Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

849273

Transféré par

JASPREETKAUR0410Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

849273

Transféré par

JASPREETKAUR0410Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

Case Reports in Dentistry

Volume 2014, Article ID 849273, 9 pages

http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/849273

Case Report

Esthetic Rehabilitation of Anterior Teeth with

Laminates Composite Veneers

Dino Re,1 Gabriele Augusti,1 Massimo Amato,2 Giancarlo Riva,1 and Davide Augusti1

1

2

Department of Oral Rehabilitation, Istituto Stomatologico Italiano, University of Milan, 20122 Milan, Italy

Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Salerno, 84084 Salerno, Italy

Correspondence should be addressed to Gabriele Augusti; g.augusti@libero.it

Received 21 January 2014; Accepted 20 May 2014; Published 11 June 2014

Academic Editor: Kevin Seymour

Copyright 2014 Dino Re et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

No- or minimal-preparation veneers associated with enamel preservation offer predictable results in esthetic dentistry; indirect

additive anterior composite restorations represent a quick, minimally invasive, inexpensive, and repairable option for a smile

enhancement treatment plan. Current laboratory techniques associated with a strict clinical protocol satisfy patients restorative and

esthetic needs. The case report presented describes minimal invasive treatment of four upper incisors with laminate nanohybrid

resin composite veneers. A step-by-step protocol is proposed for diagnostic evaluation, mock-up fabrication and trial, teeth

preparation and impression, and adhesive cementation. The resolution of initial esthetic issues, patient satisfaction, and nice

integration of indirect restorations confirmed the success of this anterior dentition rehabilitation.

1. Introduction

New ceramic and composite materials have increased conservative treatments of compromised anterior teeth [1, 2].

Indirect additive veneering was introduced in the 1980s as

an alternative to full-coverage crowns. The concept of nopreparation or minimal-preparation [3] has followed the

development of appropriate enamel bonding procedures.

The color and integrity of dental tissue substrates to which

veneers will be bonded are important for clinical success [4];

using additional veneers with a thickness between 0.3 mm

and 0.5 mm, 95% to 100% of enamel volume remains after

preparation and no dentin is exposed [5]. A number of

clinical studies have concluded that bonded laminate veneer

restorations delivered good results over a period of 10 years

and more [68]. The majority of the failures were observed

in the form of fracture or marginal defects of the restoration

[9]. Pure adhesive failures are rarely seen when enamel is

the substrate with shear bond strength values exceeding

the cohesive strength of enamel itself [10, 11]. Some indications for no-preparation veneering include erosion, incisal

edge microfractures, corrections for short and small crowns

(particularly in patients with larger lips), and alterations

in the superficial enamel texture. Restoration of missing

dental tissue with resin composites is quick, minimally

invasive, and inexpensive and the resulting restorations are

easy to repair, if necessary [12]. The present case report

describes the treatment of wear in the anterior dentition

with thin composite laminate veneers, to restore esthetics and

function.

2. Diagnosis and Treatment Planning

A 41-year-old male patient was concerned about his smile;

clinical examination revealed unsatisfactory composite

restorations of upper central incisors, a discrepancy in incisal

marginal levels, and an asymmetry between lateral incisors.

Previous orthodontic treatment did not completely solve the

right lateral incisor rotation (Figure 1).

During the first appointment a complete radiological

and photographic documentation was collected; an alginate

impression was taken for the preliminary wax-up and mockup procedures. Impressions were poured in type IV dental

stone; the models were mounted on a semiadjustable articulator (Figures 2(a) and 2(b)).

Case Reports in Dentistry

Figure 1: Intraoral anterior view of teeth before treatment.

(a)

(b)

Figure 2: (a) Preoperative cast. (b) The same cast with horizontally sectioned silicon index of wax-up.

(a)

(b)

Figure 3: (a) Frontal view of the mock-up made in PMMA resin of teeth 11-12. (b) Occlusal view of the same mock-up.

Figure 4: Intraoral try-in of the mock-up and provisional cementation.

Case Reports in Dentistry

Figure 5: Minimal tooth preparation areas marked on the preoperative cast.

Figure 6: Interproximal preparation using finishing strip.

The preliminary mock-up of teeth 12 and 11 was performed by the technician using bisacrylic resin (Protemp 4,

3M ESPE) to simulate the final result, determining an ideal

width and length teeth ratio (Figures 3(a) and 3(b)).

During a second appointment the preliminary resin

mock-up was tried, checked, and provisionally luted

(Figure 4); any alteration desired by the patient and the

clinician was analyzed, discussed, and adjusted. Static and

dynamic dentofacial aspects were evaluated, considering lip

line and maxillary teeth exposure. The final treatment plan

was approved by the patient after form and function were

confirmed as well.

After all information was obtained by the mock-up, the

technician checked the space available for the veneers and the

path of insertion and highlighted on the dental stone model

the areas requiring clinical preparation (Figure 5). A silicon

index was also provided for the clinician in order to evaluate

the veneers space requirements.

3. Dental Preparation

The least invasive preparation with maximal preservation of

enamel was performed. In order to facilitate the impression

and cementation protocols, interproximal space between

central incisors was at first widened using coarse/medium

finishing strips (each of them has two different abrasive

grades) (Sof-Lex, 3M ESPE); subsequent surface refinement

was performed by fine/superfine strips of the same system

(Figure 6). Medium grit (100 m) and fine grain (30 m)

tapered diamond burs (number 868.314.016 and number

8868.314.016, Kit 4388, Komet Dental, Milan, Italy) were used

to reduce the labial surfaces; clearance for the composite

restoration was checked with the silicon guide.

All the teeth surfaces and past composite restorations

were finished using stone burs (based on a micrograined aluminum oxide grit; Dura-white stones, Shofu Dental GmbH,

Ratingen, Germany) and polishing disks (Sof-Lex Extra Thin

(XT) disks, number 2382SF and number 2382F, 3M ESPE)

to promote maximum impression material adaptation and

adhesive cementation (Figure 7).

4. Chairside Impression

Following the preparations, a small diameter retraction cord

was placed in the bottom of the sulcus to obtain an adequate

gingival displacement (number 00 Ultrapak, Ultradent Inc.).

The cord was left in the sulcus during the entire impression

procedure; this technique limits the flow of crevicular fluid

and provides correct moisture control (Figure 8).

A high quality polyether precision material was used

(Impregum Penta Duosoft, 3M ESPE) to take a one-step,

double mix final impression; a light body (Duosoft L, 3M

ESPE) was applied at the gingival margin and gently blown

over the preparations (Figures 9(a) and 9(b)). A full metallic

tray was loaded with the heavy body impression material

(Duosoft H, 3M ESPE), inserted in the oral cavity, and

allowed to set according to the manufacturers instructions

and then removed (Figure 10).

5. Laboratory Fabrication of Veneers

A working model of the upper arch was obtained by

pouring the definitive elastomeric impression (Figures 11(a)

Case Reports in Dentistry

Figure 7: Refined and polished surfaces before final impression.

Figure 8: Ultrapak retraction cord in situ.

(a)

(b)

Figure 9: (a)-(b) Impregum Duosoft light body material injection.

Figure 10: Detail of the final elastomeric impression.

Case Reports in Dentistry

(a)

(b)

Figure 11: (a)-(b) Buccal and palatal view of the upper ditched master cast.

and 11(b)). The dental technician prepared a wax-up on

the working cast, reproducing all diagnostic information

previously approved by the patient (to accomplish this step,

the clinician recorded and sent to the laboratory an alginate

transfer impression of the mock-up in situ) (Figure 12).

A microhybrid with nanoparticles resin material (Miris 2,

Colt`ene Whaledent) was positioned at the inner surface of

a silicon index and composite restorations of the four upper

incisors were baked on the working model (Figures 13(a) and

13(b)). While for teeth 11, 21, and 22 vestibular and incisal

areas were covered by the veneers, for the upper right lateral

(tooth 12) the mesiopalatal surface was also involved. No

dye spacer was used on dental cast so as to achieve optimal

adaptation of the restoration with minimal thickness of resin

composite cement. Microtextures detailing was accomplished

with finishing diamond burs. Composite restorations were

finally refined: the adjustment of rough contours and polishing with stones (Dura-green stones, Shofu Dental GmbH,

Ratingen, Germany) and disks (Sof-Lex, 3M ESPE) allowed

the fabrication of life-like veneers (Figure 14(a)). Definitive

restorations were seated on the working model and sent to

the clinician (Figure 14(b)).

6. Luting

After one week the patient returned for placement of the

final veneers and a try-in was carried out. The teeth were

cleaned with pumice and dried and a transparent try-in paste

was applied on the intaglio surface (Variolink try-in paste,

Ivoclar) (Figure 15). The marginal adaptation was checked

with a probe using dental loupes (Orascoptic HiRes 3.3x

magnification). An adhesive cementation was performed: the

dental enamel surface and the inner veneer surfaces were

treated before luting. The first one was etched with 38%

phosphoric acid for 30 seconds, washed for 60 seconds, and

gently dried (Figure 16); then a universal dental adhesive

(Scotchbond Universal, 3M ESPE) was applied using a microbrush.

The inner surface of the sectional veneers was sandblasted

with 50 micron Al2 O3 for 10 seconds at 2.8 bar pressure; the

indirect restorations were ultrasonically cleaned to remove

any remnants of alumina particles. A silane coupling agent

(ESPE-Sil, 3M ESPE) was used to facilitate the creation of

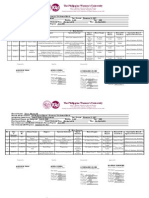

Table 1: Conditioning sequences for tooth and restoration surfaces.

1

2

3

4

5

1

2

3

4

5

6

Composite veneers pretreatment

Sandblasting with 50 micron aluminum oxide particles

(2.8 bar, 10 s, 1 cm)

Ultrasonic bath in ethanol (5 min)

Silane coupling agent application and evaporation (1 min)

Adhesive application (no photopolymerization)

Preheated resin composite application on the inner surface of

the veneer

Enamel surface pretreatment

Pumice cleaning of teeth surfaces

Rinsing with water (1 min)

Application of Mylar strips around teeth to be conditioned

Phosphoric acid (38%) etching of enamel (30 s)

Rinsing with water (1 min)

Adhesive application (no photopolymerization)

high bond strength to the cement. A coat of adhesive was

applied to the inner surface of the restorations and left

uncured. All surface treatments illustrated are reported in

Table 1.

A thin layer of preheated resin composite material was

used as the luting agent (Miris 2, Colt`ene Whaledent) and

directly applied to the inner surface of veneers. Restorations

were slowly seated on their respective teeth preparations;

pressure was applied in order to facilitate adaptation and

flow of the luting agent. While handling the veneers in place,

excess resin cement was carefully removed using a sickleshaped scaler (Novatech cement remover, Hu-Friedy Co.,

Chicago, USA). Glycerine gel was applied at the margins to

prevent an oxygen inhibition layer at the interface; subsequently a prolonged light curing was performed at facial,

incisal, and palatal sides for 90 seconds each (Bluephase LED

curing light, Ivoclar). The entire cementation procedure was

performed in two steps: first on central incisors and then

repeated on laterals. Following photopolymerization, residual

remnants of cement were removed with the help of a number

12 surgical blade and a dental probe; flossing was performed

at the interproximal areas to confirm patency at the contact

Case Reports in Dentistry

Figure 12: Wax-up for definitive restorations.

(a)

(b)

Figure 13: (a) Wax-up silicon index. (b) Microhybrid resin composite veneers fabrication.

(a)

(b)

Figure 14: (a)-(b) Finished and polished restorations.

Figure 15: Evaluation of the shade and fit using try-in paste.

Case Reports in Dentistry

Figure 16: Phosphoric acid (38%) etching of enamel (30 s).

Figure 17: Postoperative intraoral view.

points. Margins were finished and polished with diamond

burs, rubber points, and diamond polishing paste.

7. Esthetic Result

Intraoral and dentolabial views of the postoperative smile

enhancement at the follow-up, one week after the cementation procedure, are shown in the figures (Figures 17, 18(a),

and 18(b)); the final result met the patients expectations. The

obtained gingival health status, along with the resolution of

initial esthetic issues (in particular, lateral incisor rotation

and inadequate composite fillings) and nice integration of

indirect restorations, confirmed the success of this anterior

dentition rehabilitation.

8. Discussion

The cosmetic improvement of the smile is possible with both

direct [13, 14] and indirect techniques [12, 15]; the latter procedures might require more than one appointment but are preferred when multiple teeth are involved in the treatment plan

and accurate tooth reshaping or color matching is needed

[12]. With indirect techniques a previsualization of the final

esthetic result is extremely useful both for the clinician and

for the patient: in this way, desires and preferences related to

the new smile are tested before carrying out irreversible teeth

preparations [16, 17]. For these reasons, a diagnostic approach

is highly recommended when interventions are focused on

the anterior area of the mouth. In this case report, the gingival

outline of anterior teeth was considered satisfactory; in

other situations previsualization templates are also useful to

plan and/or carry out soft tissue recontouring, conditioning,

and/or gingivectomy [18]. While in the past full-crowns

were indicated in similar clinical scenarios, the improvement

in adhesive technologies has made possible a variety of

more conservative treatments. Different materials could be

used to fabricate additional veneers: feldspathic ceramics [2],

hybrid composites [12], or high-density ceramics (alumina,

glass-infiltrated zirconia, zirconia) [19]. The last, which is

usually CAD/CAM processed, needs more improvements

in the anterior area for translucency properties; moreover,

an optimal adhesive cementation protocol is not yet available [20, 21]. From a biological point of view, margins of

indirect veneers are most frequently placed at the juxta or

supragingival area; it has been documented that an extrasulcular location is able to provide adequate soft-tissue health

[22].

In this case report, a composite material has been selected

due to its quick and inexpensive delivering; a nanohybrid

composite with nanoparticles was preferred to porcelain due

to the ease of handling in the try-in and luting procedures.

Fractures of resin composite materials could also be simply

repaired with direct chairside techniques [23]. A preheated

Case Reports in Dentistry

(a)

(b)

Figure 18: (a)-(b) Postoperative dentolabial views; smile integration of final work.

light-cure composite has been suggested for cementation and

selected in our rehabilitation due to the ultrathin thickness of

laminates and for its low polymerization shrinkage and coefficient of thermal expansion compared to currently available

resin luting agents [24]. Among the disadvantages or resin

materials, some concerns have been raised regarding cytotoxicity [25]; however, this might not represent a problem

when no direct contact with living cells (i.e., pulp tissue)

exists. While the scientific literature is more extensive for

ceramic laminates, a recently published clinical trial (with

a 3-years follow-up) has reported no significant difference

in the survival rate of composite (87%) and ceramic (100%)

veneers; on the other hand, some surface quality changes

were more frequently observed for the resin materials (i.e.,

minor voids and defects and slight staining at the margins)

[26]. In addition, the survival rate and clinical performance of

composite or ceramic laminate veneers were not significantly

influenced when bonded onto intact elements or onto teeth

with preexisting composite restorations (when no caries

or infiltration is present, of course) [27, 28]. As a final

recommendation, like after the delivering of many other types

of indirect restorations, the dentist should plan a careful

follow-up program and give patients appropriate instructions for maintenance and preservation of the obtained

success.

9. Conclusions

The delivered treatment with resin composite additional

veneers followed the principles of enamel preservation

to achieve an esthetic rehabilitation of the four upper

incisors; the presented case report was based on an accurate

diagnostic process (wax-up and in vivo mock-up) which

allowed for minimally invasive, selective reduction of tooth

substance.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests

regarding the publication of this paper.

References

[1] J. L. Ferracane, Resin compositestate of the art, Dental

Materials, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 2938, 2011.

[2] M. Peumans, B. Van Meerbeek, P. Lambrechts, and G. Vanherle,

Porcelain veneers: a review of the literature, Journal of Dentistry, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 163177, 2000.

[3] P. Magne, J. Hanna, and M. Magne, The case for moderate,

guided prep indirect porcelain veneers in the anterior dentition. The pendulum of porcelain veneer preparations: from

almost no-prep to over-prep to no-prep, European Journal of

Esthetic Dentistry, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 376388, 2013.

[4] S. S. Azer, S. F. Rosenstiel, R. R. Seghi, and W. M. Johnston,

Effect of substrate shades on the color of ceramic laminate

veneers, Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry, vol. 106, no. 3, pp. 179

183, 2011.

[5] B. LeSage, Establishing a classification system and criteria for

veneer preparations, Compendium of Continuing Education in

Dentistry, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 104117, 2013.

[6] D. M. Layton and T. R. Walton, The up to 21-year clinical outcome and survival of feldspathic porcelain veneers: accounting

for clustering, The International journal of prosthodontics, vol.

25, no. 6, pp. 604612, 2012.

[7] D. M. Layton, M. Clarke, and T. R. Walton, A systematic

review and meta-analysis of the survival of feldspathic porcelain

veneers over 5 and 10 years, The International journal of

prosthodontics, vol. 25, no. 6, pp. 590603, 2012.

[8] D. Layton and T. Walton, An up to 16-year prospective study of

304 porcelain veneers, International Journal of Prosthodontics,

vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 389396, 2007.

[9] M. Peumans, J. De Munck, S. Fieuws, P. Lambrechts, G.

Vanherle, and B. Van Meerbeek, A prospective ten-year clinical

trial of porcelain veneers, Journal of Adhesive Dentistry, vol. 6,

no. 1, pp. 6576, 2004.

urk, S. Bolay, R. Hickel, and N. Ilie, Shear bond

[10] E. Ozt

strength of porcelain laminate veneers to enamel, dentine and

enamel-dentine complex bonded with different adhesive luting

systems, Journal of Dentistry, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 97105, 2013.

[11] S. J. Marshall, S. C. Bayne, R. Baier, A. P. Tomsia, and G. W.

Marshall, A review of adhesion science, Dental Materials, vol.

26, no. 2, pp. e11e16, 2010.

[12] F. Mangani, A. Cerutti, A. Putignano, R. Bollero, and L. Madini,

Clinical approach to anterior adhesive restorations using resin

Case Reports in Dentistry

[13]

[14]

[15]

[16]

[17]

[18]

[19]

[20]

[21]

[22]

[23]

[24]

[25]

[26]

[27]

composite veneers, The European Journal of Esthetic Dentistry,

vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 188209, 2007.

B. Korkut, F. Yankoglu, and M. Gunday, Direct composite

laminate veneers: three case reports, Journal of Dental Research,

Dental Clinics, Dental Prospects, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 105111, 2013.

Y. O. Zorba, Y. Z. Bayindir, and C. Barutcugil, Direct laminate

veneers with resin composites: two case reports with five-year

follow-ups, The Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice, vol.

11, no. 4, pp. E056E062, 2010.

S. Horvath and C.-P. Schulz, Minimally invasive restoration of

a maxillary central incisor with a partial veneer, The European

Journal of Esthetic Dentistry, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 616, 2012.

G. Gurel, S. Morimoto, M. A. Calamita, C. Coachman, and N.

Sesma, Clinical performance of porcelain laminate veneers:

outcomes of the aesthetic pre-evaluative temporary (APT)

technique, International Journal of Periodontics & Restorative

Dentistry, vol. 32, no. 6, pp. 625635, 2012.

P. Magne and M. Magne, Use of additive waxup and direct

intraoral mock-up for enamel preservation with porcelain

laminate veneers, The European Journal of Esthetic Dentistry,

vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1019, 2006.

K. Malik and S. Tabiat-Pour, The use of a diagnostic wax set-up

in aesthetic cases involving crown lengtheninga case report,

Dental Update, vol. 37, no. 5, pp. 303307, 2010.

T. F. Alghazzawi, J. Lemons, P.-R. Liu, M. E. Essig, and G. M.

Janowski, The failure load of CAD/CAM generated zirconia

and glass-ceramic laminate veneers with different preparation

designs, Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry, vol. 108, no. 6, pp. 386

393, 2012.

D. Re, D. Augusti, G. Augusti, and A. Giovannetti, Early

bond strength to low-pressure sandblasted zirconia: evaluation

of a self-adhesive cement, The European Journal of Esthetic

Dentistry, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 164175, 2012.

D. Re, D. Augusti, I. Sailer, D. Spreafico, and A. Cerutti, The

effect of surface treatment on the adhesion of resin cements to

Y-TZP, The European Journal of Esthetic Dentistry, vol. 3, no. 2,

pp. 186196, 2008.

P. Kosyfaki, M. del Pilar Pinilla Martn, and J. R. Strub, Relationship between crowns and the periodontium: a literature

update, Quintessence International, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 109126,

2010.

C. Maneenut, R. Sakoolnamarka, and M. J. Tyas, The repair

potential of resin composite materials, Dental Materials, vol.

27, no. 2, pp. e20e27, 2011.

L. J. Rickman, P. Padipatvuthikul, and B. Chee, Clinical applications of preheated hybrid resin composite, British Dental

Journal, vol. 211, no. 2, pp. 6367, 2011.

G. Nocca, V. D'Ant`o, V. Rivieccio et al., Effects of ethanol

and dimethyl sulfoxide on solubility and cytotoxicity of the

resin monomer triethylene glycol dimethacrylate, Journal of

Biomedical Materials Research B Applied Biomaterials, vol. 100,

no. 6, pp. 15001506, 2012.

M. M. Gresnigt, W. Kalk, and M. Ozcan, Randomized clinical

trial of indirect resin composite and ceramic veneers: up to 3year follow-up, The Journal of Adhesive Dentistry, vol. 15, no. 2,

pp. 181190, 2013.

M. M. M. Gresnigt, W. Kalk, and M. Ozcan,

Randomized

controlled split-mouth clinical trial of direct laminate veneers

with two micro-hybrid resin composites, Journal of Dentistry,

vol. 40, no. 9, pp. 766775, 2012.

[28] M. M. M. Gresnigt, W. Kalk, and M. Ozcan,

Clinical longevity

of ceramic laminate veneers bonded to teeth with and without

existing composite restorations up to 40 months, Clinical Oral

Investigations, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 823832, 2013.

Advances in

Preventive Medicine

The Scientific

World Journal

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com

Volume 2014

Case Reports in

Dentistry

International Journal of

Dentistry

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com

Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com

Scientifica

Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com

Volume 2014

Volume 2014

Pain

Research and Treatment

International Journal of

Biomaterials

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com

Volume 2014

Volume 2014

Journal of

Environmental and

Public Health

Submit your manuscripts at

http://www.hindawi.com

Journal of

Oral Implants

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com

Computational and

Mathematical Methods

in Medicine

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com

Volume 2014

Volume 2014

Journal of

Advances in

Oral Oncology

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com

Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com

Anesthesiology

Research and Practice

Journal of

Orthopedics

Drug Delivery

Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com

Volume 2014

Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com

Volume 2014

Journal of

Dental Surgery

Journal of

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com

BioMed

Research International

International Journal of

Oral Diseases

Endocrinology

Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com

Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com

Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com

Volume 2014

Radiology

Research and Practice

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com

Volume 2014

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Relining & RebasingDocument86 pagesRelining & RebasingJASPREETKAUR0410100% (1)

- Crocin Suspension and Crocin Suspension DS Product Info PDFDocument3 pagesCrocin Suspension and Crocin Suspension DS Product Info PDFJASPREETKAUR0410Pas encore d'évaluation

- Laminates and VennersDocument42 pagesLaminates and VennersJASPREETKAUR0410Pas encore d'évaluation

- Relining and Rebasing in Complete DenturesDocument58 pagesRelining and Rebasing in Complete DenturesJASPREETKAUR0410Pas encore d'évaluation

- MCQDocument8 pagesMCQJASPREETKAUR0410Pas encore d'évaluation

- A10 PDFDocument52 pagesA10 PDFJASPREETKAUR0410Pas encore d'évaluation

- JEducEthicsDent5241-2260055 061640Document6 pagesJEducEthicsDent5241-2260055 061640JASPREETKAUR0410Pas encore d'évaluation

- Article-PDF-sheen Juneja Aman Arora Shushant Garg Surbhi-530Document3 pagesArticle-PDF-sheen Juneja Aman Arora Shushant Garg Surbhi-530JASPREETKAUR0410Pas encore d'évaluation

- 809 Full PDFDocument10 pages809 Full PDFJASPREETKAUR0410Pas encore d'évaluation

- Oral Health Disparities Among The Elderly: Interdisciplinary Challenges For The FutureDocument10 pagesOral Health Disparities Among The Elderly: Interdisciplinary Challenges For The FutureJASPREETKAUR0410Pas encore d'évaluation

- Patient Consent in DentistryDocument5 pagesPatient Consent in DentistryJASPREETKAUR0410Pas encore d'évaluation

- Class. of Maxillectomy DefectsDocument10 pagesClass. of Maxillectomy DefectsJASPREETKAUR0410Pas encore d'évaluation

- Velopharyngeal InsufficiencyDocument9 pagesVelopharyngeal InsufficiencyJASPREETKAUR0410Pas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Laboratory Procedures RPDDocument30 pages1 Laboratory Procedures RPDJASPREETKAUR0410100% (4)

- Major RP TechnologiesDocument7 pagesMajor RP TechnologiesJASPREETKAUR0410Pas encore d'évaluation

- Geriatric Nutrition: CJ Segal-Isaacson Edd, RD Alice Fornari, Edd, RD Judy Wylie-Rosett, Edd, RDDocument64 pagesGeriatric Nutrition: CJ Segal-Isaacson Edd, RD Alice Fornari, Edd, RD Judy Wylie-Rosett, Edd, RDJASPREETKAUR0410Pas encore d'évaluation

- InTech-Medical Applications of Rapid Prototyping A New HorizonDocument21 pagesInTech-Medical Applications of Rapid Prototyping A New HorizonJASPREETKAUR0410Pas encore d'évaluation

- Immediate or Early Placement of Implants Following Tooth Extraction: Review of Biologic Basis, Clinical Procedures, and OutcomesDocument14 pagesImmediate or Early Placement of Implants Following Tooth Extraction: Review of Biologic Basis, Clinical Procedures, and OutcomesJASPREETKAUR0410Pas encore d'évaluation

- Functional Anatomy and TMJ PathologyDocument15 pagesFunctional Anatomy and TMJ PathologyJASPREETKAUR0410100% (1)

- 6 Restorationoftheendodonticallytreatedtooth 101219205957 Phpapp02Document100 pages6 Restorationoftheendodonticallytreatedtooth 101219205957 Phpapp02JASPREETKAUR0410100% (1)

- Occlusion and Occlusal Considerations in Implantology: I J D ADocument6 pagesOcclusion and Occlusal Considerations in Implantology: I J D AJASPREETKAUR0410Pas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- 2012 AAO Glossary - 0Document44 pages2012 AAO Glossary - 0Lucia DueñasPas encore d'évaluation

- Endoderm and DerivativesDocument3 pagesEndoderm and DerivativesCristian Giovanni Diaz PinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Nidhi D. Patel CVDocument3 pagesNidhi D. Patel CVNidhi PatelPas encore d'évaluation

- Example Multiple-Choice Questions (MCQS) : Only One Answer Is Correct - It Can Be Found at The BottomDocument2 pagesExample Multiple-Choice Questions (MCQS) : Only One Answer Is Correct - It Can Be Found at The BottomDrSheika Bawazir0% (1)

- DFGHJKDocument3 pagesDFGHJKcliffwinskyPas encore d'évaluation

- Operating Microscope in EndodonticsDocument24 pagesOperating Microscope in EndodonticsSiva KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- AOCMF Fellowship Brochure V - 03Document8 pagesAOCMF Fellowship Brochure V - 03Pandu HarsarapamaPas encore d'évaluation

- Term 3 Trial Exam STPM 2017Document11 pagesTerm 3 Trial Exam STPM 2017Viola Voon Li WeiPas encore d'évaluation

- Agile HospitalDocument8 pagesAgile HospitalMuhammad HafeezPas encore d'évaluation

- Up CHC 2016Document12 pagesUp CHC 2016tajesh rajPas encore d'évaluation

- Study Guide Cell SMSTR I 20 Nov 2013Document54 pagesStudy Guide Cell SMSTR I 20 Nov 2013Yuda DiraPas encore d'évaluation

- The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Forensic PsychiatryDocument727 pagesThe American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Forensic PsychiatryXarah Meza100% (10)

- Congenital Heart 22Document1 131 pagesCongenital Heart 22Maier Sorina100% (5)

- UERMMMC V LaguesmaDocument7 pagesUERMMMC V LaguesmaLornaNatividadPas encore d'évaluation

- Forensic Science & DNA FingerprintingDocument4 pagesForensic Science & DNA FingerprintingWalwin HarePas encore d'évaluation

- Ornap 2012Document2 pagesOrnap 2012Harby Ongbay AbellanosaPas encore d'évaluation

- ARCADocument14 pagesARCADOMINGO CASANOPas encore d'évaluation

- A Guide To The Newborn Intensive Care Unit (NICU)Document36 pagesA Guide To The Newborn Intensive Care Unit (NICU)Jean Wallace100% (3)

- JJM Medical College Davangere Admission - Fee - Seats - ExamDocument10 pagesJJM Medical College Davangere Admission - Fee - Seats - ExamRakeshKumar1987Pas encore d'évaluation

- Review 2 KLS 8Document13 pagesReview 2 KLS 8Taofik RidwanPas encore d'évaluation

- Alyssa Mellott ResumeDocument2 pagesAlyssa Mellott Resumeapi-281921437Pas encore d'évaluation

- Operations Management - Shouldice HospitalDocument2 pagesOperations Management - Shouldice HospitalRishabh SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Caesarean ThesisDocument8 pagesCaesarean Thesisdr.vidhyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Simplified-Phacoemulsification - 2013 PDFDocument247 pagesSimplified-Phacoemulsification - 2013 PDFRaulLopezJaime100% (3)

- TemplatesDocument5 pagesTemplatesLeon Darny Tahud PradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Contraception: QuestionsDocument11 pagesContraception: QuestionsNhoeExanisahPas encore d'évaluation

- The Philippine Women's UniversityDocument5 pagesThe Philippine Women's UniversityjenilayPas encore d'évaluation

- Pediatrics 2002 Ballard E63Document8 pagesPediatrics 2002 Ballard E63dentistalitPas encore d'évaluation

- MDI2conforme2017 18Document1 pageMDI2conforme2017 18Apryl Phyllis JimenezPas encore d'évaluation

- PartogramDocument3 pagesPartogrammuchalaithPas encore d'évaluation