Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Obligations and Contracts

Transféré par

Cnfsr KayceCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Obligations and Contracts

Transféré par

Cnfsr KayceDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

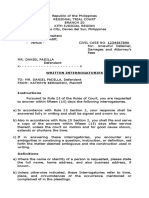

OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS -2ND EXAM

Kristine Confesor

1291-1304- NOVATION

1

2

LICAROS V. GATMAITAN

W/N the MoA between petitioner and respondent is one of assignment of

credit or one of conventional subrogation.

#1 will determine W/N respondent became liable to petitioner under the

promissory note considering that its efficacy is dependent on the

Memorandum of Agreement, the note being merely an annex to the said

memorandum.[6]

An assignment of credit has been defined as the process of transferring the right

of the assignor to the assignee who would then have the right to proceed against

the debtor. The assignment may be done gratuitously or onerously, in which case,

the assignment has an effect similar to that of a sale. [7] On the other hand,

subrogation has been defined as the transfer of all the rights of the creditor to a

third person, who substitutes him in all his rights. It may either be legal or

conventional. Legal subrogation is that which takes place without agreement but

by operation of law because of certain acts. Conventional subrogation is that which

takes place by agreement of parties.[8]

The general tenor of the foregoing definitions of the terms subrogation and

assignment of credit may make it seem that they are one and the same which they

are not. A noted expert in civil law notes their distinctions thus:

Under our Code, however, conventional subrogation is not identical to

assignment of credit. In the former, the debtors consent is necessary;

in the latter it is not required. Subrogation extinguishes the obligation

and gives rise to a new one; assignment refers to the same right which

passes from one person to another. The nullity of an old obligation may

be cured by subrogation, such that a new obligation will be perfectly

valid; but the nullity of an obligation is not remedied by the assignment

of the creditors right to another.[9]

For our purposes, the crucial distinction deals with the necessity of the consent

of the debtor in the original transaction. In an assignment of credit, the consent

of the debtor is not necessary in order that the assignment may fully produce legal

effects.[10] What the law requires in an assignment of credit is not the consent of

the debtor but merely notice to him as the assignment takes effect only from the

time he has knowledge thereof.[11]A creditor may, therefore, validly assign his

credit and its accessories without the debtors consent. [12] On the other hand,

conventional subrogation requires an agreement among the three parties

concerned the original creditor, the debtor, and the new creditor. It is a new

contractual relation based on the mutual agreement among all the necessary

parties. Thus, Article 1301 of the Civil Code explicitly states that (C)onventional

subrogation of a third person requires the consent of the original parties and of the

third person.

The Court of Appeals thus ruled that the MoA never came into effect due to the

failure of the parties to get the consent of Anglo-Asean Bank to the agreement and,

as such, respondent never became liable for the amount stipulated. We agree MoA

is a conventional subrogation which requires the consent of the debtor, AngloAsean Bank, for its validity. We note with approval the following pronouncement of

the CA:

Immediately discernible from above is the common feature of contracts

involving conventional subrogation, namely, the approval of the debtor

to the subrogation of a third person in place of the creditor. That

Gatmaitan and Licaros had intended to treat their agreement as one of

conventional subrogation is plainly borne by a stipulation in their

Memorandum of Agreement, to wit:

WHEREAS, the parties herein have come to an agreement on the

nature, form and extent of their mutual prestations which they now

record

herein with

the

express

conformity

of

the

third

parties concerned (emphasis supplied), which third party is admittedly

Anglo-Asean Bank.

Had the intention been merely to confer on appellant the status of a mere assignee

of appellees credit, there is simply no sense for them to have stipulated in their

agreement that the same is conditioned on the express conformity thereto of

Anglo-Asean Bank. That they did so only accentuates their intention to treat the

agreement as one of conventional subrogation. And it is basic in the interpretation

of contracts that the intention of the parties must be the one pursued (Rule 130,

Section 12, Rules of Court).

W/N AGREEMENT WAS PERFECTED. If the same MoA was actually perfected, then it

cannot be denied that Gatmaitan still has a subsisting commitment to pay Licaros

on the basis of his promissory note. If not, Licaros suit for collection must

necessarily fail. Here, it bears stressing that the subject Memorandum of

Agreement expressly requires the consent of Anglo-Asean to the subrogation. Upon

whom the task of securing such consent devolves, be it on Licaros or Gatmaitan, is

of no significance. What counts most is the hard reality that there has been an

abject failure to get Anglo-Aseans nod of approval over Gatmaitans being

subrogated in the place of Licaros. Doubtless, the absence of such conformity on

the part of Anglo-Asean, which is thereby made a party to the same MoA

prevented the agreement from becoming effective, much less from being a source

of any cause of action for the signatories thereto. [13]

The fact that Anglo-Asean Bank did not give such consent rendered the agreement

inoperative considering that, as previously discussed, the consent of the debtor is

needed in the subrogation of a third person to the rights of a creditor.

xxx

It is true that conventional subrogation has the effect of extinguishing the old

obligation and giving rise to a new one. However, the extinguishment of the old

obligation is the effect of the establishment of a contract for conventional

subrogation. It is not a requisite without which a contract for conventional

subrogation may not be created. As such, it is not determinative of whether or not

a contract of conventional subrogation was constituted.

Moreover, it is of no moment that the subject of the Memorandum of Agreement

was the collection of the obligation of Anglo-Asean Bank to petitioner Licaros under

Contract No. 00193. Precisely, if conventional subrogation had taken place with the

consent of Anglo-Asean Bank to effect a change in the person of its creditor, there

is necessarily created a new obligation whereby Anglo-Asean Bank must now give

payment to its new creditor, herein respondent.

2

GARCIA V. LLAMAS

Novation cannot be presumed. It must be clearly shown either by the express

assent of the parties or by the complete incompatibility between the old and the

new agreements. Petitioner herein fails to show either requirement convincingly;

hence, the summary judgment holding him liable as a joint and solidary debtor

stands.

Petitioner seeks to extricate himself from his obligation as joint and solidary debtor

by insisting that novation took place, either through the substitution of De Jesus as

sole debtor or the replacement of the promissory note by the check. Alternatively,

the former argues that the original obligation was extinguished when the latter,

who was his co-obligor, paid the loan with the check.

The fallacy of the second (alternative) argument is all too apparent. The check

could not have extinguished the obligation, because it bounced upon presentment.

By law,[9] the delivery of a check produces the effect of payment only when it

is encashed.

We now come to the main issue of whether novation took place.

Novation is a mode of extinguishing an obligation by changing its objects or

principal obligations, by substituting a new debtor in place of the old one, or by

subrogating a third person to the rights of the creditor. [10] Article 1293 of the Civil

Code defines novation as follows:

Art. 1293. Novation which consists in substituting a new debtor in the place of the

original one, may be made even without the knowledge or against the will of the

latter, but not without the consent of the creditor. Payment by the new debtor

gives him rights mentioned in articles 1236 and 1237.

In general, there are two modes of substituting the person of the debtor:

(1) expromision and (2) delegacion. In expromision, the initiative for the change

does not come from -- and may even be made without the knowledge of -- the

debtor, since it consists of a third persons assumption of the obligation. As such, it

logically requires the consent of the third person and the creditor. Indelegacion, the

debtor offers, and the creditor accepts, a third person who consents to the

substitution and assumes the obligation; thus, the consent of these three persons

are necessary.[11] Both modes of substitution by the debtor require the consent of

the creditor.[12]

Novation may also be extinctive or modificatory. It is extinctive when an old

obligation is terminated by the creation of a new one that takes the place of the

former. It is merely modificatorywhen the old obligation subsists to the extent that

it remains compatible with the amendatory agreement. [13] Whether extinctive

or modificatory, novation is made either by changing the object or the principal

conditions, referred to as objective or real novation; or by substituting the person

of the debtor or subrogating a third person to the rights of the creditor, an act

known as subjective or personal novation.[14] For novation to take place, the

following requisites must concur:

1) There must be a previous valid obligation.

2) The parties concerned must agree to a new contract.

3) The old contract must be extinguished.

4) There must be a valid new contract.[15]

Novation may also be express or implied. It is express when the new obligation

declares in unequivocal terms that the old obligation is extinguished. It is implied

when the new obligation is incompatible with the old one on every point. [16] The

test of incompatibility is whether the two obligations can stand together, each one

with its own independent existence.[17]

NO NOVATION TOOK PLACE.

The parties did not unequivocally declare that the old obligation had been

extinguished by the issuance and the acceptance of the check, or that the check

would take the place of the note.There is no incompatibility between the

promissory note and the check. As the CA correctly observed, the check had been

issued precisely to answer for the obligation. On the one hand, the note evidences

the loan obligation; and on the other, the check answers for it. Verily, the two can

stand together.

Neither could the payment of interests -- which, in petitioners view,

also constitutesnovation[18] -- change the terms and conditions of the

obligation. Such payment was already provided for in the promissory

note and, like the check, was totally in accord with the terms thereof.

Also unmeritorious is petitioners argument that the obligation was novated by the

substitution of debtors. In order to change the person of the debtor, the old one

must be expressly released from the obligation, and the third person or new debtor

must assume the formers place in the relation.[1

In the present case, petitioner has not shown that he was expressly released from

the obligation, that a third person was substituted in his place, or that the joint

and solidary obligation was cancelled and substituted by the solitary undertaking

of De Jesus.

Plaintiffs acceptance of the bum check did not result in substitution by

de Jesus either, the nature of the obligation being solidary due to the fact that the

promissory note expressly declared that the liability of appellants thereunder is

joint and [solidary.] Reason: under the law, a creditor may demand payment or

performance from one of the solidary debtors or some or all of them

simultaneously, and payment made by one of them extinguishes the obligation. It

therefore follows that in case the creditor fails to collect from one of the

solidary debtors, he may still proceed against the other or others.

OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS -2ND EXAM

Kristine Confesor

Moreover, it must be noted that for novation to be valid and legal, the law requires

that the creditor expressly consent to the substitution of a new debtor.

[23]

Since novation implies a waiver of the right the creditor had before

the novation, such waiver must be express. [24] It cannot be supposed, without clear

proof, that the present respondent has done away with his right to exact fulfillment

from either of the solidary debtors.[25]

More important, De Jesus was not a third person to the obligation. From the

beginning, he was a joint and solidary obligor of the P400,000 loan; thus, he can be

released from it only upon its extinguishment. Respondents acceptance of his

check did not change the person of the debtor, because a joint and solidary obligor

is required to pay the entirety of the obligation.

It must be noted that in a solidary obligation, the creditor is entitled to demand the

satisfaction of the whole obligation from any or all of the debtors. [26] It is up to the

former to determine against whom to enforce collection. [27] Having made himself

jointly and severally liable with De Jesus, petitioner is therefore liable [28] for the

entire obligation.[29]

3

CALIFORNIA BUS LINES V. STATE INVESTMENTS

In this case, the attendant facts do not make out a case of novation. The

restructuring agreement between Delta and CBLI executed onOctober 7, 1981,

shows that the parties did not expressly stipulate that the restructuring

agreement novated the promissory notes. Absent an unequivocal declaration of

extinguishment of the pre-existing obligation, only a showing of complete

incompatibility between the old and the new obligation would sustain a finding

of novation by implication.[59] However, our review of its terms yields no

incompatibility between the promissory notes and the restructuring agreement.

It is clear from the foregoing that the restructuring agreement, instead of

containing provisions absolutely incompatible with the obligations of the judgment,

expressly ratifies such obligations in paragraph 8 and contains provisions for

satisfying them.

8. Except as otherwise modified in this Agreement, the terms and

conditions stipulated in PN Nos. 16 to 26 and 52 to 57 shall continue to

govern the relationship between the parties and that the Chattel

Mortgage over various M.A.N. Diesel Buses with Nos. CM No. 80-39, 8040, 80-41, 80-42, 80-43, 80-44 and CM No. 80-15 as well as the Deed

of Pledge executed by Mr. Llamas shall continue to secure the

obligation until full payment.

There was no change in the object of the prior obligations. The restructuring

agreement merely provided for a new schedule of payments and additional

security in paragraph 6 (c) giving Delta authority to take over the management

and operations of CBLI in case CBLI fails to pay installments equivalent to 60

days. Where the parties to the new obligation expressly recognize the continuing

existence and validity of the old one, there can be no novation.[61] Moreover, this

Court has ruled that an agreement subsequently executed between a seller and a

buyer that provided for a different schedule and manner of payment, to restructure

the mode of payments by the buyer so that it could settle its outstanding

obligation in spite of its delinquency in payment, is not tantamount to novation.

The addition of other obligations likewise did not extinguish the promissory

notes. In Young v. CA[63], this Court ruled that a change in the incidental elements

of, or an addition of such element to, an obligation, unless otherwise expressed by

the parties will not result in its extinguishment. In fine, the RESTRUCTURING

AGREEMENT CAN STAND TOGETHER WITH THE PROMISSORY NOTES.

4

AQUINTEY V. TIBONG

FACTS:

On May 6, 1999, petitioner Agrifina Aquintey filed before the RTC of Baguio City, a

complaint for sum of money and damages against spouses Felicidad and Rico

Tibong. Agrifina alleged that Felicidad had secured loans from her on several

occasions but despite demands, the spouses Tibong failed to pay their outstanding

loan, amounting to P773,000.00 exclusive of interests.

Spouses Tibong admitted that they had secured loans from Agrifina. The proceeds

of the loan were then re-lent to other borrowers at higher interest rates.

they had executed deeds of assignment in favor of Agrifina, and that their debtors

had executed promissory notes in Agrifina's favor.

this resulted in a novation of the original obligation to Agrifina.

by virtue of these documents, Agrifina became the new collector of their debtors;

and the obligation to pay the balance of their loans had been extinguished.

Denied the material averments in paragraphs 2 and 2.1 of the complaint.

While they did not state the total amount of their loans, they declared that they did

not receive anything from Agrifina without any written receipt.

In their Pre-Trial Brief, the spouses Tibong maintained that they have never

obtained any loan from Agrifina without the benefit of a written document.

RTC ISSUES:

Whether or not plaintiff is entitled to her claim of P773,000.00;

Whether or not plaintiff is entitled to stipulated interests in the promissory notes;

and

Whether or not the parties are entitled to their claim for damages.9

The trial court ruled that Felicidad's obligation had not been novated by the deeds

of assignment and the promissory notes executed by Felicidad's borrowers. It

explained that the documents

did not contain any express agreement to novate and extinguish Felicidad's

obligation.

the deeds and notes were separate contracts which could stand alone from the

original indebtedness of Felicidad. Considering, however, Agrifina's admission that

she was able to collect from Felicidad's debtors the total amount of P301,000.00,

this should be deducted from the latter's accountability. Hence, the balance,

exclusive of interests, amounted to P472,000.00.

CA affirmed with modification the decision of the RTC

other than Agrifina's bare testimony that she had lost the promissory notes and

acknowledgment receipts, she failed to present competent documentary evidence

to substantiate her claim that Felicidad had, likewise, borrowed the amounts of

P100,000.00, P34,000.00, and P2,000.00. Of the P637,000.00 total account,

P585,659.00 was covered by the deeds of assignment and promissory notes;

hence, the balance of Felicidad's account amounted to only P51,341.00.

sustained the trial court's ruling that Felicidad's obligation to Agrifina had not been

novated by the deeds of assignment and promissory notes executed in the latter's

favor.

Although Agrifina was subrogated as a new creditor in lieu of Felicidad, Felicidad's

obligation to Agrifina under the loan transaction remained;

there was no intention on their part to novate the original obligation.

the legal effects of the deeds of assignment could not be totally disregarded.

The assignments of credits were onerous, hence, had the effect of payment, pro

tanto, of the outstanding obligation.

The fact that Agrifina never repudiated or rescinded such assignments only shows

that she had accepted and conformed to it.

Consequently, she cannot collect both from Felicidad and her individual debtors

without running afoul to the principle of unjust enrichment.

Agrifina's primary recourse then is against Felicidad's individual debtors on the

basis of the deeds of assignment and promissory notes.

deeds of assignment executed by Felicidad had the effect of payment of her

outstanding obligation to Agrifina in the amount of P585,659.00.

since an assignment of credit is in the nature of a sale, the assignors remained

liable for the warranties as they are responsible for the existence and legality of

the credit at the time of the assignment.

ISSUE

W/N the obligation of respondents to pay the balance of their loans, including

interest, was partially extinguished by the execution of the deeds of assignment in

favor of petitioner, relative to the loans of Edna Papat-iw, Helen Cabang, Antoinette

Manuel, and Fely Cirilo in the total amount of P371,000.00.

HELD:

petitioner had no right to collect from respondents the total amount of

P301,000.00, which includes more than P178,980.00 which respondent Felicidad

collected from Tibong, Dalisay, Morada, Chomacog, Cabang, Casuga, Gelacio, and

Manuel. Petitioner cannot again collect the same amount from respondents;

otherwise, she would be enriching herself at their expense. Neither can petitioner

collect from respondents more than P103,500.00 which she had already collected

from Nimo, Cantas, Rivera, Donguis, Fernandez and Ramirez.

There is no longer a need for the Court to still resolve the issue of whether

respondents' obligation to pay the balance of their loan account to petitioner was

partially extinguished by the promissory notes executed by Juliet Tibong, Corazon

Dalisay, Rita Chomacog, Carmelita Casuga, Merlinda Gelacio and Antoinette

Manuel because, as admitted by petitioner, she was able to collect the amounts

under the notes from said debtors and applied them to respondents' accounts.

Under Article 1231(b) of the New Civil Code, novation is enumerated as one of the

ways by which obligations are extinguished. Obligations may be modified by

changing their object or principal creditor or by substituting the person of the

debtor.

The burden to prove the defense that an obligation has been extinguished by

novation falls on the debtor. The nature of novation was extensively explained in

Iloilo Traders Finance, Inc. v. Heirs of Sps. Oscar Soriano, Jr.,65 as follows:

Novation may either be extinctive or modificatory, much being

dependent on the nature of the change and the intention of the

parties. Extinctive novation is never presumed; there must be an

express intention to novate; in cases where it is implied, the acts of the

parties must clearly demonstrate their intent to dissolve the old

obligation as the moving consideration for the emergence of the new

one. Implied novation necessitates that the incompatibility between

the old and new obligation be total on every point such that the old

obligation is completely superseded by the new one. The test of

incompatibility is whether they can stand together, each one having an

independent existence; if they cannot and are irreconciliable, the

subsequent obligation would also extinguish the first.

An extinctive novation would thus have the twin effects of, extinguishing an

existing obligation and,

creating a new one in its stead. This kind of novation presupposes a confluence of

four essential requisites:

(1) a previous valid obligation; P

(2) an agreement of all parties concerned to a new contract; A

(3) the extinguishment of the old obligation; and E

(4) the birth of a valid new obligation. N

Novation is merely modificatory where the change brought about by any

subsequent agreement is merely incidental to the main obligation (e.g., a change

in interest rates or an extension of time to pay); in this instance, the new

agreement will not have the effect of extinguishing the first but would merely

supplement it or supplant some but not all of its provisions.

Novation which consists in substituting a new debtor (delegado) in the place of the

original one (delegante) may be made even without the knowledge or against the

will of the latter but not without the consent of the creditor. Substitution of the

person of the debtor may be effected

by delegacion, meaning, the debtor offers, and the creditor (delegatario), accepts a

third person who consents to the substitution and assumes the obligation.

OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS -2ND EXAM

Kristine Confesor

Thus, the consent of those three persons is necessary. In this kind of novation, it is

NOT enough to extend the juridical relation to a third person; it is necessary that

the old debtor be released from the obligation, and the third person or new debtor

take his place in the relation. Without such release, there is no novation; the third

person who has assumed the obligation of the debtor merely becomes a co-debtor

or a surety. If there is no agreement as to solidarity, the first and the new debtor

are considered obligated jointly.

In Di Franco v. Steinbaum,

The consideration need not be pecuniary or even beneficial to the

person promising. It is sufficient if it be a loss of an inconvenience,

such as the relinquishment of a right or the discharge of a debt, the

postponement of a remedy, the discontinuance of a suit, or

forbearance to sue.

In City National Bank of Huron, S.D. v. Fuller,71

the theory of novation is that the new debtor contracts with the old

debtor that he will pay the debt, and also to the same effect with the

creditor, while the latter agrees to accept the new debtor for the old. A

novation is not made by showing that the substituted debtor agreed to

pay the debt; it must appear that he agreed with the creditor to do so.

Moreover, the agreement must be based on the consideration of the

creditor's agreement to look to the new debtor instead of the old. It is

not essential that acceptance of the terms of the novation and release

of the debtor be shown by express agreement. Facts and

circumstances surrounding the transaction and the subsequent

conduct of the parties may show acceptance as clearly as an express

agreement, albeit implied.72

We find in this case that the CA correctly found that respondents' obligation to pay

the balance of their account with petitioner was extinguished, pro tanto, by the

deeds of assignment of credit executed by respondent Felicidad in favor of

petitioner.

An assignment of credit is an agreement by virtue of which the owner of a

credit, known as the assignor, by a legal cause, such as sale, dation in payment,

exchange or donation, and without the consent of the debtor, transfers his credit

and accessory rights to another, known as the assignee, who acquires the power to

enforce it to the same extent as the assignor could enforce it against the debtor. It

may be in the form of sale, but at times it may constitute a dation in payment,

such as when a debtor, in order to obtain a release from his debt, assigns to his

creditor a credit he has against a third person.

In Vda. de Jayme v. Court of Appeals,

dacion en pago is the delivery and transmission of ownership of a thing

by the debtor to the creditor as an accepted equivalent of the

performance of the obligation. It is a special mode of payment where

the debtor offers another thing to the creditor who accepts it as

equivalent of payment of an outstanding debt. The undertaking really

partakes in one sense of the nature of sale, that is, the creditor is really

buying the thing or property of the debtor, payment for which is to be

charged against the debtor's obligation. As such, the essential

elements of a contract of sale namely: consent, object certain, and

cause or consideration must be present. In its modern concept, what

actually takes place in dacion en pago is an objective novation of the

obligation where the thing offered as an accepted equivalent of the

performance of an obligation is considered as the object of the contract

of sale, while the debt is considered as the purchase price. In any case,

common consent is an essential prerequisite, be it sale or novation, to

have the effect of totally extinguishing the debt or obligation.76

The transfer of rights takes place upon perfection of the contract, and ownership of

the right, including all appurtenant accessory rights, is acquired by the assignee

who steps into the shoes of the original creditor as subrogee of the latter80 from

that amount, the ownership of the right is acquired by the assignee. The law does

not require any formal notice to bind the debtor to the assignee, all that

the law requires is knowledge of the assignment. Even if the debtor had

not been notified, but came to know of the assignment by whatever

means, the debtor is bound by it. If the document of assignment is public, it is

evidence even against a third person of the facts which gave rise to its execution

and of the date of the latter. The transfer of the credit must therefore be held valid

and effective from the moment it is made to appear in such instrument, and third

persons must recognize it as such, in view of the authenticity of the document,

which precludes all suspicion of fraud with respect to the date of the transfer or

assignment of the credit.81

As gleaned from the deeds executed by respondent Felicidad relative to the

accounts of her other debtors, petitioner was authorized to collect the amounts of

P6,000.00 from Cabang, and P63,600.00 from Cirilo. They obliged themselves to

pay petitioner. Respondent Felicidad, likewise, unequivocably declared that Cabang

and Cirilo no longer had any obligation to her.

Equally significant is the fact that, since 1990, when respondent Felicidad executed

the deeds, petitioner no longer attempted to collect from respondents the balance

of their accounts. It was only in 1999, or after nine (9) years had elapsed that

petitioner attempted to collect from respondents. In the meantime, petitioner had

collected from respondents' debtors the amount of P301,000.00.

While it is true that respondent Felicidad likewise authorized petitioner in the deeds

to collect the debtors' accounts, and for the latter to pay the same directly, it

cannot thereby be considered that respondent merely authorized petitioner to

collect the accounts of respondents' debtors and for her to apply her collections in

partial payments of their accounts. It bears stressing that petitioner, as assignee,

acquired all the rights and remedies passed by Felicidad, as assignee, at the time

of the assignment. Such rights and remedies include the right to collect her

debtors' obligations to her.

Petitioner cannot find solace in the Court's ruling in Magdalena Estates. In that

case, the Court ruled that the mere fact that novation does not follow as a matter

of course when the creditor receives a guaranty or accepts payments from a third

person who has agreed to assume the obligation when there is no agreement that

the first debtor would be released from responsibility. Thus, the creditor can still

enforce the obligation against the original debtor.

In the present case, petitioner and respondent Felicidad agreed that the amounts

due from respondents' debtors were intended to "make good in part" the account

of respondents. Case law is that, an assignment will, ordinarily, be interpreted or

construed in accordance with the rules of construction governing contracts

generally, the primary object being always to ascertain and carry out the intention

of the parties. This intention is to be derived from a consideration of the whole

instrument, all parts of which should be given effect, and is to be sought in the

words and language employed.83

Considering all the foregoing, we find that respondents still have a balance on their

account to petitioner in the principal amount of P33,841.00, the difference

between their loan of P773,000.00 less P585,659.00, the payment of respondents'

other debtors amounting to P103,500.00, and the P50,000.00 payment made by

respondents.

5

The requisites for DACION EN PAGO are: P-D-A

1

there must be a performance of the prestation in lieu of

payment (animo solvendi) which may consist in the

delivery of a corporeal thing or a real right or a credit

against the third person;

2

there must be some difference between the prestation due

and that which is given in substitution (aliud pro alio); and

3

there must be an agreement between the creditor and

debtor that the obligation is immediately extinguished by

reason of the performance of a prestation different from

that due.

All the requisites for a valid dation in payment are present in this case . As gleaned

from the deeds, respondent Felicidad assigned to petitioner her credits "to make

good" the balance of her obligation. Felicidad testified that she executed the deeds

to enable her to make partial payments of her account, since she could not comply

with petitioner's frenetic demands to pay the account in cash. Petitioner and

respondent Felicidad agreed to relieve the latter of her obligation to pay the

balance of her account, and for petitioner to collect the same from respondent's

debtors.

Admittedly, some of respondents' debtors, like Edna Papat-iw, were not able to

affix their conformity to the deeds. In an assignment of credit, however, the

consent of the debtor is not essential for its perfection; the knowledge thereof or

lack of it affecting only the efficaciousness or inefficaciousness of any payment

that might have been made. The assignment binds the debtor upon acquiring

knowledge of the assignment but he is entitled, even then, to raise against the

assignee the same defenses he could set up against the assignor necessary in

order that assignment may fully produce legal effects. Thus, the duty to pay does

not depend on the consent of the debtor. The purpose of the notice is only to

inform that debtor from the date of the assignment. Payment should be made to

the assignee and not to the original creditor.

RICARZE V. CA

Petitioner argues that the substitution of Caltex by PCIB as private complainant at

this late stage of the trial is prejudicial to his defense. He argues that the

substitution is tantamount to a substantial amendment of the Informations which is

prohibited under Section 14, Rule 110 of the Rules of Court.

In the case at bar, the substitution of Caltex by PCIB as private complaint is NOT a

substantial amendment. The substitution did not alter the basis of the charge in

both Informations, nor did it result in any prejudice to petitioner. The documentary

evidence in the form of the forged checks remained the same, and all such

evidence was available to petitioner well before the trial. Thus, he cannot claim

any surprise by virtue of the substitution.

Petitioner next argues that in no way was PCIB subrogated to the rights of Caltex,

considering that he has no knowledge of the subrogation much less gave his

consent to it. Alternatively, he posits that if subrogation was proper, then the

charges against him should be dismissed, the two Informations being defective and

void due to false allegations.

Petitioner was charged of the crime of estafa complex with falsification document.

In estafa one of the essential elements to prejudice of another as mandated by

article 315 of the Revise Penal Code.

The element of to the prejudice of another being as essential element of the felony

should be clearly indicated and charged in the information with TRUTH AND LEGAL

PRECISION.

This is not so in the case of petitioner, the twin information filed against him

alleged the felony committed to the damage and prejudice of Caltex. This

allegation is UNTRUE and FALSE for there is no question that as early as March 24,

1998 or THREE (3) LONG MONTHS before the twin information were filed on June

29, 1998, the prejudice party is already PCIBank since the latter Re-Credit the

value of the checks to Caltex as early as March 24, 1998. In effect, assuming there

is valid subrogation as the subject decision concluded, the subrogation took place

OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS -2ND EXAM

Kristine Confesor

an occurred onMarch 24, 1998 THREE (3) MONTHS before the twin information

were filed.

The phrase to the prejudice to another as element of the felony is limited to the

person DEFRAUDED in the very act of embezzlement. It should not be expanded to

other persons which the loss may ultimately fall as a result of a contract which

contract herein petitioner is total stranger.

In this case, there is no question that the very act of commission of the offense

of September 24, 1997 and October 15, 1997 respectively, Caltex was the one

defrauded by the act of the felony.

In the light of these facts, petitioner submits that the twin information are

DEFECTIVE AND VOID due to the FALSE ALLEGATIONS that the offense was

committed to the prejudice of Caltex when it truth and in fact the one prejudiced

here was PCIBank.

The twin information being DEFECTIVE AND VOID, the same should be dismissed

without prejudice to the filing of another information which should state the

offense was committed to the prejudice of PCIBank if it still legally possible without

prejudicing substantial and statutory rights of the petitioner. [27]

Petitioners argument on subrogation is misplaced. The Court agrees with

respondent PCIBs comment that petitioner failed to make a distinction

between legal and conventional subrogation.

Subrogation is the transfer of all the rights of the creditor to a third person, who

substitutes him in all his rights. [28] It may either be legal or conventional. Legal

subrogation is that which takes place without agreement but by operation of law

because of certain acts.[29] Instances of legal subrogation are those provided in

Article 1302[30] of the Civil Code. Conventional subrogation, on the other hand,

is that which takes place by agreement of the parties. [31] Thus, petitioners

acquiescence is not necessary for subrogation to take place because the instant

case is one of legal subrogation that occurs by operation of law, and without need

of the debtors knowledge.

Contrary to petitioners asseverations, the case of People v. Yu Chai Ho [32] relied

upon by the appellate court is in point. The Court declared

We do not however, think that the fiscal erred in alleging that the commission of

the crime resulted to the prejudice of Wm. H. Anderson & Co. It is true that

originally the International Banking Corporation was the prejudiced party, but Wm.

H. Anderson & Co. compensated it for its loss and thus became subrogated to all

its rights against the defendant (article 1839, Civil Code). Wm. H. Anderson & Co.,

therefore, stood exactly in the shoes of the International Banking Corporation in

relation to the defendant's acts, and the commission of the crime resulted to the

prejudice of the firm previously to the filing of the information in the case. The loss

suffered by the firm was the ultimate result of the defendant's unlawful acts, and

we see no valid reason why this fact should not be stated in the information; it

stands to reason that, in the crime of estafa, the damage resulting therefrom need

not necessarily occur simultaneously with the acts constituting the other essential

elements of the crime.

Thus, being subrogated to the right of Caltex, PCIB, through counsel, has the right

to intervene in the proceedings, and under substantive laws is entitled to

restitution of its properties or funds, reparation, or indemnification.

there had been no transaction or privity of contract between him, on

one hand, and Ms. Picache and respondent, on the other.

The assignment by Ms. Picache of the promissory notes to respondent

was a mere ploy and simulation to effect the unjust enforcement of the

invalid promissory notes and to insulate Ms.Picache from any direct

counterclaims, and he never consented or agreed to the said

assignment.

ISSUE:W/N there was an assignment

no novation/subrogation in the case at bar.

of

credit

and

that

there

was

HELD:

Petitioner asserts the position that

consent of the debtor to the assignment of credit is a basic/essential

element in order for the assignee to have a cause of action against the

debtor. Without the debtors consent, the recourse of the assignee in

case of non-payment of the assigned credit, is to recover from the

assignor.

even if there was indeed an assignment of credit, as alleged by the

respondent, then there had been a novation of the original loan

contracts when the respondent was subrogated in the rights of

Ms. Picache, the original creditor.

ART. 1300. Subrogation of a third person in the rights of the

creditor is either legal or conventional. The former is not

presumed, except in cases expressly mentioned in this

Code; the latter must be clearly established in order that it

may take effect.

ART. 1301. Conventional subrogation of a third person

requires the consent of the original parties and the third

person.

-

According to petitioner, the assignment of credit constitutes

conventional subrogation which requires the consent of the original

parties to the loan contract, namely, Ms. Picache (the creditor) and

petitioner (the debtor); and the third person, the respondent (the

assignee). Since petitioner never gave his consent to the assignment

of credit, then the subrogation of respondent in the rights of

Ms. Picache as creditor by virtue of said assignment is without force

and effect.

The transaction between Ms. Picache and respondent was an assignment of

credit, NOT conventional subrogation, and does not require petitioners

consent as debtor for its validity and enforceability.

An assignment of credit has been defined as an agreement by virtue of which

the owner of a credit/ (known as the assignor)/by a legal cause - such as

sale, dation in payment or exchange or donation/ - and without need of the

debtor's consent/, transfers that credit and its accessory rights to another (known

as the assignee), /who acquires the power to enforce it/to the same extent as the

assignor could have enforced it against the debtor.[20]

On the other hand, subrogation, by definition, is the /transfer of all the rights of

the creditor to a third person/ who substitutes him in all his rights. It may either be

legal or conventional. Legal subrogation is that which takes place without

agreement but by operation of law because of certain acts. Conventional

subrogation is that which takes place by agreement of parties.[21]

Although it may be said that the effect of the assignment of credit is to subrogate

the assignee in the rights of the original creditor, this Court still cannot definitively

rule that assignment of credit and conventional subrogation are one and the same.

Petitioners gripe that the charges against him should be dismissed because the

allegations in both Informations failed to name PCIB as true offended party does

not hold water.

CONVENTIONAL SUBROGATION

ASSIGNMENT OF CREDIT

6

LEDONIO V. CAPITOL

the debtors consent is necessary; requires an agreement among the parties

NOT required; mere notice to debtor; takes effe

DEVELOPMENT

concerned the original creditor, the debtor, and the new creditor.

debtor has knowledge thereof.

FACTS:

extinguishes an obligation and gives rise to a new one

assignment refers to the same right which pass

Herein respondent Capitol Development Corporation filed a complaint for the

another

collection of a sum of money against herein petitioner Edgar Ledonio.

nullity of an old obligation may be cured by subrogation such that the new

but the nullity of an obligation is not remedied by

obligation

will

be

perfectly

valid;

creditors right to another.

CDC alleged that

Ledonio obtained from a Ms. Picache two loans, with the aggregate

Article 1300 of the Civil Code provides that conventional subrogation must be

principal amount ofP60,000.00, and covered by promissory notes duly

clearly established in order that it may take effect. Since it is petitioner who claims

signed by petitioner.

that there is conventional subrogation in this case, the burden of proof rests upon

In the first PN, petitioner promised to pay to the order of

him to establish the same[25] by a preponderance of evidence.[26]

Ms. Picache the

principal

amount

of P30,000.00,

in

monthly

In Licaros v. Gatmaitan,[27] this Court ruled that there was conventional

installments of P3,000.00, with the first monthly installment due on9

subrogation, not just an assignment of credit; thus, consent of the debtor is

January 1989.

required for the effectivity of the subrogation. This Court arrived at such a

In the second promissory note, petitioner again promised to pay to the

conclusion in said case based on its following findings

order of Ms. Picache the principal amount of P30,000.00, with 36%

interest per annum, on 1 December 1988.

We agree with the finding of the Court of Appeals that the

Memorandum of Agreement dated July 29, 1988 was in the nature of a

On 1 April 1989, Ms. Picache executed an Assignment of Credit[7] in favor of

conventional subrogation which requires the consent of the debtor,

CDC, which reads xxx: The foregoing document was signed by two witnesses and

Anglo-Asean Bank, for its validity. We note with approval the following

duly acknowledged by Ms. Picache before a Notary Public also on 1 April 1989.

pronouncement of the Court of Appeals:

Since petitioner did not pay any of the loans covered by the promissory notes

"Immediately discernible from above is the common feature of

when they became due, respondent -- sent petitioner several demand letters.

[8]

contracts involving conventional subrogation, namely, the approval of

Despite receiving the said demand letters, petitioner still failed and refused to

the debtor to the subrogation of a third person in place of the creditor.

settle his indebtedness, thus, prompting respondent to file the Complaint with the

That Gatmaitan andLicaros had intended to treat their agreement as

RTC.

one of conventional subrogation is plainly borne by a stipulation in

their Memorandum of Agreement, to wit:

Ledonio sought the dismissal of the Complaint averring

that respondent had no cause of action against him

"WHEREAS, the parties herein have come to an agreement on the

denied obtaining any loan from Ms. Picache and questioned the

nature, form and extent of their mutual prestations which they now

genuineness and due execution of the promissory notes, for they were

record herein with the express conformity of the third parties

the result of intimidation and fraud; hence, void.

concerned" (emphasis supplied),

OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS -2ND EXAM

Kristine Confesor

which third party is admittedly Anglo-Asean Bank.

Had the intention been merely to confer on appellant the status of a

mere "assignee" of appellee's credit, there is simply no sense for them

to have stipulated in their agreement that the same is conditioned on

the "express conformity" thereto of Anglo-Asean Bank. That they did so

only accentuates their intention to treat the agreement as one of

conventional subrogation. And it is basic in the interpretation of

contracts that the intention of the parties must be the one pursued

(Rule 130, Section 12, Rules of Court).

xxxx

Aside for the 'whereas clause" cited by the appellate court in its

decision, we likewise note that on the signature page, right under the

place reserved for the signatures of petitioner and respondent, there is,

typewritten, the words "WITH OUR CONFORME." Under this notation,

the words "ANGLO-ASEAN BANK AND TRUST" were written by hand. To

our mind, this provision which contemplates the signed conformity of

Anglo-Asean Bank,

taken

together

with

the

aforementioned preambulatoryclause leads to the conclusion that both

parties intended that Anglo-AseanBank should signify its agreement

and conformity to the contractual arrangement between petitioner and

respondent. The fact that Anglo-AseanBank did not give such consent

rendered the agreement inoperative considering that, as previously

discussed, the consent of the debtor is needed in the subrogation of a

third person to the rights of a creditor.

None of the foregoing circumstances are attendant in the present case. The

Assignment of Credit, executed by Ms. Picache in favor of respondent, was a

simple deed of assignment. There is nothing in the said Assignment of Credit

which imparts to this Court, whether literally or deductively, that a conventional

subrogation was intended by the parties thereto. The terms of the Assignment of

Credit only convey the straightforward intention of Ms. Picache to sell, assign,

transfer, and convey to respondent the debt due her from petitioner, as evidenced

by the two promissory notes of the latter, dated 9 November 1988 and 10

November 1988, for the consideration of P60,000.00. By virtue of the same

document, Ms. Picache gave respondent full power to sue for, collect and

discharge, or sell and assign the very same debt. The Assignment of Credit was

signed solely by Ms. Picache, witnessed by two other persons. No reference was

made to securing the conforme of petitioner to the transaction, nor any space

provided for his signature on the said document.

Perhaps more in point to the case at bar is Rodriguez v. Court of Appeals,

which this Court found that

[28]

in

The basis of the complaint is not a deed of subrogation but an

assignment of credit whereby the private respondent became the

owner, not the subrogee of the credit since the assignment was

supported by HK $1.00 and other valuable considerations.

xxxx

The petitioner further contends that the consent of the debtor is

essential to the subrogation. Since there was no consent on his part,

then he allegedly is not bound.

Again, we find for the respondent. The questioned deed of assignment is neither

one of subrogation nor a power of attorney as the petitioner alleges. The deed of

assignment clearly states that the private respondent became an assignee and,

therefore, he became the only party entitled to collect the indebtedness. As a

result of the Deed of Assignment, the plaintiff acquired all rights of the assignor

including the right to sue in his own name as the legal assignee. Moreover, in

assignment, the debtor's consent is not essential for the validity of the assignment

(Art. 1624 in relation to Art. 1475, Civil Code), his knowledge thereof affecting only

the validity of the payment he might make (Article 1626, Civil Code).

Note: the assignment was made in a notarized document; notified through demand

letters sent on registered mail, signed by representatives.

7

VALENZUELA V. KALAYAAN

FACTS: Petitioners claim that there was a valid novation in the present case. They

aver that the CA failed to see that the original contract between the petitioners

and Kalayaan was altered, changed, modified and restructured, as a consequence

of the change in the person of the principal debtor and the monthly amortization to

be paid for the subject property. When they agreed to a monthly amortization of

P10,000.00 per month, the original contract was changed; and Kalayaan

recognized Juliets capacity to pay, as well as her designation as the new debtor.

The original contract was novated and the principal obligation to pay for the

remaining half of the subject property was transferred from petitioners to Juliet.

When Kalayaan accepted the payments made by the new debtor, Juliet, it waived

its right to rescind the previous contract. Thus, the action for rescission filed by

Kalayaan against them, was unfounded, since the contract sought to be rescinded

was no longer in existence.

ISSUE: w/n CA failed to apply to the instant case the pertinent provisions of the

new civil code regarding the principle of novation as a mode of extinguishing an

obligation.

HELD:

In the present case, the nature and characteristics of a contract to sell is

determinative of the propriety of the remedy of rescission and the award of

attorneys fees.

Under a contract to sell, the seller retains title to the thing to be sold until the

purchaser fully pays the agreed purchase price.The full payment is a positive

suspensive condition, the non-fulfillment of which is not a breach of contract, but

merely an event that prevents the seller from conveying title to the purchaser. The

non-payment of the purchase price renders the contract to sell ineffective and

without force and effect.[23] Unlike a contract of sale, where the title to the

property passes to the vendee upon the delivery of the thing sold, in a contract to

sell, ownership is, by agreement, reserved to the vendor and is not to pass to the

vendee until full payment of the purchase price. Otherwise stated, in a contract of

sale, the vendor loses ownership over the property and cannot recover it until and

unless the contract is resolved or rescinded; whereas, in a contract to sell, title is

retained by the vendor until full payment of the purchase price. In the latter

contract, payment of the price is a positive suspensive condition, failure ofwhich is

not a breach but an event that prevents the obligation of the vendor to convey title

from becoming effective.[24]

Since the obligation of respondent did not arise because of the failure of

petitioners to fully pay the purchase price, Article 1191[25] of the Civil Code would

have no application. Article 1191 of the New Civil Code will not apply because it

presupposes an obligation already extant. There can be no rescission of an

obligation that is still non-existing, the suspensive condition not having happened.

The parties contract to sell explicitly provides that Kalayaan shall execute and

deliver the corresponding deed of absolute sale over the subject property to the

petitioners upon full payment of the total purchase price. Since petitioners failed to

fully pay the purchase price for the entire property, Kalayaans obligation to convey

title to the property did not arise. Thus, Kalayaan may validly cancel the contract

to sell its land to petitioner, not because it had the power to rescind the contract,

but because their obligation thereunder did not arise.

Inasmuch as the suspensive condition did not take place, Kalayaan cannot be

compelled to transfer ownership of the property to petitioners.

As regards petitioners claim of novation, we do not give credence to petitioners

assertion that the contract to sell was novated when Juliet was allegedly

designated as the new debtor and substituted the petitioners in paying the balance

of the purchase price.

Novation is the extinguishment of an obligation by the substitution or

change of the obligation by a subsequent one which extinguishes or modifies the

first, either by changing the object or principal conditions, or by substituting

another in place of the debtor, or by subrogating a third person in the rights of the

creditor.[29]

Article 1292 of the Civil Code provides that [i]n order that an obligation

may be extinguished by another which substitutes the same, it is imperative that it

be so declared in unequivocal terms, or that the old and the new obligations be on

every point incompatible with each other. Novation is never presumed. Parties to a

contract must expressly agree that they are abrogating their old contract in favor

of a new one. In the absence of an express agreement, novation takes place only

when the old and the new obligations are incompatible on every point.[30] The test

of incompatibility is whether or not the two obligations can stand together, each

one having its independent existence. If they cannot, they are incompatible and

the latter obligation novates the first.[31]

Thus, in order that a novation can take place, the concurrence of the following

requisites are indispensable:

1)

2)

3)

4)

There

There

There

There

must

must

must

must

be

be

be

be

a previous valid obligation; P

an agreement of the parties concerned to a new contract; A

the extinguishment of the old contract; and E

the validity of the new contract. N

In the instant case, none of the requisites are present. There is only one existing

and binding contract between the parties, because Kalayaan never agreed to the

creation of a new contract between them or Juliet. True, petitioners may have

offered that they be substituted by Juliet as the new debtor to pay for the

remaining obligation. Nonetheless, Kalayaan did not acquiesce to the proposal.

Its acceptance of several payments after it demanded that petitioners pay their

outstanding obligation did not modify their original contract. Petitioners,

admittedly, have been in default; and Kalayaans acceptance of the late payments

is, at best, an act of tolerance on the part of Kalayaan that could not have modified

the contract.

As to the partial payments made by petitioners from September 16, 1994 to

December 20, 1997, amounting to P788,000.00, this Court resolves that the said

amount be returned to the petitioners, there being no provision regarding forfeiture

of payments made in the Contract to Sell. To rule otherwise will be unjust

enrichment on the part of Kalayaan at the expense of the petitioners.

Also, the three percent (3%) penalty interest appearing in the contract is patently

iniquitous and unconscionable as to warrant the exercise by this Court of its judicial

discretion. Article 2227 of the Civil Code provides that [l]iquidated damages,

OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS -2ND EXAM

Kristine Confesor

whether intended as an indemnity or a penalty, shall be equitably reduced if they

are iniquitous or unconscionable. A perusal of the Contract to Sell reveals that the

three percent (3%) penalty interest on unpaid monthly installments (per condition

No. 3) would translate to a yearly penalty interest of thirty-six percent (36%).

Although this Court on various occasions has eliminated altogether the three

percent (3%) penalty interest for being unconscionable,[32] We are not inclined to

do the same in the present case. A reduction is more consistent with fairness and

equity.We should not lose sight of the fact that Kalayaan remains an unpaid seller

and that it has suffered, one way or another, from petitioners non-performance of

its contractual obligations. In view of such glaring reality, We invoke the authority

granted to us by Article 1229[33] of the Civil Code, and as equity dictates, the

penalty interest is accordingly reimposed at a reduced rate of one percent (1%)

interest per month, or twelve percent (12%) per annum,[34] to be deducted from

the partial payments made by the petitioners.

8

ISSUES:

1

2

3

TOMIMBANG V. TOMIMBANG

Whether petitioner's obligation is due and demandable;

Whether respondent is entitled to attorney's fees; and

Whether interest should be imposed on petitioner's indebtedness and,

if in the affirmative, at what rate.

Petitioner contends that the loan is not yet due and demandable because the

suspensive condition the completion of the renovation of the apartment units - has

not yet been fulfilled.

Respondent admits that initially, they agreed that payment of the loan shall be

made upon completion of the renovations. However, respondent claims that during

their meeting with some family members in the house of their brother Genaro

sometime in the second quarter of 1997, he and petitioner entered into a new

agreement whereby petitioner was to start making monthly payments on her loan,

which she did from June to October of 1997. In respondent's view, there was a

novation of the original agreement, and under the terms of their new agreement,

petitioner's obligation was already due and demandable.

Respondent also maintains that when petitioner disappeared from the family

compound without leaving information as to where she could be found, making it

impossible to continue the renovations, petitioner thereby prevented the fulfillment

of said condition. He claims that Article 1186 of the Civil Code, which provides

that the condition shall be deemed fulfilled when the obligor voluntarily prevents

its fulfillment, is applicable to this case.

In his Comment to the present petition, respondent raised for the first time, the

issue that the loan contract between him and petitioner is actually one with a

period, not one with a suspensive condition. In his view, when petitioner began to

make partial payments on the loan, the latter waived the benefit of the

term, making the loan immediately demandable.

HELD: NO MERIT

It is undisputed that herein parties entered into a valid loan contract. The only

question is, has petitioner's obligation become due and demandable? YES.

The evidence on record clearly shows that after renovation of 7-8 apartment units

had been completed, petitioner and respondent agreed that the former shall

already start making monthly payments on the loan even if renovation on the last

unit (Unit A) was still pending. Genaro Tomimbang, the younger brother of herein

parties, testified that a meeting was held among petitioner, respondent, himself

and their eldest sister Maricion, sometime during the first or second quarter of

1997, wherein respondent demanded payment of the loan, and petitioner agreed

to pay. Indeed, petitioner began to make monthly payments from June to October

of 1997 totalling P93,500.00.[8] In fact, petitioner even admitted in her Answer with

Counterclaim that she had started to make payments to plaintiff [herein

respondent] as the same was in accord with her commitment to pay

whenever she was able; x x x

Evidently, by virtue of the subsequent agreement, the parties mutually dispensed

with the condition that petitioner shall only begin paying after the completion of all

renovations. There was, in effect, a modificatory or partial novation, of

petitioner's obligation. Article 1291 of the Civil Code provides, thus:

Art. 1291. Obligations may be modified by:

(1)

Changing their object or principal conditions;

(2)

Substituting the person of the debtor;

(3)

Subrogating a third person in the rights of the creditor.

(Emphasis supplied)

In Iloilo Traders Finance, Inc. v. Heirs of Sps. Soriano,[10] the Court expounded on

the nature of novation, to wit:

Novation may either be extinctive or modificatory, much being

dependent on the nature of the change and the intention of the

parties. Extinctive novation is never presumed; there must be an

express intention to novate; x x x .

An extinctive novation would thus have the twin effects of, first,

extinguishing an existing obligation and, second, creating a new one in

its stead. This kind of novation presupposes a confluence of four

essential requisites: (1) a previous valid obligation; (2) an agreement of

all parties concerned to a new contract; (3) the extinguishment of the

old obligation; and (4) the birth of a new valid obligation. Novation is

merely modificatory where the change brought about by any

subsequent agreement is merely incidental to the main

obligation (e.g., a change in interest rates or an extension of

time to pay); in this instance, the new agreement will not have

the effect of extinguishing the first but would merely

supplement it or supplant some but not all of its provisions. [11]

In Ong v. Bogalbal,[12] the Court also stated, thus:

x x x the effect of novation may be partial or total. There is

partial novation when there is only a modification or change in some

principal conditions of the obligation. It is total, when the obligation is

completely extinguished. Also, the term principal conditions in Article

1291 should be construed to include a change in the period to comply

with the obligation. Such a change in the period would only be a partial

novation since the period merely affects the performance, not the

creation of the obligation.[13]

As can be gleaned from the foregoing, the aforementioned four essential

elements and the requirement that there be total incompatibility between the old

and new obligation, apply only to extinctive novation. In partial novation, only

the terms and conditions of the obligation are altered, thus, the main obligation is

not changed and it remains in force.

Petitioner stated in her Answer with Counterclaim [14] that she agreed and complied

with respondent's demand for her to begin paying her loan, since she believed this

was in accordance with her commitment to pay whenever she was able. Her

partial performance of her obligation is unmistakable proof that indeed

the original agreement between her and respondent had been novated by

the deletion of the condition that payments shall be made only after

completion of renovations. Hence, by her very own admission and partial

performance of her obligation, there can be no other conclusion but that under the

novated agreement, petitioner's obligation is already due and demandable.

9

MILLA V. PEOPLE

Facts:

Respondent Carlo Lopez (Lopez) was the Financial Officer of private respondent,

Market Pursuits, Inc. (MPI). In March 2003, Milla represented himself as a real

estate developer from Ines Anderson Development Corporation, which was

engaged in selling business properties in Makati, and offered to sell MPI a property

therein located. For this purpose, he

showed Lopez a photocopy of (TCT) registered in the name of spouses Farley and

Jocelyn Handog (Sps. Handog), as well as a SPA purportedly executed by the

spouses in favor of Milla.[3] Lopez verified with the Registry of Deeds of Makati and

confirmed that the property was indeed registered under the names of Sps.

Handog. Since Lopez was convinced by Millas authority, MPI purchased the

property for P2 million, issuing Security Bank and Trust Co. (SBTC) Check in the

amount of P1.6 million. After receiving the check, Milla gave Lopez

(1)

a notarized Deed of Absolute Sale executed by Sps.

Handog in favor of MPI and

(2)

an original Owners Duplicate Copy of TCT

Milla then gave Regino Acosta (Acosta), Lopezs partner, a copy of the new TCT No.,

registered in the name of MPI. Thereafter, it tendered in favor of Milla SBTC Check

in the amount ofP400,000 as payment for the balance.[5] Milla turned over TCT No.

218777 to Acosta, but did not furnish the latter with the receipts for the transfer

taxes and other costs incurred in the transfer of the property. This failure to turn

over the receipts prompted Lopez to check with the Register of Deeds, where he

discovered that (1) the Certificate of Title given to them by Milla could not be found

therein; (2) there was no transfer of the property from Sps. Handog to MPI; and (3)

TCT No. 218777 was registered in the name of a certain Matilde M. Tolentino.[6]

Consequently, Lopez demanded the return of the amount of P2 million from Milla,

who then issued Equitable PCI Check Nos. in the amount of P1 million each.

However, these checks were dishonored for having been drawn against insufficient

funds. When Milla ignored the demand letter sent by Lopez, the latter, by virtue of

the authority vested in him by the MPI Board of Directors, filed a Complaint against

the former on 4 August 2003two Informations for Estafa Thru Falsification of Public

Documents were filed against Milla for having committed estafa through the

falsification of the notarized Deed of Absolute Sale and TCT No.

ISSUE:

W/N the principle of novation can exculpate Milla from criminal liability?

No.

Held:

The principle of novation cannot be applied to the case at bar.

Milla contends that his issuance of Equitable PCI Check Nos. 188954 and 188955

before the institution of the criminal complaint against him novated his obligation

to MPI, thereby enabling him to avoid any incipient criminal liability and converting

his obligation into a purely civil one. This argument does not persuade.

The principles of novation cannot apply to the present case as to extinguish his

criminal liability. Milla cites People v. Nery[23] to support his contention that his

issuance of the Equitable PCI checks prior to the filing of the criminal complaint

averted his incipient criminal liability. However, it must be clarified that mere

payment of an obligation before the institution of a criminal complaint does not, on

its own, constitute novation that may prevent criminal liability. This Courts ruling in

Nery in fact warned:

It may be observed in this regard that novation is not one of the means recognized

by the Penal Code whereby criminal liability can be extinguished; hence, the role of

novation may only be to either prevent the rise of criminal liability or to cast doubt

on the true nature of the original petition, whether or not it was such that its

breach would not give rise to penal responsibility, as when money loaned is made

to appear as a deposit, or other similar disguise is resorted to (cf. Abeto vs. People,

90 Phil. 581; Villareal, 27 Phil. 481).

Even in Civil Law the acceptance of partial payments, without further change in the

original relation between the complainant and the accused, can not produce

novation. For the latter to exist, there must be proof of intent to extinguish the

original relationship, and such intent can not be inferred from the mere acceptance

of payments on account of what is totally due.Much less can it be said that the

acceptance of partial satisfaction can effect the nullification of a criminal liability

that is fully matured, and already in the process of enforcement. Thus, this Court

has ruled that the offended partys acceptance of a promissory note for all or part

of the amount misapplied does not obliterate the criminal offense

OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS -2ND EXAM

Kristine Confesor

Further, in Quinto v. People,[25] this Court exhaustively explained the concept of

novation in relation to incipient criminal liability,viz:

Novation is never presumed, and the animus novandi, whether totally or partially,

must appear by express agreement of the parties, or by their acts that are too

clear and unequivocal to be mistaken.

The extinguishment of the old obligation by the new one is a necessary element of

novation which may be effected either expressly or impliedly. The term expressly

means that the contracting parties incontrovertibly disclose that their object in

executing the new contract is to extinguish the old one. Upon the other hand, no

specific form is required for an implied novation, and all that is prescribed by law

would be an incompatibility between the two contracts. While there is really no

hard and fast rule to determine what might constitute to be a sufficient change

that can bring about novation, the touchstone for contrariety, however, would be

an irreconcilable incompatibility between the old and the new obligations.

There are two ways which could indicate, in fine, the presence of novation and

thereby produce the effect of extinguishing an obligation by another which

substitutes the same. The first is when novation has been explicitly stated and

declared in unequivocal terms. The second is when the old and the new obligations

are incompatible on every point. The test of incompatibility is whether or not the

two obligations can stand together, each one having its independent existence. If

they cannot, they are incompatible and the latter obligation novates the first.

Corollarily, changes that breed incompatibility must be essential in nature and not

merely accidental. The incompatibility must take place in any of the essential

elements of the obligation, such as its object, cause or principal conditions thereof;

otherwise, the change would be merely modificatory in nature and insufficient to

extinguish the original obligation.

The changes alluded to by petitioner consists only in the manner of payment.

There was really no substitution of debtors since private complainant merely

acquiesced to the payment but did not give her consent to enter into a new

contract. The appellate court observed:

xxx xxx xxx

The acceptance by complainant of partial payment tendered by the buyer, Leonor

Camacho, does not evince the intention of the complainant to have their

agreement novated. It was simply necessitated by the fact that, at that time,

Camacho had substantial accounts payable to complainant, and because of the

fact that appellant made herself scarce to complainant. (TSN, April 15, 1981, 3132) Thus, to obviate the situation where complainant would end up with nothing,

she was forced to receive the tender of Camacho. Moreover, it is to be noted that

the aforesaid payment was for the purchase, not of the jewelry subject of this case,

but of some other jewelry subject of a previous transaction. (Ibid. June 8, 1981, 1011)

The criminal liability for estafa already committed is then not affected by the

subsequent novation of contract, for it is a public offense which must be

prosecuted and punished by the State in its own conation. (Emphasis supplied.)

[26]

In the case at bar, the acceptance by MPI of the Equitable PCI checks tendered by

Milla could not have novated the original transaction, as the checks were only

intended to secure the return of the P2 million the former had already given him.

Even then, these checks bounced and were thus unable to satisfy his liability.

Moreover, the estafa involved here was not for simple misappropriation or

conversion, but was committed through Millas falsification of public documents, the

liability for which cannot be extinguished by mere novation..

10

HEIRS OF SERVANDO V. GONZALES

HELD:

new obligation extinguishes the prior agreement only when the substitution is

unequivocally declared, or the old and the new obligations are incompatible on

every point. A compromise of a final judgment operates as a novation of the