Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Freedom of Speech and Expression India and United States

Transféré par

Aarif Mohammad BilgramiTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Freedom of Speech and Expression India and United States

Transféré par

Aarif Mohammad BilgramiDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

2015

Jamia

Millia

Islamia

UNIVERSI

TY

SUBMITTED TO

Mr.

FACULTY OF LAW

SUBMITTED BYAarif Mohammad

Bilgrami

I SEM

COMPARITIVE CONSTITUTION

COMPARITIVE CONSTITUTION

Introduction

Where there is a right, there is a duty. The duties against the right to freedom of speech and expression are

enshrined within the Constitution of India in the form of restrictions under Article 19(2). While it is

necessary to maintain and preserve the freedom of speech and expression in a democracy, so also it is

[COMPARITIVE CONSTITUTION]

TOPIC

RESTRICTION ON FREEDOM OF

SPEECH & EXPRESSION:INDIA & U.S

necessary to place some curbs on this freedom for the maintenance of social order. Hence, no freedom can

be absolute or completely unrestricted.1

REASONABLE RESTRICTIONS: ARTICLES 19(2) TO 19(6)

Article 19(2) to 19(6) generally contain limitations on the six rights guaranteed under Article 19(1).

The legislature cannot restrict these freedoms beyond the requirements of Articles 19(2) to 19(6).

These limitations are characterised by the following noteworthy points::

(1) The restrictions can be imposed only by or under the authority of a law; no restriction can be

imposed by Executive action alone without there being a law to back it up.

(2) Each restriction must be reasonable.

(3) A restriction must be related to the purposes mentioned in Clauses 19(2) to 19(6).

GROUNDS OF RESTRICTIONS

Sovereignty And Integrity Of India

1 Ramlila Maidan Incident v. Home Secretary, Union of India (2012) 2 MLJ 32 (SC), wherein

the Court observed that the right that springs from Article 19(1)(a) is not absolute and

unchecked. There cannot be any liberty absolute in nature and uncontrolled in operation so

as to confer a right wholly free from any restraint. Also see, Sahara Real Estate Corpn. Ltd.

v. Securities and Exchange Board of India, AIR 2012 SC 3829.

COMPARITIVE CONSTITUTION

Section 2 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1961, makes penal the questioning of the territorial

integrity of frontiers of India in a manner which is, or is likely to be, prejudicial to the interests of the

safety or security of India.

Security Of State And Public Order

Article 19 (2) uses two concepts; public order and security of the state - the former being wider in its

ramifications than the latter. As the Supreme Court rightly points out, in Article 19(2), there exist two

expressions public order and security of the state.

The term public order covers a small riot, an affray, breaches of peace, or acts disturbing public

tranquillity. But public order and public tranquillity may not always be synonymous. For example, a

man playing loud music in his home at night may disturb public tranquillity, but not public order.

In Kishori Mohan Bera vs. State of West Bengal,2 the Supreme Court explained the differences between

three concepts: law and order, public order, security of State. Anything that disturbs public peace or

public tranquility disturbs public order.3 But mere criticism of the government does not necessarily

disturb public order.4

An aggravated form of disturbance of peace, which threatens the foundations of, or threatens to

overthrow, the state will fall within the scope of the phrase security of state. The expression

overthrowing the state is covered by the term security of state.

Friendly Relations With Foreign States

This ground was added by the Constitution (First Amendment) Act of 1951. The objective behind

imposing restrictions on the freedom of speech in the interests of friendly relations with a foreign country

is that persistent and malicious propaganda against a foreign power having friendly relations with India

may cause considerable embarrassment to India, and, accordingly, indulging in such a propaganda may be

prohibited.

Under Article 367(3), a foreign State means any State other than India. The President, however, may,

subject to any law made by Parliament, by order declare any State not to be a foreign State for such

purposes as may be specified in the order. The Constitution (Declaration as to Foreign State) Order, 1950,

directs that a Commonwealth country is not to be a foreign State for the purposes of the Constitution.

. The Supreme Court has stated in Jagan Nath v. Union of India5 that a country may not be regarded as a

foreign State for the purposes of the Constitution, but may be regarded as a foreign power for other

purposes.

2 AIR 1972 SC 1749.

3 Om Prakash v. Emperor, AIR 1948 Nag 199.

4 Raj Bahadur Gond v. State of Hyderabad, AIR 1953 Hyd 277.

5 AIR 1960 SC 675.

COMPARITIVE CONSTITUTION

Decency Or Morality

The terms decency and morality carry variable meanings in variable societies depending on the

standards of morals prevailing at a constant time period in the contemporary society.

The Indian Penal Code in Sections 292 to 294 lists some of the offences, like selling obscene books,

selling obscene things to young persons, committing an obscene act, or singing an obscene song in a

public place. Section 292 I.P.C. has been held valid because the law against obscenity seeks no more than

to promote public decency and morality.6

On the question of obscenity, the Court has laid emphasis on the importance of art to a value judgement

by the censors. Art should be preserved and promoted in any scheme of censorship for, as the Court

observed.

Contempt Of Court

The Constitution specifically empowers both the Supreme Court7 as well as each High Court8 to punish its

contempt. The freedom of speech and expression guaranteed by Article 19(1)(a) is thus subject to Articles

19(2), 129 and 215.

In addition to the Supreme Court and High Courts, the contempt of other Courts can be punished by the

High Courts under the Contempt of Courts Act, 1952. Section 228, I.P.C., also makes some cases of

contempt of Court punishable.

Charging the judiciary as an instrument of oppression, and the judges as guided and dominated by

class hatred instinctively favouring the rich against the poor has been held to constitute contempt of

Court.

Defamation

Defamation is both a crime as well as a tort. According to Winfield, Defamation is the publication of a

statement which reflects on a persons reputation and tends to lower him in the estimation of rightthinking members of society generally or tends to make them shun or avoid him. 9 As a crime,

Defamation is defined in Section 49 I.P.C. The law seeks to protect a person in his reputation as in his

person or property.

Incitement To An Offence

6 Ranjit Udeshi v. State of Maharashtra, AIR 1965 SC 881.

7 Article 129.

8 Article 215.

9 Winfield and Jolowicz on Tort, 274 (1979).

COMPARITIVE CONSTITUTION

According to the general theories of criminal law, incitement and abetment of a crime is punishable.

Incitement to serious and aggravated offences, like murder, may be punished as involving the security of

the State.10 Incitement to many other offences may be made punishable as affecting the public order. But

there may still be some offences like bribery, forgery, cheating, etc., having no public order aspect, and

incitement to which could not be made punishable as an aspect of public order. So Article 19(2) has the

words incitement to an offence.

The word offence has not been defined in the Constitution but according to the General Clauses Act, it

means any act or omission made punishable by law.

HATE SPEECH

The Constitution of India and its hate speech laws aim to prevent discord among its many ethnic and

religious communities. The laws allow a citizen to seek the punishment of anyone who shows the citizen

disrespect "on grounds of religion, race, place of birth, residence, language, caste or community or any

other ground whatsoever". The laws specifically forbid anyone from outraging someone's "religious

feelings".

This law has often been criticised for being misused by individuals, people or groups for simply censoring

or trying to censor conflicting point of views raised by another individual, people or groups irrespective

of their objective merits,

India prohibits hate speech by several sections of the Indian Penal Code, the Code of Criminal Procedure,

and by other laws which put limitations on the freedom of expression. Section 95 of the Code of Criminal

Procedure gives the government the right to declare certain publications forfeited if the publication ...

appears to the State Government to contain any matter the publication of which is punishable under

Section 124A or Section 153A or Section 153B or Section 292 or Section 293 or Section 295A of the

Indian Penal Code. An apex court bench headed by the then Chief Justice Altamas Kabir issued the

notice after senior counsel Basva Patil told the court that such leaders deliver hate speeches repeatedly,

inflaming regional, religious and ethnic passion.

"We cannot curtail fundamental rights of people. It is a precious rights guaranteed by Constitution," a

bench headed by Justice RM Lodha said, adding "we are a mature democracy and it is for the public to

decide. We are 1280 million people and there would be 1280 million views. One is free not accept the

view of others". Also the court said that it is a matter of perception, and a statement objectionable to a

person might not be normal to other person.11

RESTRICTIONS IN THE U.S.

10 State of Bihar v. Shailabala Devi, AIR 1952 SC 329.

11 Ibid.

COMPARITIVE CONSTITUTION

The Supreme Court has identified categories of speech that are unprotected by the First Amendment and

may be prohibited entirely. Among them are obscenity, child pornography, and speech that constitutes socalled fighting words or true threats. In a 2010 case, the Court made clear that it would not be likely

to add more categories to the list of types of speech that currently fall outside the First Amendments

purview, but it did not entirely rule out the possibility that other forms of unprotected speech exist12.

Incitement

The Supreme Court has held that "advocacy of the use of force" is unprotected when it is "directed to

inciting or producing imminent lawless action" and is "likely to incite or produce such action". 13 In

Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), the Court struck down a criminal conviction of a Ku Klux Klan group for

"advocating ... violence ... as a means of accomplishing political reform" because their statements at a

rally did not express an immediate, or imminent intent to do violence.

False statements of fact

In Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc. (1974), the Supreme Court decided that there is "no constitutional value

in false statements of fact"14.

The Supreme Court has established a complex framework in determining which types of false statements

are unprotected. There are four such areas which the Court has been explicit about. First, false statements

of fact that are said with a "sufficiently culpable mental state" can be subject to civil or criminal liability.

Secondly, knowingly making a false statement of fact can almost always be punished. For example, libel

and slander law are permitted under this category. Third, negligently false statements of fact may lead to

civil liability in some instances.15 Additionally, some implicit statements of factthose that may just have

a "false factual connotation"still could fall under this exception16.

There is also a fifth category of analysis. It is possible that some completely false statements could be

entirely free from punishment. The Supreme Court held in the landmark case New York Times v.

12 U.S. v. Stevens, 559 U.S. 460 (2010) (Maybe there are some categories of speech that

have been historically unprotected, but have not yet been specifically identified or

discussed as such in our case law. But if so, there is no evidence that depictions of animal

cruelty is among them. We need not foreclose the future recognition of such additional

categories to reject the Government's highly manipulable balancing test as a means of

identifying them.)

13 Brandenburg v. Ohio

14 Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc., 418 U.S. 323 (1974).

15Dun & Bradstreet v. Greenmoss Builders, 472 U.S. 749 (1985).

16 Milkovich v. Lorain Journal Co., 497 U.S. 1 (1990).

COMPARITIVE CONSTITUTION

Sullivan (1964) that lies about the government may be protected completely. However, this category is

not entirely clear, as the question of whether false historical or medical claims are protected is still

disputed.

Obscenity

Under the Miller test (which takes its name from Miller v. California, 1973), speech is unprotected if (1)

"the average person, applying contemporary community standards, would find that the [subject or work in

question], taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest" and (2) "depicts or describes, in a patently

offensive way, contemporary community standards17, sexual conduct defined by the applicable state law"

and (3) "the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value". Some

subsidiary components of this rule may permit private possession of obscene materials at one's home 18.

Additionally, the phrase "appeals to the prurient interest" is limited to appeals to a "shameful or morbid

interest in sex"19

Fighting Words and True Threats

So-called fighting words also lay beyond the pale of First Amendment protection. 20 The fighting

words doctrine began in Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, where the Court held that fighting words, by

their very utterance, inflict injury and tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace and thus may be

punished consistent with the First Amendment. 21 In Chaplinsky, the Court upheld a statute which

prohibited a person from addressing any offensive, derisive or annoying word to any other person who is

lawfully in any street or other public place, calling him by any offensive or derisive name, or making

any noise or exclamation in his presence and hearing with the intent to deride, offend or annoy him, or to

prevent him from pursuing his lawful business or occupation.22

17 Smith v. United States, 431 U.S. 291 (1977).

18 Stanley v. Georgia, 394 U.S. 557 (1969).

19 Brockett v. Spokane Arcades, Inc., 472 U.S. 491 (1985).

20 Virginia v. Black, 538 U.S. 343, 363 (2003)(finding that cross-burning is a particularly

virulent form of intimidation that may be punished as a true threat).

21 Chaplinskyv. New Hampshire 315 U.S. at 572.

22

COMPARITIVE CONSTITUTION

This category of proscribable speech requires the threat of an immediate breach of peace in order to be

punishable. In Cohen v. California, the Supreme Court held that words on a t-shirt that contained an

expletive were not directed at a person in particular and could not be said to incite an immediate breach of

the peace.

Child Pornography

Child pornography is material that visually depicts sexual conduct by children. 23 It is unprotected by the

First Amendment even when it is not obscene; that is, child pornography need not meet the Miller test to

be banned. Because of the legislative interest in destroying the market for the exploitative use of children,

there is no constitutional right to possess child pornography even in the privacy of ones own home.24

In 1996, Congress enacted the Child Pornography Protection Act (CPPA), which defined child

pornography to include visual depictions that appear to be of a minor, even if no minor is actually used.

The Supreme Court, however, declared the CPPA unconstitutional to the extent that it prohibited pictures

that are produced without actual minors.25

Intellectual Property Rights

Another class of permissible restrictions on speech are based on intellectual property rights. Things like

copyrights or trademarks fall under this exception. The Supreme Court first held this in Harper & Row v.

Nation Enterprises26, where copyright law was upheld against a First Amendment free speech challenge.

Also, broadcasting rights for shows are not an infringement of free speech rights. 27 The Court has upheld

such restrictions as an incentive for artists in the 'speech marketplace'.

Commercial speech

While there is no complete exception, legal advocates recognize it as having "diminished protection". For

example, false advertising can be punished and misleading advertising may be prohibited. 28 Commercial

23 New York v. Ferber, 458 U.S. 747, 764 (1982). The definition of sexually explicit

conduct in the federal child pornography statute includes lascivious exhibition of the

genitals or pubic area of any person [under 18], and is not limited to nude exhibitions or

exhibitions in which the outlines of those areas [are] discernible through clothing.

24 Osborne v. Ohio, 495 U.S. 103 (1990).

25 Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition, 435 U.S. 234 (2002).

26 471 U.S. 549 (1985).

27 Zacchini v. Scripps-Howard Broadcasting Co., 433 U.S. 562 (1977).

28 Peel v. Attorney Reg. & Discip. Comm'n, 496 U.S. 91 (1990).

COMPARITIVE CONSTITUTION

advertising may be restricted in ways that other speech can't if a substantial governmental interest is

advanced, and that restriction supports that interest as well as not being overly broad. 29 This doctrine of

limited protection for advertisements is due to a balancing inherent in the policy explanations for the rule,

namely that other types of speech (for example, political) are much more important.

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF FREE SPEECH N INDIA AND IN U.S.

The United States and India almost have similar free speech provisions in their Constitutions. Article

19(1) (a) of Indian constitution corresponds to the First Amendment of the United States Constitution

which says, congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech or of the press4. However,

the provisions in the US Constitution have two notable features i.e. freedom of press is specifically

mentioned therein, No restrictions are mentioned on the freedom of speech.

As far as India is concerned, Supreme Court of India has held that there is no specific provision ensuring

freedom of the press separately. The freedom of the press is regarded as a species of which freedom of

expression is a genus. Therefore, press cannot be subjected to any special restrictions which could not be

imposed on any private citizen, and cannot claim any privilege (unless conferred specifically by law), as

such, as distinct from those of any other citizen.

In the famous case, Express Newspapers (Private) Ltd. v. Union of India, Justice Bhagwati stated, "[that]

the fundamental right to the freedom of speech and expression enshrined in our constitution is based on

(the provisions in) Amendment I of the Constitution of the United States and it would be therefore

legitimate and proper to refer to those decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States of America in

order to appreciate the true nature, scope and extent of this right in spite of the warning administered by

this court against use of American and other cases. As mentioned, the real difference in freedom of

speech enjoyed in the United States and India is a question of degree. India has progressed from an

authoritarian system of control and is now attempting a legislative model of control, quite similar to that

of the United States.

Free speech is meaningless unless it has space to breathe. It is important to note that false statements

made honestly are equally a part of freedom of speech. The supreme court of India applied the famous

doctrine of New York Times v Sullivan standard of American constitutional law against public officials.

The consequence of this very high degree of constitutional protection to freedom of speech in the United

States is that ideas most Americans consider very repugnant, and that may be hurtful to some people, such

as racial hatred, can be expressed freely. At the same time, the expansive protection to freedom of speech

under the First Amendment ensures robust debate on all public issues and the widest dissemination of all

29 Central Hudson Gas & Electric Corp. v. Public Service Commission, 447 U.S. 557 (1980).

COMPARITIVE CONSTITUTION

ideas. As stated above, under the First Amendment, there is no such thing as a "bad idea," and the remedy

for bad speech is said to be "more speech, and not enforced silence. It is part of our culture that people are

"free to speak their mind" and need not fear that they will be sanctioned for saying something that is

offensive or unpopular. The government is not required to and, more importantly, is not permitted to make

decisions about what ideas may be expressed and what ideas may not be expressed. The constitutional

guarantee of freedom of expression under the First Amendment then means freedom of expression in the

fullest sense. For better or worse, this is the American way.

However in the case of India constitutional provisions have been widely influenced by the moral standard

of the society. Constitution has tried to adapt and embody those freedom and restrictions enjoyed by the

Indian people from long time. The provision of freedom of speech and restrictions are the result of that

way of thinking, and this is the Indian way.

In the recent judgment of Shreya Singhal v. Union of India 30, a division bench of the apex court

analysed the position in both countries and identified four major differentiation points.

As a prefatory discussion in the case, the court delved into various American precedents and compared

the First Amendment of the American Constitution to Article 19 of the Indian Constitution and brought

out the similarities and dissimilarities between the two.

The first important difference is the absoluteness of the U.S. first Amendment Congress shall make no

law which abridges the freedom of speech. This has never been given literal effect to. In Chaplinsky v.

New Hampshire , it was held that Allowing the broadest scope to the language and purpose of the

Fourteenth Amendment, it is well understood that the right of free speech is not absolute at all times and

under all circumstances. There are certain well-defined and narrowly limited classes of speech, the

prevention and punishment of which has never been thought to raise any Constitutional problem. These

include the lewd and obscene, the profane, the libelous, and the insulting or 'fighting' wordsthose which

by their very utterance inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace. It has been well

observed that such utterances are no essential part of any exposition of ideas, and are of such slight social

value as a step to truth that any benefit that may be derived from them is clearly outweighed by the social

interest in order and morality.

Second, whereas the U.S. First Amendment speaks of freedom of speech and of the press, without any

reference to expression, Article 19(1)(a) speaks of freedom of speech and expression without any

reference to the press. The American Supreme Court has included expression as part of freedom of

speech and this Court has included the press as being covered under Article 19(1)(a), so that, as a

30 W.P.(Crl).No. 167 of 2012.

COMPARITIVE CONSTITUTION

matter of judicial interpretation, both the US and India protect the freedom of speech and expression as

well as press freedom.

Third, under the US Constitution, speech may be abridged, whereas under our Constitution, reasonable

restrictions may be imposed. Both the U.S. Supreme Court and Indian Supreme Court have held that a

restriction in order to be reasonable must be narrowly tailored or narrowly interpreted so as to abridge or

restrict only what is absolutely necessary.

Fourth, under our Constitution such restrictions have to be in the interest of eight designated subject

matters - that is any law seeking to impose a restriction on the freedom of speech can only pass muster if

it is proximately related to any of the eight subject matters set out in Article 19(2). It is only here that

there is a vast difference. In the U.S., if there is a compelling necessity to achieve an important

governmental or societal goal, a law abridging freedom of speech may pass muster. But in India, such law

cannot pass muster if it is in the interest of the general public. Such law has to be covered by one of the

eight subject matters set out under Article 19(2). If it does not, and is outside the pale of 19(2), Indian

courts will strike down such law.

CONCLUSION

In India, the recent striking down of Section 66A of the Information Technology Act, 2000, is unfortunate

in the context of hate speech, in so much as, even after identifying the problem is in incitement, they

did nothing to restrict the same and struck down the provision in its entirety without even framing any

guidelines.

Considering the communal history of India and the extremely diverse nature of the population with

different cultures and temperaments, it is imperative that the Indian judiciary takes its role seriously and

bears, to its best ability, the part of the responsibility it has to maintain peace and order in the country. For

this, the reasonability of the restrictions to free speech needs to be tested on the touchstone of the

economic and social fabric of India and not merely American judgments and abstract theories of

jurisprudence.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- 2.1 Final Sudarshan GoswamiDocument20 pages2.1 Final Sudarshan GoswamiMoon Mishra100% (1)

- Constitutionality of Media TrialsDocument23 pagesConstitutionality of Media TrialsBhashkar MehtaPas encore d'évaluation

- Defamation - Media LawDocument12 pagesDefamation - Media LawManoj kumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Impact of Globalisation on Indian Stock MarketDocument27 pagesImpact of Globalisation on Indian Stock MarketNadeem Lone0% (3)

- Fundamental RightsDocument23 pagesFundamental RightsPriyanka DograPas encore d'évaluation

- Cyber LawsDocument9 pagesCyber LawsVinoth Persona DulcePas encore d'évaluation

- Defamation Law in India: Balancing Freedom of Speech and Protection of ReputationDocument18 pagesDefamation Law in India: Balancing Freedom of Speech and Protection of Reputation18223 AMOGH MITTALPas encore d'évaluation

- Global Justice SystemDocument25 pagesGlobal Justice SystemstudPas encore d'évaluation

- MRTP Act "Rise, Fall and Need For Change Eco-Legal Analysis"Document18 pagesMRTP Act "Rise, Fall and Need For Change Eco-Legal Analysis"Sourabh SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Media CensorshipDocument13 pagesMedia CensorshipAmit GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Media and Contempt of Court - HiyaDocument14 pagesMedia and Contempt of Court - HiyaHiya BhattacharyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Is The International Court of Justice Biased?Document43 pagesIs The International Court of Justice Biased?CayoBuayPas encore d'évaluation

- Constitutional MoralityDocument2 pagesConstitutional MoralityakitheheroPas encore d'évaluation

- Topic: Apartheid in Israel-Case Study: Rajiv Gandhi National University of Law, PunjabDocument18 pagesTopic: Apartheid in Israel-Case Study: Rajiv Gandhi National University of Law, PunjabhemakshiPas encore d'évaluation

- An Assignment On: Role of Political Parties in DemocracyDocument12 pagesAn Assignment On: Role of Political Parties in DemocracyDENISPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature Review Law and MoralityDocument4 pagesLiterature Review Law and MoralityAmit Singh100% (1)

- Child Labour FootnotessDocument23 pagesChild Labour FootnotessPriyadarshan NairPas encore d'évaluation

- Anti-Dumping Under WTO RegimeDocument17 pagesAnti-Dumping Under WTO RegimeArslan IqbalPas encore d'évaluation

- Constitutional Law FinalDocument13 pagesConstitutional Law FinalMargaret RosePas encore d'évaluation

- Causes, Consequences and Cure of Corruption in IndiaDocument5 pagesCauses, Consequences and Cure of Corruption in IndiaShreyas Singh100% (1)

- The General Principles of Criminal Liability PPNTDocument24 pagesThe General Principles of Criminal Liability PPNTRups YerzPas encore d'évaluation

- Electoral Reforms in India: Addressing Key IssuesDocument43 pagesElectoral Reforms in India: Addressing Key IssuesGangadhar ReddyPas encore d'évaluation

- Data Protection in IndiaDocument4 pagesData Protection in IndiaHrishikesh GoswamiPas encore d'évaluation

- Globalization IhrDocument34 pagesGlobalization IhrkavmancPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Proposal by Ranjith Kodituwakku - Bucks Registration Number - 21808162Document6 pagesResearch Proposal by Ranjith Kodituwakku - Bucks Registration Number - 21808162DhanushkaPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparative Study of Preambles to Indian, US and Canadian ConstitutionsDocument30 pagesComparative Study of Preambles to Indian, US and Canadian ConstitutionsKavit GargPas encore d'évaluation

- Commutative JusticeDocument1 pageCommutative JusticeCrischelle PascuaPas encore d'évaluation

- Cosmopolitanism PDFDocument29 pagesCosmopolitanism PDFviral bhanushaliPas encore d'évaluation

- Human Rights ProjectDocument13 pagesHuman Rights ProjectanonymousPas encore d'évaluation

- Aman ChoudharyDocument40 pagesAman ChoudharyAmanKumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Bureaucracy-A Hindrance To Growth in IndiaDocument25 pagesBureaucracy-A Hindrance To Growth in Indiachandan8181Pas encore d'évaluation

- 12.right To Information Act 2005Document4 pages12.right To Information Act 2005mercatuzPas encore d'évaluation

- Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Reproductive Health MattersDocument10 pagesTaylor & Francis, Ltd. Reproductive Health MattersElijiahPas encore d'évaluation

- Volume 3 Issue 1: Mr. Zubair Ahmed Guest Faculty and Research Scholar, Department of Law, Assam University, SilcharDocument10 pagesVolume 3 Issue 1: Mr. Zubair Ahmed Guest Faculty and Research Scholar, Department of Law, Assam University, Silcharsaiby khanPas encore d'évaluation

- Kashmir Kaur v. State of Punjab. 2013 Cr.L.J.Document11 pagesKashmir Kaur v. State of Punjab. 2013 Cr.L.J.Selina ChalanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Constitutional Amendments ExplainedDocument13 pagesConstitutional Amendments ExplainedGuru RajPas encore d'évaluation

- Vulnerable Groups in India: Chandrima Chatterjee Gunjan SheoranDocument39 pagesVulnerable Groups in India: Chandrima Chatterjee Gunjan SheoranThanga pandiyanPas encore d'évaluation

- BASCO VS. RAPATALO: JUDGE MUST CONDUCT HEARING ON BAILDocument72 pagesBASCO VS. RAPATALO: JUDGE MUST CONDUCT HEARING ON BAILPeasant MariePas encore d'évaluation

- Victimless CrimesDocument8 pagesVictimless CrimesJuan MorsePas encore d'évaluation

- Shubham Bhatia Business Laws-IIDocument19 pagesShubham Bhatia Business Laws-IIshubhambhatia0064Pas encore d'évaluation

- Human Rights in India A Brief StudyDocument4 pagesHuman Rights in India A Brief StudyEditor IJTSRDPas encore d'évaluation

- Tushita SinghDocument69 pagesTushita SinghMaster PrintersPas encore d'évaluation

- Criminal & Security LawDocument6 pagesCriminal & Security LawPrashant SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Emergency in IndiaDocument30 pagesEmergency in IndiaRiya SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- IT Amendment Act, 2008 - An Act To Amend The IT Act 2000Document3 pagesIT Amendment Act, 2008 - An Act To Amend The IT Act 2000sbhatlaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ghanaian media landscape and unethical journalismDocument78 pagesGhanaian media landscape and unethical journalismAzoska Saint SimeonePas encore d'évaluation

- Health Law - AbstractDocument5 pagesHealth Law - AbstractSachi Sakshi UpadhyayaPas encore d'évaluation

- Contempt of Court by Media - A Study - IPleadersDocument10 pagesContempt of Court by Media - A Study - IPleadersPrachi TripathiPas encore d'évaluation

- Right Against Double Jeopardy in IndiaDocument13 pagesRight Against Double Jeopardy in Indiaakshitjain04100% (4)

- Prepare Report On Human Rights Violation in India and Main Reasons Behind Its ViolationsDocument11 pagesPrepare Report On Human Rights Violation in India and Main Reasons Behind Its ViolationsAvaniJainPas encore d'évaluation

- Ethics of the Legal ProfessionDocument20 pagesEthics of the Legal Professiongareth007alcippePas encore d'évaluation

- Excel Wear Etc Vs Union of India & Ors On 29 September, 1978Document24 pagesExcel Wear Etc Vs Union of India & Ors On 29 September, 1978Vishal Gehrana KulshreshthaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chanakya National Law University: Project of Law of History On "Property Rights of Women in Modern India "Document20 pagesChanakya National Law University: Project of Law of History On "Property Rights of Women in Modern India "Vibhuti SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Dr. RAM MANOHAR LOHIYA NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY LUCKNOW Forest Conservation LawsDocument14 pagesDr. RAM MANOHAR LOHIYA NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY LUCKNOW Forest Conservation Lawslokesh4nigamPas encore d'évaluation

- Ch:1 Nature and Classification of Law: Syllabus ContentDocument42 pagesCh:1 Nature and Classification of Law: Syllabus Contentzahra malik100% (1)

- The Path Forward For Digital Assets Adoption In IndiaDocument36 pagesThe Path Forward For Digital Assets Adoption In IndiaAman ShahPas encore d'évaluation

- Cyber PornographyDocument15 pagesCyber PornographySrijan Acharya100% (1)

- The Silver Box: “Love has no age, no limit; and no death.”D'EverandThe Silver Box: “Love has no age, no limit; and no death.”Pas encore d'évaluation

- The International Telecommunications Regime: Domestic Preferences And Regime ChangeD'EverandThe International Telecommunications Regime: Domestic Preferences And Regime ChangePas encore d'évaluation

- Constitutional Regulation of Freedom of ExpressionDocument20 pagesConstitutional Regulation of Freedom of ExpressionJatin BakshiPas encore d'évaluation

- Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University, Lucknow - 226012Document18 pagesDr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University, Lucknow - 226012Aarif Mohammad BilgramiPas encore d'évaluation

- Dismissal of Suit For Default-CpcDocument11 pagesDismissal of Suit For Default-CpcAarif Mohammad BilgramiPas encore d'évaluation

- Nestle Swot AnlaysisDocument3 pagesNestle Swot AnlaysisAarif Mohammad BilgramiPas encore d'évaluation

- 4Th Nuals Maritime Law Moot Court Competition, 2017: in The Permanent Court of ArbitrationDocument27 pages4Th Nuals Maritime Law Moot Court Competition, 2017: in The Permanent Court of ArbitrationAarif Mohammad BilgramiPas encore d'évaluation

- Changing Def of Federalism ConstiDocument23 pagesChanging Def of Federalism ConstiAarif Mohammad BilgramiPas encore d'évaluation

- Domicile-Conflict of LawDocument19 pagesDomicile-Conflict of LawAarif Mohammad BilgramiPas encore d'évaluation

- Section 100 CPCDocument12 pagesSection 100 CPCAarif Mohammad BilgramiPas encore d'évaluation

- Advantages and Disadvantages of NegotitationDocument22 pagesAdvantages and Disadvantages of NegotitationAarif Mohammad Bilgrami75% (8)

- Verbal Ability (CAT)Document9 pagesVerbal Ability (CAT)Anonymous Vx9KTkM8nPas encore d'évaluation

- Ambani Borthers Case-ContractsDocument39 pagesAmbani Borthers Case-ContractsAarif Mohammad Bilgrami100% (2)

- CAT 2018 Syllabus PDFDocument10 pagesCAT 2018 Syllabus PDFAarif Mohammad BilgramiPas encore d'évaluation

- Bankers Lien-Banking LawDocument14 pagesBankers Lien-Banking LawAarif Mohammad BilgramiPas encore d'évaluation

- ILI RULES OF FOOTNOTINGDocument5 pagesILI RULES OF FOOTNOTINGsaurabh887Pas encore d'évaluation

- Rights and Duties of Partners - ContractsDocument17 pagesRights and Duties of Partners - ContractsAarif Mohammad BilgramiPas encore d'évaluation

- Restraint of Trade-ContractsDocument22 pagesRestraint of Trade-ContractsAarif Mohammad BilgramiPas encore d'évaluation

- Application Form Bootcamp+Document13 pagesApplication Form Bootcamp+Aarif Mohammad BilgramiPas encore d'évaluation

- Contracts Project IIIDocument32 pagesContracts Project IIIAarif Mohammad BilgramiPas encore d'évaluation

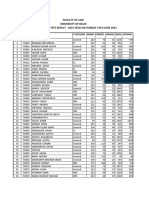

- LL.M. Entrance Test Results 2015 for Delhi University Faculty of LawDocument49 pagesLL.M. Entrance Test Results 2015 for Delhi University Faculty of LawAarif Mohammad BilgramiPas encore d'évaluation

- Delivery of Possession-ContractsDocument11 pagesDelivery of Possession-ContractsAarif Mohammad BilgramiPas encore d'évaluation

- Consti FinalDocument10 pagesConsti FinalAarif Mohammad BilgramiPas encore d'évaluation

- Criminal Law ProjectDocument9 pagesCriminal Law ProjectAarif Mohammad BilgramiPas encore d'évaluation

- Narco Analysis: A Review of its Constitutionality and Evidentiary ValueDocument26 pagesNarco Analysis: A Review of its Constitutionality and Evidentiary ValueAarif Mohammad Bilgrami100% (4)

- BibliographyDocument2 pagesBibliographyAarif Mohammad BilgramiPas encore d'évaluation

- Morality vs Legality of Live-in RelationshipsDocument20 pagesMorality vs Legality of Live-in RelationshipsAarif Mohammad BilgramiPas encore d'évaluation

- Communication To Offer-ContractsDocument20 pagesCommunication To Offer-ContractsAarif Mohammad BilgramiPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Paper Pra Chi Shivam 66 ADocument18 pagesFinal Paper Pra Chi Shivam 66 AAarif Mohammad BilgramiPas encore d'évaluation

- CPL Final ProjectDocument14 pagesCPL Final ProjectAarif Mohammad BilgramiPas encore d'évaluation

- Cyber Law ProjectDocument20 pagesCyber Law ProjectAarif Mohammad Bilgrami100% (1)

- Delay in Criminal AdjudicationDocument32 pagesDelay in Criminal AdjudicationAarif Mohammad Bilgrami0% (1)

- BibliographyDocument2 pagesBibliographyAarif Mohammad BilgramiPas encore d'évaluation

- Fair and FestivalDocument27 pagesFair and Festivalrak0249161Pas encore d'évaluation

- Counter Affidavit For Robbery With Homicide MoscowDocument4 pagesCounter Affidavit For Robbery With Homicide MoscowEmmagine E EyanaPas encore d'évaluation

- SGDU6093 Uality Anagement in Ducation: Dr. Khaliza SaidinDocument11 pagesSGDU6093 Uality Anagement in Ducation: Dr. Khaliza SaidinNazzir Hussain Hj MydeenPas encore d'évaluation

- Mananquil Vs Moico-ReadDocument4 pagesMananquil Vs Moico-ReadPatrick James TanPas encore d'évaluation

- Los Angeles HCIDLA RECOMMENDATION ON THE ADOPTION OF AN ANTI-TENANT HARASSMENT ORDINANCE IN RESPONSE TO COUNCIL MOTION 14-0268-S13Document16 pagesLos Angeles HCIDLA RECOMMENDATION ON THE ADOPTION OF AN ANTI-TENANT HARASSMENT ORDINANCE IN RESPONSE TO COUNCIL MOTION 14-0268-S13law365Pas encore d'évaluation

- Updated AmendmentsDocument79 pagesUpdated AmendmentsWestSeattleBlogPas encore d'évaluation

- Kartu Soal PG Bahasa Inggris 2021Document10 pagesKartu Soal PG Bahasa Inggris 2021SuhayatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Whatever It TakesDocument7 pagesWhatever It TakesScribder45Pas encore d'évaluation

- MV 262Document1 pageMV 262api-327526761Pas encore d'évaluation

- BabaiDocument26 pagesBabaisrisanbalPas encore d'évaluation

- SLS Dav Mun 2023 BG - UnhrcDocument22 pagesSLS Dav Mun 2023 BG - Unhrcharsh242123Pas encore d'évaluation

- Adfelps ListeningDocument13 pagesAdfelps Listeningsunar wan50% (2)

- Derek Chollet - The German Marshall Fund of The United States PDFDocument5 pagesDerek Chollet - The German Marshall Fund of The United States PDFBigBadLeakerPas encore d'évaluation

- 78 People vs. Fernandez, Et Al., 183 SCRA 511, March 22, 1990Document2 pages78 People vs. Fernandez, Et Al., 183 SCRA 511, March 22, 1990Rex100% (1)

- Name: Gelyn B. Olayvar Section: LOC-N1 Schedule: Saturday 1:00-4:00 P.MDocument4 pagesName: Gelyn B. Olayvar Section: LOC-N1 Schedule: Saturday 1:00-4:00 P.MGelyn OlayvarPas encore d'évaluation

- Deadlands Noir Companion CompressDocument209 pagesDeadlands Noir Companion CompressWade100% (1)

- Robert Reeves ComplaintDocument56 pagesRobert Reeves ComplaintAlexandria DorseyPas encore d'évaluation

- Along the Iron Curtain from Sea to SeaDocument43 pagesAlong the Iron Curtain from Sea to Searisbo12100% (1)

- Compiled Case Digests.Document48 pagesCompiled Case Digests.Irish Ann Fabros100% (1)

- Concept Paper DraftDocument6 pagesConcept Paper DraftIrish Shane Vergara LudiaPas encore d'évaluation

- USAA Cashback Rewards Checking Rewards Program Terms and ConditionsDocument2 pagesUSAA Cashback Rewards Checking Rewards Program Terms and ConditionsAprice95Pas encore d'évaluation

- ScriptDocument5 pagesScriptHaroon HamidPas encore d'évaluation

- Alunos EswII - PREDocument2 pagesAlunos EswII - PREPedro HenriquePas encore d'évaluation

- Contract Skilled WorkerDocument2 pagesContract Skilled WorkerMaryam Hatim AfanehPas encore d'évaluation

- Shari'Ah Law 1 Case DigestsDocument28 pagesShari'Ah Law 1 Case DigestsLilyyPas encore d'évaluation

- VBM Freccia Land Tactical Command PostDocument1 pageVBM Freccia Land Tactical Command PostThallezPas encore d'évaluation

- Crow Lake DDDocument2 pagesCrow Lake DDJustForPrint0% (1)

- By Brad Smith: A Rapid Fire 2 Scenario V1.0.2 (9/1/08)Document5 pagesBy Brad Smith: A Rapid Fire 2 Scenario V1.0.2 (9/1/08)JMMPdosPas encore d'évaluation

- CIR Vs Mirant PagbilaoDocument2 pagesCIR Vs Mirant PagbilaoTonifranz Sareno50% (2)

- Sex God SecretsDocument123 pagesSex God SecretsKhamiss Khouya55% (20)