Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Flower Lovers Reconsidering The Gardens

Transféré par

Alexandros KastanakisTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Flower Lovers Reconsidering The Gardens

Transféré par

Alexandros KastanakisDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

CENTRO UNIVERSITARIO EUROPEO

PER I BENI CULTURALI

Ravello

STUDIO, TUTELA E FRUIZIONE DEI BENI CULTURALI

THE ARCHAEOLOGY

OF CROP FIELDS AND GARDENS

Proceedings of the 1st Conference

on Crop Fields and Gardens Archaeology

Barcelona (Spain), 1-3 June 2006

edited by

Jean-Paul Morel

Jordi Tresserras Juan and Juan Carlos Matamala

OFF PRINT

Bari 2006

Flower-Lovers? Reconsidering the gardens of Minoan Crete

Jo DAY

Trinity College Dublin

Rsum

Traditionnellement, on a interprt la civilisation de lAge du Bronze dans la Crte dite minoenne comme une

socit paisible qui aimait bien la nature. Des cramiques ornes de fleurs et des fresques pleines de plantes ont

encourag cette ide. De plus, la plupart des prhistoriens ont accept sans se poser de question lhypothse que les

Minoens cultivaient des jardins. Cependant, il ny en avait jusquici aucune preuve. Cet article examine les localits

proposes comme jardins minoens, et les regroupe en deux catgories: des jardins ornant une cour, et des jardins

plus grands qui sont contigus des constructions des lites. De tels jardins, souvent pleins de plantes importes, sont

caractristiques de beaucoup de socits partout dans la Mditerrane antique et jouent des rles importants dans la

diffrenciation sociale. On propose ici une fonction pareille pour les jardins minoens.

In 1900, Sir Arthur Evans began work excavating the Bronze Age site at Knossos in north

central Crete, which would become known to the

world as the Palace of Minos. Named after a

mythological king of the island, this complex

structure was the first in a number of so-called

palaces discovered on Crete throughout the 20th

century. Evans developed a distinctive personal

interpretation of the civilisation which built these

great complexes in the 2nd millennium BC, a

vision which many other excavators followed, and

which still looms over Minoan archaeology (Evans

1921-1935). The inhabitants of Bronze Age Crete

were seen as peaceful, intelligent, sensitive, and

capable of great works of art. The notion

developed that the gentle Minoans led a happy

existence in a world whose characteristics were

the love of life and nature (Platon 1964: 28). It

was their art in particular which fostered such a

belief. Frescoes with scenes of animals and plants,

such as those from room 14 at Ayia Triadha

(Militello and La Rosa 2000) were hugely

influential in developing and reinforcing this idea.

Kamares Ware ceramics of the Protopalatial period

(c.1900-1700 BC) 1 , decorated with intricate

organic motifs, and the more realistic floral

imagery of the Neopalatial pottery (c.1700-1450

BC), combined with the frescoes to present an

image of a society of flower-lovers. This idea of

Minoan flower-lovers is examined here through the

lens of garden archaeology.

For Evans, who himself was a keen amateur

botanist (Brown 2001: vii), it was a certainty that

the Minoans had gardens. He wrote that the rich

burgher class and the Priest Kings themselves

could not have been behindhand in their interior

garden cult (PM III: 277) 2. With his background

in Victorian Britain, where suitable genteel pursuits

included gardening and knowledge of plants, it

seemed to Evans that the cultivation of flowers was

natural for the supposedly peace-loving, artistic

society he had brought to light. It must be noted

however that the gardens that he, and later

excavators, were envisaging, were those belonging

to the upper echelons of society, as opposed to

those used to provide subsistence. Such a focus is

therefore echoed here, concentrating only on

gardens as they relate to a Bronze Age elite.

Claims for garden locations within the palaces,

villas and prosperous towns are re-examined, and

the whole concept of a Minoan garden is

scrutinised.

At Knossos, it has been proposed that a garden

existed in the courtyard outside the Hall of Double

Axes: this was probably a garden terrace,

bounded on the east and south by a low retaining

wall and commanding a view over the valley

beyond (Graham 1987: 87). This part of the

palace has been interpreted as the domestic, or

189

T h e a rc h a e o l o g y o f c ro p f i e l d s a n d g a rd e n s 2 0 0 6 E d i p u g l i a s . r. l . - w w w. e d i p u g l i a . i t

FLOWER-LOVERS? RECONSIDERING THE GARDENS OF MINOAN CRETE

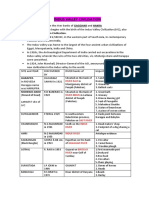

1. - View north across suggested garden at Mallia from within residential quarters (Photo by author).

residential, quarters within the complex. At Mallia,

another palatial site on the north coast of central

Crete, the French excavators suggested a garden

was laid out beyond the so-called residential

quarters in the northwest area (Chapouthier,

Demargne 1962: 37). This area, stretching from

room III.7 to the paved path at the north, appears to

have been left without structures during the

Neopalatial period, or 2nd phase of building, and

so a garden provides a function for this otherwise

unexplained blank space (fig. 1).

Zakros, on the far east coast, is another palatial

site with supposed garden areas. They have been

suggested to have existed on the hill terraces, again

where no traces of structures have been found

(Platon 1985: 255). The excavator noted that the

fertile land to the northeast here would make

cultivation of gardens possible, which must have

added to the attractiveness of the premises and

provided a pleasant resort for members of the royal

family (Platon 1985: 79-80). Another palace, at

Phaistos, near the south coast, also has several

locations for gardens: the unroofed area 49 in the

central North wing, and the southeast corner of the

East wing. Interestingly, Maria Shaw has suggested

a rock garden for this second area (Shaw 1993).

The bedrock outcrop is pitted with holes, in which

she believes the Minoans grew small plants (Shaw

1993: 683) (fig. 2), although not all scholars agree

with this interpretation (e.g. Hitchcock 2000: 173).

Other sites where excavators have envisaged

gardens include Petras, a more recently discovered

palace in east Crete, in an area with no

architectural remains (Tsipopoulou 2003: 47); at

the town of Palaikastro in a space between 2

houses (Shaw 1993: 680); and near the Minoan

villa at Ayia Triadha, again in an unexplained space

(La Rosa 1988: 330). Finally, beside the cistern at

Archanes, Sakellarakis interprets a gathering place

with flowers for Minoans to enjoy (Sakellarakis,

Sapouna-Sakellaraki 1997: 316).

However all these excavators have tended to

shy away from interpretation, and therefore the

type of garden which may have existed in these

locations must be further investigated. Yet before

even attempting interpretation, it is crucial to ask

what is the actual solid evidence for gardens in any

of these areas? The simple answer is none! While

garden archaeology can produce fascinating

results, many of its methods are not applicable in

190

T h e a rc h a e o l o g y o f c ro p f i e l d s a n d g a rd e n s 2 0 0 6 E d i p u g l i a s . r. l . - w w w. e d i p u g l i a . i t

JO DAY

2. - The suggested rock-garden at Phaistos from the east (Photo by author).

the Aegean. The information about the Roman

gardens of Pompeii recovered by Jashemski is

perhaps the most well-known instance of garden

archaeology (Jashemski 1979). Her pioneering

work of taking casts of the cavities remaining in

the hardened volcanic ash allowed the

identification of trees and shrubs once grown there,

as well as illustrating the lay-out of the planting

within the garden. This method is not applicable to

Aegean sites unfortunately, with the exception that

possibly some such practice could be carried out at

Akrotiri, on the island of Thera (Santorini). Buried

by a volcanic eruption during the Late Bronze

Age 3, this site is known as an Aegean Pompeii,

and has revealed plentiful information about life in

the Cyclades during this period.

Other sources of information on gardens

include aerial photography and geophysical survey,

as well as careful excavation which can reveal

differences in soil indicating paths, terraces, and

flower beds (Currie 2005). In the Aegean region,

these methods do not appear to have been

successful, although possibly early identification of

a likely garden area might bring better results. It

must be remembered that to excavate a garden is to

pull apart the very goal of the research, and extra

care must be taken to wring every tiny grain of

information out of the soil, thus potential sites

should be noted as early as possible. Palaeobotany

is the other main source of information on ancient

gardens, and with the constant advances in the

discipline, the potential information which can be

elucidated is ever-increasing. However, without

exploring all the different methods and their

accompanying pros and cons with respect to the

Aegean in detail, suffice it to note that neither

analysis of palaeobotanical remains nor of pollen

has been of any assistance in confirming the

location of a Minoan garden. Naturally, one cannot

help but wonder if the palaces of Knossos or

Mallia, for example, were discovered now rather

than a century ago, whether the more rigorous

methods of current archaeology might further

illuminate this issue.

191

T h e a rc h a e o l o g y o f c ro p f i e l d s a n d g a rd e n s 2 0 0 6 E d i p u g l i a s . r. l . - w w w. e d i p u g l i a . i t

FLOWER-LOVERS? RECONSIDERING THE GARDENS OF MINOAN CRETE

Yet, the search for Bronze Age gardens is not

necessarily a lost cause. The types of areas thus far

suggested for Minoan gardens can be roughly

grouped into two categories. Firstly, a garden has

become a useful explanation for medium-sized

areas which apparently do not have any structures

on them; this applies at Ayia Triadha, Petras,

Palaikastro, Zakros and Mallia. Secondly, gardens

have been suggested for courtyard-type areas,

often beside residential quarters in elite buildings:

Knossos, Phaistos, perhaps Archanes, and Mallia

fits in here too, as well as the courtyards from

other sites where gardens have not been explicitly

claimed. In fact, both these possible types have a

wide variety of comparisons around the

Mediterranean in ancient times, and it is worth

examining these for any light which such analogies

may shed on Minoan gardens.

The courtyard type will be considered first. This

was a small area, forming a bounded unit within

the larger architectural complex, with rooms

leading directly onto to it. This type of garden is,

of course, most familiar from the Roman period,

and the numerous peristyle courtyards excavated at

Pompeii provide a good idea of both the layout and

plants used (Jashemski 1979). It has many

precedents though, such as the courtyard gardens

of Hellenistic monarchs (Nielsen 2001: 177-80).

One such example is the garden in the 3rd Winter

Palace of Herod the Great at Jericho, where a

colonnade surrounded a tree-planted area, and pots

for further plants were sunk into the ground

(Gleason 1993). Various Ptolemies and Seleucids

also had such gardens incorporated into their

palaces. Going further back in time, courtyard

gardens were also found in Egypt. These are often

depicted in tombs, and have a pool in the centre,

which was surrounded by flowers and often trees

too, such as that painted in the tomb of Nebamun

at Thebes (Carroll 2003: fig. 56). Excavations at

the 14 th century BC palace at Amarna have

revealed a courtyard garden here, again with

features like a pool, and flowerbeds (Carroll 2003:

26). All these gardens seem to have had both

official and private functions, for the residents of

the palaces or houses to enjoy, as well as serving as

venues for small official functions and dining.

Turning back to the Minoan evidence, it is

obvious that the courtyards suggested as gardens

are all relatively small and adjacent to the so-called

residential quarters, lack pools, and with the

exception of the Mallia example, are all paved. No

traces of raised soil beds were recovered during

excavations, and so it is suggested here that pot

plants could have been used to create small

gardens in these spaces. Both iconography and

ceramic remains indicate that the Minoans did

indeed grow plants in pots. Flower pot fragments

have been identified at sites such as Zakros (Platon

1985: 255), Knossos (PM III: 277; fig. 186. PM

IV.2: 1002) and Akrotiri (Marinatos 1970: Pl. 51;

Pl. 52.1). These pots have holes in the bottom, an

essential in flower pots to allow drainage and so

prevent the plant getting water-logged. The

difference between these Aegean flower pots and

those well-known from other archaeological sites

is twofold. Firstly, most ancient flower pots tend to

have holes not just in the base, but in the sides too,

to allow the roots room to expand and even break

out of the pot more easily (Carroll 2003: 88-92).

Secondly, the Minoan examples tend to be

decorated while the other ones are plain. Both

these features indicate that Minoan flower pots,

while intended for growing plants in a soil matrix,

were not intended to be sunk into the ground, but

would have remained visible on the surface

wherever they were placed. This, in fact, was

Evanss intuition, and he thought that the larger

light wells and the Central Court at Knossos,

would have held tubs containing plants chosen for

their fragrance or bright colours (PM II: 277-79).

It is important to also consider that flower pots

made of other materials apart from ceramic probably

did exist, but no longer survive. An Amnisos wall

painting hints at larger planters, perhaps made of

wood (Evely 1999: 183), a shape mirrored on the

metal vase of Cretan origin found in Shaft Grave IV

of Grave Circle A at Mycenae (Hood 1994: fig. 150).

Wooden constructions have also been suggested as

containers for trees, possibly to allow transport of the

tree as part of a religious ceremony (Marinatos

1989). The use of vases to hold cut flowers can also

be assumed, and is shown in the fresco from the

window jambs of room 4 in the West House, Akrotiri

(Doumas 1992: fig. 63-64).

The second possible type of Minoan garden is

the larger open space adjacent to elite structures,

and again there are various parallels with other

Mediterranean societies. The civilisations of the

Near East had a long tradition of gardens,

especially ones for the use of royalty and important

guests (Wiseman 1983). These gardens were

192

T h e a rc h a e o l o g y o f c ro p f i e l d s a n d g a rd e n s 2 0 0 6 E d i p u g l i a s . r. l . - w w w. e d i p u g l i a . i t

JO DAY

adjacent to, but not necessarily connected to the

palaces, and were of greater size than courtyard

gardens (Nielsen 2001: 166). They should also be

distinguished from the larger hunting parks, or

pairidaeza, which were found outside the cities

(Carroll 2003:45). King Ashurnasirpal II (883-859

B.C.), for example, planted a royal garden at

Nimrud, with exotic plant (and animal) species,

and canals and waterfalls (Wiseman 1983: 142;

Foster 1998: 323). Surviving reliefs from Room S

of the 7th century North Palace of Ashurbanipal in

Nineveh show scenes of the king and queen in a

garden, surrounded by trees and shrubs, including

grapevines, conifers, date palms, and pomegranates

(Albenda 1976; Albenda 1974). A key element in

these Near Eastern gardens was the range of plants,

and sometimes animals too, with which they were

stocked, enhancing the wondrous nature of an

already impressive project. It should be noted here

that it was not just visually impressive or

decorative plants which were popular, but useful

ones which provided incense, or fruits, and even

fine woods were valued as garden species too.

However, beyond the intriguing blank spaces

introduced above, is there any other evidence such

a garden could have existed in the Aegean Bronze

Age? Certain wall paintings have been interpreted

rather tentatively as perhaps showing tamed rather

than wild landscape, i.e. a park of sorts (Morgan

1988: 92). Both the so-called Nilotic frieze from

Akrotiri (Doumas 1992: figs. 30-34), and the Birds

and Monkeys fresco from the House of the

Frescoes at Knossos (Evely 1999: 247), combine

exotic, perhaps imported animals, and likewise

plants of foreign origin, such as date palms and

papyrus. Similarly, plants from overseas feature in

Minoan ceramic iconography, while flowers of an

Aegean origin appear in Egyptian and Near

Eastern contexts, e.g. the lilies and olive trees

depicted at Tell el-Daba in Egypt (Niemeier,

Niemeier 1998: 80). Could it be suggested that

Minoan elite were no strangers to gardens stocked

with imports, and actively participated in the trade

or exchange of foreign plants?

Rulers of the ancient world, and indeed those of

more recent empires, often made a point of

collecting plants as trophies; for example,

Tuthmoses III ordered the plants that his Majesty

has found in the land of Retenu, i.e. on his Syrian

campaigns, be depicted on the walls at Karnak

(Schwaller de Lubicz 1999: 636). Assyrian

inscriptions tell of the plants Tiglath Pileser I

brought back from his campaigns: I took cedar,

box tree, Kanish oak from the lands over which I

had gained dominion such trees which none

among previous kings, my forefathers, had ever

planted and I planted (them) in the orchards of

my land. I took rare orchard fruit which is not

found in my land (and therewith) filled the

orchards of Assyria (Kuhrt 1995: 310). Botanical

imperialism has long been an expression of power,

and capturing a countrys plant resources can

certainly bring economic gain, such as when the

female pharaoh Hatshepsut successfully

transplanted incense trees from Punt to Egypt. But

anthropological work has shown that acquisition of

exotic things from foreign lands also acts as a

means of social differentiation (Helms 1988).

Those who have the means (material wealth and/or

power to command) to acquire the fruits of

overseas expeditions, in this case plants in

particular, are demonstrating their status by

creating and controlling a garden of marvels. This

is the policy which led to the grand gardens of

Versailles, or those of English landed gentry.

Moreover, if the plants therein have some special

value or symbolism in their country of origin,

possessing them can further enhance the new

owners status. Visitors invited to the garden absorb

these underlying messages on two levels: both an

admiration of the plants themselves as stimulating

to the senses, and at a deeper level of interest or

awe as to where they come from, how the owner

acquired them and maintains them and so on.

Although at first glance the actual evidence for

Minoan gardens seems somewhat lacking,

especially in comparison with other ancient

Mediterranean societies, this does not prevent

certain tentative conclusions being reached. It is

important to underline however, that the use of

analogy does not provide any proof of these

missing Aegean gardens. Just because gardens

were an inextricable part of life for other elites in

different Mediterranean societies, and at different

periods, it does not mean that the Minoans must

have had them too. (It must be added though that the

Minoans would be a practically unique society if

some form of gardens were not a feature of their

civilisation). Crucially, analogies can function as

springboards for new ideas, and used here in tandem

with the archaeological evidence, have led to new

theories about Bronze Age gardens in the Aegean.

193

T h e a rc h a e o l o g y o f c ro p f i e l d s a n d g a rd e n s 2 0 0 6 E d i p u g l i a s . r. l . - w w w. e d i p u g l i a . i t

FLOWER-LOVERS? RECONSIDERING THE GARDENS OF MINOAN CRETE

The open spaces which may once have been the

locations for gardens do exist amongst the ruins of

former elite buildings. Iconography also holds

enough tantalising hints to make it relatively likely

that the Minoans tended certain plants for reasons

beyond subsistence. Furthermore the connections

between Egypt, the Near East and the Aegean do

allow for the spread of ideas across cultures

(Davies, Schofield 1995). Most importantly, rather

than envisaging mere decorative flower gardens, as

some scholars have done (Schfer 1992), it should

be considered that Minoan gardens could contain

all kinds of plants, shrubs and trees, with a variety

of uses and meanings. Certainly, the idea that

gardens are yet another form of display and social

differentiation is in accord with the stratified

society which existed in Neopalatial Crete.

Whether they also had some form of religious

function, as with many Egyptian gardens, remains

unclear. For the future, one can hold out hope that

a garden may be discovered at Akrotiri, and that

very careful excavation of open spaces in elite

structures may reveal palaeobotanical traces.

Finally, it is important to consider that the Minoans

may have been flower lovers not just because of

some gentle interest in the natural world, but

because, like other luxury products, plants and

gardens were yet another expression of elite power

around the Mediterranean during the Bronze Age 4.

Notes

Dates following Dickinson 1994.

PM is the standard abbreviation for Evans 1921-1935.

Roman numerals refer to volume number.

3

The date for the eruption is a much-debated matter, and no

consensus has been reached. See Manning 1999 for discussion

of the issue.

4

I would like to thank Trinity Trust Travel Grant Award

Scheme for providing financial support for research trips to

Crete; Heinrich Hall for assistance on those Cretan trips; the

Department of Classics in Trinity College Dublin for financial

assistance to attend the conference in Barcelona; and

Rosemary Day for aid with French translation.

1

2

Bibliography

Albenda 1974: P. Albenda - Grapevines in Ashurbanipals garden, in Bulletin of the American

Schools of Oriental Research, 215, 1974, p. 517.

Albenda 1976: P. Albenda - Landscape bas-reliefs

in the Bit-Hilani of Ashurbanipal, in Bulletin

of the American Schools of Oriental Research,

224, 1976, p. 49-72.

Brown 2001: A. Brown - Arthur Evanss Travels in

Crete 1894-1899, Oxford, Archaeopress, 2001

(BAR Int. Ser. 1000).

Carroll 2003: M. Carroll - Earthly Paradises,

London, British Museum Press, 2003.

Chapouthier, Demargne 1962: F. Chapouthier, P.

Demargne - Mallia. Quatrime Rapport (19271935 et 1946-1960), Paris, Librairie Orientaliste

Paul Geuthner, 1962 (tudes Crtoises XII).

Currie 2005: C. Currie - Garden Archaeology. A

Handbook, York, Council for British Archaeology, 2005 (Practical Handbooks in Archaeology, No. 17).

Davies, Schofield 1995: W. Davies, L. Schofield

(Eds.) - Egypt, the Aegean and the Levant.

Interconnections in the Second Millennium

B.C., London, British Museum Press, 1995.

Dickinson 1994: O. Dickinson - The Aegean

Bronze Age, Cambridge, Cambridge University

Press, 1994.

Doumas 1992: C. Doumas - The Wall Paintings of

Thera, Athens, The Thera Foundation, 1992.

Evans 1921-1935: A.-J. Evans - The Palace of

Minos at Knossos, 4 vols., London, MacMillan

and Co., 1921-1935.

Evely 1999: D. Evely Fresco: A Passport into

the Past. Minoan Crete Through the Eyes of

Mark Cameron, Athens, British School at

Athens, 1999.

Foster 1998: K. Polinger Foster - Gardens of

Eden: exotic flora and fauna in the ancient

Near East, in Yale Forestry and Environmental

Studies Bulletin 103, 1998, p. 320-329.

Gleason 1993: K. Gleason A garden excavation

in the oasis palace of Herod the Great at

Jericho, in Landscape Journal, 12 (2), 1993, p.

156-167.

Graham 1987: J.W. Graham The Palaces of

Crete, 2nd ed., Princeton, Princeton University

Press, 1987.

Helms 1988: M. Helms - Ulysses Sail: An

Ethnographic Odyssey of Power, Knowledge,

and Geographical Distance, Princeton,

Princeton University Press, 1988.

Hitchcock 2000: L. Hitchcock - Minoan

Architecture. A Contextual Analysis, Jonsered,

Paul strms Frlag, 2000.

Hood 1994: S. Hood - The Arts in Prehistoric

Greece, New Haven and London, Yale

University Press, 1994.

Jashemski 1979: W. Jashemski - The Gardens of

Pompeii, Herculaneum, and the Villas

194

T h e a rc h a e o l o g y o f c ro p f i e l d s a n d g a rd e n s 2 0 0 6 E d i p u g l i a s . r. l . - w w w. e d i p u g l i a . i t

JO DAY

Destroyed by Vesuvius, New York, Caratzas

Brothers, 1979.

Kuhrt 1995: A. Kuhrt - The Ancient Near East,

London and New York, Routledge, 1995.

La Rosa 1988: V. La Rosa - Ayia Triada, in Kritiki

Estia 2, 1988, p. 329-330.

Manning 1999: S. Manning - A Test of Time,

Oxford, Oxbow, 1999.

Marinatos 1970: S. Marinatos Excavations at

Thera III, Athens, Bibliothiki tis en Athinais

Archaiologikis Etaireias, 1970.

Marinatos 1989: N. Marinatos - The tree as a

focus of ritual action in Minoan glyptic art, in

Fragen und Probleme der Bronzezeitlichen

gischen Glyptik. Beitrge zum 3. Internationalen Marburger Siegel-Symposium, 5-7

September 1985, Berlin, Mann, 1989, p. 127142.

Militello, La Rosa 2000: P. Militello, V. La Rosa New data on fresco painting from Ayia Triada,

in The Wall Paintings of Thera. Proceedings of

the First International Symposium. Thera,

1997, Athens, Thera Foundation, 2000, p. 991997.

Morgan 1988: L. Morgan The Miniature Wall

Paintings of Thera, Cambridge, Cambridge

University Press, 1988.

Nielsen 2001: I. Nielsen - The gardens of the

Hellenistic palaces, in The Royal Palace

Institution in the First Millenium BC.

Regional Development and Cultural

Interchange between East and West, Athens,

1999, Athens, The Danish Institute at Athens,

2001 (Monographs of the Danish Institute at

Athens 4).

Niemeier, Niemeier 1998: W.-D. and B. Niemeier

- Minoan frescoes in the eastern Mediterranean, in The Aegean and the Orient in the

Second Millennium: Proceedings of the 50th

Anniversary Symposium, Cincinnati, 18-20

April 1997. Aegaeum 18, Lige, Universit de

Lige, Austin, University of Texas at Austin,

1998, p. 69-99.

Platon 1964: N. Platon - A Guide to the

Archaeological Museum of Heraklion, 5th ed.,

Athens, Department of Antiquities and

Restorations, 1964.

Platon 1985: N. Platon - Zakros, Amsterdam,

Adolf M. Hakkert, 1985.

Sakellarakis, Sapouna-Sakellaraki 1997: Y.

Sakellarakis, E. Sapouna-Sakellaraki Archanes. Minoan Crete in a New Light,

Athens, Ammos Publications, 1997.

Schfer 1992: J. Schfer - The role of gardens in

Minoan civilisation, in The Civilizations of the

Aegean and their Diffusion in Cyprus and the

Eastern Mediterranean, 2000 - 600 B.C.

Proceedings of an International Symposium,

Larnaca, 18-24 September 1989, Larnaca,

Pierides Foundation, 1992, p. 84-87.

Schwaller de Lubicz 1999: R. Schwaller de

Lubicz - The Temples of Karnak, London,

Thames and Hudson, 1999.

Shaw 1993: M.C. Shaw - The Aegean garden, in

American Journal of Archaeology 97, 1993, p.

661-685.

Tsipopoulou 2003: M. Tsipopoulou - The Minoan

palace at Petras, Siteia (Eastern Crete), in

Athena Review, 3 (3), 2003, p. 44-51.

Wiseman 1983: D. Wiseman - Mesopotamian

Gardens, in Anatolian Studies, 33, 1983, p.

137-144.

195

T h e a rc h a e o l o g y o f c ro p f i e l d s a n d g a rd e n s 2 0 0 6 E d i p u g l i a s . r. l . - w w w. e d i p u g l i a . i t

T h e a rc h a e o l o g y o f c ro p f i e l d s a n d g a rd e n s 2 0 0 6 E d i p u g l i a s . r. l . - w w w. e d i p u g l i a . i t

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Between Protopalatial Houses and NeopalaDocument33 pagesBetween Protopalatial Houses and NeopalaAlexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- Social Production of SpaceDocument26 pagesSocial Production of SpaceAlexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- Prostitute Nun or Man-Woman Revisiting T PDFDocument28 pagesProstitute Nun or Man-Woman Revisiting T PDFAlexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- Diachronic Changes in Minoan Cave CultDocument16 pagesDiachronic Changes in Minoan Cave CultAlexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- Panagiotopoulos Minoan Zominthos 2006Document29 pagesPanagiotopoulos Minoan Zominthos 2006Alexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- A New InterpretationDocument6 pagesA New InterpretationAlexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- Strasser Th. Panagopoulou E. Runnels C PDFDocument48 pagesStrasser Th. Panagopoulou E. Runnels C PDFAlexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- Double AxeDocument21 pagesDouble AxeAlexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- Central Places and Major Roads in The Pe PDFDocument30 pagesCentral Places and Major Roads in The Pe PDFAlexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- Central Places and Major Roads in The Pe PDFDocument30 pagesCentral Places and Major Roads in The Pe PDFAlexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender Based ArchaeologyDocument19 pagesGender Based ArchaeologynancyshmancyPas encore d'évaluation

- Before The CretansDocument12 pagesBefore The CretansAlexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- 01-Angelos Papadopoulos PDFDocument18 pages01-Angelos Papadopoulos PDFAlexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- Cadogan 2017 Myrtos-PyrgosDocument55 pagesCadogan 2017 Myrtos-PyrgosAlexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- (Argyro Tataki (Τατάκη, Αργυρώ) ) Maced PDFDocument586 pages(Argyro Tataki (Τατάκη, Αργυρώ) ) Maced PDFAlexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- MM Burial Customs at Knossos The Mavro SDocument13 pagesMM Burial Customs at Knossos The Mavro SAlexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- I Am TyrannosaurusDocument17 pagesI Am TyrannosaurusAlexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- The Role of Royal Women in Minoan SocietyDocument31 pagesThe Role of Royal Women in Minoan SocietyAlexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- The Late Minoan II - IIIA1 Warrior Graves PDFDocument11 pagesThe Late Minoan II - IIIA1 Warrior Graves PDFAlexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- Italian Study Guide PDFDocument32 pagesItalian Study Guide PDFPayam TamehPas encore d'évaluation

- Curta 2013Document47 pagesCurta 2013Alexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- Kathleen Mccleary House and HomeDocument270 pagesKathleen Mccleary House and HomeAlexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- Archaeological and Inscriptional Evidence For Phoenician Astarte in D Sugimoto Ed Transformation of A Goddess LibreDocument42 pagesArchaeological and Inscriptional Evidence For Phoenician Astarte in D Sugimoto Ed Transformation of A Goddess LibreAlexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- WalkerDocument13 pagesWalkerAlexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- An Interview With Amos Rapoport On Vernacular Architecture: Creperie Bretonne Lou Vain La Neuve Belgium JULY 13,1979Document14 pagesAn Interview With Amos Rapoport On Vernacular Architecture: Creperie Bretonne Lou Vain La Neuve Belgium JULY 13,1979Alexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- ARxxA Eg 01 07Document4 pagesARxxA Eg 01 07Alexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- E Idd AsherahDocument9 pagesE Idd AsherahAlexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- World MedalsDocument33 pagesWorld MedalsAlexandros Kastanakis100% (1)

- 1 Karag-PpDocument6 pages1 Karag-PpAlexandros KastanakisPas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5782)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- On TyrannyDocument8 pagesOn TyrannyNeni PanourgiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Archaeology Meets CriminologyDocument16 pagesArchaeology Meets Criminologykh17Pas encore d'évaluation

- Class 11 English Project 'The Valley of Kings'Document22 pagesClass 11 English Project 'The Valley of Kings'Arjun RatanPas encore d'évaluation

- Animal Sacrifice and Feasting in Celtic PDFDocument242 pagesAnimal Sacrifice and Feasting in Celtic PDFFederico MisirocchiPas encore d'évaluation

- Indus Valley Civilisation: HarappaDocument14 pagesIndus Valley Civilisation: HarappaSatyaReddyPas encore d'évaluation

- Kalani History A Leap of FaithDocument51 pagesKalani History A Leap of FaithMichael HeidbrinkPas encore d'évaluation

- The Phantom of Classicism in Greek Architecture: Dimitris PhilippidesDocument8 pagesThe Phantom of Classicism in Greek Architecture: Dimitris PhilippidesIsabel Llanos ChaparroPas encore d'évaluation

- Wales Ten TribesDocument17 pagesWales Ten Tribesgregor_damir2519100% (2)

- Sourcebook Table of ContentsDocument7 pagesSourcebook Table of ContentsAivars SiliņšPas encore d'évaluation

- Coggins Toltec 2002Document52 pagesCoggins Toltec 2002Hans Martz de la VegaPas encore d'évaluation

- Kingdomofkush StudentsworksheetsDocument12 pagesKingdomofkush StudentsworksheetsBradford OhblivPas encore d'évaluation

- Greek Temples OrientationDocument5 pagesGreek Temples OrientationpepepartaolaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Greeks and Their Neighbors 10 Week PDFDocument7 pagesThe Greeks and Their Neighbors 10 Week PDFDaniel Stain FerreiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Important Summary Notices: Please NoteDocument37 pagesImportant Summary Notices: Please NotegrgaprgaPas encore d'évaluation

- (Historical Dictionaries of Ancient Civilizations and Historical Eras volume 10) Richard A., Jr. Lobban - Historical Dictionary of Ancient and Medieval Nubia (Historical Dictionaries of Ancient Civili.pdfDocument585 pages(Historical Dictionaries of Ancient Civilizations and Historical Eras volume 10) Richard A., Jr. Lobban - Historical Dictionary of Ancient and Medieval Nubia (Historical Dictionaries of Ancient Civili.pdfAhmed Almukhtar100% (2)

- A Visit To Shiv Gunga Temple MalkanaDocument3 pagesA Visit To Shiv Gunga Temple MalkanaShahid AzadPas encore d'évaluation

- Comb MvbfbakingDocument12 pagesComb MvbfbakingCallum CurninPas encore d'évaluation

- A Prehistory of The NorthDocument246 pagesA Prehistory of The NorthBianca Niculae100% (7)

- Visiting the Great Pyramid of GizaDocument4 pagesVisiting the Great Pyramid of Gizayenny valencia100% (1)

- Biographies of Things: Anthony HardingDocument6 pagesBiographies of Things: Anthony HardingVaniaMontgomeryPas encore d'évaluation

- On Site Digital Archaeology - GIS-based Excavation Recording in Southern JordanDocument12 pagesOn Site Digital Archaeology - GIS-based Excavation Recording in Southern JordanAntonio ManhardPas encore d'évaluation

- PhoeniciansDocument3 pagesPhoeniciansAngela MaldonadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding Culture, Society and Politics Human Capacity For Culture Module-4Document4 pagesUnderstanding Culture, Society and Politics Human Capacity For Culture Module-4Stephanie Dillo100% (2)

- Zandee - Death As An Enemy PDFDocument182 pagesZandee - Death As An Enemy PDFImhotep72100% (5)

- India and The WorldDocument164 pagesIndia and The WorldIndia History Resources100% (4)

- New Rock Art Discoveries in Kurnool DistrictDocument16 pagesNew Rock Art Discoveries in Kurnool Districtkmanjunath7Pas encore d'évaluation

- Arturo Sangalli-Pythagoras' Revenge - A Mathematical Mystery-Princeton University Press (2009)Document301 pagesArturo Sangalli-Pythagoras' Revenge - A Mathematical Mystery-Princeton University Press (2009)Mónica MondragónPas encore d'évaluation

- Written Report - BOOC, LOVELY A.Document9 pagesWritten Report - BOOC, LOVELY A.Lovely Aballe BoocPas encore d'évaluation

- History of FranceDocument496 pagesHistory of FrancevPas encore d'évaluation

- Adobe Bricks Reveal Labor Changes in Ancient PeruDocument39 pagesAdobe Bricks Reveal Labor Changes in Ancient PerutsamalciumPas encore d'évaluation