Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Meadowcroft & Ruger "Hayek, Friedman, and Buchanan: On Public Life, Chile, and The Relationship Between Liberty and Democracy" (2014)

Transféré par

Liga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Meadowcroft & Ruger "Hayek, Friedman, and Buchanan: On Public Life, Chile, and The Relationship Between Liberty and Democracy" (2014)

Transféré par

Liga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

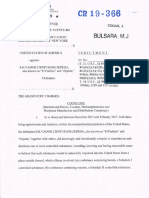

This article was downloaded by: [University of York]

On: 18 August 2014, At: 08:20

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered

office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Review of Political Economy

Publication details, including instructions for authors and

subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/crpe20

Hayek, Friedman, and Buchanan: On

Public Life, Chile, and the Relationship

between Liberty and Democracy

a

John Meadowcroft & William Ruger

a

King's College London, London, UK

Texas State University, San Marcos, USA

Published online: 11 Jul 2014.

To cite this article: John Meadowcroft & William Ruger (2014) Hayek, Friedman, and Buchanan:

On Public Life, Chile, and the Relationship between Liberty and Democracy, Review of Political

Economy, 26:3, 358-367, DOI: 10.1080/09538259.2014.932066

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09538259.2014.932066

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the

Content) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,

our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to

the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions

and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,

and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content

should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources

of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,

proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or

howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising

out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any

substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,

systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &

Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/termsand-conditions

Review of Political Economy, 2014

Vol. 26, No. 3, 358 367, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09538259.2014.932066

Hayek, Friedman, and Buchanan: On

Public Life, Chile, and the Relationship

between Liberty and Democracy

JOHN MEADOWCROFT & WILLIAM RUGER

Downloaded by [University of York] at 08:20 18 August 2014

Kings College London, London, UK;

USA

Texas State University, San Marcos,

(Received 14 September 2013; accepted 20 November 2013)

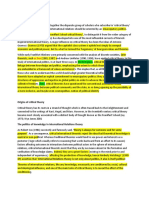

ABSTRACT This article places recent evidence of Hayeks public defense of the Pinochet

regime in the context of the work of the other great twentieth-century classical liberal

economists, Milton Friedman and James M. Buchanan. Hayeks view that liberty was

only instrumentally valuable is contrasted with Buchanans account of liberty situated

in the notion of the inviolable individual. It is argued that Hayeks theory left him with

no basis on which to demarcate the legitimate actions of the state, so that conceivably

any government action could be justified on consequentialist grounds. Furthermore,

Friedmans account of freedom and discretionary power undermines Hayeks proposal

that a transitional dictatorship could pave the way for a genuinely free society. It is

contended that Hayeks defense of Pinochet follows from pathologies of his theories of

liberty and democracy.

1. Introduction

There have long been rumors and counter-rumors about F.A. Hayeks alleged

support for the Pinochet regime. Farrant & McPhails article in this issue shows

that at best Hayek was in a state of denial about the regime and at worse was prepared to justify horrific human rights abuses in the cause of anti-Communism and

economic liberalization. No one can read the Report of the Chilean National Commission on Truth and Reconciliation (1993), which details the thousands of arbitrary arrests, summary executions, and imprisonments without due process that

took place under the Pinochet regime, and be impressed with Hayeks claim

that I have not been able to find a single person even in much maligned Chile

Correspondence Address: John Meadowcroft, Kings College London, Department of Political

Economy, Strand Building, Strand Campus, London WC2R 2LS, UK, E-mail: john.meadowcroft@

kcl.ac.uk

# 2014 Taylor & Francis

Downloaded by [University of York] at 08:20 18 August 2014

Hayek, Friedman, and Buchanan

359

who did not agree that personal freedom was greater under Pinochet than it had

been under Allende (Farrant & McPhail, 2014).

As Farrant & McPhail show, Hayek was at best ambivalent in his criticism of

a number of authoritarian regimes, including the Salazar regime in Portugal, the

military dictatorship in Argentina and Pinochets government in Chile. Farrant

& McPhail argue that Hayek subscribed to a notion of transitional dictatorshipthe view that an authoritarian regime could facilitate a transition to a

liberal order more effectively than a democratic government. It appears to have

been on this basis that Hayek was willing to turn a blind eye to human rights

abuses if those abuses were committed in order to facilitate a long-term transition

to a more liberal order.

This paper will consider Hayeks actions as a public intellectual with those of

the other two of the big three of twentieth century classical liberal economists:

Milton Friedman and James M. Buchanan. First, we briefly discuss how each

viewed political engagement and we talk about Hayeks ideas about liberty and

transitional dictatorships, with special attention to Buchanans contrary view of

liberty and how it serves to ground a critique of Hayek. Then we examine Friedmans own association with Pinochet and how his views on freedom and discretion relate to Hayeks understanding of transitional dictatorship. We conclude

by reflecting on Hayeks support for transitional dictatorships and for Pinochet

in particular.

2. Hayeks Ideas and the Relevance of the Pinochet Revelations

Hayek and Friedman are two notable examples of economists who used their scholarly status as a springboard into public life. Both were active writing books and

lecturing for general audiences, appearing in newspapers and on the radio and television, and advising political actors at home and abroad. Given that they shared

classical liberal views at odds with the reigning orthodoxy of their time, it is unsurprising that their engagement with the political world was controversial. It can be

argued that much of the influence that Friedman and Hayek exerted upon the

world of policy and politics can be attributed to their engagement with public discourse and their efforts in institution building for the cause of classical liberalism.

Not all distinguished scholars choose to avail themselves of such opportunities. James M. Buchanan largely eschewed the public sphere as a matter of principle even at the cost of political influence (Buchanan, 2007, p. 97). There are

nevertheless dangers for any scholar who chooses to align himself with political

figures, partisan or bureaucratic. Most significant is the danger of guilt by association. By definition, practical politicians introduce policies across a range of

domains, and although a scholar may agree with the main thrust of policy, there

will always be specific issues where disagreement exists, although such nuances

may be lost in the popular imagination.

It can be argued that the dalliances of scholars with particular politicians are

the unfortunate but ephemeral business of day-to-day politics that will, or should,

be ultimately forgotten, while a scholars contribution to the realm of ideas will

endure. Farrant & McPhail (2014) argue, however, that Hayeks support for Pinochet is a direct result of Hayeks belief in the capacity of transitional dictatorship

Downloaded by [University of York] at 08:20 18 August 2014

360 J. Meadowcroft & W. Ruger

to facilitate a shift to a more liberal order and that his position vis-a`-vis Pinochet

therefore constitutes an indictment of key aspects of Hayeks intellectual contribution.

We agree that Hayeks defense of Pinochet has important implications for

our understanding and assessment of his whole intellectual contribution, but we

argue that the implications for Hayeks social and political theory may be more

serious than Farrant & McPhail claim as they go to the core of his views about

libertya crucial aspect of the thought of any liberal scholar.

Hayeks enterprise can be understood as an attempt to synthesis the Kantian

and Humean traditions of liberal thought; traditions that emphasize, respectively,

the importance of individual reason and rational construction and of evolutionary

processes without conscious control in the development of modern liberal

societies. Hayeks unique intellectual contribution stems from the bold, although

surely unsuccessful, attempt to bring together the Kantian and Humean (Kukathas,

1989).

The tensions between Kantian deontological positions and Humean consequentialist arguments are particularly apparent in Hayeks case for liberty.

Hayek (1960, p. 12) sets out a purely negative conception of liberty, arguing, in

Kantian terms, that freedom describes the absence of coercion, so that the only

infringement of it is coercion by men and the range of physical possibilities

from which a person can choose at a given moment has no direct relevance to

freedom.

While Hayek defines liberty in Kantian terms, his account of the value of

liberty is Humean. Hayek argues that freedom does not have intrinsic value but

is instrumentally valuable because it is necessary to secure the collective benefits

of social and economic progress: What is important is not what freedom I personally would like to exercise but what freedom some person may need in order to do

things beneficial to society (Hayek, 1960, p. 32). For Hayek (1960, p. 29), the

case for individual freedom does not rest upon a deontological account of the

dignity of the individual, but rather follows from an appreciation of the incompatibility of socialist central planning and a complex, advanced society. People must

be free to use their own personal knowledge in order that an advanced market

order can exist; so the case for liberty rests chiefly on the recognition of the inevitable ignorance of all of us concerning a great many of the factors on which the

achievement of our ends and welfare depends (Hayek, 1960, p. 29).

It is significant that, for Hayek, should our fundamental ignorance of how to

plan a complex, advanced economy miraculously disappear, the case for liberty

would also evaporate: If there were omniscient men, if we could know not

only all that affects the attainment of our present wishes but also our future

wants and desires, there would be little case for liberty (Hayek, 1960, p. 29).

Given the nature of the allegations surrounding Hayeks support for Pinochet

this statement is particularly unfortunate.

It is unsurprising that for Hayek democracy similarly has only instrumental

value. Hayek (1960, p. 106) wrote: However strong the general case for democracy, it is not an ultimate or absolute value and must be judged by what it will

achieve. It is probably the best method for achieving certain ends, but not an

end in itself. For Hayek, democracy was important as a peaceful means of

Downloaded by [University of York] at 08:20 18 August 2014

Hayek, Friedman, and Buchanan

361

removing an unpopular or ineffective government, but no special value should be

attributed to a decision because it happened to reflect the will of a numerical

majority of the voting population.

Concerns about the threat of majoritarian tyranny implicit in democratic

decision-making occupy a place within mainstream liberal thought. But when

those concerns are coupled with Hayeks rejection of the idea that liberty has

intrinsic value, we seem to be left in the altogether uncomfortable position that

individual freedom is only to be enforced and individuals are only to be

allowed to participate in collective decision-making if it can be demonstrated

that socially beneficial outcomes follow. But Hayek does not specify who will

make such judgments or what criteria will be used to evaluate social benefit

other than to imply that he is able to make such judgments against criteria he

has devised.

As Farrant & McPhail (2014) note, Hayek viewed the Allende government as

an example of the excesses of majoritarian democracy. Allende had been elected

on a broad, popular program, but he thenillegitimately, in the view of some

observersintroduced radical socialist policies, including the nationalization of

the financial and productive sectors of the economy, the expropriation of large

swathes of rural property and the introduction of extensive price controls

(Valdes, 1995, pp. 6 7). Given Hayeks views about the purely instrumental

value of democracy and the most efficacious economic policy, it is hardly surprising that he was sympathetic to Pinochets actions in overthrowing the Allende

regime and setting Chile on a new economic course.

However, while the Pinochet regime did introduce economic reforms that

correlated with an impressive period of economic growth, the regime also

embarked upon a system of institutionalized terror designed to destroy opposition in the traditional parties of the left, trade unions and elsewhere. As a consequence, more than 2,000 people disappeared, many more people were

summarily arrested and tortured, and hundreds of thousands of Chileans were

exiled, so that all formal opposition to the regime was driven underground

(Chilean National Commission on Truth and Reconciliation, 1993; Valdes,

1995, p. 30). The evidence presented by Farrant & McPhail makes clear that

Hayek knew of these abuses but was nevertheless willing to give public

support to the Pinochet regime. Hayeks statements on this matter expose a fundamental weakness of his thought that follows from his failure to ascribe intrinsic

value to liberty and to utilize a conception of universal and inalienable individual

rights.

Hayeks belief that liberty is only instrumentally valuable is consistent with

the fact that he generally eschewed the language of rights (Kukathas, 1989,

p. 144). He did, however, on occasion invoke the concept of rights in describing

the role of government in the protection of individual liberty. In The Mirage of

Social Justice, for example, Hayek (1976, p. 101) wrote that where men have

formed organizations such as government for enforcing rules of conduct, the individual will have a claim in justice on government that his right be protected and

infringements made good. But Hayek stressed that such rights were not universal

or absolute, but were simply obligations that arose on occasions between particular persons or organizations.

Downloaded by [University of York] at 08:20 18 August 2014

362 J. Meadowcroft & W. Ruger

While Hayeks principal concern in this context was to critique the notion of

social rights, it is nevertheless apparent that for Hayek there were no natural,

inalienable or universal rights. Although Hayek saw rights as a useful term to

describe the individual liberty he considered instrumentally important for the

maintenance of a prosperous society, he did not see rights as describing a particular category of universal or absolute protections ascribed to all individuals as individuals.

James M. Buchanan likewise did not subscribe to an account of natural rights.

Buchanan similarly saw rights as emerging from political agreement, but for

Buchanan this was because individuals were the ultimate source of value, so

rights could not exist independently of the values of individual men and

women. Rights were created when people chose to respect the persons and property of others. For Buchanan, rights were agreed as part of the process by which

people left the state of nature and entered into the social contract. Rights come into

existence when some general agreement to respect the rights of others is formalized into law (Buchanan, 1974).

Buchanan took a methodological and ethical individualist approach based

upon the Kantian precept that individuals must be treated as ends and never as

means. No individual has any more or less moral worth than any other person

and therefore no individual may be sacrificed for the benefit of others. For Buchanan (1977, p. 244), individual human beings are the ultimate ethical units. . . .

[P]ersons are to be treated strictly as ends and never as means, and that there

are no transcendental, suprapersonal norms. Accordingly, Individual freedom

is important, not as an instrumental element in attaining economic or cultural

bliss, and not as some metaphysically superior value, but because it must

follow from the adoption of methodological and ethical individualism (Buchanan,

1974, pp. 5 6). For Buchanan, individuals are the ultimate source of value and

nothing could be done to individuals without their consent, unless, of course,

they had transgressed the rights of others, in which case punishment that had

been unanimously pre-agreed should follow. For Buchanan, each individual was

a veto-player vis-a`-vis the legitimate actions of the state (Buchanan, 1974; Meadowcroft, 2011, Chapter 2).

Hayeks social and political theory did not rule out the abuses of the Pinochet

regime, given that he viewed individual liberty as only instrumentally valuable,

and he would have considered the overarching economic goals of the regime

socially beneficial. Buchanans constitutional political economy, by contrast,

did preclude the actions of the Pinochet government (and indeed those of the

Allende government in going beyond its electoral mandate) given that we can

assume that the victims of the regime would not have consented to their abuse.

Thus, Hayeks support for Pinochet is indicative of a fundamental weakness of

his scholarly position that is not present in Buchanans work.

3. Friedman and Pinochet: Freedom and Discretion

Given Buchanans principled aloofness from politics, he was untouched by controversy over Pinochet. Friedman, though, was not able to avoid such controversy

due to his well-known connection, direct and indirect, with Pinochets Chile. This

Downloaded by [University of York] at 08:20 18 August 2014

Hayek, Friedman, and Buchanan

363

controversy followed him throughout his career (and beyond; see Klein, 2007).

Yet Friedmans stated views about Chile and his more general ideas about

liberty and political-economic arrangements provide a critique of Hayeks more

accepting stance towards dictatorships.

In terms of indirect connections, Friedmans free-market approachand

especially his scholarly work on monetary policywas a major intellectual influence on Pinochets economic team (the Chicago Boys) and its infamous economic reform plan for Chile (outlined in a 1970 document known as el ladrillo

or the brick). For some of these policymakers, the connection with Friedman

occurred in the classroom. Under the auspices of a pre-Pinochet USAID-financed

relationship between the University of Chicago and the Catholic University of

Chile, a stream of Chilean students studied economics at Chicago from 1955 to

1964. Some of these students were later involved with the Pinochet regime

although importantly they were not key figures until after the failure of the

regimes initial attempts to manage the economy. As Deirdre McCloskey

(2003) has pointed out, Friedmans colleagues Al Harberger, Larry Sjaastad,

and Greg Lewisnot Friedman himselfwere the key connections to Chile

and these students.

But Friedman had a more direct connection with Chile than his academic

work. He visited Chile on two occasions during Pinochets rule. The most important visit was a six-day trip in March 1975 arranged by Harberger. During those six

days, Friedman participated in seminars (planned for government officials, representatives of the public, and members of the military) and gave public lectures

(Friedman & Friedman, 1998, p. 399). Most importantly, Friedman was a

member of a small group that met with Pinochet for approximately 45 minutes.

During that short meeting, Friedman and the others discussed using shock treatment to deal with Chiles economic woes (Friedman & Friedman, 1998, p. 399).

At Pinochets request, Friedman produced a brief report of the Chilean situation

that he sent as a letter to the General on April 21, 1975. Ruger (2011,

pp. 54 55) summarizes it as follows:

Friedman unsurprisingly told the president to adopt a package of free-market

and monetarist reforms. In particular, Friedman argued that Chiles inflation

problems were so severe that shock treatment was necessary, despite his

typical preference for gradualism. Such treatment would include drastically

cutting the rate of increase in the money supply, cutting the fiscal deficit by substantially reducing government spending, and publicly committing to abjure

printing money to finance future government spending. He also advocated

that the government promote a social market economy by removing barriers

(such as wage and price controls) to the effective working of market forces

and freeing international trade. In short, Friedman counseled that No obstacles,

no subsidies should be the rule. Showing he was not unsympathetic to the hardships this would cause, nor unappreciative of the politics of reform, Friedman

also argued that the government should provide for the relief of any cases of

real hardship and severe distress among the poorest classes.

Friedman later claimed that he never advised Pinochet (for example, see Friedman, 1991b). However, both the meeting and the report sound like advice

though it is certainly true that he was never an advisor with any official post or

Downloaded by [University of York] at 08:20 18 August 2014

364 J. Meadowcroft & W. Ruger

in unofficial regular contact with the regime. Friedman himself admitted that the

meeting with Pinochet gave an iota of substance to later charges that I was a personal adviser to the general (Friedman & Friedman, 1998, p. 399). However, it is

worth noting that Pinochet himself told Friedman that the reports substance

coincided with the plan that had already been adopted and was then being

implemented (Pinochet, 1975, p. 594). Hence, Friedmans advice had little independent influence.

Before controversy erupted over Friedmans visit to Chile there was also evidence that he was no fan of Pinochets dictatorship. As Harberger (1976, p. 598)

notes, Friedman declined two offers of honorary degrees from Chilean universities,

precisely because he felt that acceptance of such honors from universities receiving

government funds could be interpreted as implying political approval. Friedman

also gave an anti-totalitarian lecture in Chile titled The Fragility of Freedom

in which he argued that centralization destroys freedom, free markets are essential

to maintaining freedom, and political freedom allowed markets to function best (see

Friedman, 2000). Later, in the midst of the controversy, Friedman noted that if he

had been a Chilean, he would, if possible have opposed both [Allende and

Pinochet]or alternatively have emigrated, and that he would fervently wish

their replacement by free democratic societies (Friedman, 1975b, pp. 595596).

Indeed, he called both options for Chile two evils. Years later, Friedman was

quite blunt about Pinochets non-economic record. In 1991, Friedman sharply

noted I have nothing good to say about the political regime that Pinochet

imposed. It was a terrible political regime (Friedman, 1991a). That same year,

he exclaimed in another speech: I never supported Pinochet (Friedman, 1991b).

These statements, particularly the claim that he would have opposed the

regime or emigrated, indicate that Friedman was no advocate of Hayeks

second-best solution of a transitional dictatorship. Despite categorizing the Pinochet regime as evil, Friedman nevertheless did say that with a military junta, there

is more chance of a return to a democratic society (Friedman, 1975b, p. 595). And

later he trumpeted that this is exactly what did happen, along with an economic

miracle. Yet we have seen no evidence that Friedman thought the ends justified

the means, despite later speaking highly of Chiles ultimate economic success and

proudly accepting a share of the credit for the economic job the Chicago Boys performed (Friedman, 1982, 1991b; Friedman & Friedman, 1998, pp. 405 408).

In terms of his rationale for engaging morally dubious regimes on the socalled left (China, Yugoslavia) or right (Chile, Iran), Friedman relied upon a consequentialist decision rule. He thought it was acceptable to visit, lecture, and give

advice on economic policy to political regimes you disapprove when doing so

would break down barriers between countries (Friedman, 1977, p. 600). Moreover, he saw himself akin to a physician giving technical advice to a government

so it could better ameliorate bad outcomes for society (Friedman, 1976, p. 596).

Most specifically, he thought it was acceptable if the conditions seem to me to

be such that economic improvement would contribute both to the well-being of

the ordinary people and to the chance of movement towards a politically free

society (Friedman, 1975b, p. 596). Of course, this position begs a lot of questions

(such as whether advice that improves economic conditions might slow the transition to a free society) and has a lot of embedded assumptions (for example that

Downloaded by [University of York] at 08:20 18 August 2014

Hayek, Friedman, and Buchanan

365

the modernization thesis is correct). But it is not wholly unreasonable, even if it

might not be our preferred response.

Aside from his stated positions on Pinochets regime, three critical aspects of

Friedmans political and economic thought support the conclusion that Friedman

would be wary of Hayeks transitional dictatorships. The first is Friedmans argument for rules over discretion in monetary policy. He thought that a monetary

authority with discretionary power was a potent tool for controlling and

shaping the economyand even destroying both the economy and society (Friedman, 1962a, p. 39; Friedman, 1962b, p. 429). Instead, Friedman supported a

system that will provide a monetary framework for a free enterprise economy

yet be incapable of being used as a source of power to threaten economic and political freedom (Friedman, 1962a, p. 51). Second, Friedman worried that a centralized state with concentrated power was dangerous to the proper ends of

government. For example, he claimed that preserving individual freedom

requires that power be dispersed, that it be prevented from accumulating in any

one person or group of people (Friedman, 1962b, p. 429). Hence, he favored

limited government where rules held sway rather than men and their discretionary

power. Friedmans views on how central monetary authorities should approach

monetary policy amount to a particular application of his larger position in

favor of rules over discretion, a position that applies equally to dictators. The

empowered dictator will have at least the same difficulties as the discretionary

central banker with the power to save or destroy: their historical records are not

great. The information problem suggests it is impossible over the long run even

for those with benevolent intentions to get things right, and political pressure

and individual interest can lead to purposeful bad behavior (Friedman, 1962a,

1962b; Friedman & Schwartz, 1963). Of course, Hayek typically agreed; hence

he favored limited government and markets as the first-best. However, Friedman

thought that there were problems with Hayeks second-best argument too.

Friedman did not think that authoritarianism was the only possible answer to

the problem of creating a free society. He thought it was a mythfueled by

Chiles successthat only an authoritarian regime can successfully implement

a free-market policy. Indeed, he thought that military juntas are especially unlikely to do so given that they are hierarchical and organized from the top down

whereas a free market is the reverse. It is voluntaristic, authority is dispersed; bargaining not submission to orders is the watchword; it is organized from the bottom

up (Friedman, 1982). This is why Friedman called Chile the exception, not the

rule (Friedman, 1982) and on more than one occasion called that countrys economic and more importantly political transformation a miracle (Friedman, 1982;

see also Friedman, 1991a, 1991b). Indeed, Friedman thought in the early 1980s

that even the miracle of Chile will not last unless the military government is

replaced by a civilian government dedicated to political liberty . . . Otherwise,

sooner or laterand probably sooner rather than latereconomic freedom will

succumb to the authoritarian character of the military (Friedman, 1982).

Friedman did think that the spread of economic liberty helped promote political liberty. Yet he saw economic freedom as being merely necessary rather than

necessary and sufficient (Friedman, 1982; see also Friedman 1962a, 1962b). And,

perhaps surprisingly, Friedman also thought that political freedom in turn is a

Downloaded by [University of York] at 08:20 18 August 2014

366 J. Meadowcroft & W. Ruger

necessary condition for the long-term maintenance of economic freedom (Friedman, 1982). Therefore, again, Friedmans views fail to suggest dictatorship was

the answerat least in the long-term. Like Hayek, there are deontological and

consequentialist dimensions to Friedmans case for liberty, but Friedman did

seem ultimately to subscribe to the view that liberty is intrinsically important,

even if it is very difficult to untangle the intrinsic value of freedom from the outcomes it produced (Friedman, 1978).

It is unlikely that Friedman would have seen transitional dictatorships as part

of a necessary short-term solution either, since he did not see a slippery road to

serfdom. Friedman (1982) argued that although politically free societies have

moved in the direction of collectivism, none has gone all the way except through

the force of arms. Thus, one can infer that he would have rejected Hayeks

schema, as formally represented in Figures 1 and 2 of Farrant & McPhail (2014),

according to which transitional dictatorship could be necessary to stem the slide

to totalitarian democracy. Friedman did worry that political freedom might lead

to an erosion of economic freedom via an overgrown government sector (see Friedman, 1975a), and in an interview with Liberty Fund (Friedman, 2003) he expressed

approval for Hong Kongs non-democratic but economically liberal system. These

remarks do not, however, amount to an endorsement of Hayeks belief in transitional dictatorship as an effective route to freedom.

4. Conclusion

As classical liberals, Hayek, Buchanan and Friedman all saw that democratic politics offered possibilities for both liberation and exploitation. Politics was the

process by which socialism and communism could be challenged, ultimately

defeated and replaced with a liberal order; but it could also be the process by

which majorities and minorities engaged in legalized plunder of the property of

others.

Hayeks view that liberty was only instrumentally valuable, and his resultant

rejection of a rights-based approach, left him with no basis on which to demarcate

the legitimate actions of the state. From this it appears to follow that any action of

the government could be justified on instrumental groundsand this, indeed,

seems to have been Hayeks position vis-a`-vis Pinochet. While Hayek had a relatively sophisticated theory of transitional dictatorship to justify this position,

Friedmans analysis of the implications of discretionary power for freedom and

for effective public policy provides a good basis for rejecting this Hayekian

position.

Hayeks case should serve as a warning to scholars who pursue careers as

public intellectuals that the compromises they make in the public arena may

live as long as their more considered contributions to the world of ideas. It

should also serve as a warning of the dangers that arise when individual liberty

is seen as one value among many, rather than a universal and inviolable principle.

References

Buchanan, J.M. (1974) The Limits of Liberty (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Downloaded by [University of York] at 08:20 18 August 2014

Hayek, Friedman, and Buchanan

367

Buchanan, J.M. (1977) Freedom in Constitutional Contract: Perspectives of a Political Economist

(College Station: Texas A&M University Press).

Buchanan, J.M. (2007) Economics from the Outside In (College Station: Texas A&M University

Press).

Chilean National Commission on Truth and Reconciliation (1993) Report, Volume 1 (Notre Dame:

Notre Dame Law School).

Farrant, A. & McPhail, E. (2014) Can a dictator turn a constitution into a can-opener? F.A. Hayek

and the alchemy of transitional dictatorship in Chile, Review of Political Economy, 26(3), pp.

331 348.

Friedman, M. (1962a) Capitalism and Freedom (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Friedman, M. (1962b) Should there be an independent monetary authority?, in: L.B. Yeager (Ed) In

Search of a Monetary Constitution (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

Friedman, M. (1975a) New York City, Newsweek, 17 November.

Friedman, M. (1975b) Response to Letter from Unnamed Professor Maroon (16 July). Reprinted in:

M. Friedman & R.D. Friedman, Two Lucky People: Memoirs (Chicago: University of Chicago

Press, 1998).

Friedman, M. (1976) Reply, Newsweek 14 June. Reprinted in M. Friedman & R. D. Friedman, Two

Lucky People: Memoirs (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998).

Friedman, M. (1977) My reply to letters in the New York Times 14 March. Reprinted in: M. Friedman & R.D. Friedman, Two Lucky People: Memoirs (Chicago: University of Chicago Press,

1998).

Friedman, M. (1978) What belongs to whom?, Newsweek, 13 March. p. 71.

Friedman, M. (1982) Free markets and the generals, Newsweek, 25 January, p. 59.

Friedman, M. (1991a) Economic freedom, human freedom, political freedom, Smith Center Inaugral

Lecture, California State. 1 November. Available at http://www.cbe.csueastbay.edu/~sbesc/

frlect.html (accessed 28 June 2014).

Friedman, M. (1991b) The drug war as a socialist enterprise, Keynote address at the Fifth International Conference on Drug Policy Reform, Washington, DC, 16 November. Available at

http://www.druglibrary.org/special/friedman/socialist.htm (accessed 28 June 2014).

Friedman, M. (2000) Interview The Commanding Heights, PBS Television [transcript available

at: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/commandingheights/shared/minitext/int_miltonfriedman.html

(accessed 28 June 2014).

Friedman, M. (2003) Interview The Intellectual Portrait Series: A Conversation with Milton Friedman (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund). Available at http://oll.libertyfund.org/index.php?option=

com_staticxt&staticfile=show.php%3Ftitle=975&Itemid=29 (accessed 28 June 2014).

Friedman, M. & Friedman, R. (1998) Two Lucky People: Memoirs (Chicago: University of Chicago

Press).

Friedman, M. & Schwartz, A. (1963) A Monetary History of the United States, 1867 1960 (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

Hayek, F.A. (1960) The Constitution of Liberty (London: Routledge).

Hayek, F.A. (1976) The Mirage of Social Justice (London: Routledge).

Harberger, A. (1976) Setting the record straight on Chile, in: M. Friedman & R.D. Friedman, Two

Lucky People: Memoirs (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998).

Klein, N. (2007) The Shock Doctrine (Toronto: Knopf).

Kukathas, C. (1989) Hayek and Modern Liberalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

McCloskey, D. (2003) Milton, Eastern Economic Journal, 29, pp. 143146.

Meadowcroft, J. (2011) James M. Buchanan (New York: Continuum).

Pinochet, A. (1975) private letter, 16 May, 1975, in: M. Friedman & R.D. Friedman, Two Lucky

People: Memoirs (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998).

Ruger, W. (2011) Milton Friedman (New York: Continuum).

Valdes, J.G. (1995) Pinochets Economists: The Chicago School in Chile (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press).

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Kramer: Rights Without Trimmings (1998)Document106 pagesKramer: Rights Without Trimmings (1998)Liga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- Common Law Trust Foreign Sovereign Immunity Act Defined Public Notice/Public RecordDocument3 pagesCommon Law Trust Foreign Sovereign Immunity Act Defined Public Notice/Public Recordin1or100% (2)

- Doyle, Kant, Liberal LegaciesDocument32 pagesDoyle, Kant, Liberal LegaciesMatheus LamahPas encore d'évaluation

- Goodhart IntroDocument8 pagesGoodhart IntroDr-Shanker SampangiPas encore d'évaluation

- Corozal South EastDocument166 pagesCorozal South EastGarifuna NationPas encore d'évaluation

- Salvador Cienfuegos Zepeda IndictmentDocument9 pagesSalvador Cienfuegos Zepeda IndictmentChivis Martinez100% (1)

- Wiley Philosophy & Public Affairs: This Content Downloaded From 200.89.140.130 On Wed, 21 Mar 2018 19:59:11 UTCDocument32 pagesWiley Philosophy & Public Affairs: This Content Downloaded From 200.89.140.130 On Wed, 21 Mar 2018 19:59:11 UTCMica FerriPas encore d'évaluation

- This Content Downloaded From 201.234.181.53 On Fri, 01 Jul 2022 17:56:05 UTCDocument25 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 201.234.181.53 On Fri, 01 Jul 2022 17:56:05 UTCbrandon abella gutierrezPas encore d'évaluation

- The Liberalism of Care: Community, Philosophy, and EthicsD'EverandThe Liberalism of Care: Community, Philosophy, and EthicsPas encore d'évaluation

- Civil Society in India: Democratic Space or The Extension of Elite Domination?Document29 pagesCivil Society in India: Democratic Space or The Extension of Elite Domination?Seema DasPas encore d'évaluation

- Week 3 - Jurkevics and BenhabibDocument15 pagesWeek 3 - Jurkevics and BenhabibErnest Roura SolerPas encore d'évaluation

- Waligorski Democracy 1990Document26 pagesWaligorski Democracy 1990Oluwasola OlaleyePas encore d'évaluation

- CLASE 4 Doyle - Kant, Liberal Legacies, and Foreign AffairsDocument32 pagesCLASE 4 Doyle - Kant, Liberal Legacies, and Foreign AffairsGuillermo GalloPas encore d'évaluation

- Deliberative Democracy Essays On Reason and PoliticsDocument478 pagesDeliberative Democracy Essays On Reason and PoliticsMariana Mendívil100% (4)

- The Origins of Liberty: Political and Economic Liberalization in the Modern WorldD'EverandThe Origins of Liberty: Political and Economic Liberalization in the Modern WorldPas encore d'évaluation

- Neoliberal PopulismDocument6 pagesNeoliberal PopulismbgultekinaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Neoliberal Revolution and Thatcherite Social PolicyDocument25 pagesThe Neoliberal Revolution and Thatcherite Social PolicyhannekoningsPas encore d'évaluation

- Fukuyama 2011Document12 pagesFukuyama 2011Gabriela MachadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Machiavelli Against the Cambridge School's View of RepublicanismDocument30 pagesMachiavelli Against the Cambridge School's View of RepublicanismRikshika KashyapPas encore d'évaluation

- The United Nations Democracy Agenda: A conceptual historyD'EverandThe United Nations Democracy Agenda: A conceptual historyPas encore d'évaluation

- Critical TheoryDocument4 pagesCritical TheorySaranjam KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Paper On Classical LiberalismDocument4 pagesResearch Paper On Classical Liberalismacpjxhznd100% (1)

- Cambridge University Press Review of International StudiesDocument20 pagesCambridge University Press Review of International StudiesIkbal PebrinsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Warren S. Gramm - Chicago Economics. From Individualism True To Individualism FalseDocument24 pagesWarren S. Gramm - Chicago Economics. From Individualism True To Individualism FalseCesar Jeanpierre Castillo GarciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Critical theory and sociological theory: On late modernity and social statehoodD'EverandCritical theory and sociological theory: On late modernity and social statehoodPas encore d'évaluation

- The Dark Side of The Relationship Between The Rule of Law and LiberalismDocument38 pagesThe Dark Side of The Relationship Between The Rule of Law and LiberalismKaiyuan ChenPas encore d'évaluation

- Political Science SyllabusDocument3 pagesPolitical Science SyllabusArjun NayyarPas encore d'évaluation

- MORRICE (2000) - The Liberal-Communitarian Debate in Contemporary Political Philosophy and Its Significance For International RelationsDocument20 pagesMORRICE (2000) - The Liberal-Communitarian Debate in Contemporary Political Philosophy and Its Significance For International RelationsVitor LuocasPas encore d'évaluation

- Morgenthau 1952Document49 pagesMorgenthau 1952是Pas encore d'évaluation

- Morgenthau 1952Document29 pagesMorgenthau 1952是Pas encore d'évaluation

- LacherandGermann BeforeHegemony2012Document27 pagesLacherandGermann BeforeHegemony2012PGIndikaPas encore d'évaluation

- Thesis LiberalismDocument8 pagesThesis LiberalismCanYouWriteMyPaperUK100% (2)

- Readings in Public Choice and Constitutional Political EconomyDocument616 pagesReadings in Public Choice and Constitutional Political EconomyAbdullahKadirPas encore d'évaluation

- Capitalism, Socialism, and Freedom by Peter BerkowitzDocument11 pagesCapitalism, Socialism, and Freedom by Peter BerkowitzHoover Institution100% (4)

- Liberalism WorkingDocument53 pagesLiberalism WorkingMohammad ShakurianPas encore d'évaluation

- SIBU620-Week 8-Michael DoyleDocument32 pagesSIBU620-Week 8-Michael DoyleOsman ŞentürkPas encore d'évaluation

- Philosophy Faculty Reading List and Course Outline 2019-2020 Part IB Paper 07: Political Philosophy SyllabusDocument17 pagesPhilosophy Faculty Reading List and Course Outline 2019-2020 Part IB Paper 07: Political Philosophy SyllabusAleksandarPas encore d'évaluation

- Political BehaviorDocument6 pagesPolitical BehaviorCherub DaramanPas encore d'évaluation

- Does Modernization Require Westernization? - Deepak Lal (2000) The Independant ReviewDocument21 pagesDoes Modernization Require Westernization? - Deepak Lal (2000) The Independant ReviewAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriPas encore d'évaluation

- Transnational Democracy Theories and Prospects Research ArticleDocument51 pagesTransnational Democracy Theories and Prospects Research ArticleFranco van WykPas encore d'évaluation

- Monografia Sobre MorghentauDocument94 pagesMonografia Sobre MorghentauRicardo Zortéa VieiraPas encore d'évaluation

- GUNNELL, John G. The Genealogy of American PluralismDocument14 pagesGUNNELL, John G. The Genealogy of American PluralismVinicius FerreiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Anarchism, Libertarianism and Environmentalism: Anti-Authoritarian Thought and The Search For Self-Organizing Societies Damian Finbar White and Gideon KossoffDocument16 pagesAnarchism, Libertarianism and Environmentalism: Anti-Authoritarian Thought and The Search For Self-Organizing Societies Damian Finbar White and Gideon KossofflibermayPas encore d'évaluation

- U4 - Michael Doyle - Kant Liberal Legacies and Foreign Affairs, Part IDocument32 pagesU4 - Michael Doyle - Kant Liberal Legacies and Foreign Affairs, Part ISofía MormandiPas encore d'évaluation

- Tullock) - A Rehabilitation of The Public Interest TheoryDocument20 pagesTullock) - A Rehabilitation of The Public Interest Theoryluciano melo francoPas encore d'évaluation

- Journal of Democracy 2007 1Document15 pagesJournal of Democracy 2007 1James MuldoonPas encore d'évaluation

- Andreas Niederberger_ Philipp Schink - Republican Democracy_ Liberty, Law and Politics-Edinburgh University Press (2013)Document342 pagesAndreas Niederberger_ Philipp Schink - Republican Democracy_ Liberty, Law and Politics-Edinburgh University Press (2013)Rodrigo CorderoPas encore d'évaluation

- Lele 2008 Reflections On Theory and Practice Final No Mark Ups PDFDocument41 pagesLele 2008 Reflections On Theory and Practice Final No Mark Ups PDFPrathamanantaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2005HOPEDocument29 pages2005HOPEPatrick AlvesPas encore d'évaluation

- Machiavelli Against RepublicanismDocument30 pagesMachiavelli Against RepublicanismLaurie Kladky100% (1)

- Chanakaya National Law University, Patna: Roject ORKDocument24 pagesChanakaya National Law University, Patna: Roject ORKPrasenjit TripathiPas encore d'évaluation

- Political Science and the Concept of "The Public InterestDocument30 pagesPolitical Science and the Concept of "The Public InterestPaola BFPas encore d'évaluation

- Changing Paradigms of Citizenship and the Exclusiveness of the DemosDocument25 pagesChanging Paradigms of Citizenship and the Exclusiveness of the Demossharpie_123Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Essential HayekDocument88 pagesThe Essential HayekJesús José Mañas Cruz100% (1)

- What's Wrong With Media MonopoliesDocument19 pagesWhat's Wrong With Media MonopoliesElena CodenPas encore d'évaluation

- Week 6 A The English SchoolDocument6 pagesWeek 6 A The English SchoolBrayan Estiven Laverde TorresPas encore d'évaluation

- MPS 01 Block 05 PDFDocument64 pagesMPS 01 Block 05 PDFSarvesh KysPas encore d'évaluation

- Doyle, Kant, Liberal Legacies and Foreign AffairsDocument32 pagesDoyle, Kant, Liberal Legacies and Foreign AffairsMarcPas encore d'évaluation

- 019 Beyond Realism and Marxism - 71Document8 pages019 Beyond Realism and Marxism - 71Davide SchmidPas encore d'évaluation

- A Study Guide for Political Theories for Students: LIBERTARIANISMD'EverandA Study Guide for Political Theories for Students: LIBERTARIANISMPas encore d'évaluation

- Rawls, Liberalism and Democracy (Skorupski)Document26 pagesRawls, Liberalism and Democracy (Skorupski)Liga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- Law and Violence (Menke)Document18 pagesLaw and Violence (Menke)Liga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- Political Liberalism: A Kantian View (Forst)Document22 pagesPolitical Liberalism: A Kantian View (Forst)Liga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- Rawlsian Liberalism and The Privatization of ReligionDocument27 pagesRawlsian Liberalism and The Privatization of ReligionLiga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- On The Share of Inheritance in Aggregate Wealth: Europe and The USA, 1900 - 2010Document22 pagesOn The Share of Inheritance in Aggregate Wealth: Europe and The USA, 1900 - 2010Liga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- Manin Political Deliberation & Adversarial PrincipleDocument12 pagesManin Political Deliberation & Adversarial PrincipleLiga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- Autonomy and Disagreement About Justice in Political Liberalism (Weithman)Document28 pagesAutonomy and Disagreement About Justice in Political Liberalism (Weithman)Liga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- Shapiro Collusion in Restraint of Democracy Against Political DeliberationDocument8 pagesShapiro Collusion in Restraint of Democracy Against Political DeliberationLiga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- Wellbeing Inequality and Preference Heterogeneity: Byk D, , M F and E SDocument29 pagesWellbeing Inequality and Preference Heterogeneity: Byk D, , M F and E SLiga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lupia&Norton - Inequality - Is - Always in The Room - Language - Power - in - Deliberative - DemocracyDocument13 pagesLupia&Norton - Inequality - Is - Always in The Room - Language - Power - in - Deliberative - DemocracyLiga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- Charles Larmore: Pluralism and Reasonable Disagreement (1994)Document19 pagesCharles Larmore: Pluralism and Reasonable Disagreement (1994)Liga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria Política100% (1)

- Landemore Deliberative Democracy As Open Not (Just) Representative DemocracyDocument13 pagesLandemore Deliberative Democracy As Open Not (Just) Representative DemocracyLiga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- Pareto and The Upper Tail of The Income Distribution in The UK: 1799 To The PresentDocument28 pagesPareto and The Upper Tail of The Income Distribution in The UK: 1799 To The PresentLiga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- O'Neill Consistency in ActionDocument24 pagesO'Neill Consistency in ActionLiga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- Vlastos: Equality and Justice (1962)Document7 pagesVlastos: Equality and Justice (1962)Liga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- Draper (2007) Possessing Slaves: Ownership, Compensation and Metropolitan SocietyDocument29 pagesDraper (2007) Possessing Slaves: Ownership, Compensation and Metropolitan SocietyLiga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- Steiner: Choice and Circumstance (1997)Document17 pagesSteiner: Choice and Circumstance (1997)Liga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- O'Neill Emperor's New Clothes (2003)Document22 pagesO'Neill Emperor's New Clothes (2003)Liga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- O'Neill: Vindicating ReasonDocument15 pagesO'Neill: Vindicating ReasonLiga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- List & Valentini: Freedom As Independence (2016)Document32 pagesList & Valentini: Freedom As Independence (2016)Liga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- IMF NeoliberalismDocument4 pagesIMF NeoliberalismZerohedgePas encore d'évaluation

- Thomas: Rawls Piketty and The New Inequality (2016)Document47 pagesThomas: Rawls Piketty and The New Inequality (2016)Liga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- Flikschuh (2008) Reason, Right and Revolution: Locke and KantDocument30 pagesFlikschuh (2008) Reason, Right and Revolution: Locke and KantLiga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- Petroni: John Rawls and The Social MaximumDocument22 pagesPetroni: John Rawls and The Social MaximumLiga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- Property RightsDocument68 pagesProperty RightsstriiderPas encore d'évaluation

- Wilesmith: Social Equality and The Coporate Governance of A Property-Owning DemocracyDocument21 pagesWilesmith: Social Equality and The Coporate Governance of A Property-Owning DemocracyLiga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- Baptista & Merrill: Introduction To Property-Owning DemocracyDocument20 pagesBaptista & Merrill: Introduction To Property-Owning DemocracyLiga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- Petroni: John Rawls and The Social MaximumDocument22 pagesPetroni: John Rawls and The Social MaximumLiga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- Waldron The Vanishing Europe of Jurgen Habermas (2015)Document6 pagesWaldron The Vanishing Europe of Jurgen Habermas (2015)Liga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaPas encore d'évaluation

- Direct Roles and Functions of ICjDocument24 pagesDirect Roles and Functions of ICjEswar StarkPas encore d'évaluation

- Argosino Martee Socio Eco IssuesDocument4 pagesArgosino Martee Socio Eco IssuesKristin ArgosinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Samson Vs DawayDocument1 pageSamson Vs DawayJoshua Quentin TarceloPas encore d'évaluation

- People of The Philippines Vs Jose Vera (G.R. No. L-45685, November 16, 1937)Document3 pagesPeople of The Philippines Vs Jose Vera (G.R. No. L-45685, November 16, 1937)Ei Bin100% (2)

- History - ChavakkadDocument3 pagesHistory - ChavakkadChasity WrightPas encore d'évaluation

- Malabunga, Jr. vs. Cathay Pacific Steel CorporationDocument18 pagesMalabunga, Jr. vs. Cathay Pacific Steel CorporationElmira Joyce PaugPas encore d'évaluation

- EKuhipath-eKuhiCA Current Affairs, Monthly Magazine, October2023Document110 pagesEKuhipath-eKuhiCA Current Affairs, Monthly Magazine, October2023temp255248Pas encore d'évaluation

- ...Document18 pages...stream socialPas encore d'évaluation

- The Mid-Day Meal Scheme in Four Districts of Madhya PradeshDocument21 pagesThe Mid-Day Meal Scheme in Four Districts of Madhya PradeshVikas SamvadPas encore d'évaluation

- NOTIFICATION CT TM 2019 English PDFDocument40 pagesNOTIFICATION CT TM 2019 English PDFNarender GillPas encore d'évaluation

- John Giduck List of False Military Claims - FINALDocument12 pagesJohn Giduck List of False Military Claims - FINALma91c1anPas encore d'évaluation

- Hacienda Bigaa Vs ChavezDocument5 pagesHacienda Bigaa Vs ChavezAnn Alejo-Dela TorrePas encore d'évaluation

- Corruption, Ethics and Government ReviewedDocument11 pagesCorruption, Ethics and Government ReviewedratriPas encore d'évaluation

- Subiecte Cangurul LingvistDocument5 pagesSubiecte Cangurul LingvistANDREEA URZICAPas encore d'évaluation

- Indira Gandhi BiographyDocument5 pagesIndira Gandhi BiographyIswaran KrishnanPas encore d'évaluation

- Rs 60,00,000 Crore Thorium Scam - Extended Into 2017Document18 pagesRs 60,00,000 Crore Thorium Scam - Extended Into 2017hindu.nation100% (1)

- Non Refoulement PDFDocument11 pagesNon Refoulement PDFM. Hasanat ParvezPas encore d'évaluation

- Visitor Visa (Subclass 600) AUSTDocument5 pagesVisitor Visa (Subclass 600) AUSTgiesengalaarmelPas encore d'évaluation

- Land Dispute Leads to Contempt CaseDocument5 pagesLand Dispute Leads to Contempt CaseRuab PlosPas encore d'évaluation

- CCFOP v. Aquino coconut levy fundsDocument3 pagesCCFOP v. Aquino coconut levy fundsMikaela PamatmatPas encore d'évaluation

- Judicial ReviewDocument13 pagesJudicial ReviewYash Kamra100% (1)

- From Indio To FilipinoDocument84 pagesFrom Indio To FilipinoCherrie MaePas encore d'évaluation

- Definition of PoliticsDocument13 pagesDefinition of PoliticsMaRvz Nonat Montelibano100% (1)

- Was The US Founded On Capitalism?Document3 pagesWas The US Founded On Capitalism?Newnac100% (1)

- The History of Japan's Seizure of Dokdo Island During the Invasion of KoreaDocument33 pagesThe History of Japan's Seizure of Dokdo Island During the Invasion of KoreaAxel Lee WaldorfPas encore d'évaluation

- Borromeo v. Civil Service Commission (1991) DoctrineDocument3 pagesBorromeo v. Civil Service Commission (1991) Doctrinepoppy2890Pas encore d'évaluation

- Swedish Media Versus Assange 11-11-11 Press BombDocument22 pagesSwedish Media Versus Assange 11-11-11 Press Bombmary engPas encore d'évaluation