Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Tax 2 Part 4 Doctrines Only

Transféré par

Nolaida AguirreDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Tax 2 Part 4 Doctrines Only

Transféré par

Nolaida AguirreDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

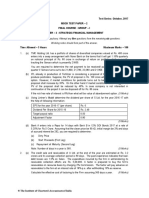

LOCAL AND REAL PROPERTY TAXATION DOCTRINES

Taxation; Delegation of Powers; Power of taxation may be

delegated to local governments on matters of local concern.

The power of taxation x x x may be delegated to local governments

in respect of matters of local concern. This is sanctioned by

immoral practice. By necessary implication, the legislative power to

create political corporations for purposes of local self-government

carries with it the power to confer on such local governmental

agencies the power to tax. x x x The plenary nature of the taxing

power thus delegated, contrary to plaintiff-appellants pretense,

would not suffice to invalidate the said law as confiscatory and

oppressive. In delegating the authority, the State is not limited to

the exact meassure of that which is exercised by itself. When it is

said that the taxing power may be delegated to municipalities and

the like, it is meant taxes there may be delegated such measure of

power to impose and collect taxes as the legislature may deem

expedient. Thus, municipalities may be permitted to tax subjects

which for reasons of public policy the State has not deemed wise to

tax for more general purposes.

Same; Due process; Taking of property without due process of

law may not be passed over under the guise of taxing power,

except when the latter is exercised lawfully.This is not to say

though that the constitutional injunction against deprivation of

property without due process of law may be passed over under the

guise of the taxing power, except when the taking of the property is

in the lawful exercise of the taxing power, as when (1) the tax is for

a public purpose; (2) the rule on uniformity of taxation is observed;

(3) either the person or property taxed is within the jurisdiction of

the government levying the tax; and (4) in the assessment and

collection of certain kinds of taxes notice and opportunity for

hearing are provided.

Same; Same; Delegation of powers; Delegation of taxing power

to local governments may not be assailed on the ground of

double taxation.There is no validity to the assertion that the

delegated authority can be declared unconstitutional on the theory

of double taxation. It must be observed that the delegating authority

specifies the limitations and enumerates the taxes over which local

taxation may not be exercised. x x x Moreover, double taxation, in

general, is not forbidden by our fundamental law, since We have not

adopted as part thereof the injunction against double taxation found

in the Constitution of the United States and some states of the

Union. Double taxation becomes obnoxious only where the taxpayer

is taxed twice for the benefit of the same governmental entity or by

the same jurisdiction for the same purpose, but not in a case where

one tax is imposed by the State and the other by the city of

municipality.

Taxation; A municipal ordinance which imposes a tax of P0.01

for every gallon of soft drinks produced in the municipality

does not partake of a percentage tax.The imposition of a tax

of one centavo (P0.01) on each gallon (128 flued ounces, U.S.) of

11/01/2014

volume capacity on all soft drinks produced or manufactured

under Ordinance No. 27 does not partake of the nature of a

percentage tax on sales, or other taxes in any form based thereon.

The tax is levied on the produce (whether sold or not) and not on

the sales. The volume capacity of the taxpayers production of soft

drinks is considered solely for purposes of determining the tax rate

on the products, but there is no set ratio between the volume of

sales and the amount of the tax.

Same; A municipal tax on soft drinks is not a specific tax.Nor

can the tax levied be treated as a specific tax. Specific taxes are

those imposed on specified articles, such as distilled spirits, wines,

x x x cigars and cigarettes, matches, x x x bunker fuel oil, diesel fuel

oil, cinematographic films, playing cards, saccharine, opium and

other habit-forming drugs. Soft drinks is not one of those specified.

Same; A municipal tax of P0.01 on each gallon of soft drinks

produced is not unfair or oppressive.The tax of one centavo

(P0.01) on each gallon (128 fluid ounces, U.S.) of volume capacity on

all soft drinks, produced or manufactured, or an equivalent of 1

centavos per case, cannot be considered unjust and unfair. An

increase in the tax alone would not support the claim that the tax is

oppressive, unjust and confiscatory. Municipal corporations are

allowed much discretion in determining the rates of imposable

taxes. This is in line with the constitutional policy of according the

widest possible autonomy to local governments in matters of local

taxation, an aspect that is given expression in the Local Tax Code

(PD No. 231, July 1, 1973). Unless the amount is so excessive as to be

prohibitive, courts will go slow in writing off an ordinance as

unreasonable.

Same; Licenses; Municipalities are empowered to impose not

only municipal license but just and uniform taxes for public

purposes.The municipal license tax of P1,000.00 per corking

machine with five but not more than ten crowners x x x imposed on

manufacturers, producers, importers and dealers of soft drinks

and/or mineral waters x x x appears not to affect the resolution of

the validity of Ordinance No. 27. Municipalities are empowered to

impose, not only municipal license taxes upon persons engaged in

any business or occupation but also to levy for public purposes, just

and uniform taxes. The ordinance in question (Ordinance No. 27)

comes within the second power of a municipality. [Pepsi-Cola

Bottling Co. of the Philippines, Inc. vs. Municipality of Tanauan,

Leyte, 69 SCRA 460(1976)]

Taxation; As a general rule, the power to tax is an incident of

sovereignty and is unlimited in its range, acknowledging in its

very nature no limits, so that security against its abuse is to

be found only in the responsibility of the legislature which

imposes the tax on the constituency who are to pay it.As a

general rule, the power to tax is an incident of sovereignty and is

unlimited in its range, acknowledging in its very nature no limits, so

LOCAL AND REAL PROPERTY TAXATION DOCTRINES

that security against its abuse is to be found only in the

responsibility of the legislature which imposes the tax on the

constituency who are to pay it. Nevertheless, effective limitations

thereon may be imposed by the people through their Constitutions.

Our Constitution, for instance, provides that the rule of taxation

shall be uniform and equitable and Congress shall evolve a

progressive system of taxation. So potent indeed is the power that

it was once opined that the power to tax involves the power to

destroy.

Same; Statutory Construction; Since taxation is a destructive

power which interferes with the personal and property rights

of the people and takes from them a portion of their property

for the support of the government, tax statutes must be

construed strictly against the government and liberally in

favor of the taxpayer; But since taxes are what we pay for

civilized society, or are the lifeblood of the nation, the law

frowns against exemptions from taxation and statutes granting

tax exemptions are thus construed strictissimi juris against

the taxpayer and liberally in favor of the taxing authority.

Verily, taxation is a destructive power which interferes with the

personal and property rights of the people and takes from them a

portion of their property for the support of the government.

Accordingly, tax statutes must be construed strictly against the

government and liberally in favor of the taxpayer. But since taxes

are what we pay for civilized society, or are the lifeblood of the

nation, the law frowns against exemptions from taxation and

statutes granting tax exemptions are thus construed stricissimi

juris against the taxpayer and liberally in favor of the taxing

authority. A claim of exemption from tax payments must be clearly

shown and based on language in the law too plain to be mistaken.

Elsewise stated, taxation is the rule, exemption therefrom is the

exception. However, if the grantee of the exemption is a political

subdivision or instrumentality, the rigid rule of construction does

not apply because the practical effect of the exemption is merely to

reduce the amount of money that has to be handled by the

government in the course of its operations.

Same; Local Government Units; The power to tax is primarily

vested in the Congress but in our jurisdiction, it may be

exercised by local legislative bodies, no longer merely by

virtue of a valid delegation but pursuant to direct authority

conferred by the Constitution. The power to tax is primarily

vested in the Congress; however, in our jurisdiction, it may be

exercised by local legislative bodies, no longer merely by virtue of a

valid delegation as before, but pursuant to direct authority

conferred by Section 5, Article X of the Constitution. Under the

latter, the exercise of the power may be subject to such guidelines

and limitations as the Congress may provide which, however, must

be consistent with the basic policy of local autonomy.

11/01/2014

Same; Same; Non-Impairment Clause; Since taxation is the rule

and exemption therefrom the exception, the exemption may be

withdrawn at the pleasure of the taxing authority, the only

exception being where the exemption was granted to private

parties based on material consideration of a mutual nature,

which then becomes contractual and thus covered by the nonimpairment clause of the Constitution.There can be no

question that under Section 14 of R.A. No. 6958 the petitioner is

exempt from the payment of realty taxes imposed by the National

Government or any of its political subdivisions, agencies, and

instrumentalities. Nevertheless, since taxation is the rule and

exemption therefrom the exception, the exemption may thus be

withdrawn at the pleasure of the taxing authority. The only

exception to this rule is where the exemption was granted to

private parties based on material consideration of a mutual nature,

which then becomes contractual and is thus covered by the

nonimpairment clause of the Constitution.

Same; Same; Local Government Code; Words and Phrases;

Fees and Charges, Explained.Section 133 of the LGC

prescribes the common limitations on the taxing powers of local

government units. Needless to say, the last item (item 0 of Sec. 133

of the LGC) is pertinent to this case. The taxes, fees or charges

referred to are of any kind; hence, they include all of these, unless

otherwise provided by the LGC. The term taxes is well understood

so as to need no further elaboration, especially in light of the above

enumeration. The term fees means charges fixed by law or

ordinance for the regulation or inspection of business or activity,

while charges are pecuniary liabilities such as rents or fees

against persons or property.

Same; Same; Same; Since the last paragraph of Section 234 of

the LGC unequivocally withdrew, upon the effectivity of the

LGC, exemptions from payment of real property taxes granted

to natural or juridical persons, including government-owned or

controlled corporations, except as provided in the said

section, and Mactan Cebu International Airport Authority is a

government-owned corporation, it necessarily follows that its

exemption from such tax granted it in Section 14 of its Charter,

R.A 6958, has been withdrawn.Since the last paragraph of

Section 234 unequivocally withdrew, upon the effectivity of the LGC,

exemptions from payment of real property taxes granted to natural

or juridical persons, including government-owned or controlled

corporations, except as provided in the said section, and the

petitioner is, undoubtedly, a government-owned corporation, it

necessarily follows that its exemption from such tax granted it in

Section 14 of its Charter, R.A. No. 6958, has been withdrawn. Any

claim to the contrary can only be justified if the petitioner can seek

refuge under any of the exceptions provided in Section 234, but not

under Section 133, as it now asserts, since, as shown above, the

said section is qualified by Sections 232 and 234.

LOCAL AND REAL PROPERTY TAXATION DOCTRINES

Same; Words and Phrases; The terms Republic of the

Philippines and National Government are not

interchangeablethe former is broader and synonymous with

Government of the Republic of the Philippines while the latter

refers to the entire machinery of the central government, as

distinguished from the different forms of local governments."The

terms Republic of the Philippines and National Government are

not interchangeable. The former is broader and synonymous with

Government of the Republic of the Philippines which the

Administrative Code of 1987 defines as the corporate

governmental entity through which the functions of government are

exercised throughout the Philippines, including, save as the

contrary appears from the context, the various arms through which

political authority is made effective in the Philippines, whether

pertaining to the autonomous regions, the provincial, city, municipal

or barangay subdivisions or other forms of local government.

These autonomous regions, provincial, city, municipal or barangay

subdivisions are the political subdivisions. On the other hand,

National Government refers to the entire machinery of the

central government, as distinguished from the different forms of

local governments. The National Government then is composed of

the three great departments: the executive, the legislative and the

judicial.

Same; Same; Agency and Instrumentality, Explained.An

agency of the Government refers to any of the various units of

the Government, including a department, bureau, office,

instrumentality, or government-owned or controlled corporation,

or a local government or a distinct unit therein; while an

instrumentality refers to any agency of the National Government,

not integrated within the department framework, vested with

special functions or jurisdiction by law, endowed with some if not all

corporate powers, administering special funds, and enjoying

operational autonomy, usually through a charter. This term includes

regulatory agencies, chartered institutions and government-owned

and controlled corporations.

Same; Local Government Units; Local Autonomy; The power to

tax is the most effective instrument to raise needed revenues

to finance and support myriad activities of local government

units for the delivery of basic services essential to the

promotion of the general welfare and the enhancement of

peace, progress, and prosperity of the people.The justification

for this restricted exemption in Section 234(a) seems obvious: to

limit further tax exemption privileges, especially in light of the

general provision on withdrawal of tax exemption privileges in

Section 193 and the special provision on withdrawal of exemption

from payment of real property taxes in the last paragraph of

Section 234. These policy considerations are consistent with the

State policy to ensure autonomy to local governments and the

objective of the LGC that they enjoy genuine and meaningful local

11/01/2014

autonomy to enable them to attain their fullest development as

selfreliant communities and make them effective partners in the

attainment of national goals. The power to tax is the most effective

instrument to raise needed revenues to finance and support myriad

activities of local government units for the delivery of basic

services essential to the promotion of the general welfare and the

enhancement of peace, progress, and prosperity of the people. It

may also be relevant to recall that the original reasons for the

withdrawal of tax exemption privileges granted to governmentowned and controlled corporations and all other units of

government were that such privilege resulted in serious tax base

erosion and distortions in the tax treatment of similarly situated

enterprises, and there was a need for these entities to share in the

requirements of development, fiscal or otherwise, by paying the

taxes and other charges due from them.

Same; Mactan Cebu International Airport Authority cannot

claim that it was never a taxable person under its Charter

it was only exempted from the payment of real property taxes.

Moreover, the petitioner cannot claim that it was never a taxable

person under its Charter. It was only exempted from the payment

of real property taxes. The grant of the privilege only in respect of

this tax is conclusive proof of the legislative intent to make it a

taxable person subject to all taxes, except real property tax.

Same; Local Government Units; Local Government Code;

Reliance on Basco vs. Philippine Amusement and Gaming

Corporation, 197 SCRA 52 (1991), is unavailing since it was

decided before the effectivity of the LGC.Accordingly, the

position taken by the petitioner is untenable. Reliance on Basco vs.

Philippine Amusement and Gaming Corporation is unavailing since it

was decided before the effectivity of the LGC. Besides, nothing can

prevent Congress from decreeing that even instrumentalities or

agencies of the Government performing governmental functions

may be subject to tax. Where it is done precisely to fulfill a

constitutional mandate and national policy, no one can doubt its

wisdom. [Mactan Cebu International Airport Authority vs.

Marcos, 261 SCRA 667(1996)]

Taxation; Municipal Corporations; Local Governments; Local

governments do not have the inherent power to tax except to

the extent that such power might be delegated to them either

by the basic law or by statute.Prefatorily, it might be well to

recall that local governments do not have the inherent power to tax

except to the extent that such power might be delegated to them

either by the basic law or by statute. Presently, under Article X of

the 1987 Constitution, a general delegation of that power has been

given in favor of local government units.

Same; Same; Same; Under the regime of the 1935 Constitution

local government units derived their tax powers under a

limited statutory authority.Under the regime of the 1935

LOCAL AND REAL PROPERTY TAXATION DOCTRINES

Constitution no similar delegation of tax powers was provided, and

local government units instead derived their tax powers under a

limited statutory authority. Whereas, then, the delegation of tax

powers granted at that time by statute to local governments was

confined and defined (outside of which the power was deemed

withheld), the present constitutional rule (starting with the 1973

Constitution), however, would broadly confer such tax powers

subject only to specific exceptions that the law might prescribe.

Same; Same; Same; Limitations on the Exercise of Taxing

Power by Local Government Units; Under the now prevailing

Constitution, where there is neither a grant nor a prohibition

by statute, the tax power must be deemed to exist although

Congress may provide statutory limitations and guidelines.

Under the now prevailing Constitution, where there is neither a

grant nor a prohibition by statute, the tax power must be deemed to

exist although Congress may provide statutory limitations and

guidelines. The basic rationale for the current rule is to safeguard

the viability and self-sufficiency of local government units by

directly granting them general and broad tax powers. Nevertheless,

the fundamental law did not intend the delegation to be absolute and

unconditional; the constitutional objective obviously is to ensure

that, while the local government units are being strengthened and

made more autonomous, the legislature must still see to it that (a)

the taxpayer will not be over-burdened or saddled with multiple and

unreasonable impositions; (b) each local government unit will have

its fair share of available resources; (c) the resources of the

national government will not be unduly disturbed; and (d) local

taxation will be fair, uniform, and just.

Same; Same; Same; Indicative of the legislative intent to carry

out the Constitutional mandate of vesting broad tax powers to

local government units, the Local Government Code has

effectively withdrawn tax exemptions or incentives

theretofore enjoyed by certain entities.Indicative of the

legislative intent to carry out the Constitutional mandate of vesting

broad tax powers to local government units, the Local Government

Code has effectively withdrawn, under Section 193 thereof, tax

exemptions or incentives theretofore enjoyed by certain entities.

This law states: Section 193. Withdrawal of Tax Exemption

Privileges.Unless otherwise provided in this Code, tax exemptions

or incentives granted to, or presently enjoyed by all persons,

whether natural or juridical, including government-owned or

controlled corporations, except local water districts, cooperatives

duly registered under R.A. No. 6938, non-stock and non-profit

hospitals and educational institutions, are hereby withdrawn upon

the effectivity of this Code. (Italics supplied for emphasis)

Same; Same; Same; The Supreme Court has viewed its

previous rulings as laying stress more on the legislative intent

of the amendatory lawwhether the tax exemption privilege is

to be withdrawn or notrather than on whether the law can

11/01/2014

withdraw, without violating the Constitution, the tax exemption

or not.In the recent case of the City Government of San Pablo,

etc., et al. vs. Hon. Bienvenido V. Reyes, et al., the Court has held

that the phrase in lieu of all taxes have to give way to the

peremptory language of the Local Government Code specifically

providing for the withdrawal of such exemptions, privileges, and

that upon the effectivity of the Local Government Code all

exemptions except only as provided therein can no longer be

invoked by MERALCO to disclaim liability for the local tax. In fine,

the Court has viewed its previous rulings as laying stress more on

the legislative intent of the amendatory lawwhether the tax

exemption privilege is to be withdrawn or notrather than on

whether the law can withdraw, without violating the Constitution,

the tax exemption or not.

Same; Same; Same; Non-Impairment Clause; Contractual tax

exemptions, in the real sense of the term and where the nonimpairment clause of the Constitution can rightly be invoked,

are those agreed to by the taxing authority in contracts, such

as those contained in government bonds or debentures,

lawfully entered into by them under enabling laws in which the

government, acting in its private capacity, sheds its cloak of

authority and waives its governmental immunity, which

contractual tax exemptions, however, are not to be confused

with tax exemptions granted under franchises.While the Court

has not too infrequently, referred to tax exemptions contained in

special franchises as being in the nature of contracts and a part of

the inducement for carrying on the franchise, these exemptions,

nevertheless, are far from being strictly contractual in nature.

Contractual tax exemptions, in the real sense of the term and where

the non-impairment clause of the Constitution can rightly be

invoked, are those agreed to by the taxing authority in contracts,

such as those contained in government bonds or debentures,

lawfully entered into by them under enabling laws in which the

government, acting in its private capacity, sheds its cloak of

authority and waives its governmental immunity. Truly, tax

exemptions of this kind may not be revoked without impairing the

obligations of contracts. These contractual tax exemptions,

however, are not to be confused with tax exemptions granted under

franchises. A franchise partakes the nature of a grant which is

beyond the purview of the non-impairment clause of the

Constitution. Indeed, Article XII, Section 11, of the 1987 Constitution,

like its precursor provisions in the 1935 and the 1973 Constitutions,

is explicit that no franchise for the operation of a public utility shall

be granted except under the condition that such privilege shall be

subject to amendment, alteration or repeal by Congress as and

when the common good so requires. [Manila Electric Company vs.

Province of Laguna, 306 SCRA 750(1999)]

Constitutional Law; Local Governments; Local Government

Code; Taxation; Words and Phrases; Franchise, defined.

LOCAL AND REAL PROPERTY TAXATION DOCTRINES

11/01/2014

Section 131 (m) of the LGC defines a franchise as a right or

privilege, affected with public interest which is conferred upon

private persons or corporations, under such terms and conditions

as the government and its political subdivisions may impose in the

interest of the public welfare, security and safety.

on the National Government, its agencies and instrumentalities, and

local government units. (emphasis supplied)

Same; Same; Same; Same; Same; Business, defined.On the

general or primary franchise, or to a special or secondary

franchise. The former relates to the right to exist as a corporation,

by virtue of duly approved articles of incorporation, or a charter

pursuant to a special law creating the corporation. The right under

a primary or general franchise is vested in the individuals who

compose the corporation and not in the corporation itself. On the

other hand, the latter refers to the right or privileges conferred

upon an existing corporation such as the right to use the streets of

a municipality to lay pipes of tracks, erect poles or string wires. The

rights under a secondary or special franchise are vested in the

corporation and may ordinarily be conveyed or mortgaged under a

general power granted to a corporation to dispose of its property,

except such special or secondary franchises as are charged with a

public use.

other hand, section 131 (d) of the LGC defines business as trade

or commercial activity regularly engaged in as means of livelihood

or with a view to profit. Petitioner claims that it is not engaged in

an activity for profit, in as much as its charter specifically provides

that it is a non-profit organization.

Same; Same; Same; Same; The theory behind the exercise of

the power to tax emanates from necessity.Taxes are the

lifeblood of the government, for without taxes, the government can

neither exist nor endure. A principal attribute of sovereignty, the

exercise of taxing power derives its source from the very existence

of the state whose social contract with its citizens obliges it to

promote public interest and common good. The theory behind the

exercise of the power to tax emanates from necessity; without

taxes, government cannot fulfill its mandate of promoting the

general welfare and well-being of the people.

Same; Same; Same; Same; The power to tax is no longer vested

exclusively on Congress.In recent years, the increasing social

challenges of the times expanded the scope of state activity, and

taxation has become a tool to realize social justice and the

equitable distribution of wealth, economic progress and the

protection of local industries as well as public welfare and similar

objectives. Taxation assumes even greater significance with the

ratification of the 1987 Constitution. Thenceforth, the power to tax

is no longer vested exclusively on Congress; local legislative bodies

are now given direct authority to levy taxes, fees and other charges

pursuant to Article X, section 5 of the 1987 Constitution.

Same; Same; Same; Same; One of the most significant

provisions of the Local Government Code is the removal of the

blanket exclusion of instrumentalities and agencies of the

national government from the coverage of local taxation.One

of the most significant provisions of the LGC is the removal of the

blanket exclusion of instrumentalities and agencies of the national

government from the coverage of local taxation. Although as a

general rule, LGUs cannot impose taxes, fees or charges of any kind

on the National Government, its agencies and instrumentalities, this

rule now admits an exception, i.e., when specific provisions of the

LGC authorize the LGUs to impose taxes, fees or charges on the

aforementioned entities, viz.: Section 133. Common Limitations on

the Taxing Powers of the Local Government Units.Unless

otherwise provided herein, the exercise of the taxing powers of

provinces, cities, municipalities, and barangays shall not extend to

the levy of the following: x x x (o) Taxes, fees, or charges of any kind

Same; Same; Same; Same; Franchises; A franchise may refer

to a general or primary franchise, or to a special or secondary

franchise.In its specific sense, a franchise may refer to a

Same; Same; Same; Same; Words and Phrases; Franchise Tax;

Definition; Requisites.As commonly used, a franchise tax is a

tax on the privilege of transacting business in the state and

exercising corporate franchises granted by the state. It is not

levied on the corporation simply for existing as a corporation, upon

its property or its income, but on its exercise of the rights or

privileges granted to it by the government. Hence, a corporation

need not pay franchise tax from the time it ceased to do business

and exercise its franchise. It is within this context that the phrase

tax on businesses enjoying a franchise in section 137 of the LGC

should be interpreted and understood. Verily, to determine whether

the petitioner is covered by the franchise tax in question, the

following requisites should concur: (1) that petitioner has a

franchise in the sense of a secondary or special franchise; and

(2) that it is exercising its rights or privileges under this franchise

within the territory of the respondent city government.

Same; Same; Same; Same; The power to tax is the most

effective instrument to raise needed revenues to finance and

support myriad activities of the local government units.

Doubtless, the power to tax is the most effective instrument to

raise needed revenues to finance and support myriad activities of

the local government units for the delivery of basic services

essential to the promotion of the general welfare and the

enhancement of peace, progress, and prosperity of the people. As

this Court observed in the Mactan case, the original reasons for

the withdrawal of tax exemption privileges granted to governmentowned or controlled corporations and all other units of government

were that such privilege resulted in serious tax base erosion and

distortions in the tax treatment of similarly situated enterprises.

With the added burden of devolution, it is even more imperative for

LOCAL AND REAL PROPERTY TAXATION DOCTRINES

government entities to share in the requirements of development,

fiscal or otherwise, by paying taxes or other charges due from

them. [National Power Corporation vs. City of Cabanatuan, 401

SCRA 259(2003)]

Taxation; Realty Tax; Franchises; Local Governments; While

Section 14 of Republic Act 3259 may be validly viewed as an

implied delegation of power to tax, the delegation under that

provision, as couched, is limited to impositions over properties

of the franchisee which are not actually, directly and

exclusively used in the pursuit of its franchise.The legislative

intent expressed in the phrase exclusive of this franchise cannot

be construed other than distinguishing between two (2) sets of

properties, be they real or personal, owned by the franchisee,

namely, (a) those actually, directly and exclusively used in its radio

or telecommunications business, and (b) those properties which

are not so used. It is worthy to note that the properties subject of

the present controversy are only those which are admittedly falling

under the first category. To the mind of the Court, Section 14 of Rep.

Act No. 3259 effectively works to grant or delegate to local

governments of Congress inherent power to tax the franchisees

properties belonging to the second group of properties indicated

above, that is, all properties which, exclusive of this franchise, are

not actually and directly used in the pursuit of its franchise. As may

be recalled, the taxing power of local governments under both the

1935 and the 1973 Constitutions solely depended upon an enabling

law. Absent such enabling law, local government units were without

authority to impose and collect taxes on real properties within their

respective territorial jurisdictions. While Section 14 of Rep. Act No.

3259 may be validly viewed as an implied delegation of power to

tax, the delegation under that provision, as couched, is limited to

impositions over properties of the franchisee which are not

actually, directly and exclusively used in the pursuit of its franchise.

Necessarily, other properties of Bayantel directly used in the

pursuit of its business are beyond the pale of the delegated taxing

power of local governments. In a very real sense, therefore, real

properties of Bayantel, save those exclusive of its franchise, are

subject to realty taxes. Ultimately, therefore, the inevitable result

was that all realties which are actually, directly and exclusively

used in the operation of its franchise are exempted from any

property tax. Bayantels franchise being national in character, the

exemption thus granted under Section 14 of Rep. Act No. 3259

applies to all its real or personal properties found anywhere within

the Philippine archipelago.

Same; Same; Same; Same; The realty tax exemption heretofore

enjoyed by Bayantel under its original franchise, but

subsequently withdrawn by force of Section 234 of the Local

Government Code, has been restored by Section 14 of Republic

Act No. 7633.With the LGCs taking effect on January 1, 1992,

Bayantels exemption from real estate taxes for properties of

11/01/2014

whatever kind located within the Metro Manila area was, by force of

Section 234 of the Code, expressly withdrawn. But, not long

thereafter, however, or on July 20, 1992, Congress passed Rep. Act

No. 7633 amending Bayantels original franchise. Worthy of note is

that Section 11 of Rep. Act No. 7633 is a virtual reenacment of the

tax provision, i.e., Section 14, of Bayantels original franchise under

Rep. Act No. 3259. Stated otherwise, Section 14 of Rep. Act No. 3259

which was deemed impliedly repealed by Section 234 of the LGC

was expressly revived under Section 14 of Rep. Act No. 7633. In

concrete terms, the realty tax exemption heretofore enjoyed by

Bayantel under its original franchise, but subsequently withdrawn

by force of Section 234 of the LGC, has been restored by Section 14

of Rep. Act No. 7633.

Same; Same; Same; Same; The power to tax is primarily vested

in the Congress; however, in our jurisdiction, it may be

exercised by local legislative bodies, no longer merely by

virtue of a valid delegation as before, but pursuant to direct

authority conferred by Section 5, Article X of the

Constitution.Bayantels posture is well-taken. While the system

of local government taxation has changed with the onset of the 1987

Constitution, the power of local government units to tax is still

limited. As we explained in Mactan Cebu International Airport

Authority: The power to tax is primarily vested in the Congress;

however, in our jurisdiction, it may be exercised by local legislative

bodies, no longer merely by virtue of a valid delegation as before,

but pursuant to direct authority conferred by Section 5, Article X of

the Constitution. Under the latter, the exercise of the power may be

subject to such guidelines and limitations as the Congress may

provide which, however, must be consistent with the basic policy of

local autonomy. (at p. 680; Emphasis supplied.)

Same; Same; Same; Same; The Supreme Court has upheld the

power of Congress to grant exemptions over the power of

local government units to impose taxes.In Philippine Long

Distance Telephone Company, Inc. (PLDT) vs. City of Davao, 363

SCRA 522 (2001), this Court has upheld the power of Congress to

grant exemptions over the power of local government units to

impose taxes. There, the Court wrote: Indeed, the grant of taxing

powers to local government units under the Constitution and the

LGC does not affect the power of Congress to grant exemptions to

certain persons, pursuant to a declared national policy. The legal

effect of the constitutional grant to local governments simply

means that in interpreting statutory provisions on municipal taxing

powers, doubts must be resolved in favor of municipal

corporations. [City Government of Quezon City vs. Bayan

Telecommunications, Inc., 484 SCRA 169(2006)]

Taxation; Local Government Code; Section 133 prescribes the

limitations on the capacity of local government units to

exercise their taxing powers otherwise granted to them under

the Local Government Code (LGC); Two kinds of taxes which

LOCAL AND REAL PROPERTY TAXATION DOCTRINES

cannot be imposed by local government units.Section 133

prescribes the limitations on the capacity of local government units

to exercise their taxing powers otherwise granted to them under

the LGC. Apparently, paragraph (h) of the Section mentions two

kinds of taxes which cannot be imposed by local government units,

namely: excise taxes on articles enumerated under the National

Internal Revenue Code [(NIRC)], as amended; and taxes, fees or

charges on petroleum products.

Same; Same; Excise Tax; The current definition of an excise tax

is that of a tax levied on a specific article rather than one upon

the performance, carrying on, or the exercise of an activity.

It is evident that Am Jur aside, the current definition of an excise

tax is that of a tax levied on a specific article, rather than one upon

the perfor-mance, carrying on, or the exercise of an activity. This

current definition was already in place when the LGC was enacted in

1991, and we can only presume that it was what the Congress had

intended as it specified that local government units could not

impose excise taxes on articles enumerated under the [NIRC].

This prohibition must pertain to the same kind of excise taxes as

imposed by the NIRC, and not those previously defined excise

taxes which were not integrated or denominated as such in our

present tax law.

Same; Same; Same; Starting in 1986, excise taxes in this

jurisdiction refer exclusively to specific or ad valorem taxes,

imposed under the National Internal Revenue Code (NIRC).It

is quite apparent, therefore, that our current body of taxation law

does not explicitly accommodate the traditional definition of excise

tax offered by Petron. In fact, absent any statutory adoption of the

traditional definition, it may be said that starting in 1986 excise

taxes in this jurisdiction refer exclusively to specific or ad valorem

taxes imposed under the NIRC. At the very least, it is this concept of

excise tax which we can reasonably assume that Congress had in

mind and actually adopted when it crafted the LGC. The palpable

absurdity that ensues should the alternative interpretation prevail

all but strengthens this position.

Same; Same; Same; Congress has the constitutional authority

to impose limitations on the power to tax of local government

units and Section 133 of the Local Government Code (LGC) is

one such limitation.Congress has the constitutional authority to

impose limitations on the power to tax of local government units,

and Section 133 of the LGC is one such limitation. Indeed, the

provision is the explicit statutory impediment to the enjoyment of

absolute taxing power by local government units, not to mention the

reality that such power is a delegated power. To cite one example,

under Section 133(g), local government units are disallowed from

levying business taxes on business enterprises certified to by the

Board of Investments as pioneer or non-pioneer for a period of six

(6) and (4) four years, respectively from the date of registration.

11/01/2014

Same; Same; Same; The prohibition with respect to petroleum

products extends not only to excise taxes thereon, but all

taxes, fees and charges.The language of Section 133(h) makes

plain that the prohibition with respect to petroleum products

extends not only to excise taxes thereon, but all taxes, fees and

charges. The earlier reference in paragraph (h) to excise taxes

comprehends a wider range of subjects of taxation: all articles

already covered by excise taxation under the NIRC, such as alcohol

products, tobacco products, mineral products, automobiles, and

such non-essential goods as jewelry, goods made of precious

metals, perfumes, and yachts and other vessels intended for

pleasure or sports. In contrast, the later reference to taxes, fees

and charges pertains only to one class of articles of the many

subjects of excise taxes, specifically, petroleum products. While

local government units are authorized to burden all such other

class of goods with taxes, fees and charges, excepting excise

taxes, a specific prohibition is imposed barring the levying of any

other type of taxes with respect to petroleum products.

Same; Same; Same; Even absent Article 232, local government

units cannot impose business taxes on petroleum products.

Assuming that the LGC does not, in fact, prohibit the imposition of

business taxes on petroleum products, we would agree that the IRR

could not impose such a prohibition. With our ruling that Section

133(h) does indeed prohibit the imposition of local business taxes on

petroleum products, however, the RTC declaration that Article 232

was invalid is, in turn, itself invalid. Even absent Article 232, local

government units cannot impose business taxes on petroleum

products. If anything, Article 232 merely reiterates what the LGC

itself already provides, with the additional explanation that such

prohibition was in line with existing national policy. [Petron

Corporation vs. Tiangco, 551 SCRA 484(2008)]

Local Governments; Municipal Corporations; Tax Ordinances;

An appeal of a tax ordinance or revenue measure should be

made to the Secretary of Justice within thirty (30) days from

effectivity of the ordinance and even during its pendency, the

effectivity of the assailed ordinance shall not be suspended.

The aforecited law requires that an appeal of a tax ordinance or

revenue measure should be made to the Secretary of Justice within

thirty (30) days from effectivity of the ordinance and even during

its pendency, the effectivity of the assailed ordinance shall not be

suspended. In the case at bar, Municipal Ordinance No. 28 took

effect in October 1996. Petitioner filed its appeal only in December

1997, more than a year after the effectivity of the ordinance in 1996.

Clearly, the Secretary of Justice correctly dismissed it for being

time-barred.

Same; Same; Same; Same; The timeframe fixed by law for

parties to avail of their legal remedies before competent

courts is not a mere technicality that can be easily brushed

asidethe periods stated in Section 187 of the Local

LOCAL AND REAL PROPERTY TAXATION DOCTRINES

11/01/2014

Government Code are mandatory.At this point, it is apropos to

who used to sell their goods along the sidewalk. [Hagonoy Market

state that the timeframe fixed by law for parties to avail of their

legal remedies before competent courts is not a mere

technicality that can be easily brushed aside. The periods stated in

Section 187 of the Local Government Code are mandatory.

Ordinance No. 28 is a revenue measure adopted by the municipality

of Hagonoy to fix and collect public market stall rentals. Being its

lifeblood, collection of revenues by the government is of paramount

importance. The funds for the operation of its agencies and

provision of basic services to its inhabitants are largely derived

from its revenues and collections. Thus, it is essential that the

validity of revenue measures is not left uncertain for a considerable

length of time. Hence, the law provided a time limit for an aggrieved

party to assail the legality of revenue measures and tax ordinances.

Vendor Association vs. Municipality of Hagonoy, Bulacan, 376

SCRA 376(2002)]

Local Governments; Ordinances; Public Hearings; Public

hearings are conducted by legislative bodies to allow

interested parties to ventilate their views on a proposed law

or ordinance, but these views are not binding on the legislative

bodiesparties who participate in public hearings to give their

opinions on a proposed ordinance should not expect that their views

would be patronized by their lawmakers.Petitioner cannot gripe

that there was practically no public hearing conducted as its

objections to the proposed measure were not considered by the

Sangguniang Bayan. To be sure, public hearings are conducted by

legislative bodies to allow interested parties to ventilate their views

on a proposed law or ordinance. These views, however, are not

binding on the legislative body and it is not compelled by law to

adopt the same. Sanggunian members are elected by the people to

make laws that will promote the general interest of their

constituents. They are mandated to use their discretion and best

judgment in serving the people. Parties who participate in public

hearings to give their opinions on a proposed ordinance should not

expect that their views would be patronized by their lawmakers.

Same; Same; Section 6c.04 of the 1993 Municipal Revenue

Code and Section 191 of the Local Government Code limiting the

percentage of increase that can be imposed apply to tax rates,

not rentals.Finally, even on the substantive points raised, the

petition must fail. Section 6c.04 of the 1993 Municipal Revenue Code

and Section 191 of the Local Government Code limiting the

percentage of increase that can be imposed apply to tax rates, not

rentals. Neither can it be said that the rates were not uniformly

imposed or that the public markets included in the Ordinance were

unreasonably determined or classified. To be sure, the Ordinance

covered the three (3) concrete public markets: the two-storey

Bagong Palengke, the burnt but reconstructed Lumang Palengke and

the more recent Lumang Palengke with wet market. However, the

Palengkeng Bagong Munisipyo or Gabaldon was excluded from the

increase in rentals as it is only a makeshift, dilapidated place, with

no doors or protection for security, intended for transient peddlers

Municipal law; Taxation; Licenses; Authority to impose licenses;

Kinds.Under the provisions of Section 1 of Commonwealth Act 472

and pertinent jurisprudence, a municipality is authorized to impose

three kinds of licenses: (1) license for regulation of useful

occupations or enterprises; (2) license for restriction or regulation

of non-usef ul occupations or enterprises; and (3) license for

revenue (Cf. Cu Unjieng v. Patstone, 42 Phil. 818). The first two

easily fall within the broad police power granted under the general

welfare clause (Sec, 2238, Rev. Adm. Code). The third class,

however, is for revenue purposes. It is not a license fee, properly

speaking, and yet it is generally so termed. It rests on the taxing

power. That taxing power must be expressly conferred by statute

upon the municipality (Sec. 2287, Rev. Adm. Code; Cu Unjieng v.

Patstone, supra; People v. Felisarta, L-15346, June 29, 1962, etc.).

Same; Concept of municipal license tax; Designation given does

not decide whether the imposition is a license tax or a license

fee; Determining factors.The use of the term "municipal license

tax" does not necessarily connote the idea that the tax is imposed

as a revenue measure in the guise of a license tax. For really, this

runs counter to the declared purpose to make money. Besides, the

term "license tax" has not acquired a fixed meaning. It is often

"used indiscriminately to designate impositions exacted for the

exercise of various privileges. In many instances, it refers to

"revenue-raising exactions on privileges or activities". On the other

hand, license fees are commonly called taxes. But legally speaking,

the latter are "'for the purpose of raising revenues", in contrast to

the f ormer which are imposed "in the exercise of the police power

for purposes of regulation". (Compaia General de Tabacos de

Filipinas v. City of Manila, L-16619, June 29, 1963.)

Same; Percentage taxation; Doctrine of preemption; When not

applicable.What can be said at most is that the national

government has preempted the f ield of percentage taxation.

Section 1 of C. A. 472, while granting municipalities power to levy

taxes, expressly removes from them the power to exact

"percentage taxes".

It is correct to say that preemption in the matter of taxation simply

refers to an instance where the national government elects to tax a

particular area, impliedly withholding from the local government the

delegated power to tax the same field. This doctrine primarily rests

upon the intention of Congress. Conversely, should Congress allow

municipal corporations to cover fields of taxation it already

occupies, then the doctrine of preemption will not apply.

In the case at bar, Section 4 (1) of C. A. 472 clearly and specifically

allows municipal councils to tax persons engaged in "the same

LOCAL AND REAL PROPERTY TAXATION DOCTRINES

businesses or occupation" on which "fixed internal revenue

privilege taxes" are "regularly imposed by the Government".

Same; Ordinance No. 1, Series of 1956, held valid; Case at bar.

In the case at bar, Ordinance No. 1 was approved by the municipality

of Victorias on September 22, 1956 by way of an amendment to two

municipal ordinances separately imposing license taxes on

operators of sugar centrals and sugar ref ineries. The changes

were: with respect to sugar centrals, by increasing the rates of

license taxes; and so to sugar refineries, by increasing the rates of

license taxes as well as the range of graduated schedule of annual

output capacity.

In the absence of sufficient proof that license taxes are

unreasonable, the presumption of validity subsists. A cash sur-plus

alone cannot stop a municipality from enacting a revenue ordinance

increasing license taxes in anticipation of municipal needs.

Discretion to determine the amount of revenue required for the

needs of the municipality is lodged with the municipal authorities.

Judicial intervention steps in only when there is a flagrant,

oppressive and excessive abuse of power by said municipal

authorities.

Said Ordinance No. 1, series of 1956, is not discriminatory. The

ordinance does not single out Victorias as the only object of the

ordinance. Said ordinance is made to apply to any sugar central or

sugar refinery which may happen to operate in the municipality. So

it is, that the fact that plaintiff is actually the sole operator of a

sugar central and a sugar refinery does not make the ordinance

discriminatory (Cf. also Shell Co. of P.I. v. Vao, 94 Phil. 389 and

Ormoc Sugar Co., Inc. v. Mun. Board of Ormoc City, L-24322, July 21,

1967)

We, accordingly, rule that Ordinance No. 1, series of 1956, of the

Municipality of Victorias, was promulgated not in the exercise of the

municipality's regulatory power but as a revenue measuretax on

occupation or business. The authority to impose such tax is backed

by the express grant of power in Section 1 of C.A. No. 472.

Same; Double taxation; Description; Existence; Definition;

Where no double taxation exists; Case at bar.Double taxation

has been otherwise described as "direct duplicate taxation". For

double taxation to exist, the same property must be taxed twice,

when it should be taxed but once. Double taxation has been also def

ined as taxing the same person twice by the same jurisdiction for

the same thing (Cf. Manila Motor Co., Inc. v. Ciudad de Manila, 72

Phil. 336). In the case at bar, plaintiff's argument on double taxation

does not inspire assent. First. The two taxes cover two different

objects. Section 1 of the ordinance taxes a person operating sugar

centrals or engaged in the manufacture of centrifugal sugar. While

under Section 2, those taxed are the operators of sugar refinery

mills. One occupation or business is different from the other.

Second. The disputed taxes are imposed on occupation or business.

11/01/2014

Both taxes are not on sugar. The amount thereof depends on the

annual output capacity of the mills concerned, regardless of the

actual sugar milled. Plaintiff's argument perhaps could make out a

point if the object of taxation here were the sugar it produces, not

the business of producing it. [Victorias Milling Co., Inc. vs. Mun. of

Victorias, Negros Occidental, 25 SCRA 192(1968)]

A close scrutiny of the ordinances complained of reveals that the

fees therein imposed are not by reason of the services performed

by the Mayor or the Veterinary Officer, but as an imposition on

every head of the specified animals to be' transported. The fact that

the ordinances in question make no reference to the purpose for

which they were enacted, and that such purpose was to preserve

the public health or welfare of the residents and people of the City

of Tacloban, is a clear indication that leads this Court to believe that

the fees exacted were not as a regulatory measure in the

exercise of its police power, but for the purpose of raising

revenue under the guise of license or inspection fees. An act

or ordinance imposing a license or license tax under the police

power as a means of regulation is valid only when it is within

the limits of such power and is intended for regulation;

otherwise, it is invalid as where the license or tax is

unnecessarily imposed on an occupation or business not

inherently subject to police regulation (Southwest Utility Ice Co.

vs. Liebmann, 52 F. 2d 349), for an act or ordinance imposing a

license or license tax for revenue purposes, under the guise of a

police or regulatory measure, is invalid (Southern Fruit Co. vs.

Porter, 199 S.E. 537). [AGUSTIN PANALIGAN, CASIMIRO SEBOLINO,

EPIFANIA UDTUJAN, VALENTIN CAMPOSANO, ANGELES

GUANTERO, EsTEBAN JUNTILLA, ClRIACA DE GALAGAR, MARCOS

SAMSON, RAMON HERNANDEZ OR ARANDES, EPIFANIO PABILONA

and PEDRO RODRIGUEZ, petitioners and appellees, vs. THE CITY

OF TACLOBAN and THE CITY TREASURER OF THE CITY OF

TACLOBAN, respondents and appellants., 102 Phil. 1162(1957)]

Taxation; Section 133(e) of RA No. 7160 prohibit the imposition,

in the guise of wharfage, of feesas well as all other taxes or

charges in any form whatsoever.By express language of

Sections 153 and 155 of RA No. 7160, local government units,

through their Sanggunian, may prescribe the terms and conditions

for the imposition of toll fees or charges for the use of any public

road, pier or wharf funded and constructed by them. A service fee

imposed on vehicles using municipal roads leading to the wharf is

thus valid. However, Section 133(e) of RA No. 7160 prohibits the

imposition, in the guise of wharfage, of feesas well as all other

taxes or charges in any form whatsoeveron goods or

merchandise. It is therefore irrelevant if the fees imposed are

actually for police surveillance on the goods, because any other

form of imposition on goods passing through the territorial

jurisdiction of the municipality is clearly prohibited by Section

133(e).

LOCAL AND REAL PROPERTY TAXATION DOCTRINES

Same; A wharfage does not lose its basic character by being

labeled as a service fee for police surveillance on all

goods.Under Section 131 (y) of RA No. 7160, wharfage is defined

as a fee assessed against the cargo of a vessel engaged in foreign

or domestic trade based on quantity, weight, or measure received

and/or discharged by vessel. It is apparent that a wharfage does

not lose its basic character by being labeled as a service fee for

police surveillance on all goods.

Same; Unjust Enrichment; Two conditions for unjust

enrichment to be deemed present; There is no unjust

enrichment where the one receiving the benefit has a legal

right or entitlement thereto, or when there is no causal

relation between ones enrichment and the others

impoverishment.Unpersuasive is the contention of respondent

that petitioner would unjustly be enriched at the formers expense.

Though the rules thereon apply equally well to the government, for

unjust enrichment to be deemed present, two conditions must

generally concur: (a) a person is unjustly benefited, and (b) such

benefit is derived at anothers expense or damage. In the instant

case, the benefits from the use of the municipal roads and the

wharf were not unjustly derived by petitioner. Those benefits

resulted from the infrastructure that the municipality was

mandated by law to provide. There is no unjust enrichment where

the one receiving the benefit has a legal right or entitlement

thereto, or when there is no causal relation between ones

enrichment and the others impoverishment. [Palma Development

Corporation vs. Municipality of Malangas, Zamboanga del Sur,

413 SCRA 572(2003)]

Taxation, Municipal Corporations; The City of Cebu may not

impose an additional amusement tax on top of that already

imposed as would make the Citys amusement tax higher than

that of the Province of Cebu.Under Section 13 of the Local Tax

Code, the province is authorized to impose an amusement tax of

20% or 30% depending on the amount paid for admission. But

under secs. 57 and 65 (G) of its Tax Ordinance No. 1 now in question,

petitioner Cebu City is authorized to impose an additional P0.05

amusement tax (on top of the amusement tax the city is admittedly

authorized to impose under section 23 of the Local Tax Code). In

effect, Cebu City will have a higher rate of amusement tax than

Cebu province. This disparity in rates is precisely what is

proscribed by the second paragraph of section 23 earlier quoted.

The said section speaks of uniform for the city and the province or

municipality. Hence, what is required is uniformity of amusement

taxes between the province and the city; not uniformity of the rates

on the same subject.

Same: Same: Multiple permit fees for engaging in the same

business is unreasonable and oppressive.As correctly

observed by respondent Court, the law (Section 36) contemplates a

single fee for the issuance of a permit to engage in any business or

11/01/2014

occupation. But Sec. 74 (Q) of Tax Ordinance No. 1 imposes another

permit fee on foods and drugs establishments. As a result, the

taxpayer will have to pay another permit fee for conducting the

same business in the same city. Such multiple imposition of permit

fees is unreasonable and oppressive and is definitely not sanctioned

by the Local Tax Code.

Same; Same; The Court finds the sheriffs storage fees

imposed in Cebu Citys tax ordinance as excessive and

confiscatory.As illustrated by respondent court in its assailed

decision, quoting the observation of the trial court, a typewriter

with a fair market value of P3,000.00 will have to pay a sheriffs

storage fee of P5.00 a day. Thus, it would take only 600 days, or

less than two years, for the typewriter to completely eat up its

value on account of storage fees. Being excessive and confiscatory,

the suspension of the imposition of storage fees by the lower court

was correct.

Same; Same: Fish is an agricultural product and an inspection

fee is not allowed to be imposed thereon under the Local Tax

Code, whether in its original form or not.The aforequoted

provision prohibits a local government from imposing an inspection

fee on agricultural products and fish is an agricultural product.

Contrary to the claim of petitioners, under Section 102 of City

Ordinance No. 1 a fisherman selling his fish within the city has to pay

the inspection fee of P0.03 for every kilo of fish sold. Furthermore,

the imposition of the tax will definitely restrict the free flow of fresh

fish to Cebu City because the price of fish will have to increase.

Same; Same; A local government cannot impose a specific tax

on a product, like beer, which is already subject to a national

specific tax as per P.D. 426.This power to tax articles subject

to specific tax which was expressly granted to cities by the original

provisions of section 24, was deleted in the amendment. The said

section 24, as it now reads, merely grants the city the power to

levy any tax, fee or other imposition not specifically enumerated or

otherwise provided for in the Local Tax Code. The amendment

evinces the intent of the lawmaker to remove such taxing authority

(on articles already subject to the national specific tax) from the

cities like Cebu City. [City of Cebu vs. Urot, 144 SCRA 710(1986)]

Taxation; Municipal Corporations; Local Government Units; A

province has no authority to impose taxes on stones, sand,

gravel, earth and other quarry resources extracted from

private lands.In any case, the remaining issues raised by

petitioner are likewise devoid of merit, a province having no

authority to impose taxes on stones, sand, gravel, earth and other

quarry resources extracted from private lands.

Same; Same; Same; A province may not levy excise taxes on

articles already taxed by the National Internal Revenue Code.

The Court of Appeals erred in ruling that a province can impose only

the taxes specifically mentioned under the Local Government Code.

10

LOCAL AND REAL PROPERTY TAXATION DOCTRINES

As correctly pointed out by petitioners, Section 186 allows a

province to levy taxes other than those specifically enumerated

under the Code, subject to the conditions specified therein. This

finding, nevertheless, affords cold comfort to petitioners as they

are still prohibited from imposing taxes on stones, sand, gravel,

earth and other quarry resources extracted from private lands. The

tax imposed by the Province of Bulacan is an excise tax, being a tax

upon the perfor-mance, carrying on, or exercise of an activity.

Same; Same; Same; A province may not ordinarily impose

taxes on stones, sand, gravel, earth and other quarry

resources, as the same are already taxed under the National

Internal Revenue Code.It is clearly apparent from the above

provision that the National Internal Revenue Code levies a tax on all

quarry resources, regardless of origin, whether extracted from

public or private land. Thus, a province may not ordinarily impose

taxes on stones, sand, gravel, earth and other quarry resources, as

the same are already taxed under the National Internal Revenue

Code. The province can, however, impose a tax on stones, sand,

gravel, earth and other quarry resources extracted from public

land because it is expressly empowered to do so under the Local

Government Code. As to stones, sand, gravel, earth and other

quarry resources extracted from private land, however, it may not

do so, because of the limitation provided by Section 133 of the Code

in relation to Section 151 of the National Internal Revenue Code.

Same; Same; Same; Natural Resources; Regalian Doctrine; A

province may not invoke the Regalian doctrine to extend the

coverage of its ordinance to quarry resources extracted from

private lands, for taxes, being burdens, are not to be

presumed beyond what the applicable statute expressly and

clearly declares, tax statutes being construed strictissimi

juris against the government.Section 21 of Provincial Ordinance

No. 3 is practically only a reproduction of Section 138 of the Local

Government Code. A cursory reading of both would show that both

refer to ordinary sand, stone, gravel, earth and other quarry

resources extracted from public lands. Even if we disregard the

limitation set by Section 133 of the Local Government Code,

petitioners may not impose taxes on stones, sand, gravel, earth and

other quarry resources extracted from private lands on the basis

of Section 21 of Provincial Ordinance No. 3 as the latter clearly

applies only to quarry resources extracted from public lands.

Petitioners may not invoke the Regalian doctrine to extend the

coverage of their ordinance to quarry resources extracted from

private lands, for taxes, being burdens, are not to be presumed

beyond what the applicable statute expressly and clearly declares,

tax statutes being construed strictissimi juris against the

government. [Province of Bulacan vs. Court of Appeals, 299

SCRA 442(1998)]

Taxation; Municipal Corporations; Declaratory Relief; In an

action for declaratory relief assailing the validity of a

11/01/2014

municipal tax ordinance, the court, in deciding that the

ordinance is void, is authorized to require a refund of taxes

paid thereunder without necessity of converting the

proceeding into an ordinary action there having been no

alleged violation of the ordinance yet.Under Sec. 6 of Rule 64,

the action for declaratory relief may be converted into an ordinary

action and the parties allowed to file such pleadings as may be

necessary or proper, if before the final termination of the case a

breach or violation of an . . . ordinance, should take place. In the

present case, no breach or violation of the ordinance occurred. The

petitioner decided to pay under protest the fees imposed by the

ordinance. Such payment did not affect the case; the declaratory

relief action was still proper because the applicability of the

ordinance to future transactions still remained to be resolved,

although the matter could also be threshed out in an ordinary suit

for the recovery of taxes paid (Shell Co. of the Philippines, Ltd. vs.

Municipality of Sipocot, L-12680, March 20, 1959). In its petition for

declaratory relief, petitioner-appellee alleged that by reason of the

enforcement of the municipal ordinance by respondents it was

forced to pay under protest the fees imposed pursuant to the said

ordinance, and accordingly, one of the reliefs prayed for by the

petitioner was that the respondents be ordered to refund all the

amounts it paid to respondent Municipal Treasurer during the

pendency of the case. The inclusion of said allegation and prayer in

the petitioner was not objected to by the respondents in their

answer. During the trial, evidence of the payments made by the

petitioner was introduced. Respondents were thus fully aware of

the petitioners claim for refund and of what would happen if the

ordinance were to be declared invalid by the court.

Same; Same; A fixed tax denominated as a police inspection

fee of P.30 per sack of cassava starch shipped out of the

municipality is void where it is not for a public purpose, just

and uniform because the police do nothing but count the

number of cassava sacks shipped out.However, the tax

imposed under the ordinance can be stricken down on another

ground. According to Section 2 of the abovementioned Act, the tax

levied must be for public purposes, just and uniform (Italics

supplied.) As correctly held by the trial court, the so-called police

inspection fee levied by the ordinance is unjust and

unreasonable.

Same; Same; Same.Said the court a quo: x x x It has been

proven that the only service rendered by the Municipality of

Malabang, by way of inspection, is for the policeman to verify from

the driver of the trucks of the petitioner passing by at the police

checkpoint the number of bags loaded per trip which are to be

shipped out of the municipality based on the trip tickets for the

purpose of computing the total amount of tax to be collect (sic) and

for no other purpose. The pretention of respondents that the police,

aside from counting the number of bags shipped out, is also

11

LOCAL AND REAL PROPERTY TAXATION DOCTRINES

inspecting the cassava flour starch contained in the bags to find out

if the said cassava flour starch is fit for human consumption could

not be given credence by the Court because, aside from the fact

that said purpose is not so stated in the ordinance in question, the

policemen of said municipality are not competent to determine if

the cassava flour starch are fit for human consumption. The further

pretention of respondents that the trucks of the petitioner hauling

the bags of cassava flour starch from the mill to the bodega at the

beach of Malabang are escorted by a policeman from the police

checkpoint to the beach for the purpose of protecting the truck and

its cargoes from molestation by undesirable elements could not

also be given credence by the Court because it has been shown,

beyond doubt, that the petitioner has not asked for the said police

protection because there has been no occasion where its trucks

have been molested, even for once, by bad elements from the police

checkpoint to the bodega at the beach, it is solely for the purpose of

verifying the correct number of bags of cassava flour starch loaded

on the trucks of the petitioner as stated in the trip tickets, when

unloaded at its bodega at the beach. The imposition, therefore, of a

police inspection fee of P. 30 per bag, imposed by said ordinance is

unjust and unreasonable. [Matalin Coconut Co., Inc. vs. Municipal

Council of Malabang, Lanao del Sur, 143 SCRA 404(1986)]

Taxation; The power to tax is an attribute of sovereignty, and

as such, inheres in the State. Such, however, is not true for

provinces, cities, municipalities and barangays as they are not

the sovereign; rather, they are mere territorial and political

subdivisions of the Republic of the Philippines.The power to

tax is an attribute of sovereignty, and as such, inheres in the

State. Such, however, is not true for provinces, cities, municipalities

and barangays as they are not the sovereign; rather, they are mere

territorial and political subdivisions of the Republic of the

Philippines. The rule governing the taxing power of provinces,

cities, municipalities and barangays is summarized in Icard v. City

Council of Baguio: It is settled that a municipal corporation unlike a

sovereign state is clothed with no inherent power of taxation. The

charter or statute must plainly show an intent to confer that power

or the municipality, cannot assume it. And the power when granted

is to be construed in strictissimi juris. Any doubt or ambiguity

arising out of the term used in granting that power must be

resolved against the municipality. Inferences, implications,

deductionsall thesehave no place in the interpretation of the

taxing power of a municipal corporation.

Same; The power of a province to tax is limited to the extent

that such power is delegated to it either by the Constitution or

by statute.The power of a province to tax is limited to the extent

that such power is delegated to it either by the Constitution or by

statute. Section 5, Article X of the 1987 Constitution is clear on this

point: Section 5. Each local government unit shall have the power to

create its own sources of revenues and to levy taxes, fees and

11/01/2014

charges subject to such guidelines and limitations as the Congress

may provide, consistent with the basic policy of local autonomy.

Such taxes, fees, and charges shall accrue exclusively to the local

governments.

Same; Constitutional Law; Per Section 5, Article X of the 1987

Constitution, the power to tax is no longer vested exclusively

on Congress; local legislative bodies are now given direct

authority to levy taxes, fees and other charges.Per Section

5, Article X of the 1987 Constitution, the power to tax is no longer

vested exclusively on Congress; local legislative bodies are now

given direct authority to levy taxes, fees and other charges.

Nevertheless, such authority is subject to such guidelines and

limitations as the Congress may provide. In conformity with

Section 3, Article X of the 1987 Constitution, Congress enacted

Republic Act No. 7160, otherwise known as the Local Government

Code of 1991. Book II of the LGC governs local taxation and fiscal

matters. Relevant provisions of Book II of the LGC establish the

parameters of the taxing powers of LGUS found below. First, Section

130 provides for the following fundamental principles governing the

taxing powers of LGUs: 1. Taxation shall be uniform in each LGU. 2.

Taxes, fees, charges and other impositions shall: a. be equitable and

based as far as practicable on the taxpayers ability to pay; b. be

levied and collected only for public purposes; c. not be unjust,

excessive, oppressive, or confiscatory; d. not be contrary to law,

public policy, national economic policy, or in the restraint of trade.

3. The collection of local taxes, fees, charges and other impositions

shall in no case be let to any private person. 4. The revenue

collected pursuant to the provisions of the LGC shall inure solely to

the benefit of, and be subject to the disposition by, the LGU levying

the tax, fee, charge or other imposition unless otherwise

specifically provided by the LGC. 5. Each LGU shall, as far as

practicable, evolve a progressive system of taxation.

Same; Percentage Tax; National Internal Revenue Code (R.A.