Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

9 Ambarisha-Etal

Transféré par

editorijmrhsTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

9 Ambarisha-Etal

Transféré par

editorijmrhsDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

DOI: 10.5958/2319-5886.2015.00152.

6

Open Access

Available online at: www.ijmrhs.com

Research article

ADVERSE MATERNAL AND PERINATAL OUTCOMES IN GESTATIONAL

DIABETES MELLITUS

1

2 *

Ambarisha Bhandiwad , Divyasree B , Surakshith L Gowda

ARTICLE INFO

th

Received: 5 Jun 2015

th

Revised: 24 Jul 2015

th

Accepted: 5 Sep 2015

1

Authors details:

Professor and

2,3

Head, Junior Resident Department

of OBGY, JSS Medical College, JSS

University, Mysore, India

Corresponding author: Surakshith L

Gowda

Junior Resident Department of OBGY,

JSS Medical College, JSS University,

Mysore, India

Email: surakshithlgowda@gmail.com

Keywords: Gestational Diabetes

Mellitus, Maternal and Fetal

complications, Macrosomia,

Preeclampsia

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) are at

increased risk for many other health concerns with short and long-term

implications for both mother and child. They are at higher risk for glucosemediated macrosomia, hypertension, birth trauma, respiratory distress,

hypoglycemia, hyperbilirubinemia with increased neonatal intensive care

unit (NICU) admissions. Postpartum complications include obesity and

impaired glucose tolerance in the offspring and diabetes and cardiovascular

disease in the mothers. Objectives: To study the incidence of maternal

and fetal co-morbidities associated with GDM. Materials and Methods:

This is a retrospective observational study where cases with GDM were

analyzed for maternal and fetal complications. Results: 189 cases were

detected to be Gestational Diabetes Mellitus, out of which 63.49% cases

developed co-morbidities with GDM. 11.11% cases developed

preeclampsia, 9.52% had polyhydramnios, 5.8% patients went into preterm

labour, 3 cases had Antepartum Haemorrhage and one case had

Postpartum Haemorrhage. 19.57% cases developed macrosomia,

hypoglycemia was seen in 7.40% babies and hyperbilirubinemia in 3.70%

babies. 6 Intra Uterine Deaths and 2 still borns were documented.

Conclusion: GDM is a condition which is worth monitoring and treating,

since it has been demonstrated that good metabolic control maintained

throughout gestation can reduce maternal and fetal complications.

INTRODUCTION

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) is commonly

defined as carbohydrate intolerance that first becomes

[1]

apparent during pregnancy. Women with GDM are at

increased risk for many other health concerns with short

and long-term implications for both mother and child.

Women with GDM are at higher risk for glucosemediated macrosomia, hypertension, adverse pregnancy

outcomes (stillbirth, birth trauma, cesarean section, preeclampsia,

eclampsia,

respiratory

distress,

hypoglycemia,

hyperbilirubinemia,

polycythemia,

hypocalcemia, increased neonatal intensive care unit

admissions) and neonatal adiposity with its long-term

[2, 3]

sequelae including childhood obesity and diabetes.

Postpartum complications include obesity and impaired

glucose tolerance in the offspring and diabetes and

[3]

cardiovascular disease in the mothers. Women who

have GDM are at higher risk of developing T2DM in the

future.This risk has been shown to be as high as 50% for

[4]

future T2DM risk.

The ADA recommends that all

women with GDM be screened at six to 12 weeks after

delivery for persistent diabetes and then every three

[5]

years thereafter

where as the DIPSI recommends to

screen women with GDM at 6 weeks, 6 months and then

yearly thereafter for persistent diabetes. This condition is

worth monitoring and treating, since it has been

demonstrated that good metabolic control maintained

throughout gestation can reduce maternal and fetal

[1]

complications.

Ambarisha et al.,

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design: This is a retrospective observational

study

Study period and location: The study was done

between January 2013 to December 2014, at JSS

Hospital, Mysore

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the

Institutional Ethics committee

Inclusion criteria: All antenatal patients who were

diagnosed as GDM and who delivered during the study

period available from the record section

Exclusion Criteria: Patients with oral glucose challenge

test value of <140 mg/dl, incomplete data of the patient

How GDM was diagnosed ?: All pregnant women were

screened and diagnosed with Diabetes In Pregnancy

[6]

Study group India (DIPSI) criteria i.e. irrespective of the

timing of the last meal, as and when the pregnant

women entered the antenatal clinic, she was given 75gm

oral glucose. Then two hours later, plasma glucose was

estimated by Glucose oxidase - peroxidase method. 2hr

post plasma glucose value of 140 mg/dl was diagnostic

of GDM and those patients were included in the study.

All women were screened between 24-28 weeks of

gestation and women with high risk factors such as age

>30 yrs, obesity, family history of diabetes, previous bad

obstetric history, history of GDM in previous pregnancy

were screened earlier at 12 16 weeks of gestation and

those diagnosed with GDM were included in the study,

775

Int J Med Res Health Sci. 2015;4(4):775-777

but in a normally glucose tolerant women the test was

repeated again at 32 34 weeks.

Methodology:

The incidence of maternal (i..e, Preeclampsia,

Polyhydramnios,

Preterm

labour,

Antepartum

Haemorrhage, Postpartum Haemorrhage) and fetal

complications ( i.e., Macrosomia, ICU admissions,

Hypoglycemia, Hyperbilubinemia, Intra Uterine Death,

Still born) which developed in those GDM patients were

retrospectively analyzed from the medical records and

the data was presented as percentage of complications.

RESULTS

A total of 2070 cases delivered during the study period in

which 189 cases were detected to be Gestational

Diabetes Mellitus, out of which 120 (63.49%) cases

developed co-morbidities with GDM.

Maternal complications: 21 cases (11.11%) developed

preeclampsia, 18 cases (9.52%) had polyhydramnios, 11

patients went into preterm labour i.e. 5.8%, 3 cases had

APH (1.58%) and one case had PPH.

Fetal complications: 37 cases developed macrosomia,

i.e. 19.57% (birth weight for Indian standards was taken

as >3500 gms), 22 babies were admitted to NICU and 14

developed hypoglycemia (7.40%) and 7 babies had

hyperbilirubinemia (3.70%). 6 Intra Uterine Deaths

(3.17%) and 2 still borns (1.05%) were documented.

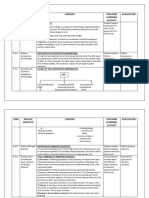

Table 1: Maternal & Fetal Complications with GDM

Maternal complications

Fetal complications

N (%)

Preeclampsia

21(11.1)

Macrosomia

37 (19.6)

Polyhydramnios 18 (9.5)

NICU

22 (11.6)

admissions

Preterm labour 11 (5.8) Hypoglycemia 14 (7.40)

Antepartum

3 (1.58)

Hyperbilirubin 7 (3.70)

Haemorrhage

emia

Postpartum

1 (0.52)

IUD

6 (3.17)

Haemorrhage

Still borns

2 (1.5)

DISCUSSION

The incidence of GDM in the present study was found to

be 9.13 %. In India the prevalence of GDM varied from

[6]

3.8 to 21% across the different regions and 63.49% of

GDM cases developed complications. Macrosomia in

this study was found to be 19.57% which is similar to a

[7]

study in which the incidence of macrosomia was 18%.

Currently, it is not known whether the overlap in GDM

and hypertensive disorders reflects a common causal

pathway. Both GDM and hypertensive disorders are

associated with factors such as insulin resistance,

[8]

inflammation, and maternal fat deposition patterns . In

a randomized MiG trial, which only included GDM

women, about 5.0% of women had gestational

[9]

hypertension and 6.3% had pre-eclampsia. However,

[10]

the randomized ACHOIS trial reported that 15% of its

GDM population had pre-eclampsia, and in the present

study Pre eclampsia was associated with GDM in

11.11% of patients.

Ambarisha et al.,

In 1987, Cousins reviewed the literature published in

English from 1965 to 1985 on the impact of diabetes on

the frequency and severity of obstetric complications.

[11]

Hydramnios was found to be 5.3%

where as it was

9.52% in the present study

Preterm delivery is usually defined as delivery <37

weeks gestation. While acknowledged as a risk of GDM,

spontaneous preterm delivery is less common compared

[3]

with other adverse outcomes. . In the present study the

incidence of preterm delivery was 5.3%. In the HAPO

study, approximately 1608 of the 23,316 participants

(6.9%) experienced preterm delivery (both induced and

spontaneous), compared with 9.6% of infants who were

LGA and 8.0% of infants who underwent intensive

[12]

neonatal care admission.

The association between

GDM and preterm delivery may be partially explained by

the coexistence of other conditions with GDM that may

lead to indicated or induced preterm delivery. Such

conditions include pre-eclampsia and hypertensiveassociated conditions, such as intrauterine growth

restriction

and

placental

abruption.

However,

spontaneous preterm birth, or birth in the absence of

conditions prompting medical intervention, accounts for

approximately three-quarters of preterm births and is not

[12, 13]

associated with GDM.

. In the present study 3 cases

had antepartum haemorrhage and one patient had post

partum haemorrhage following a cesarean section where

the neonatal birth weight was 3.9 kgs. In this study 22

babies had NICU admission and 14 babies were

admitted for neonatal hypoglycemia. The reasons for

neonatal hypoglycemia include physiologic fluctuations in

glucose seen in GDM women, apart from treatment.

Maternal hyperglycemia is thought to lead to excess fetal

glucose exposure and fetal hyperinsulinemia. In turn,

fetal hyperinsulinemia is thought to lead to hyperplasia of

fat tissue, skeletal muscle, and subsequent neonatal

[14]

hypoglycemia.

In ACHOIS, the prevalence of clinical

hypoglycemia was 7% in GDM receiving intervention and

[10]

5% in GDM not receiving intervention,

which was

similar to 7.4% in the present study.

Hyperbilirubinemia is more common among women with

GDM than in women without GDM. Maternal

hyperglycemia and the subsequent induction of fetal

hyperinsulinemia and reduced oxygenation are

hypothesized to lead to increased fetal oxygen uptake,

fetal

erythropoiesis,

and

subsequent

[15]

[12]

hyperbilirubinemia.

In the HAPO study

8.3% of the

babies were affected with hyperbilirubinemia in

comparison with 3.7% in this study. In more recent years

and in industrialized nations, stillbirth is an uncommon

outcome, even among women with glucose intolerance.

Reduced stillbirth rates have been attributed to initiation

of insulin therapy combined with closer monitoring and

[16]

subsequent induction of labor as necessary. In a study

population consisting primarily of women with GDM, the

[17]

stillbirth rate was approximately 1.4 per 1000 births. .

3.17% fetal death an 1.05% neonatal death were

documented in this study. In HAPO, only 130 women

(0.56%) of the 23,316 deliveries experienced a perinatal

death, 89 of which were fetal and 41 of which were

[12]

neonatal.

776

Int J Med Res Health Sci. 2015;4(4):775-777

The effects of GDM upon fetal health may still be

conceptualized through the framework of the Pederson

[18]

hypothesis,

which postulated that intrauterine

exposure could lead to permanent changes in fetal

metabolism. During the GDM pregnancy, the fetus may

be imprinted or programmed, resulting in excess fetal

growth, decreased insulin sensitivity, and impaired

insulin secretion. In the short term, elevated infant birth

weight confers perinatal risks, such as shoulder dystocia

and infant hypoglycemia. In the longer term, altered fetal

metabolism may be associated with impaired glucose

[19]

tolerance during early youth and adolescence.

The

reduced beta-cell reserve in GDM women can manifest

[20]

in the decade after delivery. Even among women who

have a normal postpartum glucose tolerance test, the

risk of future diabetes may be up to seven-fold higher

[21]

than in women without histories of GDM.

As many as

one-third of women with diabetes may have been

[22]

affected by prior GDM.

In turn, the increased risk of

diabetes

is

associated

with

future

maternal

[23]

cardiovascular disease.

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of GDM will continue to increase as

obesity rates rises. There are sufficient evidences to

show the association between hyperglycemia and

adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes in the mother

and offspring. A close attention to the fetal growth along

with maternal glucose and weight monitoring during

pregnancy and also in the postpartum period will

minimize adverse outcomes. GDM is a condition which is

worth monitoring and treating, since it has been

demonstrated that good metabolic control maintained

throughout gestation can reduce maternal and fetal

complications.

Conflict of Interest: None

REFERENCES

1. Metzger BE, Coustan DR (Eds.): Proceedings of the

Fourth International Workshop- Conference on

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care

1998;21(suppl. 2):B1-B167.

2. Langer O. Management of gestational diabetes:

pharmacologic treatment options and glycemic

control. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am.

2006;35(1):53-78.

3. Gestational diabetes: risks, management, and

treatment options, Int J Womens Health. 2010; 2:

339351

4. Metzger BE. Long-term outcomes in mothers

diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus and

their offspring. Clin Obstet Gynecol.2007;50:972-79.

5. ADA Clinical Practice Guidelines 2011. Diabetes

Care. 2011;34(suppl 1):S4-S5.

6. Seshaiah V, Sahay BK, Das AK, Shah S, Banerjee

S, Rao PV et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus-Indian guidelines. J Indian Med Assoc. 2009

Nov;107(11):799-802, 804-806.

7. Vedavathi KJ , Swamy Rm , Kanavi Roop

Shekharappa , Venkatesh G , Veerananna HB

Influence of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus on Fetal

Ambarisha et al.,

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

growth parameters. Int J Biol Med Res. 2011; 2(3):

832-834

Seely E, Solomon C. Insulin resistance and its

potential role in pregnancy-induced hypertension. J

Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(6):23932398.

Rowan J, Hague W, Gao W, Battin M, Moore M.

MiG Trial Investigators. Metformin versus insulin for

the treatment of gestational diabetes. N Engl J Med.

2008;358(19):20032015.

Crowther C, Hiller J, Moss J, et al. Effect of

treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus on

pregnancy

outcomes.

N

Engl

J

Med.

2005;352(24):24772486.

Cousins L: Pregnancy complications among diabetic

women: review 1965-1985. Obstet Gynecol Surv ,

1987;42:140-49

HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group.

Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N

Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):19912002.

ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins Obstetrics.

ACOG practice bulletin. Management of preterm

labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;82(1):127135.

HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group.

Hormonal and metabolic factors associated with

variations in insulin sensitivity in human pregnancy.

Diabetes Care. 2010;33(2):356360.

Ferrara A, Weiss N, Hedderson M, et al. Pregnancy

plasma glucose levels exceeding the American

Diabetes Association thresholds, but below the

National Diabetes Data Group thresholds for

gestational diabetes mellitus, are related to the risk

of neonatal macrosomia, hypoglycaemia, and

hyperbilirubinaemia. Diabetologia. 2007;50(2):298

306.

ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management

guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet

Gynecol. 2001;98(3):525538.

Girz B, Divon M, Merkatz I. Sudden fetal death in

women with well-controlled intensively monitored

gestational diabetes. J Perinatol. 1992;12(3):22933

Pedersen J. Weight and length at birth in infants of

diabetic mothers. Acta Endocrinol. 1954;16(4):330

42

Catalano P, Kirwan J, Haugel-de Mouzon S, King J.

Gestational diabetes and insulin resistance: Role in

short- and long-term implications for mother and

fetus. J Nutr. 2003;133(5 Suppl 2):S1674S1683.

Kim C, Newton K, Knopp R. Gestational diabetes

and incidence of Type 2 diabetes mellitus: A

systematic

review.

Diabetes

Care.

2002;25(10):186268.

Bellamy L, Casas J, Hingorani A, Williams D. Type

2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet.

2009;373(9677):177379.

Cheung N, Byth K. Population health significance of

gestational

diabetes.

Diabetes

Care.

2003;26(7):200509.

Carr D, Utzschneider K, Hull R. Gestational diabetes

mellitus increases the risk of cardiovascular disease

in women with a family history of Type 2 diabetes.

Diabetes Care. 2006;29(9):207883.

777

Int J Med Res Health Sci. 2015;4(4):775-777

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Ultrasound Notes For Trainees: DR Phurb DorjiDocument16 pagesUltrasound Notes For Trainees: DR Phurb DorjiooiziungiePas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Induction of Labor With Oxytocin - UpToDateDocument54 pagesInduction of Labor With Oxytocin - UpToDateJhoseline CamposPas encore d'évaluation

- Bridging Courses for Overseas Trained DoctorsDocument7 pagesBridging Courses for Overseas Trained Doctorsphyo waiPas encore d'évaluation

- Antepartum HemorrhageDocument21 pagesAntepartum HemorrhageNidhi SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Radiology of Obstetrics and GynaecologyDocument61 pagesRadiology of Obstetrics and GynaecologyMUBIRU SAMUEL EDWARDPas encore d'évaluation

- Skilled Birth Attendance HandbookDocument69 pagesSkilled Birth Attendance HandbookKripa Susan100% (2)

- Ijmrhs Vol 4 Issue 2Document219 pagesIjmrhs Vol 4 Issue 2editorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- 47serban Turliuc EtalDocument4 pages47serban Turliuc EtaleditorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- Ijmrhs Vol 4 Issue 4Document193 pagesIjmrhs Vol 4 Issue 4editorijmrhs0% (1)

- Ijmrhs Vol 4 Issue 3Document263 pagesIjmrhs Vol 4 Issue 3editorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- Ijmrhs Vol 2 Issue 3Document399 pagesIjmrhs Vol 2 Issue 3editorijmrhs100% (1)

- Ijmrhs Vol 3 Issue 3Document271 pagesIjmrhs Vol 3 Issue 3editorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- Ijmrhs Vol 1 Issue 1Document257 pagesIjmrhs Vol 1 Issue 1editorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- Ijmrhs Vol 3 Issue 4Document294 pagesIjmrhs Vol 3 Issue 4editorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- Ijmrhs Vol 2 Issue 2Document197 pagesIjmrhs Vol 2 Issue 2editorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- Ijmrhs Vol 3 Issue 1Document228 pagesIjmrhs Vol 3 Issue 1editorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- 45mohit EtalDocument4 pages45mohit EtaleditorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- Ijmrhs Vol 3 Issue 2Document281 pagesIjmrhs Vol 3 Issue 2editorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- Ijmrhs Vol 2 Issue 4Document321 pagesIjmrhs Vol 2 Issue 4editorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- Ijmrhs Vol 2 Issue 1Document110 pagesIjmrhs Vol 2 Issue 1editorijmrhs100% (1)

- Ijmrhs Vol 1 Issue 1Document257 pagesIjmrhs Vol 1 Issue 1editorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- 41anurag EtalDocument2 pages41anurag EtaleditorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- 48 MakrandDocument2 pages48 MakrandeditorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- Pernicious Anemia in Young: A Case Report With Review of LiteratureDocument5 pagesPernicious Anemia in Young: A Case Report With Review of LiteratureeditorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- 40vedant EtalDocument4 pages40vedant EtaleditorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- 43chaitali EtalDocument3 pages43chaitali EtaleditorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- Recurrent Cornual Ectopic Pregnancy - A Case Report: Article InfoDocument2 pagesRecurrent Cornual Ectopic Pregnancy - A Case Report: Article InfoeditorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- Williams-Campbell Syndrome-A Rare Entity of Congenital Bronchiectasis: A Case Report in AdultDocument3 pagesWilliams-Campbell Syndrome-A Rare Entity of Congenital Bronchiectasis: A Case Report in AdulteditorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- 38vaishnavi EtalDocument3 pages38vaishnavi EtaleditorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- 36rashmipal EtalDocument6 pages36rashmipal EtaleditorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- 37poflee EtalDocument3 pages37poflee EtaleditorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- 35krishnasamy EtalDocument1 page35krishnasamy EtaleditorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- 33 Prabu RamDocument5 pages33 Prabu RameditorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- 34tupe EtalDocument5 pages34tupe EtaleditorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- 32bheemprasad EtalDocument3 pages32bheemprasad EtaleditorijmrhsPas encore d'évaluation

- Biochemical Investigation in PregDocument28 pagesBiochemical Investigation in PregRana VandanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Guideline for Managing Eclampsia and Severe Pre-EclampsiaDocument15 pagesGuideline for Managing Eclampsia and Severe Pre-EclampsiaMegane YuliPas encore d'évaluation

- Tugas 2 HukKes KKIDocument12 pagesTugas 2 HukKes KKINikolasKosasihPas encore d'évaluation

- Prenatal screening testDocument2 pagesPrenatal screening testEva.linePas encore d'évaluation

- IVF TRAINING For EMBRYOLOGIST & GYNAECOLOGISTDocument3 pagesIVF TRAINING For EMBRYOLOGIST & GYNAECOLOGIST24x7emarketingPas encore d'évaluation

- Second and Third Trimester Screening For Fetal AnomalyDocument12 pagesSecond and Third Trimester Screening For Fetal AnomalyIqra NazPas encore d'évaluation

- Cervical IncompetenceDocument30 pagesCervical IncompetenceSignor ArasPas encore d'évaluation

- CLINICAL GUIDELINE FOR POSTPARTUM BLADDERDocument9 pagesCLINICAL GUIDELINE FOR POSTPARTUM BLADDERHanya BelajarPas encore d'évaluation

- English Assignment ConversationDocument4 pagesEnglish Assignment ConversationSri HalipahPas encore d'évaluation

- Rupture of UterusDocument5 pagesRupture of UterussamarbondPas encore d'évaluation

- Gynea & Obs 26-30Document6 pagesGynea & Obs 26-30Wafiyah AwaisPas encore d'évaluation

- Neonatal ResuscitationDocument36 pagesNeonatal ResuscitationDemelash SolomonPas encore d'évaluation

- Antepartum Hemorrhage Causes Fetal DistressDocument4 pagesAntepartum Hemorrhage Causes Fetal Distressvenus eugenioPas encore d'évaluation

- Mannual Removal of Placenta: Presented By-Bhawna Joshi MSC. (N) 2 YearDocument23 pagesMannual Removal of Placenta: Presented By-Bhawna Joshi MSC. (N) 2 YearBhawna JoshiPas encore d'évaluation

- Acute Uterine InversionDocument6 pagesAcute Uterine InversionBima GhovaroliyPas encore d'évaluation

- Biophysical ProfileDocument1 pageBiophysical ProfileCruz YrPas encore d'évaluation

- College of Health Sciences Yarsi Mataram DIII Midwifery Studies Program Final Project Report, July 2nd, 2019 Yana Fiqratus Shofa (037 SYEIB 16)Document3 pagesCollege of Health Sciences Yarsi Mataram DIII Midwifery Studies Program Final Project Report, July 2nd, 2019 Yana Fiqratus Shofa (037 SYEIB 16)Yana ShofaPas encore d'évaluation

- Example of Delivery NoteDocument1 pageExample of Delivery NoteRuDy RaviPas encore d'évaluation

- AC8A9EE0-EggFreezingProcesseditDocument9 pagesAC8A9EE0-EggFreezingProcesseditFrida AtallahPas encore d'évaluation

- CR3 RobbbDocument86 pagesCR3 RobbbIhsan Rasyid YuldiPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Complications of L&D PowerDocument84 pages1 Complications of L&D PowerMarlon Glorioso II100% (1)

- MCN 209 Obgyne Rotation: Postpartum HemorrhageDocument10 pagesMCN 209 Obgyne Rotation: Postpartum HemorrhageMonique LeonardoPas encore d'évaluation

- Preliminary Offer Document (12 May 2015) PDFDocument329 pagesPreliminary Offer Document (12 May 2015) PDFInvest StockPas encore d'évaluation

- Vbac (Vaginal Birth After C-Section) : RA. Nurafrilya Fitria SariDocument13 pagesVbac (Vaginal Birth After C-Section) : RA. Nurafrilya Fitria Sariafirdha27Pas encore d'évaluation