Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Hu Et Al, 2007 - Food Allergies (Qualitative Article) - ..

Transféré par

Obi DennarTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Hu Et Al, 2007 - Food Allergies (Qualitative Article) - ..

Transféré par

Obi DennarDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

771

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Parental food allergy information needs: a qualitative study

Wendy Hu, Carol Grbich, Andrew Kemp

...................................................................................................................................

Arch Dis Child 2007;92:771775. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.114975

See end of article for

authors affiliations

........................

Correspondence to:

Wendy Hu, Department of

Allergy, Immunology and

Infectious Diseases, The

Childrens Hospital at

Westmead, Locked Bag

4001, Westmead, NSW

2145, Australia;

wendyhu@med.usyd.edu.au

Accepted 20 April 2007

Published Online First

8 May 2007

........................

Objective: To examine information needs and preferences of parents regarding food allergy.

Design: Qualitative study including in-depth semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions. Data

were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and analysed using the constant comparative method, aided by

participant checking of interview summaries, independent reviewers and qualitative analysis software.

Participants: 84 parents of children with food allergy.

Setting: Three paediatric allergy clinics and a national consumer organisation.

Results: Most parent participants had received third level education (72%) and 39% had occupational

backgrounds in health and education. Parents experienced different phases in their need for information: at

diagnosis when there is an intense desire for information, at follow-up when there is continuing uncertainty

about allergy severity and appropriate management, and at new events and milestones. They preferred

information to be provided in a variety of formats, with access to reliable individualised advice between clinic

appointments, within the context of an ongoing relationship with a health professional. Parents wished to

know the reasoning behind doctors opinions and identified areas of core information content, including

unaddressed topics such as what to feed their child rather than what to avoid. Suboptimal information

provision was cited by parents as a key reason for seeking second opinions.

Conclusion: Parents with children with food allergies have unmet information needs. Study findings may assist

in the design and implementation of targeted educational strategies which better meet parental needs and

preferences.

he prevalence of food allergy appears to be increasing1 with

paediatricians consequently experiencing an increased

demand for specialist allergy services.2 It is widely agreed

in expert reviews and practice guidelines that comprehensive

parental advice and education is a cornerstone of food allergy

management.36 Limited parental knowledge has been documented in relation to using adrenaline autoinjectors712 and

reading food labels.13 Clinical audits have revealed suboptimal

levels of information provision1415 and that parents have a

number of common concerns regarding food allergy.2 However,

little is known about parental preferences for information

content and delivery, particularly given the complexity of the

strategies required to manage food allergy risk.16 Previous

research has demonstrated the value of qualitative methods in

ascertaining parental information needs concerning allergic

conditions such as atopic dermatitis and peanut avoidance in

pregnancy.17 18 This study examined the information needs and

preferences of parents with children with food allergies through

a multimethod qualitative approach.

METHODS

Families were recruited from three paediatric allergy clinics in

New South Wales (NSW), Australia. Together, these clinics

provide the bulk of such services in NSW, which has a

population of 6.7 million.19 In common with a worldwide

shortage of allergy services,20 families wait up to 6 months for

appointments at these clinics, where typically, 30 min is

allocated for initial medical consultations.

Families presenting with a child for evaluation of food allergy

were sampled purposively to include a range of allergy types

and severity, childrens ages and length of time since diagnosis.

Of 48 families invited to participate, four refused or were

excluded from involvement as it emerged that their child did

not have an allergy. Within a month of the clinic visit, in-depth

semi-structured interviews were audio-recorded with parents

concerning their childs food allergy, usual management

strategies, what they had learned from the clinic visit and

suggestions for improving information provision. Summaries of

these interviews were returned to parents for checking, with a

follow-up interview to ensure coverage of all key concerns. To

confirm and extend findings, four focus groups were held with

parents who were members of the consumer organisation

Anaphylaxis Australia Incorporated (AAI). AAI is the peak

Australian consumer body for food allergy and anaphylaxis

awareness, consumer support and education. All parent groups

who were invited agreed to participate, and all participants had

attended at least one of the three clinics. These discussions

covered similar topics to those in the interviews and were

audio-recorded. Following qualitative data collection, a brief

survey was administered to all parents regarding demographic

details, the childs food allergy characteristics and sources of

food allergy information.

All audio-recordings were transcribed verbatim and imported

into MAXqda2 (VERBI Software, Berlin, 2004) for analysis

using the constant comparative method.21 The data were read

repeatedly and codes developed from units of meaning as

expressed by participants. These codes were refined through

comparison between cases with contrasting and similar

attributes, such as stage of diagnosis. From these, thematic

categories were developed, from which data were systematically

coded. Sampling of families continued until theoretical saturation, or no new themes were found. To validate the thematic

categories, a selection of contrasting cases was independently

read by six expert reviewers from allergy and non-allergy

specialist, general practice, sociology, consumer and lay backgrounds. The study was approved by the human research ethics

committees at all three clinics and written informed consent

was obtained from all participants prior to interview.

RESULTS

A total of 84 parents drawn from 44 clinic recruited and 25

consumer organisation families participated. Tables 1 and 2 list

www.archdischild.com

772

Hu, Grbich, Kemp

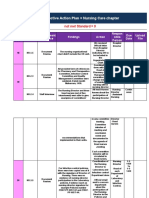

Table 1 Demographic details of parent participants

Age range

Average age

Third level education

Health or education occupation

Non-English speaking background*

23 to 55 years

37.9 years

72%

39%

27%

*Parents were asked which culture they identified with. Using standard

Australian Bureau of Statistics terminology, Australian was the most

commonly identified English-speaking background, and South European

the most commonly identified non-English-speaking background.

demographic features of the sample and characteristics of the

childs food allergy reported by parents. Most participants were

mothers (n = 69), with the remainder being fathers. Of the

clinic families, 22 were visiting the clinic for the first time and

22 for follow-up appointments, with the time since diagnosis

ranging from 0 to 8.5 years. Of all families, 39% (n = 27) had

sought second opinions regarding their childs food allergy.

Table 3 contains data extracts illustrating parental views on

information provision as described in the following sections.

Phases in information needs

Parents described three distinct phases in information seeking:

on initial diagnosis, at follow-up and at milestones. When food

allergy was first diagnosed, many parents described a period of

disbelief and distress concerning the severity of the allergy and

need for avoidance measures, accompanied by an intense desire

for information. Parents reported great variation in the amount

of take-home information provided by clinics, ranging from a

package containing many printed pages of written information,

illustrated booklets and videos at one clinic, to no information

at others. The majority of parents requested that more

information be given at the first visit, with only two parents

stating that they were given too much information.

At follow-up visits, parents who had lived with the diagnosis

for more than a year typically wished to know about their

childs current allergic status, recent scientific developments,

new food products and whether they were managing their

childs allergy with the appropriate level of concern and

vigilance. The latter was particularly important given persistent

uncertainty about the seriousness of their childs allergy,

especially for parents whose children had not experienced

anaphylaxis. Parents felt caught between the need to keep their

child safe from accidental allergen exposures but not overly

restrict their childs life and social opportunities.

Other information-seeking phases were those triggered by

the anticipation, or occurrence, of new events and milestones,

such as further acute reactions, starting childcare or school and

travel. These raised questions about precautionary strategies

such as educating teachers and carers, treatment procedures for

acute reactions and ensuring a safe food supply, particularly if

Table 2 Parent-reported characteristics of childs food

allergy

Age range of allergic child

Average age of allergic child

More than one food allergy

Peanut or tree nut allergy

Previous anaphylaxis*

Have autoinjector

0.6 to 15.2 years

5.1 years

59%

76%

42%

77%

*This was defined in the survey as An anaphylactic reaction is the most

serious type of allergic reaction. The person can have trouble breathing,

swelling of their tongue or throat, difficulty talking or a hoarse voice, noisy

breathing, wheeze or persistent cough, loss of consciousness or collapse, or

go pale and floppy, and is taken from parent education materials

34

developed by the Australian professional body for allergists.

www.archdischild.com

the parent could not be present and had to entrust the care of

their child to another.

Information content needs

Parents described needs regarding two aspects of information

content. The first concerned the reasoning behind the doctors

judgments about their childs allergy, including the likelihood

of anaphylaxis, and the recommended management. When

parents did not understand the basis of the doctors opinion,

they would continue to speculate after the consultation, for

example by presuming that the size of the skin test correlated

with the risk of anaphylaxis and requirement for an autoinjector.

The second type of information concerned basic medical facts

and practical advice related to daily management. These core

areas, as identified by parents, are listed in table 4. These needs

clearly persisted after the clinic visit, with the interview

triggering queries about topics such as techniques for using

the autoinjector, the meaning of skin test results and the need

for follow-up visits. Most of all, parents whose children had

significant food allergies talked at length about needing

information regarding what they should feed their child, as

distinct from what they should avoid. Dietary management was

one of the most life-changing aspects of food allergy and there

was continual concern over the effect of restrictive diets on the

childs nutritional status and growth. There was also considerable confusion over the extent to which parents should exclude

allergens from the childs diet and environment. Examples

included whether foods labelled may contain traces should

be avoided, or whether all foods from a group (eg, tree nuts),

should be avoided if there was an allergy to one food (eg,

peanut). A minority (n = 6, 27%) of newly diagnosed families

had been referred to a dietician.

Table 3 Data extracts concerning parental information

needs and preferences

Just naturally [as parents], I think we crave information, especially when its

something that affects your children, and theres not much other

information out there, your doctors pretty much, the primary source. And

you need to get the answers from them, because if you dont, then you risk,

you know, trying to search the internet, getting information from current

affairs programs, where its not always relevant to your situation. And you

can start making assumptions, and getting carried away, and getting

worried about things that you dont need to be worried about. Tess (mother,

clinic recruited)*

Initially, nobody actually starts with, what is anaphylaxis? Because well, for

me, I mean, Id never heard of it. Ive no medical background, I had no idea

what they were talking about. Lori (mother, consumer organisation)

And just nobody ever really explained that. [] Ive been involved with my

sons allergy for over two years, and I have never understood any of this.

and as I came home from that [nurse education session] I said to my

partner.in a sense I felt like a real weight had been lifted? Because when

you understand something you feel like you have a little bit of control over it.

Sabrina (mother, clinic recruited)

Its a sort of a stressful time, when youre up there, with a child, particularly

when theyre young because theyre jumping around the room, and

theyre either tired, because its their sleep time, or whatever it may be. And

its very hard to try to remember all your questions, concentrate on what

theyre saying, concentrate on keeping your child quiet, so you can hear

[laugh]. Melinda (mother, clinic recruited)

Yeah, its really reassuring when [the doctor] comes along and says, I dont

think you should have that. [] We dont know how much weve worried

and panicked over things or not thats the thing. But when the specialist

worries with you, you go, good, were not being over-anxious here. Robyn

(mother, clinic recruited)

*Pseudonyms are used for all participants.

Parental food allergy information needs

773

Table 4 Core information needs identified by parents

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

What is anaphylaxis? What is not anaphylaxis?

Recognising symptoms of allergic reactions, the timescale of reactions.

How accidental exposures occur and how to manage risky situations.

What to feed your child (rather than what to avoid), maintenance of nutrition.

Practical allergen avoidance: label reading, shopping, cooking, social events, eating out and travel. How to find allergen-free products.

When and how to give the autoinjector. Revision of techniques at each visit.

How to educate extended family, other carers and adults who may give the child food.

Risks and benefits of skin testing and oral challenges. Interpretation of results.

When follow-up is required, and why.

Where more information may be found, eg nurse-led education sessions, consumer organisations, contacting the clinic.

How to educate your child.

Background information about allergy, the relationship between asthma, eczema and food allergy, natural history of food allergy.

Preferences for information delivery

Three key aspects were described in relation to information

delivery. The first concerned clinic procedures and accessibility.

Clinic visits were often prolonged by multiple encounters,

including initial allergist consultation, skin testing with a

technician, and the allergist again, sometimes with the addition

of dietician and nurse-led education, a process that lasted some

hours. As a result, when final opinions and advice were

presented by the allergist, parents were often distracted by a

tired and bored child. Parents also consistently requested a

method through which they could have their queries addressed

between clinic appointments, preferably by a health professional familiar with their case.

A second aspect related to information formats. Written takehome information was strongly preferred, as it was difficult to

recall details about food ingredients and products, but not as a

substitute for talking with a health professional. Parents also

spoke highly of videos, which they found essential for

educating their child, extended family, child care workers and

teachers. A desire for more information led many parents to

search the internet, which 73 (87%) parents reported using as a

source of food allergy information. However, they questioned

its reliability, preferring to receive more trustworthy information from their doctor. Parents who had been referred to nurseled education sessions consistently found them valuable,

particularly if they had time to formulate questions between

the consultation and the session, and have them answered.

However, only a minority (9.8%) of clinic parents had been

referred to and attended such sessions.

The third and most important aspect was the doctorparent

child relationship. The most common reasons for seeking a

second opinion were insufficient information provision, difficulty having questions answered, advice that was perceived to

be either too restrictive or too cavalier, and non-acknowledgement of the child as the patient. Parents noted that doctors

who provided more information would readily answer their

questions and spent more time with them. What parents valued

was consistent information given in the context of a long-term

partnership that acknowledged their uncertainties and concerns.

DISCUSSION

This study has shown that parents with children with food

allergies have unmet information needs which continue after

clinic visits. In common with other qualitative studies

concerning parental experiences with allergic conditions,17 18

the study has found persistent uncertainties concerning the

daily management of allergies. There are also similarities with

findings from interview studies conducted with parents of

children with non-allergic long-term conditions, where participants preferred information provision to be part of a trusting

and ongoing relationship with health professionals.22 23 Our

findings, however, are new in relation to families with children

with food allergies. They document how information needs

may change over time, and include parental preferences

concerning the content, format and delivery of information.

Although the use of multiple data collection methods has

enhanced internal validity, our findings are of unknown

generalisability as the study was conducted in specific settings

with a selected population. Notably, the parents high level of

third level education, and occupational backgrounds in health

and education, including nursing, medicine, psychology and

childcare, may have influenced information preferences. These

may not reflect the information needs of all parents, and less

well educated parents may have differing needs which should

also be addressed. Educational levels, however, were comparable to the 70.9% of the NSW population of this age range with

third level education24 and it is possible that the occupational

backgrounds of parents in the study are typical of families who

seek specialist help for childhood food allergies. The low rate of

refusal and theoretical saturation suggests that the sample

covered the range of parental experiences in the clinic

population. The inclusion of consumer organisation members

may have also skewed results towards a preference for greater

information provision, as patients tend to seek out health

consumer organisations to find more information.25 However,

in this study, clinic-recruited parents whose children had

significant allergies also consistently requested more information; the difference was that consumer organisation parents

had dealt with food allergy for some time and were better able

to describe the specific information that parents required.

Consumer organisation representatives may also be best placed

to understand the intricacies of food allergy daily management.16

Our findings suggest ways in which information provision

may be optimised. It appears that information content tailored

to parental needs at specific times is preferred, and models for

health information seeking support this contention.26 For

example, at diagnosis, the list of core information could be

used as a checklist for discussion and written materials.

However, the complexity and amount of education required

suggests that even core information will be difficult to convey

within one consultation. This implies a need to ensure followup, for example to check parental understanding of dietary

advice or skin prick test results, and in particular that a strongly

positive result correlates only with the likelihood of allergy and

not with the severity of subsequent reactions.27

Given shortages of specialist services,20 alternative methods

of information provision that do not necessarily increase the

requirement for doctors time may need to be found. Written

information is important but requires explanation and review

to ensure parental understanding.28 Our findings suggest that

alternative formats such as video, may have more impact. As

only a minority of clinic-recruited families were referred to a

www.archdischild.com

774

Hu, Grbich, Kemp

What is already known on this topic

N

N

Comprehensive advice and education is required in

order to safely manage food allergy.

Parents have limited recall and knowledge about food

labelling and use of adrenaline autoinjectors, but little is

known about their preferences for information provision.

in a variety of formats, and in an accessible, ongoing, parent

and child-centred manner. Knowledge of parental preferences

may enable clinicians to better fulfil information needs and

findings from this study may assist in the development of more

effective educational strategies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to gratefully acknowledge Anaphylaxis Australia

Incorporated (AAI) for their assistance with this study.

.......................

Authors affiliations

What this study adds

N

N

Many parents experience persistent uncertainty regarding the appropriate balance between keeping their child

safe from accidental allergen exposures and not restricting their childs growth, nutritional status and social

development.

Important content areas for information provision include

what to feed the food allergic child, rather than what to

avoid, and the basis for doctors judgements concerning

the childs risk of anaphylaxis.

Andrew Kemp, Department of Allergy, Immunology and Infectious

Diseases, The Childrens Hospital at Westmead, New South Wales,

Australia

Wendy Hu, Discipline of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of

Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Carol Grbich, School of Medicine, Flinders University, South Australia,

Australia

Funding: WH was supported by the Australian Allergy Foundation and the

National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia, ID

no. 297112. Neither funding body had any role in the study design,

collection and analysis of data, or in the writing and submission of this

manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

REFERENCES

dietician or nurse-led education session, greater utilisation of

these services may better meet information needs. Previous

studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of multidisciplinary approaches in improving parental knowledge.29 30 Given the

proportion of parents who access the internet for health

information both in this study and more generally,31 it could

be better utilised by providing guidance to trustworthy

websites. For example, a trained allergy nurse could use email

to answer queries and provide reliable individualised information between clinic visits. Streamlining clinic procedures and

suggesting that parents attend with another adult for childminding may reduce parental distraction by children and

improve the effectiveness of doctorparent communication.

Our study findings also suggest that the rate of second opinion

seeking may be reduced by better meeting parental information

preferences and by addressing discrepancies between parental

and allergist views of the risks. The latter are known to differ,32

supporting parental preferences for doctors to explain the

reasoning behind their opinions. Longitudinal studies of clinic

populations have had differing results concerning the effectiveness of parent education. One study found that parental

education at the time of autoinjector prescription was followed

by use of the device in only 29% of anaphylactic reactions.7

Another study found that detailed advice, written information

and regular follow-up was associated with a reduction in the

severity and frequency of acute reactions to food in children.33 An

explanation for these discrepancies, as suggested by this study, is

that it is not only the quantity and quality of information

provision, but also the extent to which it matches parental needs,

which will determine its effect.

CONCLUSIONS

The information needs of parents with children with food

allergies vary over time but parents consistently request more

information provision from their specialist. This has resource

implications, but these may be minimised through alternative

strategies to provide information. More time spent initially or

through more frequent follow-up consultations may also

compensate for an even greater use of resources if second

opinions are sought. Parents prefer information to be delivered

www.archdischild.com

1 Warner JO. Peanut allergy: a major public health issue. Pediatr Allergy Immunol

1999;10(1):1420.

2 Rosenthal M. How a non-allergist survives an allergy clinic. Arch Dis Child

2003;89:23843.

3 Simons FE. Anaphylaxis, killer allergy: long-term management in the community.

J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006;117(2):36777.

4 Ewan PW, Clark AT. Long-term prospective observational study of patients with

peanut and nut allergy after participation in a management plan. Lancet

2001;357(9250):11115.

5 Sampson H. Food allergy. Part 2: diagnosis and management. J Allergy Clin

Immunol 1999;103(6):9819.

6 American Academy of Asthma, Allergy and Immunology. Food allergy: a

practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2006;96(3 Suppl 2):S168.

7 Gold MS, Sainsbury R. First aid anaphylaxis management in children who were

prescribed an epinephrine autoinjector device (EpiPen). J Allergy Clin Immunol

2000;106(1 Pt 1):1716.

8 Sicherer SH, Forman JA, Noone SA. Use assessment of self-administered epinephrine

among food-allergic children and pediatricians. Pediatrics 2000;105(2):35962.

9 Huang SW. A survey of Epi-PEN use in patients with a history of anaphylaxis.

J Allergy Clin Immunol 1998;102(3):5256.

10 Pouessel G, Deschildre A, Castelain C, et al. Parental knowledge and use of

epinephrine auto-injector for children with food allergy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol

2006;17(3):2216.

11 Arkwright PD, Farragher AJ. Factors determining the ability of parents to

effectively administer intramuscular adrenaline to food allergic children. Pediatr

Allergy Immunol 2006;17(3):2279.

12 Kim JS, Sinacore JM, Pongracic JA. Parental use of EpiPen for children with food

allergies. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005;116(1):1648.

13 Joshi P, Mofidi S, Sicherer SH. Interpretation of commercial food ingredient

labels by patients of food-allergic children. J Allergy Clin Immunol

2002;109(6):101921.

14 Ratnaweera D, von Trilsbach J, Rangasami J, et al. Audit of nurse-led training for

EpiPen in a district general hospital. Allergy 2006;61(8):101920.

15 Clegg S, Ritche J. EpiPen training: a survey of the provision for parents and

teachers in West Lothian. Ambulatory Child Health 2001;7:16975.

16 Munoz-Furlong A. Daily coping strategies for patients and their families.

Pediatrics 2003;111(6 Pt 3):165461.

17 Turke J, Venter C, Dean T. Maternal experiences of peanut avoidance during

pregnancy/lactation: an in-depth qualitative study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol

2005;16(6):51218.

18 Gore C, Johnson RJ, Caress AL, et al. The information needs and preferred roles

in treatment decision-making of parents caring for infants with atopic dermatitis:

a qualitative study. Allergy 2005;60(7):93843.

19 Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2001 Census Community Profile: New South

Wales. Expanded Community Profile. Issued 19 Nov 2002. Available from

www.abs.gov.au (accessed 19 May 2004).

20 Warner JO, Kaliner MA, Crisci CD, et al. Allergy practice worldwide: a report by

the World Allergy Organization Specialty and Training Council. Int Arch Allergy

Immunol 2006;139(2):16674.

21 Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative

research. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1967.

22 Nuttila K, Salantera S. Children with long-term illness: parents experiences of

care. J Pediatr Nurs 2006;21(2):15360.

Parental food allergy information needs

23 Garwick AW, Patterson JM, Bennett FC, et al. Parents perception of helpful vs.

unhelpful types of support in managing the care of preadolescents with chronic

conditions. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1998;152(7):66571.

24 Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2001 Census Community Profile Series: Sydney

(Statistical Division). Basic Community Profile. Available from www.abs.gov.au

(accessed 22 May 2007).

25 Allsop J, Jones K, Baggott R. Health consumer groups in the UK: a new social

movement? Sociol Health Illn 2004;26(6):73756.

26 Longo DR. Understanding health information, communication and information

seeking of patients and consumers: a comprehensive and integrated model.

Health Expect 2005;8(3):18994.

27 Clark AT, Ewan PW. Interpretation of tests for nut allergy in one thousand

patients, in relation to allergy or tolerance. Clin Exp Allergy

2003;33(8):10415.

28 Berry D. Risk communication and health psychology. Berkshire, UK: Open

University Press, 2004.

775

29 Kapoor S, Roberts G, Bynoe Y, et al. Influence of a multidisciplinary paediatric

allergy clinic on parental knowledge and the rate of subsequent allergic

reactions. Allergy 2004;59(2):18591.

30 Vickers DW, Maynard L, Ewan PW. Management of children with potential

anaphylactic reactions in the community: a training package and proposal for

good practice. Clin Exp Allergy 1997;27(8):898903.

31 Wainstein BK, Sterling-Levis K, Baker SA, et al. Use of the internet by parents of

paediatric patients. J Pediatr Child Health 2006;42(9):52832.

32 Hourihane JO. Are the dangers of childhood food allergy exaggerated? BMJ

2006;333(7566):4968.

33 Ewan PW, Clark AT. Efficacy of a management plan based on severity

assessment in a longitudinal and case-controlled studies of 747 children with nut

allergy: proposal for good practice. Clin Exp Allergy 2005;35(6):7516.

34 Australasian Society for Clinical Immunology and Allergy. Guidelines for

EpiPen prescription. Available from www.allergy.org.au (accessed 22 May

2007).

BMJ Clinical EvidenceCall for contributors

BMJ Clinical Evidence is a continuously updated evidence-based journal available worldwide on

the internet which publishes commissioned systematic reviews. BMJ Clinical Evidence needs to

recruit new contributors. Contributors are healthcare professionals or epidemiologists with

experience in evidence-based medicine, with the ability to write in a concise and structured way

and relevant clinical expertise.

Areas for which we are currently seeking contributors:

Secondary prevention of ischaemic cardiac events

Acute myocardial infarction

MRSA (treatment)

Bacterial conjunctivitis

However, we are always looking for contributors, so do not let this list discourage you.

N

N

N

N

Being a contributor involves:

Selecting from a validated, screened search (performed by in-house Information Specialists)

valid studies for inclusion.

Documenting your decisions about which studies to include on an inclusion and exclusion form,

which we will publish.

Writing the text to a highly structured template (about 15003000 words), using evidence from

the final studies chosen, within 810 weeks of receiving the literature search.

Working with BMJ Clinical Evidence editors to ensure that the final text meets quality and style

standards.

Updating the text every 12 months using any new, sound evidence that becomes available. The

BMJ Clinical Evidence in-house team will conduct the searches for contributors; your task is to

filter out high quality studies and incorporate them into the existing text.

To expand the review to include a new question about once every 12 months.

In return, contributors will see their work published in a highly-rewarded peer-reviewed

international medical journal. They also receive a small honorarium for their efforts.

If you would like to become a contributor for BMJ Clinical Evidence or require more information

about what this involves please send your contact details and a copy of your CV, clearly stating the

clinical area you are interested in, to CECommissioning@bmjgroup.com.

N

N

N

N

N

N

Call for peer reviewers

BMJ Clinical Evidence also needs to recruit new peer reviewers specifically with an interest in the

clinical areas stated above, and also others related to general practice. Peer reviewers are

healthcare professionals or epidemiologists with experience in evidence-based medicine. As a

peer reviewer you would be asked for your views on the clinical relevance, validity and

accessibility of specific reviews within the journal, and their usefulness to the intended audience

(international generalists and healthcare professionals, possibly with limited statistical knowledge).

Reviews are usually 15003000 words in length and we would ask you to review between 25

systematic reviews per year. The peer review process takes place throughout the year, and our

turnaround time for each review is 1014 days. In return peer reviewers receive free access to

BMJ Clinical Evidence for 3 months for each review.

If you are interested in becoming a peer reviewer for BMJ Clinical Evidence, please complete the

peer review questionnaire at www.clinicalevidence.com/ceweb/contribute/peerreviewer.jsp

www.archdischild.com

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Children's Eating Behavior InventoryDocument14 pagesThe Children's Eating Behavior Inventoryguilherme augusto paroPas encore d'évaluation

- The Birth of Black Power in BritainDocument24 pagesThe Birth of Black Power in BritainObi DennarPas encore d'évaluation

- OBGYN History GuideDocument4 pagesOBGYN History GuideMaruti100% (3)

- Hazard Prevention Through Effective Safety and Health Training - Table - ContentsDocument1 pageHazard Prevention Through Effective Safety and Health Training - Table - ContentsAmeenudeen0% (1)

- NCP DRDocument3 pagesNCP DRRhuwelyn Parantar PilapilPas encore d'évaluation

- Art.03 de 2do CasoDocument10 pagesArt.03 de 2do CasokristexPas encore d'évaluation

- 582 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR: Food Allergy Associated with Reduced Access to CareDocument9 pages582 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR: Food Allergy Associated with Reduced Access to CarewilmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Biostatistics ResearchDocument35 pagesBiostatistics ResearchChristopher SorianoPas encore d'évaluation

- Evaluating A Handbook For Parents of Children With Food Allergy: A Randomized Clinical TrialDocument8 pagesEvaluating A Handbook For Parents of Children With Food Allergy: A Randomized Clinical Trialbrakim23Pas encore d'évaluation

- Clinical and Experimental AllergyDocument10 pagesClinical and Experimental AllergyxXluisPas encore d'évaluation

- ResearchintegrativereviewDocument17 pagesResearchintegrativereviewapi-315402591Pas encore d'évaluation

- Key Assessment #2 Research ProspectusDocument9 pagesKey Assessment #2 Research Prospectusrachael costelloPas encore d'évaluation

- By Guest On July 22, 2019 Downloaded FromDocument3 pagesBy Guest On July 22, 2019 Downloaded FromNoviaPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Paper On AllergiesDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On Allergiesc9snjtdx100% (3)

- EvidencebasedpracticepedsresearchpaperDocument6 pagesEvidencebasedpracticepedsresearchpaperapi-278552800Pas encore d'évaluation

- European study explores influences on infant feeding decisionsDocument6 pagesEuropean study explores influences on infant feeding decisionsPoppyPas encore d'évaluation

- Pediatric Dentistry Aom Pacifier 2001Document5 pagesPediatric Dentistry Aom Pacifier 2001Kobayashi MaruPas encore d'évaluation

- Research ProposalDocument4 pagesResearch ProposalAmar GandhiPas encore d'évaluation

- Infant Feeding Practices and Reported Food Allergies at 6 Years of AgeDocument10 pagesInfant Feeding Practices and Reported Food Allergies at 6 Years of AgeLia ApriliaPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Article: Feeding Bottles Usage and The Prevalence of Childhood Allergy and AsthmaDocument9 pagesResearch Article: Feeding Bottles Usage and The Prevalence of Childhood Allergy and AsthmaMuhammad Bayu Zohari HutagalungPas encore d'évaluation

- Alergias y Diversidad Alimentaria 2014Document16 pagesAlergias y Diversidad Alimentaria 2014Genesis VelizPas encore d'évaluation

- Growth Comparison in Children With and Without Food Allergies in 2 Different Demographic PopulationsDocument7 pagesGrowth Comparison in Children With and Without Food Allergies in 2 Different Demographic PopulationsMaria Agustina Sulistyo WulandariPas encore d'évaluation

- Peds 2009-1210v1Document9 pagesPeds 2009-1210v1ahmed shawkyPas encore d'évaluation

- A Comparision of Eating Behaviors Between Children With and Without Autism (2016)Document7 pagesA Comparision of Eating Behaviors Between Children With and Without Autism (2016)evellynPas encore d'évaluation

- A Comparison of Eating Behaviors Between Children With and Without AutismDocument7 pagesA Comparison of Eating Behaviors Between Children With and Without AutismbarbaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Article 1Document10 pagesArticle 1nishaniindunilpeduruhewaPas encore d'évaluation

- A Comparison of Eating Behaviors Between Children With and Without AutismDocument7 pagesA Comparison of Eating Behaviors Between Children With and Without AutismluluPas encore d'évaluation

- PediatricsDocument10 pagesPediatricsapi-253312159Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pediatrics 2012 Dilley S7 8Document4 pagesPediatrics 2012 Dilley S7 8Elis Sri AlawiyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Hoyos Bachiloglu2014Document6 pagesHoyos Bachiloglu2014Crhistian Toribio DionicioPas encore d'évaluation

- Pediatrics 2013 Davis S5Document3 pagesPediatrics 2013 Davis S5phobicmdPas encore d'évaluation

- Nutritional Neuroscience and Education5Document14 pagesNutritional Neuroscience and Education5Ingrid DíazPas encore d'évaluation

- Food SecurityDocument16 pagesFood Securityno facePas encore d'évaluation

- The Children Eating Behavior Inventory CebiDocument15 pagesThe Children Eating Behavior Inventory CebiNina SalinasPas encore d'évaluation

- Kcanales Annotated Bib FinalDocument7 pagesKcanales Annotated Bib Finalapi-242275715Pas encore d'évaluation

- Food Allergy Risks Higher for Children, Males, BlacksDocument3 pagesFood Allergy Risks Higher for Children, Males, BlackssupermaneditPas encore d'évaluation

- Pediatric Food Allergy: A Clinical GuideD'EverandPediatric Food Allergy: A Clinical GuideRuchi S. GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Factors Influencing Malnutrition Among Under Five Children at Kitwe Teaching Hospital, ZambiaDocument10 pagesFactors Influencing Malnutrition Among Under Five Children at Kitwe Teaching Hospital, ZambiaInternational Journal of Current Innovations in Advanced Research100% (1)

- Breastfeeding and Parafunctional Oral Habits in Children With and Without Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity DisorderDocument7 pagesBreastfeeding and Parafunctional Oral Habits in Children With and Without Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity DisorderCloudcynaraaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2011 NIAIDSponsored 2010 Guidelines For Managing Food Allergy Applications in The Pediatric PopulationDocument13 pages2011 NIAIDSponsored 2010 Guidelines For Managing Food Allergy Applications in The Pediatric PopulationLily ChandraPas encore d'évaluation

- Child Eating Behaviors and Caregiver Feeding Practices in Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersDocument10 pagesChild Eating Behaviors and Caregiver Feeding Practices in Children With Autism Spectrum DisorderspedroPas encore d'évaluation

- Clinical Nutrition: Feeding Difficulties in Children With Inherited Metabolic Disorders: A Pilot StudyDocument9 pagesClinical Nutrition: Feeding Difficulties in Children With Inherited Metabolic Disorders: A Pilot StudyGita Fajar WardhaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Qualitative Analysis Vaccinated ParentsDocument20 pagesQualitative Analysis Vaccinated Parentsjackbane69Pas encore d'évaluation

- Preferences and Growth How Do Toddler EaDocument9 pagesPreferences and Growth How Do Toddler EaFonoaudiólogaRancaguaPas encore d'évaluation

- Effectiveness of Nebulizer Use-Targeted Asthma Education On Underserved Children With Asthma - PMCDocument18 pagesEffectiveness of Nebulizer Use-Targeted Asthma Education On Underserved Children With Asthma - PMCPatricia LPas encore d'évaluation

- Integrative Literature Review - HolowaychukDocument16 pagesIntegrative Literature Review - Holowaychukapi-432212585Pas encore d'évaluation

- Managing asthma and allergies in school settingsDocument4 pagesManaging asthma and allergies in school settingsinggrit06Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pediatrics 2013 Feuille S7 8Document4 pagesPediatrics 2013 Feuille S7 8yuliantiumurahPas encore d'évaluation

- Lay Prevalence Paper FinalDocument5 pagesLay Prevalence Paper Final강동희Pas encore d'évaluation

- Knowledge and attitudes towards baby-led weaningDocument7 pagesKnowledge and attitudes towards baby-led weaningmyjesa07Pas encore d'évaluation

- Allergies Amoung Tactile Defensive Children: Current Allergy and Clinical Immunology May 2004Document4 pagesAllergies Amoung Tactile Defensive Children: Current Allergy and Clinical Immunology May 2004Jody ThiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Breastfeeding Duration and Early Parenting Behaviour The Importance of An Infant-Led, Responsive StyleDocument7 pagesBreastfeeding Duration and Early Parenting Behaviour The Importance of An Infant-Led, Responsive Styleadri90Pas encore d'évaluation

- Literature Review On AllergyDocument8 pagesLiterature Review On Allergyogisxnbnd100% (1)

- Effect of Television Food Advertisement On Children's Food Purchasing RequestsDocument8 pagesEffect of Television Food Advertisement On Children's Food Purchasing RequestsImran RafiqPas encore d'évaluation

- Association of Household Food Security Status PDFDocument9 pagesAssociation of Household Food Security Status PDFArvin James PujanesPas encore d'évaluation

- Association PDFDocument4 pagesAssociation PDFLia RusmanPas encore d'évaluation

- A Comparison of Eating Behaviors Between Children With and Without AutismDocument6 pagesA Comparison of Eating Behaviors Between Children With and Without Autismguilherme augusto paroPas encore d'évaluation

- Food AlergyDocument11 pagesFood AlergyAhmad HafizyPas encore d'évaluation

- Vitamin D Insufficiency Is Associated With Challenge-Proven Food Allergy in InfantsDocument14 pagesVitamin D Insufficiency Is Associated With Challenge-Proven Food Allergy in InfantswilmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Food Insecurity Linked to Obesity in Homes With KidsDocument5 pagesFood Insecurity Linked to Obesity in Homes With KidsdetailsPas encore d'évaluation

- Food Allergies: a Recipe for Success at School: Information, Recommendations and Inspiration for Families and School PersonnelD'EverandFood Allergies: a Recipe for Success at School: Information, Recommendations and Inspiration for Families and School PersonnelPas encore d'évaluation

- Level of Awareness of Post Partum Mothers On Newborn Screening EssaysDocument4 pagesLevel of Awareness of Post Partum Mothers On Newborn Screening EssaysJig GamoloPas encore d'évaluation

- Additives and PreservativesDocument3 pagesAdditives and Preservativesbellydanceafrica9540Pas encore d'évaluation

- Neu 2014Document7 pagesNeu 2014Hải TrầnPas encore d'évaluation

- 12345Document12 pages12345Obi DennarPas encore d'évaluation

- 12345Document4 pages12345Obi DennarPas encore d'évaluation

- I Choose Exile Richard WrightDocument5 pagesI Choose Exile Richard WrightObi DennarPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 67T'ShakaDocument20 pages5 67T'ShakaObi Dennar100% (2)

- Chapter Five TermsDocument2 pagesChapter Five TermsObi DennarPas encore d'évaluation

- 1765 and 1788 SwagDocument3 pages1765 and 1788 SwagObi DennarPas encore d'évaluation

- Historical Presentations in SchoolDocument1 pageHistorical Presentations in SchoolObi DennarPas encore d'évaluation

- An Impression Technique For Patients With Fixed Orthodontic AppliancesDocument2 pagesAn Impression Technique For Patients With Fixed Orthodontic Appliancesmoji_puiPas encore d'évaluation

- Airway Clearance Physiology Pharmacology Techniques and Practice PDFDocument5 pagesAirway Clearance Physiology Pharmacology Techniques and Practice PDFPaoly PalmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippine Medical Technology: Education & Career GuideDocument64 pagesPhilippine Medical Technology: Education & Career GuideLovely Reianne ManigbasPas encore d'évaluation

- Medigroup Proposal For ICU BedsDocument13 pagesMedigroup Proposal For ICU Bedsmohyeb padamshiPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal Keperawatan Muhammadiyah: Pelangi Jiwa Aobama, Dedy PurwitoDocument11 pagesJurnal Keperawatan Muhammadiyah: Pelangi Jiwa Aobama, Dedy PurwitoVania Petrina CalistaPas encore d'évaluation

- Advanced Practice Nursing PhilosophyDocument10 pagesAdvanced Practice Nursing Philosophyfmiller001Pas encore d'évaluation

- PE and Health: Quarter 2 Module 8 Organizing A Dance EventDocument6 pagesPE and Health: Quarter 2 Module 8 Organizing A Dance EventMary Joy Cejalbo100% (1)

- IDSR Technical Guidelines 2nd Edition - 2010 - English PDFDocument416 pagesIDSR Technical Guidelines 2nd Edition - 2010 - English PDFChikezie OnwukwePas encore d'évaluation

- Priyanshu - Sarkar - Project Report On Internship ProgramDocument25 pagesPriyanshu - Sarkar - Project Report On Internship ProgramLog InPas encore d'évaluation

- OGDocument385 pagesOGMin MawPas encore d'évaluation

- Routine Episiotomy For Vaginal Birth: Should It Be Ignored?Document8 pagesRoutine Episiotomy For Vaginal Birth: Should It Be Ignored?IOSRjournalPas encore d'évaluation

- Tabel Penetapan Prioritas 5 ILMDocument12 pagesTabel Penetapan Prioritas 5 ILMyantiPas encore d'évaluation

- Effective Messages in Vaccine Promotion: A Randomized Trial: PEDIATRICS March 2014Document11 pagesEffective Messages in Vaccine Promotion: A Randomized Trial: PEDIATRICS March 2014Kroof KayPas encore d'évaluation

- Cervical Checks in Labor ExplainedDocument17 pagesCervical Checks in Labor ExplainedClaire Anne PunsalanPas encore d'évaluation

- Caries TimelineDocument11 pagesCaries TimelineManuelRomeroFPas encore d'évaluation

- Cbahi Esr StandardDocument7 pagesCbahi Esr StandardSitti Frizaida AininPas encore d'évaluation

- Medicine Lec.9 - Viral Infection IIDocument42 pagesMedicine Lec.9 - Viral Infection II7fefdfbea1Pas encore d'évaluation

- 3Document2 pages3imtiyazh85100% (1)

- Final DraftDocument5 pagesFinal Draftapi-451064930Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bwdi DR, Chemist&Stp Final ListDocument226 pagesBwdi DR, Chemist&Stp Final ListzaheerbcPas encore d'évaluation

- Alumni Communication LetterDocument3 pagesAlumni Communication LetterJoniel Niño Hora BlawisPas encore d'évaluation

- Characterization of Pathogens: We Strive For Wisdom Chapter-2Document29 pagesCharacterization of Pathogens: We Strive For Wisdom Chapter-2AZ Amanii BossPas encore d'évaluation

- Periodic Health ExamDocument23 pagesPeriodic Health ExamPernel Jose Alam MicuboPas encore d'évaluation

- 2441-3300 Kneehab Phy Brochure 2r16Document2 pages2441-3300 Kneehab Phy Brochure 2r16MVP Marketing and DesignPas encore d'évaluation

- Maternal 8Document15 pagesMaternal 8shanikaPas encore d'évaluation

- CHN - Case Study No. 2 Marco Ray VelaDocument5 pagesCHN - Case Study No. 2 Marco Ray VelaMarco VelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Observational Studies Lecture - ReviewDocument3 pagesObservational Studies Lecture - ReviewKelsey AndersonPas encore d'évaluation