Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Leahey & Moody (2014) - Sociological Innovation Through Subfield Integration

Transféré par

RB.ARGTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Leahey & Moody (2014) - Sociological Innovation Through Subfield Integration

Transféré par

RB.ARGDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

540131

research-article2014

SCUXXX10.1177/2329496514540131Social CurrentsLeahey and Moody

Sociological Innovation

through Subfield Integration

Social Currents

2014, Vol. 1(3) 228256

The Southern Sociological Society 2014

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/2329496514540131

scu.sagepub.com

Erin Leahey1 and James Moody2,3

Abstract

Is domain-spanning beneficial? Can it promote innovation? Classic research on recombinant

innovation suggests that domain-spanning fosters the accumulation of diverse information and

can thus be a springboard for fresh ideasmost of which emanate from the merger of extant

ideas from distinct realms. But domain-spanning is also challenging to produce and to evaluate.

Here, the domains of interest are subfields. We focus on subfield spanning in sociology, a

topically diverse field whose distinct subfields are still reasonably permeable. To do so, we

introduce two measures of subfield integration, one of which uniquely accounts for the novelty of

subfield combinations. We find (within the limits of observable data) the costs to be minimal but

the rewards substantial: Once published, sociology articles that integrate subfields (especially

rarely spanned subfields) garner more citations. We discuss how these results illuminate trends

in the discipline of sociology and inform theories of recombinant innovation.

Keywords

science knowledge, boundary spanning, higher education, networks, multilevel models,

innovation

How is new and useful knowledge produced?

Classic and recent literature suggests that

spanning boundaries and pooling diverse

information from distinct knowledge domains

is essential. Adam Smith ([1766] 1982:539)

argued that when the mind is employed about

a variety of objects it is somehow expanded

and enlarged. Katz and Lazarsfeld (1955:345)

noted that people who see and act on differences across groups, and bridge them, have an

advantage in detecting and developing rewarding opportunities. More recent scholarship

suggests that information pooled from disparate sources provides a (if not the) foundation

from which new combinations and ideas spring

(Abbott 2001; Fleming, Mingo, and Chen

2007; Hargadon 2002). The close link between

domain spanning and idea generation is captured in the term recombinant innovation

(Weitzman 1998).

Yet scholars are beginning to question the

benefits of domain-spanning in academe and

to document associated challenges. Jacobs and

Frickel (2009) show that the benefits of domain

spanning are largely unsubstantiated, so enthusiasm may be premature. In fact, domain-spanning ideas face numerous challenges. On the

producer side, it is difficult to search unfamiliar topics (Fleming 2001; Schilling and Green

2011), to master and adequately represent literature

from

distinct

subfields,

to

accommodate the research mores of multiple

1

University of Arizona, Tucson, USA

Duke University, Durham, NC, USA

3

King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

2

Corresponding Author:

Erin Leahey, Department of Sociology, University of

Arizona, P.O. Box 210027, Tucson, AZ 85721-0027,

USA.

Email: leahey@arizona.edu

Downloaded from scu.sagepub.com by guest on June 23, 2015

229

Leahey and Moody

specialty areas (Lamont, Mallard, and

Guetzkow 2006), and to produce output that is

standard in form and content. On the audience

side, reviewers drawn from the representative

domains may evaluate the merits of a work

very differently (Lamont 2009; Lamont et al.

2006; Mansilla 2006), leading to low interreviewer reliability that, in turn, increases the

likelihood of rejection.

The goal of this article is to critically apply

these ideas to academic scholarship. How do

domain-spanning academic articles fare? Do

they benefit from the diverse perspective,

tools, and theories that different domains offer,

as the recombinant innovation literature suggests? Or does their integrative character make

them challenging to produce and evaluate?

These questions are important to answer

because domain spanning is ubiquitous in academe; for example, interdisciplinary scholarship is on the rise (Brint 2005; Jacobs and

Frickel 2009), perhaps because most research

problems lie at the intersection of established

ideas (Braun and Schubert 2003). To address

these questions, we focus on the field of sociology, a diverse discipline integrating many

topics (Clemens et al. 1995) with robust yet

permeable subfields1 (Moody 2004). Our study

of inter-subdisciplinary scholarship elucidates

the process of (knowledge) product legitimation and increases our understanding of how

scientific knowledge evolves (Mulkay

1974:228). More immediately, our research

speaks to ongoing academic debates about the

state of social science disciplines, especially

concerns about increasing specialization and

fragmentation in sociology.

This article makes contributions in terms of

theory, measurement, and the substantive

topic.Theoretically, we introduce the concept

of subfield integration and demonstrate its relevance to scholarship on recombinant innovation and on the evaluation of domain-spanning

work. We then develop two measures of such

scholarly domain spanning: a binary one that

measures whether domain-crossing occurs

(which we call nominal integration) and a

more refined one that incorporates the distinctiveness of the pairing (which we call novel

integration). Use of alternate measures allows

us to assess two mechanisms that may explicate the aforementioned benefits of integration: Is it merely access to a broader audience

(i.e., members of two subfields rather than

one) that enhances value, or is the novelty of

the research implicated? While we cannot

measure innovation directly, we assess whether

novelty is one reason why subfield integration

accrues benefits. Thus, like Fleming et al.

(2007), we distinguish between novelty (a

mechanism we tap by juxtaposing two measures of subfield integration) and usefulness

(the outcome of interest). Our results show that

there are consistent, strong, and meaningful

positive returns to subfield integration.

The Concept of Integration

Integration across disciplinesinter-disciplinarityhas received much scholarly attention

(Abbott 2001:131; National Academies of

Science 2005; Rhoten and Parker 2006), but

integration within disciplineswhat we call

subfield integrationis much less studied.

While this likely reflects the topical homogeneity of many disciplines (Moody and Light

2006), it is an obvious lacuna in broad, diverse

fields like sociology where the internal driver

of new ideas might well come from integrating

subfields. This imbalance, which we begin to

rectify in this article, is surprising given that

processes that occur both between and within

disciplines are critical to adequately capturing

the the substantive heart of the academic system (Abbott 2001:148). Like fields, subfields

produce insights, provide structure to the academic labor market (where advertisements for

positions are distinguished by both field and

subfields), and prevent knowledge from

becoming too abstract and overwhelming for

scholars (Abbott 2001).

An influential working definition of interdisciplinary research is adaptable to the kind of

integrative research that interests us: that

which spans or bridges subdisciplines. The

National Academies report (National

Academies of Science 2005:188) defines interdisciplinary research as a mode of research . . .

that integrates perspectives, information, data,

techniques, tools, perspectives, concepts, and/

Downloaded from scu.sagepub.com by guest on June 23, 2015

230

Social Currents 1(3)

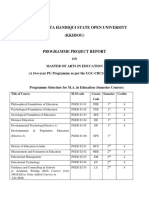

Figure 1. Growth in number of American Sociological Association sections.

or theories from two or more disciplines or

bodies of specialized knowledge. By analogy,

we define subfield integration as the borrowing or mixing of insights from two or more

subfields within a discipline. While perhaps

less stable than disciplines, subfields are the

building blocks of science (Small and Griffith

1974). Whereas disciplines form the teaching

domain of science, smaller intellectual units,

nestled within and between disciplines constitute the research domain of science (Chubin

1976) and thus are most relevant to a study of

scholarly innovation. Subfields are the microenvironments for research (Hagstrom

1970:93) that provide potential interconnections (Ennis 1992:260). According to our

definition, an article on student performance

might fall cleanly within the subfield sociology of education, but an article that examines

gender differences in student performance

might be drawing fromand speaking back

tothe research literature in two subfields,

sociology of education as well as gender,

and thus be considered integrative.

Internal divisions like subfields may be particularly important in low consensus fields

(Shwed and Bearman 2010) like sociology.

Subfields are largely distinguished by their

substantive focus of inquiry (more so than

methodological or theoretical approaches,

where there is overlap) and typically have their

own American Sociological Association

(ASA) section, journal(s), and conferences. As

these subfields grow in number (see Figure 1),

so do the opportunities for combination and

cross-fertilizationwhat we call subfield integration. Numerous studies in the 1990s used

data on ASA section comemberships or cocitation patterns to identify sociologys subdisciplinary structure (Cappell and Gutterbock

1992; Crane 1972; Ennis 1992). These studies

show that while subfields are clearly distinct,

some hang together more than others, forming

a loosely coupled system. This is also apparent

in our data (for the period 19852004) as

depicted in Figure 2. Proximate fields possess

cognitive overlaps that are based largely on

ideas and subject matter (Cappell and

Gutterbock 1992; Edge and Mulkay 1975). It

is near the edges of subfields, where they overlap with other subfields, that innovations are

most likely to emerge (Chubin 1976).

While most scholars simply assess whether

domain spanning has occurred (Clemens et al.

1995; Jacobs and Frickel 2009), consideration of

the novelty of the pairing is important for clarifying innovation processes. Only a few attempts

have been made to assess the uniqueness, or rarity, of combinations (Braun and Schubert 2003;

Carnabuci and Bruggeman 2009; Rosenkopf

and Almeida 2003; Schilling and Green 2011;

Uzzi et al. 2013). This is ideal because it is new

connections that characterize originality

(Guetzkow, Lamont, and Mallard 2004). The

Downloaded from scu.sagepub.com by guest on June 23, 2015

231

Leahey and Moody

Figure 2. Observed subfield integration, 19852004.

Note. Edges present if subfields share more than 1.75 (Expected value).

most fertile creative products are drawn from

domains that are far apart (Poincare [1908]

1952) and the best conceptual metaphors are

those that create ties across great distances

(Knorr Cetina 1980). Put simply, integrative

work can be more or less innovative, depending

on the relationship between the integrated entities (Carnabuci and Bruggerman 2009:608).

Thus, for our analysis of subfields, it is possible

to examine not only whether two subfields are

spanned (which we call nominal integration)

but also how rarely they are spanned, which

gives us an indication of the novelty of the pairing (which we call novel integration).2

The scholarship on domain-spanning also

tends to neglect time (see Carnabuci and

Bruggeman 2009 for an exception). When considering the effects of subfield integration, it

may be critical to assess the trajectory of each

combination. In sociology, the combination of

poverty and culture was on the wane 1985

2004, but the combination of poverty and

urban sociology was on the rise. A rare-andgetting-rarer combination may reflect something of a dead endreflecting a combination

that used to be of interest but is no longer,

while a rare-but-increasingly common combination reflects a growth area that might signal

disciplinary excitement. Bridges do decay

(Burt 2002; Ryall and Olav 2007), and the

advantages of bridging distinct domains,

which we discuss below, decline when

Downloaded from scu.sagepub.com by guest on June 23, 2015

232

Social Currents 1(3)

everyone strives for them (Buskens and van de

Rijt 2008).

The Effect of Integration

Scholarship on the effect of domain-spanning

is divided. This is likely because innovation is

a risky endeavor that is challenging but potentially beneficial. We tailor these ideas to the

context of academe (where domain-spanning

is positively valued) and the case of sociology

(where robust subfields are clearly distincta

majority of articles fall in a single subfield

but spanning is common enough to allow

exploration) (Clemens et al. 1995; Moody

2004). As elaborated below, we expect that

although challenges may be confronted in the

short term, benefits of subfield spanning likely

emerge in the long term.

Challenges

Scholarship on academia has documented a

number of challenges associated with domainspanning research (Cummings and Kiesler

2005). On the producer side, it is difficult for

scholars to accommodate the research mores

and concepts of multiple specialty areas

(Lamont et al. 2006), to master and adequately

represent literature from distinct subfields, and

to produce output that is standard in form and

content (Bauer 1990). On the audience side,

experts in different subfields may disagree on

the merits of an article (Lamont 2009), and this

conflict may be particularly evident during the

peer-review process (Mansilla 2006).

Birnbaum (1981) found that research that does

not fit neatly within the substantive bounds of

normal science is typically received by journal editors and reviewers with irritation, confusion, and misunderstanding. This makes the

road to journal publication challenging (Ritzer

1998). Former sociology journal editors reinforced this point. Sociological Forum editor

(19931995) Stephen Cole (1993:337)

believed that if an author writes an article on a

relatively narrow subject . . . the chances of the

article being accepted are significantly greater

than if the author is more ambitious. American

Sociological Review (ASR) editor (19781980)

Rita Simon (1994:34) noted that works of

imagination, innovation, and iconoclasm may

fail to receive positive appraisals from reviewers who are good at catching errors and omissions but might miss a gem, or at least the

unusual, the provocative, the outside the mainstream submission.

These challenges are likely tempered, or

partly off-set, in academic sociology, the discipline we study here. First, academe (especially

of late) operates under the general presumption

that domain spanning is beneficial to science

and perhaps scientists as well (Jacobs and

Frickel 2009). This is evident from the recent

enthusiasm for interdisciplinarity (National

Academies of Science 2005), synthesis (Parker

and Hackett 2012), as well as cross-cutting

funding initiatives like National Science

Foundations (NSF) Creative Research Awards

for Transformative Interdisciplinary Ventures

(CREATIV).3 Second, the rise of collaboration

in academic science, including sociology

(Hunter and Leahey 2008; Moody 2004), combined with a division of labor based largely on

subfield expertise (Leahey and Reikowsky

2008), suggests that integrative sociology articles may be becoming easier to produce. Third,

unlike behavioral sciences like psychology

(which has a limited number of distinct and

highly autonomous subfields), sociology has a

plethora of subfields but comparatively weak

boundaries dividing them (Moody 2004).

To the extent that challenges remain under

these more welcoming circumstances, integrative research entails risk. Given the difficulties that integrative work experiences in

the review process, it likely gets rejected

repeatedly and ends up in a low-tier journal.

Authors, ever aware of the advantages of toptier publication for promotion and scholarly

impact, typically submit an article to the most

prestigious journal they think it can be published in and turn to less prestigious journals

if it is rejected (Calcagno et al. 2012). But

there is also a (perhaps small) chance that

integrative work will strike big and get

accepted in a top journal. In sociology, the

three top journals are generalist in nature:

They publish articles on any sociological

topic and strive to publish articles of interest

Downloaded from scu.sagepub.com by guest on June 23, 2015

233

Leahey and Moody

to many sociologists. One top journal explicitly aims to publish integrative work: ASR

asks reviewers to assess whether a submitted

manuscript speaks to two or more subfields,

and if not, how it could be revised to do so

effectively.4 The top journals also aim to publish

the very best, most innovative research. Thus,

we expect integration to have a curvilinear,

U-shaped effect on journal prestige. Integration

will generally have a negative effect on journal prestige, except for the most innovative

integrative articles that may be more likely to

appear in top journals.5

Of course, the biggest penalty an article

can incur is relegation to the notorious file

drawer: It never gets accepted for publication.

Like almost all research on science, we rely

on archival data that is subject to selection

bias (Fleming et al. 2007:464): Unpublished

articles are not observed and may be more

integrative than published articles. We thus

cannot know whether some subset of integrative articles is so difficult to frame successfully, and so challenging to review, that its

authors give up trying to publish it (or never

try at all). We alleviate this concern somewhat by our sampling technique, described

below, which captures elite as well as low-tier

journals; much research only investigates the

former (Clemens et al. 1995; Karides et al.

2001). We also perform sensitivity analyses

to mimic the effect that selection bias might

have on our results so we can gauge the magnitude and direction of bias.

Benefits

Research on creativity and innovation demonstrates that drawing on ideas from diverse

domains is advantageous. Actors and organizations that span domains are exposed to diverse,

unrelated ideas that can be recombined in new

ways (Carnabuci and Bruggerman 2009). Such

new combinations produce good ideas (Burt

2004), higher quality output (Singh 2008), and

serve as a foundation for innovation (Hargadon

2002; Schumpeter 1939; Weick 1979;

Weitzman 1998). As Uzzi and Spiro (2005:447)

summarize, We know that creativity is spurred

when diverse ideas are united or when creative

material in one domain inspires or forces fresh

thinking in another.

When applied to academic science, the

domains of interest are typically disciplines. A

recent study conducted by the National

Academies of Science (2005) argues that

breakthroughs in research will increasingly

occur at the interstices of disciplines, where

substantive areas of inquiry are blended.

According to Burt (2004), scientists are stimulated most by people outside their own discipline; the shock of the interface is what is

interesting and sparks creativity. Bringing

together two new things and seeing their correspondencewhat Knorr Cetina (1980)

refers to as making conceptual metaphors

promotes the extension of ideas and knowledge (Weisberg 2006). Fleming et al. (2007)

find that working with diverse scientists and

having diverse work experiences facilitates the

generation of new ideas.

The benefits of domain spanning should

also extend to subfields. Within academe, there

exists a tight correspondence between fields

and subfields. Processes that occur both

between and within disciplines are critical to

adequately capturing the the substantive heart

of the academic system (Abbott 2001:148),

though subfields better reflect the realm of

research (Chubin 1976). Like fields, subfields

produce the same insights (albeit through different routes), emerge via similar processes,

provide a structure to the academic labor market (where advertisements for positions are

distinguished by both field and subfields), and

help academics by preventing knowledge from

becoming too abstract and overwhelming

(Abbott 2001). Because subfields of a single

discipline are not as diverse as a set of disciplines, the benefits of subfield spanning may

not be as great as the benefits of field spanning. However, the sheer number and variety

of subfields, especially in a discipline as

diverse and loosely coupled as sociology, suggest that many opportunities for recombinant

innovation exist. By linking areas of research,

we gain tentative bridges between local

knowledges and a highly creative product

(Abbott 2001). Thus, scholarship that pools

ideas from diverse subfields should generate

Downloaded from scu.sagepub.com by guest on June 23, 2015

234

Social Currents 1(3)

new and valued ideas. Arguably, the greatest

benefit in reputational work organizations

(Whitley 2000) like academe is having ones

research recognized and highly regarded by

others. While this may be difficult for integrative, unconventional articles to achieve in the

review stage, it may be more likely once they

have been legitimated by publication in a peerreviewed journal. Thus, in the academic context we study here, we expect integrative

research to be more highly valued than non(or less novel) integrative research, at least

after publication. Even if challenges emerge in

the review stage, integrative research may

begin to accrue benefits after it is published.

One intuitive mechanism driving such benefits has been uncovered by previous research; in

this article, we propose and test another. Extant

research suggests that one route to scholarly

influence is to widen ones prospective audience by appealing to multiple communities. For

example, Lamont (1987) found that Derridas

ability to speak to several publics, to make his

scholarship adaptable, and to publish in various

outlets contributed to his influence both within

and outside of France. Scholars able to master

multiple genres are more likely to gain entry to

multiple conversations (Clemens et al. 1995);

indeed, the number of different journals a scientist publishes in is the largest predictor of subsequent H-index (Acuna, Allesina, and Kording

2012). Here, we test an additional mechanism:

Compared with non- (or less novel) integrative

research, integrative research appeals to scholars because of its novelty. We are able to access

this black box by first controlling for subfield

productivity (a proxy for audience size) and

then assessing the relative impact of our two

measures of integration: If it is not merely the

spanning of subfields (nominal integration) but

also the rarity of the combination (novel integration) that makes research articles noteworthy, then we can conclude that our proposed

mechanism is operating.

Scrutinizing the nature of the audience

helps reconcile our two hypotheses. Those

who decide whether an article gets published

in a given journal (editors and reviewers) and

those who cite published work (researchers)

are members of the same scholarly community

who fulfill multiple roles. Indeed, the manuscript reviewer in stage 1 (who may find integrative work challenging to review) may also

be the scholar in stage 2 (who finds integrative

work valuable and worth citing). How can we

argue that they may penalize integrative work

at one stage and value it at the next? The

answer relies on different role expectations.

Peer reviewers are solicited for their expertise,

so in this capacity, scholars provide a critical

evaluation of an article, emphasizing revisable

quality over inherent quality (Ellison 2002).

Outside their reviewer role, researchers choose

the scholarship they read, and they read to

engage with it and to glean its relevance to

their own research.

The overarching goals of this article are to

develop and measure the concept of subfield

integration, and to assess whether the challenges of integrative research are manifested in

the review stage (i.e., by appearing in lowprestige journals) and whether benefits accrue

after publication (i.e., by being cited heavily

by peers). If we find that all but the most novel

integrative articles tend to be published in lowtier journals, then we will feel confident that

the challenges of domain spanning extend to

academic sociology. If we find that not only

nominal integration but also novel integration

(articles that span rarely spanned, cognitively

distant subfields) is valued more highly by the

scientific community, then we will feel confident that we have empirically tapped a process

that is critical to scientific innovation.

Data and Method

Sample

To investigate the potential benefits of integrating subfields, we examine journal articles

written by a 20 percent probability sample of

tenured and tenure-track faculty members

located in sociology departments at Extensive

Research Universities6 in spring 2004. Details

are provided in Appendix A. The sampling

frame was constructed using faculty lists on

department Web sites, which were more upto-date than the ASA Guide to Graduate

Departments. We limit scholars articles to

Downloaded from scu.sagepub.com by guest on June 23, 2015

235

Leahey and Moody

those published on or after the first occurrence

of integrative research in Sociological

Abstracts (SA) in 1985 and to those published

on or before 2004, to give recent articles some

time to accumulate citations. This results in a

sample of 1,785 articles by 180 sociologists,

housed in 99 universities. Our statistical

approach capitalizes on this multistage sampling procedure, but because most scholars

produce both integrative and non- (or less

novel) integrative work,7 the research article

serves as the unit of observation.

This sampling strategy is appropriate for

the task at hand. The vast majority of peerreviewed research takes place at research universities (Levin and Stephan 1989). By

selecting only Extensive Research Universities,

we control for resource-based influences on

the outcomes of interest, such as productivity

expectations, and time and money for research

(Fox 1992). By selecting individuals and their

articles, we gain enough articles per person to

evaluate person- and department-level effects

and to account for unmeasured characteristics

at these levels.

Like many previous studies of inequality in

science (Keith et al. 2002; Long 1992; Reskin

1977), we study a single discipline. We do this

because disciplines differ in terms of their

stratification processes (Fox and Stephan

2001; Levin and Stephan 1989; Prpic 2002),

their degree of receptivity to boundary-crossing research, and the degree to which their

work is cited in other fields (Pierce 1999). We

study sociology because the social sciences

have generally been neglected by the sociology of science and knowledge (Guetzkow et

al. 2004). Moreover, sociology sits at the

crossroads of several different disciplines; it is

embedded in multiple fields, potentially

speaking to many audiences (Clemens et al.

1995; Moody and Light 2006) making an

investigation of integrative research in this discipline particularly informative. The permeability of sociologys subfields (Moody 2004)

provides a conservative test of the effects of

domain spanning: If we find effects in sociology, they are likely more pronounced in fields

like psychology and economics where subfields are more insular.

This study, like most studies of academic

rewards (Allison and Long 1987; Ferber and

Loeb 1973; Fox and Faver 1985; Moody 2004;

Reskin 1978; Ward and Grant 1995; Xie and

Shauman 1998), is based only on journal articles and does not include other forms of scholarly publication, most notably books. This is a

limitation imposed by our reliance on SA to

obtain keywords (discussed below), which we

use to measure integration. However, previous

studies have found that article productivity

correlates strongly with total productivity that

includes books, book reviews, and contributions to edited volumes (Clemens et al. 1995;

Leahey 2007; Reskin 1977, 1978). Articles and

books differ largely in terms of their method

and evidence, not substantive subfields

(Clemens et al. 1995), which serve as the basis

of the integration measure we use here.

Data Sources

Most of the data needed to construct our key

explanatory variable, subfield integration, and

other article-level variables (all described in

the next section) were obtained from the electronic database Sociological Abstracts (SA).

By entering sampled sociologists names, we

accessed all of their refereed journal articles.8

For each article, we collected classification

codes (keyword descriptors indicating disciplinary subfieldssee the entire list in

Appendix B), which are assigned by staff at

Cambridge Scientific Abstracts (CSAs), the

umbrella organization that manages the database.9 SA applies at least one and sometimes

two classification codes to each article. While

other aspects of articles (e.g., abstracts, text,

bibliography) also indicate its content, keywords give a good indication of each articles

substantive topic, map easily onto ASA sections that demarcate substantive areas of study,

and help structure professional identity within

the field. Because there is a fixed set of classification codes assigned by information science

experts at SA, they are easier to work with analytically than an open-ended list generated by

authors or a Web of Science algorithm (e.g.,

there is no need to construct a thesaurus for

similar terms). Classification codes have been

Downloaded from scu.sagepub.com by guest on June 23, 2015

236

Social Currents 1(3)

used extensively in previous work on sociological subfields (Leahey 2006, 2007; Moody

2004) and serve as the basis for our key

explanatory variable (subfield integration) as

well as two control variables: subfield prestige

and subfield productivity. Later, we show that

our results are robust to the use of an alternate

classification scheme.

We rely on the Thomson Reuters Web of

Science to construct two outcome variables. To

assess whether integrative research ends up in

lower-tier journals, we collected data on journal prestige from Journal Citation Reports, a

comprehensive and unique resource tool that

allows you to evaluate and compare journals

using citation data.10 To assess whether integrative research is more highly valued, we collected data on each articles citation counts as

of 2010, from the Web of Science.

Additional data about scholars, their respective departments, and their subfields were

obtained from department Web pages, professional association directories, and curriculum

vitae (CVs), which provide data comparable to

other sources of career histories (Dietz et al.

2000; Heinsler and Rosenfeld 1987). We

obtained the prestige rating of each scholars

department from the National Research

Council (NRC) (Goldberger, Maher, and

Flattau 1995).

Measures

Key explanatory variables.We use two measures of the key explanatory variable: subfield

integration. Both measures are based on extant

keywords from SA; they are not based on the

authors own classifications of their articles.

The less precise measure is binary and captures what we call nominal integration. It

indicates whether the article was assigned keywords that come from more than one keyword

family. A keyword family comprises a parent code and several child codes. In SAs classification system (Appendix B), there are 29

parent codes containing 94 child codes. For

example, the parent code complex organization contains several child codes, including

bureaucratic structure and jobs and work

organization. If an article was assigned one

code belonging to the social control family

and one code from the complex organization

family, then it would be considered integrative. If an article received two codes from the

same family, then it would not be considered

integrative. Just over one-quarter (470/1785)

of the sociologists articles were classified as

integrative according to this binary measure. A

validity check suggests that the measure we

use is quite good at distinguishing integrative

from nonintegrative articles.11

The more refined measure of integration is

continuous and captures what we call novel

integration. The measure captures not only

whether two subfields are combined but also

the rarity (and thus novelty) of the combination. Like similar measures used by others

(Schilling and Green 2011; Uzzi et al. 2013),

we control for chance occurrence based on the

size of each subfield by using the expected

number of integrative articles. For each nonzero cell, we calculate novel integration as 1

[observed/expected], and where the expected

number of cross-subfield publications is calculated in the standard manner: Eij = pi pj T,

where pi is the proportion of articles in subfield

i, and T is the total number of articles published.12 Thus, as the number of observed

cross-subfield articles approaches the number

expected by chance, the value approaches

zero, and the article is thus not very integrative. When we see more cross-subfield publications than expected by chance, the article has

a low score on the novel integration scale.

When we see fewer cross-subfield publications than expected by chance, the article has a

high score on the novel integration scale.13

Uniquely, our calculation of novel integration

is based on a time-sensitive co-classification

matrix, akin to the one presented in Appendix

Cwhich shows frequencies for all combinations during the entire time period under study

(19852004)but restricted to the five-year

window prior to each articles publication date.

Assuming that any cross-subfield publication

is more integrative than a publication that falls

only within one category, we hard-code all

single-category (i.e., nonintegrative) publications to just below the observed minimum

(7).14 Finally, for ease of interpretation, we

Downloaded from scu.sagepub.com by guest on June 23, 2015

237

Leahey and Moody

rescale the score, using percentiles, so that it

ranges from 1 to 100.

To illustrate, consider articles with two contrasting combinations, both published in 1995:

One is associated with the codes for Gender

(29) and Organizations (06), the other is associated with the codes for Political Sociology

(09) and Family (19). (Appendix C provides

the prevalence of each combination among all

integrative articles published between 1985

and 2004not just the articles in our sample.)

When we restrict it to the five years prior to

publication (19901995), we find that 267 articles are classified as both Gender and

Organizations. While these are both large subfields, with 2,119 Gender articles and 1,431

Organizations articles (out of a total of 24,521

articles), we would only expect to find 123.6

integrative articles [(2,119 1,431) / 24,521],

so the novel integration score is 1(267 /

123.6)=1.16 (84th percentile), indicating that

this is a fairly common (and not so novel) combination. On the contrary, we find 33 articles

classified as both Political Sociology and

Family (containing 1,284 and 2,200 articles,

respectively), we would expect to find 115.2

articles by chance [(1,284 2,200) / 24,521],

and so the 33 observed articles in the 1990

1995 window results in a novel integration

score of 1(33 / 115.2) = 0.71 (which would

put it in the 100th percentile).

With data covering a span of almost 20 years,

and an interest in distinguishing short- and longterm effects, it is important to account for time.

We do this in three ways. First, we construct and

use a time-sensitive co-classification matrix

(i.e., a five-year window prior to each articles

publication date) to measure novel integration,

as described above. Second, we control for year

of publication in the analyses. Third, we control

for the trend in each combinations popularity.

Two articles published in the same year could

have the same novel integration score, but their

respective combinations could be on very different trajectories. For example, the combination of poverty and culture was on the wane

19852004 (suggesting perhaps a dead end),

but the combination of poverty and urban sociology was on the rise (indicating disciplinary

excitement). To ensure that slopes are scaled

similarly across categories, we first standardize

the data to have a global mean of 0 and standard

deviation of 1, and then calculate slopes for

each category combination. We use a periodspecific slope, using two periods (before or after

1995), as a way to capture the general trend relevant to each articles publication date.15

Outcome variables.To assess potential challenges of integrative work, we examine journal prestige. This is captured by the Web of

Sciences journal impact factor (JIF), calculated as the number of citations to recent

(within the past few years) articles in the journal divided by the number of articles recently

published, and thus is the average number of

citations per article. We assign a value of

0.005 to journals that are not indexed by the

Web of Science (which indexes 1,000 social

science journals) and thus omitted from the

Journal Citation Reports.16 Impact factors are

available only from 1997 onward; because

they shift somewhat from year to year, we use

the average of the factors from 1997, 2000,

and 2003. The JIFs correlate very highly with

sociologists general perceptions, and also

with Allens (1990) assessment of journal

influence,17 which we cannot use because it is

only available for a small fraction of the journals represented in our sample.

We use a cumulative citation count to test

our second hypothesis: that integrative research

is viewed as more innovative and thus will be

more noteworthy to other scholars. Specifically,

the cumulative number of citations that each

article has received as of fall 2010 captures the

extent to which the work was useful toand

valued byother scholars.18 Although selfcitations are not eliminated from this count,

Clemens et al. (1995:455) found these to be

rare, and there are few differences in motivation for citation to self and to others (Bonzi and

Snyder 1991). Articles that have never been

cited are given a value of 0.005, and the entire

variable is then log transformed.19

Both outcome measures rely on citations,

whichdespite various criticismsare generally accepted as an indicator of an articles

impact. Certainly, citation counts may also be

reflecting the authors visibility, disciplinary

Downloaded from scu.sagepub.com by guest on June 23, 2015

238

Social Currents 1(3)

alliances, attempts to flatter potential reviewers,

or even the controversial nature of an article

(Baldi 1998; Ferber 1986; Latour 1987).

Authors may cite previous work in a casual

way, or rely on it heavily. They may think of it

highly, or dismiss it as flawed. Despite this variation in what a citation signals (van Dalen and

Henkens 2005), citation counts reflect the usefulness of an article because it contributed, in some

way, to a subsequent work. This is largely accepted

by the academic community, which continues to

rely on citation counts when making decisions

about merit raises, promotion, and tenure

(Diamond 1986; Sauer 1988; Leahey et al. 2010).

Control variables. In addition to the trend in each

combinations popularity, other characteristics

of subfields likely influence the impact of articles written in those areas. For example, even a

nonintegrative article may garner a fair number

of citations if the single subfield it addresses is

highly productive. There are also sharp differences in the frequency with which different subfields are cited (Clemens et al. 1995:472). For

these reasons, we control for the productivity

and prestige of the subfield(s) corresponding to

each article. Subfield productivity is captured by

counting the number of articles (in the population of articles appearing in SA 19852004) that

were assigned each possible keyword descriptor, which also helps alleviate concerns about

fluctuations in small-topic areas. For articles

that spanned more than one subfield (i.e., had

multiple keyword descriptors), we summed the

counts from the respective subfields. A rough

proxy for subfield prestige is the number of

times each subfield (keyword descriptor)

appeared in (or was applied to an article appearing in) American Journal of Sociology (AJS),

American Sociological Review (ASR), or Social

Forces (SF) in the year 2003.

We also control for other variables that may

confound the relationships of interest. Because

coauthored articles tend to be cited more

(Wuchty, Jones, and Uzzi 2007), we include a

control variable for sole-authored articles. We

also control for whether the article can be considered theoretical, methodological, or both

(i.e., receiving both the theory and the method

keyword). Because disciplinary lore suggests

that qualitative work might be more difficult to

publish in top-tier journals, and that quantitative work may squeeze out creativity and perhaps integrative impulses (Blalock 1991; Ritzer

1998), we control for whether the article uses

quantitative methods. Instead of relying, as

Moody (2004) did, on the number of tables presented in the article as a proxy for quantitative

methods, we use a more conservative measure,

which only classifies articles as quantitative if

they have a quantitative methods keyword

assigned to it by SA. We control for year of

publication because more recently published

articles are disadvantaged in terms of exposure

(i.e., opportunity to be cited), and also because

almost all research is cited less frequently over

time (Dogan and Pahre 1990). Last, when the

outcome of interest is an articles citation count,

we also control for JIF.

We also account for several author-level

attributes and one department-level characteristic. Because newcomers to a field are more

likely to instigate paradigm shift (Collins

1968:136) and more established professors are

most likely to seek involvement outside their

home field (Klein 1996; Pierce 1999), we control for authors professional age (years since

PhD) and its square. We also control for

authors productivity and visibility in the field,

as these factors influence access to top journals

as well as citations. An authors productivity is

captured by a cumulative, time-varying count

of published journal articles. An authors visibility is captured by a binary variable indicating

whether a scholar has published in ASR or AJS

to date. We also control for each scholars

department prestige using 1995 ratings from

the NRC; we convert the scores to deciles

(ranging from 1 to 10, where higher values

indicate greater prestige) and use regressionbased imputation for unrated departments (predictors include average journal impact, average

citations, percent of faculty publishing in top

journals, and percent of faculty publishing in

JCR-rated journals).

Statistical Approach

Given the structure of our data, we use multilevel modeling to derive estimates. The data

Downloaded from scu.sagepub.com by guest on June 23, 2015

239

Leahey and Moody

are inherently clusteredarticles within scholars, and scholars within departmentsand

thus suitable for multilevel (i.e., hierarchical)

modeling (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002).

Specifically, the level 1 unit is the article, the

level 2 unit is the scholar, and the level 3 unit

is the department. This modeling strategy

accounts for clustering by incorporating both

fixed and random effects.20 Our hypotheses

concern main effects, and we explore two

same-level interactions, but we do not specify

cross-level interactions. The models we estimate (using PROC MIXED in SAS 9.3) can be

expressed as a combination of submodels, one

representing each level:

Level 1 ( articles ) : ln (Yijk ) = 0 jk + jk ARTIC + eijk

Level 2 ( authors ) : 0 jk = 0 k + k AUTH + rjk

Level 3 ( departments ) : 0 k = 0 + DEPT

where there are i articles belonging to j

authors in k departments. The intercept from

the article-level equation (0jk) is not specified

as a fixed effect. Rather, it is allowed to vary

across authors (a random effect), and that variation is then explained using author-level characteristics, such as gender or productivity, in

the author-level (level 2) equation. Similarly,

the intercept from the author-level equation

(0k) is allowed to vary across departments (a

random effect), and that variation is then

explained using department-level characteristics, such as prestige. To estimate the model,

we combine these three equations and rearrange terms to distinguish the fixed and random components:

ln (Yijk ) = 0

+ jk ARTIC + k AUTH + DEPT

= intercept +

all fixed effects

+ eijk + rjk

+ random effects.

The combined equation looks very similar

to single-level regression model, with the

exception of the last term, which is a random

effect associated with authors. This can be

thought of as an error term, or unexplained

variance, associated with the author level. A

random effect at the department level was not

specified.

Results

Among the 1,785 articles of interest, there is

wide variation in both outcomes of interest:

JIF and the number of cumulative citations as

of 2010 (see Table 1). The JIF ranges from 0

(for articles not indexed in the Web of Science)

to 23.87 (the highest impact journal is

Science), and the citation count ranges from 0

to 340. Three-quarters of the articles appear in

a journal that is rated by the Web of Sciences

JCR, and just over a quarter are integrative

according to our binary measure. Authors of

these articles are predominantly men (36 percent are women), in early- to mid-career stage,

with nine published articles; over one-third

have experience publishing in the disciplines

top journals (ASR and AJS). Authors are disproportionately employed at prestigious universities. Within this elite sample, however,

lies some significant variation between integrative and nonintegrative articles (results not

shown). First, integrative pieces are written by

authors who are professionally younger than

authors of nonintegrative work. Second,

integrative articles are more likely to be published in large and prestigious subfields.

Importantly, this may buffer them from the

penalties typically associated with domainspanning work.

Contrary to expectations, subfield integration does not have a curvilinear U-shaped

effect on journal prestige. In fact, novel integration has no significant effect on JIF (see

Table 2), indicating that integrative research is

no less likely to appear in prestigious journals

than nonintegrative research. This suggests

that, despite theoretical reasons to expect difficulty publishing integrative work, there

appears to be no publication-prestige penalty.21 The trend in the popularity of the underlying category or combination, however,

negatively affects impact factor, suggesting

that as topics become more popular, articles

on such topics appear less frequently in top

journals. We also find that sole-authored articles and theory articles tend to be published in

lower-tier journals. Few other variables are

significantly associated with JIF. Exceptions

Downloaded from scu.sagepub.com by guest on June 23, 2015

240

Social Currents 1(3)

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of 1,785 Articles Published by 180 Sociologists in 99 Departments.

Mean

Outcomes variables

Journal impact factor (mean of 1997,

0.86

2000, and 2003 scores)

Cumulative citation count as of 2010

19.34

Article attributes

Novel integration score (percentiles)

24.69

Nominal integration score (binary

0.26

measure)

Year of publication

1995

Trend

0.006

Sole authored

0.23

Theory

0.07

Method

0.06

Theory and method

0.002

Quantitative methods topic

0.03

Subfield(s) productivity

13,055

Subfield(s) prestige

0.68

Author attributesfor last year in data-file

Professional age (2004-PhD year)

8.91

Productivity (number of articles

8.79

published)

Ever published in ASR or AJS

0.37

(yes = 1, no = 0)

Gender (female = 1, male = 0)

0.36

Department attributes

NRC rating of department prestige

5.85

SD

Percent 0s

Minimum

Maximum

1.02

23.8

23.87

30.68

18.3

340

39.7

73.7a

73.7

1

0

100

1

5.36

0.09

0.42

0.26

0.25

0.05

5,399

77.1

92

93

99.7

97.5

31.7

1985

0.15

0

0

0

0

0

1,149

0

9.65

9.75

9

1

39

69

63

64

2.66

12c

10

2004

1.26

1

1

1

1

1

21,293

1

This is the percent of observations that are nonintegrative, so have a score of 1.

This is the percent of observations with the imputed score of 7, equivalent to percentile score of 1.

This is the percent of observations whose department prestige score was predicted based on their average journal

impact, citations, percent of faculty publishing in top journals and in JCR-rated journals. This predicted value was

imputed.

ASR = American Sociological Review; AJS = American Journal of Sociology; NRC = National Research Council

b

c

include department prestige and author experience publishing in top journals like ASR and

AJS, demonstrating some effective path

dependency. These results are robust to the

substitution of the binary measure of nominal

integration: The sign and significance of the

coefficient remain the same, and model fit is

comparable.

Consistent with expectations, we find that

integrative research garners a greater number

of citations than non- (and less novel) integrative work. The models presented in Table 3

suggest that even after controlling for

characteristics of authors, departments, and

subfields, articles that are more integrative

receive a greater number of citations. In the

model with all controls (model 3c), the coefficient for novel integration is positive and

significant (+0.005**) and, considering the

scale of the novel integration measure (1 to

100), represents a reasonably sized effect. For

a 10 percent increase in novel integration, an

articles citations increase by 5 percent, and

for a 50 percent increase in novel integration,

an articles citations increase by 25 percent.

Controlling for year of publication and the

Downloaded from scu.sagepub.com by guest on June 23, 2015

241

Leahey and Moody

Table 2. Assessing Risks: Effects on Journal Impact Factor (Multilevel Model Estimates).

Model 2a

Fixed effects

Article attributes

Novel integration scorea,b a,b

Year of publication

Trend

Sole authored

Theory

Method

Theory and method

Quantitative methods topic

Subfield(s) productivity

Subfield(s) prestige

Author attributes

Professional age (years since PhD)b

Professional age2

Productivity (number of articles)b

Ever published in ASR or AJSb

Gender (female = 1, male = 0)

Department attributes

Department prestige (NRC rating)

Intercept

Random effects

Variance of level 1 random effect

Variance of level 2 random effect

Sample size

2 Res log pseudo-likelihood

BIC

Model 2b

Coefficient

SE

0.0008

0.009

0.56*

0.18**

0.21*

0.08

0.02

0.12

0.008****

0.07

0.0006

0.0004

0.26

0.06

0.09

0.12

0.45

0.19

0.005

0.05

19.0*

9.17

0.83***

0.02

0.27***

0.04

1,785

5,019.4

5,029.7

Coefficient

Model 2c

SE

Coefficient

0.0008

0.007

0.47****

0.17**

0.26**

0.06

0.03

0.13

0.0009*

0.06

0.0006

0.005

0.26

0.06

0.09

0.13

0.45

0.18

0.0004

0.05

0.02*

0.0005*

0.009*

0.72***

0.03

0.008 0.02*

0.0002 0.0004****

0.004 0.009*

0.08

0.62***

0.09

0.05

14.36

11.22

0.82***

0.03

0.18***

0.04

1,785

4,977.7

4,988.1

0.0009

0.006

0.47****

0.21***

0.28**

0.05

0.001

0.13

0.0009*

0.06

0.07***

13.09

SE

0.0006

0.005

0.26

0.06

0.09

0.12

0.44

0.18

0.0005

0.05

0.008

0.0002

0.004

0.08

0.09

0.01

10.77

0.82***

0.03

0.14***

0.03

1,785

4,965.8

4,976.2

Note. ASR = American Sociological Review; AJS = American Journal of Sociology; BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion ;

NRC = National Research Council.

a

One-tailed tests (two-tailed otherwise).

b

Time-varying variable.

*p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001. ****p 0.10.

prestige and productivity of subfields, we find

that articles on topics that are increasing in

popularity actually receive fewer citations

(the coefficient for the trend variable is 2.22

and statistically significant). These effects

hold even when we control for journal prestige, arguably the largest determinant of an

articles citation count. To provide a sense of

the size of the effects in model 3c, we provide

predicted value plots in Figure 3 that stratify

integration (x axis) by selected other variables

(different lines spanning data range). For ease

of comparison, we have equated the y axis

range across all panels.

The size of integrations effect is even

more apparent when we substitute in the

binary measure of nominal integration. In

model 3d, the coefficient for nominal integration (+0.41**) demonstrates that integrative

articles receive almost 41 percent more

Downloaded from scu.sagepub.com by guest on June 23, 2015

242

Downloaded from scu.sagepub.com by guest on June 23, 2015

Note. BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion

One-tailed tests (two-tailed otherwise).

b

Time-varying variable.

c

Not significant, removed.

*p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001. ****p 0.10.

Fixed effects

Article attributes

Novel integration score (percentiles)a,b

Nominal integration scorea

Year of publication

Trend

Sole authored

Theory

Method

Theory and method

Quantitative methods topic

Subfield(s) productivity

Subfield(s) prestige

Journal prestige (impact factor)

Author attributes

Professional age (years since PhD)b

Professional age2 (years since PhD)b,c

Productivity (# articles published)b

Ever published in ASR or AJS (yes = 1, no = 0)b

Gender (female = 1, male = 0)

Department Attributes

Department prestige (NRC rating)

Interaction terms

Novel integration score Journal prestige

Novel integration score Trend

Intercept

Random effects

Variance of level 1 random effect (residual)

Variance of level 2 random effect

Sample size

2 Res log pseudo-likelihood

BIC

25.4

133.8***

6.601***

0.23

1.3***

0.24

1,785

8,640.4

8,650.7

0.002

0.01

0.74

0.18

0.27

0.35

1.27

0.53

0.00001

0.16

0.06

SE

0.005**

0.06***

2.29**

0.18

0.96

0.16

2.18****

0.04

0.00004**

0.12

1.28***

Coefficient

Model 3a

1,785

8,644.5

8,654.9

6.62***

1.17***

109.1***

0.04**

0.01

0.49*

0.09

0.005**

0.05***

2.21**

0.15

0.99***

0.12

2.09****

0.12

0.0003**

0.11

1.25***

Coefficient

Model 3b

0.23

0.23

30.4

0.01

0.01

0.22

0.26

0.002

0.02

0.74

0.17

0.27

0.35

0.27

0.53

0.00001

0.16

0.07

SE

0.03

0.01

0.01

0.22

0.26

0.002

0.02

0.74

0.18

0.27

0.35

1.27

0.43

0.00001

0.16

0.07

6.601***

0.23

1.3***

0.24

1,785

8,647.3

8,657.7

108.6***

0.02

0.04**

0.02

0.47*

0.19

0.005**

0.05***

2.22**

0.12

1.01***

0.12

2.11****

0.17

0.00004*

.11

1.24***

SE

30.37

Model 3c

Coefficient

Table 3. Assessing Benefits: Effects on Logged Cumulative Citations (Multilevel Model Estimates).

30.36

0.03

0.01

0.01

0.23

0.26

0.16

0.02

0.75

0.17

0.27

0.35

1.26

0.53

0.00001

0.16

0.07

SE

6.62***

0.23

1.15***

0.23

1,785

8,638.5

8,648.9

108.37***

0.02

0.04**

0.02

0.47*

0.19

0.41**

0.05***

2.27**

0.12

1.00***

0.12

2.08****

0.13

0.00004*

0.11

1.24***

Coefficient

Model 3d

0.04

0.01

0.010

0.22

0.25

0.002

0.02

1.38

0.18

0.27

0.35

1.26

0.53

0.00001

0.16

0.07

SE

0.23

0.22

0.001

0.02

30.0

1,785

8,644.4

8,650.7

6.56***

1.01***

0.005**

0.08***

114.56***

0.06

0.04**

0.012

0.36****

0.04

0.0005

0.06***

6.91***

0.12

1.08***

0.14

1.94

0.07

0.00004*

0.19

1.14***

Coefficient

Model 3e

243

Leahey and Moody

Figure 3. Relative effect of novel integration (x axis) on log citations, compared across selected

variables.

Note. Predicted values from model 3c, Table 3; all models estimated holding other variable at sample mean.

citations than nonintegrative articles.

Comparing models 3c and 3d, we note that

both measures of integration (nominal in

model 3d, and novel in model 3c) reach the

same level of statistical significance, and both

models fit the data well: The Bayesian

Information Criterion (BIC) and log likelihood values are almost indistinguishable (a

0.009 percent difference). Not only domainspanning itself but also the distance between

domains is beneficial.22

The main effect of novel integration varies

by two other variables, which we add in model

3e.23 First, there is a positive and significant

interaction between novel integration and our

trend variable (+0.08*). Because the main

Downloaded from scu.sagepub.com by guest on June 23, 2015

244

Social Currents 1(3)

Figure 4. Effect of novel integration on citations, interacted with subfield popularity trend.

Note. Predicted values from model 3e, plus interaction with trend; all other variables held at sample mean.

effect of trend is negative, this suggests that

integration is more beneficial when the combination is on the rise but is less beneficial when

the combinations popularity is declining.

Figure 4 demonstrates this strong interaction

effect across the range of trend variable values

in our data (0.16 to +1.26). This finding

reflects a general fact about innovation: It is

valuable to be an early mover in novel areas,

but the discipline quickly ignores integrative

work that spans areas that are falling out of

fashion.

Second, we find that the interaction of novel

integration and journal prestige is statistically

significant and positive (+0.005**), suggesting that integrations positive effect on citations is amplified when the article is published

in a prestigious journal (and, intuitively, integrations effect is effectively null when the

article is published in a journal with impact

factor of zero [i.e., in a journal not indexed in

the Web of Science]). Figure 5 provides the

model predicted effects (and 95% CLMs24) for

integration stratified across our observed range

of JIF. Because the intercept effect of JIF is so

large (justifiably so because the impact factor

is calculated from citations), the inset to Figure

5 provides the differences in slope when the

intercepts are equated, to make the comparison

easier to see. The generally positive returns to

integration are even stronger if one is able to

get integrative work published in prestigious

outlets.

Importantly, these findings appear to be

robust to the influence of selection effects.

First, a comparison of our sample with the

population of articles published 19852004

and indexed in SA suggests that a more inclusive sample of articles would be slightly less

integrative: with 22 percent of the population

integrative, compared with 25 percent of our

sample. Including a broader array of scholars

outside elite research universities, who publish in lower-tier journals and garner fewer

citations, would support the effects of integration we document. Second, once we control

for article and subfield characteristics, women

are no longer disadvantaged with regard to

cumulative citations. If anything, we expect

the relationships between gender and these

article and subfield characteristics to be stronger within the more general population of

Downloaded from scu.sagepub.com by guest on June 23, 2015

245

Leahey and Moody

Figure 5. Effect of novel integration on citations, interacted with journal prestige.

Note. Predicted values from model 3e, plus interaction with Journal impact factor; all other variables held at sample

mean.

female sociologists, and thus genders lack of

significance to hold beyond our elite sample.

Third, we crudely mimic the process of selection via publication: The distinction between

unpublished articles (for which we have no

data) and published articles may be akin to the

distinction between low-tier articles and hightier articles. Thus, we respecified our models,

limiting the sample to articles in journals with

a minimum JIF (we tried the median and the

25th percentile); results are robust to this sample adjustment.

These results are also independent of the

classification system that serves as the basis

for our integration measures. Our results rely on

SA classification codes (Appendix B). When

we match these codes with those provided by an

ASA task force on sociological specialty areas

(http://www2.asanet.org/footnotes/septoct05/

fn7.html) and recalculate the nominal and

novel integration scores, there is no change in

the direction or significance of the hypothesized effects (results available upon request).

Data from other sources also support these

findings. First, a list of the most highly cited

ASR articles (Jacobs 2005) reveals that since

1986, 43 percent (3/7) were integrative. This is

high, especially considering that only 26 percent of the ASR articles in our sample are integrative. Second, a number of authors of

sociology Citation Classics commented,

years later, on the integrative nature of their

articles and how it contributed to its visibility

and impact (Leahey & Cain 2013).25 To provide just one example, Wilson (Sociobiology

1975) tied together a great deal of disparate

information acquired by many specialists in

different topics and provided the first synthesis of its kind that cast a lot of already

familiar material in a new, scientifically better

form while suggesting a way to bridge biology

and the social sciences.

Results are also robust to model respecification. We find that integrations effect is not

curvilinear: When we square the novel integration score and add it to the models, it does

not reach statistical significance. This difference between our results and Uzzi and colleagues (2013) may be partly attributable to a

difference in domains (we study subfields,

they study fields) and the sheer number of

domains (we work with 29 sociological subfields, they work with 240+ fields). Once we

control for other influences, we find that

Downloaded from scu.sagepub.com by guest on June 23, 2015

246

Social Currents 1(3)

integrations effect is the same for scholars of

all ages (i.e., the interaction of novel integration with professional age is not statistically

significant). When we add year-squared to the

models, we find that it is statistically significant and negative, suggesting that times positive effect on both citations and impact factor

is not sustainedbut this effect is very small.

Results also obtain for the subsample of soleauthored articles.

Discussion

In this article, we contributed methodologically and theoretically to a sociological understanding of the process of scientific innovation.

We began by introducing a new concept, subfield integration, and arguing for its relevance

to scientific innovation, thereby expanding

previous research on disciplinary integration

(Clemens et al. 1995) and innovation in academic work (Guetzkow et al. 2004; Simonton

1991). We then developed two empirical measures of subfield integration, one of which

improves upon extant measures by incorporating the novelty of the pairing. We drew upon

two bodies of scholarship: one that documents

challenges associated with domain-spanning

and the other that theorizes benefits. We theorized a reconciliation: Challenges may be

apparent in the short term (review stage), and

benefits in the long term (postpublication

stage). Tests of these hypotheses, using data

from a probability sample of sociologists and

multilevel modeling, reveal negligible risks

(integrative articles are no less likely to be

published in low-tier journals) and tangible

rewards (higher citation rates) associated with

subfield integration.

Our lack of support for challenges is likely

attributable to multiple factors. Based on our

sensitivity analyses, we do not think it is attributable to selection. But other explanations may

obtain. One explanation is that we only studied

one possible penalty (being published in a

low-tier journal); perhaps challenges of integration manifest themselves in another way

(e.g., the work takes longer to produce, or

[unobservable in these data], the article is

reframed to fit a single subdisciplinary niche).

A second explanation rests on our incorporation of time: We expected penalties to be

incurred early on (in the review process), but

perhaps they manifest later, even after publication. For example, an integrative article may

be the prototypical flash in the pan that

receives a lot of attention initially but fails to

accrue a steady stream of followers. Extensions

of this work with time-sensitive citation data

could assess this possibility. Perhaps the third

explanation, which rests on the uniqueness of

sociology, is most likely. Scholars in a field as

diverse as sociology may be particularly

skilled at targeting their work for the intended

audience26, and editors and reviewers in this

field may even expect such integration, given

the permeable boundaries between sociological subfields that scholars commonly bridge

(Moody 2004). Recent editors of the flagship

sociology journal (ASR) have indicated that

they value subfield integration. A former editor argued that one of the principal functions

of a general sociology journal is to enhance

the cross-fertilization of otherwise disparate

specialties . . . [and to] . . . serve as a counterweight against undue fragmentation and segmentation in the discipline (Jacobs 2004),

and more recent editors ask reviewers to consider the number of specialty areas an article

contributes to when submitting their recommendation (Roscigno and Hodson 2007).

Once published, however, integrative

research garners a greater number of citations

than non- (or less novel) integrative research.

Importantly, this is not solely a function of its

broad appeal; that is, integrative research does

not receive more citations simply because it

spans productive subfields and thus attracts a

larger audience, as Lamont (1987) and

Clemens et al. (1995) found. Because we control for the level and growth of subfield productivity, our results suggest that integrative

research garners more attention because it is

viewed as more innovative than research that

fits neatly within a single specialty area. We are

confident of this interpretation for two reasons.

Downloaded from scu.sagepub.com by guest on June 23, 2015

247

Leahey and Moody

First, we account for such prospective audiences by including controls for subfield productivity and prestige in the statistical models.

Second, we use two measures of subfield integrationa binary one that captures nominal

integration (simply the spanning of any two

subfields) and a continuous one that captures

novel integration (which considers rare pairings to be more novel)and both are statistically significant and positively related to

citation counts. In fact, the model including

novel integration score fits the data just as well

as the model including nominal integration

score. Because it is not merely the mixing of

areas but also the uniqueness of that mixing

that makes an article more noteworthy to other

researchers, we are confident that it is the novelty of subfield integration that enhances its

usefulness, not merely audience size. A recent

article in Science (Uzzi et al. 2013) corroborates this finding and also suggests such novelty, when combined with convention, is most

predictive of hit article status (having citations in the top 5 percent of the entire

distribution).

Our findings support and extend recombinant innovation theory. As the theory suggests,

published articles that span subfields are more

valued by the scholarly community. But we

also extend this theory in two ways. First, we

make a methodological improvement by constructing a measure integration that considers

the novelty of the pairing, to better tap into

theoretical ideas about the importance of the

relatedness, or cognitive distance, between

subfields (Hargadon 2002; Knorr Cetina 1980;

Poincare [1908] 1952; Weitzman 1998).

Second, we find that not only the rarity of the

combination (at a given point in time) but also

its trajectory matters. Integration matters most

when the combination is increasing in popularity. Authors who aim for noteworthy, highly

cited articles should seek not only to combine

rarely combined subfields but also to choose

combinations that are just beginning to be

explored by others.27

The results of this article speak to broader

trends of specialization in science, particularly

concerns about fragmentation within sociology

(Collins 1994; Davis 1994; Gouldner 1970;

Steinmetz and Chae 2002). Just as Calhoun

(1992) sees focusing on sociology to the exclusion of other social science disciplines as

impoverishing, so might focusing on a single

subfield be detrimental in the long run.

Although research that falls within a single

subfield is no more likely than integrative

research to appear in prestigious journals, it

may in the end garner less attention from the

scholarly community. It is integrative work that

spans subfields, especially rarely spanned subfields, which is truly appreciated by subsequent

scholars. At this point, integrative research is

still rare, but perhaps recognizing its long-term

fruitfulness is a first step to help overcome the

ethnocentric insularity of mainstream sociology (Calhoun 1992).