Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Amri Piracy in Southeast Asia Almost Final

Transféré par

Agus GuardedCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Amri Piracy in Southeast Asia Almost Final

Transféré par

Agus GuardedDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Piracy in Southeast Asia: An Overview of International and Regional Efforts

by Ahmad Almaududy Amri*

One of the main maritime security threats in Southeast Asia is Piracy. While

piracy has been a perennial problem, this threat has received increasing attention in the

region over the past few years. Reports published by the International Maritime

Organization (IMO) as well as the International Maritime Bureau show an alarming

number of piratical acts in Southeast Asian waters over the past decade.1 Southeast Asia

had the second highest number of piracy attacks in the world from 20082012.2 Only the

African Region transcended Southeast Asia in the number of attacks. This is concerning

because the geographical location of the region is very important to world trade.

Southeast Asia contains several highly-trafficked sea lanes and straits which are used

for international trade. Indeed, five out of the twenty-five busiest ports in the world are

located in Southeast Asia.3

Fortunately, states are making serious efforts at the international as well as

regional level to combat piracy. This essay explores some of the international and

regional efforts that countries in Southeast Asia have made to fight piracy and identifies

some of their benefits and shortcomings.

International Efforts

As the Security Council has repeatedly affirmed, international law, as reflected in

the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), presents the primary

legal framework for combating piracy and armed robbery at sea.4 The UNCLOS, which

Ahmad Almaududy Amri is a PhD candidate at the Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources and

Security (ANCORS), University of Wollongong, where he is writing his thesis on maritime security challenges

in Southeast Asia. Mr. Amri holds a Master of International Relations from the University of Indonesia, a

Master of Laws from Gadjah Mada University, and a Bachelor of Laws from the University of North Sumatra.

1 See, e.g., INTL MARITIME ORG., REPORT ON ACTS OF PIRACY AND ARMED ROBBERY AGAINST SHIPS 1516 (2011)

(listing the acts of piracy and armed robbery committed in the Malacca Strait during 2011); ICC INTL MARITIME

BUREAU, PIRACY AND ARMED ROBBERY AGAINST SHIPS 5 (2012).

2 See id.

3 See Top 50 World Container Ports, WORLD SHIPPING COUNCIL, http://www.worldshipping.org/about-theindustry/global-trade/top-50-world-container-ports (last visited Jan. 9, 2014).

4 See, e.g., S. C. Res. 1976, at 2, U.N. Doc. S/RES/1976 (Apr. 11, 2011).

*

129

CORNELL INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL ONLINE

Vol. 1

has been ratified by nearly all of Southeast Asia,5 obliges state signatories to cooperate

to the fullest possible extent in the repression of piracy 6 and lays out the rules for doing

so in articles 100 through 107.7

Article 101 defines piracy to include any illegal acts of violence or detention . . .

committed for private ends by the crew . . . of a private ship . . . and directed against

another ship or aircraft or the people or property on board, where the acts were

committed on the high seas or outside the jurisdiction of any state.8 If a state identifies a

pirate ship on the high seas, UNCLOS allows it to seize the ship, arrest the persons on

board, and seize any property on board.9 In this way, the UNCLOS gives states a great

deal of leeway to combat piracy on the high seas. However, one of the weaknesses of

the UNCLOS is that its definition of piracy does not includes attacks conducted in

territorial seas.10 Thus, if an attack occurs in a countrys territorial waters, another state

may not have the authority to seize the pirate vessel, even if its own ship is the victim of

the attack.11

Another legal instrument used to combat piracy is the Convention for the

Suppression of Unlawful Acts against the Safety of Maritime Navigation (SUA

Convention).12 While the SUA Convention does not specifically aim to address piracy,

piratical acts are subject to the SUA Convention.13 Under Article 3, a person commits an

offence if that person seizes or exercises control over a ship by for force or threat of

force or performs an act of violence against a person board a ship if that act is likely to

endanger the safe navigation of that ship.14 In this way, the SUA Convention fills some

of the gaps in the UNCLOS. Under the SUA convention, an offense does not require an

5 Only Cambodia has not ratified the UNCLOS. See Status of the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, U.N.

TREATY COLLECTION (Jan. 8, 2014),

https://treaties.un.org/pages/viewdetailsIII.aspx?&mtdsg_no=XX~6&chapter=21&temp=mtdsg3&lang=en.

6 See United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea art. 100, Dec. 10, 1982, 1833 U.N.T.S. 397

[hereinafter UNCLOS].

7 See id. arts. 100107.

8 Id. art. 101.

9 Id. art. 105.

10 See id. art. 101.

11 See Jill Harrelson, Blackbeard Meets Blackwater: An Analysis of International Conventions that Address

Piracy and the Use of Private Security Companies to Protect the Shipping Industry, 25 AM. U. INTL L. REV. 283,

29293 ([S]tates have jurisdiction over pirates if they are captured on the high seas. In contrast . . . a state

has complete sovereignty over its territorial seas.).

12 Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts against the Safety of Maritime Navigation, Mar. 10,

1988, 1678 U.N.T.S. 222 [hereinafter SUA Convention].

13 The SUA Convention was initiated after the politically-motivated hijacking of the Italian cruise ship,

Achille Lauro, in 1988. Harrelson, supra note 11, at 293. Unfortunately, Article 101 of the UNCLOS did not

apply to the hijacking. See ROBIN GEISS & ANNA PETRIG, PIRACY AND ARMED ROBBERY AT SEA 62 (2011). Therefore,

states found it necessary to create a legally binding instrument that would apply to criminal acts committed

at sea for political and other ends. Id.

14 SUA Convention, supra note 12, art. 3.

130

CORNELL INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL ONLINE

Vol. 1

attack to involve two ships or to occur on the high seas or in another area beyond

national jurisdiction.15 If a state apprehends an offender, it is required to either

prosecute him or extradite him to the country that will.16

However, the SUA Convention is not a panacea for piracy. Like the UNCLOS, a

party to the SUA Convention cannot venture into the territorial waters of another

country to capture an offender.17 Also, the SUA Convention has not been popular in

Southeast Asia: Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand have not acceded to the SUA

Convention 1988,18 and none of the states in the region have signed the Conventions

2005 Protocol.19

Regional Efforts

In 2004, several Southeast Asian countries adopted the Regional Cooperation

Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery (ReCAAP).20 The Agreement,

which came into force on 4th of September 2006, uses the same definition of piracy as

Article 101 of the UNCLOS.21 The ReCAAP also adopts the IMOs definition of armed

robbery from its Code of Practice on the investigation of crimes against ships.22 Where

there is an act of piracy, the ReCAAP provides extradition measures. According to

Article 12, member states in accordance with their respective national laws must

cooperate to extradite a person who has committed an act of piracy or armed robbery.23

In this way, the ReCAAP has in part served as the Southeast Asian alternative to the

SUA Convention.24

See id.

See id. art. 10; Jason Power, Maritime Terrorism: A New Challenge for National and International

Security, 10 BARRY L. REV. 111, 127 (2008).

17 Harrelson, supra note 11, at 294.

18 See United Nations Treaty Series Online Collection: Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts

Against the Safety of Maritime Navigation, U.N. TREATY SERIES,

https://treaties.un.org/Pages/showdetails.aspx?objid=08000002800b9bd7 (last visited Jan. 9, 2014).

19 See INTL MARITIME ORG., STATUS OF MULTILATERAL CONVENTIONS AND INSTRUMENTS IN RESPECT OF WHICH THE

INTERNATIONAL MARITIME ORGANIZATION OR ITS SECRETARY-GENERAL PERFORMS DEPOSITARY OR OTHER FUNCTIONS 418

33 (Jan. 9, 2014), available at

http://www.imo.org/about/conventions/statusofconventions/documents/status - 2014 New Version.pdf.

20 Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships in Asia, Nov.

11, 2004, 2398 U.N.T.S. 201 [hereinafter ReCAAP]. See generally GEISS & PETRIG, supra note 13.

21 See UNCLOS, supra note 6, art. 101; ReCAAP, supra note 20, art. 1.

22 See id.; INTL MARITIME ORG., CODE OF PRACTICE FOR THE INVESTIGATION OF CRIMES OF PIRACY AND ARMED

ROBBERY AGAINST SHIPS 4 (2010).

23 ReCAAP, supra note 20, art. 12.

24 However, two important Southeast Asian states, Indonesia and Malaysia have not acceded to the

ReCAAP. See United Nations Treaty Series Online Collection: Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating

Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships in Asia, U.N. TREATY SERIES,

https://treaties.un.org/Pages/showdetails.aspx?objid=08000002800624d1 (last visited Jan. 9, 2014).

15

16

131

CORNELL INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL ONLINE

Vol. 1

The ReCAAP also has it shortcomings. As a regional measure, the ReCAAP does

not supersede the enforcement measures of UNCLOS. In line with this view, it does not

allow member states to seize pirate ships in other states territorial seas. Also ReCAAP

is incapable of having a large impact in terms of joint maritime enforcement operations

because its provisions are mostly limited to information sharing.25

In order to fill this operational gap, several countries have begun other regional

efforts to suppress piracy, particularly in Malacca Strait. The first of these, known as

Operation MALSINDO, was launched in July 2004 and involved navies from three

littoral states in Southeast Asia: Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia.26 Its task was to

conduct coordinated patrols within the countries respective territorial seas around the

Strait of Malacca. Since its launch, countries in the region have also supplemented the

MALSINDO effort by the launching aerial patrols over the Malacca Strait under the

Eyes in the Sky (EiS) plan.27 In 2006, the Malacca Strait Patrols (MSP) was formed which

brought together the MALSINDO and the EiS efforts.28 Since the formation of the MSP,

Thailand has also joined MALSINDO and the EiS.29

As a result of these efforts, there has been a substantial drop in the number of

piracy attacks in the Malacca Strait.30 However, one of the weaknesses of the MSP is the

effort does not allow for cross-border pursuits through other states territorial seas, as

this is viewed as an interference with other states sovereignty.31

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has also made an effort to

combat piratical attacks. ASEAN has been committed to discussing issues related to

maritime security in its regular meetings. As the result, there are three prominent

forums which address maritime security, namely the ASEAN Maritime Forum, the

ASEAN Regional Forum Inter-Sessional Meeting on Maritime Security, and the

Maritime Security Expert Working Group.32 However, despite these efforts, the ASEAN

forums are largely regarded as talk shops. Hence, in terms of coordinated efforts among

ASEAN states, a more technical effort may be needed.

See ReCAAP, supra note 20, arts. 79. But see arts. 1011 (concerning cooperation in detecting pirates,

armed robbers, or their victims).

26 See Catherine Z. Raymond, Piracy and Armed Robbery in the Malacca Strait: A Problem Solved?, NAVAL

WAR C. REV. 31, 3638.

27 See id.

28 Id. at 38

29 Malacca Strait Patrols, OCEANS BEYOND PIRACY, http://oceansbeyondpiracy.org/matrix/malacca-straitpatrols (last visited Jan. 9, 2014); see also id.

30 See id. at 31, 36; Malacca Strait Patrols, supra note 29.

31 See Raymond, supra note 26, at 36.

32 See Sam Bateman, Solving the "Wiched Problems" of Maritime Security: Are Regional Forums up to the

Task?, 33 CONTEMP. SOUTHEAST ASIA 1 (2011).

25

132

CORNELL INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL ONLINE

Vol. 1

Conclusion

Despite the fall in attacks in the Malacca Strait,33 piracy is still a serious problem

in Southeast Asia, as the threat of piracy affects international commerce and human

safety. Moreover, the international legal framework, including the UNCLOS and the

SUA Convention, seem to be inadequate to resolve the problem.34 The narrow definition

of piracy in the UNCLOS does not encompass many of the piratical acts occurring in the

region. Piracy often occurs in territorial sea whereas the UNCLOS only deals with

piratical acts on the high seas.35 Also, while the SUA Convention fills some of the gaps

left by the UNCLOS, it is not popular among the countries of the region. Indeed, two of

the most important littoral states in the region, Indonesia and Malaysia, are not party to

the SUA Convention or its protocol.36

The regional legal framework also seems to be inadequate in resolving the

problem. The ReCAAP has a small impact in terms of joint maritime enforcement

operations. Also, like the SUA Convention, Indonesia and Malaysia have not acceded to

the ReCAAP. Regarding the efforts of ASEAN, the Associations forums are merely talk

shops and likely have an even smaller impact than ReCAAP.

Recognizing that the MSP played a significant role in the suppression of piracy in

the Strait of Malacca, similar efforts involving a larger number of countries in the region

could be a part of the solution. While additional efforts based on the MSP would not

allow for cross-border pursuits into territorial waters, this may actually be beneficial, as

concerns about sovereignty have been some of the biggest barriers to multilateral

cooperation. Under an approach similar to the MSP, countries could develop and

promote a cooperative mindset while maintaining their territorial sovereignty.

See Raymond, supra note 26, at 31.

See generally Erik Barrios, Casting a Wider net: addressing the maritime piracy problem in Southeast

Asia, 28 B.C. INT'L & COMP. L. REV. 149. (2005).

35 Id.

36 See supra notes 1819.

33

34

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- John Robert KlinnerDocument30 pagesJohn Robert KlinnerAlan Jules WebermanPas encore d'évaluation

- Definition of Diplomatic AgentDocument3 pagesDefinition of Diplomatic AgentAdv Faisal AwaisPas encore d'évaluation

- People V GalloDocument9 pagesPeople V GalloSecret SecretPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Victor Arias-Montoya, 967 F.2d 708, 1st Cir. (1992)Document12 pagesUnited States v. Victor Arias-Montoya, 967 F.2d 708, 1st Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Apply for Security Business LicenseDocument2 pagesApply for Security Business LicenseMafeth Concepcion84% (19)

- Criminal Law II Midterms SamplexDocument3 pagesCriminal Law II Midterms SamplexLovelle Marie RolePas encore d'évaluation

- Alcohol PolicyDocument1 pageAlcohol PolicyBritney JacksonPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Ernest Charles Downs, United States of America v. Larry Dee Johnson, United States of America v. John Dennis Koop, 412 F.2d 315, 10th Cir. (1969)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Ernest Charles Downs, United States of America v. Larry Dee Johnson, United States of America v. John Dennis Koop, 412 F.2d 315, 10th Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Employment Contract: Know All Men by These PresentsDocument4 pagesEmployment Contract: Know All Men by These PresentsAldrin Mendiola QuebecPas encore d'évaluation

- Citizenship TrainingDocument5 pagesCitizenship TrainingAngela NavarroPas encore d'évaluation

- The Provincial Motor Vehicles Ordinance, 1965, (West Pakistan Ordinance No. Xix of 1965) - Chapter-I PRELIMINARY SectionsDocument113 pagesThe Provincial Motor Vehicles Ordinance, 1965, (West Pakistan Ordinance No. Xix of 1965) - Chapter-I PRELIMINARY SectionsMurash javaidPas encore d'évaluation

- Cover Letter Cease and Desist Abusive Collection IRS ScrubbedDocument2 pagesCover Letter Cease and Desist Abusive Collection IRS ScrubbedMark AustinPas encore d'évaluation

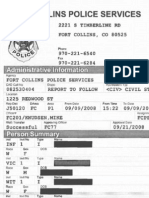

- Fort Collins Police Reports On Scientology's Drug Rehab Narconon (A Life Worth Living)Document209 pagesFort Collins Police Reports On Scientology's Drug Rehab Narconon (A Life Worth Living)snippyxPas encore d'évaluation

- Crime Incident Report Template PDFDocument2 pagesCrime Incident Report Template PDFJOANNEPas encore d'évaluation

- Kruidbos - Cheryl PeekDocument34 pagesKruidbos - Cheryl PeekThe Conservative TreehousePas encore d'évaluation

- Ejercito vs. SandiganbayanDocument113 pagesEjercito vs. SandiganbayanVikki AmorioPas encore d'évaluation

- Bolinao Electronics Corporation Vs Brigido ValenciaDocument2 pagesBolinao Electronics Corporation Vs Brigido ValenciaShiela PilarPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson 8 Opportunities Challenges Problems and Issues in Media and InformationDocument24 pagesLesson 8 Opportunities Challenges Problems and Issues in Media and InformationRENALYN IMPERIALPas encore d'évaluation

- First-Name (Abbas) Last-Name (Ghanem) State (ALL) Jurisdiction (ALL) Radius (30) 2Document206 pagesFirst-Name (Abbas) Last-Name (Ghanem) State (ALL) Jurisdiction (ALL) Radius (30) 2My-Acts Of-SeditionPas encore d'évaluation

- Microsoft Word - MyReviewer Notes CRIMINAL 2 - RunningDocument53 pagesMicrosoft Word - MyReviewer Notes CRIMINAL 2 - RunningMRBPas encore d'évaluation

- Persons and Family Relations 1st and 2nd Exam Reviewer 1Document52 pagesPersons and Family Relations 1st and 2nd Exam Reviewer 1NealPatrickTingzon50% (4)

- Lapuz Sy Vs EufemioDocument2 pagesLapuz Sy Vs EufemioKaye Mendoza100% (1)

- LU 3 - Crimes Against Life & Bodily Integrity.Document77 pagesLU 3 - Crimes Against Life & Bodily Integrity.Mbalenhle NdlovuPas encore d'évaluation

- Motion Stay Writ Possession Foreclosure CaseDocument2 pagesMotion Stay Writ Possession Foreclosure CaseLibio Calejo60% (10)

- Bar Review Tips - RMArceo PDFDocument4 pagesBar Review Tips - RMArceo PDFsecretmystery100% (1)

- C3h2 - 4 People v. DurananDocument2 pagesC3h2 - 4 People v. DurananAaron AristonPas encore d'évaluation

- Context Clues Advanced P1 3Document3 pagesContext Clues Advanced P1 3celiawyf0% (1)

- Police Regulation of Bengal & Jail CodeDocument12 pagesPolice Regulation of Bengal & Jail CodeninjaPas encore d'évaluation

- Answer To Cross ClaimDocument5 pagesAnswer To Cross ClaimJeff SantosPas encore d'évaluation

- Consti II Case List Sec 1-2-2Document15 pagesConsti II Case List Sec 1-2-2Carla VirtucioPas encore d'évaluation