Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Lambert, Y - Religion in Modernity As A Axial Age

Transféré par

vffinderTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Lambert, Y - Religion in Modernity As A Axial Age

Transféré par

vffinderDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Sociology of Religion l 999, 60:3 303433

Religion in Modernity as a New Axial Age:

Secularization or New Fieligious Forms?

Yves Lambert*

Grmtpede$ociol-ogieiies Religions ettiela more

CNRS-EPHE_ Paris

This article proposes o general model of analysis of the relotiorts ltetween religion and modcniity,

it-liere modernity is conceived as o new axial age. Murlemiry appears to have four principal types of

religious effects: decline, odofrtotion and reintertnetotion, conser-vao've reaction, and innovation. It

fnocluces secularization as well as new rcligfotts fomzs, in particular: worlillistess, deltieftifchitotio of

the ltumon and the divine, selspirituolity, poroscientificitjr, plurolisrn, and rturlzilitj. Two thresltolds

of secularitotiort are distinguished: ll U autoaomization in relation to o religious authority and (Ii

obontlonmenr of any religious symbol. J conclude that the first rlireslioltl has largely been crossed, but

not the second one. except in some domains lscience, eooriomicsl or for onlgr o minority of the

population. This is because of the adaptation of the great religions to I'll-Ot.'ll'I"'l'llltj|', o_ffundarnemalist

reactions, and of the spread ofnew religious forms.

so

ll

|.ucu_ipage-oru

L|'\I

I'll

r_1

o

E'r_1

1:|

E

tn

no

U

'--.

l

Instead of approaching the question elf secularization directly, l will begin

with a general model of analysis of the relations between religion and modernity.

This model is based on a comparative analvsis of oral religions, religions of

antiquity, religions of salvation, and the transforrnations linlcecl to modernity. ln

itself, seculo rizarion is not the object of this work, but if we proceed correctlv, it

should allow us to evaluate the scope of secularization without entering into the

debates and emotions to which this thesis has given rise in the past thirty years.

A large portion of the article will thus he devoted to an analysis of the relation

between religion and tnodernitv. It characterizes modernity as a new axial

period, reviews the global analyses of the religious consequences of modernity,

presents a model of analvsis and several religious forms typical of mo-demitv, and

provides empirical illustrations. We shall then examine the conclusions which

can be drawn from this analysis as far as secularization is concerned and compare

them to the data obtained from the 1981 and 1990 World Value Surveys

I Direct correspontlence to res Lambert, Groups rle Sociologrle ties Religions er tie lo

CNRSJSPHE, ParisMany thanks to A- T. Larson and 5. Lo-ndquist, for the translation of the French orieiml; to A. Blast, J. Ruonz and

W- H. Simnosfor the

and, for their oomrnervs and rn'tio'.oru, to: F. Chrrrnpion, M. Cohen, K. Dobbdoere,

D. Heru'euLeger, F. l.ourrrion.J.-M. C)uee'roogo. G. l'vlichelor,J. Huone,_l'. Snorer. W. H- Santos, L. Tomasi. anal

thereferee.

303

r.rt|.l'l

ch

J

E

'\-I:

l'-.'I

II

r_'|

-1.

_n.

304 SOCIOLOGY or asuoton

(V/'VSs), and the 1991 International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) survey

dedicated to religion.

Obviously, our conclusion depends, in part on the ways in which we define

modernity, religion, and secularization. Without wishing to enter into the

debate on these questions, I will explain my definitions with the aim of

clarifying my approach and indicating the limits of my analysis. For religion, l

understand it in the most common sense of a group, organization, or institution

considering itself as such. This excludes secular religions but does not prevent

us from finding a religious dimension present in such ideologies. More precisely,

I will consider "religious" any practice or belief which refers to a superernpirical

reality, i.e., a reality radically exceeding the objective limits of nature and man,

provided that there is a symbolic relationship between man and this reality;

objective is used in the sense of the scientific process which characterizes the

point of view of the social sciences. This definition allows us to deal with

parallel beliefs" which are currently increasing in importance (telepathy,

astrology, fortune telling, spiritism, cosmic consciousness, energies, near death

experiences, and so on). They refer to a superempirical reality, and they will be

so

ll

considered as religious if they include a symbolic relationship with man, which is

the case of spiritism but not of astrology, which will be considered as

parareligious. For secularization, Peter Bergers (196?) definition seems to be the

most relevant to our purpose, and I will operationalize it by distinguishing two

thresholds of secularization: (1) an autonomization in relation to religious

authority while religious symbols remain salient and (Z) an abandonment of

religious symbols.

|.ucu_ipa-peatu

ul-

trr_1

o

E'u

t:|

Ii

tn

on

U

'--.

U

r.rt|.l'l

o

J

MODERNITY AS A NEW AXIAL PERIOD

E

'\-I:

l-J

_.

r_'|

_|

_n.

Several historians and philosophers have stressed the key role that certain

periods in history have played in developing techniques, political structures, or

worldviews which were to dominate the foreground of the next centuries or

millennia before being, in turn, questioned, then replaced, or altered and inserted into new systems.Man seems to have started again from scratch four times,"

Karl ]aspers wrote (1954: 3?-38): with the Neolithic age, with the earliest

civilizations, with the emergence of the great empires, and with modernity. Each

of these axial turns produced a general reshaping of the symbolic field," to use

Pierre Bourdieus tenn, and a great religious commotion which led to disappear-

ances, redefinitions, and emergences. Each period finally led to new religious

configurations, respectively: oral agrarian religions, religions of antiquity,

religions of salvation (tmiversalist religions), modern changes. Of the religions of

antiquity, only Judaism and Hinduism survived the preceding axial age, aheit

greatly changed and keeping typically pre-universalist traits (at least up to

modernity): a large number of prohibitions, important domestic rites, transmission by descent. We may assume that modernity also stands as a major

RELIGION IN MODERNITY as A NEW AXIAL not 305

challenge to established religions as well as a potential source of religious

innovation, especially if it is about to be radicalired and generalized, as Giddens

argues (1991). In addition, the hypothesis of modernity as a new axial turn leads

us to consider very long-term effects; this enables us to perform comparative

research, and proposes an interpretation accounting not only for religious

decline, but also for revivals, mutations, and inventions.

The concept of axial age" has been used to refer to one historical period:

the emergence of universalism, philosophy, great religions, early science (see,

e.g., ]aspers 1954; Bellah 1976:1050; Eisenstadt 1936; Hick 1939: Z1-35). This

is especially true of the sixth to fifth centuries BCE, which were a ltey stage in

this process (Deutero-Isaiah, the era of Pericles, Upanishads, ]ain, Buddha,

Confucius, Lao-Tre), of which Christianity and lslam are offsprings. This age is

considered as "axial" because we continue to be its heirs, particularly through

the great religions. However there is no reason that we cannot also consider the

Neolithic age, the earliest civilizations, the great empires, and modemity as such

axial ages, since they too marl: a general reshaping of collective thought.

Therefore, our definition of axial age" (or axial period) shall include these four

ages. At its beginning, an axial age is a kind of cinematic fade; it is marl-ted by

critical moments of crisis and shifts of thought which lead to a reshaping of the

symbolic field which creates a new period of stability. These critical phases vary

in duration from, for example, a thousand years for universalism (from the sixth

century BCE to the emergence of Islam) to several millennia for the Neolithic

age (from its first emergence to its eventual global expansion and triumph).

]aspers, while in fact considering modernity as being a new axial period,

regarded the turn taken by modernity in the nineteenth century as the harbinger

of a probable "second axial period (]aspers 1954: 38). He hesitated because

globalisation was not yet a widespread phenomenon when he first wrote this in

1949, although we can assume that this is the case today. ]aspers identified

modernity with four fundamental distinguishing features: modern science and

technology, a craving for freedom, the emergence of the masses on the historical

stage (nationalism, democracy, socialism, social movements), and globalisation.

We find it relevant to add to this list the primacy of reason (a point that ]aspers

implicitly includes in the four features), the development of capitalism, and

functional differentiation (the rise of the modern state, and Parsons's and

Luhmanns concept of differentiation of the spheres of activity in society).

This notion of axial age has not been utilized by sociologists to analyze

modernity. However Arpd Srakolczai and Laszlo Fiistos (1996) refer to the

axial age," and they use the concept of axial moment in ways that are

relevant to this analysis. They define this notion as follows: An axial moment

occurs whenever there is a global collapse of the established order of things,

including the political system, the social order of everyday life, and the system of

beliefs a very rare event and a major spiritual revival. . . . Such a period

happened in the first centuries (collapse of the Roman republic and rise of

so

ll

|.uo.|_ipa-pa-o1u

in

rtu

o

E'u

1:|

Ii

Ll'l

no

U

'--,

l

1.rt|.l'l

o

J

E

'\-I:

I-.'I

_.

t_'|

-1.

_n.

306 soctotosr or RELIGION

Christianity), in the fifth-seventh centuries (collapse of the Roman Empire and

rise of Islam), in the fifteenth-sixteenth centuries (the waning of the Middle

Ages, Renaissance, and Protestantism), and finally the two majors stages of the

dissolution of absolutist politics and the traditional European social order,

Enlightenment and socialism." Thus, that which they choose to define as an

axial moment corresponds to key phases that occur within an axial age. For

example, the rise of Christianity and of Islam are two key phases of the previous

axial age (universalism), and the fifteenth-sixteenth centuries, the Enlightenment, and socialism (or more accurately the rise of industrial society) are the

three key phases of modernity. Nonetheless, l believe that it is useful to employ

the term axial moment to define such phases within an axial period.

In a very schematic fashion we can therefore period ire modernity. It begins

with this axial moment of the fifteenth-sixteenth centuries, which is not only

the beginning of what historians call the modern age, but also that of modem

science, and of the birth of capitalism and the bourgeoisie. But modernity only

becomes a major phenomenon at the end of this period with the Enlightenment,

the English and, especially, the American and French Revolutions, the birth of

scientific method and thought, and the birth of industry (second axial moment).

The third axial moment should include the development and triumph of indus-

trial society and of capitalism (nineteenth-mid-twentieth centuries), first in

England, and then throughout Europe and North America, the development of

socialism, the building of the natiotnstate, the spread of nationalism and

colonialism to its breaking point with the two world wars, and finally,

decolonisation, globalisation and, in the West, the triumph of democracy, of the

affluent society, and of the welfare state. Modernity also resulted in the Cold

War and the threat of nuclear destruction. The 19695 are often considered as a

turning point: the beginning of the so-called post-industrial, post-fordian

society, the information or knowledge society, and the beginning of the moral

revolution. Ever since, the tertiary sector has become increasingly dominant,

intangible factors of production (information, communication, and knowledge)

and new technologies (computers and electronics) have become more important; and the family is becoming less and less traditional. ln addition, globalisation is complete, the middle class is getting more and more powerful, new

problems (unemployment and pollution) and new social movements (feminism,

regionalism, ecology, etc.) are emerging, and finally, Communism has collapsed.

Are we still in the era of modernity or in postmodernityl I share the opinion

of Anthony Giddens (1991;3) who writes that rather than entering a period of

post-modern ism, we are moving into one in which the consequences of

modernity are becoming more radicalired and universalired than before." In fact,

that which is supposed to define postmodemity is far from featuring these

fundamentally new traits that characterise an axial turn, but could constitute a

new axial moment" (as Sralcolczai thinks) that could be explained in terms of

generalised, radicalized, and reflexive modernity. The hallmark of postmodemity

|.uo.|_ipa-pee;ui.og

L|'\I

I'D

u

o

.51

u

:1

in

to

U

'--,

I'_|

1rt|.l'l

o

J

E

'\-I:

I-J

_.

\'_'l

_e

RELIGION [N MODERNITY as A New AXLAL soc 30?

is the disqualification of great narratives: great religions, great ideologies

(nationalism, Communism, fascism), and the ideology of endless progress. But

this only allows us to differentiate ourselves from the prior phase (axial moment)

of modernity, and it is partly refuted by new forms of nationalism and by

religious fundamentalism. The relativization of science and technology is not

new, but is increasing precisely because the excesses and dangers of the former

are becoming dramatically threatening (nuclear threat, pollution). One could

continue and show that the other features attributed to postmodernity are the

logical extension of trends within modernity, as are the nuclear threat and

pollution: the detraditionalization of the life-world, the anthauthoritarian

revolt, hedonism, new social movements, and above all, individualization. The

same even holds true for the selective return to certain traditions, once

modernity has prevailed over tradition, or for the repeated claim to local

identities, which is a reaction against globalization. So I agree with Becltfords

criticism (1996: 304?) of the concept of postmudernity.

ln spite of all of this, l remain open to the hypothesis that we should be on

the edge of some form of postmodernity. at least in a deeply new moment in

modernity, because the risk of irreparable pollution and, above all, of nuclear

destruction is the most dramatic and the most radical fate we can imagine

insofar as the very survival of the human species is at stake; this actually is a

fundamentally new trait. Besides, if we consider modernity as a new axial period,

we cannot know where we are in this process, so much the more as modernity

involves permanent change, even change at an accelerated pace, so that it might

not be followed by a phase of stabilization, as was formerly the case. Thus, it

could create some kind of permanent turn. Anyway, since an axial turn is a

cinematic fade in which older forms can coexist for centuries with new forms or

survive by adopting new forms, it would be very difficult, while we are on the

inside of this fade, to distinguish the decline of modernity from the birth of

postmodernity. At present, we do not have the necessary distance to resolve the

matter, but in any case, whether we are in postmo-dernity, late modernity,

hypermodernity, or whatever other term one might choose, it does not change

anything concerning our method of analysis.

GLOBAL ANALYSES OF THE DISTINGUISHING

RELIGIOUS FEATURES OF MODERNITY

The intent of this section is to review the various claims that have been

made concerning the effects of modernity on religion and the transformations

that are taking place in religion. l will not attempt to link these analyses in a

systematic way, as that is the task of the following section. I am reasonably

sure, said B-ellah (1976: 39), that even though we must speak from the midst of

it, the modern situation represents a stage of religious development in many

|.uo.|_ipa-pee;u1.or]

ir-

rtu

o

E'u

1:|

Ii

Ll'l

no

U

'--,

U

rrt|.l'l

o

J

E

'\-I:

I-J

_.

r_'|

_|

_n.

RELIGION IN MODERNITY AS A NEW AXIAL AC-E

329

secular and that only one is predominantly religious. Unfortunately, they do not

give the religious characteristics of these different value types.

The factor analyses of correspondences between religious variables always

point to the existence of three different focal areas which we can call: (1)

confessing Christ ianiry according to Dietrich Bonhoeffefs definition (following

Keri-tofs 1988), which is to say the Christianity of faith in God; (2) cultural

Christianity (i.e., a question of identity), meaning little personal involvement,

rites of passage; and (3) secular humanism (Lambert 1996). lt is significant that

the notions of personal God," spirit, life force, and nonbelief in God are

respectively linked to the three focal areas (agnosticism comes somewhere

between the last two). lt is also worth noting that the less people believe in God

in a country, the less the God they believe in is a personal God, and the less God

is important in their lives. Confessing Christianity is predominant in the United

States, Ireland, Italy, and to a lesser extent in Portugal. Confessing Christianity

and culttual Christianity are on equal footing in Canada, Spain, Greece,

Luxembourg, and Ciennany. The majority of the French, Belgians, English, and

Dutch are divided between cultural Christianity and secular humanism. The

Scandinavian countries, where Christianity is more a civil religion, are largely

dominated by cultural Christianity.

|s.uo.|_ipa-peoqui.or]

I121

A general evaluation of secularization

o

E'u

1:|

Ii

Ll'l

It appears that the first rhreslwld of secularization was largely crossed in the

West with the coming of modernity, at three different levels.

(a) The macro level. States affirmed their autonomy in relation to religious

no

institutions, even while they kept a civil religion (the United States) or a link

'\-I:

with a particular denomination (Anglicanism in England, Lutheranism in

Sweden). Political parties did the same, even when they kept a religious label

(ChristianDemocrat). Opposite attempts have failed politically (the Moral

Majority). At the global level, the social bond rests first with democracy and

human rights, and not with religion. In Europe, the current tendency is one of a

weakening relationship between the state and the church in the countries that

were most linked to a denomination, and of a strengthening relationship in the

case of laicity and, above all, in the case of the former communist countries. For

instance, the Catholic church has been disestablished in Spain and Portugal;

Sweden is ending the automatic affiliation of newborns with Lutheranism (when

the parents did not express the desire for a different denomination). On the

contrary, in France, the legitimacy of Catholic schools is no longer questioned,

public schools are more open to religious culture, representatives from the main

religions and denominations are members of the National Consultative Ethics

Commitee (bioethics), not to mention Mitterrands state funeral in Paris's

Notre-Dame Cathedral; in the former communist countries, the churches cannot recover an authoritarian or monopolistic role, as Poland evidenced when the

'--.

U

rrt|.l'l

o

J

E

I-J

_.

\'_'l

_c

330 socrotoor or RELIGION

left won the elections. In any case, there is no clear relationship between the

denominational systems and the religious states, with the most interesting

example being that of the Scandinavian cotmtries, which have very low levels of

Christian religiosity (Lambert 1996).

lb) The meso level. With respect to schools and education, diverse situations

exist. Sometimes schools follow a religious authority while nonetheless aligning

their programs with national norms, sometimes they are autonomous. However,

most often they dispense a religious education (except in the cases of laicity or

laic pillars). As for culture, in the general sense of the arts, intellectual life, and

the media, we know that these sectors are for the most part autonomous with

relation to religious institutions.

(cl The individual level. If we were to judge by the degree of autonomy that

those who belong to a religion give themselves (according to the surveys], we

can see that institutional secularization is strong on an individual level as well.

This does not, however, prevent individuals from taking into account, in their

own way, the positions of their religious authorities. Furthermore, we note a

so

ll

strong desire to desecularize society (|"lervieu'l.eger 1993) within fundamem

talist, evangelical, Pentecostal, and charismatic groups, but as we have noted,

their reach is, with the exception of Poland, rather limited.

What about the secrmd tlrresholdi Contrary to the preceding one, this

threshold has been crossed only in a limited manner except, formerly, in the

communist countries and, today, in certain spheres and among the youth of

some countries, although it depends in part on the definition of the religious.

Besides, the idea that religion would tend to disappear with modernization has

declined, if not disappeared.

(al The macro level. Only several states have removed all religious references

from their constitutions (France, for example). On the contrary, Eastern

European countries and Russia, which had largely crossed the threshold on a

very hostile note, are returning either toward the rst one after the collapse of

Communism, or toward the more benevolent or neutral second one. We even

can observe that religion has played an important role in rebuilding the civil

society and the state in several countries, especially Poland (Casanova 1994-)(b) The meso level. Among the spheres of activity, only science and

economics have clearly passed this threshold, but this do-es not necessarily mean

that religion has been rejected in itself. Health and social services have more or

less crossed this threshold according to the country and, as we know, only in the

case of laicity or pillariration, as is the case with schools. Culture functions

largely autonomously in relation to religion, knowing that religious culture has

its proper place within the sphere of culture.

(c) The individual level. We have noted two opposite tendencies since the

1970s that differentiate the oldest from the youngest generations (Lambert 1993,

1996; Lambert and Voy 1997): on one hand, an increase in the percentage of

the nonreligious, and a decrease in the belief in God, less in the United States,

|.uo.|_ipapeoqu

L|'I

I'll

U

ch

E'U

:|

Ii

Ll'l

so

U

*--.

E

1.rt|.l'l

1:J

'\-C

r-J

t_'I

_|

_n.

RELIGION IN MOIJERNITY as A new AXIAL not 331

more so in Europe (with a majority of nonreligious young in France, Great

Britain, and Netherlands); on the other hand, a stability in belief in miracles

and in an afterlife, a spread of NR!/ls, and above all, a growth in parallel beliefs,

self-spirituality, loosely organised groups, "believing without belonging" (Davie

1995), such that approximately one-third of the nonreiigious have in fact

religious or parareligious beliefs. The balance depends upon the status we give to

these parallel beliefs and new religious forms. It is the same in the former

communist countries, where the return to religion is more limited than it first

seemed to be and where the nonreligious remain a majority in Russia, the former

East Germany, and Bulgaria, but where these parallel h-cliels and new religious

forms are spreading as well.

We can then conclude that, for the first threshold, there already exists a

widespread secularization and it is progressing. For the second threshold, secular-

ization is limited to some states, spheres, turd subpopulations, noting that, on an

individual level, it depends upon the status and importance of the parallel

beliefs, the self-spirituality, the seeker spirituality, the loose networks, knowing

that the spread of NRL/ls remains a very minor phenomenon, except if we

include the New Age-type nebula. The problem is best illustrated by the case of

Dutch youth (]anssen 1993), of whom, according to a 1991 national survey, only

39 percent belong to a religion, but 16 percent can be qualified as being

influenced by New Age or Eastern religions, l3 percent are doubters, 16 percent

are only praying, and a mere 8 percent are nonbelievers. Surprisingly, B2 percent

so

ll

|.uo.|_ipope-o1u

L|'\I

I'll

r_1

o

E'r_1

1:|

E

Ll'l

pray at least sometimes and, among the nonchurchgoers, prayer is the most

to

persistent religious element but only in a rather psychological and meditative

way: to give strength, to accept the inevitable such as the death of a relative, as a

release or as a time to ponder, in keeping with a primarily impersonal concept of

the divine. Do these findings point to a stage of religious decomposition, to a

'\-I:

minor form of religiosity (a vague bacl-td top, comforting beliefs], or to the seeds

of possible reconfigurations? Are all of the parallel belief systems religious? If we

keep our two criteria to define the religious (a superempirical reality and a

symbolic relationship along with it}, we will then exclude astrology and

numerology for instance, but not the beliefs and practices of the Dutch youth,

except a few of them.

Whatever the case might be, we are left to wonder whether or not we might

be in the middle of an evolution toward a third threshold that we could define as

pluralistic secularization," in which religion has the same ascendancy upon

society and life as any other movement or ideology, but can also play a role

outside of its specic function and have an influence outside of the circle of

believers as an ethical and cultural resource, as lames Beclrfotd stressed (1989)

-- as it is illustrated here in the case of major causes." Once again, this seems

possible only if religion can respect individual autonomy and democratic

pluralism. We can also mention again Casanovas analysis, which illustrates this

new public role of religion, but we would balance his stress on deprivatiration

'--,

r.rtm

0

J

E

I-.'I

II

r_'|

-1.

_n.

332 socrot-my or RELIGION

with his own observations concerning the conditions for this role: the acceptance of pluralism and of functional differentiation. This new threshold would

correspond to a step beyond the conflicts that were linked to the long and

difficult redefinition of religion s place in modernity.

REFERENCES

Picquaviva, 5. S. l9?9. The decline of the sacred in industrial society. Oxford: Blackwell.

Barker, E. I936. Religious movements: Cult and anti~cult since jonestown. Annual Review of

Sociology ll: 32946.

Baubrot, J. 1990. Vers an riouveau pacte laiqrier Paris: Scuil.

Bcclrford, 1. 1984. Holistic imagery and ethics in new religious and healing movements. Social

Compass 31: Z5942.

--i. 1996. Postmodemity, high modernity, and new modernity: Three concepts in search of

religion. In Postrnixlcmiiy, sociology, and religion, edited by K. Flanagan and P. C. ]upp, .:O*4'?.

London: Macmillan.

Bellah, R. N. 1976. Beyond belief: Essays on religion in a posorraditional world. New York: Harper Gr

Row.

Berger, P. 196?. The sacred canopy. New York: Doubleday.

|-is

.uo.|_ipa-pe-o1ui.or]

i-. 1994. Religion and globalization. London: Sage.

Campichc, R., et al. 1992. C-roire en Snissefsl. Lausannc: lfhge dhornrne.

Champion, F. 1993. La nbuleuse mystique-esoterique. In De Frnorion en religion, edited by F.

Champion and D. Hervieu-Leger, 18-6'9. Paris: Centurion.

o

Er_1

i:|

E

Ll'l

Casanova,

'--.

1994. Public religion in the modern world. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Davie, Ci. 1996. Religion in Britain since I945. Oxford: Blackwell.

Dobbclacrc, K. I981. S-coulariration: A multi-dimensional concept. Current Sociology 29(2): l-213.

i. 1995. Religion in Europe and North America. In Values in weslarrn societies, edited by R.

dc Moor, L29. Tilburg: Tilburg University Press.

Dobbelaere, K., and W. lagodzinslti. 1995. Secularization and church religiosity (chapter 4),

Religious Qgnition's and beliefs (chapter ?}, Religious and ethical pluralism (chapter BI. In

The impact of values, edited by ]. W. V. Deth and E. Scarbrough. Oxford: Oxford University

Press

Eisenstadt, S. 1936. The orr1'gins and diversity of axial age civilizations Albany: State University of

New York Press.

Ester, P., L. Halrnan, and R. de Moor. 1993. The irlrlividualizing society: Value change in Europe and

North 1'-lunerica. Tilburg: Tilburg University Press.

Flanagan, l(., and P. C. _Iupp. i996. Postmodernity, sociology, and religion London: lvlacmillan.

Giridens, A. 1991. The coruequences of modemity. Cambridge, MA: Polity Press

Heelas, P. I996. De-traclirionalisation of religion and self: The new age and postmodernity. In

Postmoderniry, sociology, and religion, edited by K. Flanagan and P. C. jupp. London:

Macmillan

l-iervieu-Leger, D. 1993. Present-day emotional renewals: the end of secularization or the end of

religion? In A future for religion? New paradigms for social analysis, edited by W. H. Swatos,

I29-14-3. London: Sage.

Hervieu-Leger, D., with F. Champion. 1986. Vets an clwislianisme nouvcau? Paris: Cerf.

Hick, ]. 1989. An interpretation of religion. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

larmacorme, L. R. I992. Religious markets and the economics of religion. Social Compass J9:l23Jl

I-

rtr_1

no

U"

r.rt\.l'l

cJ

E

-=I-.'I

_.

II

l'_'|

_-.

_s

RELIGION IN MODERNITY ASA new Axial. AGE 333

janssen ]. I993. The Netherlands as an experimental garden of religiositjt Remnants and renetvals.

Social Compass 45: 10143.

]aspers, K. 1954. Origins er sens dc lhistoire. Paris: Plon. {English ed. I953. The origin and goal of

lllillji. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press-l

l(erl:]10fs,_l. I933. Between Christendom and Christianitv._l(mrnal of Empirical Tliealog Z: 33-101.

Kitagavra, J. M. 196?. Primitive, classical, and modern religions. In Tllc history of religion. Essays on

p-mlrlcms of undersumding, edited by J. M. Kiragavra. Chicago. IL: University of Chicago Press.

Kurte, L. 1995. Gods in the global villag: The world's religions in a sociological perspective. London:

Pine Forge Press.

Lambert, Y. I955. Dieu elurnge en Bretagne. Paris: Cerf.

--. 1993. Ages, generations er Chrisrianisme, en France et en Europe. Revue Francoise de

Sociulogie Z4: 525-55.

i. I996. Denominational svsrems and religious states in the countries of Western Europe.

Research in clre Social Scientific Study of Religion F: 11T43.

i. 1998. The scope and limits of religious functions according to the European value and

ISSP surveys. In On seculmizarion: Homage to Karel Doiabelaere, edited by ]. Billier and R.

Laennans. Leuven: University Press of the Catholic University.

Lambert, Y., and I... Vov. 199?. Le-S crosanees dcs jeunes Europens. ln Cultures jeunes er religions

en Europe, edited by R. Campiche, 91166. Paris: Cerf.

so

ll

Luhmann, N. 19?? Fttnlttltlri ti-er religion Frankfurt: Sulirlcamp.

i. 1981. The cli_'erentiaiior1 ofsociery. New Yorlcz Columbia University.

Martin, ll A. l9?il. A general dreary ofsecttlaiitaiiort Oxford: Blackwell.

Melton, ]. G. I998. Modern alternative religions in the west. In A new l1.a'n-dlrooli of living religions,

edited bv ]. R. Hinnels. I-larrnoridwortl1,UK: Penguin.

Nalramura, H. 1986. A ctnnparaave hismry of ideas. London: Routledge.

Roof, W. C. 1993. A generation of seel-re-rs. San Francisco, CA: Harper.

Roof, W. C, ]. W. Carroll, and D. A. Rooeen, eds. 1995. The post-war generation and estalrlisrrlent

religion. Boulder, CO: Wesiview Press.

Seakolcaai, A., and L. Fiistiis. l9o. Value systems in axial n1on:ienLs: A comparative aiialvsis of Z4

European countries. EU] Wnrlting Paper N 96l3. Florence: European University Institute.

Tschannen, O. I992. Les theories de la scularisarion. Gencve: Drtrr.

Walter, T. i996. The eclipse of eternity; A sociology of the sfrerlije. London: Macmillan.

Wallis, R. 1934. Elemema11r_fonns ofnew religions life London: Routledge.

Willaime, ].P. 1995. Sociologie des religions. Paris: PUF.

|-'is

.uo.i_ipa-peeru

I'D

U

-:i

Er_1

i:|

E

Ll'l

an

U"

'--.

l

1.rt\.l'l

cJ

E

-e"

l-J

II

r_'I

-1.

_n.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Gellert, M - The Eruption of The Shadow in NazismDocument15 pagesGellert, M - The Eruption of The Shadow in NazismvffinderPas encore d'évaluation

- The Neoliberal Era Is EndingDocument12 pagesThe Neoliberal Era Is EndingvffinderPas encore d'évaluation

- Dunn. J - The Living WordDocument200 pagesDunn. J - The Living Wordvffinder100% (2)

- How Nazism Exploited A Basic Truth About HumanityDocument4 pagesHow Nazism Exploited A Basic Truth About HumanityvffinderPas encore d'évaluation

- How Nazism Exploited A Basic Truth About HumanityDocument4 pagesHow Nazism Exploited A Basic Truth About HumanityvffinderPas encore d'évaluation

- Dhiman, S - Parables of LeadershipDocument11 pagesDhiman, S - Parables of Leadershipvffinder100% (1)

- Huggins, R - The Ox and The DonkeyDocument15 pagesHuggins, R - The Ox and The DonkeyvffinderPas encore d'évaluation

- Everts, J - Pentecostal Theology and The Theological Vision of N.T. WrightDocument208 pagesEverts, J - Pentecostal Theology and The Theological Vision of N.T. Wrightvffinder100% (6)

- Stenger, V - Quantum QuackeryDocument4 pagesStenger, V - Quantum Quackeryvffinder100% (1)

- Scharf, D - Pseudoscience and Stenger's Gods PDFDocument34 pagesScharf, D - Pseudoscience and Stenger's Gods PDFvffinderPas encore d'évaluation

- Huggins, R - The Ox and The DonkeyDocument15 pagesHuggins, R - The Ox and The DonkeyvffinderPas encore d'évaluation

- Lossky, W - Introduction To Apophatic TheologyDocument5 pagesLossky, W - Introduction To Apophatic TheologyvffinderPas encore d'évaluation

- Dhiman, S - Parables of LeadershipDocument11 pagesDhiman, S - Parables of Leadershipvffinder100% (1)

- Lossky, W - Introduction To Apophatic TheologyDocument5 pagesLossky, W - Introduction To Apophatic TheologyvffinderPas encore d'évaluation

- Dhiman, S - Parables of LeadershipDocument11 pagesDhiman, S - Parables of Leadershipvffinder100% (1)

- Bonz, M - The Gospel of Rome vs. The Gospel of JesusDocument6 pagesBonz, M - The Gospel of Rome vs. The Gospel of JesusvffinderPas encore d'évaluation

- Whidden, D - The Alleged Feudalism of Anselm's Cur Deus Homo PDFDocument33 pagesWhidden, D - The Alleged Feudalism of Anselm's Cur Deus Homo PDFvffinderPas encore d'évaluation

- Kingship CundallDocument11 pagesKingship CundallIonel BuzatuPas encore d'évaluation

- Lekavod Shabbos Magazine Devarim 5779Document28 pagesLekavod Shabbos Magazine Devarim 5779vffinderPas encore d'évaluation

- Carr, D - The Formation of The Hebrew Bible PDFDocument537 pagesCarr, D - The Formation of The Hebrew Bible PDFvffinder100% (1)

- The Beauty of The Cross PDFDocument228 pagesThe Beauty of The Cross PDFmikayPas encore d'évaluation

- Cezula, N - God and King in Samuel and Chronicles PDFDocument88 pagesCezula, N - God and King in Samuel and Chronicles PDFvffinderPas encore d'évaluation

- Bethancourt, P - Christ The Warrior King PDFDocument54 pagesBethancourt, P - Christ The Warrior King PDFvffinderPas encore d'évaluation

- Bryson, M - The Tyranny of HeavenDocument276 pagesBryson, M - The Tyranny of HeavenvffinderPas encore d'évaluation

- Cezula, N - God and King in Samuel and Chronicles PDFDocument88 pagesCezula, N - God and King in Samuel and Chronicles PDFvffinderPas encore d'évaluation

- Kingship CundallDocument11 pagesKingship CundallIonel BuzatuPas encore d'évaluation

- Aupers, D - Chistian Religiosity and New Age PDFDocument10 pagesAupers, D - Chistian Religiosity and New Age PDFvffinderPas encore d'évaluation

- Fahy, P - Origens of PentecostalismDocument132 pagesFahy, P - Origens of PentecostalismvffinderPas encore d'évaluation

- Bratcher, D - God As A Jealous God PDFDocument2 pagesBratcher, D - God As A Jealous God PDFvffinderPas encore d'évaluation

- The Fool and The MadmanDocument5 pagesThe Fool and The MadmanvffinderPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- TOP233YDocument24 pagesTOP233YJose BenavidesPas encore d'évaluation

- DHT, VGOHT - Catloading Diagram - Oct2005Document3 pagesDHT, VGOHT - Catloading Diagram - Oct2005Bikas SahaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lcnews227 - Nexera SeriesDocument47 pagesLcnews227 - Nexera SeriesMuhammad RohmanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Ecological Effects of Eucalyptus PDFDocument97 pagesThe Ecological Effects of Eucalyptus PDFgejuinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Vol07 1 PDFDocument275 pagesVol07 1 PDFRurintana Nalendra WarnaPas encore d'évaluation

- DIY Paper Sculpture: The PrincipleDocument20 pagesDIY Paper Sculpture: The PrincipleEditorial MosheraPas encore d'évaluation

- English 8 - B TR Và Nâng CaoDocument150 pagesEnglish 8 - B TR Và Nâng CaohhPas encore d'évaluation

- AnamnezaDocument3 pagesAnamnezaTeodora StevanovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Mid-Year Examination, 2023 Science Year 7 1 HourDocument23 pagesMid-Year Examination, 2023 Science Year 7 1 HourAl-Hafiz Bin SajahanPas encore d'évaluation

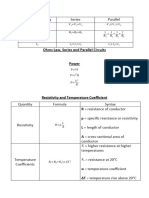

- EET - Formulas - Christmas TermDocument3 pagesEET - Formulas - Christmas TermJMDPas encore d'évaluation

- 1mrk513011-Ben en Auxiliary Current Transformer For Radss 1-Phase and 3-Phase Slce 12 Slce 16 Slxe 4Document4 pages1mrk513011-Ben en Auxiliary Current Transformer For Radss 1-Phase and 3-Phase Slce 12 Slce 16 Slxe 4GustavoForsterPas encore d'évaluation

- Primakuro Catalogue Preview16-MinDocument10 pagesPrimakuro Catalogue Preview16-MinElizabeth LukitoPas encore d'évaluation

- ScilabDocument4 pagesScilabAngeloLorenzoSalvadorTamayoPas encore d'évaluation

- Menstrupedia Comic: The Friendly Guide To Periods For Girls (2014), by Aditi Gupta, Tuhin Paul, and Rajat MittalDocument4 pagesMenstrupedia Comic: The Friendly Guide To Periods For Girls (2014), by Aditi Gupta, Tuhin Paul, and Rajat MittalMy Home KaviPas encore d'évaluation

- Smart Watch User Manual: Please Read The Manual Before UseDocument9 pagesSmart Watch User Manual: Please Read The Manual Before Useeliaszarmi100% (3)

- Soal Bahasa Inggris X - XiDocument6 pagesSoal Bahasa Inggris X - XiBydowie IqbalPas encore d'évaluation

- Color Codes and Irregular MarkingDocument354 pagesColor Codes and Irregular MarkingOscarGonzalezPas encore d'évaluation

- Varaah KavachDocument7 pagesVaraah KavachBalagei Nagarajan100% (1)

- BHLP Year Long Plan Required English Medium 2023 24 Batch Final 991676721629413Document3 pagesBHLP Year Long Plan Required English Medium 2023 24 Batch Final 991676721629413A V GamingPas encore d'évaluation

- CAT25256 EEPROM Serial 256-Kb SPI: DescriptionDocument22 pagesCAT25256 EEPROM Serial 256-Kb SPI: DescriptionPolinho DonacimentoPas encore d'évaluation

- What's The Use of Neuroticism?: G. Claridge, C. DavisDocument18 pagesWhat's The Use of Neuroticism?: G. Claridge, C. DavisNimic NimicPas encore d'évaluation

- Tech Manual 1396 Rev. B: 3.06/4.06" 15,000 Psi ES BOPDocument39 pagesTech Manual 1396 Rev. B: 3.06/4.06" 15,000 Psi ES BOPEl Mundo De Yosed100% (1)

- Scientific Exploration and Expeditions PDFDocument406 pagesScientific Exploration and Expeditions PDFana_petrescu100% (2)

- Fantasy AGE - Spell SheetDocument2 pagesFantasy AGE - Spell SheetpacalypsePas encore d'évaluation

- Toptica AP 1012 Laser Locking 2009 05Document8 pagesToptica AP 1012 Laser Locking 2009 05Tushar GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Non-Pen MountDocument17 pagesNon-Pen MountT BagPas encore d'évaluation

- Catalogue: Packer SystemDocument56 pagesCatalogue: Packer SystemChinmoyee Sharma100% (1)

- Phytoremediation Acuatic PlantsDocument120 pagesPhytoremediation Acuatic PlantsFranco Portocarrero Estrada100% (1)

- Latihan Soal BlankDocument8 pagesLatihan Soal BlankDanbooPas encore d'évaluation

- The Immediate Effect of Ischemic Compression Technique and Transverse Friction Massage On Tenderness of Active and Latent Myofascial Trigger Points - A Pilot StudyDocument7 pagesThe Immediate Effect of Ischemic Compression Technique and Transverse Friction Massage On Tenderness of Active and Latent Myofascial Trigger Points - A Pilot StudyJörgen Puis0% (1)