Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Construction Project Planning and Scheduling and The Microcomputer - tcm45-341203

Transféré par

farhanyazdaniTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Construction Project Planning and Scheduling and The Microcomputer - tcm45-341203

Transféré par

farhanyazdaniDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Construction project

planning and scheduling

and the microcomputer

BY JAMES J. ADRIAN

CONSULTANT

STEPS REQUIRED FOR CONSTRUCTION PROJECT SCHEDULING AND USE OF COMPUTER

Must be done

manually

1. Define activities for project

2. Determine activity logic

3. Determine duration for activities

4. Determine float or contingency

duration to add to activity durations

X

X

8. Use algorithms (and computer?)

to plan and level resources

X

X

10. Perform calculations to prepare

a revised project schedule

11. Take steps to react to problems

determined from analysis of schedule

7. Perform project schedule

network calculations

9. Obtain jobsite date to

update schedule

Computer very Computer almost

advantageous

essential

5. Draw the project schedule network

6. Obtain subcontractor input

Computer can

indirectly help

X

X

Figure 1

t is possible that more microcomputers have been

purchased by the construction industry and its practitioners than by any other industry. Many software

p ro g rams for the construction industry are now

available to perform functions such as accounting, estimating and scheduling. Because accounting and estimating software programs follow most contractors existing manual procedures, the contractor has to adjust

his operating procedures only slightly to benefit from

computerization in these areas. Un f o rt u n a t e l y, the

same cannot be said of computer software for planning

and scheduling.

Establish manual scheduling procedures first

Project owners have only recently acted to pre ve n t

costly time and cost overruns by requiring contractors to

submit schedules. Until formalized scheduling became

a condition for awarding a contract, contractors often

undertook the construction of a significant-size project

with no schedule on paper. Scheduling techniques such

as the critical path method (CPM) we re nt well understood, bar charts were seldom used and the contractor

typically carried the schedule in his head. Because contractors we re nt even using manual procedures for

scheduling, computerization at this stage was analogous

to teaching a baby to run before it can walk.

Computers alone cant develop schedules that will increase productivity, improve quality control or reduce

the number of delays at construction sites. A computer

has only three capabilities that make computeri ze d

scheduling superior to manual processes. Co m p a re d

with a person, a computer can calculate faster, make calculations more accurately and organize more information in its much larger memory. Howe ve r, the computer

duration

20 days

___________________

Erect Wall Forms

Figure 2

by itself cannot obtain accurate input data. These data

must come from the constructor, who must derive them

from his own, accurate manual procedures.

Preparation and use of effective

construction schedules

Fo rm a l i zed construction planning and scheduling

management techniques, including CPM, can help the

constructor fulfill the requirements for a schedule. While

manual preparation of a CPM schedule can be tedious,

encouraging time-saving guesstimates which may render the results useless, computer assistance can increase

accuracy while reducing the time required to complete

calculations necessary to the production of a schedule.

Figure 1 summarizes the steps essential to the preparation and use of effective manual and computerized construction schedules.

Define activities. It is necessary to determine whether

forming walls, placing reinforcing bars and placing concrete walls is defined as three jobs or just one function,

erecting walls. Breaking jobs down into too many separate activities tends to discourage jobsite personnel from

using such detailed schedules. On the other hand, too

little detail makes a project schedule practically useless.

When defining activities, keep in mind that they

should be compatible with the intended purpose and

use of the schedule, compatible with the estimate breakdown, compatible with field reporting for cost control,

and compatible with the billing system that is used for

making progress pay requests.

Determine activity logic. Whether a project schedule

is produced manually or by computer, its activities

should be sequenced to model or represent the planned

actual construction process. For example, the pouring of

concrete walls must follow the placing of footings. In

addition to this technical logic, the project schedule

must also recognize resource logic and preference logic

of the builder. Resource logic may in fact take into account limited resources, such as too few carpenters to allow forming both the north and east walls at the same

time. Preference logic is the reasoning behind the decision of a contractor to do one activity after another, despite the ability and availability of resources, usually for

economic reasons.

Determine activity duration. A project schedule is only as good as the accuracy of its activity durations. The

only way to calculate an activity duration is to determine

it based on the quantity of work to do, the estimated productivity, and the establishment of a crew size. The computer by itself cannot determine the durations for the

contractor.

Figure 3

Figure 2 illustrates the symbol for the activity called

Erect Wall Fo rm s.

Step 1: Determine quantity of work

8000 square feet of contact area

Step 2: Estimate productivity

10.0 man-hours/100 sfca

Step 3: Establish crew size

5 workers

Step 4: Calculate durations:

(10 mh) (8,000 sfca)

= 20 days

(100 sfca) (5 mh/hr) (8 hrs/day)

No matter how sophisticated a computerized scheduling program is, the schedule will be inaccurate unless

the above calculation is made correctly. A CPM software

program cannot ensure an accurate duration.

Determine float or contingency durations for activities. Some extra time should be built into activity durations to acknowledge what will likely go wrong. Naturally, severe weather, material shortages and equipment

breakdowns dont affect all activities of all construction

projects equally, so this may take careful thought.

Obtain subcontractor input. In order to be of the most

benefit planning and controlling a project, the schedule

Activity

DUR

EST

EFT

LST

LFT

FF

FFP

TF

11

16

16

16

24

24

26

24

26

26

28

13

11

16

16

20

16

20

20

28

20

28

28

34

28

34

20

22

37

39

17

17

17

34

39

34

39

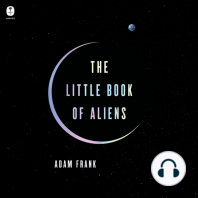

Figure 4

Legend:

DUR = Duration

EST = Earliest Start Time

EFT = Earliest Finish Time

LST = Latest Start Time

LFT = Latest Finish Time

FF = Free Float

FFP = Free Float Prime

TF = Total Float

should incorporate meaningful activity logic and durations from all contractors working on the project. These

c o n t ra c t o r s, in turn, should understand the schedule

and cooperate with it.

Draw the project schedule. Figure 3 illustrates a very

small drawn schedule. While a computerized plotting

program yields impressive results, a bar chart is not difficult to plot or draw manually once activities are defined, logic determined, and durations established.

Pe rf o rm schedule calculations. For big projects with

numerous activities, the computer user saves seve ra l

hours and perhaps even days at this point. If a mathematical scheduling technique such as CPM is used, the

calculations necessary to determining project duration,

activity start and finish times, and activity floats can be

done by a computer in almost no time at all. Example

output from one of these programs is shown in Figure 4.

Use computerized software to plan and manage resources. Modern computer software can use CPM as a

basis for leveling or allocating various project resources

such as labor, equipment or cash for specific purposes

like minimizing project costs. Although sophisticated

p ro g rams can do almost every type of resource allocation imaginable, it is important to question the usefulness of every application.

Obtain field data to update schedule. Two months into a 10-month project, one can argue that a new 8month project is just beginning. Obtaining field data to

reflect the events to date is fundamental to the updating

of a project schedule. Ac c u ra t e, complete and timely

field reporting is essential to the updating of a project

plan and, clearly, cannot be accomplished by the computer alone.

Make calculations to prepare a revised or working

schedule. A schedule that is not revised and kept current may be worse than no schedule at all. The strongest

argument for computerized planning is the ease and

speed of performing the otherwise tedious and timeconsuming mathematics necessary to the preparation of

revised schedules throughout the duration of a project.

Take steps to react to problems determined from

analysis of schedule. The purpose of using a formalized

schedule during the construction project is to detect

possible problems in time to take corrective action. The

computer only processes information that can clarify

such problems. Follow-up must take the form of manual interpretation and intervention.

The majority of the above steps can be perf o rm e d

manually, and many of them can only be perf o rm e d

manually. Yet the computer can play an important role

in getting the most out of effective manual scheduling

procedures.

Choosing microcomputer scheduling software

Four basic types of microcomputer programs are useful for preparing effective construction project plans and

schedules:

Programs that quickly and accurately make basic

scheduling calculations about project duration, activity early and late start and finish times, and project and

activity floats

Programs for updating project schedules to reflect job

progress and revised projections

Programs that plot (via graphic capability and a pen)

project plans graphically in 2 dimensions

Programs that use algorithms (optimal mathematical

solutions) to plan, manipulate and level re s o u rc e s

such as labor, equipment and cash

Although it is possible to purchase a single software

p ro g ram for all 4 applications, the expense and usefulness of such equipment should be carefully considered.

The first two programs listed above, which can be purchased separately, are likely to be the most beneficial.

The rapid improvements in quality and prices in the

computer field should encourage the constructor to purchase for his immediate needs only. By the time his manual procedures are ready to support more advanced software, a better, less expensive program will likely be

available.

After determining what software program to buy, be

careful in choosing a vendor. Consider reputation and

a p p roximate number of installations, as well as

whether the vendor provides backup service, good program documentation and program revisions. Because

the vendor may know little about construction project

scheduling applications, the constructor should keep

the following concerns in mind as he shops for specific

software programs:

1. The program should contain clear and complete data editing routines that enable the user to correct input entries such as activity names, activity logic or

durations.

2. The software should contain complete and efficient

error routines that prevent input errors that can destroy minutes or even hours of good input.

3. To the degree possible, the scheduling pro g ra m

should integrate with the firms estimating and cost

control programs. Efficiency is increased if definitions

of activities for scheduling, work items for estimating

and cost objects for cost control are compatible.

4. The program should reflect the needs of the constructor and should be designed to think like him. Many

project planning and scheduling programs may require input or produce output that is inconsistent

with the functions and needs of the construction industry.

5. The software should be flexible in handling va ri o u s

levels of detail. A conceptual schedule, a milestone

schedule and a detailed schedule to be used by the

foreman to run a project all require different levels of

detail which should be integrated into the program.

6. The software should be able to accommodate the

many change orders that chara c t e ri ze the construction process.

7. Output reports produced by the program should be

easily understood and available in different degrees

of detail for the various managers who use the reports.

8. The program should be able to handle any number of

project activities, from few to many.

9. The software program should enable the firm to calculate percent complete based on project pro g re s s

and enable efficient calculation of the progress payment requests.

10. Any charts or bar charts the program creates should

be produced on inexpensive printers and should be

easy to handle and use at the jobsite.

11. The purchase price of a software program does not

necessarily reflect its quality or degree of usefulness.

If a vendor expends $100,000 to develop a software

program for scheduling and can sell 1000 copies, he

can break even if he markets it for $100 a copy. A

$1000 price tag may mean the vendor could sell only

100 copies!

A construction project planning and scheduling program should be relatively inexpensive, which means it

should cost less than $500. There is a high probability

that whatever a construction company purchases today

will be better and less expensive a year from now.

Fo rm a l i zed scheduling techniques and the microcomputer can go hand in hand to aid the constructor in

better planning and scheduling of projects. To benefit

most, the constructor should ready his manual procedures; he should be realistic about what the computer

can do and about what he needs the computer to do for

him; and he should do a careful performance and cost

analysis of the many programs that are available.

PUBLICATION#C860153

Copyright 1986, The Aberdeen Group

All rights reserved

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Appendix A: SPU Design ChecklistDocument14 pagesAppendix A: SPU Design ChecklistfarhanyazdaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Gate Model PapersDocument10 pagesGate Model PapersfarhanyazdaniPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Unit 2 PDFDocument36 pagesUnit 2 PDFfarhanyazdaniPas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Al-Bader 13213.8KV SubstationDocument18 pagesAl-Bader 13213.8KV SubstationfarhanyazdaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Project Title: Replacement of 4.16 KV Switchgears & LV Switchboards @Swc-1 Marafeq JubailDocument3 pagesProject Title: Replacement of 4.16 KV Switchgears & LV Switchboards @Swc-1 Marafeq JubailfarhanyazdaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Appendix A: SPU Design ChecklistDocument14 pagesAppendix A: SPU Design ChecklistfarhanyazdaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Applying Professional Project Management and Technology Best Practices To Construction Projects by Contractors September 2019Document195 pagesApplying Professional Project Management and Technology Best Practices To Construction Projects by Contractors September 2019farhanyazdaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Wind Load CalculationDocument105 pagesWind Load CalculationMadusha Galappaththi100% (2)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- 2 Way SlabDocument22 pages2 Way SlabAhmed Al-AmriPas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Unit3 SPDocument15 pagesUnit3 SPProfNDAcharyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Design of Isolated R.C. Footings: 1. GeneralDocument17 pagesDesign of Isolated R.C. Footings: 1. GeneralAtul ShrivastavaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Unit - 4: Design of BeamsDocument27 pagesUnit - 4: Design of BeamsfarhanyazdaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit6 MCNDocument24 pagesUnit6 MCNNithesh ShamPas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Project RAM Detail: Responsibility Assignment Matrix (RAM)Document6 pagesProject RAM Detail: Responsibility Assignment Matrix (RAM)farhanyazdani100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Contractors Customary Duties ResponsibilitiesDocument6 pagesContractors Customary Duties ResponsibilitiesfarhanyazdaniPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Detail Design ChecklistDocument9 pagesDetail Design ChecklistfarhanyazdaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Cost ControlDocument16 pagesCost ControlLai QuocPas encore d'évaluation

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Introduction and Overview For A Bar ChartDocument10 pagesIntroduction and Overview For A Bar ChartfarhanyazdaniPas encore d'évaluation

- CONCURRENCY DELAY - Is A BUT FOR' Analysis The Legal Interpretation PDFDocument13 pagesCONCURRENCY DELAY - Is A BUT FOR' Analysis The Legal Interpretation PDFfarhanyazdaniPas encore d'évaluation

- 5.software Quality MetricsDocument48 pages5.software Quality MetricsAnit KayasthaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Male Female Male Female Male Female Name Name Name Name Name Name Ra NKDocument1 pageMale Female Male Female Male Female Name Name Name Name Name Name Ra NKfarhanyazdaniPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Draft: Project Title: Consultant Design Responsibility Matrix Reference: DateDocument4 pagesDraft: Project Title: Consultant Design Responsibility Matrix Reference: DatefarhanyazdaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Project No. Ewo No. Moc TitleDocument1 pageProject No. Ewo No. Moc TitlefarhanyazdaniPas encore d'évaluation

- MatrixDocument3 pagesMatrixfarhanyazdaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Piping Construction PhaseDocument3 pagesPiping Construction PhasefarhanyazdaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Duration Percent Complete in Primavera P6Document10 pagesDuration Percent Complete in Primavera P6Abu Mehmad Al BouriniPas encore d'évaluation

- Piping Construction PhaseDocument3 pagesPiping Construction PhasefarhanyazdaniPas encore d'évaluation

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- PipingDocument7 pagesPipingfarhanyazdaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Construction - Responsibility and Scope MatrixDocument6 pagesConstruction - Responsibility and Scope Matrixfarhanyazdani100% (1)

- Long Lead ItemDocument2 pagesLong Lead Itemfarhanyazdani100% (2)

- ObjectivesDocument23 pagesObjectivesMohd WadiePas encore d'évaluation

- Asm and Zfs Comparison PresentationDocument19 pagesAsm and Zfs Comparison PresentationNerone2013Pas encore d'évaluation

- What Is .BRD FileDocument4 pagesWhat Is .BRD FilejackPas encore d'évaluation

- Surge XT ManualDocument130 pagesSurge XT ManualSphola Art-ManPas encore d'évaluation

- Windows Update Standalone Installer in WindowsDocument6 pagesWindows Update Standalone Installer in WindowscostpopPas encore d'évaluation

- Aix UnixDocument3 pagesAix UnixBenigno D. AquinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Computer Prep3 First TermDocument35 pagesComputer Prep3 First TermHend Kandeel50% (4)

- MidexamDocument4 pagesMidexamJack PopPas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Dnemtzow Resumejune2015Document2 pagesDnemtzow Resumejune2015api-260555608Pas encore d'évaluation

- Linux MCQ Fot InterviewDocument2 pagesLinux MCQ Fot InterviewHromit ProdigyPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Unwrap OracleDocument59 pagesHow To Unwrap Oraclersulliv1Pas encore d'évaluation

- 16.79-CH16 - Accessing PDFDocument79 pages16.79-CH16 - Accessing PDFRASHMI_HRPas encore d'évaluation

- UNIX II:grep, Awk, Sed: October 30, 2017Document26 pagesUNIX II:grep, Awk, Sed: October 30, 2017rishimahajanPas encore d'évaluation

- Update With The Latest Questions & AnswersDocument1 pageUpdate With The Latest Questions & Answersfrew abebePas encore d'évaluation

- Ingres 0212Document120 pagesIngres 0212gamurphy65Pas encore d'évaluation

- NCE T FaultDataCollectionGuide (RTN)Document15 pagesNCE T FaultDataCollectionGuide (RTN)KSumiteshPas encore d'évaluation

- AmitKishore JAVA IN4 PaymentDocument2 pagesAmitKishore JAVA IN4 PaymentYugendra RPas encore d'évaluation

- How Do I Register Type Libraries, ActiveX Controls, and ActiveX Servers - National InstrumentsDocument2 pagesHow Do I Register Type Libraries, ActiveX Controls, and ActiveX Servers - National InstrumentsPrabish KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- TVL CSS8 Q3 Week 2 Module 3Document12 pagesTVL CSS8 Q3 Week 2 Module 3JT GeronaPas encore d'évaluation

- Java DocumentationDocument4 pagesJava DocumentationAbhinav AroraPas encore d'évaluation

- Abb Mylearning Navigator - Learner Main Manual v1Document135 pagesAbb Mylearning Navigator - Learner Main Manual v1Vimal KanthPas encore d'évaluation

- Upgrade 2900Document26 pagesUpgrade 2900Jean ChristianPas encore d'évaluation

- Razer Game Booster Diagnostics ReportDocument14 pagesRazer Game Booster Diagnostics ReportHamdan PrakosoPas encore d'évaluation

- Nokia n900 Pwnphone ManualDocument9 pagesNokia n900 Pwnphone ManualFer ContoPas encore d'évaluation

- The in Analysis Databases:: ScienceDocument33 pagesThe in Analysis Databases:: Sciencegreeen.pat6918Pas encore d'évaluation

- CASE 3 Maruti Suzuki Business Intelligence and Enterprise Databases CaseDocument5 pagesCASE 3 Maruti Suzuki Business Intelligence and Enterprise Databases CaseArif Sudibp' Rahmanda100% (1)

- Accenture Platform Evaluation Fitting Your Organizational NeedDocument4 pagesAccenture Platform Evaluation Fitting Your Organizational NeedVenkata SundaragiriPas encore d'évaluation

- Drop BoxDocument208 pagesDrop BoxNicoleta LunguPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample Data Into Splunk EnterpriseDocument58 pagesSample Data Into Splunk EnterpriseOkta Jilid IIPas encore d'évaluation

- 61bdbfaee0419 - Cyber Crime by - Shyam Gopal TimsinaDocument30 pages61bdbfaee0419 - Cyber Crime by - Shyam Gopal TimsinaAnuska ThapaPas encore d'évaluation

- ChatGPT Money Machine 2024 - The Ultimate Chatbot Cheat Sheet to Go From Clueless Noob to Prompt Prodigy Fast! Complete AI Beginner’s Course to Catch the GPT Gold Rush Before It Leaves You BehindD'EverandChatGPT Money Machine 2024 - The Ultimate Chatbot Cheat Sheet to Go From Clueless Noob to Prompt Prodigy Fast! Complete AI Beginner’s Course to Catch the GPT Gold Rush Before It Leaves You BehindPas encore d'évaluation

- The Fabric of Civilization: How Textiles Made the WorldD'EverandThe Fabric of Civilization: How Textiles Made the WorldÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (58)

- Highest Duty: My Search for What Really MattersD'EverandHighest Duty: My Search for What Really MattersPas encore d'évaluation

- Hero Found: The Greatest POW Escape of the Vietnam WarD'EverandHero Found: The Greatest POW Escape of the Vietnam WarÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (19)

- Sully: The Untold Story Behind the Miracle on the HudsonD'EverandSully: The Untold Story Behind the Miracle on the HudsonÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (103)

- The End of Craving: Recovering the Lost Wisdom of Eating WellD'EverandThe End of Craving: Recovering the Lost Wisdom of Eating WellÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (81)

- System Error: Where Big Tech Went Wrong and How We Can RebootD'EverandSystem Error: Where Big Tech Went Wrong and How We Can RebootPas encore d'évaluation