Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

3 Evangelista & Co. vs. Abad Santos PDF

Transféré par

agnatgaTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

3 Evangelista & Co. vs. Abad Santos PDF

Transféré par

agnatgaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

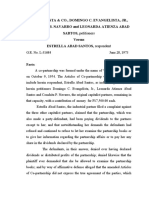

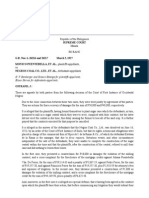

G.R. No.

L-31684 June 28, 1973

EVANGELISTA & CO., DOMINGO C. EVANGELISTA, JR., CONCHITA

B. NAVARRO and LEONARDA ATIENZA ABAD SABTOS, petitioners,

vs.

ESTRELLA ABAD SANTOS, respondent.

Leonardo Abola for petitioners.

Baisas, Alberto & Associates for respondent.

MAKALINTAL, J.:

On October 9, 1954 a co-partnership was formed under the name of

"Evangelista & Co." On June 7, 1955 the Articles of Co-partnership was

amended as to include herein respondent, Estrella Abad Santos, as

industrial partner, with herein petitioners Domingo C. Evangelista, Jr.,

Leonardo Atienza Abad Santos and Conchita P. Navarro, the original

capitalist partners, remaining in that capacity, with a contribution of

P17,500 each. The amended Articles provided, inter alia, that "the

contribution of Estrella Abad Santos consists of her industry being an

industrial partner", and that the profits and losses "shall be divided and

distributed among the partners ... in the proportion of 70% for the first three

partners, Domingo C. Evangelista, Jr., Conchita P. Navarro and Leonardo

Atienza Abad Santos to be divided among them equally; and 30% for the

fourth partner Estrella Abad Santos."

On December 17, 1963 herein respondent filed suit against the three other

partners in the Court of First Instance of Manila, alleging that the

partnership, which was also made a party-defendant, had been paying

dividends to the partners except to her; and that notwithstanding her

demands the defendants had refused and continued to refuse and let her

examine the partnership books or to give her information regarding the

partnership affairs to pay her any share in the dividends declared by the

partnership. She therefore prayed that the defendants be ordered to render

accounting to her of the partnership business and to pay her

corresponding share in the partnership profits after such accounting, plus

attorney's fees and costs.

The defendants, in their answer, denied ever having declared dividends or

distributed profits of the partnership; denied likewise that the plaintiff ever

demanded that she be allowed to examine the partnership books; and

byway of affirmative defense alleged that the amended Articles of Copartnership did not express the true agreement of the parties, which was

that the plaintiff was not an industrial partner; that she did not in fact

contribute industry to the partnership; and that her share of 30% was to be

based on the profits which might be realized by the partnership only until

full payment of the loan which it had obtained in December, 1955 from the

Rehabilitation Finance Corporation in the sum of P30,000, for which the

plaintiff had signed a promisory note as co-maker and mortgaged her

property as security.

The parties are in agreement that the main issue in this case is "whether

the plaintiff-appellee (respondent here) is an industrial partner as claimed

by her or merely a profit sharer entitled to 30% of the net profits that may

be realized by the partnership from June 7, 1955 until the mortgage loan

from the Rehabilitation Finance Corporation shall be fully paid, as claimed

by appellants (herein petitioners)." On that issue the Court of First Instance

found for the plaintiff and rendered judgement "declaring her an industrial

partner of Evangelista & Co.; ordering the defendants to render an

accounting of the business operations of the (said) partnership ... from

June 7, 1955; to pay the plaintiff such amounts as may be due as her

share in the partnership profits and/or dividends after such an accounting

has been properly made; to pay plaintiff attorney's fees in the sum of

P2,000.00 and the costs of this suit."

The defendants appealed to the Court of Appeals, which thereafter

affirmed judgments of the court a quo.

In the petition before Us the petitioners have assigned the following errors:

I. The Court of Appeals erred in the finding that the

respondent is an industrial partner of Evangelista & Co.,

notwithstanding the admitted fact that since 1954 and until

after promulgation of the decision of the appellate court the

said respondent was one of the judges of the City Court of

Manila, and despite its findings that respondent had been paid

for services allegedly contributed by her to the partnership. In

this connection the Court of Appeals erred:

(A) In finding that the "amended Articles of Copartnership," Exhibit "A" is conclusive evidence

that respondent was in fact made an industrial

partner of Evangelista & Co.

(B) In not finding that a portion of respondent's

testimony quoted in the decision proves that said

respondent did not bind herself to contribute her

industry, and she could not, and in fact did not,

because she was one of the judges of the City

Court of Manila since 1954.

(C) In finding that respondent did not in fact

contribute her industry, despite the appellate

court's own finding that she has been paid for the

services allegedly rendered by her, as well as for

the loans of money made by her to the

partnership.

II. The lower court erred in not finding that in any event the

respondent was lawfully excluded from, and deprived of, her

alleged share, interests and participation, as an alleged

industrial partner, in the partnership Evangelista & Co., and its

profits or net income.

III. The Court of Appeals erred in affirming in toto the decision

of the trial court whereby respondent was declared an

industrial partner of the petitioner, and petitioners were

ordered to render an accounting of the business operation of

the partnership from June 7, 1955, and to pay the respondent

her alleged share in the net profits of the partnership plus the

sum of P2,000.00 as attorney's fees and the costs of the suit,

instead of dismissing respondent's complaint, with costs,

against the respondent.

It is quite obvious that the questions raised in the first assigned errors refer

to the facts as found by the Court of Appeals. The evidence presented by

the parties as the trial in support of their respective positions on the issue

of whether or not the respondent was an industrial partner was thoroughly

analyzed by the Court of Appeals on its decision, to the extent of

reproducing verbatim therein the lengthy testimony of the witnesses.

It is not the function of the Supreme Court to analyze or weigh such

evidence all over again, its jurisdiction being limited to reviewing errors of

law that might have been commited by the lower court. It should be

observed, in this regard, that the Court of Appeals did not hold that the

Articles of Co-partnership, identified in the record as Exhibit "A", was

conclusive evidence that the respondent was an industrial partner of the

said company, but considered it together with other factors, consisting of

both testimonial and documentary evidences, in arriving at the factual

conclusion expressed in the decision.

The findings of the Court of Appeals on the various points raised in the first

assignment of error are hereunder reproduced if only to demonstrate that

the same were made after a through analysis of then evidence, and hence

are beyond this Court's power of review.

The aforequoted findings of the lower Court are assailed

under Appellants' first assigned error, wherein it is pointed out

that "Appellee's documentary evidence does not conclusively

prove that appellee was in fact admitted by appellants as

industrial partner of Evangelista & Co." and that "The grounds

relied upon by the lower Court are untenable" (Pages 21 and

26, Appellant's Brief).

The first point refers to Exhibit A, B, C, K, K-1, J, N and S,

appellants' complaint being that "In finding that the appellee is

an industrial partner of appellant Evangelista & Co., herein

referred to as the partnership the lower court relied mainly

on the appellee's documentary evidence, entirely disregarding

facts and circumstances established by appellants" evidence

which contradict the said finding' (Page 21, Appellants' Brief).

The lower court could not have done otherwise but rely on the

exhibits just mentioned, first, because appellants have

admitted their genuineness and due execution, hence they

were admitted without objection by the lower court when

appellee rested her case and, secondly the said exhibits

indubitably show the appellee is an industrial partner of

appellant company. Appellants are virtually estopped from

attempting to detract from the probative force of the said

exhibits because they all bear the imprint of their knowledge

and consent, and there is no credible showing that they ever

protested against or opposed their contents prior of the filing

of their answer to appellee's complaint. As a matter of fact, all

the appellant Evangelista, Jr., would have us believe as

against the cumulative force of appellee's aforesaid

documentary evidence is the appellee's Exhibit "A", as

confirmed and corroborated by the other exhibits already

mentioned, does not express the true intent and agreement of

the parties thereto, the real understanding between them

being the appellee would be merely a profit sharer entitled to

30% of the net profits that may be realized between the

partners from June 7, 1955, until the mortgage loan of

P30,000.00 to be obtained from the RFC shall have been fully

paid. This version, however, is discredited not only by the

aforesaid documentary evidence brought forward by the

appellee, but also by the fact that from June 7, 1955 up to the

filing of their answer to the complaint on February 8, 1964

or a period of over eight (8) years appellants did nothing to

correct the alleged false agreement of the parties contained in

Exhibit "A". It is thus reasonable to suppose that, had appellee

not filed the present action, appellants would not have

advanced this obvious afterthought that Exhibit "A" does not

express the true intent and agreement of the parties thereto.

At pages 32-33 of appellants' brief, they also make much of

the argument that 'there is an overriding fact which proves that

the parties to the Amended Articles of Partnership, Exhibit "A",

did not contemplate to make the appellee Estrella Abad

Santos, an industrial partner of Evangelista & Co. It is an

admitted fact that since before the execution of the amended

articles of partnership, Exhibit "A", the appellee Estrella Abad

Santos has been, and up to the present time still is, one of the

judges of the City Court of Manila, devoting all her time to the

performance of the duties of her public office. This fact proves

beyond peradventure that it was never contemplated between

the parties, for she could not lawfully contribute her full time

and industry which is the obligation of an industrial partner

pursuant to Art. 1789 of the Civil Code.

The Court of Appeals then proceeded to consider appellee's testimony on

this point, quoting it in the decision, and then concluded as follows:

One cannot read appellee's testimony just quoted without

gaining the very definite impression that, even as she was and

still is a Judge of the City Court of Manila, she has rendered

services for appellants without which they would not have had

the wherewithal to operate the business for which appellant

company was organized. Article 1767 of the New Civil Code

which provides that "By contract of partnership two or more

persons bind themselves, to contribute money, property, or

industry to a common fund, with the intention of dividing the

profits among themselves, 'does not specify the kind of

industry that a partner may thus contribute, hence the said

services may legitimately be considered as appellee's

contribution to the common fund. Another article of the same

Code relied upon appellants reads:

'ART. 1789. An industrial partner cannot engage

in business for himself, unless the partnership

expressly permits him to do so; and if he should

do so, the capitalist partners may either exclude

him from the firm or avail themselves of the

benefits which he may have obtained in violation

of this provision, with a right to damages in either

case.'

It is not disputed that the provision against the industrial

partner engaging in business for himself seeks to prevent any

conflict of interest between the industrial partner and the

partnership, and to insure faithful compliance by said partner

with this prestation. There is no pretense, however, even on

the part of the appellee is engaged in any business

antagonistic to that of appellant company, since being a Judge

of one of the branches of the City Court of Manila can hardly

be characterized as a business. That appellee has faithfully

complied with her prestation with respect to appellants is

clearly shown by the fact that it was only after filing of the

complaint in this case and the answer thereto appellants

exercised their right of exclusion under the codal art just

mentioned by alleging in their Supplemental Answer dated

June 29, 1964 or after around nine (9) years from June 7,

1955 subsequent to the filing of defendants' answer to the

complaint, defendants reached an agreement whereby the

herein plaintiff been excluded from, and deprived of, her

alleged share, interests or participation, as an alleged

industrial partner, in the defendant partnership and/or in its net

profits or income, on the ground plaintiff has never contributed

her industry to the partnership, instead she has been and still

is a judge of the City Court (formerly Municipal Court) of the

City of Manila, devoting her time to performance of her duties

as such judge and enjoying the privilege and emoluments

appertaining to the said office, aside from teaching in law

school in Manila, without the express consent of the herein

defendants' (Record On Appeal, pp. 24-25). Having always

knows as a appellee as a City judge even before she joined

appellant company on June 7, 1955 as an industrial partner,

why did it take appellants many yearn before excluding her

from said company as aforequoted allegations? And how can

they reconcile such exclusive with their main theory that

appellee has never been such a partner because "The real

agreement evidenced by Exhibit "A" was to grant the appellee

a share of 30% of the net profits which the appellant

partnership may realize from June 7, 1955, until the mortgage

of P30,000.00 obtained from the Rehabilitation Finance

Corporal shall have been fully paid." (Appellants Brief, p. 38).

What has gone before persuades us to hold with the lower

Court that appellee is an industrial partner of appellant

company, with the right to demand for a formal accounting and

to receive her share in the net profit that may result from such

an accounting, which right appellants take exception under

their second assigned error. Our said holding is based on the

following article of the New Civil Code:

'ART. 1899. Any partner shall have the right to a

formal account as to partnership affairs:

(1) If he is wrongfully excluded from the partnership business

or possession of its property by his co-partners;

(2) If the right exists under the terms of any agreement;

(3) As provided by article 1807;

(4) Whenever

reasonable.

other

circumstance

render

it

just

and

We find no reason in this case to depart from the rule which limits this

Court's appellate jurisdiction to reviewing only errors of law, accepting as

conclusive the factual findings of the lower court upon its own assessment

of the evidence.

The judgment appealed from is affirmed, with costs.

Zaldivar, Castro, Fernando, Teehankee, Barredo, Makasiar, Antonio and

Esguerra, JJ., concur.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Imported Website 5 - AnnotatedDocument7 pagesImported Website 5 - AnnotatedAudrey DeguzmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Partnership Batch 2Document18 pagesPartnership Batch 2Rock StonePas encore d'évaluation

- Partnership CasesDocument30 pagesPartnership CasescandicePas encore d'évaluation

- Supreme Court: Leonardo Abola For Petitioners. Baisas, Alberto & Associates For RespondentDocument5 pagesSupreme Court: Leonardo Abola For Petitioners. Baisas, Alberto & Associates For RespondentAyenGailePas encore d'évaluation

- Evangelista and Co Vs Abad Santos G.R. No. L-31684Document5 pagesEvangelista and Co Vs Abad Santos G.R. No. L-31684crizaldedPas encore d'évaluation

- Evangelista & Co. vs. Abad Santos: 416 Supreme Court Reports AnnotatedDocument6 pagesEvangelista & Co. vs. Abad Santos: 416 Supreme Court Reports AnnotatedIrish Joi TapalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Evangelista Vs SantosDocument5 pagesEvangelista Vs SantosReth GuevarraPas encore d'évaluation

- PARTNERSHIP Syllabus Cases FulltextDocument174 pagesPARTNERSHIP Syllabus Cases FulltextJacobPas encore d'évaluation

- Evangelista v. Abad SantosDocument7 pagesEvangelista v. Abad SantosLorjyll Shyne Luberanes TomarongPas encore d'évaluation

- Evangelista & Co. v. SantosDocument5 pagesEvangelista & Co. v. SantosClement del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Petitioners vs. vs. Respondent Leonardo Abola Baizas, Alberto & AssociatesDocument5 pagesPetitioners vs. vs. Respondent Leonardo Abola Baizas, Alberto & AssociatesRobyn BangsilPas encore d'évaluation

- Petitioners vs. vs. Respondent Leonardo Abola Baizas, Alberto & AssociatesDocument5 pagesPetitioners vs. vs. Respondent Leonardo Abola Baizas, Alberto & AssociatesAyana Dela CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- Petitioners vs. vs. Respondent Leonardo Abola Baizas, Alberto & AssociatesDocument5 pagesPetitioners vs. vs. Respondent Leonardo Abola Baizas, Alberto & AssociatesRobyn BangsilPas encore d'évaluation

- Supreme Court: Leonardo Abola For Petitioners. Baisas, Alberto & Associates For RespondentDocument70 pagesSupreme Court: Leonardo Abola For Petitioners. Baisas, Alberto & Associates For RespondentAbegail Olario AdajarPas encore d'évaluation

- Evangelista v. Abad SantosDocument8 pagesEvangelista v. Abad SantosMarinella ReyesPas encore d'évaluation

- Partnership Full Text IIDocument39 pagesPartnership Full Text IIMJ CemsPas encore d'évaluation

- Cases Article 1786-1809Document17 pagesCases Article 1786-1809luckyPas encore d'évaluation

- 1789 - Evangelista vs. Abad-Santos, 51 SCRA 416 - DIGESTDocument2 pages1789 - Evangelista vs. Abad-Santos, 51 SCRA 416 - DIGESTI took her to my penthouse and i freaked itPas encore d'évaluation

- Evangelista v. Abad Santos - DigestDocument4 pagesEvangelista v. Abad Santos - DigestJaysieMicabaloPas encore d'évaluation

- EVANGELISTA & Co. VS Abad Santos DigestedDocument2 pagesEVANGELISTA & Co. VS Abad Santos Digestedgregoriomanueldon.patrocinioPas encore d'évaluation

- Evangelista v. SantosDocument3 pagesEvangelista v. Santosmichelle zatarainPas encore d'évaluation

- Evangelista Vs Abad SantosDocument2 pagesEvangelista Vs Abad SantosNic NalpenPas encore d'évaluation

- 51-ATP-Evangelista v. SantosDocument2 pages51-ATP-Evangelista v. SantosJoesil Dianne SempronPas encore d'évaluation

- Evangelista and Co vs. Estrella Abad Santos FactsDocument15 pagesEvangelista and Co vs. Estrella Abad Santos FactsKing BadongPas encore d'évaluation

- Sison Vs McQuiad, G.R. No. L-6304 December 29, 1953Document2 pagesSison Vs McQuiad, G.R. No. L-6304 December 29, 1953Dianne BalagsoPas encore d'évaluation

- Evangelista Vs Abad SantosDocument2 pagesEvangelista Vs Abad SantosMaribel Nicole LopezPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 8Document5 pages5 8Michaela Anne CapiliPas encore d'évaluation

- FELICIANO, Ludy Jane P. G.R. No. 70926 January 31, 1989 DAN FUE LEUNG, Petitioner, Hon. Intermediate Appellate Court and Leung Yiu, RespondentsDocument3 pagesFELICIANO, Ludy Jane P. G.R. No. 70926 January 31, 1989 DAN FUE LEUNG, Petitioner, Hon. Intermediate Appellate Court and Leung Yiu, RespondentsGio Soriano BengaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Jarantilla, Jr. vs. Jarantilla 636 SCRA 299, G.R. No. 154486, December 1, 2010, Leonardo-De Castro, J.Document12 pagesJarantilla, Jr. vs. Jarantilla 636 SCRA 299, G.R. No. 154486, December 1, 2010, Leonardo-De Castro, J.Bea AlduezaPas encore d'évaluation

- Partnership Digest 12Document6 pagesPartnership Digest 12John Henry CasugaPas encore d'évaluation

- VICTORINA ALICE LIM LAZARO v. BREWMASTER INTERNATIONALDocument7 pagesVICTORINA ALICE LIM LAZARO v. BREWMASTER INTERNATIONALKhate AlonzoPas encore d'évaluation

- Tai Tong Chuache & Co. V. The Insurance Commission and Travellers Multi-IndemnityDocument8 pagesTai Tong Chuache & Co. V. The Insurance Commission and Travellers Multi-IndemnityRodeleine Grace C. MarinasPas encore d'évaluation

- Case 5Document3 pagesCase 5April CaringalPas encore d'évaluation

- Evangelista and Co. Vs Estrella Abad Santos, G.R. No. L.31684, July 28, 1973-DIGESTEDDocument2 pagesEvangelista and Co. Vs Estrella Abad Santos, G.R. No. L.31684, July 28, 1973-DIGESTEDRaymer OclaritPas encore d'évaluation

- 7.litonjua, Jr. vs. Litonjua, Sr.Document24 pages7.litonjua, Jr. vs. Litonjua, Sr.KKCDIALPas encore d'évaluation

- 11 Evangelista & Co., Et Al. V Abad Santos, GR NO. L-31684, June 28. 1973 PDFDocument6 pages11 Evangelista & Co., Et Al. V Abad Santos, GR NO. L-31684, June 28. 1973 PDFMark Emmanuel LazatinPas encore d'évaluation

- Agad-Mabato DigestDocument60 pagesAgad-Mabato DigestReuben EscarlanPas encore d'évaluation

- Jarantilla JR Vs Jarantilla DigestsDocument5 pagesJarantilla JR Vs Jarantilla DigestsAida Tadal GalamayPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Digests - Biz Org-6,12,18Document4 pagesCase Digests - Biz Org-6,12,18Louiegie Thomas San JuanPas encore d'évaluation

- 2nd Exam Case DigestDocument31 pages2nd Exam Case DigestbubblingbrookPas encore d'évaluation

- Idos vs. CADocument3 pagesIdos vs. CAGia DimayugaPas encore d'évaluation

- Feu Leung Vs Intermediate Appellate CourtDocument3 pagesFeu Leung Vs Intermediate Appellate CourtAiza MercaderPas encore d'évaluation

- Moran, Jr. v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 59956Document10 pagesMoran, Jr. v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 59956Krister VallentePas encore d'évaluation

- Case Digests 1Document18 pagesCase Digests 1Yoan Baclig BuenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Dan Fue Leung v. Intermediate Appellate CourtDocument10 pagesDan Fue Leung v. Intermediate Appellate CourtSecret SecretPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Digest 2Document38 pagesCase Digest 2Clarise Satentes Aquino100% (1)

- Leung vs. Iac GR No. 709826, Jan. 31, 1989Document7 pagesLeung vs. Iac GR No. 709826, Jan. 31, 1989FranzMordenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Sison v. McQuaidDocument2 pagesSison v. McQuaidSecret SecretPas encore d'évaluation

- Mod3 - 2 - G.R. No. 154486 Jarntilla V Jarantilla - DigestDocument3 pagesMod3 - 2 - G.R. No. 154486 Jarntilla V Jarantilla - DigestOjie Santillan100% (2)

- Evangelista vs. Abad SantosDocument2 pagesEvangelista vs. Abad Santosmitsudayo_Pas encore d'évaluation

- Briones Vs Cammayo 41 SCRA 404Document14 pagesBriones Vs Cammayo 41 SCRA 404Kimberly Anne LatonioPas encore d'évaluation

- Partnership Dec 17 - DigestDocument55 pagesPartnership Dec 17 - DigestJo LazanasPas encore d'évaluation

- Agency CasesDocument25 pagesAgency CasesJan Aldrin AfosPas encore d'évaluation

- 42-ATP-Sunga-Chan v. Lamberto ChuaDocument2 pages42-ATP-Sunga-Chan v. Lamberto ChuaJoesil Dianne SempronPas encore d'évaluation

- 8barons Marketing v. CA 286 SCRA 96 GR 126486 02091998 G.R. No. 126486Document7 pages8barons Marketing v. CA 286 SCRA 96 GR 126486 02091998 G.R. No. 126486sensya na pogi langPas encore d'évaluation

- 8barons Marketing v. CA 286 SCRA 96 GR 126486 02091998 G.R. No. 126486Document7 pages8barons Marketing v. CA 286 SCRA 96 GR 126486 02091998 G.R. No. 126486sensya na pogi langPas encore d'évaluation

- Pideli To LittonDocument39 pagesPideli To LittonHao Wei WeiPas encore d'évaluation

- Arnold v. Willets and Patterson, LTD., 44 Phil. 634 (1923)Document10 pagesArnold v. Willets and Patterson, LTD., 44 Phil. 634 (1923)inno KalPas encore d'évaluation

- Drafting Written Statements: An Essential Guide under Indian LawD'EverandDrafting Written Statements: An Essential Guide under Indian LawPas encore d'évaluation

- Motions, Affidavits, Answers, and Commercial Liens - The Book of Effective Sample DocumentsD'EverandMotions, Affidavits, Answers, and Commercial Liens - The Book of Effective Sample DocumentsÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (14)

- UN Messenger of Peace L.dcaprio 22 April 2016Document4 pagesUN Messenger of Peace L.dcaprio 22 April 2016agnatgaPas encore d'évaluation

- Special Civil LawsDocument38 pagesSpecial Civil LawsagnatgaPas encore d'évaluation

- NCC Codal ProvisionsDocument1 pageNCC Codal ProvisionsagnatgaPas encore d'évaluation

- Tables of LegitimesDocument2 pagesTables of LegitimesagnatgaPas encore d'évaluation

- D8 LAW FIRM OF LAGUESMA Vs COA PDFDocument13 pagesD8 LAW FIRM OF LAGUESMA Vs COA PDFagnatgaPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Volcanos - Archl InfluencesDocument6 pages5 Volcanos - Archl InfluencesagnatgaPas encore d'évaluation

- CrimLawRev Case Digest (Batch 1) PDFDocument69 pagesCrimLawRev Case Digest (Batch 1) PDFagnatgaPas encore d'évaluation

- 1.21 Magalona Vs PesaycoDocument4 pages1.21 Magalona Vs PesaycoagnatgaPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Digest Corpo Dean Divina Batch 1Document12 pagesCase Digest Corpo Dean Divina Batch 1agnatgaPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Digest Corpo Batch 2Document1 pageCase Digest Corpo Batch 2agnatgaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2014 Article 115 PDFDocument10 pages2014 Article 115 PDFagnatgaPas encore d'évaluation

- Puentebella v. Negros CoalDocument11 pagesPuentebella v. Negros CoalagnatgaPas encore d'évaluation

- Korea Techologies v. LermaDocument34 pagesKorea Techologies v. LermaagnatgaPas encore d'évaluation

- Michalis+Tsitsekkos+&+Associates+LLC BrochureDocument25 pagesMichalis+Tsitsekkos+&+Associates+LLC BrochureIrinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Discussions On Chapter 4Document7 pagesDiscussions On Chapter 4Norren Thea VlogsPas encore d'évaluation

- Mid-Sem Exam NotesDocument21 pagesMid-Sem Exam Notesdaksh.aggarwal26Pas encore d'évaluation

- Partnership Agreement: State of - Rev. 133A254Document5 pagesPartnership Agreement: State of - Rev. 133A254Jayhan PalmonesPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Business PlanDocument33 pagesFinal Business PlanGoabaone KokolePas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Corporation Accounting IntroductionDocument6 pages1 Corporation Accounting IntroductionShane Ivory ClaudioPas encore d'évaluation

- Module Three Forms of Legal Business OwnershipDocument68 pagesModule Three Forms of Legal Business OwnershipsifakiwovelePas encore d'évaluation

- BDPW3103 Introductory Finance - Vapr20Document196 pagesBDPW3103 Introductory Finance - Vapr20Sobanah Chandran100% (2)

- Paper5 2Document61 pagesPaper5 2RAj BardHanPas encore d'évaluation

- Rodel M. Sescon, MM: InstructorDocument23 pagesRodel M. Sescon, MM: InstructorR.v.EscoroPas encore d'évaluation

- Capital V RevenueDocument18 pagesCapital V RevenueFaizan FaruqiPas encore d'évaluation

- Obligations Case DigestsDocument28 pagesObligations Case DigestsJun-Jun del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- LL.B. (Hons) 3 YEARDocument88 pagesLL.B. (Hons) 3 YEARAmar KapoorPas encore d'évaluation

- The Private Equity CookbookDocument164 pagesThe Private Equity CookbookJim MacaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Highlights of The Revised Corporation CodeDocument22 pagesHighlights of The Revised Corporation CodeLuigi JaroPas encore d'évaluation

- Afar Study Plan: May 2019 Exam RecapDocument4 pagesAfar Study Plan: May 2019 Exam RecapLoise Anne MadridPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Become Member of CciDocument20 pagesHow To Become Member of CcisalmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Contract Law Mansi: General MetricsDocument20 pagesContract Law Mansi: General Metricsgolu tripathiPas encore d'évaluation

- Lambers BEC TextDocument384 pagesLambers BEC Textalik711698100% (2)

- Article 1767Document2 pagesArticle 1767Noreen67% (9)

- 02 Admission of PartnerDocument21 pages02 Admission of PartnerSaurya RaiPas encore d'évaluation

- A Partnership Is Defined in SectionDocument9 pagesA Partnership Is Defined in Sectionaripmira93Pas encore d'évaluation

- MCQsDocument48 pagesMCQsSujeetDhakalPas encore d'évaluation

- Syllabus Spec Pro StudentsDocument9 pagesSyllabus Spec Pro StudentsMa. Ana Joaquina SahagunPas encore d'évaluation

- 815 Model Answer Summer 2017 PDFDocument28 pages815 Model Answer Summer 2017 PDFBqunahPas encore d'évaluation

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: Business 9609/12 March 2020Document17 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: Business 9609/12 March 2020Ayush OjhaPas encore d'évaluation

- Al Accounting 2020-VfDocument22 pagesAl Accounting 2020-VfIdrak & Idris FaroukPas encore d'évaluation

- Limited Liability Partnership in India: Study of Different Aspects For Optimum GrowthDocument6 pagesLimited Liability Partnership in India: Study of Different Aspects For Optimum GrowthUjjawal Agrawal100% (1)

- Venture Capital - Fund Raising and Fund StructureDocument52 pagesVenture Capital - Fund Raising and Fund StructureSimon ChenPas encore d'évaluation

- How Company Distinguish From PartnershipDocument2 pagesHow Company Distinguish From PartnershipIshan AggarwalPas encore d'évaluation