Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Carmelo Garcia v. Mayor Zimmer, Et. Al

Transféré par

GrafixAvenger0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

4K vues79 pagesFiled Januaary 23, 2014- Amended Complaint against Mayor Zimmer, et. charged include discrimination and violation of his civil rights.

Titre original

Carmelo Garcia v. Mayor Zimmer, et. al

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentFiled Januaary 23, 2014- Amended Complaint against Mayor Zimmer, et. charged include discrimination and violation of his civil rights.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

4K vues79 pagesCarmelo Garcia v. Mayor Zimmer, Et. Al

Transféré par

GrafixAvengerFiled Januaary 23, 2014- Amended Complaint against Mayor Zimmer, et. charged include discrimination and violation of his civil rights.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 79

LOUIS A. ZAYAS, ESQ.

LAW OFFICES OF LOUIS A. ZAYAS, LLC

8901 Kennedy Boulevard, 5" Floor

North Bergen, N.J. 07047

Counsel for the Plaintiff Carmelo Garcia

Tel: (201) 977-2900

CARMELO GARCIA

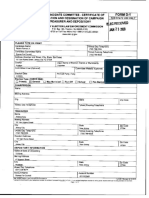

SUPERIOR COURT OF NEW JERSEY.

Plaintiff. LAW DIVISION: HUDSON COUNTY

DOCKET No.: HUD-L-3818-13

DAWN ZIMMER, In her Official and ce

Individual Capacity as Mayor of Hoboken;

HOBOKEN HOUSING AUTHORITY,

Commissioner JAKE STUVIER, In his

Official and Individual Capacity as Housing

Authority Chairman; and STAN GOSSBARD

AMENDED COMPLAINT

Defendants.

‘The Plaintiff, Carmelo Garcia, by and through his attorney, Louis A. Zayas, Esq.,

of the Law Offices of Louis A. Zayas, LLC, alleges as follows:

PAR

1 Plaintiff Carmelo Garcia (“Director Garcia”) is a Hispanic citizen of

New Jersey, residing in Hoboken, New Jersey, and is employed as the Executive Director

of the Hoboken Housing Authority (“HHA’).

2 Defendant Mayor Dawn Zimmer (“Mayor Zimmer”) is a white citizen of

the State of New Jersey, resident of the City of Hoboken, and elected mayor of the City

of Hoboken, Mayor Zimmer is sued in her official and individual capacity for purposes of

effecting the compensatory, and punitive damages demanded by the Plaintiff.

3 Defendant Chairman Jake Stuvier (“Chairman Stuvier”) is a white

citizen of the State of Pennsylvania, and Chairman on the Hoboken Housing Authority

CHHA”) Board of Commissioners. Chairman Stuvier is sued in his official and

individual capacity for purposes of effecting the compensatory, and punitive damages

demanded by the Plaintiff.

4. Defendant Stan Grossbard (“Grossbard”) is a white citizen of New

Jersey, residing in Hoboken. Grossbard and is sued in his individual capacity for

Purposes of effectuating the compensatory, and punitive damages demanded by Plaintiff

5, Defendant Hoboken Housing Authority (“HHA”) is publi entity created

by virtue of New Jersey State Law. ‘The HIJA is sued for purposes of effecting the

‘compensatory and punitive damages demanded by Plaintiff.

FACTS

6 In September 2002, Mayor Zimmer and her husband, Grossbard,

relocated to Hoboken from Manhattan, New York. Soon afier moving to Hoboken,

Mayor Zimmer and Grossbard embarked on a scheme to transform Hoboken in a haven

for mostly white, affluent residents from outside of Hoboken consistent with their own

political, cultural, and racial derivation,

7. In furtherance of this unwritten policy, Mayor Zimmer and Grossbard

conspired with each other to implement their unwritten poliey by replacing the “Old

Guard,” a term commonly used to identify long-term Hobokenites who are generally

made up of blue collar, mostly Italians, Hispanics, and African Americans families, and

replacing them with the “New Guard,” a group that consist of mostly white-collar, white

residents who were not historically fom Hoboken or Hudson County.

8 In pursuit of public office, Mayor Zimmer has sought and received most

of her political support from the “New Guard” while ignoring and receiving little political

immer and

support from the “Old Guard.” Since taking public office as mayor, Mayor

Grossbard conspired to reward govemment jobs and contracts to those individuals and

corporations perceived as belonging to or supportive of the “New Guard.”

9. Conversely, Mayor Zimmer and Grossbard conspired with others,

including Chairman Stuvier and others on HHA Board, to deprive government contracts

and employment opportunities to those associated or aligned with the “Old Guard.”

10. For example, Mayor Zimmer and her administration retaliated against

Anthony Falco, the Hoboken Chief of Police, (“Chief Falco”) because Mayor Zimmer

perceived him to be poli

ically affiliated with the “Old Guard.” According to a federal

lawsuit filed by Chief

Falco, he alleges in part that Mayor Zimmer deprived him of

significant employment benefits, such as uniform allowance, overtime compensation, and

other tangible benefits, because of his perceived politically affiliation with the “Old

Guard,” According to Chief Falco, Mayor

mer and her administration targeted “Old

Guard” employees for harsh treatment than New Guard employees.

11, In furtherance of their scheme to replace the “Old Guard” from

Hoboken, Mayor Zimmer and Grossbard implemented an unwritten policy of political

patronage or “pay-to- play" to reward their political supporters through government

contracts and employment opportuni

es, benefits, and other government privileges and

benefits not otherwise available to their non-political supporters, such as members of the

“Old Guard.”

12, Mayor Zimmer and Grossbard sought (and successfully obtained)

Political control of the Hoboken Housing Authority as a means to implement Mayor

Zimmer’s policies conceming the HHA. However, Mayor Zimmer and Grossbard

required the HHA executive director’s cooperation to successfully implement her

patronage policy of rewarding government contracts to professionals that politically

support Mayor Zimmer,

2B. The Hoboken Housing Authority is suppose to be an autonomous public

housing agency, created under and subject to N.J.S.A. 40A:12A and various federal

regulations. The aforementioned laws and regulations were enacted to shield HHA from

unlawful political interference and influenee.

14, N.L.S.A. 40A:12A, the “Local Redevelopment and Housing Law,” was

enacted to oversee federally-subsidized, low-income residential buildings within the State

of New Jersey. Pursuant to N.J.S.A 40A:12A, the HHA employs an executive director to

manage and oversee the day-to-day operations of the HHA.

15, The HHA board is made up of seven members who implement policy

and oversee the executive director. The HHA board members ate appointed by the

govemor (1 appointee), the mayor (I appointee) and City Couneil (S appointees).

16, On September 1, 2010, HHA hired Garcia as its executive director to a

five-year employment contract. ‘The aforementioned employment contract is generally

renewed as a formality absent any work deficiency. ‘The position of executive director

does not require any political affiliation or association as a condition of employment,

17, Since his employment with the HHA, Director Garcia has performed

duties and responsibilities in an exemplary manner, receiving numerous awards and

commendations for himself and the HHA.

18, Based on his training and experience, Director Garcia was taught that

political influence or interference with the HHA, particular as it regards the procurement

process, was illegal and prohibited.

19, As part of his duties and responsibilities, Director Garcia is responsible

for overseeing the procurement process in awarding government contracts to professional

vendors seeking to do business with the HHA. As a part of the procurement process,

Director Garcia is required to comply with various regulations and laws, including 24

CER. 85.36, which is governs the entire procurement process. In pertinent part, 24

CIR. 85.36, provides:

(a) States. When procuring property and services under a grant, a State will

follow the same policies and procedures it uses for procurements from its non-

Federal funds, The State will ensure that every purchase order or other contract

inclades any clauses required by Federal statutes and executive orders and their

implementing regulations. Other grantees and subgrantees will follow paragraphs

(b) through (i) in this section.

(b) Grantees and subgrantees will use their own procurement procedures which

reflect applicable State and local laws and regulations, provided that the

procurements conform to applicable Federal law and the standards identified in

section,

(©) Grantees and subgrantees will maintain a written code of standatds of conduct

governing the performance of their employees engaged in the award and

administration of contracts. No employee, officer or agent of the grantee or

subgrantee shall participate in selection, or in the award or admini

a contract supported by Federal funds if a confliet of interest, real or

apparent, would be involved. Such a conflict would arise when:

i The employee, officer or agent,

ii Any membet of his immediate family,

iii, His or her partner, or

iv, An organization which employs, or is about to employ, any of

the above, has a financial or other interest in the firm selected

for award.

20. Pursuant fo the 24 CF.R. 85, the HHA Executive Director is the

appropriate appointing authority for purposes of hiring of HHA employees, vendors and

independent contractors. Mayor Zimmer or Grossbard have no statutory authority to

interfere with the day-to-day operations of the HHA. Moreover, Mayor Zimmer is

prohibited from using her official position to influence the procurement process in order

to reward her political supporters through the award of government contracts and

‘employment opportunities.

21. Tn May 2012 and continuing to the present, Mayor Zimmer together with

Grossbard, conspired with Chairman Stuvier and other commissioners politically aligned

with Mayor Zimmer, have endeavor to use the HHA to implement Mayor Zimmer

unwritten political patronage policy.

22, Through her own appointment to the HHA and those made by

Hoboken’s City Couneil, which is made up of mostly Mayor Zimmer supporters, Mayor

Zimmer successfully orchestrated a majority voting block on the HHA Board that

effectively gave her control over the HHA. Despite her control and influence over the

HHA, Mayor Zimmer's efforts to implement her patronage policy she required Director

Garcia’s cooperation, whether voluntarily or coereed.

23. Mayor Zimmer needed Director Garcia’s cooperation to implement

Mayor Zimmer's political patronage policy. For example, Mayor Zimmer's could not

award HHA government contracts to her political supporters without Director Garcia's

cooperation since state law prohibits such political influence in the procurement process.

24, Mayor Zimmer also needed Director Garcia's cooperation to implement

Mayor Zimmer's version of Vision 20/20 and transform Hoboken into a white haven for

affluent white residents or members of the “New Guard.” Mayor Zimmer wanted to

implement a redevelopment plan to replace affordable housing with market-rate housing.

Under such a market-based housing initiative, members of the “Old Guard,” mostly low

income minority residents, would be forced to leave Hoboken because of its expensive

real estate market.

25. As with Mayor Zimmer's political patronage policy, Director Garcia

cooperation was paramount to implement Mayor Zimmer's redevelopment initiative

under the Vision 20/20 plan,

26. In May 2012, Mayor Zimmer contacted Director Garcia to secure his

political support to implement her policies in HHA. In substance Mayor Zimmer told

Director Garcia that she wanted his support to carry out her policies in HHA. Initially,

Mayor Zimmer told Director Garcia to tell the then HHA Chairwoman Rodriguez, a

Hispanic woman, to step down because she was not implementing Mayor Zimmer’s

political agenda. According to her, Mayor Zimmer considered Chairman Rodriguez?

failure to carry out her policies in the HHA to be tantamount to an act of disloyalty.

Mayor Zimmer told Director Garcia to instruct Chairwoman Rodriguez to step down as

HHA Chairman and make room for Stuvier, who was Mayor Zimmer's political

supporter and, thus, could be counted to execute Mayor Zimmer's policies in the HHA.

27. Given his tr

ining and experience, Director Garcia reasonably believed

that Mayor Zimmer’ instructions violated state and federal law, HUD and HHA

regulations, prohibiting political influence and patronage. Director Garcia objected to

Mayor Zi

nmet’s instructions because he considered it illegal and improper.

28. _ In response to Mayor Zimmer’s unlawful instruction, Director Garcia

not only refused to politically support Mayor Zimmer as an ally in HHA, but he flatly

refused to provide any assistance (o Mayor Zimmer to remove Chairwoman Rodriguez.

based on political reasons in violation of N.J.S.A. 40A:12A.

29. In the Summer of 2012, Mayor Zimmer and her political supporters on

the Hoboken City Council took control over the HHA. In furtherance of her political

patronage, Mayor Zimmer and Grossbard appointed Stuvier as HHA Chairman, and the

pro-Zimmer City Council appointed David Mello and Burrell on the HHA Board. These

commissioners were undeniably Mayor Zimmer political supporters and were seen as her

utter ego on HHA matters.

30. After becoming chairman in 2012, Chairman Stuvier admitted to

Director Garcia that Mayor Zimmer and HHA Commissioner Burrell were planning to

control the HHA by removing anyone that opposed Mayor Zimmer's policies in the

HHA. In that same conversation and in a threatening manner, Chairman Stuvier warned

Director Garcia that unless he politically supported Mayor Zimmer’s policies his

employment was at risk, Director Gareia interpreted Chairman Stuvier’s remarks to

constitute a direct threat {o his employment unless Director Garcia agreed to carry out

Mayor Zimmer's policies in the HHA.

31. When Director Garcia complained and refused to participate in Mayor

Zimmer's political patronage policy, Mayor Zimmer and Grossbard, through their

political allies on the IIIA, began to subject Director Garcia to an unlawful pattern of

harassment, threats, intimidation, and extortion in effort to coerce him to implementing

Mayor Zimmer's policies, such as awarding government contracts to her political

supporters and implementing her discriminatory version of Vision 20/20.

32. Director Garcia reasonably believed that Defendants’ attempt to

unlawful interference with and extortion of Director Garcia violated N.J.S.A. 2C:27-12,

the criminal statute involving “Corruption of a Public Resource.” Pursuant to N.J.S.A.

2C:27-12, a “public resource" means:

“any funds or property provided by the government, or a person acting on

behalf of the government... grants awarded by the government or an entity

acting on behalf of the government; and (7) credits that are applied by the

government against repayment, For purposes of this section, a purpose is

‘unauthorized if it is not the specified purpose or purposes for which a

Public resource is obligated to be used, and the government agency having

supervision of or jurisdiction over the person or public resource has not

given its approval for such use.”

33. Director Garcia, based on his training and experience as a HHA

executive director, reasonably believed that Mayor Zimmer and Grossbard, Chairman

Stuvier conduct violated Now Jersey criminal law. For example, an individual commits

the crime of “Corruption of a Public Resource,” under N.J.S.A. 2C:27-12 when:

“with respect to a public resource which is subject to an obligation to be

used for a specified purpose or purposes, the person knowingly uses or

makes disposition of that public resource or any portion thereof for an

unauthorized purpose.”

34, Afier the aforementioned threat to his employment, Director Garcia

reported Mayor Zimmer and Chairman Stuvier’s lawful scheme to the Housing and

Urban Development (“HUD”) and the Office of the Inspector General (“OIG”)

35, When Mayor Zimmer, Grossbard, and Chairman Stuvier learned of

Ditcetor Gareia's whistleblowing activities to HUD and O1G, Chairman Stuvier angrily

approached Director Garcia and, in a threatening manner, demanded to know “why

[Director Garcia] had contacted HUD and O1G.”

36. _Instead of stopping their unlawful scheme, the Defendants increased

their efforts to corrupt the HHA business affairs and procurement of government

contracts. On or about July 27, 2012, for example, Chairman Stuvier asked Executive

Director Garcia to meet for lunch, During that lunch meeting, Chairman Stuvier

demanded that Director Garcia “go after” a particular HHA resident and Hoboken City

‘Councilwoman Beth Mason because, as Chairman Stuvier explained, they were

considered political opponents of Mayor Zimmer. According to Chairman Stuvier: this

‘would ‘a test of your loyalty” to support Mayor Zimmer and her newly appointed HHA

board.

37. Again, Director Gareia objected and refused (o participate in such an

unlawful scheme and responded: “HHA should not be acting as an operative for the

mayor, nor should Zimmer, be imposing her political will on the HHA, as i

autonomous agency.”

38. Director Garcia further made it clear to Chairman Stuvier that he

objected to participating in any scheme to retaliate against anyone because of their

political beliefs or affiliation.

39. In July 2012, TTA contracts for general counsel were up for renewal.

Asa result, Director Garcia was required to oversee the bidding process to ensure that it

conform to HHA regulations. Director Garcia was prohibited by HHA regulations to

award a government contract based on political support to Mayor Zimmer.

10

40. During the selection process, Chairman Stuvier approached Director

Garcia with a directive from Mayor Zimmer to give the government contract to a

particular law firm, (“the Law Firm?) that was politically connected to Mayor Zimmer

and Grossbard. Specifically, Chairman Stuvier told Director Garcia that “Grossbard was

giving him orders as to what he needed from [Director Garcia] to do for Mayor Zimmer

in order to be in good standing so their people would back off (i.e. Mayor Zi

mer and

the politically aligned commissioners].”

4l Director Garcia reasonably believed that the appointment of Mayor

Zimmer's Law Fitm, based on political patronage, violated 24 C.F.R. 85.36 which

governs the procurement standards for the HHA and other laws prohibiting pay-to-play.

‘As result, Garcia objected and refused to participate. On or about August 10, 2012,

during a meeting with Commissioner Mello and Chairman Stuvier, Director Garcia

heard Grossbard called Chairman Stuvier over the telephone and instruct him to tell

Director Gari:

“Recommend Mayor Zi

mer’s choice for general counsel in order to

make [Garcia's] life easier.” Grossbard’s threat was extremely disturbing to Director

Garcia, given the blatant manner in which it was communicated to him through

Chairman Stuvier. The clear i

plication by Grossbard’s message was simple: unless

Director Garcia awarded the government contract to the Law Firm, in particular, and

plement Mayor Zimmer's policies, in general, there would be efforts to make his job

difficult to perform and, in effect, his job was at risk.

42 by the above communication because it suggested to that he was an

active participant in an illegal quid pro quo scheme to secure a government contract for a

political supporter of Mayor Zimmer—which he was not. Such a quid pro quo

arrangement is illegal and criminal. In response, Director Garcia then advised the HHA

board that he was contacting the OIG to report Mayor Zimmer and Grossbard’s corrupt

and unlawful efforts to control the HHA procurement process.

43. Because of Director Garcia’s failure to implement Mayor Zimmer's

unlawful patronage policies, the Defendants conspired to subject Director Garcia to a

hostile work environment, which included subjecting him to unfair and unreasonable

criticism, criticizing his work performance, creating extra and unnecessary work,

threatening his employment. ‘The object of the Defendants” hostile work environment is

‘o force Director Garcia's cooperation or involuntary resignation.

44, In this collective effort, the Defendants sought to unfairly and

excessively criticize Director Garcia by providing false or misleading information to

the media and bloggers friendly to Mayor Zimmer for the purpose of embarrassing and

humiliating him. In a particular, the website, Miles Square View, was employed by the

Defendants to disseminate falschood. As a proxy for Mayor Zimmer, the Miles Square

‘View published numerous articles designed to undermine Director Garcia manager

skills and embarrass him, and disrupt or interfere with the performance of his jab.

45. For example, during an October 2012 HHA open board meeting,

Chairman Stuvier approached a HITA (enant to encourage her to falsely accuse Director

Garcia of not adequately responding to her complaints regarding potentially hazardous

material inher apartment. The false aceusation would be used to accuse Director

Garvia of negligence and malfea

ince, thereby giving HHA the pretextual grounds to

terminate his employment.

12

46. On another occasion, Mayor Zimmer and Chairman Stuvier caused the

Hoboken Fire Chief to relay false information to the media in an effort to embarrass

Director Garcia, Mayor Zimmer also caused the Hoboken Building Department to issue

baseless summons to the HHA in a

lar effort to embarrass and humiliate Director

Garcia,

47. By deliberately interfering with Director Garcia’ duties, Chairman

Stuvier, Mayor Zimmer, and Grossbard unfairly blamed Director Garcia for not

performing his duties and not complying with HHA regulations.

48. In January 2013, after a several months of subjecting Director Garcia to

ahos

work environment, Grossbard scheduled a meeting in New York City, with

Director Garcia, along with a lawyer who served as an advisor to Mayor Zimmer.

49, ‘The purpose of the meeting was (o reaffirm what was made clear

previously by Mayor Zimmer, Grossbard, and Chairman Stuvier: if Director Garcia

implements Mayor Zimmer’s political patronage policies in HHA, his j

threaten,

50. At that meeting, Grossbard, who was apparently speaking on behalf of

Mayor Zimmer, warned

ctor Garcia that he was not the “HHA sole appointing

authority,” implying that he was not the only individual with power in the HHA to

appoint a Law Firm as general co

sel. In substance, Grossbard threatened Director

Garcia’s job by warning him that “if he [Garcia] wants to keep his job with the HHA, he

needs to go along with Mayor Zimmer’s policies and support her politically.”

1B

51 Director Garcia reasonably believed that Grossbard threat violated state

1 and criminal laws prohibiting quid pro quo and “pay-to-play” arraignments, such as

2C:27-12 , acriminal statute prohibiting the corruption of public resources.

52. Shortly after Director Garcia refused to support Mayor Zimmer, the

Defendants acting in concert with each other to punish Director Garcia sought to strip

him of his powers by creating a subordinate position, the Deputy Executive Consultant

position. The Deputy Executive Consultant Position was enacted to bypass Director

Gareia’s responsibilities to oversee the procurement policy so that Mayor Zimmer's

political supporters could win the government contract. In turn, by implementing such a

Position, the HHA Board and Chairman Stuvier, with hiring and firing power, could

‘appoint an individual politically aligned to Mayor Zimmer, who would blindly implement

her unlawful patronage policies.

53. Then in February 2013, Chairman Stuvier violated the procurement

policy and attempted to install a politically-connected Law Firm, which violated 24

CPR. 85.36,

54, In March 2013, Director Garcia complained to DCA and reported

Chairman Stuvier

untawfial attempt to procure the Law Firm politically aligned with

Mayor Zimmer in violation of 24 CPR. 85.36.

55. After Director Garcia reported Chairman Stuvier’s violation to the DCA,

Chairman Stuvier, working in concert with Mayor Zimmer, served Director Garcia with a

Rice Notice in retaliation, The purpose of the Rice Notice was a designed to actually to

terminate his employment contract without cause. Since Ditector Garcia was performing,

his duties and responsibilities in a satisfactory manner, the only reason why Chairman

Stuvier and other pro-

mmer HHA Commissioners approved the Rice Notice was to

signal intent to Director Gan

to either support Mayor Zimmer or his employment

would be terminated.

56. Although the Rice notice hearing was unsuccessful that evening, the

threat of the Director Garcia’s discharge was left opened, and still remains unresolved

causing extreme anxiety and stress to Director Garcia,

57. Because of Director Garcia’s whistleblowing , Mayor Zimmer and

‘Chairman Stuvier increased their retaliation of Director Garcia causing him to be

subjected to an abusive and hostile work environment, In response, Director Garcia

continued to object to Mayor Zimmer and Stuvier’s threats, which he reasonably believed

violate both civil and criminal state statues, namely, N.J.S.A. 40A-12A, and NLS.A.

2C:27-12,

58. Inresponse to Defendants’ efforts to force his cooperation and Jor

involuntary resignation based on his failure to participate in implementing Mayor

Zimmer's unlawful political patronage policy, Director Garcia repeatedly “blew the

whistle” and otherwise expressed his freedom of speech under the New Jersey

Constitution to complain about the Defendants’ unlawfill activities to HUD , the OIG and

HHA. For example, Director Garcia blew the whistle and engaged in constitutionally

protected activities as follows

a In August and September 2012, Director Garcia filed a

written complaint to HUD, HHA, and the Department of Community

Affairs (“DCA”) regarding Mayor Zimmer, Chairman Stuvier, and

15

Commissioner Melos’ unlawful threats and corruption efforts in the HHA

procurement process.

b. In February 2013, Director Garcia contacted a third part

professional with knowledge of the HHA, and obtained his professional

opinion as to the current “unlawful political climate of the HHA.” In turn,

this third-party, professional rendered the opinion to Director Garcia that

if he did not follow Mayor Zimmer’s scheme to procure politically aligned

firms, and implement her version of Vision 20/20, she would hold him and

the HHA “hostage” and continue to subject Director Garcia to harassment

c. In March 2013, Director Garcia made appointments to meet

with agents and officers of the OIG in-person to blow the whistle on

Mayor Zimmer’s scheme to corrupt the HHA procurement process and

business affairs through her political patronage policy.

d, In July 2012, Executive Director Garcia complained to

‘Chairman Stuvier that it was wrong and illegal to implement Mayor

Zimmer's policies pursuant to HUD regulations, N.J.S.A. 40A:12A-17, on

the selection and awarding of a contract to a law firm not vetted or ranked

most advantageous by the Executive Director and committee, Director

Garcia advised that his employment should not and could not be used as a

tool to force his loyalty against publie mandate or process.

€. In June 2013, Director Garcia blew the whistle on Mayor

‘Zimmer and Chairman Stuvier’s unlawful conduct to the Hudson County

Prosecutor’s Office because he reasonably believed the conduct to be

16

criminal. Director Garcia contacted the Hudson County Prosecutor's

Office via official leter.

£. In August 2013, Director Garcia repeatedly contacted his

superiors at HUD to report Mayor Zimmer and Chairman Stuvier and

‘Commissioner Mello’s continuous harassment of him via letters and

emails.

59. The aforementioned whistleblowing activities were known to the

Defendants, In response to Director Garcia’s complaint, Chairman Stuvier,

‘Commissioner Mello, and Mayor Zimmer continued to subject him to a hostile work

environment by subjecting him to continuous threats to his employment, unfair criticism

of his work performance, enhanced work assignments, and excessive monitoring of his

work, subjecting HHA to selective enforcement by Hoboken government officials from

the police department, fire department, and building inspectors, The object of the

harassment is to force Director Garcia to capitulate or fubricate a pretextual ground to

terminate his employment contract.

60. Director Garcia’s work performance was never criticized by prior to his

opposition to Mayor Zimmer’s illegal political patronage poliey.

61. Due to the aforementioned unlawful and retaliatory actions taken by

Mayor Zimmer and Stuvier in his role as HHA Director, Garcia has been subjected to.a

hostile work environment by their obstruction with the regular business of the HHA and

continuously harassing him to conform with their unlawful policies because of his

whistleblowing—not because of his work performance,

wv

62. Because of his failure to cooperate with Mayor Zimmer, Grossbard, and

Chairman Stuvier’s conspiracy to implemented Mayor Zimmer's unwritten and

unconstitutional political patronage policy, Executive Director Garcia was and continues

to be subjected to a hostile work environment, including but not limited to: frequent

threats, extortion, intimidation, defamatory statements about his professional abilities

through intemet websites and bloggers friendly to Mayor Zimmer, unfair criticism of his

work performance, continuous threats to his employment, and other tangible and

intangible adverse employment activities. As a result of the hostile work environment,

Director Garcia's em

nal distress and anxiety has increased to a dangerous level,

which affect his daily activities, work performance, relationship with his family, and his,

health by being placed on medication due to the stress, anxieties, and sleep deprivation,

63. Despite Director Garcia numerous complaints to HHA and other

governmental agencies about the Mayor Zimtner’s unlawful retaliation and political

interference with the HHA, and violation of civil and criminal laws, no corrective actions

were taken.

1

COUNT ONE

CONSCIENTIOUS EMPLOYEE PROTECTION ACT (CEPA)

N.J.S.A 34:19-3 ef seq

HHA, Mayor Zimmer, Commissioner Stuvier

64, All of the allegations in cach of the foregoing paragraphs are

incorporated by reference as if fully set foxth herein,

65. Defendants are Plaintiff's employer for purposes of CEPA. Defendant

Chairman Stuvier, exercises control over Plaintifi’s terms and conditions of his

18

employment, Mayor Zimmer is a joint-employer because she engaged in a conspiracy

with HHA Commissioner Stuvier.

66. Defendants retaliated against the Plaintiff after he objected to and

refused to participate in various unlawful activities that reasonably violated civil and

criminal laws; namely, N.J.S.A, 40A:12A-17, and 2C:27-12.

67. Plaintiff's protected activities are not covered by his employment

contract or part of his duties and responsibilities.

68. Defendants actions violate New Jersey Conscientious Employee

Protection Act, N.J.S.A 34:19-3 ef seq. and have caused Plaintiff'to suffer economic,

emotional, and psychological damages in an amount to be determined by a jury.

WHEREFORE, the Plaintiff demands judgment against the Defendants, jointly

and severally, for the following relief:

a. Compensatory Damages;

b. Punitive Damages;

¢. Attorney's fee and cosis of suit;

d. Such other and further relief that the Court deems equitable and just.

i.

COUNT TWO

NEW JERSEY CIVIL RIGHTS ACT

Nd.S.A. 10:6-2

69. All of the allegations in each of the foregoing paragraphs are

incorporated by reference as if fully set forth herein,

19

70 Pursuant to official policy, custom, and practice, Defendant Mayor

Zimmer, Chairman Stuvier, HHA, acting under color of law, have lawfully subjected

Plaintiff to a hostile work environment substantially motivated because of the exercise of

his constitutionally protected activities under New Jersey's Constitution, Article 1,

Sections 6 and 18, namely the right to be free from any political affiliation and freedom

to express one’s political views, opinions and sentiments to one’s governmental

representatives without fear of retribution.

71. Grossbard is a state actor for purposes of enforcing Plaintiff's

constitutional rights herein based on his affirmative participation in and conspiracy with

Mayor Zimmer and Chairman Stuvier to deprive Director Garcia of his constitutional

rights secured under the New Jersey Ci

stitution.

n Pursuant to official policy, custom, and practice, HHA, Chairman

Stuvier, Grossbard, and Mayor Zimmer unlawfully retaliated against Plaintiff because of

his lack of political support for Defendant Mayor Zimmer by creating a hostile work

environment.

B Plaintif?’s constitutionally protected activities, as alleged herein, were

the motivating factor for Defendants retaliatory conduct,

" Defendants? pattern of retaliatory conduct, which has caused a hostile

work environment to exist in HHA, has caused a chilling effect to Plaintiff and other

employees who may desire to engage in such protected activities.

75. Alternatively, those Defendants who could have stopped the unlawful

violations of Plaintiff's civil rights are liable based on their failure to intervene to stop the

said civil rights violations.

20

76. As adirect and proximate cause of the aforementioned retaliatory

conduct, Plaintiff has suffered and will continue to suffer economic, emotional, and

psychological damages in an amount to be determined by a jury, Because of Defendants

Mayor Zimmer, Grossbard, and Chairman Stuviers? willful and malicious conduct,

Plaintiff seeks punitive damages in their individual capacity in an amount to be

determined by a jury.

WHER]

FORE, the Plaintiff demands judgment against the Defendants, jointly

and severally, for the following relief:

‘Compensatory Damages;

b, Punitive Damages only as to the named individual defendants

c., Altorney’s fee and costs of suit;

4. Such other and further relief that the Court deems equitable and just

u

COUNT THREE,

TORTIOUS INTERFERENCE WITH

CONTRACTUAL RELATIONS.

GROSSBARD

1. llegations in each of the foregoing paragraphs are

incorporated

78. Inhis unofficial capacity as Mayor Zimmer's political adviser,

commencing on or about June 2012 and continuing to the present date, Grossbard and the

Defendants used his special relations with Mayor Zimmer to unlawfully interfere with,

obstruct and/or undermine Plaintiffs’ contractual relations with HHA.

21

79, Gross bard’s continuous and tortious interference with Plaintiff's

business

relations with HHA were designed to cause economic harm to his employment contract

and future opportunities.

80. Grossbard’s conduct was retaliatory and without a legitimate purpose,

and was intended to interfere with, impair, and destroy Plaintiff’s contractual

telationships.Plaintiffs’ contractual relationships gave rise to a reasonable expectancy of

economic gain on the part of the plaintfts.

81. Deftndant’s actions were unjustified, unreasonable, and

intended to interfere with Plaintiffs’ ability to conduct their legitimate business affairs.

82, As a direct and proximate result of Defendant's actions, Plaintiff has

suffered economic and emotional damages in an amount to be determined by a jury,

WHEREFORE, Plaintiff démands judgment against Defendant for the following:

a. Compensatory damages in an amount to be determined by a jury;

b, Interest from the date of entry of judgment at a rate of percent per annum;

c. Punitive damages;

4. Costs of suit; and

Any other and further relief that the court considers proper.

Vv.

COUNT FOUR

TORTIOUS INTERFERENCE WITH

PROSPECTIVE ECONOMIC ADVANTAGE

83. _Plaintiff repeat and reallege the allegations set forth above as if fully set

forth herein,

22

84. Commencing on or about June 2012 and continuing to the present date,

85, Grossbard using his special political relationship with Mayor Zimmer,

unlawfully interfered with, obstruct and/or undermine Plaintiffs’ contractual relations

with HHA,

86. Plaintiff had business relationship with bona fide third party, namely the

HHA,

87. Plaintiff?’ business relationship gave rise to a reasonable expectancy of

economic gain,

88. Defendant Grossbard engaged in the aforementioned conduct that

interfered with that business relationship, namely that HELA has served Plaintiff with Rice

Notice which remains open and subject to HHA action, Defendant Grossbard

deliberately and

fully intended the conduct to result in the impairment or destruction

of the aforenientioned business relationship.

89. Defendant's conduct was the proximate cause of the loss or impairment

of the Plaintiff's prospective economic advantages,

90, Defendant's aetions were unjustified, unreasonable, and intended to

interfere with Plaintiffs’ ability to conduet their legitimate business affairs,

91. Asadirect and proximate result of defendant's actions, plaintiff suffered

economic and emotional damages in an amount to be determined by a jury.

WHEREFORE, Plaintiff demands judgment against Defendant Grossbard for the

following:

a. Compensatory damages in an amount to be determined by a jury;

b. Interest from the date of entry of judgment at a rate of percent per annum;

23

¢, Punitive damages;

4. Costs of suit; and

e. Any other and further relief that the court considers proper

92. Plaintiff repeats and realleges the allegations set forth above as if fully

set forth herein,

93. Asa Puerto Rican, Plaintiff was discriminated on the basis of his

ethnicity and race by his Defendants Mayor Zimmer employer HHA and Chairman

Stuvier.

94. Defendant HHA discriminated against the Plaintiff in the terms and

conditions of his employment by subjecting him to a hostile work environment that was

pervasive and/or severe as alleged herein,

95. Defendant actions were taken in violation of New Jersey Law Against

Discrimination, N.J.S.A. 0:5-1 ct seq. and have caused Plaintiff to suffer economic,

emotional and psychological damages in an amount to be determined by a jury.

WHEREFORE, the Pl

‘demands judgment against the Defendant HHA for

the following relief:

a. Compensatory Damages;

b. Punitive Damages, including treble damages;

©. Attomey’s fee and costs of suit;

4, Such other and further relief that the Court deems equitable and just.

24

UNT SIX

New Jersey Law Against Discrimination

No.S.A. 10:5-1

ding and Abetting

Mayor Zimmer, Grossbard and Chairman Stu

96. Plaintiff repeats and realleges the allegations set forth above as if fully

set forth herein,

91, Atalll times, Defendant Mayor Zimmer, Grossbard and Chairman

Stuvier conspired with each other to violated Plaintiff's rights to be free from unlawful

discrimination under NJLAD. In their official and unofficial capacities, Defendants

knew or should have known state and federal laws against discrimination on the basis of

ethnic and race.

98. Defendants conspired with each to subject Plaintiff to a hostile work

environment on the basis of his ethnicity and race as alleged herein.

99, Defendants provided substantial assistance to HHA to carry out its

unlawful discriminatory scheme against Plaintiff because of his ethnicity and race in

violation of state anti-discrimination laws prohibiting a hostile work environment on the

basis of ethnicity and race.

100. ‘The actions of Defendants violate New Jersey's Law Against

Discrimination, N.J.S.A. 10:5-1, ef seq., and have caused Plaintiff to suffer economic and

emotional damages in an amount to be determined by a jury

WHEREFORE, Plaintiff demands judgment against Defendants for the following:

4, Compensatory damages in an amount to be determined by a jury;

b. Interest from the date of entry of judgment at a rate of percent per annum;

¢. Punitive damages;

25

4. Costs of suit; and

¢e, Any other and further relief that the court considers proper.

DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL

Plaintiff hereby demands a trial jury as to all |

DATED: January 23, 2014

DESIGNATION OF TRIAL COUNSEL

LOUIS A. ZAYAS, ESQ,, is designated as trial counsel in this matter.

DATED: January 23, 2014

LOUIS'A, ZAYAS, ESQ.

DEMAND FOR PRODUCTION OF INSURANCE Ai

MI

Pursuant to R. 4:10-2(b), demand is hereby made that you disclose to the

undersigned whether there are any insurance agreements or policies under which any

person or firm carrying on an insurance bu

ess may be liable to satisfy all or part of a

judgment which may be entered in the action or to indemnify or reimburse for payment

made to satisfy the judgment. If so, please attach a copy of each, or alternative state,

under oath and certification: (a) policy number, (b) name and address of insurer; (c)

inception and expiration dated; (d) names and addresses of all persons insured there

under; (e) personal injury limits; (f) property damage limits; and (g) medical payment

26

DATED: January 23, 2014

27

EXHIBIT 1

34

KROVATIN KLINGEMAN, LLC WEL 2083

60 Park Place, Suite 1100 oes

Newark, New Jersey 07102 see ee

P (973) 424-9777 LAWRENCE WARUS, JS.0,

Attorneys for Defendant Mayor Dawn Zimmer

: SUPERIOR COURT OF NEW JERSEY

CARMELO GARCIA, LAW DIVISION:

: HUDSON COUNTY

Plaintiff,

DOCKET NO. HUD-L-3818-13

v.

CIVIL ACTION

DAWN ZIMMER, in her Official and

Individual Capacity a3 Mayor of :

Hoboken, HOBOKEN HOUSING ORDER OF DISMISSAL

AUTHORITY, JAKE STUVIER, in his

Official and Individual Capacity as

Housing Authority Chairman, and:

STAN GROSSBARD

Defendants, _

THIS MATTER having been opened to the Court by Krovatin Klingema LLC,

stlomeys for defendant Mayor Zimmer for an order dismissing the Complaint in this action, on

Totiee to Louis Zayas, allomey for Plaintiff, and the Court having considered the papers filed on

behalf ofthe parties, and the arguments of counsel, and for good cause shown,

lay of DBecern\oes__, 2013, ORDERED:

DEtLD erthay Hey vhoe

1 Defendant Mayor Zimmer's Motion is hereby -GRSRREBS Get

TTS on thi

omplaintinsieamer tesa DISWISSED SMe

2. A copy of this Order shall be served on all counsel by counsel for

efendant Mayor Zimmer within 7 days of receipt of this Oxler.

Desed totrove Prqvsiee. IL

TA Plewerds dors Nor mart sae

IS.C.

wArend wetwin Bs dey 5 Ob = WRENCE M, MARON, 2.5

Te Cccber the Comyplesunty er -te Lensons Sor Forth in the

AS te Maye Zummer, os +t Attached Findsngs ob Fitet end

Petams te CePA and MSCEH Conclusions ot cod,

Chums Chath be Bismesed-

S4/5-

FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

Gari

Docket: 1.-3818-13

Motion Returnable: 12/6/13

Relief Requested: Defendants, Hoboken How

Dismiss (Control #19)

ing Authority and Jake Stuvier’s Motion to

Defendant, Mayor Dawn Zimmer’s Motion to Dismis

(Control #20)

AC

‘The facts and allegations as presented by Plaintiff, and which must be assumed as true for the

purposes of this motion, see R. 4:6-2(e), are as follows:

‘+ Plaintiff, Carmelo Garcia, is the Executive Direefor of the Hoboken Housing Authority

(lousing Authority).

© Plaintiff has a five-year contract

+ Inhis complaint, Plaintiff refers to himself as a “Hispanic citizen of New Jersey.”

* By virtue of his position, Plaintiff is responsible for overseeing the day-to-day operations

of the Housing Authority, including hiring employees, vendors and independent

contractors

‘+ The Housing Authority is an independent authority created pursuant to N,LS.A

40A:12A-I ef sea, to oversee federally subsidized, low-income housing within Hoboken.

‘+ The Housing Authority is governed by a seven member hoard. The Governor and Mayor

‘each appoint one Commissioner. ‘The City Council appoints the other 5 Commis

‘© Plaintiff asserts that Defendant, Mr. Jake Stuvier!, a Commissioner of the Board of the

Housing Authority, sought (o have Mr. Gatcia make changes at the Housing Authority to

conform te Defendant, Mayor Dawn Zimmer's poliey objectives.

* The Complaint states that Mr. Stuvier and Mayor Zimmer are “white.”

+ On May 8, 2012, Mayor Zimmer contacted Plaintiff, She asked him to help her remove

Chairwoman Jeanne Rodriguez, support her policies and also support Mr. Stuvier’s

candidacy for Board Chair. Plaintiff refused.

+ Affer that incident, Mayor Zimmer again contacted Plaintiff and asked him to support her

policies. She indicated that he could remain in his position if he did so, Plaintiff refused.

+ Inresponse, Plaintiff alleges that Mayor Zimmer told Mr. Stuvier to “harass” Plaintiff's

‘work performance.

joners.

2 har dake Stuer

the sake of clarity,

properly pled as Mr. Jake Stuvier, The Court willuse the name as spelled in the caption for

Chairwoman Rodriguez. was replaced by Mr. Stuvier in July, 2012. Plaintiffalleges that

Mayor Zimmer, through political maneuvering, appointed Mr. Stuvier Chairman of the

Board of the Housing Authority and thereby obtained effective control of the Housing

Authority,

On July 27, 2012, Mr. Stuvier had lunch with Plaintiff and allegedly asked him to “go

afer” a Housing Authority tenant, City Council member, Beth Mason. Plaintiff refused

Jn July 2012, Mr. Stuvier, at the request of Mayor Zimmer, allegedly requested that

Plaintiff award a public contract to a particular law firm, Plaintiff refused,

Plaintiff alleges that Mayor Zimmer, and others, either “plotted to create a hostile work

environment” to force Plaintiff's resignation or to find grounds to terminate him,

Mr, Stuvier sought to create a Deputy Executive Director of the Housing Authority. That

measure was defeated

Mr. Stuvier also served Plaintiff with a Rice notice, indicating that his employment status

may be diseussed at a Board meeting, but no such discussion took place.

© Mr, Garcia alleges that he prevented the discussion,

Plaintiff claims that these incidents

a hostile work environment.

‘The Chief of the Hoboken Fite Department attended a public meeting of the Housing

Authority to embarrass Plaintiff “with false information about how he was handling

restoration” after Hurricane Sandy.

ised him emotional distress and effectively ereated

Plaintiff asserts that he is subject to “fiequent threats, extortion, intimidation, defamatory

statements about his professional abilities. unfair criticism of his work performance,

continuous threats to his employment, and other tangible and intangible adverse

employment activities.”

Plaintiff asserts that Mayor Zimmer’ s

ind Mr, Stuvier's goal, replacing the “old guard”

of Hoboken residents who are minorities with white upwardly mobile citizens, amounts

toa policy of “ethnic cleansing.”

Plaintiff brings actions against Defendants asserting claims under the New Jersey

Conscientious Employee Protection Act (CEPA), N.J.S.A. 34:19-3 et seq., and the New

Jersey Civil Rights Act (NICRA), N.LS.A. 10:6-1 et. sea.

MOVANTS’ ARGUMENTS.

Even if PlaintifF’s allegations are presumed to be true, he fails to state a claim for which

relief can be granted.

As to Mayor Zimmer:

© Mayor Zimmer is not Plaintiff's employer under CEPA and the claim is not

viable.

© Plaintiff's alleged injuries are not actionable under CEPA.

© The retaliation alleged is de minhmmus and is not an adverse employment action

sufficient to support a claim under the NICRA.

+ Asto the Housing Authority and Mr. Stuvier:

‘© There were no violations of law, rule, regulation or public policy,

© There was no adverse employment action.

© CEPA requites Plaintiff to waive any parallel claims.

(© Plaintiff's free speech rights were not infringed

+ Plaintiff's right to free speech may be limited by his position as a public

employee.

+ The retaliation was not of a constitutional magnitude.

OPPOSITION ARGUMENTS

* Mayor Zimmer is a *joint employer” of Plaintiff.

+ Plaintiff has pled an adverse employment action,

+ Defendants’ arguments are “frivolous” and “wholly meritless”.

+ Plaintiff has stated a cognizable claim under the NICRA.

REPLY ARGUMENTS,

* Plaintiff's CEPA claim is deficient because he did not reasonably believe that his

employer's conduct was violating either a law, rule, or regulation promulgated pursuant

to law, ora clear mandate of public policy

‘+ Plaintiff's NICRA claim is deficient because there was no chilling effect on Plaintiff's

speech, which was qualified by his position

‘+ There was no adverse employment action,

Mayor Zimmer is not a “joint employer”

© A CEPA claim waives the NICRA claim,

ANALYSIS

1 Procedural History

Defendant, Mayor dawn Zimmer (“Mayor Zimmer”), filed a motion to dismiss, which was

originally returnable October 11, 2013. On October 2, 2013, Plaintiff requested a one-cycle

adjournment, to October 25, 2013, to submit opposition papers. That request was granted with

the consent of Mayor Zimmer's counsel,

On October 3, 2013, Co-Defendants, the Hoboken Housing Authority (“Housing Authority”)

and Mr. Jake Stuvier (“Mr. Stuvier"), requested that the Court adjourn Mayor Zimmer's motion

to November 22, 2013, when their motion to dismiss was intended to be returnable. All counsel

consented to this adjournment. The Court granted the adjourment request for Mayor Zimmer’s

motion. Co-Defendants timely filed their motion and both were scheduled to be heard on

November 22, 2013.

Gn November 13, 2013, PlaintifP’s counsel wrote to the Court fo request an adjoumment of

all motions to December 6, 2013, Counsel’s letter represented that this was the first adjoummment

request made on behalf of his client. Although it was actually Plaintiff's second adjournment

request, all counse! consented to the December 6, 2013 date,

Despite the lengthy delay in hearing Mayor Zimmer's motion, for the sake of judicial

economy and to prevent duplicative oral argument, the Court granted the adjoumnment request.

The motions were, therefore, rescheduled for December 6, 2013,

On December 3, 2013, Plaintiff's Counsel submitted his opposition briefs. The oppositions

were untimely. Consequently, Defendants contacted the Court and requested an adjournment

until December 20, 2013, so as to have time to submit reply briefs, PlaintifPs counsel did not

object

Therefore, the motions were, once again, rescheduled. Both motions were made retumable on

December 20, 2013. Defendants’ counsel were informed that their reply papers were due

December 11, 2013.

I. Standard of Review

The

“ourt, on a motion to dis

niss for failure to state a claim, must determine “whether a

cause of action is ‘suggested’ by the facts" alleged, Printing Mart-Morri

116 NJ. 739, 746 (1989) (citing Velantzas v. Colgate-Pal

(1988)). ‘The Court’s “inquiry is ts

arp _Elees.

10, 109 N.J. 189, 192

ited to examining the legal sufficiency of the facts alleged

47, $52

(App. Div. 1987)). Thus, "a reviewing court ‘searches the complaint in depth and with liberality

nolive |

on the face of the complaint." Ibi

citing Rieder v. Dept. of Transp., 221 N.J. Super.

to ascertain whether the fundament of a cause of action may be gleaned even from an obscure

statement of claim, opportunity being given to amend if necessary.” Ibid.

x. Laurel Grove Memorial Park, 43 N.J. Super. 244, 252 (App. Div. 1957). At this stage of the

jgation, the Court does not focus on the plaintiffs ability to prove the allegations in the

complaint. Ibid, (citing Somers Constr. Co. v. Board of Educ,, 198 F. Supp. 732, 734 (DN.

1961)), Instead, plaintiff is "entitled to every reasonable inference of fact." Ibid, (citing Indep.

Dairy Workers Union v. Milk Drivers Local 680, 23 NJ. 85, 89 (195). As such, “[i]f a

generous reading of the allegations merely suggests a cause of action, the complaint will

SBC Communs., Inc,, 178 N.J. 265, 282 (2004) (quoting E.G.

y.MaeDonell, 150 N.J. 550, 556 (1997)) (alteration in original). The motion is granted only

withstand the motion." Smith

n

rare instances and ordinarily without prejudi

546 (2007).

. See In xe Contest of November 8, 2005, 192 N.J.

Because the Court will not consider any documents beyond the pleadings, this

:6-2(e),

motion will

not be treated as a motion for summary judgment, See R.

HL Mayor Zimmer's Motion

Two Counts of Plaintiff's complaint pertain to Mayor Zimmer. Those Counts allege

violations of CEPA and the NJORA. These allegations are addressed in turn,

A. CEPA

It is well settled that CEPA is designed to "prevent retaliation against those employces

‘who object to employer conduct that they reasonably believe to be unlawful or indisputably

dangerous to the public health, safety or welfare." Meblamn v, Mobil Qil Corp., 153 NJ. 163,

193-94 (1998); see also NLILS.A. 34:19-3. "[T]he offensive activity must pose a threat of public

harm, not merely private harm or harm only to the aggrieved employee.

Mebiman, supra, 153

NJ. at 188, To establish a cognizable CEPA claim, an employee must show that:

(1)he or she reasonably believed that his or her employer's conduct

was violating either a law, rule, oF regulation promulgated pursuant

to law, or a clear mandate of public policy;

(2) he or she performed a "whistle-blowin;

NULS.A. 34:19-3(0);

activity described in

G) an adverse employment action was taken against him or her;

and

(4) a causal connection exists between the whistle-blowing

activity and the adverse employment action

Dzwonar v. MeDevitt, 17 N.L. 451, 462 (2003)

The first prong of the test requires that the employee held a reasonable belief of conduct

that is either illegal or violates a clear mandate of public policy. ‘There is no clear indicati

nin

the complaint of what law, rule or regulation Plaintiff believed was being violated. It is also

tmclear what conduct or activity engaged in by Mayor 2

immer was injurious to the public, rather

than a personal harm to Plaintiff alone, See Mehiman, supra. The faets, as pled, and construed

generously in favor of the Plaintiff, together with all reasonable inferences, state that Mayor

Zimmer and her administration attempted to secure Plaintiff's assistance

implementing the

Mayor's policy agenda. Plaintiff does not provide any legal support for the argument that

political maneuvering in an attempt to advance new policies or initiatives of a duly elected

official is a threat to the public interest,

Plaintis? does not allege that the Mayor's agenda itself was illegal or a violation of public

policy. Nor has Plaintiff provided any support for the argument that either attempting to change

the composition of an appointed body or seeking to attract a new population to the City is illegal

Moreover, Plaintiff does not provide any legal authority fo show this Court how the Mayor?s

policy agenda or her attempt to implemedt it are illegal, inappropriate or injurious to the public.

For those reasons, Plaintiff fails to state a claim as

matter of law as there was nothing in

the motion record to demonstiate conduct for which Plaintisf could “blow the whistle” and

present an actionable claim under CEPA.

Mayor Zimmer also contends that Plaintiff's claim fails because she is not his employer

NLLSA. 34:19-2 defines employer as an “individual, partnership, association, corporation or any

person or group of persons acting directly or indirectly on behalf of or on in the interest of a

employer with the employer’s consent. . .." The statue provides that governmental agencies and

political subdivisions are employers. NJ.S.A. 34:19-2, An “employer” is anyone “with the

power and responsibility to hire, promote, reinstate, provide back pay and take other remedial

action.” Abbamont v. Piscataway ‘Twp. Bd, Of Educ, 138 N.J. 405, 418 (1994).

Plaintiff argues that Mayor Zimmer is his “joint employer.” Plaintiff urges the Court to

consider the “economic reality rather than technical concepts.” See In Re Enterprise Rent-A-Car

Hour Employment Prectices Litie., 683 F.3d 462, 467-68 (3d. Cit. 2012). Plaintiff

argues that the Third Circuit approach, namely the “significant control” test should apply. That

test considers, as non-exhaustive factors, 1) authority to hire and fire 2) authority to promulgate

work rules and as

jgnments and set conditions of employment, including compensation, benefits,

and hours; 3) day-to-day supervision, including employee discipline; and 4)control of employee

records. Pla’s Br. at 8 (citing Enterprise Rent-A-Car, 683 F.3d at 468-69).

Plaintiff also argues that this Court could apply a “totality of the circumstances test" as

applied in Hoag vy. Brown, 397 N.J. Super. 34 (App. Div. 2007). Hoag concemed a “non-

traditional employment relationship”, where the individual bringing a Law Against

Discrimination claim was the employee of an agency and was then assigned to correctional

facility to complete her employment duties. The factors articulated by the Court were:

(1) the employer's right to contro! the means and manner of the

worker's performance; (2) the kind of occupation~supervised or

unsupervised; (3) skill; (4) who furnishes the equipment and

workplace; (5) the length of time in which the individual has

worked; (6) the method of payment; (7) the manner of termination

of the work relationship; (8) whether there is annual leaves (9)

whether the work is an integral part of the business of the

“employer;" (10) whether the worker accrues retirement benefits;

(11) whether the "employer" pays social security taxes; and (12)

the intention of the parties,

Od, at 48]

Plaintiff alleg

that Mayor Zimmer “sought to control” the Housing Authority and

“sought to implement” her vision of HHA 20/20. Plaintiff also alleges that Mayor Zimmer

“continued to harass Director Garcia.” Even accepting the facts of the complaint as tne and

applying the liberal standard applicable to this motion, none of these allegations suffices to show

any employment relationship or actual control by Mayor Zimmer.

If the Court were to accept Pla

‘iff's argument and apply the Third Circuit test, the facts

pled show thet Mayor Zimmer could not hire, fire, discipline, supervise or control Plaintiff. That

action could only be taken by the Board of the Housing Authority. Mayor Zimmer only appoints,

one (1) member of the seven (7) member Board. Therefore, the Third Circuit test is unavailing

‘The test articulated in Hoag is also inapplicable to this case. ‘That test is used to provide

Protection where plaintiffs are “contracted out” to a third party to perform a task for the third

party. Here, Plaintiff's employment contract is with the Housing Authority and that is the only

entity for which he works, Therefore, the Hoag testis inapplicable to the facts of this case.

‘The facts, as presented by Plaintiff and afforded all reasonable inferences, as required by

Printing Mart, supra, show that Mayor Zimmer is not an employee or agent acting on behalf of

‘he Housing Authority. Mayor Zimmer does not have the power to hite, fire, remunerate or take

action against Plaintif? in his capacity as Executive Director of the Housing Authority. Mayor

Zimmer, as stated in Plaintiff's complaint, only has the authority to appoint a single

Commissioner to the Housing Authority Board. Mayor Zimmer cannot control Plaintiff, as the

facts of the complaint make clear, As such, no definition of “employer” accepted by the courts of

this State, our Legislature, or the Third Cireuit is presented to this Court that would classify

Mayor Zimmer as Plaintiff's employer and, consequently, the CEPA claim against her is not

viable.

Even if Mayor Zimmer were somehow to be considered as Plaintif?’s employer, Mayor

‘Zimmer asserts that there has been no actionable adverse employment action under CEPA.

Plaintiff correctly argues that the phrase “or other adverse employment aetion, .." should

be construed liberally “to deter workplace reprisals against an employee speaking out against a

company's illicit or unethical activities.” Donelson v. DuPont Chambers Works, 206 NJ. 243,

257-58 (2011). However, that standard does not undercut the precedent that applies to situations

such as the one presented by this case.

CEPA de!

1es “retaliatory action” as any “discharge, suspension or demotion, . .or other

adverse employment action taken against an employee in the terms and conditions of

employment.” N.J.S.A. 34:19-2(¢). “New Jersey Court have interpreted N.J.S.A. 34:19-2(e) as

requiring an employer’s action to have either impacted on the employee’s compensation or rank

‘or be virtually equivalent to discharge in order to give rise to the level of retaliatory action

required for a CEPA claim.” Klein v. Univ, of Med, & Dentistry of N.J., 377 NJ. Super. 28, 46

(App. Div, 2005); Caver v. City of Trenton, 420 F.3d. 243, 255 (3d. Cir. 2005). “[RJetaliatory

action does not encompass action taken to effectuate the discharge, suspension, or demotion but

rather speaks in terms of completed action . . . Nor does the imposition of a con

ion on

continued performance of duties in and of itself constitute an adverse employment action as a

matter of law, absent evidence of adverse consequences flowing from that condition.” Caver,

supra, 420 F.3d at 255 (quoting Klein, supra, at 46).

Our Courts have noted that CEPA claims are not viable where the terms and conditions

of Plaintiff's employment have not been altered, see Beasley v. Passaic County, 377 N.J. Super.

585, 608 (App. Div, 2005), or the conditions of Plaintiff's work have not been materially altered.

‘See El-Sioufi v. St, Peter's Univ. Hosp., 382 N.J. Super. 145, 176 (App. Div. 2005). Moreover, a

plaintifPs mere dissatisfaction with his employment is not actionable, See Cokus_v. Bristol

Myers-Squibb Co,, 362 N.J. Super. 366, 378 (Ch. Div, 2002) aff'd, 362 N.J. Super. 245 (App.

Div. 2003).

Defendant cites Kadetsky v. Fee Harbor Twp. Bd. Of Educ,, 82 F. Supp. 2d 327, 340

(D.N.J. 2000), and Whistleblower 1 v, Bd. Of Fdue. Of City of Elizabeth, N.J., 2011 U.S. Dist.

LEXIS 135203 (D. N.J. 2011), for the proposition that harassment alone is not actionable under

CEPA. Defendant further asserts that alleged emotional distress is insufficient to state a elaim

under CEPA, See Hancock v. Borough of Oaklyn, 347 N.J. Super. 350, 361 (App. Div. 2002).

Plaintiff argues that he has alleged “lasting prejudice” as a result of his harassment

Specifically, Plaintiff states:

Mayor Zimmer{‘s] unconstitutional political patronage scheme,

Executive Director Gareia was and continues to be subjected by

the Defendants and others to a pattem of retaliatory and harassing,

conduct, including but not limited to: frequent threats, extortion,

intimidation, defamatory statements about his professional abilities

through internet websites and bloggers friendly to Mayor Zimmer,

unfair criticism of his work performance, continuous threats to his

employment, and other tangible and intangible adverse

employment activities

Pla’s Br. at 14 (citing Complaint at $59)

Plaintiff correctly asserts that Kadetsky and Whistleblower 1, supra, take no position on

the issue of whether harassment alone triggered lasting prejudice and that any conclusions

reached therein on the topic are dicta.

However, Plaintiff provides no case law to indicate that the harassment alleged, and the

facts pled in the complaint amount to “lasting prejudice.”

Plaintif?'s does not plead facts which, even when liberally construed, are sufficient to

state a CEPA claim. Plaintiff has not pled conduct by Mayor Zimmer for which he is entitled to

“blow the whistle.” Additionally, Plaintiff has not pled facts sufficient to support a conclusion

‘that Mayor Zimmer is Plaintiff's employer. Based on these conclusions, Plaintiff's CEPA claim

against Mayor Zimmer, as currently pled, is insufficient as a matter of taw.

ike the federal courts in Kadetsky and Whistleblower 1, this Court need not take a

stance on whether these allegations amount to a lasting prejudice.

B. NICRA

‘The NICRA, NLS.

substantive due process rights, equal protection rights, and privileges and immunities secured by

6-1 et sea,, provides a private right of action for the depri

the laws of the United States or New Jersey where the same are “interfered with or attempted to

be interfered with, by threats, intimidation or coercion by a person acting under color of law.

PNISA, 10:6-26).

Plaintiff asserts that his right to free speech and political affiliation was infringed upon by

Mayor Zimmer, Plaintiff argues that the right to speak under the New Jersey Constitution is

broader than that afforded by the Federal Constitution, Specifically, Plaintiff cites Article 1,

sections 6 and 18, which give individuals the right to “make known their opinions to their

representatives”, “petition for redress of grievances”, and to “freely speak, write and publish his,

sentiments on all subjects.”

However, on this motion, the extent of the right is not at issue. The only question the Court

must address on this motion is whether Plaintiff has alleged a violation of his free speech rights

and whether that claim is actionable.

In order for Plaintiff's free specch claim to be actionable, the conduct must be “sufficient to

deter a person of ordinary firmaness from exercising his First Amendment rights.” Mokee v, Hart,

436 F.3d 165, 170 (3d. Cir. 2006) (interpreting 42 U.S.C. § 1983, the federal counterpart to the

N.JCRA). The effect of the conduct must be more than de mininmus, Id.

The facts pled, even when generously and liberally construed, do not indicate that Plaintift

was deterred from speaking out or affiliating himself politically against Mayor Zimmer, He

continues to criticize the Zimmer administration and assert his own policies rather than Mayor

Zimmer's, Plaintiff is still the Executive Director of the Housing Authority and does not allege a

decrease in compensation, or loss of benefits, Plaintiff does not allege that his duties have

changed or that his ability has been impaired by the actions of Mayor Zimmer. In fact, Plaintiff

states that he defeated all of Mayor Zimmer's attempts toi

iplement her policies or take formal

action against him,

Plaintiff asserts that political discharge cases are governed by Elrod v. Bums, 427 U.S, 347

(1976) and Branti_v, Finkel, 445 U.S. 507 (1980). In Elvod, the Court held that threatened

discharge was actionable. Both Plaintiff and Defendants agree that policy-making officials are

exempted from Elrod. 427 U.S. at 355-57, The Court also notes that there is no indication in the

Complaint that Plaintiff and Mayor Zimmer are members of different political parties.

‘The Court takes no position on whether Plaintiff is a policy making official, as that

conclusion need not be drawn to resolve this motion, From the arguments presented by PlaintifY,

the applicability of Elrod to this.case is unclear, There was a Rice notice, which indicated that

Plaintif?’s employment may be discussed, but he was not threatened with discharge and, based

on the motion record, the discussion apparently never came to fruition. Plaintiff does not

provide the Court with any precedent that shows the service of a Rice notice is “sufficient to

deter a person of ordinary firmness from exercising his First Amendment rights.” Mckee v, Hart,

436 F.3d 165, 170 Gd. Cir. 2006). Therefore, to the extent Elrod permits claims for threatened

discharge of a public employee, no such threat exists in the pleadings.

Plaintiff asserts that the Rige notice, and the harassment that followed “every time Plaintiff

defeated Mayor Zimmer” suffices to state a claim under the NICRA. Plaintiff alleges that his

“emotional distress and anxiety increased to a dangerous level, which affected his deily

activities, work performance and relationship with his family. The Defendants had effectively

created a hostile work environment which became intolerable.” Pla’s Br. at 20 (Citing Complaint

at $55). However, despite the “intolerability” of the environment, Plaintiff voluntarily retained

his position. While in that position, he continues to speak out against the Mayor, oppose the

Mayor's agenda and affiliate himself politically against the Mayor.

Plaintiff's complaint does not state a cause of action under the NICRA. Plaintiff’ does not

plead facts that show his employment was actually threatened or that such any action alleged

chilled his speech. Therefore, Plaintiff's NICRA claim against Mayor

immer is also insufficient

asa matter of law.

For the sake of completeness, the Court also addresses Mayor Zimmer’s final argument in

favor of dismissal.

Mayor Zimmer alleges that the suit against her in her official capacity is duplicative of the

claim against the Housing Authority. Plaintiff cites Kentucky v. Graham, 473 U.S. 159 (1985),

for the proposition that an “official capacity suit" under 42

§ 1983 is really a claim

‘against the entity and that where claims are pled against both entities and their public officials,

the claim against the official must be dismissed, That reasoning does not, based on the facts

currently before the Court, apply to this ease.

Her

e, Mayor Zimmer is not an officer or agent of the Hous

ig Authority. If she were,

Plaintiff's CEPA claim might be viable

supra, Section IIIA. In order for the reasoning of

Graham to apply, Mayor Zimmer, the City of Hoboken and the Hoboken Housing Authority

would all need to be part of the same “entity”, presumably Hoboken. However, Defendants do

not provide the Court with facts sufficient fo reach a conclusion that such is true. Plaintiff has not

pled facts which support that conclusion, Therefore, the Court cannot find, based on the facts

presented to the Court on this motion to dismiss, that the suit against Mayor Zimmer in her

official capacity is duplicative at this time.

Additionally the Court notes that there is no indication that the suit against Mayor 2

immer in

her individual capacity is in any way dupli

ive. However, because the Court finds, for the

reasons previously stated, that there is no basis for the CEPA or NICRA claim against Mayor

Zimmer, the CEA and NJCRA claims ageinst Mayor Zimmer in her personal capacity are also

insufficient as a matier of law.

IV. Co-Defendant, Mr. Stuvier and the Housing Authority's Motion

Plaintiff also alleges violations of CEPA and the NICRA against Mr. Stuvier and the

Housing authority, Those claims are addressed in tun,

A. CEPA

Co-Defendants allege that Plaintiff's claims under CEPA are not actionable because there

‘was no tangible employment action. The requirements of a CEPA action are addressed in Section

BLA.

Plaintiff correctly argues that a CEPA claim requires only that the employee had a

“reasonable belief that the complained of activity is a violation . ...” Pla’s Br, at 11. However, it

does not appear from the motion record that Plaintiff pled that he had a reasonable belief the

HHA or Mr. Stuvier were acting to violate law or public policy, Again, the conduct about which

a plaintiff “blows the whistle” must “pose a threat of public harm, not merely private harm or

hharm only to the aggrieved employee.” Mebima

supra, 153 N.J. at 188. Plaintiff docs not

provide this Court with any conduct by Mr. Stuvier or the Housing Authority that is unlawftl or

contrary to public policy. The facts as pled, and granting all reasonable inferences in favor of

Plaintiff, indicate that the Board was exercising its authority, as an employer, in an attempt to

direct its employee.

Additionally, Plaintiff's allegations, as noted in Section IILA., supra, do not rise to a tangible

employment action cognizable under CEPA. ‘The terms and conditions of Plaintiff's employment

Beasley v. Passaic County, 377 N.J. Super. 585, 608 (App. Div.

2005). The conditions of Plaintiff's work have not been materially altered. See El-Sioufi v. St

have not been altered.

's Univ. Hosp., 382 N.J. Super. 145, 176 (App. Div, 2005). Plaintifi’s mere dissatisfaction

b Co., 362. NJ. Super,

with his employment is not actionable. See Cokus 3 ol Myers-S

366, 378 (Ch, Div. 2002) aff'd, 362 N.J. Super. 245 (App. Div. 2003),

Mr. Stuvier, allegedly on behalf of Mayor Zimmer, sought to have Plaintiff, the Executive

Director of the Housing Authority, act so as to support her policies. Plaintiff declined. That

conduct is not, without more, a violation of law that is actionable under CEPA,

Therefore, the Court finds that Plaintiff does not plead facts sufficient to sustain a CEPA.

claim, Accordingly, Plaintiff's CEPA claim against Mr. Stuvier and the Housing Authority is

insufficient as a matter of law.

To the extent that Defendants argue that CEPA requires Plaintiff to elect either a CEPA

claim or @ NICRA claim, the Court makes no findings as the issue is rendered moot by the

determination that Plaintiff's CEPA claim is insufficient as a matter of law. Notably, Plaintift

concedes that he may only prevail as to one of the claims. Pla’s Br. at 12.

B. NICRA

Co-Defendants also allege that Plaintiff's NICRA claim must be dismissed because there has

‘een no infringement of Plaintiff's free speech rights.

‘The standards for a NICRA claim were previously addressed in Section II]. B., supra. As to

the Housing Authority and Mr. Stuvier, the question of whether there was a constitutional