Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Persons - 1 Wassmer V Velez

Transféré par

Yu Babylan0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

37 vues2 pagesFull Text

Titre original

Persons_1 Wassmer v Velez

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

DOCX, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentFull Text

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme DOCX, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

37 vues2 pagesPersons - 1 Wassmer V Velez

Transféré par

Yu BabylanFull Text

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme DOCX, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 2

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

the proceedings the possibility of arriving at an amicable

settlement." It added that should any of them fail to appear "the

petition for relief and the opposition thereto will be deemed

submitted for resolution."

EN BANC

G.R. No. L-20089

December 26, 1964

BEATRIZ P. WASSMER, plaintiff-appellee,

vs.

FRANCISCO X. VELEZ, defendant-appellant.

Jalandoni & Jamir for defendant-appellant.

Samson S. Alcantara for plaintiff-appellee.

BENGZON, J.P., J.:

The facts that culminated in this case started with dreams and

hopes, followed by appropriate planning and serious

endeavors, but terminated in frustration and, what is worse,

complete public humiliation.

Francisco X. Velez and Beatriz P. Wassmer, following their

mutual promise of love, decided to get married and set

September 4, 1954 as the big day. On September 2, 1954

Velez left this note for his bride-to-be:

Dear Bet

Will have to postpone wedding My mother

opposes it. Am leaving on the Convair today.

Please do not ask too many people about the

reason why That would only create a

scandal.

Paquing

But the next day, September 3, he sent her the following

telegram:

NOTHING CHANGED REST ASSURED

RETURNING VERY SOON APOLOGIZE

MAMA PAPA LOVE .

PAKING

Thereafter Velez did not appear nor was he heard from again.

Sued by Beatriz for damages, Velez filed no answer and was

declared in default. Plaintiff adduced evidence before the clerk

of court as commissioner, and on April 29, 1955, judgment was

rendered ordering defendant to pay plaintiff P2,000.00 as

actual damages; P25,000.00 as moral and exemplary

damages; P2,500.00 as attorney's fees; and the costs.

On June 21, 1955 defendant filed a "petition for relief from

orders, judgment and proceedings and motion for new trial and

reconsideration." Plaintiff moved to strike it cut. But the court,

on August 2, 1955, ordered the parties and their attorneys to

appear before it on August 23, 1955 "to explore at this stage of

On August 23, 1955 defendant failed to appear before court.

Instead, on the following day his counsel filed a motion to defer

for two weeks the resolution on defendants petition for relief.

The counsel stated that he would confer with defendant in

Cagayan de Oro City the latter's residence on the

possibility of an amicable element. The court granted two

weeks counted from August 25, 1955.

Plaintiff manifested on June 15, 1956 that the two weeks given

by the court had expired on September 8, 1955 but that

defendant and his counsel had failed to appear.

Another chance for amicable settlement was given by the court

in its order of July 6, 1956 calling the parties and their attorneys

to appear on July 13, 1956. This time. however, defendant's

counsel informed the court that chances of settling the case

amicably were nil.

On July 20, 1956 the court issued an order denying defendant's

aforesaid petition. Defendant has appealed to this Court. In his

petition of June 21, 1955 in the court a quo defendant alleged

excusable negligence as ground to set aside the judgment by

default. Specifically, it was stated that defendant filed no

answer in the belief that an amicable settlement was being

negotiated.

A petition for relief from judgment on grounds of fraud,

accident, mistake or excusable negligence, must be duly

supported by an affidavit of merits stating facts constituting a

valid defense. (Sec. 3, Rule 38, Rules of Court.) Defendant's

affidavit of merits attached to his petition of June 21, 1955

stated: "That he has a good and valid defense against plaintiff's

cause of action, his failure to marry the plaintiff as scheduled

having been due to fortuitous event and/or circumstances

beyond his control." An affidavit of merits like this stating mere

conclusions or opinions instead of facts is not valid. (Cortes vs.

Co Bun Kim, L-3926, Oct. 10, 1951; Vaswani vs. P. Tarrachand

Bros., L-15800, December 29, 1960.)

Defendant, however, would contend that the affidavit of merits

was in fact unnecessary, or a mere surplusage, because the

judgment sought to be set aside was null and void, it having

been based on evidence adduced before the clerk of court. In

Province of Pangasinan vs. Palisoc, L-16519, October 30,

1962, this Court pointed out that the procedure of designating

the clerk of court as commissioner to receive evidence is

sanctioned by Rule 34 (now Rule 33) of the Rules of Court.

Now as to defendant's consent to said procedure, the same did

not have to be obtained for he was declared in default and thus

had no standing in court (Velez vs. Ramas, 40 Phil. 787; Alano

vs. Court of First Instance, L-14557, October 30, 1959).

In support of his "motion for new trial and reconsideration,"

defendant asserts that the judgment is contrary to law. The

reason given is that "there is no provision of the Civil Code

authorizing" an action for breach of promise to marry. Indeed,

our ruling in Hermosisima vs. Court of Appeals (L-14628, Sept.

30, 1960), as reiterated in Estopa vs. Biansay (L-14733, Sept.

30, 1960), is that "mere breach of a promise to marry" is not an

actionable wrong. We pointed out that Congress deliberately

eliminated from the draft of the new Civil Code the provisions

that would have it so.

It must not be overlooked, however, that the extent to which

acts not contrary to law may be perpetrated with impunity, is

not limitless for Article 21 of said Code provides that "any

person who wilfully causes loss or injury to another in a manner

that is contrary to morals, good customs or public policy shall

compensate the latter for the damage."

The record reveals that on August 23, 1954 plaintiff and

defendant applied for a license to contract marriage, which was

subsequently issued (Exhs. A, A-1). Their wedding was set for

September 4, 1954. Invitations were printed and distributed to

relatives, friends and acquaintances (Tsn., 5; Exh. C). The

bride-to-be's trousseau, party drsrses and other apparel for the

important occasion were purchased (Tsn., 7-8). Dresses for the

maid of honor and the flower girl were prepared. A matrimonial

bed, with accessories, was bought. Bridal showers were given

and gifts received (Tsn., 6; Exh. E). And then, with but two days

before the wedding, defendant, who was then 28 years old,:

simply left a note for plaintiff stating: "Will have to postpone

wedding My mother opposes it ... " He enplaned to his home

city in Mindanao, and the next day, the day before the wedding,

he wired plaintiff: "Nothing changed rest assured returning

soon." But he never returned and was never heard from again.

Surely this is not a case of mere breach of promise to marry. As

stated, mere breach of promise to marry is not an actionable

wrong. But to formally set a wedding and go through all the

above-described preparation and publicity, only to walk out of it

when the matrimony is about to be solemnized, is quite

different. This is palpably and unjustifiably contrary to good

customs for which defendant must be held answerable in

damages in accordance with Article 21 aforesaid.

Defendant urges in his afore-stated petition that the damages

awarded were excessive. No question is raised as to the award

of actual damages. What defendant would really assert

hereunder is that the award of moral and exemplary damages,

in the amount of P25,000.00, should be totally eliminated.

Per express provision of Article 2219 (10) of the New Civil

Code, moral damages are recoverable in the cases mentioned

in Article 21 of said Code. As to exemplary damages, defendant

contends that the same could not be adjudged against him

because under Article 2232 of the New Civil Code the condition

precedent is that "the defendant acted in a wanton, fraudulent,

reckless, oppressive, or malevolent manner." The argument is

devoid of merit as under the above-narrated circumstances of

this case defendant clearly acted in a "wanton ... , reckless

[and] oppressive manner." This Court's opinion, however, is that

considering the particular circumstances of this case,

P15,000.00 as moral and exemplary damages is deemed to be

a reasonable award.

PREMISES CONSIDERED, with the above-indicated

modification, the lower court's judgment is hereby affirmed, with

costs.

Bengzon, C.J., Bautista Angelo, Reyes, J.B.L., Barrera,

Paredes, Dizon, Regala, Makalintal, and Zaldivar, JJ.,concur.

Facts:

Francisco Velez and Beatriz Wassmer,

following their mutual promise of love decided to get

married on September 4, 1954. On the day of the

supposed marriage, Velez left a note for his bride-to-be

that day to postpone their wedding because his mother

opposes it. Therefore, Velez did not appear and was not

heard from again.

Beatriz sued Velez for damages and Velez

failed to answer and was declared in default.

Judgement was rendered ordering the defendant to pay

plaintiff P2.000 as actual damages P25,000 as moral

and exemplary damages, P2,500 as attorneys fees.

Later, an attempt by the Court for amicable

settlement was given chance but failed, thereby

rendered judgment hence this appeal.

Issue:

Whether or not breach of promise to marry is

an actionable wrong in this case.

Held:

Ordinarily, a mere breach of promise to marry

is not an actionable wrong. But formally set a wedding

and go through all the necessary preparations and

publicity and only to walk out of it when matrimony is

about to be solemnized, is quite different. This is

palpable and unjustifiable to good customs which holds

liability in accordance with Art. 21 on the New Civil

Code.

When a breach of promise to marry is

actionable under the same, moral and exemplary

damages may not be awarded when it is proven that

the defendanr clearly acted in wanton, reckless and

oppressive manner.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Pacete V CariagaDocument1 pagePacete V CariagaMark Joseph Pedroso CendanaPas encore d'évaluation

- People vs. de VeraDocument1 pagePeople vs. de VeraeirojoycePas encore d'évaluation

- Adoption ChartDocument4 pagesAdoption ChartSui100% (1)

- Arcaba V Vda. BatocaelDocument10 pagesArcaba V Vda. Batocaelyannie11Pas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. 128096 Lacson PDFDocument10 pagesG.R. No. 128096 Lacson PDFShariPas encore d'évaluation

- BACANI Vs NAcocoDocument3 pagesBACANI Vs NAcocoReyes CousinsPas encore d'évaluation

- PCIBvBALMACEDA GR158143 (2011) (CD) (FT)Document13 pagesPCIBvBALMACEDA GR158143 (2011) (CD) (FT)PierrePas encore d'évaluation

- Art. 13 - US Vs Ampar GR 12883 Nov. 26, 1917Document2 pagesArt. 13 - US Vs Ampar GR 12883 Nov. 26, 1917Lu CasPas encore d'évaluation

- Estonina Vs CADocument4 pagesEstonina Vs CAColleen Fretzie Laguardia NavarroPas encore d'évaluation

- QUEZON CITY PTCA FEDERATION Vs DepEd GR 188720Document2 pagesQUEZON CITY PTCA FEDERATION Vs DepEd GR 188720Ronnie Garcia Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Diong Bi Chu V Ca PDFDocument3 pagesDiong Bi Chu V Ca PDFTrishalyVienBaslotPas encore d'évaluation

- Abra Valley College Inc Vs Aquino (SUMMARY)Document2 pagesAbra Valley College Inc Vs Aquino (SUMMARY)ian clark MarinduquePas encore d'évaluation

- Bayot v. CA (G.R. Nos. 155635, 163979 November 7, 2008)Document14 pagesBayot v. CA (G.R. Nos. 155635, 163979 November 7, 2008)Hershey Delos SantosPas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. 157649Document2 pagesG.R. No. 157649Noel Christopher G. BellezaPas encore d'évaluation

- Fam RealDocument6 pagesFam RealTechnical 2016Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sabalones vs. CADocument7 pagesSabalones vs. CABea CapePas encore d'évaluation

- Pilapil vs. Hon. Ibay-SomeraDocument8 pagesPilapil vs. Hon. Ibay-SomeraJane Dela CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- Aberca v. Fabian-Ver, GR L-69866, 15 April 1988, en Banc, Yap (J)Document3 pagesAberca v. Fabian-Ver, GR L-69866, 15 April 1988, en Banc, Yap (J)Latjing SolimanPas encore d'évaluation

- Decision in Criminal Case No. SB-28361Document7 pagesDecision in Criminal Case No. SB-28361Choi ChoiPas encore d'évaluation

- 7 Gandionco vs. PenarandaDocument9 pages7 Gandionco vs. PenarandaRaiya AngelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Kuenzle & Streiff, Inc., vs. The Collector of Internal RevenueDocument7 pagesKuenzle & Streiff, Inc., vs. The Collector of Internal RevenueVincent OngPas encore d'évaluation

- PERSONS (De Roy vs. Court of Appeals 157 SCRA 757)Document1 pagePERSONS (De Roy vs. Court of Appeals 157 SCRA 757)Joseph TheThirdPas encore d'évaluation

- Sumulong v. ComelecDocument5 pagesSumulong v. ComelecHaniyyah FtmPas encore d'évaluation

- Herrera v. COMELECDocument5 pagesHerrera v. COMELECmisterdodiPas encore d'évaluation

- PFR - Rambaua v. RambauaDocument15 pagesPFR - Rambaua v. Rambauadenver41Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chavez Vs JBC en Banc G.R. No. 202242 April 16, 2013Document29 pagesChavez Vs JBC en Banc G.R. No. 202242 April 16, 2013herbs22225847Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bayot V Ca Gr. No 155635 & 163979Document9 pagesBayot V Ca Gr. No 155635 & 163979Ako Si Paula MonghitPas encore d'évaluation

- 94 Mendoza Vs VillasDocument5 pages94 Mendoza Vs VillasroyalwhoPas encore d'évaluation

- Republic v. Manalo, GR No. 221029 April 24, 2018Document12 pagesRepublic v. Manalo, GR No. 221029 April 24, 2018Ashley Kate PatalinjugPas encore d'évaluation

- People vs. RosenthalDocument2 pagesPeople vs. RosenthalJulius Robert JuicoPas encore d'évaluation

- Pimentel V Pimentel G.R. No. 172060, September 13, 2010, CJ Carpio - Prejudicial QuestionDocument2 pagesPimentel V Pimentel G.R. No. 172060, September 13, 2010, CJ Carpio - Prejudicial QuestionCarl AngeloPas encore d'évaluation

- Asjbdaksbjdkabskd in Re AgorsinoDocument2 pagesAsjbdaksbjdkabskd in Re AgorsinoAnonymous ksnMBh2mnPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 Republic V Judge of CFI of Rizal G.R. No. L-35919Document3 pages2 Republic V Judge of CFI of Rizal G.R. No. L-35919SDN HelplinePas encore d'évaluation

- Manzano V SanchezDocument1 pageManzano V SanchezERVIN SAGUNPas encore d'évaluation

- Suplico V NEDADocument6 pagesSuplico V NEDARZ ZamoraPas encore d'évaluation

- Liam Law vs. Olympic Sawmill Co.Document2 pagesLiam Law vs. Olympic Sawmill Co.ESS PORT OF LEGAZPI CPD-ESSPas encore d'évaluation

- Santero v. CFI of CaviteDocument2 pagesSantero v. CFI of CaviteFritz Frances DaniellePas encore d'évaluation

- Joya vs. PCGG Case DIgestDocument2 pagesJoya vs. PCGG Case DIgestIreen ZeePas encore d'évaluation

- Antonio Valdez v. RTC QC and Consuelo Gomez-ValdezDocument2 pagesAntonio Valdez v. RTC QC and Consuelo Gomez-ValdezSamuel John CahimatPas encore d'évaluation

- Yu Oh v. CADocument7 pagesYu Oh v. CAAgapito DuquePas encore d'évaluation

- LINA CALILAP-ASMERON, Petitioner vs. Development Bank of The Philippines, RespondentsDocument3 pagesLINA CALILAP-ASMERON, Petitioner vs. Development Bank of The Philippines, RespondentsDee SalvatierraPas encore d'évaluation

- De Ocampo Vs Florenciano DigestDocument5 pagesDe Ocampo Vs Florenciano DigestDanielle AlonzoPas encore d'évaluation

- AFP v. YAHONDocument4 pagesAFP v. YAHONJM GuevarraPas encore d'évaluation

- Ponente: Carpio-Morales, JDocument15 pagesPonente: Carpio-Morales, JCristelle Elaine ColleraPas encore d'évaluation

- Case DigestDocument9 pagesCase DigestAngelica Joyce Visaya IgnacioPas encore d'évaluation

- Aaa Vs BBB GR 212448Document6 pagesAaa Vs BBB GR 212448Jomar TenezaPas encore d'évaluation

- CIR Vs Lingayen 164 SCRA 27Document4 pagesCIR Vs Lingayen 164 SCRA 27Atty JV Abuel0% (1)

- Republic VS DayotDocument1 pageRepublic VS DayotbowybowyPas encore d'évaluation

- Delgado Vs HRETDocument7 pagesDelgado Vs HRETBrylle DeeiahPas encore d'évaluation

- Arigo V SwiftDocument2 pagesArigo V SwiftJawwada Pandapatan MacatangcopPas encore d'évaluation

- NicaDocument6 pagesNicacloudPas encore d'évaluation

- People Vs Perfecto 43 Phil 887Document5 pagesPeople Vs Perfecto 43 Phil 887filamiecacdacPas encore d'évaluation

- CASE 248 - People of The Philippines Vs SagunDocument3 pagesCASE 248 - People of The Philippines Vs Sagunbernadeth ranolaPas encore d'évaluation

- Morales v. Subido - 27 Scra 131 (1969)Document4 pagesMorales v. Subido - 27 Scra 131 (1969)Gol LumPas encore d'évaluation

- Fujiki Vs Marinay 700 SCRA 69Document20 pagesFujiki Vs Marinay 700 SCRA 69RaymondPas encore d'évaluation

- 7.2 Proclamation No. 58, S. 1987 - Official Gazette of The Republic of The PhilippinesDocument2 pages7.2 Proclamation No. 58, S. 1987 - Official Gazette of The Republic of The Philippinescharles batagaPas encore d'évaluation

- 50 Pilapil vs. Ibay-Somera 174 SCRA 653Document1 page50 Pilapil vs. Ibay-Somera 174 SCRA 653G-one PaisonesPas encore d'évaluation

- Political Law Preliminaries ReviewerDocument23 pagesPolitical Law Preliminaries ReviewerBallin BalgruufPas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. L-20089 Wassmer Vs VelezDocument4 pagesG.R. No. L-20089 Wassmer Vs VelezPJAPas encore d'évaluation

- Supreme Court: Jalandoni & Jamir For Defendant-Appellant. Samson S. Alcantara For Plaintiff-AppelleeDocument7 pagesSupreme Court: Jalandoni & Jamir For Defendant-Appellant. Samson S. Alcantara For Plaintiff-AppelleeGuinevere RaymundoPas encore d'évaluation

- HM PrelimsDocument9 pagesHM PrelimsYu BabylanPas encore d'évaluation

- Classroom Policies: Fundamentals of Accountancy - 2nd Semester, AY 2016 - 2017Document5 pagesClassroom Policies: Fundamentals of Accountancy - 2nd Semester, AY 2016 - 2017Yu BabylanPas encore d'évaluation

- Course Outline - Human Rights Law (2016-2017)Document2 pagesCourse Outline - Human Rights Law (2016-2017)Yu BabylanPas encore d'évaluation

- University of ST La Salle College of Business and Accountancy Bacolod City Accounting 1 - HM Midterm Exam AY 2015-2016, 1 SemesterDocument6 pagesUniversity of ST La Salle College of Business and Accountancy Bacolod City Accounting 1 - HM Midterm Exam AY 2015-2016, 1 SemesterYu BabylanPas encore d'évaluation

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Fin1 Eq2 BsatDocument1 pageFin1 Eq2 BsatYu BabylanPas encore d'évaluation

- IDS RemedialExamsDocument1 pageIDS RemedialExamsYu BabylanPas encore d'évaluation

- Answers To Hw2 - Baba2 FinanceDocument2 pagesAnswers To Hw2 - Baba2 FinanceYu BabylanPas encore d'évaluation

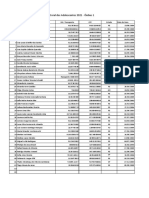

- Chapter 17 Financial Planning and ForecastingDocument39 pagesChapter 17 Financial Planning and ForecastingYu BabylanPas encore d'évaluation

- FIN1S Prelim ExamDocument7 pagesFIN1S Prelim ExamYu BabylanPas encore d'évaluation

- Cornell Media LunchDocument12 pagesCornell Media LunchYu BabylanPas encore d'évaluation

- Lindsay, Inc. Statement of Cash Flows For Year Ended December 31, Year 4 OperationsDocument1 pageLindsay, Inc. Statement of Cash Flows For Year Ended December 31, Year 4 OperationsYu BabylanPas encore d'évaluation

- Cash BudgetDocument2 pagesCash BudgetYu BabylanPas encore d'évaluation

- Baba Eq3 AnswersDocument4 pagesBaba Eq3 AnswersYu BabylanPas encore d'évaluation

- Baba2b Eq3Document2 pagesBaba2b Eq3Yu BabylanPas encore d'évaluation

- College of Business and AccountancyDocument2 pagesCollege of Business and AccountancyYu BabylanPas encore d'évaluation

- Ross, Selph, Carrascoso and Janda For Appellants. Delgado and Flores For AppelleeDocument15 pagesRoss, Selph, Carrascoso and Janda For Appellants. Delgado and Flores For AppelleeYu BabylanPas encore d'évaluation

- Partnership CasesDocument29 pagesPartnership CasesYu BabylanPas encore d'évaluation

- Pip Assessment GuideDocument155 pagesPip Assessment Guideb0bsp4mPas encore d'évaluation

- The New Rich in AsiaDocument31 pagesThe New Rich in AsiaIrdinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Form I-129F - BRANDON - NATALIADocument13 pagesForm I-129F - BRANDON - NATALIAFelipe AmorosoPas encore d'évaluation

- Christmas Pop-Up Card PDFDocument6 pagesChristmas Pop-Up Card PDFcarlosvazPas encore d'évaluation

- Solution and AnswerDocument4 pagesSolution and AnswerMicaela EncinasPas encore d'évaluation

- 7 Principles or 7 CDocument5 pages7 Principles or 7 Cnimra mehboobPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson Agreement Pronoun Antecedent PDFDocument2 pagesLesson Agreement Pronoun Antecedent PDFAndrea SPas encore d'évaluation

- 11 Its A Magical World - Bill WattersonDocument166 pages11 Its A Magical World - Bill Wattersonapi-560386898100% (8)

- E3 - Mock Exam Pack PDFDocument154 pagesE3 - Mock Exam Pack PDFMuhammadUmarNazirChishtiPas encore d'évaluation

- VoterListweb2016-2017 81Document1 pageVoterListweb2016-2017 81ShahzadPas encore d'évaluation

- The Role of Women in Trade Unions and Nation BuildingDocument18 pagesThe Role of Women in Trade Unions and Nation BuildingSneha KanitCar Kango100% (1)

- S No Clause No. Existing Clause/ Description Issues Raised Reply of NHAI Pre-Bid Queries Related To Schedules & DCADocument10 pagesS No Clause No. Existing Clause/ Description Issues Raised Reply of NHAI Pre-Bid Queries Related To Schedules & DCAarorathevipulPas encore d'évaluation

- Notice: Native American Human Remains, Funerary Objects Inventory, Repatriation, Etc.: Cosumnes River College, Sacramento, CADocument2 pagesNotice: Native American Human Remains, Funerary Objects Inventory, Repatriation, Etc.: Cosumnes River College, Sacramento, CAJustia.comPas encore d'évaluation

- Chinua Achebe: Dead Men's PathDocument2 pagesChinua Achebe: Dead Men's PathSalve PetilunaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2b22799f-f7c1-4280-9274-8c59176f78b6Document190 pages2b22799f-f7c1-4280-9274-8c59176f78b6Andrew Martinez100% (1)

- Nurlilis (Tgs. Bhs - Inggris. Chapter 4)Document5 pagesNurlilis (Tgs. Bhs - Inggris. Chapter 4)Latifa Hanafi100% (1)

- Are You ... Already?: BIM ReadyDocument8 pagesAre You ... Already?: BIM ReadyShakti NagrarePas encore d'évaluation

- Bung Tomo InggrisDocument4 pagesBung Tomo Inggrissyahruladiansyah43Pas encore d'évaluation

- Seven Lamps of AdvocacyDocument4 pagesSeven Lamps of AdvocacyMagesh Vaiyapuri100% (1)

- Total Gallium JB15939XXDocument18 pagesTotal Gallium JB15939XXAsim AliPas encore d'évaluation

- Berkshire Hathaway Inc.: United States Securities and Exchange CommissionDocument48 pagesBerkshire Hathaway Inc.: United States Securities and Exchange CommissionTu Zhan LuoPas encore d'évaluation

- GS Mains PYQ Compilation 2013-19Document159 pagesGS Mains PYQ Compilation 2013-19Xman ManPas encore d'évaluation

- Reaserch ProstitutionDocument221 pagesReaserch ProstitutionAron ChuaPas encore d'évaluation

- Become A Living God - 7 Steps For Using Spirit Sigils To Get Anything PDFDocument10 pagesBecome A Living God - 7 Steps For Using Spirit Sigils To Get Anything PDFVas Ra25% (4)

- Battletech BattleValueTables3.0 PDFDocument25 pagesBattletech BattleValueTables3.0 PDFdeitti333Pas encore d'évaluation

- Risk AssessmentDocument11 pagesRisk AssessmentRutha KidanePas encore d'évaluation

- Gillette vs. EnergizerDocument5 pagesGillette vs. EnergizerAshish Singh RainuPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Project Report - Keiretsu: Topic Page NoDocument10 pagesFinal Project Report - Keiretsu: Topic Page NoRevatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 5A - PartnershipsDocument6 pagesChapter 5A - PartnershipsRasheed AhmadPas encore d'évaluation

- Coral Dos Adolescentes 2021 - Ônibus 1: Num Nome RG / Passaporte CPF Estado Data de NascDocument1 pageCoral Dos Adolescentes 2021 - Ônibus 1: Num Nome RG / Passaporte CPF Estado Data de NascGabriel Kuhs da RosaPas encore d'évaluation