Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Formation of Armenian Legion Article Published PDF

Transféré par

Anush HovhannisyanDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Formation of Armenian Legion Article Published PDF

Transféré par

Anush HovhannisyanDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The Historical Journal

http://journals.cambridge.org/HIS

Additional services for The

Historical Journal:

Email alerts: Click here

Subscriptions: Click here

Commercial reprints: Click here

Terms of use : Click here

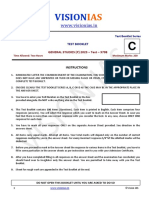

FRENCH AND BRITISH POST-WAR IMPERIAL

AGENDAS AND FORGING AN ARMENIAN

HOMELAND AFTER THE GENOCIDE: THE

FORMATION OF THE LGION D'ORIENT IN

OCTOBER 1916

ANDREKOS VARNAVA

The Historical Journal / Volume 57 / Issue 04 / December 2014, pp 997 - 1025

DOI: 10.1017/S0018246X13000605, Published online: 12 November 2014

Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0018246X13000605

How to cite this article:

ANDREKOS VARNAVA (2014). FRENCH AND BRITISH POST-WAR IMPERIAL

AGENDAS AND FORGING AN ARMENIAN HOMELAND AFTER THE

GENOCIDE: THE FORMATION OF THE LGION D'ORIENT IN OCTOBER 1916.

The Historical Journal, 57, pp 997-1025 doi:10.1017/S0018246X13000605

Request Permissions : Click here

Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/HIS, IP address: 129.96.82.202 on 14 Nov 2014

The Historical Journal, , (), pp. Cambridge University Press

doi:./SX

F R E N C H A N D B R I T I S H P O S T - WA R

IMPERIAL AGENDAS AND FORGING

AN ARMENIAN HOMELAND AFTER THE

GENOCIDE: THE FORMATION OF THE

L G I O N DO R I E N T I N O C T O B E R *

A N D R E KO S VA R N AVA

Flinders University

A B S T R A C T . In October , the French government agreed with Armenian political elites

to establish a Lgion of Armenian volunteers in British Cyprus to ght the common Ottoman enemy.

Despite British, French, and even Armenian rejections of such a Lgion during different times

throughout and early , all sides overcame earlier concerns. Understanding how they

managed to overcome these concerns will allow for this little-known episode in the history of the Great

War in the eastern Mediterranean to contribute to the knowledge on () the complex French and

British wartime stances towards this region, driven by imperialism and humanitarianism; () the

ability of local elites to draw concessions from the Allies; () the important role played by local British

and French colonial and military ofcers; and () broader historiographical debates on the responses

to the Armenian Genocide. This article explores the origins of how the Entente co-opted Armenians

in their eastern Mediterranean campaigns, but also made them into pawns in the French and British

reinvention of their imperial rivalry in this region in order to achieve their post-war imperialist

agendas.

I

On October , in the comfort of the French Embassy in London, Boghos

Nubar Pasha, the founder and rst president of the Armenian General

Benevolent Union (), and the head of the Armenian National Delegation in Paris from December , was shown the SykesPicot Agreement.

The British and French diplomats present at the meeting, Mark Sykes and

Francois Georges-Picot respectively, the co-authors of the SykesPicot Agreement, led Nubar to understand that the Armenian-populated areas of the

School of International Studies, Flinders University, GPO Box , Adelaide , South Australia

andrekos.varnava@inders.edu.au

* I would like to acknowledge the following people in the making of this article: Dr David

Close, Dr Matthew Fitzpatrick, Dr Evan Smith, and Ms Justine Tilman from Flinders University,

and the anonymous reviewers for The Historical Journal.

A N D R E KO S VA R N AVA

Ottoman Empire would be divided into two parts after the war: one composing

the eastern vilayets of Van, Erzerum, Bitlis, Dersim, and Trabzon, under Russian

control, and the other including Cilicia and the three western vilayets of Sivas,

Kharput, and Diayarbekir, under French control. Thus, the Armenianpopulated areas of the Ottoman Empire would come under the protection of

two of the Allied powers of the Great War. Nubar recalled that Georges-Picot

had asserted that the French would be willing to grant the Armenians an

autonomous state under their control, but the Armenians should earn the

right to the liberation of their fatherland, by providing volunteers for a planned

expedition in Asia Minor. Accordingly, they agreed to form the Lgion

dOrient, with the following particulars:

. The constitution of the Lgion dOrient aimed to have Armenians contribute

to the liberation of their fatherland in exchange for granting them new

entitlements in line with their national aspirations.

. The Armenian Lgionnaires would only ght against the Ottoman Empire and

only on the soil of their fatherland.

. The Armenian Lgion would constitute the future nucleus of the Armenian army

in the future Armenian state.

This agreement planned for the establishment of a French protectorate over

the Armenian-populated areas of western Armenia in exchange for creating an

Armenian Lgion in the French army and thus contributing to an Allied victory

against the Ottoman Empire.

This article does not deal with the operational history of the Armenian

Lgion, yet it is important to understand its wider military and geo-strategic

signicance once operational. Six battalions with roughly men were formed

and trained on Cyprus, and those that served in the Palestine Campaign,

specically at the battle of Arara, exhibited good ghting qualities according

to General Edmund Allenby, who was in charge of the campaign. The Lgion

dOrient, which also contained Syrian Arabs (initially trained on Cyprus,

but later moved to Syria), was renamed Armenian Lgion after the armistice

when it formed a part of the French Army of Occupation of Cilicia and its

surrounding areas. Its role in this capacity has been the subject of some

Boghos Nubar memorandum on creation of Lgion dOrient, Dec. , London, The

National Archives (TNA), Foreign Ofce (British) (FO) //; Boghos Nubar, Note on

the circumstances and conditions under which the Lgion dOrient was created in ,

Dec. , Paris, Nubarian Library (NL), Lgion dOrient, Armenian Volunteers,

Ibid.

Miscellany, box .

Despatch from General Allenby, Oct. , London Gazette, Dec. , TNA, War

Ofce (British) (WO) /; Boghos Nubar, Note, Dec. , NL, Lgion dOrient,

Armenian Volunteers, Miscellany, box .

See Simon Jackson, Diaspora politics and developmental empire: the Syro-Lebanese at the

League of Nations, Arab Studies Journal, (), pp. , at pp. .

See N. E. Bou-Nacklie, Les troupes speciales: religious and ethnic recruitment,

, International Journal of Middle East Studies, (), pp. ; Eliezer

F O R M I N G T H E L G I O N DO R I E N T

controversy, both in relation to the Franco-Turkish War and the subsequent

exodus of Armenians. Albeit in a limited way, the Lgion has also been discussed in relation to the Armenian Genocide (see below). Yet, despite some

works on its role in these events, nothing denitive has been published in the

English language on its formation (particularly of the Armenian component)

in October , let alone the rather long build-up that included numerous

rejections.

This article uses British, French, Armenian, and Cypriot archival sources as

well as British, French, and Turkish language historiography to reconstruct the

story of the formation of the Lgion dOrient in October . It attempts to

show that the Lgions formation transpired after many rejections rst from

the British, then the French, and then from Armenian political elites during a

transition period for British and French policy-makers in relation to their approach to the war in the Near and Middle East and their post-war role there, as

well as for Armenians during the implementation of the Genocide. This argument will contradict the claims of Armenian Genocide denialists that the

Lgion was established because of French and British support for Armenian

aspirations in a conspiracy to topple the Ottoman government, or as an Allied

humanitarian response to the Armenian Genocide. The Lgion dOrient was

formed to serve the British and French (in particular) strategic-military agenda

against the Ottoman Empire and post-war French imperial ambitions as these

had evolved in spring in the SykesPicot Agreement. The hope of

Armenian political elites for a secure autonomous homeland was merely a

corollary of these broader French and British agendas.

There is little English-language historiography on the Lgion dOrient

and what there is betrays a deep politicization: Turkish authors primarily use

its existence to justify the Ottoman governments deportation policy; while

Armenian authors portray it as a celebration of Armenian national awakening.

Most publications lack a comprehensive archival research base. More recently,

Yucel Guclu, an employee of the Turkish embassy in Washington, published a

potted account of the rst proposals for the establishment of an Armenian

Lgion and the implications on the proposal to land forces at Alexandretta.

Tauber, La Lgion dOrient et La Lgion Arabe (The Lgion dOrient and the Arab Lgion),

Revue Franaise dHistorie dOutre-Mer, (), pp. .

Stanford Shaw, The Armenian Lgion and its destruction of the Armenian community of

Cilicia, in Turkkaya Ataov, ed., The Armenians in the late Ottoman period (Ankara, ),

pp. .

Ibid.; see also Mim Kemal Oke, The Armenian question, (Nicosia, ),

pp. .

Robert O. Krikorian, In defence of the homeland: New England Armenians and the

Lgion dOrient, in Marc A. Mamigonian, ed., Armenians of New England: celebrating a culture and

preserving a heritage (Belmont, MA, ), pp. . Not much academic material exists,

mostly memoirs. Of note is the exhibit honouring the Armenian Lgion titled Forgotten

heroes: the Armenian Lgion and the Great War, which was held in the Armenian Library and

Museum of America from Sept. to the end of Feb. .

A N D R E KO S VA R N AVA

As part of justifying his denial of an Ottoman Genocide of Armenians, he

claimed that the British and Armenians (i.e. all of them en masse) colluded to

topple the Ottoman Empire, thus justifying the relocation of the Armenians.

His account fails to explore let alone identify the reasons the British, French,

and even Armenian elites rejected a Lgion during various periods in and

early , nor does he explore the circumstances that led to the creation of

the Lgion in October . The exceptions are Akaby Nassibians book from

, which provides much narrative and not as much analysis and context as

the less detailed account in Donald Bloxhams study.

The Turkish-language historiography on the Lgion dOrient is no better,

centring on the work of Armenian Genocide denialists Ulvi Keser and

Halil Aytekin. The former produced two monographs on the subject, using

the Turkish Military Archives, yet no French archives, while the latter accessed

archives from Turkey, Britain, and France, but was far more schematic and

patchy. Both were fundamentally awed because they use the existence of the

Lgion, not formed until October , to justify the Ottoman deportation

policy of spring , confusing the chronology of events and the context of

French and British decisions.

There is a broader historiography than that of the Lgion dOrient and

Armenian Genocide, and that is the British recruitment of Ottoman subjects

into the grand coalition against the Central Powers, particularly the Ottoman

Empire. Here, the interconnected and sometimes contradictory themes of rival

imperialisms and nationalisms, the entanglement of humanitarianism and imperialism, and subaltern agency are most important. There is a signicant historiography on the formation of Arabs into ghting units and the Jewish Legion

later in for the purposes of defeating the Ottoman Empire.

The Armenian case differs because it was under French command, but also

because there was a greater level of humanitarianism involved. So, whereas the

British justied encouraging the Arab revolt and the formation of the Jewish

Legion by propagating against the oppression of Ottoman rule, with the

Yucel Guclu, Armenians and the Allies in Cilicia, (Salt Lake City, UT, ),

pp. ; see my review of Gucels book in Reviews in History, () (www.history.ac.uk/

reviews/review/); see also M. Serdar Palabiyik, Establishment and activities of French

Lgion dOrient (Eastern Lgion) in the light of French archival documents, Review of

Armenian Studies, (), pp. .

Akaby Nassibian, Britain and the Armenian question, (London, ),

pp. ; Donald Bloxham, The great game of genocide: imperialism, nationalism and the

destruction of the Ottoman Armenians (Oxford, ), pp. , .

Halil Aytekin, Kbrsta Monarga (Bogaztepe) Ermeni Lejyonu Kamp (Monarga camp of

Armenian Lgion in Cyprus) (Ankara, ); Ulvi Keser, Kbrs, : Fransz Ermeni

kamplar I ngiliz esir kamplar ve Atatrk Kbrs Trk (Cyprus, : French Armenian

camps, British prisoner camps and Kemalist Cypriot Turks) (Istanbul, ); Ulvi Keser, KbrsAnadolu ekseninde Ermeni dogu Lejyonu (Armenian Eastern Lgion in the Cyprus-Anatolia axis)

(Ankara, ).

See David Murphy, The Arab revolt, : Lawrence sets Arabia ablaze (Oxford, );

and Martin Watts, The Jewish Legion and the First World War (New York, NY, ).

F O R M I N G T H E L G I O N DO R I E N T

Armenians both the British and the French had used the Armenian Genocide

to create a public humanitarian response against Ottoman savagery. In his

recent study, Davide Rodogno has argued that European humanitarian interventions in the Ottoman Empire date back to the s, but the humanitarianism usually hid behind the real motivations (and sometimes was an ex post

facto justication), which were usually political, imperial, economic, and/or

strategic, and intervention could only be made if more than one European

power was involved. In the case presented here, the incentive to win the war

was linked to post-war imperial expansion, thus motivating both the French and

the British to form the Lgion dOrient. This explains why the determination to

form it materialized only after the SykesPicot Agreement was signed.

European humanitarianism and imperialism and their links with the

Armenian Question must be understood within the broader Eastern

Question, and specically on how the three Allied powers in the First World

War all had a traditional claim to protecting the Christians in the Ottoman

Empire and a special relationship with the Armenians. This, of course, did not

automatically result in a decision to form the Lgion, since intervention, as

Rodogno showed, needed more than humanitarianism to propel it and was

often an ex post facto justication for intervention.

During the nineteenth century, a corollary of the Eastern Question was

how the Ottoman state recognized the European Powers, particularly the

French and the Russians, as the protectors of the Catholic (Maronite and other

eastern Catholics) and Orthodox Christians respectively. For example, in

the case of the French, the Catholic presence in Syria and to a lesser extent

Palestine propelled French imperial interests in this part of the Ottoman

Empire. The role of protecting Ottoman Christian minorities was extended to

the Armenians, but with signicant differences. Armenian protection was not

guided by religious afliation, although there was a religious dimension to

Russian feeling, particularly earlier in the century, but by liberalism (particularly for the British and French) and imperialism. In the Anglo-Turkish

Davide Rodogno, Against massacre: humanitarian interventions in the Ottoman Empire,

(Princeton, NJ, ). Egypt is an exception to Rodognos interpretation.

Ibid.

After the Crimean War, Russia focused on the Slavic Orthodox Christians in the Balkans.

See Jelena Milojkovic-Djuric, Panslavism and national identity in Russia and in the Balkans,

: images of the self and others (Boulder, CO. and New York, NY, ).

See, for example, ibid.; also Benedict Humphrey Sumner, Russia and the Balkans,

(Oxford, ); and Michael Boro Petrovich, The emergence of Russian panslavism,

(New York, NY, ).

For British liberal imperialism in the Ottoman Empire, see Andrekos Varnava, British

imperialism in Cyprus, : the inconsequential possession (Manchester, ); and

Andrekos Varnava, British and Greek liberalism and imperialism in the long nineteenth

century, in Matthew P. Fitzpatrick, ed., Liberal imperialism in Europe (London, ),

pp. . For information on French liberal imperialism, see J. P. Daughton, An empire

divided. Religion, republicanism, and the making of French colonialism, (Oxford, );

A N D R E KO S VA R N AVA

Convention and in the Treaty of Berlin, both of , the British government

led the way in compelling the Ottoman Empire to agree to reforms for its

Christian communities in its eastern provinces a clear reference to Armenians.

Lord Beaconselds Conservative government aimed to establish informal

imperial hegemony over Asia Minor and Syria, but this failed because Sultan

Abdul Hamid II refused to implement reforms, and relations between the two

countries deteriorated. Although conservative governments were in power

in both France and Britain at the time, it was British and French liberals

who sympathized more with the ambitions of Armenian secular political elites

for more representation. More generally, most European governments sympathized with the Armenians after the massacres perpetuated against them by

Abdul Hamids regime in the s, yet no action was taken to prevent them at

the time or in the future, with further massacres in . Nevertheless, British

and French governments were able to create much public humanitarian feeling

and action in support of Armenian refugees. For their part, Armenian political elites were inuenced by British, French, and Russian political developments, but especially the revolutionary character of opposition groups in

the latter. But by the eve of the First World War, Armenian political elites,

having set aside violent revolutionary approaches, were closer to the French and

British, and European powers were locked in discussions with the Ottoman

government, now led by the Committee of Union and Progress, on implementing reforms that would benet Armenians in the Ottoman Empire.

This helps explain the readiness of Armenian political elites to seek protection and to align themselves with the Russian, British, and French alliance

during the First World War. Although some Armenians fought in the Ottoman

army, others on the Russo-Ottoman border joined the Russians, while

political elites in Europe and the US advocated a British Armenian Lgion,

for French missionaries in the Ottoman Empire, see Owen White and J. P. Daughton, eds., In

Gods empire: French missionaries and the modern world (Oxford and New York, NY, ), chs. .

Varnava, British imperialism in Cyprus, pp. and .

See also Bloxham, The great game of genocide, pp. , , and .

See, for the British case, the work of the following people in Cyprus: Emma Cons,

Armenian exiles in Cyprus, Contemporary Review, (), pp. ; Patrick Geddes,

Cyprus, actual and possible: a study in the Eastern Question, Contemporary Review, (),

Bloxham, The great game of genocide, pp. .

pp. .

Ibid., pp. . For the reforms issue, see TNA, FO//; British Library

(BL), India Ofce Records (IOR) Political and Secret Annual Files, IOR/L/PS// ;

Political and Secret Annual Files, IOR/L/PS// ; and Political and Secret Annual

Files, IOR/L/PS// .

Sarkis Torossian was one fascinating case. He was in charge of the rst fort at the

Dardanelles entrance and was awarded for his bravery in stopping the British attempt to force

the Dardanelles. He later served in the Lgion dOrient after discovering that family had died

during the Genocide. Sarkis Torossian, From Dardanelles to Palestine: a true story of ve battle fronts

of Turkey and her Allies and a harem romance (Boston, MA, ).

Nassibian, Britain and the Armenian Question, pp. and ; Bloxham, The great game of

genocide, pp. .

F O R M I N G T H E L G I O N DO R I E N T

which the British rejected in March . Consequently, on April ,

Boghos Nubar requested to go to Paris to defend the interests of Ottoman

Armenians because he wished to convince the French government of the need

for the Entente to protect the Armenian population, through incorporating

them into a Syria under French control. The British and French governments

linked the protection of Ottoman Armenians with their own imperial interests

in the eastern Mediterranean. Despite the many decades leading up to the

Great War when such interests were cultivated informally (more formally in

the British cases of Cyprus and Egypt), French and British imperial interests in

the Ottoman Empire remained informal until well into . The entry of the

Ottoman Empire into the war did not result in the start of a serious military

front in any of the areas where either the British or French had imperial

interests. This was despite the fact that originally the plan was to force the

Dardanelles by ships alone and, succeed or fail, land troops at Alexandretta.

This was overlooked instead for landing troops on Gallipoli. Subsequently, the

Armenian Genocide had no impact on British and French war strategy, as their

withdrawal from Gallipoli took them to Salonika. Yet the Gallipoli failure did see

them reconsider their traditional imperial interests on the Ottoman periphery

in the eastern Mediterranean. But even then it took the best part of a year after

the Gallipoli failure for the British and French to start focusing their military

strength there, which helps explain the delays in forming the Lgion dOrient.

The Armenians were pawns in the greater game of post-war French and British

imperial expansion, and thus, as Rodogno has shown for the century before the

Great War, humanitarianism, in this case in relation to the Armenian Genocide,

was not the main motivation for the British and French to take the side of the

Armenians by forming the Lgion.

II

Boghos Nubar rst proposed using Armenians as part of an Allied landing at

Alexandretta in November in order to protect Cilician Armenians, who he

feared would be massacred by the Ottomans in revenge for Armenians near the

Russian border joining the Russian army. The landing at Alexandretta appealed to many British strategic planners, especially General Sir John Maxwell,

Andrekos Varnava, Imperialism rst, the war second: the British, an Armenian Legion,

and deliberations on where to attack the Ottoman Empire, November April ,

Historical Research, Early View () (http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/././abstract).

Cairo to Paris, Apr. , Paris, French Foreign Ministry Archives (FFMA), War

, Turkey, vol. , Armenian, I, Aug. to Dec. . Hereafter, volume in

Arabic numerals and issue in Roman numerals will be provided.

See Varnava, Imperialism rst, the war second.

Boghos Nubar to Kevork V, Paris, July , Vatche Ghazarian, ed. and trans., Boghos

Nubars papers and the Armenian question, : documents (Waltham, MA, ), doc. ,

AA (hereafter, Boghos Nubar papers).

A N D R E KO S VA R N AVA

commander-in-chief of the British forces in Egypt, Lord Kitchener, the war

secretary, and Winston Churchill, the rst lord of the Admiralty. But there were

complications, such as the French demanding a role in a landing, and the

unsuccessful attempt to force the Dardanelles with the navy alone on March

. The original plan was to land troops at Alexandretta regardless of

whether the forcing of the Dardanelles by the navy had succeeded or failed.

But this plan was overlooked for landing troops at Gallipoli, upon the advice of

the naval and army high command in charge of forcing the Dardanelles.

In any event, the British government had rejected the formation of a Lgion of

Armenian volunteers on March for various reasons, including: the uncertainty over the Alexandretta landing; that they were cold about forming such

Lgions, having also rejected in Cypriot and Jewish Legion proposals;

and as shown below, the British considered that the proposal would result in the

killing of non-combatant Armenians, before and after the Genocide.

On the day ( April) that the Ottoman government arrested leading

Armenian elites in Constantinople, the day that Armenians commemorate

the Armenian Genocide, Cecil Spring-Rice, the British ambassador to

Washington, informed Sir Edward Grey, the British foreign secretary, that

George Bakhmeteff, the Russian ambassador to Washington had told him that

the Armenian National Defence Committee were offering to send , men

via Canada to ght in operations in Cilicia and would pay for uniforms and

passage to a Canadian port. The War Ofce would not entertain this or any

other scheme and Spring-Rice was accordingly informed. The Foreign Ofce

was equally opposed. In a minute on April, Harold Eustace Satow opined:

I dont know what value from a military point of view an Armenian rising in

Cilicia would have, but I feel little doubt that it would lead to the massacre of a

large number of innocent Armenians. Little, of course, did he know what had

transpired four days earlier.

Churchill to Kitchener, Jan. , London, BL, Curzon papers, F/; George H.

Cassar, The French and the Dardanelles: a study of failure in the conduct of war (London, ),

pp. ; and George H. Cassar, Kitcheners war (Dulles, VA, ), p. .

Cassar, The French and the Dardanelles, pp. ; Les A. Carlyon, Gallipoli (New York, NY,

), pp. .

Secretary to Army Council to under-secretary at FO, Mar. , TNA, FO//

.

See les TNA, Colonial Ofce (British) (CO) //, CO//,

CO//, CO//, CO//, and CO//.

Watts, The Jewish Lgion and the First World War, pp. and ; see also Matityahu

Mintz, Pinhas Rutenberg and the establishment of the Jewish Lgion of , Studies in

Zionism, (), pp. ; Yanky Fachler, The Zion Mule Corps and its Irish commander,

History Ireland, (), pp. .

Decipher of telegram from Sir C. Spring-Rice, Washington, to FO, Apr. , TNA,

FO//, p. .

Under-secretary at WO to under-secretary at FO, Apr. , TNA, FO//

; FO telegram to Sir C. Spring-Rice, Apr. , TNA, FO///.

Minute, Harold Eustace Satow, Apr. , TNA, FO//.

F O R M I N G T H E L G I O N DO R I E N T

In any event, Grey informed the Colonial Ofce, which was being included in

the discussion because the scheme involved training the Armenians on Cyprus,

that he rejected it because the Army Council have repeatedly expressed the

view that half organised volunteer risings of this description would have little

military value and that they should not be encouraged. There is also little doubt

that such an expedition . . . would result in the massacre of many innocent

Armenians.

Despite the Army Council rejecting the Armenian scheme to raise a

contingent, various quarters pushed for one after the Ottoman extermination

policy. In July , the Armenian Committee of National Defence addressed a

letter to General Maxwell in Egypt, calling on British military action on the

Cilician coast in order to stop the massacres against the Armenians and that

there were Armenian volunteers in Egypt willing to participate. About a week

later, the Committee of Armenian National Defence reiterated their appeal to

Maxwell, disclosing that a volunteer movement under their direction was

developing in America and elsewhere. The committee recognized that it was

useless for the Entente to now land at Cilicia as previously suggested, but it could

not remain idle as reports of massacres continued to pour in. Modifying their

earlier proposal, the committee now wanted to concentrate a force in Cyprus

and make landings at Mersina and, if strong enough, at Beilan. If successful,

these actions could paralyse Ottoman movements in Asia Minor. Once they had

disembarked a large force from Cyprus they would have no difculty in holding

the Taurus, Anti-Taurus and Amanus Mountains against the Turks, especially

now that the latter are fully occupied with the Russians on the Caucasus and the

Anglo-French in Gallipoli. The committee was certain of , men now in

Russia, Greece, Armenia, Bulgaria, and America, and all that it wanted was for

British ofcers to train them on Cyprus.

British ofcials in Egypt continued to show interest. Lieutenant-Colonel

Sir Arthur Henry McMahon, the high commissioner in Egypt since January

, sent Lieutenant-Colonel Mark Sykes, a Conservative MP and a long time

traveller to the Ottoman Empire, to consult with Armenian representatives

in Cairo. There, on August, he discussed the proposal with Vahan Malezian, a

Cairo attorney and secretary to Boghos Nubar, and Mihran Damadian, a

Hunchak and a leader of the Sassoun rebellion of . Sykes informed

Maxwell of the plan, which called for the raising of , Armenians, , of

whom had fought in the Bulgarian and Ottoman armies, and the rest workers in

the US, who would be trained on Cyprus to land on the northern Syrian coast,

landing about men to seize Suedieh and create disorder in the vicinity,

FO to CO, May , TNA, CO//, /.

McMahon to Grey, July , incl., enclosures signed by T. Moutafoff and

A. Gamsaragan, TNA, FO//, p. .

McMahon to Grey, July , TNA, FO//, p. ; notes on military

operation at Cilicia by the Committee of Armenian National Defence, July , TNA,

FO//.

A N D R E KO S VA R N AVA

with the rest forming bands of about fty and landing at various points between

Ayas and Piyas, pushing north towards Zeitun and Albistan, and there operate as

comitajis (irregular ghting units) along Macedonian lines. From approval of

the scheme, the force would be operational in eight weeks, so if approved on

August, operations would commence on October, allowing the force to

enter the mountains before the snow began. The Armenians only needed from

the Allies arms, munitions, transport, and cover for their landing. Sykes opined

that the concentration of such a force on Cyprus would be protable even if

held in reserve, causing the enemy uneasiness as regards a vulnerable point,

and might be useful as a feint to conceal other operations. Sykes added that it

would be better to give the Armenians something to do rather than have them

become restless and perhaps divided. Also, the French would need to approve

and could provide their contingent at the Dardanelles as an army of occupation

of the Adana Vilayet if the scheme succeeded.

The Russians, desirous of having another front in Anatolia or Syria to relieve

pressures in Transcaucasia, pushed the British with a similar scheme put

forward by Captain A. H. Torcom, a Bulgarian Armenian serving in the Russian

army. Torcom visited George Buchanan, the British ambassador extraordinary

and plenipotentiary at Petrograd, leaving with him his scheme for the

organization of Armenian volunteers for service against the Ottoman Empire.

Torcom claimed that he could recruit , men into ten battalions, and

perhaps even , men into thirty battalions, through recruiting centres at

Alexandria, Marseilles, Liverpool, and New York. The corps would be concentrated at Egypt and under the command of either the French or the British.

Buchanan told Torcom that he sympathized with the scheme and its cause, but

believed it would be hard to gather the volunteers and provide them with

arms.

Despite Russian encouragement, the Ottoman extermination policy, and the

military benets outlined by the Armenian committee in Cairo and Torcom,

the War Ofce stood rm in rejecting the schemes, a decision the Foreign

Ofce supported. Harold Nicolson at the Foreign Ofce minuted that

the scheme proposed by the Committee is not over ambitious and might be

successful, if only in creating a diversion . . . [but] the difculty is that the Turks

would immediately take reprisals on the Armenians actually in their power, and

massacres would immediately follow in Constantinople and elsewhere.

Sykes to Maxwell, Aug. , TNA, FO//.

Torcom, Aug. , TNA, FO//; Buchanan to Grey, Aug. ,

incl. Torcom outline of Armenian Corps, Aug. , TNA, FO//, p. .

Langley to Army Council, Aug. , TNA, FO//; FO to Findlay,

July , TNA, FO//; WO to FO, Aug. , TNA, FO//

// (M...); FO to DMO, Aug. , TNA, FO//.

Minute, Harold Nicolson, Aug. , TNA, FO//.

F O R M I N G T H E L G I O N DO R I E N T

As for Torcoms proposal, the Army Council thought it more practical than

any of the others previously submitted, but the results likely to be achieved . . .

are not such . . . to justify His Majestys Government in supporting the scheme in

view of the difculties that its adoption would entail, and of the Financial

responsibilities in which it would involve this country.

The War and Foreign Ofces had a number of reasons to oppose the

formation of an Armenian Lgion. In a reverse-type of humanitarianism, their

approach to preventing massacres was not to provoke the Ottomans or to

embark upon a humanitarian intervention in response to predicted massacres

of allies in the event of a landing. This takes further the cases explored by

Rodogno across the century before the Great War started, where he shows how

humanitarian intervention required both a favourable European political

climate and one or more European powers believing that their interests, usually

imperial, were at threat before intervening. Ultimately, this was a weak

position, alongside the Armenian approach, which was to defend themselves

against the inevitable through the formation of an Armenian Lgion. In weighing up the idea, the British also determined that the investment in nance,

materials, and training did not justify the potential results. These potential

results must be understood in two ways: defeating the Ottoman Empire and in

post-war spoils (i.e. imperialism). Both British and German military personnel

wrote after the war, so with the benet of hindsight, that they were bewildered

that the British and French had not attacked Alexandretta in because the

area was an Ottoman point of weakness in so many ways, while British

intelligence in the area was certainly aware of this. What was missing from the

equation was the additional gains war spoils and therefore imperialism and

these had not been considered let alone determined, while the area was as

much a French interest as it was of British interest.

III

The British rejection of an Armenian Lgion was further reected in the British

and French rejection of General Maxwells plan to use the able-bodied Musa

Dagh survivors to launch raids on Alexandretta, and in the subsequent French

rejection of a French Armenian Lgion.

The story of the Musa Dagh refugees, made famous in Franz Werfels

epic tale, warrants a separate article, yet for the purposes of this article it is

necessary to establish how the refugees played an important part in why the

French were approached to form the Lgion in and rejected it, and the

WO to FO, Sept. , TNA, FO//// (M...).

See various cases in Rodogno, Against massacre.

Lieutenant-General Sir Gerald Ellison, deputy quartermaster general during the Gallipoli

campaign, and Paul von Hindenburg, chief of the German General Staff.

See Varnava, Imperialism rst, the war second; and Andrekos Varnava, British military

intelligence in Cyprus during the Great War, War in History, (), pp. .

A N D R E KO S VA R N AVA

subsequent decision to establish the Lgion dOrient almost a year after in

October .

Starting in July , Musa Dagh (Moses Mountain) was the site of an

Armenian resistance to Ottoman extermination efforts. The inhabitants of the

region, issued with deportation orders, f led to the mountain where they prepared a camp and defensive lines, and successfully thwarted several Ottoman

assaults for fty-three days. Just when defence was becoming impossible, they

communicated with French warships patrolling the Syrian coast, which transported them to Port Said.

The British authorities did not want the responsibility of looking after the

Musa Dagh refugees and neither they nor the French knew what to do with

them, until almost a year later when the men t for military service formed the

nucleus of the Lgion dOrient. On September , John Clauson, the

high commissioner of Cyprus, telegraphed Andrew Bonar Law, the colonial

secretary, that three days earlier Louis Dartige du Fournet, the French admiral

on the Syrian coast, telegraphed him that , Armenians were bravely

ghting the Ottomans at Musa Dagh. The admiral, replying to a distress signal,

provided them with munitions and provisions, but the Armenians wanted the

safe removal of about , women, children, and elderly to Cyprus. Fournet

needed a reply by September when he would head for Port Said. Yet,

Clauson waited three days before sending his reply to London, a reply that also

reached the French Foreign Ministry on that day, in which he bluntly wanted

the admiral informed that

I greatly regret that in view of the very limited accommodation in Cyprus which has

already hypothecated for other refugees it is quite impossible to receive them. I may

add that the introduction of victims of insurrectionary ghting amongst this partly

Turkish and partly Christian population is politically inadvisable.

Both of Clausons points were misplaced. The eventual introduction of

the Lgion into the ChristianMuslim mix of Cyprus did not see Christians

(Cypriots and Armenians) teaming-up against Muslims, instead exposed a

peasant and labouring class still emerging out of a pre-modern Ottoman millet

tradition with an identity based on religious afliation, the village, and opposition to outsiders (in this case Armenians), rather than ethnic or

For the dramatization, see the famous novel by Franz Werfel, The forty days of Musa Dagh,

intro. Peter Sourian (New York, NY, , rst published in German, ).

See Sourian intro. to novel in ibid.

Telegram, Clauson to Bonar Law, Sept. , TNA, CO//; telegram by

McMahon to FO, Sept. , TNA, FO //; various, pp. , FFMA, , I;

see also Le captitaine de vaisseau Chamonard, Chef dtat-major de la Escadre de la

Mediterranee to Lieutenant-Colonel Elgood, Port Said, Sept. , Cambon to Delcass,

Sept. , Bertie to Foreign Ministry (French) (FM), immediate, Sept. , Le contreadmiral Darrieus, Commandant la Division et p. I. Escarde de la Mediterranee to Elgood,

Sept. , Bertie to FM, immediate, Sept. , and various other documents, in Arthur

Beylerian, ed., Les grandes puissances, lEmpire Ottoman et les Armniens dans les archives franaises

() (Paris, ), pp. .

F O R M I N G T H E L G I O N DO R I E N T

racial factors. Clausons other claim that the Armenians ghting at Musa

Dagh were part of an insurrection, that is, part of one of the Armenian

revolutionary groups that had now revolted, was also wrong. The Musa Dagh

Armenians were resisting deportation, and doing a good job of ghting the

mutual Ottoman enemy.

General Maxwell believed this, writing to Kitchener that

everything should be done, I think, to help the movement, and, with either Cyprus

or Rhodes taking their women and children, it will make an important diversion

from the Dardanelles if we can promote the Armenian movement. I think it is

advisable to exercise a little pressure in Cyprus.

Maxwell was bored with his role of providing training and supplies to troops

destined for Gallipoli and Salonika (his transfer request was honoured in March

, whereupon he was posted to Ireland and notoriously put down the Easter

Rebellion), so action closer to Egypt excited him. The War Ofce, not understanding the urgency of the situation, wanted more information because it

disbelieved the number of Armenians holding off the Ottoman forces.

With no answer on September, Paul Cambon, the French ambassador

to London, informed the Foreign Ofce that the admiral wanted to transport

the refugees to Cyprus or Egypt, while on the same day Maxwell informed

the War Ofce that the French admiral had already loaded the ,

refugees onto cruisers and that they should be taken to Cyprus or Rhodes.

See Varnava, British imperialism in Cyprus, pp. ; for an exploration of the Cypriot

political-religious elite and their gradual move away from co-operation with the Ottomans and

British to hostility, see Michalis N. Michael, Panaretos, : his struggle for absolute

power during the era of Ottoman administrative reforms, in Andrekos Varnava and Michalis N.

Michael, eds., The archbishops of Cyprus in the modern age: the changing role of the ArchbishopEthnarch, their identities and politics (Newcastle upon Tyne, ), pp. ; Kyprianos D. Louis,

Makarios I, : the Tanzimat and the role of the Archbishop-Ethnarch, in ibid.,

pp. ; Andrekos Varnava, Sophronios III, : the last of the old and the rst of

the new Archbishop-Ethnarchs?, in ibid., pp. ; Andrekos Varnava and Irene

Pophaides, Kyrillos II, : the rst Greek nationalist and Enosist ArchbishopEthnarch, in ibid., pp. ; for an understanding of how Europeans and educated Cypriots

established a provincial high society and exploited the peasantry and working classes, see

Rolandos Katsiaounis, Labour, society and politics in Cyprus (Nicosia, ); and Marc Aymes,

The port-city in the elds: investigating an improper urbanity in mid-nineteenth-century

Cyprus, Mediterranean Historical Review, (), pp. ; for an introduction into Cypriot

society at the time of the Great War, the importance of the Cypriot Mule Corps and the impact

of the Armenian Lgion, see Andrekos Varnava, Famagusta during the Great War: from

backwater to bustling, Michael Walsh and Tamas Kiss, eds., Famagusta: city of empires (

) (Newcastle upon Tyne, forthcoming ).

Bloxham, The great game of genocide, p. .

Secret, Maxwell to Kitchener, Sept. , TNA, FO//; Secret,

Maxwell to Kitchener, Sept. , TNA, CO//.

Secret, WO to GOC Egypt, Sept. , TNA, FO// (also in CO/

/).

French admiral, Sept. , TNA, FO//; GOC Egypt to WO, Sept.

, TNA, FO// (also in CO//).

A N D R E KO S VA R N AVA

On September, the Foreign Ofce debated where the , Armenian

refugees should be taken, one minute stating that pressure should be exerted

on Cyprus; then Grey minuted that both Cyprus and Egypt were out of the

question. Finally, on September, the Foreign Ofce informed Baron Bertie

of Thame, the British ambassador to Paris, that the importation of victims of

insurrectionary ghting between Turks and Christians would in present state of

feeling in both Cyprus and Egypt be wholly undesirable, and that the French

should arrange to take them to Rhodes or Algeria. In other words, the French

should deal with them in Algeria, or the Italians in Rhodes. In the event,

the French admiral, no doubt desirous of getting back to his work and relieving

the refugees, disembarked them at Port Said, much to the annoyance of the

Egyptian authorities, who insisted to London that this could only be temporary. Clearly, the French political and military authorities were in a weak

position alongside their British allies, so much so that they attempted to accommodate the British position to relocate the refugees. They tried and failed to

have them accepted in Rhodes, Algeria, Tunis, Morocco, and by the Russians in

the Caucasus. This not only reects the power of allies to inuence policies,

but also of local bureaucratic elites on the periphery to do so as well, even

against their own central state authorities.

While the British pushed the French to relocate the Armenians elsewhere

and to take complete responsibility for them, General Maxwell proposed

forming them into a ghting unit to raid the Syrian and Cilician coasts. On

September, a week after they had been dumped at Port Said, the French

minister in Cairo (since ), Jules-Albert Defrance, informed Paris that a

leader of the Musa Dagh resistance, Pierre (or Peter) Dimlekian, informed him

that those in a condition to bear arms numbered and were aged between

fteen and sixty, and about of these would make good soldiers. Defrance

informed his superiors that Maxwell had proposed forming an Armenian

Lgion, which could raid Ottoman coasts in the Alexandretta region, but

Dimlekian preferred to ght with the French. Paris wanted more information

about Maxwells plan and the refugees, so Defrance visited the camp on

September, where the Armenians were under British quarantine, and

informed Paris that there were , in total: men, , women, boys,

girls, and infants. He conrmed that men were t to ght and

Nicolson minute, Sept. , and Grey minute, Sept. , TNA, FO//

FO to Bertie, Sept. , TNA, CO//, .

.

McMahon to FO, Sept. , TNA, FO//; Darrieu report, Sept.

, pp. , FFMA, , I.

Algeria, Sept. , p. , Russians, Sept. , p. , Russians, Sept. ,

p. , Tunis, Sept. , p. , Morocco, Sept. , Russians, Sept. , p. ,

Algeria, Oct. , p. , FFMA, , I.

For an example of how this happened in Cyprus, between John Clauson, the high

commissioner, and the authorities in London, see Varnava, British imperialism in Cyprus,

pp. , and Varnava, British military intelligence in Cyprus during the Great War.

FFMA, , I, Defrance to Paris, Sept. , p. .

F O R M I N G T H E L G I O N DO R I E N T

to work. The Armenians told Defrance that they had resisted the Ottomans

for over forty days and wanted to continue ghting the Turks. Defrance

informed Paris that Maxwell had spoken to Dimlekian about the British using

the Armenians to raid Alexandretta and that Defrance had told Dimlekian that

the French and British were co-operating on this because the French were not

competing with the British.

Although Maxwell was interested in using the Musa Dagh Armenians to form

a Lgion, he was not interested in those that could not ght. Defrance and

Maxwell proposed to their respective governments that the French would cover

the expenses of the Armenian refugees and an Armenian Lgion should be

formed to launch raids on the Syrian and Cilician coasts. Soon, the various

opinions on the formation of an Armenian Lgion manifested. Lieutenant de

Saint Quentin in Cairo opined that a raid by Armenians in the Alexandretta

region would attract the Ottomans to the region and should therefore not be

attempted so long as the French and British still had designs on the region.

A member of the Foreign Ministry suggested forming a committee of

Armenians to appeal for support from the Armenian diaspora, notably in the

US, but the bottom line was that, like the British government, the French did

not want to encourage a rebellion which did not have good prospects of success.

Ultimately, however, both governments would decide together. Maxwell

pushed for a decision because he wanted the refugees to leave as he worried

they would become frustrated if they remained idle. Grey informed his

French counterpart that the French were responsible for nding work for the

refugees, and suggested work on the Gallipoli beaches. Thophile Delcass,

in one of his last acts as foreign minister, informed Cairo that he had agreed

with Grey that the Armenian refugees should be sent as labourers to Mudros.

Indeed a French military agent in Egypt attempted to recruit from the Musa

Dagh refugees for service at Gallipoli and Mudros.

Yet the voices supporting the formation of the Musa Dagh refugees into a

combat unit were numerous. Arshag Hovhannes Tsobanian (or Chobanian), an

Ottoman Armenian in Paris, and a famous writer, journalist, and editor,

suggested to the Foreign Ministry that the refugees be formed into combat

units, especially since, in his view, the Armenian struggle in Cilicia and the

surrounding mountains was not lost. Indeed, Defrance informed Paris that

Perhaps this is where Werfel got the idea of the forty days, since it was actually fty-three.

Three letters, Defrance to FM, Sept. , pp. , FFMA, , I.

Ibid., Defrance to FM, Sept. , p. .

Ibid., Defrance to FM, Sept. , p. .

Ibid., Defrance to FM, Sept. , p. .

Ibid., French military, Defrance, to FM, Oct. , p. .

Ibid., Bertie, undated, pp. .

Ibid., Paris to FM, Oct. .

Lord Bertie to FO, Oct. , TNA, FO//, pp. .

Tsobanian to Paris, Sept. , p. , FFMA, , I.

A N D R E KO S VA R N AVA

the Musa Dagh leaders did not want to work as labourers and they should not be

treated like Ottoman prisoners or like Somalis employed at Mudros. Then,

Vice-Admiral Gabriel Darrieus, the new commander of the rd Squadron on

the Syrian coast, weighed in, informing Paris that the Armenian refugees

wanted revenge on the Turks, not to work as labourers. He favoured using them

as combatants in their native region, particularly in a raid to cut Ottoman rail

communications.

But the voices of opposition weighed more heavily. The French Foreign

Ministry and Defrance in Cairo thought establishing an Armenian Lgion and

using it to raid the Alexandretta area would be a bad idea and it was best to

employ them at Mudros. Captain E. De Jonquires of the French navy, agreed,

rejecting an Armenian corps of irregular troops because this might provoke the

Turks, and although the Armenians may not like it, they should be pushed to

work as labourers at Mudros. Cambon reported that the British and he were

sceptical about encouraging an Armenian uprising in Cilicia because of

Ottoman reprisals and were coming around to the idea of employing them at

Mudros, well away from Egypt where they might cause mischief. The French

War Ministry agreed, although worried about using the Armenians as labourers

because of their lack of aptitude, the naval authorities were opposed to

forming them into a ghting unit. The new French foreign minister and

prime minister, Aristide Briand, agreed with the reservations over forming an

Armenian Lgion, which were also shared by Defrance, because it would merely

provoke further Turkish massacres.

Ofcially, however, it seems that the French authorities in Cairo were not

informed of this decision. In December , Defrance messaged Paris that the

male Armenian refugees wanted to return to their mountains after being

trained and armed and that if the government approved the French authorities

in Egypt would arrange this.

IV

One of the reasons given for rejecting an Armenian Lgion in was that it

would incite the Ottomans to implement more massacres, but this reason was

overcome in January . In a letter to the French military authorities in

Egypt, the War Ministry instructed it to proceed with forming an Armenian

Lgion. Then, in a letter to members of the Armenian Defence Committee in

Ibid., Defrance to Paris, Oct. .

Ibid., Darrieus to Paris, Nov. , pp. .

Note to FO, Oct. , p. , FFMA, , I.

Jonquires to Paris, Nov. , pp. , FFMA, , I.

Ibid., FM to Defrance, Nov. , p. .

Ibid., War Ministry (French) (WM) to FM, Nov. , p. .

Ibid., Nov. , p. .

Defrance to FM, Dec. , p. , FFMA, , I.

WM to French military, Cairo, Jan. , FFMA, , I.

F O R M I N G T H E L G I O N DO R I E N T

Cairo, the British and French military representatives in Egypt agreed to form a

Lgion only if they would not be held responsible for more Ottoman massacres.

The number of Armenians likely to serve is so small as to be at the present time of no

interest to the Allied Powers; the only object of their employment is to give to the

Armenians some material claim to their reinstatement in their original country; it is

therefore a matter of purely Armenian interest . . . [Therefore], the Allied

Governments are free of any moral responsibility for reprisals or acts of violence

on the part of the Turks that may be regarded as reprisals for the employment of

these volunteers.

Based on this extraordinary condition, the Armenian committee was told that

the Allied Governments are prepared to form a Volunteer force from the

Armenian refugees of Djebal Moussa and from such other Armenian

Volunteers as may be sent in by the Committee.

The deal the Armenian National Committee was being asked to accept was

unbalanced. The Allied governments would administer military training; provide arms, ammunition, accoutrements, and boots; and employ the volunteers

only in the districts of Cilicia and Lesser Armenia with which the Armenians

are as natives familiar. On the other hand, the Armenian committee was

responsible for proving each volunteer with a ration allowance and pay totalling

PT (Egyptian Piastres) per diem; six trained men as sous-ofcers, funded by

the committee; extra pay of PT a day for volunteers given responsible positions; and material for clothing since not all the volunteers would wear

uniforms. It is obvious from both the tone and the content of the letter that the

French government had approved the detailed and specic proposals.

Despite this change of heart, this time it was the Armenians who rejected the

formation of a Lgion. Defrance informed Paris that the matter of forming an

Armenian force was in doubt because the Armenian National Defence

Committee believed that activities by such a force would provoke dangerous

Turkish reprisals. The Hunchak party, however, was pressing the French naval

commander to hasten the arming of Armenians, but Vice-Admiral Moreau,

commander of the rd Squadron, opposed using the Musa Dagh refugees in

this way. Defrance, however, believed that the option should be open. The

strongest opposition came from the most inuential Armenian, Boghos Nubar.

In a letter to Moreau on March, he conrmed his position rst taken on

March that he opposed any Armenian action that could lead to retaliations

on Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, including the formation of a volunteer

Lgion. He argued that if Armenians wanted to ght, they should enlist with

one of the Allies. In Nubars letter, which Defrance sent to Briand, he

Ibid., British MIO, Cairo, to Armenian committee members, Feb. , pp. .

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid., Defrance to Paris, Feb. , pp. .

Boghos Nubar to Admiral Moreau, Port Said, Mar. , p. , FFMA, , II, Turkey,

Jan. to Mar. .

A N D R E KO S VA R N AVA

expressed concern over the British training about Musa Dagh Armenians in

order to blow up railway bridges in Alexandretta and was relieved that the idea

was abandoned after the Armenian bishop in Cairo and the Eastern Orthodox

patriarch of Alexandria objected for fear of Ottoman reprisals. The concerns

over retaliations must be understood within the context of the Genocide and its

progress, since it implies that there were still some Armenians in the Ottoman

Empire that had escaped it, but unlike six months earlier these Armenians were

isolated and not in a position to be protected by an Entente landing with an

Armenian contribution.

Nubars rejection carried much weight, despite the obvious power imbalance

alongside the French and British. Indeed, Defrance believed that the question

of raising an Armenian Lgion was nally closed. Then, seemingly, the nal

nail in the cofn came from the French War Ministry, which announced that

French law forbade the enlistment of enemy nationals into the French army.

V

It was not, however, the nal nail in the cofn. The proposal was resurrected

and agreed to in August by the commander-in-chief of the French army

and the French government and ofcially agreed to by all parties concerned in

October.

On June , the British Foreign Ofce informed its French counterpart

that it had received a request to free Armenian prisoners of war held in India

and wanted to know whether the French had any plans to use the Armenians in

any way related to the war. Then, on July, Cambon informed the Foreign

Ministry that an idea was being examined to form an Armenian corps on

Cyprus, at French expense, since a recent agreement ceded large parts of

Armenia to France. Here lies the reason for the resurrection of the proposal

to form an Armenian Lgion, but before exploring this further it is important to

complete the story. Over two weeks followed before Cambon updated the

Foreign Ministry that Brigadier-General Gilbert Clayton, of the Arab Bureau in

Cairo, in discussions with Georges-Picot, suggested that the Armenian refugees

in Egypt and those imprisoned in India could be made into soldiers and

grouped on Cyprus to dissuade the Ottomans from moving all their troops

southwards against the sherif of Mecca. The British suggested that the

Armenians be trained and armed by French ofcers, which Cambon thought

would show French strength without enlarging their eld of operations and

control the Armenian partisans who might seek to create principalities in

Ibid., Defrance to Briand, Apr. , p. , including Nubar letter, Mar. , p. .

Ibid., Defrance to Briand, Mar. , p. .

WM to Cairo, May , p. , and WM to Cairo, May , p. , FFMA, , I.

Ibid., FO to FM, June , p. ; also commander-in-chief French armies to FM,

Ibid., Cambon to FM, July , p. .

July , p. .

F O R M I N G T H E L G I O N DO R I E N T

northern Syria. Also, it offered a solution as to what to do with the Musa Dagh

refugees, who refused to take jobs or act as auxiliaries.

The resurrection of the idea to form an Armenian Lgion was largely due to

the SykesPicot Agreement. This was what Cambon meant when he mentioned

the cession of Armenian populated territories to France in a recent agreement.

When the Gallipoli expedition failed, resulting in Bulgaria joining the Central

Powers, and when the British offer of Cyprus to Greece, in order for that

country to aid Serbia immediately, also failed, the British and the French (and

indeed the Russians) needed to work together more closely. Consequently, they

decided that they needed to focus on what their aims were in defeating the

Ottoman Empire, and given Russian ambitions on Constantinople and

Transcaucasia (reected in a separate agreement with the Russian foreign

minister, Sergei Sazonov), French interests in Syria and Cilicia, and British

interests in Egypt and Mesopotamia, it became obvious that the military effort

needed to concentrate on where the British and French interests were. These

interests were captured in the SykesPicot Agreement, negotiated and signed by

Franois Georges-Picot for the French and Mark Sykes for the British on May

. Sazonov played an important role in the agreement, since it was he who

proposed to Picot that France obtain a share of Ottoman Armenia (i.e. Cilicia),

which pleased Picot, who was in the highest spirits over his new Castle in

Armenia. The SykesPicot Agreement divided the Ottoman vilayets from

Adana to Basra into either direct or indirect (where an Arab state would be

created) spheres of French or British control. Cilicia (mostly in the Adana

vilayet) and neighbouring Ottoman vilayets with a substantial Armenian population would come under direct French control; with the other vilayets populated by Armenians coming under Russian protection. British and French

imperial rivalry was suddenly reinvented and a new collaborative relationship

was formed, linking the successful prosecution of the war with post-war imperial

expansion.

Once French and British post-war imperial expansion was settled upon, it

did not take long for them to embark upon a determined effort to form an

Armenian Lgion. On August the commander-in-chief of the French army,

General Joseph Joffre, accepted the proposal to form an Armenian Lgion.

Joffre agreed with General Pierre Roques, the minister of war, a close friend

from their days at the cole Polytechnique in the s, that forming an

Armenian Lgion on Cyprus was an opportunity to threaten the Ottomans and

allow the Allies to support a revolt against the Ottomans if desirable. If the

Ibid., Cambon to FM, July , pp. .

Varnava, British imperialism in Cyprus, pp. .

Christopher M. Andrew and A. S. Kanya-Forstner, France overseas: the Great War and the

climax of French Imperial expansion (London, ), p. .

See le, TNA, FO//.

Joffre, commander-in-chief army, to Roques, Aug. , sent to FM on same day,

pp. , FFMA, , I.

A N D R E KO S VA R N AVA

Bosnian battalion at Salonika was an example, thirty ofcers would sufce,

opined Joffre. Joffre wanted the Armenian corps to be ready to exploit any

political situation in order to cause the Ottoman Empire insurmountable

difculties in this region, and so he wanted the Lgion to be under a

commander who was responsible to the rear-admiral commanding the Naval

Division of Syria. He wanted an Armenian revolt and would direct the rearadmiral to supply them with arms, because ultimately it was in the interests of

the Allies to keep Ottoman forces dispersed and engaged in Asia.

The Foreign Ministry was anxious for the War Ministry to decide, and the

afrmative decision from Roques came on August. He told President

Raymond Poincar and Briand that he would be willing to supply personnel,

arms, and provisions for an Armenian Lgion on Cyprus, which could act either

as partisans or as one of several foreign battalions, constituted like the Bosnian

battalion in regular units, receiving the same supplies as French troops. The

second option would best maximize the investment and was therefore more

economical, as Joffre indicated. Roques wanted to know if the British had

agreed and was worried that there were not enough Musa Dagh refugees (on

May he was informed no more than ) and their mediocre value had led

the War and Naval Ministries to reject using them. He assumed, therefore, that

the units formed would be drawn from the Armenian population in Egypt

and India, and from the scattered individuals assembled from Asia Minor and

Syria in various places. Roques wanted French ofcers sent to ascertain the

conditions in which the rst units would be created, with the head of this

mission becoming the commander of the corps. He would have to reach an

understanding with local British authorities, and with the rear-admiral

commanding the French naval division, and then would have to submit to

Roques his proposals for organizing the corps. If this was agreeable to the navy,

the British, and Poincare and Briand, Roques would immediately send this

mission to Cyprus.

Four days later, the French Foreign Ministry informed Cambon that the War

Ministry was ready to send a mission to Cyprus to organize an Armenian corps,

following the suggestion of Brigadier-General Clayton, and wanted Cambon to

ask Whitehall if it agreed and if so to inform the French on how many t

Armenians there were in Egypt and India who could join. Cambon informed

Grey but did not mention if the Lgion would be trained by the British, the

French, or both, putting it forward as a joint Anglo-French idea. Sykess

minute was most revealing. He backed the scheme because it was a necessary

Ibid.

Ibid., FM to WM, Aug. , pp. .

Ibid., Roques to Briand, Aug. , pp. .

Ibid., Roques to Briand, Aug. , p. .

Ibid., FM to Cambon, Aug. , p. .

French ambassador, London, to FO, Aug. , TNA, FO//; FO to

CO, Aug. , TNA, CO//, w//; Cambon to FO, Aug. ,

TNA, CO//.

F O R M I N G T H E L G I O N DO R I E N T

corollary of the SykesPicot agreement and because it would propel AngloFrench military co-operation in the Levant. Cambon did not ask if the British

agreed to the Lgion; instead, he asked how many militarily t Armenians the

British held. The War Ofce informed Grey that there were in Egypt

(Musa Dagh refugees) and another prisoners of war in India, but how many

were t for combat and would consent to ght was unknown. The prisoners at

Sumerpur, India, the India Ofce opined, would do well, having been taken

from the Ottoman army in Mesopotamia. As for the Musa Dagh refugees in

Egypt, the director of military intelligence, Major-General Macdonogh, believed

that few had martial qualities, while he claimed that Brigadier-General Clayton

was against the idea because they were not of good ghting material,

contradicting French views of Claytons position. A labour company was formed

in Egypt from amongst the refugees for work on the defences of the canal, while

Maxwell was considering using them as muleteers in Salonika to augment the

Macedonian (Cypriot) Mule Corps. In any event, Sir Ronald Graham, of the

Ministry of the Interior in Cairo, revealed that there were about capable

men at the Armenian refugee camp, but that he had failed to induce any to

volunteer for the Macedonian Mule Corp or for a labour camp, and felt that

compulsion might be needed.

The Foreign Ofce replied to Cambon without stating that the British

government had accepted or rejected the proposed scheme, although it

implied that it had accepted it because it only encouraged it. The letter

disclosed how many Armenians were under British authority and that Clauson

had been requested to provide information on a camp.

The initial Colonial Ofce view was neither negative nor positive. There was,

a minute stated, no reason why such a body should not be sent to Cyprus were it

not that it might have very bad political results on the Moslem population of the

Island who do not like Armenians. This was a gross generalization. The

Colonial Ofce decided to wait for Clausons views before ofcially giving its

own. Clauson was a notoriously stubborn high commissioner: in October

Sykes minute, Aug. , TNA, FO//.

WO to under-secretary at FO, Aug. , TNA, FO////

(M. I..); Secret, FO to Cambon, Aug. , TNA, FO//, W./;

Secret, India Ofce to FO, Aug. , FO//, M. ; telegram from

India Ofce secretary to viceroy, June , TNA, FO//, M. ; viceroy

to Lord Bryce, India secretary, June , TNA, FO//, H. ; B. B.

Cubitt, WO, to under-secretary for India, military secretary India Ofce (British) (IO), June

, TNA, FO//// (M. I..).

R. Graham, Ministry of the Interior to McMahon, Sept. , TNA, CO//

, p. .

FO to Cambon, Aug. , TNA, FO//.

Minute, Aug. , TNA, CO//.

Secret, CO, Bonar Law to Clauson, Aug. , TNA, CO//; CO,

Grindle, to FO, Aug. , TNA, CO//; FO to CO, Sept. , TNA,

CO//, w//; Cambon to Grey, Sept. , TNA, CO//

, ; FO to CO, Sept., TNA, CO//, w//; Grey to

A N D R E KO S VA R N AVA

, he had refused to inform the Greek and Turkish Cypriot political elites

that the British government had formally offered to cede the island to Greece

because he did not want to upset the loyal Muslim elites; he had a difcult

relationship with the military intelligence ofcers working on Cyprus and Egypt

because they considered him too negligent on security and he considered the

military intelligence ofcers too intrusive; and nally his rejection of the

Musa Dagh refugees. This time, Clauson was obliging, informing Bonar Law

that there were difculties of sea and land transport and the necessity of

importing many necessities at much expense and delay, and it was advisable to

minimise contact with the Cypriot Turks who are uneasy . . . For these reasons

I would recommend that a secluded site in the north or east of the island be

sought. Bonar Law informed Cambon that he agreed with Clauson on

minimizing contact with the Cypriot Turks.

The military and government authorities in Egypt had mixed views about the

scheme. McMahon, Graham, and General Archibald Murray, commander-inchief of the troops in Egypt, were pleased to be rid of the Musa Dagh refugees

and that the force was not going to be trained in Egypt, but Murray stated

that the British authorities were unable to provide equipment or training, so the

French had to take all responsibility. He was also unhappy with Cypruss

selection as the training base: I do not consider that Cyprus would be a

desirable place in which to train these men but no doubt it will be possible to

nd some other locality which is in French occupation. Graham agreed,

stating that there seems no reason that we should undertake their training

in Cyprus and I imagine that the authorities in Cyprus would not encourage

any idea of the kind. The French now hold several islands in the eastern

Mediterranean, which are equally, or almost equally, suitable for the purpose.

Both Graham and Murray were wrong, as the French wanted Cyprus and

Clauson had agreed, although he had never been asked to agree or disagree

as one Foreign Ofce minute put it, Clauson implied a grudging acceptance.

During September, the French remained apprehensive about the British

position on an Armenian Lgion on Cyprus. On September, Defrance

Cambon, Sept. , TNA, CO//, w./; CO, to FO, Aug. ,

TNA, FO////.

Varnava, British imperialism in Cyprus, pp. .

Varnava, British military intelligence in Cyprus during the Great War.

Paraphrase telegram, Clauson to Bonar Law, Sept. , TNA, FO//

; Grey to Cambon, Sept. , TNA, CO//, w./.

CO to under-secretary at FO, Sept. , TNA, FO//; FO to

Cambon, Sept. , TNA, FO//.

FO to CO, Oct. , TNA, CO//, w//; McMahon to Grey,

Sept. , TNA, CO//, , /; see also FO//.

Murray, commander-in-chief Egyptian Expeditionary Force, to McMahon, Sept.

, TNA, CO//.

Minute, Sept. , TNA, FO//.

F O R M I N G T H E L G I O N DO R I E N T

informed the Foreign Ministry that the French were training about

Armenian refugees in Port Said, but the British preferred to send them to

Salonika as muleteers, although the British merely wanted to be rid of them. He

wanted advice on whether the French government wanted them or not, and if

the French wanted them whether they would pay the cost of keeping them and

their families. Colonel T. G. Hamelin, of the French General Staff second

section Africa, learned that the British were opposed to using Cyprus and so the

French should drop the idea, adding that the Armenians were not worth the

money to compensate the British. But then Defrance sent to Briand two

documents detailing discussions on the ground between French and British

ofcers over what to do with the Musa Dagh refugees that showed that a Lgion

under French command in Cyprus was feasible. In Bremonds letter to

Defrance he detailed the number of Musa Dagh refugees at Port Said, those t

for service, the training already undertaken, and the constructive discussions

with two British ofcers, General Althem and Colonel Elgood, over using the

Armenians. Discussions between Defrance and McMahon showed that the

British had found the Armenians difcult, and would be pleased to be rid of

them.

It was not until September that Cambon informed Briand that the British

did not oppose the creation of an Armenian Lgion, but wanted it camped in

northern or eastern Cyprus where there were fewer Muslims. He also informed

Briand on the number of Armenians under British control (in Egypt and India)

who could form the nucleus of the corps. Although the proposal for a Lgion

was moving towards acceptance, a nal decision had not yet been taken.

Meanwhile, the Musa Dagh refugees were growing restless. The French navy

in the Mediterranean reported to the Naval Ministry that some Musa Dagh

Armenians had protested to the minister of state, Denys Cochin, about being

enrolled in the British army and asking to be employed as paid guides for the

French in their country. The letter, dated September (but not sent to

Briand until October), thanked France for saving them from certain

extermination and declared that they considered themselves under French

protection. They had started military training, but it was stopped without

explanation, and the British offered them work (i.e. as muleteers in Salonika),

which did not match the assurances they were previously given (i.e. that they

would ght the Ottomans on their home soil). They were now told that the

planned operations (i.e. at Alexandretta) could have devastating consequences

for Armenians still in the Ottoman Empire. Yet, they wanted to continue

Defrance to FM, Sept. , p. , FFMA, , I.

Ibid., Hamelin to FM, Sept. , p. .

Ibid., Defrance to Briand, Sept. , p. .

Ibid., Bremond to Defrance, Sept. , p. .

Ibid., Defrance to Bremond, Sept. , pp. .

Ibid., Cambon to FM, Sept. , p. .

Ibid., Admiral Pothuau to Navy Ministry (French) (NM), Sept. , p. .

A N D R E KO S VA R N AVA

training to help France when it needed them to aid in reconquering their

villages and Cilicia. They claimed that the British were threatening to send them

to work on the Port Said roads, and although they have nothing against the

British, they wanted the French to honour the assurance given when they were

saved. Defrance highlighted the restlessness of the Musa Dagh refugees to

the Foreign Ministry on September, asserting that a decision was vital

because of friction with the British. Clearly, the role of local agency again

came to the fore, since the actions (or inaction from a British view point) of the

Musa Dagh refugees in Egypt frustrated the British in Egypt into becoming the

strongest advocates for their formation into the Lgion.

Finally, on September, the ofce of the chief of General Staff, General

Pierre-Georges Duport, informed Briand that London had nally consented to

the formation of a Frenchtrained Armenian corps in northern or eastern

Cyprus (letter received from French Military attach in London dated

September). The problem was that there were only about refugees in

Port Said available and the French vice-admiral had agreed to their

employment as muleteers by the British in Egypt or Salonika. Duport was

sending Commandant Louis Romieu, an infantry ofcer, to Egypt to resolve the

situation with the British. Subsequently, Duport added that the corps may be

recruited from Armenians outside Egypt as well.

The French authorities in Egypt, who were not updated on the latest

developments, observed a change in the British. Saint-Quentin informed the

Foreign Ministry that British authorities were willing to leave employment of the

Armenians to the French, so long as they and their families were removed from

Egypt. Defrance and the French military attach in Egypt informed the

Foreign Ministry that General Murray was fed up with the Armenians because

they had refused to serve as muleteers and had failed as labourers, so he would

be relieved if the French took responsibility for all of them, including their

families. Briand, referring to a further letter by Bremond on the subject,

informed Roques that it was vital to form the Lgion to end British and

Armenian frustration.

In October, the project gathered momentum. On October, Duport

informed Briand that Romieu had left for Egypt to start recruiting and nalize