian Thought." The Harvard

Theological Review 79. 4 (1986): 321-335 3 Apr. 2010

<http://www.jstor.org/stable/1509743>.

Freudenthal, Gad. "The Theory of the Opposites and an Ordered Universe: Physics

and Metaphysics in Anaximander." Phronesis 31. 3 (1986): 197-228 16 Oct.

2011

< http://www.jstor.org/stable/4182257 >.

Guthrie, W. K. C. " The Presocratic World-Picture." The Harvard Theological Review

45. 2 (1952): 87-104 18 Apr. 2010 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/1509743>.

Harris, Stephen L. & G. Platzner. Classical Mythology. Images and Insights. New York:

McGraw-Hill, 2004.

18

Hershbell, Jackson P. " Hesiod and Empedocles." The Classical Journal 65. 4 (1970):

145-161 3 Apr. 2010 < http://www.jstor.org/stable/3295548 >.

Hesiod & Theognis. Theogony, Works and Days, Elegies. London: Penguin Books,

1973. Print.

Inwood, Brad. The Poem of Empedocles. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001.

Print.

Jaeger, Werner. The Theology of the Early Greek Philosophers. London: Oxford

University Press, 1947. Print.

Kahn, Charles H. ''Religon and Natural Philosophy in Empedocles Doctrine of the Soul.''

The Pre-Socratics. Alexander P. D. Mourelatos, ed. New York: Anchor Books, 1974.

426-456.

Print.

Kingsley, Peter B. "Empedocles in the New Millenium." Classical Quarterly 22. 2

(2002): 333-413 3 Apr. 2010 < http://www.pdcnet.org/collection/show?

id=ancientphil_2002_0022_0002_0333_0414&file_type=xml&page=1>.

Kirk, G.S. Myth Its Meaning and Functions in Ancient and Other Cultures. London:

Cambridge University Press, 1970. Print.

Kirk, G.S. & J.E. Raven & M. Schofield. The Presocratic Philosophers. New York:

Cambridge University Press, 2009. Print.

Laks, Andr. "Between Religion and Philosophy: The Function of Allegory in the

Derveni Papyrus." Phronesis 42. 2 (1997): 121-142 3 Apr. 2010

<http://www.jstor.org/stable/4182551>.

Osborne, Catherine. ''Sin and Moral Responsibility in Empedocles Cosmic Cycle.''

The Empedoclean Kosmos: Structure, Process and the Question of Cyclity.

Apostolis L. Pierris, ed. Patras (Greece): Institute for Philosophical Research,

2005. 283-308. Print.

Pierris, Apostolis. ''Nature and Function of Love and Strife in the Empedoclean

System.'' The Empedoclean Kosmos: Structure, Process and the Question of

Cyclity. Apostolis L. Pierris, ed. Patras (Greece): Institute for Philosophical

Research, 2005. 190-224. Print.

Prier, Raymond Adolph. Archaic Logic: Symbol and Structure in Heraclitus,

Parmenides, and Empedocles. The Hague: Mouton & Co., 1976. Print.

Plutarch. Essays. London: Penguin Books, 1992. Print.

Primavesi, Oliver. ''Empedocles: Physical and Mythical Divinity.'' The Oxford Handbook

of Presocratic Philosophy. Patrica Curd & Graham D., eds. London: Oxford University

Press, 2008. 250-283. Print.

Proclus. Proclus' Commentary on Plato's Parmenides. Trans. Glenn R. Morrow and

John M. Dillon. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1987. Print.

19

Tate, Paul D. "Comparative Hermeneutics: Heidegger, the Pre-Socratics, and the

Rgveda" Philosophy East and West, 32. 1 (1982): 47-59 3 Apr. 2010

<http://www.jstor.org/stable/1398751>.

Trzaskoma, Stephen M., R, Scott Smith & S. Brunet, eds & transl. Anthology of

Classical Myth. Primary Sources in Translation. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing

Company, 2004.

Vernant, Jean. Mythe et pense chez les Grecs. Paris : ditions La Dcouverte, 1985.

Print.

West, M. L. Early Greek Philosophy and the Orient. Oxford: Oxford University Press,

1971. Print.

Zuntz, Gnther. Persephone. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971. Print.

The Bible Revised Standard Version. New York. American Bible Society. New York,

1971. Print.

The relationship between muthos and logos in the theogonies and cosmologies of

Ancient Greece range from the relatively straightforward mythos of

anthropormorphic gods of Homer and Hesiod to the rejection of muthos in favour of

strict logos adopted by Aristotle. Many comparative structuralist-oriented schools of

mythological theory have demonstrated the structural coherence of myths from a

symbolic perspective, be it from a social, psychological, or theological interpretation.

Examples range from Hesiods Theogony and Genesis to Pherekydes and Alcman as

well as the Orphic cosmogony from the Derveni papyrus. It could be considered that

there subsisted a basic world view generally adopted by most of the Presocratics

that reflected an established mythically-influenced world view. Furthermore, one can

notice a form of pantheism in the doctrines of the Milesians and Heraclitus, similar to

the pantheism found in Orphism. Conford posits three phases in the cosmogony of

Anaximander, common to Presocratic cosmogonies in general: (1) a primal Unity, a

state of indistinction or fusion in which factors that will later become distinct are

merged together. (2) out of this Unity emerge, by separation, pairs of opposite

things or powers; (3) this separating out leads to the disposition of the elemental

masses constituting the world-order, and the formation of the heavenly bodies. With

Empedocles, the qualities of a creative religious, mytho-poetic imagination fluent in

Homer, Hesiod, Pindar, and Parmenides allies itself with a rational mind keenly

interested in understanding the natural world. To analyze the relation of muthos and

logos in Empedocles system, samples from the fragments of his poems will be

examined covering such aspect as:The threefold conception of the Sphere/Harmony

Love Strife; Love as the force of unity of bringing things together, mixing the four

elements to form the universe; Apollo as divine mind; Zeus, Hera, Aidoneus and

Nestis as the four roots of all things; the role of opposites; the role of necessity; the

four generations in creation; the age of Cypris; Aphrodite as demiurge; eschatology

and divinisation.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- History and Practice of Magic by Paul Christian - SCAN For Art Collective - MAJOR TAROT Project 2014 OnwardDocument37 pagesHistory and Practice of Magic by Paul Christian - SCAN For Art Collective - MAJOR TAROT Project 2014 OnwardUncondemning Monk100% (2)

- TheeNetwork FlierDocument2 pagesTheeNetwork FlierUncondemning MonkPas encore d'évaluation

- THE FAMILY BYTES by Daniel O'DonnellDocument60 pagesTHE FAMILY BYTES by Daniel O'DonnellUncondemning MonkPas encore d'évaluation

- Dkmu - A History Lesion For Your Brain - OuchDocument3 pagesDkmu - A History Lesion For Your Brain - OuchUncondemning MonkPas encore d'évaluation

- Tags Tickets Customer #23661: Al Aguero 2 Tickets in Transaction# 36709, Printed Wednesday, April 09, 2014Document1 pageTags Tickets Customer #23661: Al Aguero 2 Tickets in Transaction# 36709, Printed Wednesday, April 09, 2014Uncondemning MonkPas encore d'évaluation

- Al Aguero HLA Hart PaperDocument8 pagesAl Aguero HLA Hart PaperUncondemning MonkPas encore d'évaluation

- Kafka and The Metamorphosis A 2nd or Alternate Proposal by Al AgueroDocument2 pagesKafka and The Metamorphosis A 2nd or Alternate Proposal by Al AgueroUncondemning MonkPas encore d'évaluation

- Pteryx Mapping SecretsDocument39 pagesPteryx Mapping SecretsUncondemning MonkPas encore d'évaluation

- COLI214B 04 Spring2014 BooklistAA2of2Document1 pageCOLI214B 04 Spring2014 BooklistAA2of2Uncondemning MonkPas encore d'évaluation

- The Most Outrageous U.S. Lies About Global HealthcareDocument46 pagesThe Most Outrageous U.S. Lies About Global HealthcareUncondemning MonkPas encore d'évaluation

- COLI Spring 2014 Syllabus AgueroDocument2 pagesCOLI Spring 2014 Syllabus AgueroUncondemning MonkPas encore d'évaluation

- ThevDojo Ov Thee Yippie Aiki Third Mind A Coyotel EssayDocument6 pagesThevDojo Ov Thee Yippie Aiki Third Mind A Coyotel EssayUncondemning MonkPas encore d'évaluation

- EU External Freedom of Expression PolicyDocument29 pagesEU External Freedom of Expression PolicyChristianTrahnelPas encore d'évaluation

- Medicine Buddha mantra advice from Lama Zopa RinpocheDocument3 pagesMedicine Buddha mantra advice from Lama Zopa Rinpochesumanenthiran123Pas encore d'évaluation

- On StupidityDocument21 pagesOn StupidityUncondemning MonkPas encore d'évaluation

- New Media Theories TimelineDocument1 pageNew Media Theories TimelineUncondemning Monk0% (1)

- Aisolve 2011 Visianal EnglishDocument4 pagesAisolve 2011 Visianal EnglishUncondemning MonkPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Will Judas Be in Heaven?Document11 pagesWill Judas Be in Heaven?akimelPas encore d'évaluation

- Sumerian Anunnaki GodsDocument23 pagesSumerian Anunnaki Godspablodarko8467% (3)

- Mythology of All Races Vol.3Document572 pagesMythology of All Races Vol.3davidcraig100% (5)

- Religion Spirituality Theology ComparisonDocument2 pagesReligion Spirituality Theology ComparisonEpay Castañares Lascuña100% (1)

- Restoration Activity Using Lego'sDocument9 pagesRestoration Activity Using Lego'sLynda Burton BlauPas encore d'évaluation

- 6 Indigenous PeopleDocument28 pages6 Indigenous PeopleJonathan Luke Mallari100% (1)

- The Fall of Man and God's Plan of Redemption (Actual Assignment)Document11 pagesThe Fall of Man and God's Plan of Redemption (Actual Assignment)Adrian Blake-WilliamsPas encore d'évaluation

- MATH119 Review 6Document4 pagesMATH119 Review 6Cassandra OctavianoPas encore d'évaluation

- Vedic MythologyDocument4 pagesVedic MythologyDaniel MonteiroPas encore d'évaluation

- FOI Homepage - Online Liturgy: Booklet: by Olivia RobertsonDocument5 pagesFOI Homepage - Online Liturgy: Booklet: by Olivia RobertsonskaluPas encore d'évaluation

- Jung, Carl Gustav - Volume 9 - The Archetypes of The Collective UnconsciousDocument26 pagesJung, Carl Gustav - Volume 9 - The Archetypes of The Collective UnconsciousDavid Alejandro Londoño60% (5)

- Akkadian Ex Eventu Prophecies.dDocument19 pagesAkkadian Ex Eventu Prophecies.dVlad BragaruPas encore d'évaluation

- Watchers NephilimDocument17 pagesWatchers Nephilimgeorgebuhay_666Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Paradox of Monotheism: Understanding the Esoteric FormDocument45 pagesThe Paradox of Monotheism: Understanding the Esoteric Formjena_01100% (3)

- Daniel Unlocks RevelationDocument114 pagesDaniel Unlocks Revelationmeko2100% (1)

- Psyche and EchoDocument6 pagesPsyche and EchoboasePas encore d'évaluation

- Midrash of Shemhazai and Azazel (Revised English)Document3 pagesMidrash of Shemhazai and Azazel (Revised English)Jeremy Kapp100% (6)

- How Many People Have Gone To Heaven?Document4 pagesHow Many People Have Gone To Heaven?jiadonisi100% (1)

- Paradise Lost - Course HeroDocument1 pageParadise Lost - Course HeroDaffodilPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson 9Document4 pagesLesson 9Winelfred G. PasambaPas encore d'évaluation

- Stories of Love and AdventureDocument8 pagesStories of Love and AdventureJohn Paul HolgadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Al Ma'thuratDocument33 pagesAl Ma'thuratGregoryMorse100% (1)

- Jesus Calling Bible Christmas Devotional - Week 4: ThankfulnessDocument18 pagesJesus Calling Bible Christmas Devotional - Week 4: ThankfulnessThomasNelsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture 03, 04,5 &6, 7history & Uloom Ul Quran-2Document64 pagesLecture 03, 04,5 &6, 7history & Uloom Ul Quran-2Ali WaqasPas encore d'évaluation

- Seth & The SeaDocument2 pagesSeth & The SeaMogg MorganPas encore d'évaluation

- Manual of Mythology - Greek, Roman, Norse, Hindu, German, & EgyptianDocument484 pagesManual of Mythology - Greek, Roman, Norse, Hindu, German, & EgyptianVan_Kiser100% (4)

- David Pack The Bible's Greatest PropheciesDocument288 pagesDavid Pack The Bible's Greatest Propheciesandrerox100% (1)

- Isis Is A Virgin MotherDocument27 pagesIsis Is A Virgin MotherKembaraLangit100% (1)

- Kenneth E Hagin - Bible Prayer Study CourseDocument290 pagesKenneth E Hagin - Bible Prayer Study CourseIdowu Olorunfemi Obanibi92% (12)

- 19 The Scriptures. New Testament. Hebrew-Greek-English Color Coded Interlinear: HebrewsDocument109 pages19 The Scriptures. New Testament. Hebrew-Greek-English Color Coded Interlinear: HebrewsMichaelPas encore d'évaluation