Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

WEEK1 1 ProductionPossibilities OpportunityCost

Transféré par

mahadevavrCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

WEEK1 1 ProductionPossibilities OpportunityCost

Transféré par

mahadevavrDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

8

Chapter 1

The Central Idea

International Trade

international trade

the exchange of goods and

services between people or firms

in different nations.

Thus far, we have said nothing about where Emily and Johann live or work. They could

reside in the same country, but they also could reside in different countries. Emily could

live in the United States; Johann, in Germany. If this is so, when Emily purchases

Johanns printing service, international trade will take place because the trade is

between people in two different countries.

The gains from international trade are thus of the same kind as the gains from trade

within a country. By trading, people can better satisfy their preferences for goods (as in the

case of Maria and Adam), or they can better utilize their comparative advantage (as in the

case of Emily and Johann). In either situation, both participants can gain from trade.

REVIEW

All individuals face scarcity in one form or another.

Scarcity forces people to make choices. For every

choice that is made, there is also an opportunity

cost of not doing one thing because another thing

has been chosen.

People benefit from economic interactionstrading

goods and serviceswith other people.

Gains from trade occur because goods and services

can be allocated in ways that are more satisfactory

to people.

Gains from trade also occur because trade permits

specialization through the division of labor. People

should specialize in the production of goods in

which they have a comparative advantage.

Scarcity and Choice for

the Economy as a Whole

Just as individuals face scarcity and choice, so too does the economy as a whole. The

total amount of resources in an economyworkers, land, machinery, and factoriesis

limited. Thus, the economy cannot produce all the health care, crime prevention, education, or entertainment that people want. A choice must be made. Let us first consider

how to represent scarcity and choice in the whole economy and then consider alternative

ways to make those choices.

Production Possibilities

production possibilities

alternative combinations of

production of various goods that

are possible, given the economys

resources.

To simplify things, let us suppose that production in the economy can be divided into

two broad categories. Suppose the economy can produce either computers (laptops,

desktops, servers) or movies (thrillers, love stories, mysteries, musicals). The choice

between computers and movies is symbolic of one of the most fundamental choices individuals in any society must face: how much to invest to produce more or better goods in

the future versus how much to consume in the present. Computers help people produce

more or better goods. Movies are a form of consumption. Other pairs of goods also

could be used in our example. Another popular example is guns versus butter, representing defense goods versus nondefense goods.

With a scarcity of resources, such as labor and capital, a choice exists between producing some goods, such as computers, versus other goods, such as movies. If the economy produces more of one, then it must produce less of the other. Table 1-1 gives an

example of the alternative choices, or the production possibilities, for computers and

Scarcity and Choice for the Economy as a Whole

movies. Observe that six different choices could be made, some with more computers

and fewer movies, others with fewer computers and more movies.

Table 1-1 tells us what happens as available resources in the economy are moved

from movie production to computer production or vice versa. If resources move from

producing movies to producing computers, then fewer movies are produced. For

example, if all of the resources are used to produce computers, then 25,000 computers

and zero movies can be produced, according to the table. If all resources are used to

produce movies, then no computers can be produced. These are two extremes, of

course. If 100 movies are produced, then we can produce 24,000 computers rather

than 25,000 computers. If 200 movies are produced, then computer production must

fall to 22,000.

Increasing Opportunity Costs

The production possibilities in Table 1-1 illustrate the concept of opportunity cost for

the economy as a whole. The opportunity cost of producing more movies is the value of

the forgone computers. For example, the opportunity cost of producing 200 movies

rather than 100 movies is 2,000 computers.

An important economic idea about opportunity costs is demonstrated in Table 1-1.

Observe that movie production increases as we move down the table. As we move from row

to row, movie production increases by the same number: 100 movies. The decline in computer production between the first and second rowsfrom 25,000 to 24,000 computers

is 1,000 computers. The decline between the second and third rowsfrom 24,000 to

22,000 computersis 2,000 computers. Thus, the decline in computer production gets

greater as we produce more movies. As we move from 400 movies to 500 movies, we lose

13,000 computers. In other words, the opportunity cost, in terms of computers, of producing more movies increases as we produce more movies. Each extra movie requires a loss of

more and more computers. What we have just described is called increasing opportunity

costs, with an emphasis on the word increasing.

Why do opportunity costs increase? You can think about it in the following way.

Some of the available resources are better suited for movie production than for computer production, and vice versa. Workers who are good at building computers might

not be so good at acting, for example, or moviemaking may require an area with a dry,

sunny climate. As more and more resources go into making movies, we are forced to

take resources that are much better at computer making and use them for moviemaking. Thus, more and more computer production must be lost to increase movie production by a given amount. Adding specialized computer designers to a movie cast

would be quite costly in terms of lost computers, and it might add little to movie

production.

increasing opportunity cost

a situation in which producing

more of one good requires giving

up an increasing amount of

production of another good.

Table 1-1

Production Possibilities

A

B

C

D

E

F

Movies

Computers

0

100

200

300

400

500

25,000

24,000

22,000

18,000

13,000

0

10

Chapter 1

The Central Idea

Community College Enrollments and the Economic Downturn

Question to Ponder

1. Enrollment at community colleges also grew more

rapidly than at four-year colleges. Can you use opportunity costs to explain that growth?

iStockphoto.com/Moodboard_Images

The fall term of the 20082009 academic year saw record

enrollment increases at community colleges throughout the

United States. Enrollment at Delaware Community College

in Media, Pennsylvania, was up 8.5 percent compared with

typical increases of 3 percent. Enrollment was up an estimated 16 percent at Palm Beach Community College, in

Lake Worth, Florida. According to an August 2008 report

from Inside Higher Education, Though most colleges only

have estimates for their enrollments this fall, many colleges

are projecting increases of around 10 percent over last fall.

What explains this enrollment boom? Changing opportunity costs is the most likely explanation. Grace Truman,

the spokesperson for Palm Beach Community College, put

it this way, Our enrollment growth strongly correlates to

downturns in the economy. Locally, we have had significant

slumps and layoffs, particularly in the housing and construction related industries. Our housing, food and gasoline

costs have risen sharply in the same time period.

In other words, the downturn in the economy

reduced the opportunity cost of going to community college because it made jobs harder to find and less attractive. The unemployment rate in Florida jumped from 4.5

percent to 8.1 percent during the 12 months ending in

December 2008. In Pennsylvania, it rose from 4.4 to 6.7

percent and in the nation as a whole from 4.9 to 7.2 percent. The unemployment rate for teenagers (ages 16 to

19) is always higher than the average and it equaled 21

percent at the end of 2008. In these circumstances, finding a job may take a long time and, when you do find

one, it may not pay as much as in good economic times.

The Production Possibilities Curve

production possibilities

curve

a curve showing the maximum

combinations of production of two

goods that are possible, given the

economys resources.

Figure 1-2 is a graphical representation of the production possibilities in Table 1-1 that

nicely illustrates increasing opportunity costs. We put movies on the horizontal axis and

computers on the vertical axis of the figure. Each pair of numbers in a row of the table

becomes a point on the graph. For example, point A on the graph is from row A of the

table. Point B is from row B, and so on.

When we connect the points in Figure 1-2, we obtain the production possibilities

curve. This curve shows the maximum number of computers that can be produced for each

quantity of movies produced. Note that the curve in Figure 1-2 slopes downward and is

bowed out from the origin. That the curve is bowed out indicates that the opportunity cost of

producing movies increases as more movies are produced. As resources move from computer

making to moviemaking, each additional movie means a greater loss of computer production.

11

Scarcity and Choice for the Economy as a Whole

Figure 1-2

COMPUTERS

(THOUSANDS)

The Production Possibilities

Curve

Efficient

25

B

C

20

I

15

Inefficient

Impossible

E

10

Production possibilities curve

F

MOVIES

(HUNDREDS)

Inefficient, Efficient, or Impossible? The production possibilities curve

shows the effects of scarcity and choice in the economy as a whole. Three situations can

be distinguished in Figure 1-2, depending on whether production is in the shaded area,

on the curve, or outside the curve.

First, imagine production at point I. This point, with 100 movies and 18,000 computers, is inside the curve. But the production possibilities curve tells us that it is possible

to produce more computers, more movies, or both with the same amount of resources.

For some reason, the economy is not working well at point I. For example, a talented

movie director may be working on a computer assembly line because her short film has

not yet been seen by studio executives, or perhaps a financial crisis has prevented computer companies from getting loans and thus disrupted all production of computer chips.

Points inside the curve, like point I, are inefficient because the economy could produce a

larger number of movies, as at point D, or a larger number of computers, as at point B.

Points inside the production possibilities curve are possible, but they are inefficient.

Second, consider points on the production possibilities curve. These points are efficient. They represent the maximum amount that can be produced with available resources. The only way to raise production of one good is to lower production of the other

good. Thus, points on the curve show a trade-off between one good and another.

Third, consider points to the right and above the production possibilities curve, like

point J in Figure 1-2. These points are impossible. The economy does not have the

resources to produce those quantities.

Shifts in the Production Possibilities Curve The production possibilities

curve is not immovable. It can shift out or in. For example, the curve is shown to shift out

Each point on the curve shows

the maximum number of

computers that can be produced

when a given amount of movies

is produced. The points with

letters are the same as those in

Table 1-1 and are connected by

smooth lines. Points in the

shaded area inside the curve are

inefficient. Points outside the

curve are impossible. For the

efficient points on the curve, the

more movies that are produced,

the fewer computers that are

produced. The curve is bowed

out because of increasing

opportunity costs.

12

Chapter 1

The Central Idea

Figure 1-3

Shifts in the Production

Possibilities Curve

The production possibilities

curve shifts out as the economy

grows. The maximum numbers

of movies and computers that

can be produced increase.

Improvements in technology,

more machines, or more labor

permits the economy to produce

more.

COMPUTERS

(THOUSANDS)

35

New production

possibilities curve

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

Old production

possibilities curve

MOVIES

8

(HUNDREDS)

in Figure 1-3. More resourcesmore workers, for example, or more cameras, lights, and

studioswould shift the production possibilities curve out. A technological innovation that

allowed one to edit movies faster also would shift the curve outward. When the production

possibilities curve shifts out, the economy grows because more goods and services can be

produced. The production possibilities curve need not shift outward by the same amount

in all directions. The curve could move up more than it moves to the right, for example.

As the production possibilities curve shifts out, impossibilities are converted into possibilities. Some of what was impossible for the U.S. economy in 1975 is possible now. Some of

what is impossible now will be possible in 2035. Hence, the economists notion of possibilities

is a temporary one. When we say that a certain combination of computers and movies is

impossible, we do not mean forever impossible, we mean only currently impossible.

Scarcity, Choice, and Economic Progress However, the conversion of

impossibilities into possibilities is also an economic problem of choice and scarcity: If we

invest less nowin machines, in education, in children, in technologyand consume

more now, then we will have less available in the future. If we take computers and movies

as symbolic of investment and consumption, then choosing more investment will result in

a larger outward shift of the production possibilities curve, as illustrated in Figure 1-4.

More investment enables the economy to produce more in the future.

The production possibilities curve represents a trade-off, but it does not mean that

some people win only if others lose. First, it is not necessary for someone to lose in order

for the production possibilities curve to shift out. When the curve shifts out, the production of both items increases. Although some people may fare better than others as the production possibilities curve is pushed out, no one necessarily loses. In principle, everyone

can gain. Second, if the economy is at an inefficient point (like point I in Figure 1-2), then

production of both goods can be increased with no trade-off. In general, therefore, the

economy is more like a win-win situation, where everyone can achieve a gain.

13

Scarcity and Choice for the Economy as a Whole

Figure 1-4

Shifts in the Production Possibilities Curve Depend on Choices

On the left, few resources are devoted to investment for the future; hence, the production possibilities curve shifts only a little over

time. On the right, more resources are devoted to investment and less to consumption; hence, the production possibilities curve

shifts out by a larger amount over time.

INVESTMENT

GOODS

INVESTMENT

GOODS

35

35

30

30

25

25

implies

low growth.

20

20

15

15

10

High

investment

10

Low

investment

implies

high growth.

5

1

CONSUMPTION GOODS

CONSUMPTION GOODS

REVIEW

The production possibilities curve represents the

choices open to a whole economy when it is confronted with a scarcity of resources. As more of

one item is produced, less of another item must be

produced. The opportunity cost of producing more

of one item is the reduced production of another

item.

The production possibilities curve is bowed out

because of increasing opportunity costs.

Points inside the curve are inefficient. Points on the

curve are efficient. Points outside the curve are

impossible.

The production possibilities curve shifts out as

resources increase.

Outward shifts of the production possibilities curve

or moves from inefficient to efficient points are the

reasons why the economy is not a zero-sum game,

despite the existence of scarcity and choice.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Design Calculation FOR Rigid Pavement/RoadDocument5 pagesDesign Calculation FOR Rigid Pavement/RoadghansaPas encore d'évaluation

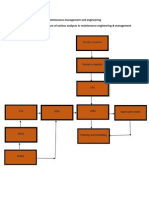

- Organizational Structure and DesignDocument89 pagesOrganizational Structure and DesignmahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- ITP - Plaster WorkDocument1 pageITP - Plaster Workmahmoud ghanemPas encore d'évaluation

- MULTIPLE CHOICE QUESTIONS IN TAX REVIEW Jan 5Document1 pageMULTIPLE CHOICE QUESTIONS IN TAX REVIEW Jan 5Quasi-Delict89% (18)

- Aspen Plus User ModelsDocument339 pagesAspen Plus User Modelskiny81100% (1)

- AZ 103T00A ENU TrainerHandbook PDFDocument403 pagesAZ 103T00A ENU TrainerHandbook PDFlongvietmt100% (2)

- Science, Technology and Society Module #1Document13 pagesScience, Technology and Society Module #1Brent Alfred Yongco67% (6)

- Conclusions PHDDocument6 pagesConclusions PHDmahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- 4 Analytics EmletDocument42 pages4 Analytics EmletmahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- Marketing Strategy and ManagementDocument1 pageMarketing Strategy and ManagementmahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- PHD Fee All The BacthesDocument2 pagesPHD Fee All The BacthesmahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- QP MKT STRG 2012Document4 pagesQP MKT STRG 2012mahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- Pepsi CaseDocument13 pagesPepsi CasemahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- Scope and Significance of Personal Selling and Sales ManagementDocument41 pagesScope and Significance of Personal Selling and Sales ManagementmahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- Chicken Pox Measles Conjunctivitis Pneumonia: Communicable DiseasesDocument1 pageChicken Pox Measles Conjunctivitis Pneumonia: Communicable DiseasesmahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- The Importance of Public RelationsDocument7 pagesThe Importance of Public RelationsmahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- Welcome To Tds Awareness / E-Filing of TDS Returns PROGRAMMEDocument60 pagesWelcome To Tds Awareness / E-Filing of TDS Returns PROGRAMMEmahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- Show Me College Success Skills: Student/Class GoalDocument22 pagesShow Me College Success Skills: Student/Class GoalmahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- LezingjoostDocument29 pagesLezingjoostmahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- QP Mutual Fund AgentDocument30 pagesQP Mutual Fund AgentmahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- MBTIDocument25 pagesMBTImahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- Welcome To Tds Awareness / E-Filing of TDS Returns PROGRAMMEDocument60 pagesWelcome To Tds Awareness / E-Filing of TDS Returns PROGRAMMEmahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- Inteq Big Data Requirements Analysis Overview 2013Document2 pagesInteq Big Data Requirements Analysis Overview 2013mahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- Broker and ResponsibilitiesDocument19 pagesBroker and ResponsibilitiesmahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- Asia's Best B-School ReportDocument16 pagesAsia's Best B-School ReportmahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- Overall RankDocument8 pagesOverall RankmahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- Doing The Gatr Rock: Motivating Your Customers and EmployeesDocument19 pagesDoing The Gatr Rock: Motivating Your Customers and EmployeesmahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- NET EXAM Paper 1Document27 pagesNET EXAM Paper 1shahid ahmed laskar100% (4)

- by StateDocument4 pagesby StatemahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- Full Text 01Document67 pagesFull Text 01Sundus AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- Stanford FictionDocument1 pageStanford FictionmahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- 1993 Apr Jun 41 55 Fujitsu (A) Operations CaseDocument15 pages1993 Apr Jun 41 55 Fujitsu (A) Operations CasemahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- Personality AssessmentDocument2 pagesPersonality AssessmentmahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- Industry: Advertising Advertising Advertising AdvertisingDocument6 pagesIndustry: Advertising Advertising Advertising AdvertisingmahadevavrPas encore d'évaluation

- Tensile Strength of Ferro Cement With Respect To Specific SurfaceDocument3 pagesTensile Strength of Ferro Cement With Respect To Specific SurfaceheminPas encore d'évaluation

- Certified Vendors As of 9 24 21Document19 pagesCertified Vendors As of 9 24 21Micheal StormPas encore d'évaluation

- Curriculum Improvement v2Document47 pagesCurriculum Improvement v2Nica Lagrimas100% (1)

- He Sas 23Document10 pagesHe Sas 23Hoorise NShinePas encore d'évaluation

- IDL6543 ModuleRubricDocument2 pagesIDL6543 ModuleRubricSteiner MarisPas encore d'évaluation

- Static Power Conversion I: EEE-463 Lecture NotesDocument48 pagesStatic Power Conversion I: EEE-463 Lecture NotesErgin ÖzdikicioğluPas encore d'évaluation

- 01 IntroductionDocument15 pages01 IntroductionAli FarhatPas encore d'évaluation

- Ch.1 Essential Concepts: 1.1 What and How? What Is Heat Transfer?Document151 pagesCh.1 Essential Concepts: 1.1 What and How? What Is Heat Transfer?samuel KwonPas encore d'évaluation

- Backward Forward PropogationDocument19 pagesBackward Forward PropogationConrad WaluddePas encore d'évaluation

- 3-Waves of RoboticsDocument2 pages3-Waves of RoboticsEbrahim Abd El HadyPas encore d'évaluation

- SHAW Superdew 3 Specification SheetDocument3 pagesSHAW Superdew 3 Specification SheetGeetha ManoharPas encore d'évaluation

- Company Profile PT. Geo Sriwijaya NusantaraDocument10 pagesCompany Profile PT. Geo Sriwijaya NusantaraHazred Umar FathanPas encore d'évaluation

- PLASSON UK July 2022 Price Catalogue v1Document74 pagesPLASSON UK July 2022 Price Catalogue v1Jonathan Ninapaytan SanchezPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 2 DIPDocument33 pagesModule 2 DIPdigital lovePas encore d'évaluation

- 4.1 Hydrostatic Force On Curved Surfaces - CE 309-CE22S2 - Fluid MechanicsDocument4 pages4.1 Hydrostatic Force On Curved Surfaces - CE 309-CE22S2 - Fluid MechanicsRUSSELPas encore d'évaluation

- Video Tutorial: Machine Learning 17CS73Document27 pagesVideo Tutorial: Machine Learning 17CS73Mohammed Danish100% (2)

- Package-Related Thermal Resistance of Leds: Application NoteDocument9 pagesPackage-Related Thermal Resistance of Leds: Application Notesalih dağdurPas encore d'évaluation

- Overview of MEMDocument5 pagesOverview of MEMTudor Costin100% (1)

- Hawassa University Institute of Technology (Iot) : Electromechanical Engineering Program Entrepreneurship For EngineersDocument133 pagesHawassa University Institute of Technology (Iot) : Electromechanical Engineering Program Entrepreneurship For EngineersTinsae LirePas encore d'évaluation

- Stevenson Chapter 13Document52 pagesStevenson Chapter 13TanimPas encore d'évaluation

- Activity 2Document5 pagesActivity 2DIOSAY, CHELZEYA A.Pas encore d'évaluation

- FmatterDocument12 pagesFmatterNabilAlshawish0% (2)

- 2022 Summer Question Paper (Msbte Study Resources)Document4 pages2022 Summer Question Paper (Msbte Study Resources)Ganesh GopalPas encore d'évaluation

- Agenda - Meeting SLC (LT) - 27.06.2014 PDFDocument27 pagesAgenda - Meeting SLC (LT) - 27.06.2014 PDFharshal1223Pas encore d'évaluation

- Logarithms Functions: Background Information Subject: Grade Band: DurationDocument16 pagesLogarithms Functions: Background Information Subject: Grade Band: DurationJamaica PondaraPas encore d'évaluation