Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Powdery and Downy Mildews On Greenhouse Crops

Transféré par

adga rwerweTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Powdery and Downy Mildews On Greenhouse Crops

Transféré par

adga rwerweDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Dr. Sharon M.

Douglas

Department of Plant Pathology and Ecology

The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station

123 Huntington Street, P. O. Box 1106

New Haven, CT 06504

Founded in 1875

Putting science to work for society

Phone: (203) 974-8601

Fax: (203) 974-8502

Email: Sharon.Douglas@po.state.ct.us

Website: www.ct.gov/caes

POWDERY AND DOWNY MILDEWS ON GREENHOUSE

CROPS

Although powdery mildew has a long

history in greenhouse production, downy

mildew has recently been the focus of

attention and concern. Both diseases can

contribute to significant economic losses in

many greenhouse floricultural (e.g.,

snapdragons, poinsettias, violas, African

daisy, and zinnias) and vegetable (e.g., basil,

tomatoes, and cucumbers) crops. Although

the two diseases share the name mildew,

they are very different. Powdery mildew

infections reduce crop aesthetics and value

but usually do not result in plant death. In

contrast, downy mildew infections often

result in plant death as well as the loss of

aesthetics.

An understanding of the

differences between these diseases is

important for recognition and successful

management.

white to sparse and gray. Powdery mildew

fungi usually attack young developing

shoots, foliage, stems, and flowers but can

also colonize mature tissues. Symptoms

often first appear on the upper surface of

leaves but can also develop on the lower

surfaces. All aboveground parts of plants

can be infected.

Early symptoms are

variable and can be subtle, appearing as

irregular chlorotic or purple areas or as

necrotic lesions.

These symptoms are

followed by the typical white, powdery

appearance (Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4).

POWDERY MILDEW

SYMPTOMS:

Powdery mildews are easily recognized by

the white, powdery growth of the fungus on

infected portions of the plant host. The

powdery appearance results from the

threadlike strands (hyphae) of the fungus

that grow superficially over the plant surface

and produce chains of spores (conidia).

Colonies vary in appearance from fluffy and

Figure 1. Powdery mildew on torenia.

Atypical symptoms include corky, scab-like

lesions, witches-brooms, twisting and

distortion of newly emerging shoots,

premature leaf coloration and drop, slowed

or stunted growth, and leaf rolling. In rare,

but extreme situations, heavy infections

cause plant death.

CAUSAL

ORGANISMS

AND

DISEASE DEVELOPMENT:

Figure 2.

daisy.

Powdery mildew fungi are obligate

pathogens that require living hosts in order

to complete their life cyclestherefore, they

readily infect healthy, vigorous plants.

Some powdery mildew fungi are host

specific while others are generalists with

many hosts. For example, Sphaerotheca

pannosa var. rosae (syn. Podosphaera

pannosa) is host specific and only infects

rose. In contrast, Erysiphe cichoracearum

var. cichoracearum (syn. Golovinomyces

cichoracearum) can infect many hosts

within

several

families

including

Cucurbitaceae, Asteraceae, Verbenaceae,

and Malvaceae. Therefore, knowing the

identity of a powdery mildew is helpful to

determine the potential for spread to other

crops in a greenhouse.

Powdery mildew on gerbera

Figure 3. Powdery mildew on verbena.

Although diagnosis of powdery mildew is

not difficult, symptoms often escape early

detection. When plants are not periodically

monitored, symptoms that develop on lower

or middle leaves arent discovered until they

are sporulating. This explains reports of

sudden explosions of disease when the

percentage of infected leaves increases from

10% to 70% in one week.

Although powdery mildews have been

recognized for years, many questions about

their biology remain unanswered. Although

the symptoms of powdery mildew diseases

might be similar, the fungi responsible for

them are more diverse and complex than

previous thought. Powdery mildews have

recently been reorganized into five tribes.

This resulted in creating new genera and

eliminating or merging others. The powdery

mildew genera of primary importance to

greenhouse production are Podosphaera,

Erysiphe, Leveillula, Golovinomyces, and

Oidium.

Powdery mildew fungi have relatively

simple life cycles on most ornamentals.

Spores (conidia) are produced singly or in

chains on stalks (conidiophores) (Figure 5).

Conidia are powdery and are readily

disseminated by air currents in the

greenhouse. After conidia land on plant

surfaces, they germinate, penetrate the

tissues, and send food-absorbing projections

(haustoria) into the epidermal cells.

Powdery and downy mildews on greenhouse crops. S. M. Douglas

The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station (www.ct.gov/caes)

Threadlike strands of the fungus (hyphae)

then grow over the surface of the infected

plant part and eventually produce more

conidiophores and conidia.

The time

between when conidia land to when new

conidia are produced can be as short as 72

hrs but is more commonly 5-7 days.

Powdery mildew conidia are unique since

unlike most fungal spores, they do not

require free moisture on plant surfaces in

order to infect.

Figure 4. Powdery mildew colonies on

cucumber transplant.

Figure 5.

Chains of powdery mildew

conidia growing the surface of a cucumber

leaf.

In greenhouses, powdery mildews usually

survive between crops as hyphae or fungal

strands in living crop plants or in weedy

hosts. Under certain circumstances, some

powdery mildew fungi produce small, black,

pepper-like resting structures called

chasmothecia

(formerly

cleistothecia)

(Figure 6). These structures allow the

fungus to survive in the absence of a

suitable host. However, the role of these

resistant structures is probably insignificant

in greenhouse situations since continuous

cropping usually provides a constant source

of living hosts.

Figure 6. Powdery mildew chasmothecia

formed on leaf surface. Chasmothecia are in

different stages of maturity (yellow=

immature; dark brown= mature)

Development of powdery mildew in the

greenhouse is influenced by many

environmental

factors,

including

temperature, relative humidity (RH), light

level, and air circulation. Unfortunately,

greenhouses usually provide optimum levels

for all of these conditions.

Optimum

conditions include moderate temperatures

(68-86 F), high humidities (>95% RH), and

low light intensities or shade. However,

these requirements vary with the specific

powdery mildew fungus.

There is an

inverse relationship between temperature

and RH that influences production and

Powdery and downy mildews on greenhouse crops. S. M. Douglas

The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station (www.ct.gov/caes)

spread of powdery mildew conidia. As

temperatures fall at night, RH increases.

High RH stimulates conidia to germinate

and encourages the production of chains of

conidia. In the morning after sunrise,

temperatures warm and RH levels fall.

These conditions help to dry the chains of

conidia prior to dissemination.

Since

conidia are the primary means for new

infections in the greenhouse, air movement

and circulation in the house are very

important for initiating new infections and

spreading disease. The dry, powdery

conidia

are

easily

dislodged

and

disseminated by air movement from opening

and closing doors and grower activities.

Figure 7. Impatiens with downy mildew.

Note stunted plants and leaves that curl

downwards.

DOWNY MILDEW

SYMPTOMS:

Downy mildews have become increasingly

problematic in the horticultural industry and

are currently causing serious losses in many

floricultural crops. Key factors contributing

to the extent of these losses are delayed

recognition

and

misidentification.

Symptoms first appear as subtle pale-yellow

or light green areas on upper leaf surfaces.

Infected leaves can also curl downward

(Figure 7). On some hosts, downy mildew

can result in irregular, angular lesions that

can easily be confused with damage from

foliar nematodes. In other cases, flower

buds fail to form. Systemic symptoms can

include stunting, leaf distortion and

epinasty,

shortened

internodes,

and

decreases in the quantity and quality of

flowers that are produced. Diagnostic

symptoms gradually develop on the

undersurface of the leaf as the pathogen

grows out of the infected leaf. This growth

appears as a fuzzy, tan-gray-purple-brown

mass (Figure 8).

Symptoms often go

unnoticed until leaves brown, shrivel, and

drop.

Figure 8. Undersurface of impatiens leaf

with abundant downy mildew sporulation

(arrow).

CAUSAL

ORGANISMS

AND

DISEASE DEVELOPMENT:

Downy mildews are fungus-like organisms

or water molds that are more closely

related to Phytophthora and Pythium than to

the powdery mildews. The downy mildew

genera of primary importance to greenhouse

Powdery and downy mildews on greenhouse crops. S. M. Douglas

The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station (www.ct.gov/caes)

crops are Plasmopara and Peronospora.

The host ranges of downy mildew pathogens

vary with species. However, the taxonomy

and host specificity of these mildews is

under revision as new information is

acquired from molecular studies.

Downy mildews, like powdery mildews, are

obligate pathogens that obtain nutrients from

plant hosts. Downy mildews grow locally

and systemically in plants and can escape

detection until conditions are right for

sporulation. They reproduce by forming

sporangiophores and sporangia (sometimes

called conidiophores and conidia) that

develop and grow out of the undersurfaces

of infected leaves. These can resemble

bunches of grapes emerging from stomates

(Figure 9). Each grape is a sporangium

that, depending on species and other factors,

germinates directly to form a germ tube or

forms many zoospores. In either case, free

water on the plant surface is essential for

infection. This is a key difference in the

environmental requirements that distinguish

powdery from downy mildew. If zoospores

are formed, they swim in the water, locate

a host, and infect. As little as 6 hours of leaf

wetness is necessary for infection. Both

sporangia and zoospores can be spread by

overhead irrigation or handling and by fans

and air circulation.

In greenhouses, downy mildews can survive

the off-season as mycelium in overseasoning weeds and host plants. They can

also form thick-walled oospores, which are

resting (survival) structures embedded in

dead leaves and other host tissues. The role

of these resistant structures is probably

insignificant in greenhouse situations since

continuous cropping usually provides a

constant source of living hosts. For some

types of downy mildew (e.g., downy mildew

of cucurbits, blue mold of tobacco),

infections are established by sporangia that

are carried by moist air currents that blow

north from southern regions during the

growing season. Other downy mildews can

be seed-borne.

Figure 9. Downy mildew sporangia on

sporangiophores emerging from the

undersurface of a leaf.

Development of downy mildew in the

greenhouse is influenced by many

environmental

factors

including

temperature, RH, light level, and air

circulation. Optimal temperatures range

from 45-70 F, but these can vary with

species. Humidity levels of 85% or higher

are needed for sporulation and disease

development. For many downy mildew

species, sporangia are produced in the

evening and released into the air the next

morning. Sporangia are spread within the

greenhouse via moist air currents,

contaminated tools, equipment, fingers, and

clothing. Sporangia are short-lived and

become less infective under greenhouse

conditions of high temperature and low

humidity. They are also killed by intense

sunlight. The infection to sporulation cycle

Powdery and downy mildews on greenhouse crops. S. M. Douglas

The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station (www.ct.gov/caes)

can be as short as four days, but is usually

longer, around 7-10 days.

STRATEGIES FOR

MANAGEMENT:

DISEASE

An integrated approach is necessary to

effectively manage powdery and downy

mildews in the greenhouse.

1. Culture Maintain adequate plant spacing to

reduce RH levels in the plant canopy.

This also helps to obtain good coverage

when fungicides are used.

Vent and heat to maintain RH levels

below ~ 93%.

Follow a sound cultural program to

avoid stress (e.g., monitor nutrient

levels, pH, and temperature). Hungry

plants have been found to be more

susceptible to downy mildew.

Water management is essential for

managing downy mildews. It is

especially important to eliminate

conditions that favor leaf wetness early

in the day, since this condition is critical

to downy mildew development. This

can be accomplished by changing

watering practices to reduce the amount

of leaf moisture early in the day (i.e.,

change from overhead irrigation to

spaghetti tubes, soaker hoses, or flood

floors).

2. Sanitation Carefully examine and inspect new

cuttings, seedlings, and plugs upon

arrival. Never accept or use diseased

plant material.

Quarantine new plant material, if

possible. Try to segregate all new plant

shipments from existing plants for the

first several weeks.

All diseased tissues should be removed

as soon as they are detected and

immediately placed in a plastic bag to

avoid carrying infected material through

the house.

All production areas should be

thoroughly cleaned and plant debris

removed between crops and production

cycles.

Control weeds in and around the

greenhouse since they can serve as

reservoirs hosts of downy and powdery

mildews.

3. Scout Scout for disease on a regular schedule

to identify outbreaks before they become

widespread.

With powdery mildew, this typically

involves examining one out of 30 plants

each week. It is helpful to concentrate

on the middle and lower leaves since

infections often start in these leaves.

Once disease is detected, examine one

out of 10 plants every week. Continue

with this schedule until plants are free of

disease for at least three weeks.

Thereafter, resume weekly scouting of

one plant out of 30.

With downy mildew, scout at least once

a week, preferably every 2-3 days. Look

for symptoms on upper surfaces of

leaves and turn leaves over to check for

sporulation. Pay special attention to

plants prone to downy mildew (e.g.,

impatiens, basil, coleus).

3. Resistance Genetic resistance is very effective for

managing powdery and downy mildew

but it is unfortunately of limited

availability for most floricultural crops.

For example, in the Fairway series of

coleus, Fairway Mosaic, Fairway Red

Velvet, and Fairway Salmon Rose

have greater resistance to downy mildew

than Fairway Ruby; in the Festival

series of gerbera daisy, Festival Semi

Double Orange is more resistant to

Powdery and downy mildews on greenhouse crops. S. M. Douglas

The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station (www.ct.gov/caes)

powdery mildew than Festival Dark

Eye Golden Yellow.

4. Biological These products need to be applied as

protectants in order to be effective.

Powdery Mildew:

Bacillus subtilis (Cease, Rhapsody,

Serenade)

Trichoderma harzianum Rifai strain

KRL-AG2 (PlantShield)

Downy Mildew:

Bacillus subtilis (Cease, Rhapsody,

Serenade)

Trichoderma harzianum Rifai strain

KRL-AG2 (PlantShield).

5. Chemical Several factors need to be considered

when selecting fungicides for managing

powdery and downy mildews. Among

these are fungicide classes (MOA-FRAC

Code)

for

resistance

management,

REI,

environmental

parameters (e.g., T, RH), compatibility,

residue, and stage of the crop production

cycle. In some cases, control is targeted

at eradication of existing infections and

protection of healthy tissues. Once

disease is detected, the first sprays

should be aimed at eradication. These

are usually followed by sprays for

protection. The efficacy of specific

compounds can vary significantly with

the pathogen and host. Attention to

spray delivery and coverage is also very

important.

Since pesticide registrations vary with

state, check with the appropriate agency

and consult the label before applying

any pesticide.

Strobilurins [QoI] (Compass O, Cygnus,

Insignia, Heritage)

DMIs (Terraguard, Eagle, Hoist, Strike)

Thiophanates (Clearys 3336, OHP

6672)

Carbamate and Strobilurin (Pageant)

Contacts (*Biorationals):

Bicarbonates (Milstop, Kaligreen) *

Coppers (Camelot, Kocide, Phyton 27)

Hydrogen dioxide (ZeroTol, Oxidate)

Sulfur (Microthiol Disperss)

Oils: Horticultural & Neem (Ultra-Fine

Oil, Triact) *

Soaps (Insecticide Soap) *

Fungicides for Downy Mildew:

Systemics:

Cinnamic Acid Amides (Stature DM)

Phenylamide (Subdue Maxx)

Phosphonates (Aliette, Alude, Vital)

Strobilurins

[QoI]

(Compass

O,

Heritage, Cygnus, Fenstop, and Insignia)

Carboxide and strobilurin (Pageant)

Contacts:

Mancozeb (Protect, Dithane)

Coppers (Kocide, Camelot, Phyton 27)

October 2008

Fungicides for Powdery Mildew:

Systemics:

Powdery and downy mildews on greenhouse crops. S. M. Douglas

The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station (www.ct.gov/caes)

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- 3 Pseudoscience and FinanceDocument11 pages3 Pseudoscience and Financemacarthur1980Pas encore d'évaluation

- Injection Pump Test SpecificationsDocument3 pagesInjection Pump Test Specificationsadmin tigasaudaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Conflict Management and Negotiation - Team 5Document34 pagesConflict Management and Negotiation - Team 5Austin IsaacPas encore d'évaluation

- Thd04e 1Document2 pagesThd04e 1Thao100% (1)

- Community Based Nutrition CMNPDocument38 pagesCommunity Based Nutrition CMNPHamid Wafa100% (4)

- Global Supply Chain Top 25 Report 2021Document19 pagesGlobal Supply Chain Top 25 Report 2021ImportclickPas encore d'évaluation

- Fundamental of Transport PhenomenaDocument521 pagesFundamental of Transport Phenomenaneloliver100% (2)

- Lecture 01 Overview of Business AnalyticsDocument52 pagesLecture 01 Overview of Business Analyticsclemen_angPas encore d'évaluation

- Intgui 1100100014665 EngDocument69 pagesIntgui 1100100014665 Engadga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- Aea 0 CF 2 B 98 DF 06 F 1 DB 7Document4 pagesAea 0 CF 2 B 98 DF 06 F 1 DB 7adga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- Scs BrochureDocument11 pagesScs Brochureadga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- Minimum Requirements Achieving ComplianceDocument2 pagesMinimum Requirements Achieving Complianceadga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- 02 WholeDocument65 pages02 Wholeadga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- 54 D 7 Ba 4 B 0 CF 246475817 C 571Document7 pages54 D 7 Ba 4 B 0 CF 246475817 C 571adga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- Minimum Requirements Achieving ComplianceDocument2 pagesMinimum Requirements Achieving Complianceadga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- Outpatient Consult Request FormDocument1 pageOutpatient Consult Request Formadga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- Asian Cities 1985 (Players Telex)Document8 pagesAsian Cities 1985 (Players Telex)adga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

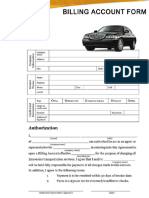

- NJLuxury BillingDocument1 pageNJLuxury Billingadga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- Paper Id-2720147Document4 pagesPaper Id-2720147adga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- Division Standings - Members - TTX - NotepadDocument23 pagesDivision Standings - Members - TTX - Notepadadga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- Suffolk L4266 OK2Document10 pagesSuffolk L4266 OK2adga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- Tender For Cantien 2015Document10 pagesTender For Cantien 2015adga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- The Soz - Trtii &iar ( Oce-'I'V Drainage: Swamp SchemeDocument6 pagesThe Soz - Trtii &iar ( Oce-'I'V Drainage: Swamp Schemeadga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- 171021Document4 pages171021adga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- Written Historical Am) Descriptive Data: O' - '-S, Ouu J - Uy A.BsDocument3 pagesWritten Historical Am) Descriptive Data: O' - '-S, Ouu J - Uy A.Bsadga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- Warren TWP BR General 299218Document8 pagesWarren TWP BR General 299218adga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- Personal Information: Abdullah Omar AL JufryDocument2 pagesPersonal Information: Abdullah Omar AL Jufryadga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- R GR',FL: Yt FIDocument4 pagesR GR',FL: Yt FIadga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- Short Tender Notice For Uid FormDocument8 pagesShort Tender Notice For Uid Formadga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- Khalid PersonalDocument3 pagesKhalid Personaladga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- Treaty V 915Document346 pagesTreaty V 915adga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- Publications 34513412452453452453453245234 R 34523 W 3 FewrtesDocument84 pagesPublications 34513412452453452453453245234 R 34523 W 3 Fewrtesadga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- Kulid3991h 1Document100 pagesKulid3991h 1adga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- Khalid ProfileDocument1 pageKhalid Profileadga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- 8 Sfa 4 FafsefefesrfesrfsvdrfsfsdfvdsDocument452 pages8 Sfa 4 Fafsefefesrfesrfsvdrfsfsdfvdsadga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- Parrag Ian C 201006 PHD Thesis PDFDocument238 pagesParrag Ian C 201006 PHD Thesis PDFadga rwerwePas encore d'évaluation

- MCSE Sample QuestionsDocument19 pagesMCSE Sample QuestionsSuchitKPas encore d'évaluation

- Adressverificationdocview Wss PDFDocument21 pagesAdressverificationdocview Wss PDFabreddy2003Pas encore d'évaluation

- How To Become A Skilled OratorDocument5 pagesHow To Become A Skilled OratorDonain Alexis CamarenaPas encore d'évaluation

- Multigrade Lesson Plan MathDocument7 pagesMultigrade Lesson Plan MathArmie Yanga HernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- Two Steps Individualized ACTH Therapy For West SyndromeDocument1 pageTwo Steps Individualized ACTH Therapy For West SyndromeDrAmjad MirzanaikPas encore d'évaluation

- AgrippaDocument4 pagesAgrippaFloorkitPas encore d'évaluation

- Meter BaseDocument6 pagesMeter BaseCastor JavierPas encore d'évaluation

- Coca-Cola Femsa Philippines, Tacloban PlantDocument29 pagesCoca-Cola Femsa Philippines, Tacloban PlantJuocel Tampil Ocayo0% (1)

- Securingrights Executive SummaryDocument16 pagesSecuringrights Executive Summaryvictor galeanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Coffee in 2018 The New Era of Coffee EverywhereDocument55 pagesCoffee in 2018 The New Era of Coffee Everywherec3memoPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Degrowth - Demaria Schneider Sekulova Martinez Alier Env ValuesDocument27 pagesWhat Is Degrowth - Demaria Schneider Sekulova Martinez Alier Env ValuesNayara SantosPas encore d'évaluation

- TutorialDocument136 pagesTutorialDebadutta MallickPas encore d'évaluation

- Your Song.Document10 pagesYour Song.Nelson MataPas encore d'évaluation

- Keong Mas ENGDocument2 pagesKeong Mas ENGRose Mutiara YanuarPas encore d'évaluation

- IO RE 04 Distance Learning Module and WorksheetDocument21 pagesIO RE 04 Distance Learning Module and WorksheetVince Bryan San PabloPas encore d'évaluation

- Practice Quiz 5 Module 3 Financial MarketsDocument5 pagesPractice Quiz 5 Module 3 Financial MarketsMuhire KevinePas encore d'évaluation

- Part - 1 LAW - 27088005 PDFDocument3 pagesPart - 1 LAW - 27088005 PDFMaharajan GomuPas encore d'évaluation

- Administrative Clerk Resume TemplateDocument2 pagesAdministrative Clerk Resume TemplateManuelPas encore d'évaluation

- LMR - 2023 04 14Document5 pagesLMR - 2023 04 14Fernando ShitinoePas encore d'évaluation

- Werewolf The Apocalypse 20th Anniversary Character SheetDocument6 pagesWerewolf The Apocalypse 20th Anniversary Character SheetKynanPas encore d'évaluation

- Good Governance and Social Responsibility-Module-1-Lesson-3Document11 pagesGood Governance and Social Responsibility-Module-1-Lesson-3Elyn PasuquinPas encore d'évaluation

- Stance AdverbsDocument36 pagesStance Adverbsremovable100% (3)