Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

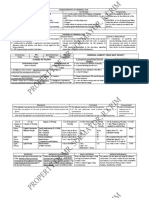

Vino v. People (1989) : Correccional As Minimum To Prision Mayor

Transféré par

MarisseAnne CoquillaTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Vino v. People (1989) : Correccional As Minimum To Prision Mayor

Transféré par

MarisseAnne CoquillaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Vino v.

People (1989)

At around 11pm of March 1985, while

ERNESTO was resting, he heard two

gunshots. Thereafter, he heard ROBERTO

(his son) cry out in a loud voice saying that he

had been shot. He immediately switched on

the lights of their house and when he looked

outside, he saw his son ROBERTO wounded.

Together with his wife and some neighbors,

they went down to meet ROBERTO who was

crying and calling for help. After coming

down, ERNESTO et al saw Lito VINO and

Jessie SALAZAR riding a bicycle coming from

the south towards their direction. VINO was

driving while SALAZAR was carrying an

armalite. Upon reaching ERNESTO's house,

they stopped to watch ROBERTO. SALAZAR

pointed his armalite at ERNESTO et al.

Thereafter, the two left. ROBERTO was

brought to the hospital. He was still conscious

and alive such that and PC/Col. Cacananta

was able to take his ante-mortem statement.

In the said statement which ROBERTO

signed with his own blood (how cool is

that?!), SALAZAR was identified as his

assailant. Then ROBERTO died.

On account of said ante-mortem statement

and the testimonies of the other witnesses,

VINO and SALAZAR were charged with

murder before the MTC of Balungao,

Pangasinan. MTC judge however referred the

case against SALAZAR to the Judge Advocate

Generals Office (JAGO) as he was a member

of the military hence, only the case

against VINO was given course. MTC referred

case for PI to fiscal and an information for

murder against VINO was ultimately filed

before the RTC of Pangasinan. Upon

arraignment, VINO entered a plea of not

guilty. Trial then commenced with the

presentation of evidence for the prosecution.

Instead of presenting evidence in his own

behalf, VINO filed a motion to dismiss for

insufficiency of evidence. RTC then rendered

decision finding VINO guilty as an accessory

to the crime of murder and imposing on him

the indeterminate penalty of prision

correccional as minimum to prision mayor

as maximum. He was also ordered to

indemnify the heirs of the victim

VINO appealed said conviction with the

CA but the same was denied, TCs decision

was affirmed in toto hence this appeal

During the pendency of the appeal, JAGO

has remanded SALAZARs case to the civil

courts as he was already discharged from

military service. Indeed, he was tried and

prosecuted in the RTC for the crime

committed and he was acquitted

Forthwith, VINO informed the Court of

such development

ISSUES:

1. WON his conviction as accessory can be

sustained even when the information charged

him as a principal [YES]

2. WON a finding of guilt as an accessory to

murder can stand in the light of the acquittal

of the alleged principal in a separate

proceeding [YES]

HELD: Petition is DISMISSED. Motion for

Reconsideration is also DENIED with

FINALITY.

RATIO:

1. This is not a case of a variance

between the offense charged and the

offense proved or established by the

evidence In this case, the correct offense

of murder was charged in the information.

The commission of the said crime was

established by the evidence; ergo, there is no

variance as to the offense committed. The

variance is in the participation or complicity

of the petitioner. While the petitioner was

being held responsible as a principal in the

information, the evidence adduced, however,

showed that his participation is merely that of

an accessory.

DOCTRINE: The greater responsibility

necessarily includes the lesser. An accused

can be validly convicted as an accomplice or

accessory under an information charging him

as a principal

The offense as charged in this case is

included in or necessarily includes the offense

proved in court, in which case the defendant

shall be convicted of the offense proved

included in that which is charged, or of the

offense charged included in that which is

proved

Under Art 16 of the Revised Penal Code,

the two other categories of persons

responsible for the commission of the same

offense, aside from the principal, are the

accomplice and the accessory. After the TCs

findings of fact, there is no doubt that the

crime of murder had been committed and

that the evidence tended to show that

SALAZAR was the assailant and VINO was

his companion

VINO must have been present during its

commission or at the very least must have

known its commission this is the only

logical

conclusion

considering

that

immediately after the shooting, VINO was

seen driving a bicycle with SALAZAR holding

an armalite, and they were together when

they left. It is thus clear that VINO actively

assisted SALAZAR in his escape. Petitioner's

liability is that of an accessory

At the onset, the prosecution should have

charged VINO as an accessory right then and

there because the degree of responsibility of

petitioner was apparent from the evidence

from the very get-go. At any rate, this lapse

did not violate the substantial rights of

petitioner

2. The trial of an accessory can

proceed without awaiting the result of

the separate charge against the

principal

The

corresponding

responsibilities of the principal, accomplice

and accessory are distinct from each other. As

long as the commission of the offense can be

duly

established

in

evidence

the

determination of the liability of the

accomplice or accessory can proceed

independently of that of the principal

It goes without saying therefore that

notwithstanding the acquittal of the principal

(say, due to the exempting circumstance of

minority or insanity), the accessory may

nevertheless be convicted if the crime was in

fact established

The acquittal of the principal will only

work as an acquittal for the accessory if such

acquittal was based on the finding that no

crime was committed inasmuch as the same

has happened by accident

IN THE CASE AT BAR, the commission of

the crime of murder and the responsibility of

the VINO as an accessory was established. As

to SALAZARs acquittal, it must be noted that

he was acquitted on the ground of reasonable

doubt. In SALAZARs trial, prosecution was

not able to present convincing evidence such

that the identity of the assailant was not

clearly established

In SALAZARs case, the ante-mortem

statement was competently controverted by

the defense. There was also some fatal

omissions on the part of the law enforcers

that constrained the TC judge to acquit

SALAZAR on reasonable doubt

The identity of the assailant is of no

material significance for the purpose of the

prosecution of the accessory. Even if the

assailant can not be identified the

responsibility of Vino as an accessory is

indubitable

Dissenting Opinions of Cruz and

Grio-Aquino, JJ:

The basic principle established by the

ponencia is agreeable that an accessory

may be convicted even when the identity of

the principal cannot be known as long as the

crime is established and the degree of

responsibility of the accused is proved.

HOWEVER, such general principle does

not find application in the case at bar because

the case of VINO is sui generis

VINO was convicted of having aided

SALAZAR who was named as the principal at

VINO's trial. At his own trial, SALAZAR was

acquitted for lack of sufficient identification.

VINO was convicted of helping in the escape

not of an unnamed principal but, specifically,

of SALAZAR. As SALAZAR himself has been

exonerated, the effect is that VINO is now

being held liable for helping an innocent

man, which is not a crime. VINO's conviction

should therefore be reversed

The accessory may not be convicted under

paragraph 3 of Article 19 of the Revised Penal

Code if the alleged principal is acquitted for,

in this instance, the principle that "the

accessory follows the principal" appropriately

applies

People vs Ortega

Laws

Applicable:

Art.

RPC

FACTS:

October 15, 1992 5:30 pm: Andre Mar

Masangkay (courting Raquel Ortega), Ariel

Caranto, Romeo Ortega, Roberto San Andres,

Searfin, Boyet and Diosdado Quitlong were

having a drinking spree with gin and finger

foods.

October 15, 1992 11:00 pm: Benjamin

Ortega, Jr. and Manuel Garcia who were

already drank joined them.

October 16, 1992 midnight: Andre

answering a call of nature went to the back

portion of the house and Benjamin followed

him. Suddenly, they heard a shout from

Andre Dont, help me! (Huwag, tulungan

ninyo ako!)

Diosdado and Ariel ran and saw Benjamin

on top of Andre who was lying down being

stabbed. Ariel got Benjamin Ortega, Sr.,

Benjamins father while Diosdado called

Romeo to pacify his brother. Romeo,

Benjamin and Manuel lifted Andre from the

canal and dropped him in the well. They

dropped stones to Andres body to weigh the

body down. Romeo warned Diosdado not to

tell anybody what he saw. He agreed so he

was allowed to go home. But, his conscience

bothered him so he told his mother, reported

it to the police and accompanied them to the

crime scene.

NBI Medico Legal Officer Dr. Ludivico J.

Lagat:

cause of death is drowning with

multiple stab wounds, contributory

13 stab wounds

stab wound on the upper left shoulder,

near the upper left armpit and left

chest wall- front

stab wound on the back left side of the

body and the stab wound on the back

right portion of the body back

Manuel Garcia alibi

He was asked to go home by his wife to

fetched his mother-in-law who

performed a ritual called tawas on

his sick daughter and stayed home

after

Benjamin

Ortega,

Jr.

story

o After Masangkay left, he left to urinate

and he saw Andre peeking through the room

of his sister Raquel. Then, Andre approached

him to ask where his sister was. When he

answered he didnt know, Andre punched

him so he bled and fell to the ground. Andre

drew a knife and stabbed him, hitting him on

the left arm, thereby immobilizing him.

Andre then gripped his neck with his left arm

and threatened to kill him. Unable to move,

Ortega shouted for help. Quitlong came,

seized the knife and stabbed Andre 10 times

with it. Andre then ran towards the direction

of the well. Then, he tended his wound in the

lips and armpit and slept.

Garcia is a brother-in-law of Benjamin

o Exempt by Article 20 of RPC

RTC: Benjamin and Manuel through

conspiracy and the taking advantage of

superior

strength

committed

murder

ISSUE: W/N Benjamin and Manuel should be

liable

for

murder.

HELD: NO. PARTLY GRANTED. Benjamin is

guilty only of homicide. Manuel deserves

acquittal

If Ortegas version of the assault was true,

he should have immediately reported the

matter to the police authorities. If Ortegas

version of the assault was true, he should

have immediately reported the matter to the

police authorities. It is incredible that

Diosdado would stab Andre 10 times

successively, completely ignoring Benjamin

who was grappling with Masangkay and that

Andre was choking him while being stabbed.

Abuse of superior strength requires

deliberate intent on the part of the accused to

take advantage of such superiority none

shown

o Andre was a 6-footer, whereas Ortega, Jr.

was

only

54

Article 4, par. 1, of the Revised Penal Code

states that criminal liability shall be incurred

by any person committing a felony (delito)

although the wrongful act done be different

from

that

which

he

intended.

o

The

essential

requisites

1. the intended act is felonious assisting

Benjamin by carrying the body to the well

2. the resulting act is likewise a felony concealing the body of the crime to prevent

its

discovery

3. the unintended albeit graver wrong was

primarily caused by the actors wrongful acts

(praeter intentionem) still alive and was

drowned

to

death

a person may be convicted of homicide

although he had no original intent to kill

ART. 20. Accessories who are

exempt from criminal liability. -- The

penalties prescribed for accessories

shall not be imposed upon those who

are such with respect to their spouses,

ascendants, descendants, legitimate,

natural, and adopted brothers and

sisters, or relatives by affinity within

the same degrees with the single

exception of accessories falling within

the provisions of paragraph 1 of the

next preceding article.

The penalty for homicide is reclusion

temporal under Article 249 of the Revised

Penal Code, which is imposable in its medium

period, absent any aggravating or mitigating

circumstance, as in the case of Appellant

Ortega. Because he is entitled to the benefits

of the Indeterminate Sentence Law, the

minimum term shall be one degree lower,

that is, prision mayor.

Dizon-Pamintuan vs People

On or about and during the period from

February 12, to February 24, 1988, inclusive,

in the City of Manila, Philippines, the said

accused, with intent of gain for herself or for

another, did then and there wilfully,

unlawfully and knowingly buy and keep in

her possession and/or sell or dispose of the

following jewelries, to wit: one (1) set of

earrings, a ring studded with diamonds in a

triangular style, one (1) set of earrings

(diamond studded) and one (1) diamondstudded crucifix, or all valued at

P105,000.00, which she knew or should have

known to have been derived from the

proceeds of the crime of robbery committed

by Joselito Sacdalan Salinas against the

owner

Teodoro

and

Luzviminda

3

Encarnacion.

On the basis of the testimonies of prosecution

witnesses Teodoro Encarnacion (one of the

offended parties), Cpl. Ignacio Jao, Jr., and

Pfc. Emmanuel Sanchez, both of the Western

Police District, the trial court promulgated on

16 November 1990 its decision, the

dispositive portion of which reads:

WHEREFORE, the prosecution having

proved the guilty of the accused for violation

of Presidential Decree No. 1612 beyond

reasonable doubt, the accused Norma DizonPamintuan is hereby sentenced to suffer an

indeterminate penalty of imprisonment from

FOURTEEN (14) YEARS ofprision mayor to

NINETEEN

(19)

YEARS

of reclusion

temporal.

No civil liability in view of the recovery of the

items, subject-matter of this case.

With costs. 4

Teodoro

Encarnacion,

Undersecretary,

Department of Public Works and Highways

testified that he has just arrived at his

residence

located

at

Better

Living

Subdivision, Paraaque at around 9:45 p.m.

of February 12, 1988 coming from the Airport

and immediately proceeded inside the house,

leaving behind his driver and two

housemaids outside to pick-up his personal

belongings from his case. It was at this point

that five unidentified masked armed persons

appeared from the grassy portion of the lot

beside the house and poked their guns to his

driver and two helpers and dragged them

inside his house. That the men pointed a gun

at him and was made to lie face down on the

floor. The other occupants, namely his wife,

the maids and his driver were likewise made

to lie on the floor. Thereafter, the robbers

ransacked the house and took away jewelries

and other personal properties including cash.

After the intruders left the house he reported

the matter immediately to the police. He was

then interviewed by the Paraaque police and

was informed that an operation group would

be assigned to the case.

He likewise reported the matter to the

Western Police District on February 15, 1988.

Two days later, a group of WPD operatives

came over to his house and he was asked to

prepare a list of items of jewelry and other

valuables that were lost including a sketch of

distinctive items. He was later told that some

of the lost items were in Chinatown area as

tipped by the informer the police had

dispatched. That an entrapment would be

made with their participation, on February

14, 1988. As such, they went to Camp Crame

at around 9:00 a.m. and arrived at the

vicinity of 733 Florentino Torres Street, Sta.

Cruz, Manila at about 10:00 a.m.; that he is

with his wife posed as a buyer and were able

to recognize items of the jewelry stolen

displayed at the stall being tended by Norma

Dizon Pamintuan; the pieces were: 1 earring

and ring studded with diamonds worth

P75,000 bought from estimator Nancy Bacud

(Exh. "C-2"), 1 set of earring diamond worth

P15,000 (Exh. "C-3") and 1 gold chain with

crucifix worth P3,000 (Exh. "C-4").

surrendered the items and gave them to [his]

wife." 6

Corporal Ignacio Jao, Jr. of the WPD testified

that he was with the spouses Teodoro

Encarnacion, Jr. in the morning of February

24, 1988 and they proceeded to Florentino

Torres Street, Sta. Cruz, Manila at the stall of

Norma Dizon-Pamintuan together with Sgt.

Perez. After the spouses Encarnacion

recognized the items subject matter of the

robbery at the display window of the stall

being tended by the herein accused, they

invited the latter to the precinct and

investigated the same. They likewise brought

the said showcase to the WPD station. He

further testified that he has no prior

knowledge of the stolen jewelries of the

private complainant from one store to

another.

On the other hand, the version of the defense,

as testified to by Rosito Dizon-Pamintuan, is

summarized by the trial court thus:

Pfc. Emmanuel Sanchez of the WPD testified

that he reported for duty on February 24,

1988; that he was with the group who

accompanied the spouses Encarnacion in Sta.

Cruz, Manila and was around when the

couple saw some of the lost jewelries in the

display stall of the accused. He was likewise

present during the early part of the

investigation of the WPD station. 5

The recovery of the pieces of jewelry, on the

basis of which the trial court ruled that no

civil liability should be adjudged against the

petitioner, took place when, as testified to by

Teodoro

Encarnacion,

the

petitioner

"admitted that she got the items but she did

not know they were stolen [and that] she

The defense presented only the testimony of

Rosito Dizon-Pamintuan who testified that he

is the brother of Norma Dizon-Pamintuan

and that sometime around 11:00 a.m. of

February 24, 1985, he, together with the

accused went infront of the Carinderia along

Florentino Torres Street, Sta. Cruz, Manila

waiting for a vacancy therein to eat lunch.

Suddenly, three persons arrived and he

overheard that Cpl. Jao told her sister to get

the jewelry from inside the display window

but her sister requested to wait for Fredo, the

owner of the stall. But ten minutes later when

said Fredo did not show up, the police officer

opened the display window and got the

contents of the same. The display stall was

hauled to a passenger jeepney and the same,

together with the accused were taken to the

police headquarters. He likewise testified that

he accompanied his sister to the station and

after investigation was sent home. 7

In convicting the petitioner, the trial court

made the following findings:

The prosecution was able to prove by

evidence that the recovered items were part

of the loot and such recovered items belong to

the spouses Encarnacion, the herein private

complainants. That such items were

recovered by the Police Officers from the stall

being tended by the accused at that time. Of

importance, is that the law provides a

disputable presumption of fencing under

Section 5 thereof, to wit:

of the Anti-Fencing Law of 1979 (P.D. No.

1612), to wit:

Mere possession of any goods, article, item

object, or anything of value which has been

the subject of robbery or thievery shall

be prima facie evidence of fencing.

1. A crime of robbery or theft has been

committed;

There is no doubt that the recovered items

were found in the possession of the accused

and she was not able to rebut the

presumption though the evidence for the

defense alleged that the stall is owned by one

Fredo. A distinction should likewise be made

between ownership and possession in

relation to the act of fencing. Moreover, as to

the value of the jewelries recovered, the

prosecution was able to show that the same is

Ninety

Three

Thousand

Pesos

8

(P93,000.00).

2. A person, not a participant in said crime,

buys, receives, possesses, keeps, acquires,

conceals, sells or disposes, or buys and sells;

or in any manner deals in any article or item,

object or anything of value;

3. With personal knowledge, or should be

known to said person that said item, object or

anything of value has been derived from the

proceeds of the crime of robbery or theft;

4. With intent to gain for himself or for

another;

have been established by positive and

convincing evidence of the prosecution . . .

...

The petitioner then appealed her conviction

to the Court of Appeals (CA-G.R. CR No.

11024) where she raised two issues: (1) that

the judgment was based on a mere

presumption, and (2) that the prosecution

failed to show that the value of the jewelry

recovered is P93,000.00.

In its challenged decision of 29 March 1993,

the Court of Appeals disposed of the first

issue in this wise:

The

guilt

of

accused-appellant

was

established beyond reasonable doubt. All the

elements of the crime of fencing in violation

The fact that a crime of robbery has been

committed on February 12, 1988 is

established by the testimony of private

complainant Teodoro T. Encarnacion who

immediately reported the same to Paraaque

Police Station of the Southern Police District

(TSN, Hearings of October 3, 1988,

November 9, 1988 and January 11, 1989; Exh.

A) and submitted a list and sketches of the

jewelries robbed, among other things, from

their residence located at Better Living

Subdivision, Paraaque, Metro Manila (Exh.

C,

C-1 to C-4 and D).

The second element is likewise established by

convincing evidence. On February 24, 1988,

accused-appellant was found selling the

jewelries (Exhs. C-2, C-3 and C-4) which was

displayed in a showcase in a stall located at

Florentino Street, Sta. Cruz, Manila.

[Testimonies of Teodoro Encarnacion (id.

supra); Cpl. Ignacio Jao (TSN, Hearing of

February 13, 1989) and Pfc. Emmanuel

Sanchez (TSN, Hearing of June 4, 1989)].

On the element of knowledge that the items

are derived from the proceeds of the crime of

robbery and of intent to gain for herself or for

another, the Anti-Fencing Law provides:

Sec. 5. Presumption of Fencing. Mere

possession of any good, article, item, object,

or anything of value which has been the

subject of robbery or thievery shall be prima

facie evidence of fencing.

Knowledge and intent to gain are proven by

the fact that these jewelries were found in

possession of appellant and they were

displayed for sale in a showcase being tended

by her in a stall along Florentino Street, Sta.

Cruz, Manila. 9

Nevertheless, the Court of Appeals was of the

opinion that there was not enough evidence

to prove the value of the pieces of jewelry

recovered, which is essential to the

imposition of the proper penalty under

Section

3

of

P.D.

No. 1612. It opined that the trial court erred

in concluding that "the value of the recovered

jewelries is P93,000.00 based on the bare

testimony of the private complainant and the

self-serving list he submitted (Exhs. C, C-2

and C-4, TSN, Hearing of October 3,

1993)." 10

The dispositive portion of the Court of

Appeals' decision reads:

WHEREFORE, finding that the trial court did

not commit any reversible error, its decision

dated October 26, 1990 convincing accused

appellant is hereby AFFIRMED with the

modification that the penalty imposed is SET

ASIDE and the Regional Trial Court (Branch

20) of Manila is ordered toreceive evidence

with respect to the correct valuation of the

properties involved in this case, marked as

Exhibits "C", "C-2" and "C-4" for the sole

purpose of determining the proper penalty to

be meted out against accused under Section

3, P.D. No. 1612. Let the original records be

remanded immediately. 11

Hence, this petition wherein the petitioner

contends that:

I

PUBLIC

RESPONDENT

COURT

OF

APPEALS

MANIFESTLY

ERRED

IN

AFFIRMING THE DECISION OF PUBLIC

RESPONDENT

JUDGE

CAEBA,

IN

BLATANT DISREGARD OF APPLICABLE

LAW

AND

WELL-ESTABLISHED

JURISPRUDENCE.

II

PUBLIC

RESPONDENT

COURT

OF

APPEALS

MANIFESTLY

ERRED

IN

REMANDING THE CASE TO THE COURT A

QUO FOR RECEPTION OF EVIDENCE FOR

THE PURPOSE OF DETERMINING THE

CORRECT PENALTY TO BE IMPOSED. 12

On 23 February 1994, after the public

respondents had filed their Comment and the

petitioner her Reply to the Comment, this

Court gave due course to the petition and

required the parties to submit their respective

memoranda, which they subsequently

complied with.

The first assigned error is without merit.

Fencing, as defined in Section 2 of P.D. No.

1612 (Anti-Fencing Law), is "the act of any

person who, with intent to gain for himself or

for another, shall buy, receive, possess, keep,

acquire, conceal, sell or dispose of, or shall

buy and sell, or in any manner deal in any

article, item, object or anything of value

which he knows, or should be known to him,

to have been derived from the proceeds of the

crime of robbery or theft."

Before P.D. No. 1612, a fence could only be

prosecuted for and held liable as

an accessory, as the term is defined in Article

19 of the Revised Penal Code. The penalty

applicable to an accessory is obviously light

under the rules prescribed in Articles 53, 55,

and 57 of the Revised Penal Code, subject to

the qualification set forth in Article 60

thereof. Nothing, however, the reports from

law enforcement agencies that "there is

rampant robbery and thievery of government

and private properties" and that "such

robbery and thievery have become profitable

on the part of the lawless elements because of

the existence of ready buyers, commonly

known as fence, of stolen properties," P.D.

No. 1612 was enacted to "impose heavy

penalties on persons who profit by the effects

of the crimes of robbery and theft." Evidently,

the accessory in the crimes of robbery and

theft could be prosecuted as such under the

Revised Penal Code or under P.D. No. 1612.

However, in the latter case, he ceases to be a

mere accessory but becomes a principal in

the crime of fencing. Elsewise stated, the

crimes of robbery and theft, on the one hand,

and fencing, on the other, are separate and

distinct offenses. 13 The state may thus choose

to prosecute him either under the Revised

Penal Code or P.D. No. 1612, although the

preference for the latter would seem

inevitable considering that fencing is

a malum prohibitum, and P.D. No. 1612

creates a presumption of fencing 14 and

prescribes a higher penalty based on the

value of the property. 15

The elements of the crime of fencing are:

1. A crime of robbery or theft has been

committed;

2. The accused, who is not a principal or

accomplice in the commission of the crime of

robbery or theft, buys, receives, possesses,

keeps, acquires, conceals, sells or disposes, or

buys and sells, or in any manner deals in any

article, item, object or anything of value,

which has been derived from the proceeds of

the said crime;

3. The accused knows or should have known

that the said article, item, object or anything

of value has been derived from the proceeds

of the crime of robbery or theft; and

4. There is, on the part of the accused, intent

to gain for himself or for another.

In the instant case, there is no doubt that the

first, second, and fourth elements were duly

established. A robbery was committed on 12

February 1988 in the house of the private

complainants who afterwards reported the

incident to the Paraaque Police, the Western

Police District, the NBI, and the CIS, and

submitted a list of the lost items and sketches

of the jewelry taken from them (Exhibits "C"

and "D"). Three of these items stolen, viz., (a)

a pair of earrings and ring studded with

diamonds worth P75,000.00 (Exhibit "C-2");

(b) one set of earrings worth P15,000.00

(Exhibit "C-3"); and (c) a chain with crucifix

worth P3,000.00 (Exhibit "C-4"), were

displayed for sale at a stall tended to by the

petitioner in Florentino Torres Street, Sta.

Cruz, Manila. The public display of the

articles for sale clearly manifested an intent

to gain on the part of the petitioner.

The more crucial issue to be resolved is

whether the prosecution proved the existence

of the third element: that the accused knew or

should have known that the items recovered

from her were the proceeds of the crime of

robbery or theft.

One is deemed to know a particular fact if he

has the cognizance, consciousness or

awareness thereof, or is aware of the

existence of something, or has the

acquaintance with facts, or if he has

something within the mind's grasp with

certitude and clarity. 16 When knowledge of

the existence of a particular fact is an element

of an offense, such knowledge is established if

a person is aware of a high probability of its

existence unless he actually believes that it

does not exist. 17 On the other hand, the words

"should know" denote the fact that a person

of reasonable prudence and intelligence

would ascertain the fact in performance of his

duty to another or would govern his conduct

upon

assumption

that

such

fact

18

exists. Knowledge refers to a mental state of

awareness about a fact. Since the court

cannot penetrate the mind of an accused and

state with certainty what is contained therein,

it must determine such knowledge with care

from the overt acts of that person. And given

two equally plausible states of cognition or

mental awareness, the court should choose

the one which sustains the constitutional

presumption of innocence. 19

Since Section 5 of P.D. No. 1612 expressly

provides that "[m]ere possession of any good,

article, item, object, or anything of value

which has been the subject of robbery or

thievery shall be prima facie evidence of

fencing," it follows that the petitioner is

presumed to have knowledge of the fact that

the items found in her possession were the

proceeds of robbery or theft. The

presumption is reasonable for no other

natural or logical inference can arise from the

established fact of her possession of the

proceeds of the crime of robbery or theft. This

presumption

does

not

offend

the

presumption of innocence enshrined in the

fundamental law. 20 In the early case

of United

States

vs.

Luling, 21 this Court held:

It has been frequently decided, in case of

statutory crimes, that no constitutional

provision is violated by a statute providing

that proof by the state of some material

fact or

facts

shall

constitute prima

facieevidence of guilt, and that then the

burden is shifted to the defendant for the

purpose of showing that such act or acts are

innocent and are committed without

unlawful intention. (Commonwealth vs.

Minor, 88 Ky., 422.)

In some of the States, as well as in England,

there exist what are known as common law

offenses. In the Philippine Islands no act is a

crime unless it is made so by statute. The

state having the right to declare what acts are

criminal, within certain well defined

limitations, has a right to specify what act or

acts shall constitute a crime, as well as what

proof shall constitute prima facie evidence of

guilt, and then to put upon the defendant the

burden of showing that such act or acts are

innocent and are not committed with any

criminal intent or intention.

In his book on constitutional law, 22 Mr.

Justice Isagani A. Cruz said:

Nevertheless, the constitutional presumption

of innocence may be overcome by contrary

presumptions based on the experience of

human conduct [People vs. Labara, April 20,

1954]. Unexplained flight, for example, may

lead to an inference of guilt, as 'the wicked

flee when no man pursueth, but the righteous

is as bold as a lion. Failure on the part of the

accused to explain his possession of stolen

property may give rise to the reasonable

presumption that it was he himself who had

stolen it [U.S. vs. Espia, 16 Phil. 506]. Under

our Revised Penal Code, the inability of an

accountable officer to produce funds or

property entrusted to him will be

considered prima facieevidence that he has

appropriated them to his personal use [Art.

217]. According to Cooley, the constitutional

presumption will not apply as long as there is

"some rational connection between the fact

proved and the ultimate fact presumed, and

the inference of one fact from proof of

another shall not be so unreasonable as to be

purely arbitrary mandate" [1 Cooley, 639].

The petitioner was unable to rebut the

presumption under P.D. No. 1612. She relied

solely on the testimony of her brother which

was

insufficient

to

overcome

the

presumption, and, on the contrary, even

disclosed that the petitioner was engaged in

the purchase and sale of jewelry and that she

used to buy from a certain Fredo. 23

Fredo was not presented as a witness and it

was not established that he was a licensed

dealer or supplier of jewelry. Section 6 of P.D.

No. 1612 provides that "all stores,

establishments or entitles dealing in the buy

and sell of any good, article, item, object or

anything of value obtained from an

unlicensed dealer or supplier thereof, shall

before offering the same for sale to the public,

secure the necessary clearance or permit from

the station commander of the Integrated

National Police in the town or city where such

store, establishment or entity is located."

Under

the

Rules

and

24

Regulations promulgated to carry out the

provisions of Section 6, an unlicensed

dealer/supplier refers to any person,

partnership, firm, corporation, association or

any other entity or establishment not licensed

by the government to engage in the business

of dealing in or supplying "used secondhand

articles," which refers to any good, article,

item, object or anything of value obtained

from an unlicensed dealer or supplier,

regardless of whether the same has actually

or in fact been used.

We do not, however, agree with the Court of

Appeals that there is insufficient evidence to

prove the actual value of the recovered

articles.

As found by the trial court, the recovered

articles had a total value of P93,000.00,

broken down as follows:

a) one earring and ring studded with

diamonds (Exh. "C-2") P75,000.00

b) one set of earring (Exh. "C-3")

P15,000.00

c) one gold chain with crucifix (Exh. "C-4")

P3,000.00

These findings are based on the testimony of

Mr. Encarnacion 25 and on Exhibit "C," 26 a

list of the items which were taken by the

robbers on 12 February 1988, together with

the corresponding valuation thereof. On

cross-examination, Mr. Encarnacion reaffirmed his testimony on direct examination

that the value of the pieces of jewelry

described

in

Exhibit

"C-2"

is

27

P75,000.00 and that the value of the items

described in Exhibit "C-3" is P15,000.00,

although he admitted that only one earring

and not the pair was recovered. 28 The

cross-examination withheld any question on

the gold chain with crucifix described in

Exhibit "C-4." In view, however, of the

admission that only one earring was

recovered of the jewelry described in Exhibit

"C-3," it would be reasonable to reduce the

value from P15,000.00 to P7,500.00.

Accordingly, the total value of the pieces of

jewelry displayed for sale by the petitioner

and established to be part of the proceeds of

the robbery on 12 February 1988 would be

P87,000.00.

Section 3(a) of P.D. No. 1612 provides that

the penalty of prision mayor shall be

imposed upon the accused if the value of the

property involved is more than P12,000.00

but does not exceed P22,000.00, and if the

value of such property exceeds the latter sum,

the penalty of prision mayor should be

imposed in its maximum period, adding one

year for each additional P10,000.00; the total

penalty which may be imposed, however,

shall not exceed twenty years. In such cases,

the penalty shall be termed reclusion

temporal and

the

accessory

penalty

pertaining thereto provided in the Revised

Penal Code shall also be imposed. The

maximum penalty that can be imposed in this

case would then be eighteen (18) years and

five (5) months, which is within the range

of reclusion temporalmaximum. Applying the

Indeterminate Sentence law which allows the

imposition of an indeterminate penalty

which, with respect to offenses penalized by a

special law, shall range from a minimum

which shall not be lower than the minimum

prescribed by the special law to a maximum

which should not exceed the maximum

provided therein, the petitioner can thus be

sentenced to an indeterminate penalty

ranging from ten (10) years and one (1) day

of prision mayor maximum, as minimum to

eighteen (18) years and five (5) months

of reclusion

temporalmaximum

as maximum, with the accessory penalties

corresponding to the latter.

In the light of the foregoing, the Court of

Appeals erred in setting aside the penalty

imposed by the trial court and in remanding

the case to the trial court for further reception

of evidence to determine the actual value of

the pieces of jewelry recovered from the

petitioner and for the imposition of the

appropriate penalty.

We do not agree with the petitioner's

contention, though, that a remand for further

reception of evidence would place her in

double jeopardy. There is double jeopardy

when the following requisites concur: (1) the

first jeopardy must have attached prior to the

second, (2) the first jeopardy must have

validly been terminated, and (3) the second

jeopardy must be for the same offense as that

in the first. 29 Such a concurrence would not

occur assuming that the case was remanded

to the trial court.

WHEREFORE, the instant petition is partly

GRANTED by setting aside the challenged

decision of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R.

CR No. 11024 insofar as it sets aside the

penalty imposed by Branch 20 of the

Regional Trial Court of Manila in Criminal

Case No. 88-64954 and orders the remand of

the case for the trial court to receive evidence

with respect to the correct value of the

properties involved. The decision of the

Regional Trial Court is AFFIRMED subject to

the modification of the penalty which is

hereby reduced to an indeterminate penalty

ranging from Ten (10) years and One (1) day

of Prision Mayor maximum as minimum to

Eighteen (18) years and Five (5) months

of Reclusion

Temporal maximum

as maximum, with the accessory penalties of

the latter.

Complainant Rosita Lim is the proprietor

of Bueno Metal Industries, located at 301

Jose Abad Santos St., Tondo, Manila,

engaged in the business of manufacturing

propellers or spare parts for boats. Manuelito

Mendez was one of the employees working

for her. Sometime in February 1991,

Manuelito Mendez left the employ of the

company. Complainant Lim noticed that

some of the welding rods, propellers and boat

spare parts, such as bronze and stainless

propellers and brass screws were missing.

She conducted an inventory and discovered

that propellers and stocks valued at

P48,000.00, more or less, were missing.

Complainant Rosita Lim informed Victor Sy,

uncle of Manuelito Mendez, of the loss.

Subsequently, Manuelito Mendez was

arrested in the Visayas and he admitted that

he and his companion Gaudencio Dayop stole

from the complainants warehouse some boat

spare parts such as bronze and stainless

propellers and brass screws. Manuelito

Mendez asked for complainants forgiveness.

He pointed to petitioner Ramon C. Tan as the

one who bought the stolen items and who

paid the amount of P13,000.00, in cash to

Mendez and Dayop, and they split the

amount with one another. Complainant did

not file a case against Manuelito Mendez and

Gaudencio Dayop.

SO ORDERED.

Cruz, Bellosillo, Quiason and Kapunan, JJ.,

concur.

Tan vs People

On relation of complainant Lim, an

Assistant City Prosecutor of Manila filed with

the Regional Trial Court, Manila, Branch 19,

an information against petitioner charging

him with violation of Presidential Decree No.

1612 (Anti-Fencing Law) committed as

follows:

That on or about the last week of February

1991, in the City of Manila, Philippines, the

said accused, did then and there wilfully,

unlawfully and feloniously knowingly receive,

keep, acquire and possess several spare parts

and items for fishing boats all valued at

P48,130.00 belonging to Rosita Lim, which

he knew or should have known to have been

derived from the proceeds of the crime of

theft.

Contrary to law.

Upon arraignment on November 23,

1992, petitioner Ramon C. Tan pleaded not

guilty to the crime charged and waived pretrial. To prove the accusation, the prosecution

presented the testimonies of complainant

Rosita Lim, Victor Sy and the confessed thief,

Manuelito Mendez.

On the other hand, the defense presented

Rosita Lim and Manuelito Mendez as hostile

witnesses and petitioner himself. The

testimonies

of

the

witnesses

were

summarized by the trial court in its decision,

as follows:

ROSITA LIM stated that she is the owner of

Bueno Metal Industries, engaged in the

business of manufacturing propellers,

bushings, welding rods, among others

(Exhibits A, A-1, and B). That sometime in

February 1991, after one of her employees left

the company, she discovered that some of the

manufactured spare parts were missing, so

that on February 19, 1991, an inventory was

conducted and it was found that some

welding rods and propellers, among others,

worth P48,000.00 were missing. Thereafter,

she went to Victor Sy, the person who

recommended

Mr.

Mendez

to

her.

Subsequently, Mr. Mendez was arrested in

the Visayas, and upon arrival in Manila,

admitted to his having stolen the missing

spare parts sold then to Ramon Tan. She then

talked to Mr. Tan, who denied having bought

the same.

When presented on rebuttal, she stated that

some of their stocks were bought under the

name of Asia Pacific, the guarantor of their

Industrial Welding Corporation, and stated

further that whether the stocks are bought

under the name of the said corporation or

under the name of William Tan, her husband,

all of these items were actually delivered to

the store at 3012-3014 Jose Abad Santos

Street and all paid by her husband.

That for about one (1) year, there existed a

business relationship between her husband

and Mr. Tan. Mr. Tan used to buy from them

stocks of propellers while they likewise

bought from the former brass woods, and

that there is no reason whatsoever why she

has to frame up Mr. Tan.

MANUELITO MENDEZ stated that he

worked as helper at Bueno Metal Industries

from November 1990 up to February 1991.

That sometime in the third week of February

1991, together with Gaudencio Dayop, his coemployee, they took from the warehouse of

Rosita Lim some boat spare parts, such as

bronze and stainless propellers, brass screws,

etc. They delivered said stolen items to

Ramon Tan, who paid for them in cash in the

amount of P13,000.00. After taking his share

(one-half (1/2) of the amount), he went home

directly to the province. When he received a

letter from his uncle, Victor Sy, he decided to

return to Manila. He was then accompanied

by his uncle to see Mrs. Lim, from whom he

begged for forgiveness on April 8, 1991. On

April 12, 1991, he executed an affidavit

prepared by a certain Perlas, a CIS personnel,

subscribed to before a Notary Public

(Exhibits C and C-1).

VICTORY [sic] SY stated that he knows both

Manuelito Mendez and Mrs. Rosita Lim, the

former being the nephew of his wife while the

latter is his auntie. That sometime in

February 1991, his auntie called up and

informed him about the spare parts stolen

from the warehouse by Manuelito Mendez. So

that he sent his son to Cebu and requested his

kumpadre, a police officer of Sta. Catalina,

Negros Occidental, to arrest and bring

Mendez back to Manila. When Mr. Mendez

was brought to Manila, together with Supt.

Perlas of the WPDC, they fetched Mr. Mendez

from the pier after which they proceeded to

the house of his auntie. Mr. Mendez admitted

to him having stolen the missing items and

sold to Mr. Ramon Tan in Sta. Cruz, Manila.

Again, he brought Mr. Mendez to Sta. Cruz

where he pointed to Mr. Tan as the buyer, but

when confronted, Mr. Tan denied the same.

ROSITA LIM, when called to testify as a

hostile witness, narrated that she owns Bueno

Metal Industries located at 301 Jose Abad

Santos Street, Tondo, Manila. That two (2)

days after Manuelito Mendez and Gaudencio

Dayop left, her husband, William Tan,

conducted an inventory and discovered that

some of the spare parts worth P48,000.00

were missing. Some of the missing items were

under the name of Asia Pacific and William

Tan.

MANUELITO MENDEZ, likewise, when

called to testify as a hostile witness, stated

that he received a subpoena in the Visayas

from the wife of Victor Sy, accompanied by a

policeman of Buliloan, Cebu on April 8, 1991.

That he consented to come to Manila to ask

forgiveness from Rosita Lim. That in

connection with this case, he executed an

affidavit on April 12, 1991, prepared by a

certain Atty. Perlas, a CIS personnel, and the

contents thereof were explained to him by

Rosita Lim before he signed the same before

Atty. Jose Tayo, a Notary Public, at Magnolia

House, Carriedo, Manila (Exhibits C and C-1).

That usually, it was the secretary of Mr. Tan

who accepted the items delivered to Ramon

Hardware. Further, he stated that the stolen

items from the warehouse were placed in a

sack and he talked to Mr. Tan first over the

phone before he delivered the spare parts. It

was Mr. Tan himself who accepted the stolen

items in the morning at about 7:00 to 8:00

oclock and paid P13,000.00 for them.

RAMON TAN, the accused, in exculpation,

stated that he is a businessman engaged in

selling hardware (marine spare parts) at 944

Espeleta Street, Sta. Cruz, Manila.

He denied having bought the stolen spare

parts worth P48,000.00 for he never talked

nor met Manuelito Mendez, the confessed

thief. That further the two (2) receipts

presented by Mrs. Lim are not under her

name and the other two (2) are under the

name of William Tan, the husband, all in all

amounting to P18,000.00. Besides, the

incident was not reported to the police

(Exhibits 1 to 1-g).

He likewise denied having talked to

Manuelito Mendez over the phone on the day

of the delivery of the stolen items and could

not have accepted the said items personally

for everytime (sic) goods are delivered to his

store, the same are being accepted by his

staff. It is not possible for him to be at his

office at about 7:00 to 8:00 oclock in the

morning, because he usually reported to his

office at 9:00 oclock. In connection with this

case, he executed a counter-affidavit

(Exhibits 2 and 2-a).[1]

On August 5, 1996, the trial court

rendered decision, the dispositive portion of

which reads:

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the

accused RAMON C. TAN is hereby found

guilty beyond reasonable doubt of violating

the Anti-Fencing Law of 1979, otherwise

known as Presidential Decree No. 1612, and

sentences him to suffer the penalty of

imprisonment of SIX (6) YEARS and ONE (1)

DAY to TEN (10) YEARS of prision mayor

and to indemnify Rosita Lim the value of the

stolen merchandise purchased by him in the

sum of P18,000.00.

Costs against the accused.

SO ORDERED.

Manila, Philippines, August 5, 1996.

After due proceedings, on January 29,

1998, the Court of Appeals rendered decision

finding no error in the judgment appealed

from, and affirming the same in toto.

In due time, petitioner filed with the

Court

of

Appeals

a

motion

for

reconsideration; however, on June 16, 1998,

the Court of Appeals denied the motion.

Hence, this petition.

The issue raised is whether or not the

prosecution has successfully established the

elements of fencing as against petitioner.[2]

We resolve

petitioner.

the

issue

in

favor

of

Fencing, as defined in Section 2 of P.D.

No. 1612 is the act of any person who, with

intent to gain for himself or for another, shall

buy, receive, possess, keep, acquire, conceal,

sell or dispose of, or shall buy and sell, or in

any manner deal in any article, item, object or

anything of value which he knows, or should

be known to him, to have been derived from

the proceeds of the crime of robbery or theft.

[3]

Robbery is the taking of personal

property belonging to another, with intent to

gain, by means of violence against or

intimidation of any person, or using force

upon things.[4]

(s/t) ZENAIDA R. DAGUNA

Judge

Petitioner appealed to the Court of

Appeals.

The crime of theft is committed if the

taking is without violence against or

intimidation of persons nor force upon

things.[5]

The law on fencing does not require the

accused to have participated in the criminal

design to commit, or to have been in any wise

involved in the commission of, the crime of

robbery or theft.[6]

Before the enactment of P. D. No. 1612 in

1979, the fence could only be prosecuted as

an accessory after the fact of robbery or theft,

as the term is defined in Article 19 of the

Revised Penal Code, but the penalty was light

as it was two (2) degrees lower than that

prescribed for the principal.[7]

2. The accused, who is not a principal or

accomplice in the commission of the crime of

robbery or theft, buys, receives, possesses,

keeps, acquires, conceals, sells or disposes, or

buys and sells, or in any manner deals in any

article, item, object or anything of value,

which has been derived from the proceeds of

the said crime;

3. The accused knows or should have known

that the said article, item, object or anything

of value has been derived from the proceeds

of the crime of robbery or theft; and

P. D. No. 1612 was enacted to impose

heavy penalties on persons who profit by the

effects of the crimes of robbery and theft.

Evidently, the accessory in the crimes of

robbery and theft could be prosecuted as such

under the Revised Penal Code or under P.D.

No. 1612. However, in the latter case, the

accused ceases to be a mere accessory but

becomes a principal in the crime of fencing.

Otherwise stated, the crimes of robbery and

theft, on the one hand, and fencing, on the

other, are separate and distinct offenses.

[8]

The State may thus choose to prosecute

him either under the Revised Penal Code or

P. D. No. 1612, although the preference for

the latter would seem inevitable considering

that fencing is malum prohibitum, and P. D.

No. 1612 creates a presumption of

fencing[9] and prescribes a higher penalty

based on the value of the property.[10]

4. There is on the part of the accused, intent

to gain for himself or for another.[11]

In Dizon-Pamintuan vs. People of the

Philippines, we set out the essential elements

of the crime of fencing as follows:

Complainant Rosita Lim testified that she

lost certain items and Manuelito Mendez

confessed that he stole those items and sold

them to the accused. However, Rosita Lim

never reported the theft or even loss to the

police. She admitted that after Manuelito

Mendez, her former employee, confessed to

1. A crime of robbery or theft has been

committed;

Consequently, the prosecution must

prove the guilt of the accused by establishing

the existence of all the elements of the crime

charged. [12]

Short of evidence establishing beyond

reasonable doubt the existence of the

essential elements of fencing, there can be no

conviction for such offense.[13] It is an ancient

principle of our penal system that no one

shall be found guilty of crime except upon

proof beyond reasonable doubt (Perez vs.

Sandiganbayan, 180 SCRA 9).[14]

In this case, what was the evidence of the

commission of theft independently of

fencing?

the unlawful taking of the items, she forgave

him, and did not prosecute him. Theft is a

public crime. It can be prosecuted de oficio,

or even without a private complainant, but it

cannot be without a victim. As complainant

Rosita Lim reported no loss, we cannot hold

for certain that there was committed a crime

of theft. Thus, the first element of the crime

of fencing is absent, that is, a crime of

robbery or theft has been committed.

There was no sufficient proof of the

unlawful taking of anothers property. True,

witness Mendez admitted in an extra-judicial

confession that he sold the boat parts he had

pilfered from complainant to petitioner.

However, an admission or confession

acknowledging guilt of an offense may be

given in evidence only against the person

admitting or confessing.[15] Even on this, if

given extra-judicially, the confessant must

have the assistance of counsel; otherwise, the

admission would be inadmissible in evidence

against the person so admitting.[16] Here, the

extra-judicial confession of witness Mendez

was not given with the assistance of counsel,

hence, inadmissible against the witness.

Neither may such extra-judicial confession be

considered evidence against accused.[17] There

must be corroboration by evidence of corpus

delicti to sustain a finding of guilt.[18] Corpus

delicti means the body or substance of the

crime, and, in its primary sense, refers to the

fact that the crime has been actually

committed.[19] The essential elements of theft

are (1) the taking of personal property; (2) the

property belongs to another; (3) the taking

away was done with intent of gain; (4) the

taking away was done without the consent of

the owner; and (5) the taking away is

accomplished

without

violence

or

intimidation against persons or force upon

things (U. S. vs. De Vera, 43 Phil. 1000).[20] In

theft, corpus delicti has two elements,

namely: (1) that the property was lost by the

owner, and (2) that it was lost by felonious

taking.[21] In this case, the theft was not

proved because complainant Rosita Lim did

not complain to the public authorities of the

felonious taking of her property. She sought

out her former employee Manuelito Mendez,

who confessed that he stole certain articles

from the warehouse of the complainant and

sold them to petitioner. Such confession is

insufficient to convict, without evidence

of corpus delicti.[22]

What is more, there was no showing at all

that the accused knew or should have known

that the very stolen articles were the ones

sold to him. One is deemed to know a

particular fact if he has the cognizance,

consciousness or awareness thereof, or is

aware of the existence of something, or has

the acquaintance with facts, or if he has

something within the minds grasp with

certitude and clarity. When knowledge of the

existence of a particular fact is an element of

an offense, such knowledge is established if a

person is aware of a high probability of its

existence unless he actually believes that it

does not exist. On the other hand, the words

should know denote the fact that a person of

reasonable prudence and intelligence would

ascertain the fact in performance of his duty

to another or would govern his conduct upon

assumption that such fact exists. Knowledge

refers to a mental state of awareness about a

fact. Since the court cannot penetrate the

mind of an accused and state with certainty

what is contained therein, it must determine

such knowledge with care from the overt acts

of that person. And given two equally

plausible states of cognition or mental

awareness, the court should choose the

one which sustains the constitutional

presumption of innocence.[23]

Without petitioner knowing that he

acquired stolen articles, he can not be guilty

of fencing.[24]

WHEREFORE, the Court REVERSES

and SETS ASIDE the decision of the Court of

Appeals in CA-G.R. CR. No. 20059 and

hereby ACQUITS petitioner of the offense

charged in Criminal Case No. 92-108222 of

the Regional Trial Court, Manila.

Costs de oficio.

SO ORDERED.

Consequently, the prosecution has failed

to establish the essential elements of fencing,

and thus petitioner is entitled to an acquittal.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Francisco v. PermkulDocument2 pagesFrancisco v. PermkulMika AurelioPas encore d'évaluation

- People Vs ListerioDocument1 pagePeople Vs Listeriojacaringal1Pas encore d'évaluation

- 18) Virgilio Del Rosario Et Al., vs. Court of AppealsDocument1 page18) Virgilio Del Rosario Et Al., vs. Court of AppealsAngelica YatcoPas encore d'évaluation

- People Vs SabalonesDocument3 pagesPeople Vs SabalonessjbloraPas encore d'évaluation

- VILLAREAL Vs People of The PhilippinesDocument1 pageVILLAREAL Vs People of The PhilippinesSheila RosettePas encore d'évaluation

- JAVIER Vs SANDIGANBAYANDocument2 pagesJAVIER Vs SANDIGANBAYANLoveAnnePas encore d'évaluation

- 7 People V AlfantaDocument1 page7 People V AlfantaDylanPas encore d'évaluation

- 161 Perez and Doria v. PT - T (Medina)Document5 pages161 Perez and Doria v. PT - T (Medina)Mikaela PamatmatPas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. 70481 December 11, 1992Document5 pagesG.R. No. 70481 December 11, 1992Rache BaodPas encore d'évaluation

- BANK OF AMERICA v. ArcDocument2 pagesBANK OF AMERICA v. ArcChariPas encore d'évaluation

- 8 - Yao Kee V Sy-Gonzales - Arts. 11 and 12Document2 pages8 - Yao Kee V Sy-Gonzales - Arts. 11 and 12Nelda EnriquezPas encore d'évaluation

- DIGEST - Reno V ACLU PDFDocument4 pagesDIGEST - Reno V ACLU PDFAgatha ApolinarioPas encore d'évaluation

- People v. Yanson-DumancasDocument20 pagesPeople v. Yanson-DumancasBea MarañonPas encore d'évaluation

- SANGALANG Vs IACpubcorpDocument2 pagesSANGALANG Vs IACpubcorpDerek C. EgallaPas encore d'évaluation

- Garcillano Vs HorDocument2 pagesGarcillano Vs HorDi ko alamPas encore d'évaluation

- People v. Esteban y MolinaDocument7 pagesPeople v. Esteban y MolinaZoe Kristeun GutierrezPas encore d'évaluation

- 105 People V DiscalsotaDocument4 pages105 People V DiscalsotaCharm CarreteroPas encore d'évaluation

- BPI V DandoDocument13 pagesBPI V DandoDandolph Tan100% (1)

- Characteristics of Criminal Law: Criminal Liability (Who May Incur?) Classes of FelonyDocument6 pagesCharacteristics of Criminal Law: Criminal Liability (Who May Incur?) Classes of FelonyJohn PatrickPas encore d'évaluation

- AdrianoDocument2 pagesAdrianovmanalo16Pas encore d'évaluation

- DIGEST - Hiyas Savings v. Acuña PDFDocument1 pageDIGEST - Hiyas Savings v. Acuña PDFJam ZaldivarPas encore d'évaluation

- People vs. DinolaDocument5 pagesPeople vs. Dinolanido12100% (1)

- People v. OanisDocument4 pagesPeople v. Oanisdaryll generynPas encore d'évaluation

- People vs. PasudagDocument3 pagesPeople vs. PasudagMil LoronoPas encore d'évaluation

- People V EstepanoDocument3 pagesPeople V EstepanoMarcie Denise Calimag AranetaPas encore d'évaluation

- 08 Tiu San V RepublicDocument2 pages08 Tiu San V RepublicPu Pujalte100% (1)

- CRIM 1 People v. DobleDocument2 pagesCRIM 1 People v. DobleNicole DeocarisPas encore d'évaluation

- People Vs CampuhanDocument2 pagesPeople Vs CampuhanFrancis Coronel Jr.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ernesto Garces v. People G.R. No. 173858Document8 pagesErnesto Garces v. People G.R. No. 173858BellePas encore d'évaluation

- First Division: Carpio, J.Document14 pagesFirst Division: Carpio, J.Emman CariñoPas encore d'évaluation

- Celerina J. Santos, V. Ricardo T. Santos: HanrobleslawDocument2 pagesCelerina J. Santos, V. Ricardo T. Santos: HanrobleslawKristelle IgnacioPas encore d'évaluation

- Art 11 CasesDocument26 pagesArt 11 CasesArnel MangilimanPas encore d'évaluation

- People V Echagaray, G.R. No. 117472Document9 pagesPeople V Echagaray, G.R. No. 117472JM CamposPas encore d'évaluation

- Bagatsing vs. RamirezDocument2 pagesBagatsing vs. RamirezGendale Am-isPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Digests: Topic Author Case Title GR No Tickler Date Doctrine FactsDocument2 pagesCase Digests: Topic Author Case Title GR No Tickler Date Doctrine Factsmichelle zatarainPas encore d'évaluation

- Villanueva vs. Ca BPI vs. POSADAS (Collector of Internal Revenue)Document5 pagesVillanueva vs. Ca BPI vs. POSADAS (Collector of Internal Revenue)Rafael AdanPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Digests CIR V CADocument2 pagesCase Digests CIR V CAEna Ross EscrupoloPas encore d'évaluation

- Legal Research PEOPLE Vs ERNESTO FRAGANTE Y AYUDA GR No. 182521 CASE DIGEST 2011Document25 pagesLegal Research PEOPLE Vs ERNESTO FRAGANTE Y AYUDA GR No. 182521 CASE DIGEST 2011Brenda de la Gente100% (1)

- Law116 A4 SanPabloVCIRDocument2 pagesLaw116 A4 SanPabloVCIRpolgasyPas encore d'évaluation

- 10.villanueva vs. CaDocument2 pages10.villanueva vs. CaSamuel John CahimatPas encore d'évaluation

- Del Castillo vs. TorrecampoDocument3 pagesDel Castillo vs. TorrecampoSherwin Anoba CabutijaPas encore d'évaluation

- People vs. TorrefielDocument2 pagesPeople vs. TorrefielKarlo KapunanPas encore d'évaluation

- Agbayani vs. PNBDocument2 pagesAgbayani vs. PNBRoyce PedemontePas encore d'évaluation

- People v. Jalosjos G.R. No. 132875-76, 3 February 2000Document10 pagesPeople v. Jalosjos G.R. No. 132875-76, 3 February 2000Dominic NoblezaPas encore d'évaluation

- Mining Act of 1995 PDFDocument12 pagesMining Act of 1995 PDFmartin 1984100% (1)

- GR L-135216Document13 pagesGR L-135216Louem GarceniegoPas encore d'évaluation

- Luis K. Lokin, JR Vs Commission On Elections G.R. Nos. 179431-32Document11 pagesLuis K. Lokin, JR Vs Commission On Elections G.R. Nos. 179431-32Wilbert ChongPas encore d'évaluation

- Calimutan v. PeopleDocument2 pagesCalimutan v. PeopleSamantha Ann T. TirthdasPas encore d'évaluation

- Statcon Finals ReviewerDocument30 pagesStatcon Finals ReviewerAyanna Noelle H. Villanueva100% (1)

- Avelino vs. Cuenca - Elect Its Own PresidentDocument3 pagesAvelino vs. Cuenca - Elect Its Own PresidentJP TolPas encore d'évaluation

- Hon. Sec. of Labor v. Panay Veterans SecurityDocument1 pageHon. Sec. of Labor v. Panay Veterans SecuritychachiPas encore d'évaluation

- People v. DobleDocument3 pagesPeople v. DobleGia DimayugaPas encore d'évaluation

- De Guzman v. PeopleDocument2 pagesDe Guzman v. PeopleRoger Pascual Cuaresma100% (1)

- Synopsis: ART. 70. Successive Service of Sentences. - When The Culprit Has To Serve Two or More PenaltiesDocument3 pagesSynopsis: ART. 70. Successive Service of Sentences. - When The Culprit Has To Serve Two or More PenaltiesCheala ManagayPas encore d'évaluation

- RPC Art 13 DigestsDocument45 pagesRPC Art 13 DigestsLouis MalaybalayPas encore d'évaluation

- Crim Art4 DigestDocument8 pagesCrim Art4 DigestAlexa Neri ValderamaPas encore d'évaluation

- EVANGELISTA VS SISTOZAdigestDocument2 pagesEVANGELISTA VS SISTOZAdigestEileenShiellaDialimas100% (1)

- CrimLaw Digest 2Document18 pagesCrimLaw Digest 2Ariane AquinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Vino V PeopleDocument2 pagesVino V PeopleJeon GarciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Viño Vs People, 178 SCRA 626, G.R. No. 84163, Oct. 19, 1989Document13 pagesViño Vs People, 178 SCRA 626, G.R. No. 84163, Oct. 19, 1989Gi NoPas encore d'évaluation

- Rene Callanta NotesDocument119 pagesRene Callanta NotesMarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Changing The Surname of A ChildDocument2 pagesChanging The Surname of A ChildMarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 Ways To Correct Error in Birth CertificateDocument2 pages2 Ways To Correct Error in Birth CertificateMarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Trail Smelter Case DigestDocument1 pageTrail Smelter Case DigestJulianPas encore d'évaluation

- Persons in AuthorityDocument9 pagesPersons in AuthorityMarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Above Income Statement Is Hereby Certified To Be True and Correct byDocument1 pageThe Above Income Statement Is Hereby Certified To Be True and Correct byMarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Primermpp PDFDocument4 pagesPrimermpp PDFMarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lawyer's OathDocument1 pageLawyer's OathKukoy PaktoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Heirs of Jose MaligasoDocument10 pagesHeirs of Jose MaligasoMarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- In Fortune MedicareDocument2 pagesIn Fortune MedicareMarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Consti2 - Privacy of CommunicationsDocument36 pagesConsti2 - Privacy of CommunicationsMarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- In Fortune MedicareDocument2 pagesIn Fortune MedicareMarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Uy vs. Land BankDocument2 pagesUy vs. Land BankMarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Esteban Pos PPRDocument18 pagesEsteban Pos PPRMarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lawyer's OathDocument1 pageLawyer's OathKukoy PaktoyPas encore d'évaluation

- DDDDocument50 pagesDDDMarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Obli CaseDocument17 pagesObli CaseMarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Due Process and Eminent DomainDocument4 pagesDue Process and Eminent DomainMarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- ObliDocument19 pagesObliMarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Digest For 2009 Case - British American Tobacco V CamachoDocument1 pageDigest For 2009 Case - British American Tobacco V Camachocookbooks&lawbooks100% (1)

- Participant Information Sheet: To Be Accomplished by The ParticipantDocument1 pageParticipant Information Sheet: To Be Accomplished by The ParticipantMarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Socleg 1Document89 pagesSocleg 1MarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Oct 18 Labstan Part 2Document1 pageOct 18 Labstan Part 2MarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Probation Additional DicsussionDocument4 pagesProbation Additional DicsussionMarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- RA 8042 With RA 10022Document16 pagesRA 8042 With RA 10022MarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Envi Law Notes FINALDocument55 pagesEnvi Law Notes FINALMarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Del Castillo vs. PeopleDocument4 pagesDel Castillo vs. PeopleMarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- New SongsDocument10 pagesNew SongsMarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Section 4. Application. - All Medium and Large Scale Business Enterprises UsedDocument3 pagesSection 4. Application. - All Medium and Large Scale Business Enterprises UsedMarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Implementing Rules of Book ViDocument8 pagesImplementing Rules of Book ViMarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Syllabus - Philosophy of Law - Minnesota 2013Document6 pagesSyllabus - Philosophy of Law - Minnesota 2013MitchPas encore d'évaluation

- Contract LawDocument64 pagesContract LawOBERT MASALILAPas encore d'évaluation

- Legal Separation in The Philippine SettingDocument10 pagesLegal Separation in The Philippine SettingRegina Via G. GarciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurisprudence IDocument128 pagesJurisprudence IAnique MughalPas encore d'évaluation

- Relationship Between Law and Morality or EthicsDocument9 pagesRelationship Between Law and Morality or Ethicsokello100% (2)

- Comparison of Adversarial and Inquisitorial System of Criminal JusticeDocument16 pagesComparison of Adversarial and Inquisitorial System of Criminal JusticeShubhrajit SahaPas encore d'évaluation

- FINLEY Breaking Womens Silence in LawDocument25 pagesFINLEY Breaking Womens Silence in LawMadz BuPas encore d'évaluation

- 4people v. MadsaliDocument16 pages4people v. MadsaliquasideliksPas encore d'évaluation

- 42 Usc 1983 Bad Faith AuthoritiesDocument254 pages42 Usc 1983 Bad Faith Authoritiesdavidchey4617100% (1)

- Assignment - Legal Environment of BusinessDocument6 pagesAssignment - Legal Environment of BusinessShakeeb Hashmi100% (1)

- Elements of Malicious ProsecutionDocument22 pagesElements of Malicious ProsecutionAJITABHPas encore d'évaluation

- Jacob Mathews Case CommentDocument6 pagesJacob Mathews Case CommentManideepa Chaudhury100% (1)

- Ethics FinalDocument27 pagesEthics FinalMarianne AndresPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes in Torts (Jurado, 2009)Document4 pagesNotes in Torts (Jurado, 2009)YanilyAnnVldzPas encore d'évaluation

- Scribd Submission 1 - Kant and FreedomDocument12 pagesScribd Submission 1 - Kant and FreedomJorel ChanPas encore d'évaluation

- Book I Part 2Document23 pagesBook I Part 2brendamanganaanPas encore d'évaluation

- Eternal LawDocument34 pagesEternal LawMaam PreiPas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. 168539 March 25, 2014 People of The Philippines, Petitioner, HENRY T. GO, RespondentDocument7 pagesG.R. No. 168539 March 25, 2014 People of The Philippines, Petitioner, HENRY T. GO, RespondentGen CabrillasPas encore d'évaluation

- Analytical School of Jurisprudence: Positivism in LawDocument7 pagesAnalytical School of Jurisprudence: Positivism in LawDEEPAKPas encore d'évaluation

- The Law of Evidenc1Document121 pagesThe Law of Evidenc1Gigi MungaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Law of Torts & Consumer Protection Act Renaissance Law College NotesDocument76 pagesLaw of Torts & Consumer Protection Act Renaissance Law College NotesAnjana NairPas encore d'évaluation

- Nicola Lacey - Unspeakable Subjects - Feminist Essays in Legal and Social Theory (1998)Document284 pagesNicola Lacey - Unspeakable Subjects - Feminist Essays in Legal and Social Theory (1998)Dharaba ZaidonPas encore d'évaluation

- Jeffrey Jessie: Recognising TranssexualsDocument16 pagesJeffrey Jessie: Recognising Transsexualsjustice for sistersPas encore d'évaluation

- Torts & Damages SyllabusDocument2 pagesTorts & Damages SyllabusNeil Davis BulanPas encore d'évaluation

- Law As Commands: Bentham and AustinDocument5 pagesLaw As Commands: Bentham and AustinRANDAN SADIQPas encore d'évaluation

- Specialty: Electrical Poweer Systerm (E.P.S) Institution: Fonab Polytecnic COURS: LAW Assignment NamesDocument5 pagesSpecialty: Electrical Poweer Systerm (E.P.S) Institution: Fonab Polytecnic COURS: LAW Assignment NamesKindzeka Darius mbidzenyuyPas encore d'évaluation

- Legal MethodDocument23 pagesLegal Methodnayan96.mdgrPas encore d'évaluation

- PenaltyDocument63 pagesPenaltyMario Manolito S. Del ValPas encore d'évaluation

- Kuruma, Son of Kaniu V R (1955) AC 197, (195Document3 pagesKuruma, Son of Kaniu V R (1955) AC 197, (195nur_amanina_7100% (3)

- Evid Tranquil LectureDocument5 pagesEvid Tranquil LectureAleezah Gertrude R RegadoPas encore d'évaluation