Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

12 The Dialogue Between Psychoanalysis and Neuroscience: Alienation and Reparation

Transféré par

Maximiliano PortilloTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

12 The Dialogue Between Psychoanalysis and Neuroscience: Alienation and Reparation

Transféré par

Maximiliano PortilloDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

This article was downloaded by: [Gazi University]

On: 18 August 2014, At: 22:59

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer

House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Neuropsychoanalysis: An Interdisciplinary Journal

for Psychoanalysis and the Neurosciences

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rnpa20

The Dialogue between Psychoanalysis and

Neuroscience: Alienation and Reparation

a

Douglas Watt Ph.D.

a

Director of Neuropsychology, Quincy Medical Center, 114 Whitwell Street, Quincy, MA

02169

Published online: 09 Jan 2014.

To cite this article: Douglas Watt Ph.D. (2000) The Dialogue between Psychoanalysis and Neuroscience: Alienation and

Reparation, Neuropsychoanalysis: An Interdisciplinary Journal for Psychoanalysis and the Neurosciences, 2:2, 183-192,

DOI: 10.1080/15294145.2000.10773304

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15294145.2000.10773304

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the Content) contained

in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no

representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of

the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,

and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied

upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall

not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other

liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or

arising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic

reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any

form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://

www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

183

The Dialogue between Psychoanalysis and

Neuroscience: Alienation and Reparation

Downloaded by [Gazi University] at 22:59 18 August 2014

Douglas Watt (Boston)

The irony regarding the historical alienation of psychoanalysis and neuroscience, of which virtually everyone is aware, is that Freud started out as a very

competent neurologist who made several important

contributions to the neurological literature of his time,

including work on aphasia. His "Project for a Scientific Psychology" (1895) was his attempt to give psychoanalytic metapsychology the firm grounding in

neuroscience that Freud thought critical to its scientific

validity. Virtually everyone is also aware that the Project failed simply because the neuroscience of Freud's

day did not have the concepts to provide any such

grounding. The Project ended up being a kind of backwards construction, speculating about largely undiscovered brain processes that would be isomorphic with

the psychological principles of consciousness and unconsciousness that Freud was intuitively developing.

Despite this important starting point, psychoanalysis and neuroscience gradually became virtual adversaries during the second half of the twentieth century.

This happened after decades of hegemony of psychoanalysis in American psychiatry departments, in the

context of a fundamental conceptual split between

psychiatry and neurology mostly organized around the

now fortunately outdated distinction between "functional" and' 'organic." Although psychiatry and neurology have finally moved into an increasingly

productive dialogue over the last two decades, there

has been a much more limited movement toward respectful dialogue between psychoanalysis and neuroscience, and precious few of those limited initiatives

have come from the neuroscience side of the fence.

Only very recently have such notables as Kandel

Douglas Watt is Director of Neuropsychology, Quincy Medical Center; Instructor in Neurology/Psychiatry, Boston University School of Medicine.

I This paper was presented as the closing address to the First International Neuro-Psychoanalysis Congress (London, July 2000).

(1999) suggested that perhaps neuroscience could now

reach a new kind of accommodation with psychoanalysis. However, the attitude of many in clinical neuroscience is that psychoanalysis is irrelevant, if it is not

just plain wrong, while experimental neuroscience

(still more allied with behavioral principles) perhaps

sees psychoanalysis as both dead and discredited, with

bridging not only irrelevant but distasteful. Many in

clinical neuroscience and neuropsychiatry still believe

deeply in core psychodynamic ideas, but public statements to that effect are often deemed risky, and particularly inadvisable when dealing with nonclinical

neuroscientists, who quickly move away, and stay

away. Representatives of the view that psychoanalysis

is totally outdated bunk include Paul Churchland (neurophilosopher and author of the well-regarded connectionist manifesto, The Engine of Reason, the Seat of

the Soul, 1996) and Michael Alan Taylor (editor-inchief of the excellent clinical neuroscience journal

Neuropsychiatry, Neuropsychology and Behavioral

Neurology). "Freud bashing" has become as fashionable as the early, grandiose visions of psychoanalysis

once were, and the pendulum has not swung back toward the reasonable middle in any meaningful sense.

More troublesome is the fact that few outside

psychoanalysis seem to understand that psychoanalysis is a sprawling and heterogeneous discipline, hardly

the monolithic and rigid set of doctrines that are so

often presented in the media as "Freudian psychoanalysis." As a body of thought and practice psychoanalysis contains nearly every position one could possibly

embrace on many technical and metapsychological issues, and somewhere else in the literature the opposite

of that position as well. Thus, any neuroscientist painting a broad brushstroke image of psychoanalysis, characterizing it in terms of consistent and rigid doctrines,

would reveal a fundamental ignorance about psychoanalysis, its history, literature, and technical practice.

Downloaded by [Gazi University] at 22:59 18 August 2014

184

As a measure of the dynamic nature of the evolution

of psychoanalysis from the beginning, Freud's thinking was constantly evolving and developing. Continued conflict and heterogeneity have defined the fruitful

expansion of Freud's original ideas through concerted

efforts on the part of decades of clinicians and theorists wor king to redress errors and conceptual holes

in Freud's thinking.

Since alienations typically have two sides, we

might look at this the way a couple's therapist might

examine a failed relationship, as an interactive process

with contributions from both parties. From one side

of the border psychoanalysis was guilty of abandoning

the constructive intent in Freud's Project, while neuroscience contributed to the failure by publicly ignoring

and often privately caricaturing the insights contained

in key psychoanalytic concepts such as transference

and the repetition compulsion (Freud, 1914). Where

these omissions were not in evidence, there was an

even more basic avoidance of topics relating to emotion and consciousness/unconsciousness altogether.

Psychoanalysis, following Freud's lead of disowning

his original efforts to ground metapsychology in neuroscience, then retreated into "splendid" isolation,

with little investment in empirical research or bridge

building to disciplines at its borders. Instead, there was

a reification of metapsychology that in my judgment

has cost psychoanalysis dearly, in terms of its scientific credibility and in terms of its potential growth.

Although there were important revisions to the classical core Freudian doctrine (e.g., in object relations

theory and ego psychology, self and relational theories) psychoanalytic metapsychology still lacks the

neuroscientific foundation and cross-validation that

Freud had originally intended. Along with the disciplinary isolation and the defensive management of its

borders, these trends set the stage for the profound

discrediting and isolation that psychoanalysis endured

in the context of "biological revolution" in psychiatry, particularly in the United States.

Together, these mutually defensive postures by

psychoanalysis and neuroscience-of discrediting, devaluing, and mutual avoidance-guaranteed that few

synthetic conceptualizations had any chance of flowering in the arid desert between these two disciplines.

A landmar k article that marked a potential for movement toward consilience, and a potential softening of

decades of formal hostilities, was David Galin's

(1974) article linking topographical concepts of repression (and other metapsychological notions) with

cortical lateralization. Sadly, this article, although

opening up numerous avenues for synthesis, generated

Douglas Watt

no upsurge in fundamental research on the borders of

psychoanalysis and neuroscience, that a number of us

might have hoped for. The mantle was not taken up

by the broader psychoanalytic community, and psychiatry wanted a divorce; it had no need for psychodynamics anymore anyway, as it had discovered

"monoamaine tweaking" and it liked its new toys,

and the increased esteem associated with its' 'remedicalization." There have been a few notable but lonely

exceptions, such as the work of Howard Shevrin

(1996) and several others who have been quietly pursuing questions empirically for many years, often with

faint-hearted support from the analytic community,

and at best a bemused tolerance (if that) from neuroscience colleagues.

A stubborn positivism in much of neuroscience

has prevented questions such as emotion and consciousness from being viewed as neuroscientifically

respectable until quite recently. In this context, we

have seen a renaissance of neuroscientific interest in

both consciousness and emotion, with two major contributors to those subjects being Antonio Damasio

(1999) and Jaak Panksepp (1998). However, as Panksepp has pointed out, behaviorism didn't die, it simply

went into behavioral neuroscience, where the focus is

largely on the ultra-fine-grained level of analysis, with

a fundamental neglect of large-scale-system properties

such as emotion. This neglect has been informed by

four basic assumptions:

1. There is a certain kind of left-hemisphere bias in

which large-scale system properties are not as attractive as the minutiae of fine-grained detail.

2. There is the belief that animals are probably not

sentient creatures and therefore that they do not

have emotions in the sense of feelings (as opposed

to emotional behaviors).

3. Likewise, there is the belief that consciousness is

most certainly not a neuroscientifically meaningful

domain of study in animals, in agreement with

Thomas Nagel's supposition that one can never

know at all what it feels like to be a bat (although

only a few neuroscientists would even know who

Nagel was or what he thought).

4. There is the assumption that fundamental relationships between emotion and consciousness do not

exist, because these are orthogonal processes.

Clearly, these four assumptions are not shared

by all in neuroscience, particularly those coming from

clinical neuroscience, who by and large would disagree with most if not all four of these assumptions.

Downloaded by [Gazi University] at 22:59 18 August 2014

Alienation and Reparation

Most encouraging over the past five years or so

has been increasing interest in a neuroscience of emotion ("affective neuroscience"). Concurrent with this

there has been a strong suggestion (generated notably

by Panksepp and Damasio) for the central heuristic

that a neuroscience of emotion has to be one of the

keystones in the arch for a neuroscience of consciousness-a proposition that, of course, Freud himself

strongly endorsed. Unfortunately, psychoanalysis has

been virtually alone and quite isolated in its interest

in the fundamental connections between consciousness and emotion, so that there has been precious little

scientific traffic at the intersection of these topics until

recently. But in just the last two years, we have seen

the publication of two landmark works on consciousness and emotion, one of them from Antonio Damasio

(1999) and the other from Jaak Panksepp (1998). Damasio's theoretical synthesis, in which core consciousness arises from the correlation of body (protoself) and

world mappings, in second order mapping structures,

under the constant guidance of emotion (see Watt,

2000, for extensive review) is fundamentally congruent with basic conceptions concerning the ego in psychoanalysis. I Jaak Panksepp' s careful study in animals

of the chemoarchitectures and distributed networ ks involved in the prototype affective states gives us an

empirical grounding for a science of emotional meaning (see Watt, 1999, for extended review). Jaak's work

gives us a general roadmap for investigating how cortical encodings might link to the prototype states, to

generate the vast panoply of emotional meaning and

emotional associations.

It seems clear to me that these two major works

at the intersection of affective neuroscience and consciousness studies are also intrinsically bridge building

between psychoanalysis and neuroscience, even

though that was not a primary intent of either author.

Mark Solms's work has been instrumental in building

momentum toward a more respectful dialogue between

neuroscience and psychoanalysis, and his summary of

classical psychoanalytic conceptions of affect in this

journal have given neuroscientists a concise and easily

digested text from which they can make judgments

about the potential congruence between psychoanalytic concepts and emerging affective neuroscience

I However, the concept of the ego in psychoanalysis is unfortunately

so multidimensional as to elude any simple definition-this itself being a

potential topic for a whole essay. Blanck and Blanck (1979) have suggested

that careful review of the multiple meanings of "ego" reveals that this

concept subsumes many functions under the rubric of a global organizing

or meaning-making process, rendering it broadly synonymous with almost

all psychical (or higher neurological) activity. This may be a very helpful,

or quite trivial, clarification, depending on one's predilections.

185

concepts (see also Neuro-Psychoanalysis, Vol. 1, No.

1). Solms (1997) has also opened up wide avenues for

discussion between the neuroscience of dreaming and

REM sleep and psychoanalytic theories of dreaming

(see Neuro-Psychoanalysis, Vol. 1, No.2, and the ongoing discussion in this issue).

My hope would be that these landmark works

by Damasio and Panksepp signal that neuroscience is

inching away from the myopic focus on an isolated

cortex and moving (albeit ambivalently) toward a future neuroscience of the whole person. Such a neuroscience must have rich interdigitation with the science

of personal meanings that psychoanalysis has attempted to be, for better or worse, for so many decades. Although Damasio, (1999) expresses optimism

that we are seeing the beginning of a true paradigm

shift, we shall have to wait and see whether or not

these important theoretical contributions trickle down

to influence basic neuroscience research. Without such

fundamental influence on the course of empirical neuroscientific work, including most particularly the reframing of fundamental hypotheses for experimental

investigation, it is hard to see how any of these seminal

ideas are likely to substantially change the still positivistic and behavioristic climate in much of modern neuroscience. If such paradigm-shifting influence cannot

be more widely disseminated, it is difficult to see how

neuroscience could ever hope to do much justice to the

wisdom of the ages (which is largely about emotion's

primary role in sentience), or ever truly expose the

complex neural foundations for our "ground of being" as sentient creatures. Until both sentience and

emotion are much more fully investigated in this light,

it is hard to imagine how we will ever come to fully

understand these scientific "Holy Grails."

How can one conceptualize both the current

state-of-the-art with respect to our fragile bridges between the disciplines, possible lines of theoretical extrapolation' and future clinical and research directions

that would develop those bridges and deepen the dialogue? To return to the couples therapy metaphor, this

bridge building cannot take place in a climate where

the dialogue is dominated by the question of whether

Freud was right or wrong. Bridge building requires

both sides to give up their old defensive (and offensive) behaviors. Also by definition, bridge building

must eventually lead to some degree of fundamental

conceptual change for both disciplines. The disciplines

have to move toward a middle ground. It is not adequate for psychoanalysis simply to find support for its

metapsychology in the discoveries of neuroscience.

This is still a fundamentally defensive retrenching, and

Downloaded by [Gazi University] at 22:59 18 August 2014

186

not adequate to the task that psychoanalysis has to

accept, namely the slow and painful overhaul of a doctrine-based metapsychology and its evolution into an

empirically grounded, neuroscientifically valid, metapsychology. To balance the scales, neuroscience must

accept not just the existence but the primacy of the

processes that psychoanalysis has been studying for

decades.

This "prescription for treatment" may be offensive to some mainstream analysts, but it is the stiff

price of progress for a discipline that has in the past

sacrificed bridge building and ongoing empirical testing of concepts for preservation of its internal authority structures. Neuroscience has its own growth pains

in terms of the need to accept that there truly are such

things as, for example, defenses against anxiety and

painful affect (there has been some progress, albeit

slow, on those fronts recently). Perhaps even more

difficult, neuroscience will have to find a way to accept

the validity of fundamental process concepts from psychoanalysis, particularly what I would take as the clinical core of psychoanalytic insight, in the intrinsically

related concepts of transference and the repetition

compulsion.

Caveats and Obstacles in the Dialogue between

Two Traditional Adversaries

Psychoanalysis must redress lingering confusion about

the role of insight and what are essentially higher cognitive factors versus the primary role of more affective-interpersonal and attachment-related processes in

the resolution of long-standing characterological structures. Insight alone is not sufficient as an agent of

change, and nor in a strict sense is insight the real goal

of life. The goal instead is a fundamentally euthymic

affective balance in which we have stable, enduring,

and even deepening connections to loved and valued

people, places, and endeavors, with well-modulated,

contained, and context specific activations of the defensive prototype systems of fear and anger that successfully remove or resolve threats, and that do not

dig us in deeper and destroy relationships. Similarly,

insight is either impossible to achieve or it is empty

intellectualization in the context of a primary therapeutic relationship in which the recapitulation of old

historical traumas is not just a negative component of

the transference but a reality, in the absence or failure

of a stable empathic "hold" offered by the analysttherapist. This view may be rejected by some as an

attempt to smuggle the concept of corrective emo-

Douglas Watt

tional experience through the back door. I would want

to reassure everyone that I do not want to smuggle it

in the back door, I want to widen the front door and

bring it right into the foyer. To avoid misunderstanding; I am not suggesting that insight is not important, rather that separation between concepts about

the therapeutic alliance, corrective emotional experience, and empathic holding, on the one hand, and the

traditional emphasis on insight on the other hand, need

to be reconceptualized as complementary outlines of

more affective versus more cognitive processes promoting characterological change, and not competing

conceptions about change agents in the process of

analysis and psychotherapy. However, almost any version of an evolutionarily sophisticated perspective

suggests that we must consider the affective factors as

a primary base on which the cognitive factors can

potentially operate. From the perspective of the two

clusters of affective systems (see table below), real

effective-behavioral change (what analysts have

called structural change) must stem from the experience of emotional safety lessening the activation of

the "organism defensive states" of fear and rage, and

the lessening of separation distress. We do need insight to see what we are doing, where we have been,

and why, but without the safety of an empathic accepting connection where trauma is not happening we

will not be able to take off the character armor no

matter what cognitive working memories we can entertain about our own internal operations.

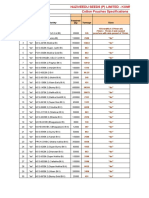

The following table outlines what is currently understood about the prototypic affective states from animal research, and might well form the foundation for

a reworked and modern psychoanalytic theory of

drives and affects. It is worth emphasizing that the

table suggests that Freud was partially right: there are

two large groupings of primary affective states, but

not in terms of a simplistic' 'sex versus aggression"

typology, more along the lines of an "organismic defense system" that would subsume fear and rage, and

an "attachment to conspecifics" system, that would

include play, sexual bonds, attachment, separation distress, and nurturance. There is a third, nonspecific system that Panksepp calls the "seeking" system that

appears to function as a kind of master "gain control"

for virtually all of the other affective states (Panksepp, 1998).

Clearly these important questions and controversies about curative factors in psychotherapy and psychoanalysis have already been discussed in many

places in the psychoanalytic literature (and in the

many psychotherapy literatures). Considerations from

187

Alienation and Reparation

TABLE 1

Distributed Midbrain-Diencephalic-Basal Forebrain Chemoarchitectures for Prototype Emotions.

(From Watt, 1999, extracted from Panksepp, 1998)

Affective Behavior

Structures/Neural Networks

Neuromodulators

Nonspecific Motivational ArousalSeeking & Exploratory

Behavior

Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA) to more

dorsolateral hypothalamic to PAG, with

diffuse mesolimbic and mesocortical

"extensions' ': nucleus accumbens as

crucial basal ganglia processor for

emotional "habit" systems

Medial amygdala to bed nucleus of stria

terminalis (BNST) to anterior and

ventromedial and perifornical

hypothalamic to more dorsal PAG

Lateral and central amygdala to medial and

anterior hypothalamic to more dorsal

PAG to nucleus reticularis pontine

caudalis

BNST and corticomedial amygdala to

preoptic and ventromedial hypothalamus

to ventral PAG

Anterior cingulate to bed nucleus of stria

terminals (BNST) to preoptic

hypothalamic to VTA to ventral PAG

Anterior cingulate/anterior thalamus to

BNST/ventral septum to midline and

dorsomedial thalamus to dorsal preoptic

hypothalamic to dorsal PAG (close to

circuits for physical pain)

Parafascicular/centromedian thalamus,

dorsomedial thalamus, posterior

thalamus, to more dorsal PAG (septum

inhibitory re: play)

DA (+), glutamate (+), many

neuropeptides including opioids,

neurotensin, CCK

Rage/Anger ("Affective Attack")

Downloaded by [Gazi University] at 22:59 18 August 2014

Fear

Sexuality

Nurturance/Maternal Care

Separation Distress/Social Bonding

Play/Joy/Social Affection

?Social Dominance

Substance P (+) (ACh, glutamate

[ +] as nonspecific modulators?)

Glutamate (+), ACTH,

neuropeptides including DBI,

CRF, CCK, alpha MSH, NPY

Steroids (+), vasopressin and

oxytocin, LH-RH, CCK

Oxytocin (+), prolactin (+),

dopamine, opioids both (+) in

moderate amounts

Opioids (- / +) oxytocin (- / + ),

prolactin (- / +) CRF (+) for

separation distress

Glutamate (+), Opiods (+ in small

amounts, - in larger amounts),

muscarine (+), nicotine (+).

Monoamines all appear to be

largely (-) (!?)

Not clear if separate from activation of play

systems and inhibition of fear systems?

Note: This table omits biogenic amines, which are much more nonspecific, and the higher cortical areas in mostly temporal and frontal

regions deeply involved in the further elaborations of emotional processing and emotional meaning, particularly in animals with considerable cortical evolution.

Keys [( -) inhibits prototype, (+) activates prototype] [CCK = choleocystokinin, CRF = corticotrophin releasing factor, ACTH =

adrenocorticotropic hormone, OBI = diazepam binding inhibitor, ACh = acetylcholine, DA = dopamine, MSH = melanocyte stimulating

hormone, NPY = neuropeptide Y]

neurodevelopment (and any version of an evolutionary perspective) suggest that cognitive processes are

an extension of emotional processes just as emotional

processes are an extension of homeostasis and more

primitive foundations for organismic pain and pleasure. Although the constancy and empathic attunement of a competent analyst-therapist may

initially seem a poor second cousin of whatever love

and gratification were missed in the childhood of the

patient, we learn that such empathic attunement is precisely what was absent in our pathogenic traumas, that

such gifts of basic decency and attunement are not

bought, and that instead they constitute the essential

foundations for all competent and good relationships

between conscious creatures. Psychoanalysis offers a

framework in which we reexperience our deepest fears

Downloaded by [Gazi University] at 22:59 18 August 2014

188

and wishes in the transference, appreciate them with

complex working memory and cognitive operators (insight), and lessen the activation of pathologic defenses

that intrinsically limit our empathy for others via distortions of their internal states. Most importantly, psychoanalysis or psychotherapy opens up wide avenues

for creative adaptation previously unavailable in the

context of pathologic defense, because the trauma

does not really happen (of course, these avenues in

turn depend deeply on an identification with the analyst's empathy and attunement). We are unconsciously

convinced that the traumatic repetition will happen,

we do our utmost to make it happen (what Freud called

the "uncanny" nature of the repetition compulsion),

but it doesn't bloom into an emotional reality (a truly

repeated trauma), because the analyst-therapist (we

hope) doesn't do anything traumatic. However, to the

extent that the analyst-therapist is recruited by virtue

of his or her countertransferences to act in the patient's

drama, we have to talk about a partial or complete

failure of the therapy or analysis. This basic perspective, of an alliance characterized by neutrality and

boundaries, nonjudgmental acceptance, low-key

warmth, and deep (not superficial) empathy, is ultimately what enables the consistent focus on fundamental affective issues. These concepts, along with

the process concepts of transference and the repetition

compulsion, constitute an explanatory and treatment

framewor k of unequalled power that neuroscience

needs to build a bridge to. As I said in an earlier paper

(Watt, 1990), if psychoanalysis, despite all its metapsychological convolutions and problems, has provided countless therapists with an explanatory

framework for understanding the complex relationships between affects, cognitions, previous experience, current behavior, and current context, then

psychoanalysis contains vital insights about how the

brain works as a whole that neuroscience badly needs

to appreciate better.

Psychoanalysis must supplement a scientifically

dated metapsychology with concepts from affective

and cognitive neuroscience, and its traditional historical reliance on metapsychological infighting between

different schools and camps must be replaced by a

new reliance on empirical validation of its primary

concepts. Psychoanalysis can no longer afford a defensive posture in which its primary exchange with other

disciplines runs along the lines of attempting to validate Freudian doctrine, as opposed to admitting that

perhaps some of Freud's ideas were simply wrong,

less than optimally framed, or in need of radical overhaul. An authority-driven conservativism must be re-

Douglas Watt

placed by a scientific conservatlvlsm driven by

primary research. This may be hard for some in psychoanalysis to swallow, but psychoanalysis has been

perceived by many in neuroscience (and by those in

other sciences as well) as ideological and either nonempirical or even antiempirical. This perception has

certainly been reinforced by its reliance on a special

jargon that, when abused (due to its high levels of

abstraction and some intrinsic vagueness) seems to

produce mystification and obfuscation of subjective

experience rather than deepening appreciation.

For sure, there are difficulties in advocating a

new empiricism for psychoanalysis. At the very top

of the short list of these would be the manner in which

any technology introduced into the therapeutic situation (in order to monitor the neural systems of the

patient) becomes a fundamental distortion of the analytic framework. Clearly, the mandate to preserve the

framework has been perhaps the strictest of all psychoanalytic mandates, one that we are taught never to

trifle with. 2 However, in an age of increasingly sophisticated noninvasive technologies such as MEG and

functional MRI, psychoanalysis may have to make

some modest concessions on this point in order to get

essential data. Such a new empiricism within psychoanalysis would supply the critical passport of admission to the circle of scientific credibility. Just one

possibility: noninvasive functional monitoring of neural systems in an analytic patient would give us important insights into the long hypothesized laterality

aspects of psychodynamic processes, along with insights into the poorly appreciated vertical integration

of brain systems vis-a-vis psychodynamic variables

(and further insights into the anterior-posterior integration of brain systems).

Although psychoanalysts will rightly wonder if

all of a sudden they are being expected to become

neuroscientists, that is not the prescription here at all.

In fact, the most immediately available avenue for

bridging between the disciplines lies in the clinical

domain in which psychoanalysts spend most of their

professional lives. Simply put, clinical syndromes

might be more fruitfully studied if we adopted a conjoint psychodynamic/developmental and neurobiological point of view (see below, "Bridging Heuristic No.

2 Psychoanalysts have long been taught to resist' 'parameters of technique," and this has at times resulted in a certain inflexibility about the

framewor k, rather than the principle that the treatment frame has to reflect

titration of the level of negative transference that the patient is exposed

to, to ensure the alliance is not swamped by intolerable ambivalence and

anger (worse case scenarios refer to "psychotic transferences"). Again,

these are complex issues with a rich albeit conflicted representation in the

analytic literature.

189

Downloaded by [Gazi University] at 22:59 18 August 2014

Alienation and Reparation

6"). There is increasing evidence that current DSMIV categories are wastebaskets reflecting the clumping

of similar but probably somewhat different disorders

that need to be further unpacked. The variables affecting this heterogeneity probably include significant

variability in the genome among sufferers of a particular disorder, possibly predisposing them to somewhat

different neurobiological derailments under stress. As

we have seen from the experience of dozens of syndromes in neuropsychiatry and neuropsychology,

there are many ways to "crash" a higher brain function, given that these functions depend not on a single

structure or brain region, but on complex distributed

networks. Thus many different lesion locations can

generate very much the same syndrome. This should

be instructive for those in biological psychiatry still

trying to chase down a specific neuroanatomical "lesion," even if only in a functional sense, or any' 'phrenology of neuromodulators"

(the notion that

disruption of a specific neuromodulatory system could

provide an adequate explanation for the syndromes

of DSM-IV). The current heterogeneity (wastebasket

nature) of virtually every syndrome in DSM-IV will

have to be supplanted by a more differentiated nomenclature (derived from much further empirical work)

before we can expect the kind of predictive and treatment successes that we are looking for.

A second crucial variable beyond genotypic variability likely to contribute to the heterogeneity of current DSM-IV categories may be crucial life history

and psychodynamic variables. Clearly genotype, early

history, personality, and characterological issues, precipitating psychological and biological stressors, and

neurobiological derailments are all somehow interdigitated in the epigenetic landscape that generates clinical syndromes. Thus, we probably have a long way to

go to truly understand the interactions of nature and

nurture. But we shall never understand them if we

persist in experimental methodologies that leave out

psychodynamic and early developmental variables and

that therefore are swimming against the current of

modern concepts about development and epigenetic

landscapes. These reductionist research methodologies reflect a lingering separation of mind and body,

of present and past, of nature and nurture. So, psychoanalysis has an opportunity, by virtue of its being a

profoundly developmental clinical discipline, in concert with its neuropsychiatric and neurological and

neuropsychological colleagues, to reexamine the clinical syndromes in DSM-IV. Such research designs

have, to my knowledge, never been implemented, and

they do not require that patients in a prospective re-

search study receive a full analysis. However, they

would instead be informed by careful thinking about

ways in which the psychodynamic and life history

variables could be profitably operationalized and assessed in a consistent fashion (with decent interrater

reliability). Additionally, and just as crucially from the

standpoint of the "couples therapy" metaphor, such

bridging work with clinical neuroscience colleagues

would stop the slow but steady marginalizing of psychoanalytic thought within the medical community,

and would reinvigorate psychiatry.

These powerful concepts (the repetition compulsion and transference) informing an epigenetic perspective on the gradual accretion of human emotional

meanings constitute a very sturdy pillar for bridge

building from the psychoanalytic side of the divide.

One should lead from strength.

Bridging Topics for the Coming

Decade-Initial Heuristic Clusters3

Topics

Group 1: Lateralization, Emotion, and the NaThere have been

ture of the Dynamic Unconscious.

several heuristic lines of speculation about the investment of lateralized right hemisphere processes in the

fundamental phenomena that psychoanalysis has been

concerned with for decades, particularly in terms of

how these processes help us understand the core concept of transference. In two papers (Watt, 1986, 1990),

I reviewed an extensive body of clinical and neuroscientific material suggesting that transference is mediated by right hemisphere processes. We have a long

and well-established empirical tradition documenting

differences in the affective valence of the hemispheres,

in terms of a relatively more dysphoric right hemisphere versus a relatively more euthymic left hemisphere; but this description may not fully characterize

the issue of lateralization with respect to affective valence. I suspect that a better characterization would be

that the right hemisphere may possess our full ambivalence as it were, while the left hemisphere has a kind

of benign, day-to-day, routinized, and more delimited

set of affective representations, yielding a weakly positive (if somewhat superficial) kind of affective valence. Lesions to either system disturb the balance

3 I am referring to these as groups or clusters, as they obviously load

on more than one concept or question, and are an effort to get at several

intrinsically related questions.

Downloaded by [Gazi University] at 22:59 18 August 2014

190

between the two, with the left having crucial inhibitory

functions vis-a-vis the right, while the right hemisphere-as the cortical system in the brain most concerned with the big picture and with global state

functions like emotional, attentional, and executive

functions-is obviously crucial to all of the cortical

elaborations of affect. Although there is talk in some

quarters of a left hemisphere' 'Interpreter" being essential to consciousness, the literature on right hemisphere damage suggests that it might be better termed

a left hemisphere Confabulator.

Lateralization itself is still a perplexing topic,

without an overarching integrative theory, but we do

have tantalizing clues in terms of important neuromodulatory, structural, and even (now) neurodynamic

differences between the hemispheres. There is a large

body of work suggesting that the hemispheres cannot

be characterized simply in terms of verbal versus spatial functions, but rather must be characterized in

terms of a more fundamental "processing style" distinction. Hemispheric relations, both conjunctive and

disjunctive, thus may be a basic ground for mapping

psychoanalytic concepts about the dynamic affective

unconscious onto neural substrates-as David Galin

(1974) argued more than two decades ago. The potentials for bridging in this basic initiative are still largely

unrealized, although many of us who believe in the

fundamental truths of psychodynamics, myself included, have pursued bridging via this particular channel. In any case, the established primacy of the right

hemisphere in generating higher encodings with regard

to both expressive and receptive processing of affect,

interdigitates richly with preliminary formulations

coming from psychoanalytic theorists about transference, other kinds of conscious emotional processing,

and laterality.

Group 2: Transference, Countertransference,

the Repetition Compulsion, Intersubjectivity, and Dynamical Systems Theory. There are unappreciated

congruencies between notions of chaotic attractors in

dynamical systems, the process of intersubjectivity,

and the manner in which people "get to know each

other." Recently, chaos theory has emphasized the notion that ultracomplex systems can have "strange attractors" which cycle the systems into repetitive

states. They have also emphasized that systems have

attractor "basins," and that interacting ultracomplex

systems (any human dyad) are going to find certain

attractor basins in the overall attractor landscape that

both systems move toward repetitively. These cycle

between a relatively limited set of affective states,

Douglas Watt

having an epigenetic landscape that evolves, depending upon the nature of the positive and negative

states activated. As I become a player in your script, in

some way that allows your right hemisphere to define

affectively who I am in relation to you, my own internal set of interactive social-emotional categories for

you also "shakes down," and you find a place in my

drama too. This mutual "shaking down" and activation of emotional categories is what we conventionally

term "getting to know someone"; but we mostly get

to know what each of us "primes out" from the other.

However, there is really no clear leader or follower,

just a kind of curious circular causality, sculpting

semistable attractor states. To the extent that these

scripts repeat old injuries for both of us, cycles of

idealization and traumatic disappointment, we can talk

about transference and countertransference and (once

again) the uncanny nature of the "repetition compulsion." To the extent that we forge an avoidance of

those cycles, and there is mutual empathy, affection,

and support, we can talk about a successful "real"

relationship. But even those, as it turns out, are repetitive of early successes in attachment, recapitulations

of loving and gratifying connections from early in life.

Emotional meaning is thus an intimately personal-historical accretion, as psychoanalysis has rightly emphasized for many decades.

Group 3. The Potential Intersections between

Psychotherapeutic Process, Attachment, Positive Affective States, and the Monoaminergic Therapies: The

Likely Role of Love and Affective Safety in Balancing

the "Symphony of Neuromodulators." It is clear

from Jaak Panksepp's work that neuropeptides and

not the monoamines are probably the great frontier in

psychopharmacology. Neuropeptides have much more

behavioral specificity than classical neuromodulators,

although the evidence also suggests that we will never

find the kind of neat phrenology of neuromodulators

that American psychiatry was looking for in the 1960s

and 1970s, in which a single neuromodulator performs

a single function and yields a single behavior, the disease of which yields a single disorder. We know next

to nothing about the (likely essential) role that good

attachments and positive affective states play in harmonizing what is understood only in the most global

and vague terms as the "symphony of neuromodulators." It is hard to believe that these positive affective

states, activated in good attachments, have anything

but the most central of roles in achieving such a global

and very poorly mapped balance.

191

Alienation and Reparation

Downloaded by [Gazi University] at 22:59 18 August 2014

Group 4: The Nature and Functions of Dreaming. The controversies and complexities of this subject have been the focus of an excellent recent issue

of Neuro-Psychoanalysis (Vol. 1, No.2) and will also

be the focus of an upcoming issue of Behavioral and

Brain Sciences (Vol. 56, No.6). This is obviously still

a deeply controversial and incompletely understood

process, with the spectrum of current positions ranging

from the notion that dreaming is epiphenomenal to

classical psychoanalytic positions on dream interpretation. I would agree with Mark Solms's basic point

that we know much more about the neural substrates

of REM sleep than we do about dreaming (Solms,

1999,2000).

Group 5: The Nature of (Neuro) Development. In many ways, this is the great frontier in neuroscience where all of our theories will be subject to

the most acid of acid tests, and many of them I suspect

will be found wanting. Molecular genetics, neurodevelopment, and neurodynamics are three great frontiers in neuroscience, and their potential interdigitation

is largely uncharted. Clearly, affective processes, and

specifically the vicissitudes of attachment, are primary

drivers in neurodevelopment (the very milieu in which

development takes place, without which the system

cannot develop). Psychoanalysis has been one of the

very few disciplines that has understood this and attempted to pursue this line of inquiry systematically.

However, from a neuroscientific perspective, we know

next to nothing about such profound and foundational

events as the infant's first smiling at mother, or the

infant's first separation cry. These are topics that many

neuroscientists consider not particularly important. Instead, we see legions of researchers chasing down the

subtleties of visual awareness. This may be tantamount

to attempting to learn the complexities of calculus before we have learned how to count on our fingers.

Group 6: The Basic Psychobiological Nature of

Clinical Syndromes, Particularly Depression, Anxiety

Disorders, oCD, Bipolar Disorder, Schizophrenia,

Sociopathy, PTSD and the Dissociative Disorders, and

even the Personality Disorders. We have suffered

too long from thinking that was "either psychodynamic or neuroscientific." This distinction should finally be seen as scientifically unacceptable, and we

should frankly have less tolerance for these kinds of

simplistic and polarizing notions. There is overwhelming evidence that life experience plays a role in OCD,

anxiety, depression, and probably most forms of bipolar disorder. While its role in schizophrenia is less

certain, the roughly 50% concordance for monozygotic twins argues that even in this heyday of genetic

explanations, we need deeper scientific investigation

of the interactions between experience and genetic

predispositions.

Finally, turning once more to the theme that pervades almost every effort to build bridges between our

disciplines, both sides have to move beyond the issue

of whether Freud was "right" or "wrong." This issue, as a primary focus, is just not constructive. For

the record, at least in terms of my own assessment,

Freud was hardly right about everything; in fact, he

was tragically wrong about some important things. But

he did leave an important legacy through trying to

map the rich vicissitudes of human ambivalence. The

fertility of many different clinical and therapeutic

schools of thought owe much to Freud's view that

a deeper appreciation of human "drives" and their

ambivalent nature might be a good starting point for

a fundamental emotional wisdom. In teaching us to

continually appreciate the shades of gray in ourselves

and each other, I would argue that this legacy is the

best way of balancing both the earlier Ernest Jones

style of idealizing Freud and the now popular Freudbashing. It is a pity that Freud himself seems to understand in terms of the more empathic shades of gray

that his work taught us to respect more deeply. I cannot

imagine that our current range of concepts concerning

emotional interaction and internal psychological processes would have anything resembling their present

depth without Freud, even though some of that depth

may have come from those of Freud's followers who

struggled with the many limitations in his original formulations. But isn't that how we make progress anyway? We still have to admit that science (and culture)

exists and advances only because we stand on the shoulders of giants.

References

Blanck, G., & Blanck, R. (1979), Ego Psychology, Vol. 2.

New York: Columbia University Press.

Churchland, P. (1996), The Engine of Reason, the Seat of

the Soul. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Damasio, A. (1999), The Feeling of What Happens. Body

and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness. New

York: Harcourt Brace.

Freud, S. (1895), Project for a scientific psychology. Standard Edition, 1:281-391. London: Hogarth Press, 1966.

- - - (1914), Remembering, repeating and working

through. Standard Edition, 12:145-156. London: Hogarth Press, 1958.

Downloaded by [Gazi University] at 22:59 18 August 2014

192

Galin, D. (1974), Implications for psychiatry of left and

right cerebral specialization. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry,

31 :572-583.

Kandel, E. R. (1999), Biology and the future of psychoanalysis: A new intellectual framework for psychiatry revisited. Amer. J. Psychiatry, 156(4):505-524.

LeDoux, J. (1996), The Emotional Brain. The Mysterious

Underpinnings of Emotional Life. New York: Simon &

Schuster.

Panksepp, J. (1998), Affective Neuroscience. New York:

Oxford University Press.

Shervin, H., Ed. (1996), Conscious and Unconscious Processes: Psychodynamic, Cognitive, and Neurophysiological Convergence. New York: Guilford Press.

Solms, M. (1997), The Neuropsychology ofDreams: A Clinico-Anatomical Study. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- - - (1999), Commentary on Allan Hobson: The new

neuropsychology of sleep: Implications for psychoanalysis. Neuro-Psychoanal., 1(2): 183-195.

- - - (in press), Dreaming and REM sleep are controlled

by different brain mechanisms. Behav. & Brain Sci.

Douglas Watt

Watt, D. F. (1986), Transference: A right hemisphere

event? An inquiry into the boundary between psychoanalytic metapsychology and neuropsychology. PsychoanaI. & Contemp. Thought, 9(1):43-77.

- - - (1990), Higher cortical functions and the ego: The

boundary between psychoanalysis, behavioral neurology

and neuropsychology. Psychoanal. Psycho 1., 7(4):487527.

- - - (1999), Emotion and consciousness. Part I. A review of Jaak Panksepp's Affective Neuroscience. J. Consciousness Studies, 6(7): 191-200.

- - - (2000), Emotion and consciousness. Part II. A review of Antonio Damasio's The Feeling of What Happens. J. Consciousness Studies, 7(3):52-73.

Douglas F. Watt, Ph.D.

Director of Neuropsychology

Quincy Medical Center

114 Whitwell Street

Quincy, MA 02169

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- 8 The Affective Neuroscience Personality Scales: Normative Data and ImplicationsDocument14 pages8 The Affective Neuroscience Personality Scales: Normative Data and ImplicationsMaximiliano PortilloPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Understanding Addictive Vulnerability: An Evolving Psychodynamic PerspectiveDocument18 pages1 Understanding Addictive Vulnerability: An Evolving Psychodynamic PerspectiveMaximiliano PortilloPas encore d'évaluation

- 9 The Human Brain and Photographs and DiagramsDocument2 pages9 The Human Brain and Photographs and DiagramsMaximiliano PortilloPas encore d'évaluation

- 4 Response To CommentariesDocument5 pages4 Response To CommentariesMaximiliano PortilloPas encore d'évaluation

- 3 The Concept of The Self and The Self RepresentationDocument18 pages3 The Concept of The Self and The Self RepresentationMaximiliano PortilloPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Editors' IntroductionDocument3 pages1 Editors' IntroductionMaximiliano PortilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Deep MethodDocument13 pagesDeep Methoddarkelfist7Pas encore d'évaluation

- FACT SHEET KidZaniaDocument4 pagesFACT SHEET KidZaniaKiara MpPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 14ADocument52 pagesChapter 14Arajan35Pas encore d'évaluation

- HUAWEI P8 Lite - Software Upgrade GuidelineDocument8 pagesHUAWEI P8 Lite - Software Upgrade GuidelineSedin HasanbasicPas encore d'évaluation

- Answer The Statements Below by Boxing The Past Perfect TenseDocument1 pageAnswer The Statements Below by Boxing The Past Perfect TenseMa. Myla PoliquitPas encore d'évaluation

- For Printing Week 5 PerdevDocument8 pagesFor Printing Week 5 PerdevmariPas encore d'évaluation

- Atlantean Dolphins PDFDocument40 pagesAtlantean Dolphins PDFBethany DayPas encore d'évaluation

- Governance Whitepaper 3Document29 pagesGovernance Whitepaper 3Geraldo Geraldo Jr.Pas encore d'évaluation

- IAB Digital Ad Operations Certification Study Guide August 2017Document48 pagesIAB Digital Ad Operations Certification Study Guide August 2017vinayakrishnaPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Point Scale PowerpointDocument40 pages5 Point Scale PowerpointMíchílín Ní Threasaigh100% (1)

- WRAP HandbookDocument63 pagesWRAP Handbookzoomerfins220% (1)

- ViTrox 20230728 HLIBDocument4 pagesViTrox 20230728 HLIBkim heePas encore d'évaluation

- The Development of Poetry in The Victorian AgeDocument4 pagesThe Development of Poetry in The Victorian AgeTaibur Rahaman0% (1)

- WIKADocument10 pagesWIKAPatnubay B TiamsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Mangaid CoDocument50 pagesMangaid CoFk Fit RahPas encore d'évaluation

- Exam Questions AZ-304: Microsoft Azure Architect Design (Beta)Document9 pagesExam Questions AZ-304: Microsoft Azure Architect Design (Beta)Deepa R NairPas encore d'évaluation

- Case 3 GROUP-6Document3 pagesCase 3 GROUP-6Inieco RachelePas encore d'évaluation

- Soal Pas Myob Kelas Xii GanjilDocument4 pagesSoal Pas Myob Kelas Xii GanjilLank BpPas encore d'évaluation

- Apush Leq Rubric (Long Essay Question) Contextualization (1 Point)Document1 pageApush Leq Rubric (Long Essay Question) Contextualization (1 Point)Priscilla RayonPas encore d'évaluation

- 61 Point MeditationDocument16 pages61 Point MeditationVarshaSutrave100% (1)

- Earnings Statement: Hilton Management Lane TN 38117 Lane TN 38117 LLC 755 Crossover MemphisDocument2 pagesEarnings Statement: Hilton Management Lane TN 38117 Lane TN 38117 LLC 755 Crossover MemphisSelina González HerreraPas encore d'évaluation

- Adrenal Cortical TumorsDocument8 pagesAdrenal Cortical TumorsSabrina whtPas encore d'évaluation

- Latvian Adjectives+Document6 pagesLatvian Adjectives+sherin PeckalPas encore d'évaluation

- Budget ProposalDocument1 pageBudget ProposalXean miPas encore d'évaluation

- Dialogue About Handling ComplaintDocument3 pagesDialogue About Handling ComplaintKarimah Rameli100% (4)

- Research On Goat Nutrition and Management in Mediterranean Middle East and Adjacent Arab Countries IDocument20 pagesResearch On Goat Nutrition and Management in Mediterranean Middle East and Adjacent Arab Countries IDebraj DattaPas encore d'évaluation

- Byron and The Bulgarian Revival Period - Vitana KostadinovaDocument7 pagesByron and The Bulgarian Revival Period - Vitana KostadinovavitanaPas encore d'évaluation

- RulesDocument508 pagesRulesGiovanni MonteiroPas encore d'évaluation

- Cotton Pouches SpecificationsDocument2 pagesCotton Pouches SpecificationspunnareddytPas encore d'évaluation

- SATYAGRAHA 1906 TO PASSIVE RESISTANCE 1946-7 This Is An Overview of Events. It Attempts ...Document55 pagesSATYAGRAHA 1906 TO PASSIVE RESISTANCE 1946-7 This Is An Overview of Events. It Attempts ...arquivoslivrosPas encore d'évaluation