Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Freight Transportation and Value Chains

Transféré par

Nashrullah Jamil0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

46 vues9 pagesKapal

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

DOCX, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentKapal

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme DOCX, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

46 vues9 pagesFreight Transportation and Value Chains

Transféré par

Nashrullah JamilKapal

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme DOCX, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 9

Freight Transportation and Value Chains

Author: Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

1. Contemporary Production

Systems Production

and

consumption

are

the

two core

components of economic systems and are both interrelated

through the conventional supply / demand relationship. Basic

economic theory underlines that what is being consumed has to

be produced and what is being produced has to be consumed.

Any disequilibrium between the quantity being produced and the

quantity being consumed can be considered as a market failure.

On one side, insufficient production involves shortages and price

increases, while on the other, overproduction and overcapacity

involves waste, storage and price reductions. It is mainly through

the corporation and its perception of market potential that a set of

decisions are made about how to allocate scarce resources,

reconciling production and consumption.

The realization of production and consumption cannot occur

without flows of freight within a complex system of distribution

that includes, modes, terminals, but also facilities managing

freight activities, namely distribution centers. Contemporary

production systems are the outcome of significant changes in

production factors, distribution and industrial linkages:

Production factors. In the past, the three dominant factors

of production, land, labor and capital, could not be

effectively used at the global level. For instance, a

corporation located in one country had difficulties taking

advantage of cheaper inputs (e.g. labor and land) in another

country, notably because regulations would not permit full

(and often dominant) ownership of a manufacturing facility

by foreign interests. This process has also been

strengthened

by

economic

integration

and

trade

agreements. The European Union established a structure

that facilitates the mobility of production factors, which in

turn enabled a better use of the comparative productivity of

the European territory. Similar processes are occurring in

North America (NAFTA), South America (Mercosur) and in

Pacific-Asia (ASEAN) with various degrees of success. Facing

integration processes and massive movements of capital

coordinated by global financial centers, factors of production

have anextended mobility, which can be global in some

instances. To reduce their production costs, especially labor

costs, many firms have relocated segments (sometimes the

entire process) of their manufacturing activities to new

locations.

Distribution. In the past, the difficulties of overcoming

distances were related to constraints in physical distribution

as well as to telecommunications. Distribution systems had

limited capabilities to ship merchandises between different

parts of the world and it was difficult to manage fragmented

production systems due to inefficient communication

systems. In such a situation, freight alone could cross

borders, while capital flows, especially investment capital,

had more limited ranges. The tendency was to trade finished

goods. Trade could be international, but production systems

were dominantly regionally focused and mainly built

through regional agglomeration economies with industrial

complexes as an outcome. With improvements in

transportation and logistics, the efficiency of distribution has

reached a point where it is possible to manage large scale

production and consumption.

Industrial linkages. In the past, the majority of

relationships between elements of the production system

took place between autonomous entities, which tended to be

smaller in size. As such, those linkages tended to be rather

uncoordinated.

The

emergence

ofmultinational

corporations underlines a higher level of linkages within

production systems, as many activities that previously took

place over several entities are now occurring within the

same corporate entity. While in the 1950s, the share of the

global economic output attributable to multinational

corporations was in the 2% to 4% range, by the early 21st

century this share has surged to a range between 25% and

50%. About 30% of all global trade occurs within elements of

the same corporation, with this share climbing to 50% for

trade between advanced countries.

The development of global transportation and telecommunication

networks, ubiquitous information technologies, the liberalization

of trade and multinational corporations are all factors that have

substantially impacted production systems. Products are getting

increasingly sophisticated requiring a vast array of skills for their

fabrication. One key issue is the array of expansion

strategies available in a global economy, including horizontal and

vertical integration, as well as outsourcing. In many cases, so

called "platform companies" have become new paradigms where

the function of manufacturing has been removed from the core of

corporative activities. Corporations following this strategy,

particularly mass retailers, have been active in taking advantage

of the "China effect" in a number of manufacturing activities.

2. Commodity and Value Chains

Commodities are resources that can be consumed. They can be

accumulated for a period of time (some are perishable while

others can be virtually stored for centuries), exchanged as part of

transactions or purchased on specific markets (such as futures

market). Some commodities are fixed, implying that they cannot

be transferred, except for the title. This includes land, mining,

logging and fishing rights. In this context, the value of a fixed

commodity is derived from the utility and the potential rate of

extraction.

Bulk commodities are commodities that can be transferred, which

includes for instance grains, metals, livestock, oil, cotton, coffee,

sugar and cocoa. Their value is derived from utility, supply and

demand, which is established through major commodity markets

involving a constant price discovery mechanism. The global

economy and its production systems are highly integrated,

interdependent and linked through commodity chains.

Value Chain (also known as commodity chain). A functionally

integrated network of production, trade and service activities that

covers all the stages in a supply chain, from the transformation of

raw materials, through intermediate manufacturing stages, to the

delivery of a finished good to a market. The chain is

conceptualized as a series of nodes, linked by various types of

transactions, such as sales and intrafirm transfers. Each

successive node within a commodity chain involves the

acquisition or organization of inputs for the purpose of added

value.

Value chains are thus a sequential process used by corporations

within a production system togather resources, transform them

in parts and products and, finally, distribute manufactured goods

to markets. Each sequence is unique and dependent on product

types, the nature of production systems, where added value

activities are performed, markets requirements as well as the

current stage of the product life cycle. Value chains enable a

sequencing of inputs and outputs between a range of suppliers

and

customers,

mainly

from

a producer

and

buyerdriven standpoint. They also offer adaptability to changing

conditions, namely an adjustment of production to adapt to

changes in price, quantity and even product specification. The

flexibility of production and distribution becomes particularly

important, with a reduction of production, transaction and

distribution costs as the logical outcome. The three major types of

value chains involve:

Raw materials. The origin of these goods is linked with

environmental (agricultural products) or geological (ores and

fossil fuels) conditions. The flows of raw materials

(particularly ores and crude oil) are dominated by a pattern

where developing countries export towards developed

countries. Transport terminals in developing countries are

specialized in loading while those of developed countries

unload raw materials and often include transformation

activities next to port sites. Industrialization in several

developing countries has modified this standard pattern with

new flows of energy and raw materials.

Semi-finished products. These goods already had some

transformation performed conferring them an added value.

They involve metals, textiles, construction materials and

parts used to make other goods. Depending on the labor

intensiveness and comparative advantages segments of the

manufacturing process have been offshored. The pattern of

exchanges is varied in this domain. For ponderous parts, it is

dominated by regional transport systems integrated to

regional production systems. For lighter and high value

parts, a global system of suppliers tends to prevail.

Manufactured goods. These include goods that are

shipped towards large consumption markets and require a

high level of organization of flows to fulfill the demand. The

majority of these flows concerns developed countries, but a

significant share is related to developing countries,

especially those specializing in export-oriented

manufacturing. Containerization has been the dominant

transport paradigm for manufactured goods with production

systems organized around terminals and their distribution

centers.

3. Integration in Value Chains

Transport chains are being integrated into production

systems. As manufacturers are spreading their production

facilities and assembly plants around the globe to take advantage

of local factors of production, transportation becomes an ever

more important issue. The integrated transport chain is itself

being integrated into the production and distribution processes.

Transport can no longer be considered as a separate service that

is required only as a response to supply and demand conditions. It

has to be built into the entire supply chain system, from multisource procurement, to processing, assembly and final

distribution.

Supply Chain Management (SCM) has become an important facet

of international transportation. As such, the container has become

a transport, production and distribution unit. A significant trend

has thus been a growing level of embeddedness between

production,

distribution

and

market

demand.

Since

interdependencies have replaced relative autonomy and selfsufficiency as the foundation of the economic life of regions and

firms, high levels of freight mobility have become a necessity. The

presence of an efficient distribution system supporting global

value chains (also known as global production networks) is

sustained by:

Functional integration. Its purpose is to link the elements

of the supply chain in a cohesive system of suppliers and

customers. A functional complementarity is then achieved

through a set of supply/demand relationships, implying flows

of freight, capital and information. Functional integration

relies on distribution over vast territories where "just-intime" and "door-to-door" strategies are relevant examples of

interdependencies created by new freight management

strategies. Intermodal activities tend to create heavily used

transshipment points and corridors between them, where

logistical management is more efficient.

Geographical integration. Large resource consumption by

the global economy underlines a reliance on supply sources

that are often distant, as for example crude oil and mineral

products. The need to overcome space is fundamental to

economic development and the development of modern

transport systems have increased the level of integration of

geographically separated regions with a better geographical

complementarity. With improvements in transportation,

geographical separation has become less relevant, as

comparative advantages are exploited in terms of the

distribution capacity of networks and production costs.

Production and consumption can be more spatially

separated without diminishing economies of scale, even if

agglomeration economies are less evident.

The level of customization of a product can also be indicative

about how commodity chains are integrated. For products

requiring a high level of customization (or differentiation) the

preference is usually to locate added value components relatively

close to the final market. For products that can be mass produced

and that require limited customization, the preference leans on

locating where input costs (e.g. labor) are the least.

4. Freight Transport and Value Chains

As the range of production expanded, transport systems adapted

to the new operational realities in local, regional and international

freight distribution. Freight transportation offers a whole spectrum

of services catering to cost, time and reliability priorities and has

consequently taken an increasingly important role within value

chains. Among the most important factors:

Improvements in transport efficiency incited an expanded

territorial range to value chains.

A reduction of telecommunication costs and the

development of information technologies, enabling

corporations to establish a better level of control over

their value chains.Information technologies have a wide

array of impacts on the management of freight distribution

systems.

Technical improvements, notably for intermodal

transportation, enabled a more efficientcontinuity between

different transport modes (especially land / maritime) and

thus within commodity chains.

The results have been an improved velocity of freight, a decrease

of the friction of distance and a spatial segregation of production.

This process is strongly imbedded with the capacity and efficiency

of international and regional transportation systems, especially

maritime and land routes. It is uncommon for the production

stages of a good to occur at the same location.

Consequently, thegeography of value chains is integrated to

the geography of transport systems. Among the main sectors

of integration between transportation and commodity chains are:

Agricultural commodity chains. They include a sequence

of fertilizers and equipment as inputs and cereal, vegetable

and animal production as outputs. Several transportation

modes are used for this production system, including

railcars, trucks and grain ships. Since many food products

are perishable, modes often have to be adapted to these

specific constraints. Agricultural shipments tend to be highly

seasonal with the ebb and flows of harvest seasons. Ports

are playing an important role as points of warehousing and

transshipment of agricultural commodities such as grain. A

growing share of the international transportation of grain is

getting containerized. In 2007, 100 million tons of grain were

carried on bulk ships while an additional 10 million tons was

carried by container. Due to weight limitations, the 20 footer

container appears more suitable as they can handle a full 20

tons load while bigger containers, such as the 40 footer, are

limited to a maximal load of 28 tons.

Energy commodity chains. Include the transport of fuels

(oil, coal, natural gas, etc.) from where they are extracted to

where they are transformed and finally consumed (see for

instance International oil transportation). They are linked to

massive flows of bulk raw materials, notably by railway and

maritime modes, but also by pipeline when possible. They

tend to be very stable and consistent commodity chains

since a constant energy supply is required with some

seasonal variations.

Metal commodity chains. Similar to energy commodity

chains, these systems include the transport of minerals from

extraction sites, but also of metals towards the industrial

sectorsusing them such as shipbuilding, car making,

construction materials, etc.

Chemical commodity chains. Include several branches

such as petrochemicals and fertilizers. This commodity chain

has linkages with the energy and agricultural sectors, since

it is at the same time a customer and a supplier.

Wood and paper commodity chains. Include collection

over vast forest zones, namely Canada, Northern Europe,

South America and Southeast Asia, towards production

centers of pulp and paper and then to consumers.

Construction industry. Implies movements of materials

such as cement, sand, bricks and lumber, many of which are

local in scale.

Manufacturing industry. Involves a much diversified set

of movements of finished and semi-finished goods between

several origins and destinations. These movements will be

related to the level of functional and geographical

specialization of each manufacturing sector. Such flows are

increasingly containerized.

Most value chains are linked to regional transport systems, but

with globalization, international transportation accounts for a

growing share of flows within production systems. The usage of

resources, parts and semi-finished goods by commodity chains

is an indication of the type of freight being transported.

Consequently, transport systems must adapt to answer the

needs of commodity chains, which incites diversification. Within

a commodity chain, freight transport services can be

categorized by:

Management of shipments. Refers to cargo transported

by the owner, the manufacturer or by a third party. The

tendency has been for corporations to sub-contract their

freight operations to specialized providers who provide more

efficient and cost effective services.

Geographical coverage. Implies a wide variety of scales

ranging from intercontinental, within economic blocs,

national, regional or local. Each of these scales often

involves specific modes of transport services and the use of

specific terminals.

Time constraint. Freight services can have a time element

ranging from express, where time is essential, to the lowest

cost possible, where time is secondary. There is also a direct

relationship between transport time and the level of

inventory that has to be maintained in the supply chain. The

shorter the time, the lower the inventory level, which can

result in significant savings.

Consignment size. Depending on the nature of production,

consignments can be carried in full loads, partial loads (less

than truck load; LTL), as general cargo, as container loads or

as parcels.

Cargo type. Unitized cargo (containers, boxes or pallets) or

bulk cargo requires dedicated vehicles, vessels and

transshipment and storage infrastructures.

Mode. Cargo can be carried on a single mode (sea, rail, road

or air) or in a combination of modes through intermodal

transportation.

Cold chain. A temperature controlled supply chain linked to

the material, equipment and procedures used to maintain

specific cargo shipments within an appropriate temperature

range. Commonly relates to the distribution of food and

pharmaceutical products.

Globalization also concomitant a by-product of a post-fordist

environment

where just-in-time(JIT)

and synchronized

flows are becoming the norm in production and distribution

systems. International transportation is shifting to meet the

increasing needs of organizing and managing its flows through

logistics. In spite of the diversity of transport services

supported various value chains, containerization is adaptable

enough to cope with a variety of cargo and time constraints.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Building Management Graha IramaDocument3 pagesBuilding Management Graha IramaNashrullah JamilPas encore d'évaluation

- DNV Rules For PlatingDocument23 pagesDNV Rules For PlatingNashrullah JamilPas encore d'évaluation

- Ship DocumentsDocument18 pagesShip DocumentsNashrullah JamilPas encore d'évaluation

- Freight Distribution ClustersDocument9 pagesFreight Distribution ClustersNashrullah JamilPas encore d'évaluation

- Internal No Beban Luas (m2)Document2 pagesInternal No Beban Luas (m2)Nashrullah JamilPas encore d'évaluation

- Produced by An Autodesk Educational Product: Max DWL Max DWLDocument1 pageProduced by An Autodesk Educational Product: Max DWL Max DWLNashrullah JamilPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- 1.process IntegrationDocument11 pages1.process IntegrationPrem Datt PanditPas encore d'évaluation

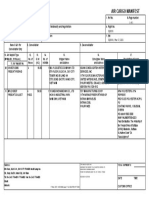

- Air Cargo Manifest: 1 of 1 SQ0191 Singapore Airline (SQ) SQ0191 / Mar 17, 2021 Noibai-Hanoi, VietnamDocument1 pageAir Cargo Manifest: 1 of 1 SQ0191 Singapore Airline (SQ) SQ0191 / Mar 17, 2021 Noibai-Hanoi, VietnamMinh TuanPas encore d'évaluation

- Logistic Field Coordinator - Job DescriptionDocument2 pagesLogistic Field Coordinator - Job Descriptionrisqi sabilalPas encore d'évaluation

- Learning To See - Book SummaryDocument1 pageLearning To See - Book Summarysooraj kutePas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter-2 Role of Logistics in Supply ChainDocument29 pagesChapter-2 Role of Logistics in Supply ChainnidamahPas encore d'évaluation

- Proces CostingDocument14 pagesProces CostingKenDedesPas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture 1 - Introduction To E-Procurement and Related ConceptsDocument19 pagesLecture 1 - Introduction To E-Procurement and Related ConceptsMoney CafePas encore d'évaluation

- Trucking Company List 2021Document16 pagesTrucking Company List 2021Deep RennovatorsPas encore d'évaluation

- Empowering Manufacturing: Generative AI Revolutionizes ERP ApplicationDocument3 pagesEmpowering Manufacturing: Generative AI Revolutionizes ERP ApplicationInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyPas encore d'évaluation

- MCQ Operations ManagementDocument54 pagesMCQ Operations Managementvinayak mishraPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 14Document38 pagesChapter 14Carmelie CumigadPas encore d'évaluation

- Operation Management Quiz 1Document3 pagesOperation Management Quiz 1salmari197480% (5)

- Practice Material On Cost of Goods Manufectured and Sold Statement. MGT402Document34 pagesPractice Material On Cost of Goods Manufectured and Sold Statement. MGT402Syed Ali HaiderPas encore d'évaluation

- Staff Uniform Tracking Spreadsheet - Free TemplateDocument15 pagesStaff Uniform Tracking Spreadsheet - Free TemplateIndustrialsafety IsmailAli60% (5)

- This Study Resource Was: 0business Mathematics BM - LP #05 Lecture Problems: Buying Method First Day Last DayDocument2 pagesThis Study Resource Was: 0business Mathematics BM - LP #05 Lecture Problems: Buying Method First Day Last DayKim FloresPas encore d'évaluation

- 2016 Atlp 6 PDFDocument64 pages2016 Atlp 6 PDFshiwaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Mx-Mex-Dmx: MexicoDocument3 pagesMx-Mex-Dmx: MexicoCPas encore d'évaluation

- Supply Chain Management System of AarongDocument20 pagesSupply Chain Management System of AarongA.Z. MasudPas encore d'évaluation

- Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Marthwada University, AurangabadDocument78 pagesDr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Marthwada University, Aurangabadabhinavk420100% (2)

- FullWork-GilbertNyavieFINALEDITING Aug2014 PDFDocument122 pagesFullWork-GilbertNyavieFINALEDITING Aug2014 PDFAwadhut MaliPas encore d'évaluation

- EDocument65 pagesEDinesh PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- Pr132378ex01 S316620375 BLDocument2 pagesPr132378ex01 S316620375 BLMichelPas encore d'évaluation

- MANTU SLIDE KULIAH 2020 Modul-5Document17 pagesMANTU SLIDE KULIAH 2020 Modul-5Siska AprilianiPas encore d'évaluation

- Gartner Newsletter Amber Road Issue 1 120518 PDFDocument16 pagesGartner Newsletter Amber Road Issue 1 120518 PDFJoseAntonioVallesPas encore d'évaluation

- Production & Materials Management: Course ObjectivesDocument2 pagesProduction & Materials Management: Course ObjectivesAnonymous TX2OckgiZPas encore d'évaluation

- TaskDocument10 pagesTaskFalak HanifPas encore d'évaluation

- "Supply Chain Management of Newspapers": Bachelors of Business Administration (2010-2013)Document44 pages"Supply Chain Management of Newspapers": Bachelors of Business Administration (2010-2013)Shagun ChauhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Incoterm Assignment Question 3.b.Document1 pageIncoterm Assignment Question 3.b.Chirag KawaPas encore d'évaluation

- SAP MM Interview Question 1Document53 pagesSAP MM Interview Question 1Deepak Wagh0% (1)

- Original Doc Grencofe FumiDocument1 pageOriginal Doc Grencofe FumiAndri EzNawanPas encore d'évaluation