Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Scapegoating and Leader Behavior

Transféré par

ites76Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Scapegoating and Leader Behavior

Transféré par

ites76Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Social Forces, University of North Carolina Press

Scapegoating and Leader Behavior

Author(s): James Gallagher and Peter J. Burke

Reviewed work(s):

Source: Social Forces, Vol. 52, No. 4 (Jun., 1974), pp. 481-488

Published by: Oxford University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2576991 .

Accessed: 02/11/2012 22:30

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Oxford University Press and Social Forces, University of North Carolina Press are collaborating with JSTOR

to digitize, preserve and extend access to Social Forces.

http://www.jstor.org

Scapegoatingand Leader Behavior*

University of Maine

Indiana University

JAMES GALLAGHER,

PETER J. BURKE,

ABSTRA CT

This article examines how the alternatives of scapegoating or social-emotional leadership are determined

in small discussion groups. The hypothesis asserts that the alternative "selected"by the group depends

on whether the task leader supports the low-status member. An experiment designed to test this

hypothesis indicated that scapegoating of the low-status member occurs when the task leader is somewhat hostile toward him. However, social-emotional leadership was not more in evidence when the task

leader supported the low-status member. Instead, such support had the unanticipated consequence of

increasing the task leader's legitimacy in performing task activity, thus decreasing both scapegoating

and social-emotional leadership.

The research reported here probed the mechanisms behind hostility transference in a small,

task-oriented group. The hypotheses are based

on Bales and Slater's (1955) model of role

differentiation as modified by Burke (1969).

The research included (1) a partial replication

of Burke's study identifying the scapegoat phenomenon, and (2) a test of one mechanism

hypothesized to account for that phenomenon.

Bales and Slater (1955) proposed a model

of emergent group structure which they termed

"role differentiation." When a group attempts

to achieve a goal by means of coordinated

interaction, inequality in task-oriented participation develops, and an individual who is

highly active (i.e., becomes a task leader) may

provoke hostility and tension. The reasoning

here is that if one person engages in "too

much" task-oriented activity (Burke, 1968),

he violates the norms of equality by limiting

the opportunities for other group members to

engage in this activity; hence, tension and hostility arise.

Bales and Slater view hostility and tension

as factors which may be handled either through

the emergence of a social-emotional specialist

who actively seeks to reduce tensions and hostilities, or the emergence of a scapegoat on

* An earlier version of this paper was presented

at the 1971 meeting of the Canadian Sociology

and Anthropology Association. The research was

carried out in part under a grant from National

Science Foundation, GS 2742.

[481]

whom hostilities and tensions may be spent.

for example, has sugBales (1953:147-8),

gested that:

The idea man [task leader] is the one most prone

to equilibrium-disturbingacts through his constant

movement toward the instrumentalgoal, and hence

he is most likely to arouse hostility. The value of

the role he plays is so great to the group, however, there are severe limitations on the amount of

hostility which can be directed toward him, and

as a result, much of it may be displaced onto

someone with low status.... the displacement of

hostility on a scapegoat at the bottom of the status

structure is one mechanism, apparently, by which

ambivalent attitudes toward the instrumental-adaptive specialist may be diverted and drained off.

Burke (1969) found that scapegoating of the

low-status member as a response to a high output of task activity on the part of the task

leader appears to occur, and under the same

conditions as do task and social emotional role

when the task-oriented

differentiation-i.e.,

activity has a low level of legitimation. Furthermore, these two responses-scapegoating

to be compleand role differentiation-tend

mentary alternatives: one occurs at the expense

of the other.

To explain the nature and determinants of

this complementary arrangement BuLrke(1969:

166) suggested some possible factors:

(1) whether or not there appears to be a group

member who makes a good scapegoat because of

some personal characteristic in addition to his

just being the low-status member; or (2) whether

or not there is a group member who has the per-

482 / SOCIALFORCES/ vol. 52, june 1974

sonal characteristicswhich allow him to play the

role of expressive leader thus leading to role differentiation; or (3) whether the task leader tends

to be supportive of the low-status member or not.

Though analysis of the present data seems to support the third alternative, with the present small

sample of low legitimation groups, it is virtually

impossible to adequately check any of these possibilities.

From the above, we may say that possible

mechanisms fall into two broad categories,

psychological and structural, the latter consisting of factors which legitimate scapegoating

within the group. Although an adequate theory

of scapegoating must include both levels, this

research concentrates on the structural.

THEORY

We may now outline a proposed theory of the

emergent role structure in a task-oriented group.

1. As a group works toward achieving a particular goal, unequal distribution of taskoriented activity will occur among group members.

2. If the task leader's activity goes beyond

the legitimate, expected level, this activity will

stimulate tension and hostility within the group.

3. Although the task leader is the source of

tension and hostility, he will tend not to be

its object because adequate performance of his

role is necessary for goal attainment.

4. Either of two roles may emerge: scapegoat or social-emotional leader. These roles

function either to drain off or redirect the hostility and tension.

5. These roles stand in a complementary

relationship to one another such that

(a) A scapegoat will emerge if such a role

is legitimized by the task leader through a style

of interaction which is nonsupportive of or

hostile toward the low-status member of the

group.

(b) A social-emotional leader will arise if

the task leader supports the low-status member

and if the group includes an individual able to

give social-emotional leadership.

Following the propositions outlined above,

specific hypotheses concerning the impact of

experimental conditions on development of the

roles of scapegoat and social-emotional leader

may now be stated:

1. If the task activity of the task leader goes

beyond the legitimate, expected level, and if

the task leader is somewhat hostile to the lowstatus member, then the amount of hostility

directed toward the low-status member by

members other than the task leader will be

significantly greater than if the task leader is

neutral or somewhat supportive of the lowstatus member.

2. If the task activity of the task leader goes

beyond the legitimate, expected level, and if

the task leader is neutral or somewhat supportive of the low-status member, then the

perceived performance level of social-emotional

activity by the social-emotional leader will be

greater than if the task leader is somewhat hostile toward the low-status member.

In addition to these two primary hypotheses

we may state two corollary hypotheses. From

propositions three and four above we conclude

that there ought to be an inverse relationship

between hostility toward the task leader and

development of the roles of scapegoat and

social-emotional leader. Thus:

3. If the task activity of the task leader goes

beyond the legitimate, expected level, and if the

task leader is somewhat hostile to the lowstatus member, then the correlation between

the amount of hostility directed toward the

task leader and that directed toward the lowstatus member will be negative and different

from zero.

4. If the task activity of the task leader goes

beyond the legitimate, expected level, and if the

task leader is neutral or somewhat supportive

of the low-status member, then the correlation

between the amount of hostility directed toward

the task leader and the perceived performance

level of social-emotional activity by the socialemotional leader will be negative and different

from zero.

PROCEDURES

Groups

Twenty-five 5-person groups were scheduled.

They included both male and female student

volunteers from the Junior Division (freshmen

and sophomores) of Indiana University. All

subjects were randomly assigned to their specific groups. The task of each group was to

Scapegoating

create an outline of a Liniversity-level course in

Social Problems. Each group was given onehalf hour for discussion.

Experimental Conditions

Both positive and negative support conditions

were achieved through the use in each group

of a confederate who acted as a strong task

leader. The same person acted as the confederate in all groups. Under both conditions

the confederate was instructed to take control

of the group immediately. Through the discussion he maintained his role by constantly

guiding and directing the group toward the

goal. The confederate was also instructed to

use the first ten minutes of the thirty-minute

discussion to identify the low-status member

of the group. Following Bales (1953) we defined status according to activity; therefore, the

least active member was designated as the lowstatus member. Under the negative support condition, the task leader began to direct some hostility toward the low-status member after the

initial ten-minuLteperiod.1 Under the positive

support condition, the task leader began to provide some support of the low-status member. Regardless of the condition, he was instructed to

show no hostility toward any other member

of the group. The level of hostility (or support) involved was small and not unusual for

discussion groups of this sort. The important

point is that the conditions were relatively

controlled.

To achieve a relatively low degree of legitimation of task activity (thus making any high

level of task activity "excessive"), procedures

used in Burke ( 1969) were adapted. We began

by assuming that the degree of legitimation

of the task leader's activity would depend on

the degree to which the members of the group

were committed to successful completion of the

task. Burke (1969), for example, had stimulated a high legitimation condition by informing his subjects that they must achieve consensus in discussing a human relations case

1 A full debriefingtook place at the end of each

session in which the manipulations and design

were fully explained and questions answered. No

participantsappeared bothered by these manipulations. As will be seen in the next section, the actual

level of hostility initiated by the leader (including

disagreements) was quite low.

and Leadership

/ 483

study. In order to further raise the level of task

motivation, members were informed that the

quality of their discussion would be judged and

rated. After an initial discussion, group members were told that their discussion rated below

the average performance of similar groups, and

that they should perhaps try a little harder.

Groups which had been given no special motivational instructions were found to have a low

level of legitimation of task activity. Therefore,

in order to minimize the degree of commitment

to the groups' task pertinent to the present research and thus minimize the legitimation of

high levels of task-oriented activity, all groups

were told that they had complete freedom in

their task. No conditions other than the task

itself were imposed.

Measur-es

The measures of task and social-emotional

leadership were identical to those previously

used by Burke (1967). Briefly, the subjects

were asked to fill out a questionnaire after the

thirty-minute discussion. Included were eight

questions on which the subjects rated themselves and each other. Four questions were

designed to tap task performance; the other

four, social-emotional performance. These ratings were averaged for each person and standardized within groups to a mean of zero. The

scores were then factor analyzed, and factor

scores were generated for each member on

each of the two dimensions. The group member with the highest score on the task dimension was designated as task leader. Similarly,

the highest-scoring member on the social-emotional dimension was designated social-emotional leader. Table 1 reports the results of the

factor analysis.

For each of the two experimental conditions,

the groups were divided into two types: those

in which the task leader had a task factor score

above the median score of all task leaders (and

therefore more likely to be illegitimately high)

and those in which the task factor score was

below the median performance of task leaders

(and therefore more likely to be seen as

legitimate).

All groups were scored live by two independent observers using Bales' Interaction

Process Analysis. One was the first author who

was, of course, familiar with the hypotheses

484 / SOCIALFORCES/ vol. 52, june 1974

Table 1. Factor Analysis of Eight Role

Performance Items

Task

Dimension

1. Provide fuel for discussion

2. Guide the discussion

3. Attempt to influence the

group's opinion

4. Stand out as leader of the

d iscussion

5. Act to keep relations cordial and friendly

6. Attempt to harmonize differences of opinion

7. Intervene to smooth over

disagreements

8. Make tactful comments

and heal any hurt feelings

.93

.92

.92

SocialEmotional

Dimension

Table 2. Mean Level of Hostility/Support

Toward the

Low-Status Member by Experimental Condition and

Level of Task Leader's Activity

Task Activity

of the

Task Leader

Experimental

Positive

.23

.29

High

1.40

.16

Low

1.60

.95

.24

.07

.85

.44

.78

.28

.86

.18

.80

to be tested. The other scorer operated with no

knowledge of these hypotheses. The measures

of hostility used here and based on the IPA

scores represent an average of the scorer ratings. Following Burke, the main measure of

hostility/support is defined as the sum of the

acts in Category 1 (shows solidarity) and

Category 3 (agrees) minus the sum of acts in

Category 10 (disagrees) and Category 12

(shows antagonism). The more negative the

index, the greater the net level of hostility. By

varying the source and target of the activities,

various specific measures of hostility/support

may be computed-for example, by all members toward the low-status member or by any

one member toward another.

Because the scores using the IPA system

represent an arithmetic mean of the two independent scorers, it is necessary to consider the

reliability between scorers. A reliability coefficient was computed as follows: a withinscorer error variance, VWt,,and a total error

variance, Vt, were calculated, and the reliability

coefficient, r', was computed as I

The reliability of the index of hostility/support

toward the low-status member by all others

across all groups was .88. The reliability between scorers for the index of hostility/support

toward the task leader was .82. In addition, a

reliability coefficient for the index of hostility/

support toward each member was calculated

for each group. The mean coefficient for these

was .90.

Condition

Negative

-1.64

.25

Difference

2.04*

1.35

* p < .10

Before proceeding to analysis of the data,

the establishment of the experimental conditions had to be verified. As it turned out in the

present experiment, the confederate leader

failed to achieve the task leadership position

(i.e., have the highest task factor score) in 4

of the 25 groups; hence these 4 (2 in the positive and 2 in the negative condition) were

eliminated from the analysis. To achieve the

main experimental manipulation, the confederate had been instructed to direct hostility to

the low-status member in the negative condition but to support him in the positive condition. For the 21 groups analyzed, the mean

hostility/support of the confederate toward the

low-status member in the negative condition

was -.82; in the positive condition, +2.25.

The difference between the two, though small,

was significant at the 1 percent level, and represents about 40 percent of the average number

of all positive and negative acts directed by the

task leader to the low-status member.

RESULTS

For both conditions the average level of hostility/support shown toward the low-status

member by group members other than the task

leader is shown in Table 2. These results indicate, in conformity with our first hypothesis,

that the low-status member receives more hostility in the negative support condition when

the leader is highly active in his task performance (t = 1.48, p < .10). The difference between the two conditions is not significant when

the leader is less active; hence the hypothesized

interaction effect is apparently occurring,

though it is not exceptionally strong with this

small sample.

The second hypothesis, which suggests that

the social-emotional leader and the scapegoat

are alternative role responses to the problem

Scapegoating

Table 3. Mean Level of Social-Emotional Activity of

the Social-Emotional Leader by Experimental

Condition and Level of Task Leader's Activity

Task Activity

of the

Task Leader

Experimental

Positive

Condition

Negative

High

1.45

1.36

Low

1.11

1.17

Difference

.09

-.06

of hostility and tension, is tested with the data

in Table 3 showing the mean performance level

of the social-emotional leader in all situations.

These results, though in a direction consistent

with the hypothesis, are not significant.

The third hypothesis suggests a negative correlation between the amount of hostility directed toward the low-status member, by group

members other than the task leader, and the

amount of hostility directed toward the task

leader when the task leader is highly active

and somewhat hostile toward the low-status

member. Table 4 presents the correlations in

all situations. The hypothesis is supported, although again not strongly with the present

small sample (r = .37, p < .10).

The fourth hypothesis suggests a negative

correlation between the amount of hostility

directed toward the task leader and the amount

of social-emotional activity by the social-emotional leader when the task leader is highly

active and somewhat supportive of the lowstatus member. Table 5 presents the correlations for all situations. The hypothesis is not

supported (r- +18, p = ns). Interestingly,

however, the only significant correlation between these two variables is negative, and it

occurs under the negative support condition

with high task-leader activity (r = -.44,

p < .05)-the same situation under which hosTable 4. Correlation Between Amount of Hostility/

Support Directed Toward the Low-Status Member and

the Amount of Hostility/Support

Directed Toward the

Task Leader by Experimental Condition and Level of

Task Leader's Activity

Task Activity of the

Task Leader

High

Positive

-.01

Low

*p

Experimental

.02

<.10

Condition

Negative

37*

-.04

and Leadership

/ 485

Table 5. Correlation Between the Amount of SocialEmotional Activity of the Social-Emotional Leader and

Directed Toward the

the Amount of Hostility/Support

Task Leader by Experimental Condition and Level of

Task Leader's Activity

Task Activity of the

Task Leader

Experimental

Condition

Positive

Negative

High

.18

-.44*

Low

.13

-.02

*p

<.05

tility toward the low-status member seems to

drain hostility away from the task leader. This

finding suggests that both the social-emotional

leader and the scapegoat drain hostility, but,

at least in terms of this research, under the

same rather than different activity and support

situations.

DISCUSSION

We have hypothesized that the task leader provides the cue which stimulates either one of

two tension-draining processes. (1) By being

somewhat hostile toward the low-status member, the task leader was presumed to stimulate

scapegoating because his actions cued the group

members in that direction, opening the channel

for hostility transference. (2) If the task leader

is somewhat supportive of the low-status member, the channel for scapegoating is not opened

and a social-emotional leader will presumably

arise (given at least one group member able

to play that role). The problem here is that,

although we find some support for the idea

that the task leader can stimulate scapegoating

(Hypotheses 1 and 3), we have no evidence

that his supportive actions toward the low-status

member encourages the rise of a social-emotional leader (Hypotheses 2 and 4).

The immediate question, therefore, is why

didn't a social-emotional leader emerge in the

positive condition of support to drain tension

and hostility?

Two general explanations are possible: Either

the hypothesized mechanism of the "theory"

(i.e., the task leader's support level) is not

correct, or the experimental conditions were

not what they were intended to be. When

examining the first alternative, we considered

at least three specific possibilities. First, it

486

/ SOCIAL FORCES / vol. 52, june 1974

might be that the task leader does not provide

a cue for channeling hostility to the low-status

member. However, the fact that scapegoating

occurred under the predicted condition disproved this possibility.

Second, the task leader may have provided

the proper cue to close the channel for scapegoating in the positive condition, but there was

no group member capable of playing the role

of social-emotional leader to the extent that

was necessary. However, this argument may be

countered by noting that subjects were randomly assigned to their groups, and there is

evidence that activity by a social-emotional

leader, as well as scapegoating, served to drain

hostility under the negative support condition.

It is quite unlikely that chance would fail to

assign such individuals to groups opposed to

the positive condition of support.

Third, under the positive support condition

the group members might have been able to

interact without draining the hostility built up

by the task leader's activity. If this explanation

is adequate, we would expect that, in general,

group members experiencing the positive condition would be less satisfied with their experience in the group. To test this idea we examined the responses of group members to two

items on the post-session questionnaire. The

first question asked whether the group members

were more or less tense than they expected

to be; the second asked whether they enjoyed

the experience more or less than they had

expected they would. The subjects' responses

indicated no significant differences between

conditions on either question, and we must

therefore reject this possible explanation.

The second general explanation postulated

error in the experimental conditions. One possibility which was examined was that the low

degree of legitimation necessary for the development of either social-emotional leadership

or scapegoating was not fulfilled. Several approaches to this idea were tested.

First, Burke (1967; 1968) showed that the

separation of the task and social-emotional

leadership roles is much more likely to occur

in conditions of low task legitimation; in conditions of relatively high task legitimation, one

person is quite likely to hold both roles. In our

negative support condition, we found a separation of roles. However, in the positive condi-

tion, in 6 of 10 cases, the task leader and the

social-emotional leader were the same personthe confederate.

Additional comparisons with Burke's (1967)

study lend further support to the possibility

that there was a failure to achieve or maintain

the low degree of task legitimation necessary

for a full test of the hypotheses. For example,

Burke reported a correlation of +.79 between

perceived task performance of the leader and

role differentiation in the low legitimation condition, while the same correlation in the high

legitimation condition was near zero. In this

study we found the same correlations to be

+.63 in the negative support condition but

near zero in the positive condition. Again,

Burke found a correlation of -.43 between

perceived task performance of the leader and

liking of the leader in the low legitimation

condition (ours was -.48 in the negative condition) and near zero in the high legitimation

condition (ours was +.53 in the positive condition). Finally, Burke found a negative correlation between the task leader's task and

in the low

social-emotional scores (-.74)

legitimation condition (ours was -.60 in the

negative condition) but a near zero correlation

(-.14) between these two variables in the high

legitimation condition (ours was +.27 in the

positive condition).

In sum, then, it appears that the general

condition of low legitimation of task activity

intended for both positive and negative conditions of support did not occur in the positive

condition. Thus, while the data show some

evidence that the task leader can instigate

scapegoating by opening a channel of hostility

toward the low-status member, we did not

establish the conditions necessary to test his

ability to instigate social-emotional leadership

by closing the channel of hostility toward the

low-status member. We must now ask why the

groups failed, to achieve low task legitimation

in the positive condition of support.

The concept of legitimation was initially introduced into the theory of role differentiation

by Verba (1961) in two related formats. The

first centered on the degree of acceptability

within a group of instrumental, task-oriented

behavior, while the second focused upon the

acceptability of a particular person (the

"leader") performing instrumental, task-oriented

Scapegoating and Leadership / 487

behavior. In the process of incorporating legitimation into the model of scapegoating (and

role differentiation in general), the theoretical

focus has been on the role of the task leader.

However, experimental attempts to stimulate

a given level of legitimation have frequently

concentrated on the degree of acceptability to

a group, of task-oriented behavior.

In this study the initial task conditions were

held constant in a configuration that, in past

studies, had yielded low legitimation for taskoriented activity. We can thus conclude that

non-task factors were involved in altering the

level of legitimation in the positive support

condition. Two possible factors were the following. First, the confederate may have

achieved a higher level of legitimation for his

own activity in the positive condition by being

generally more supportive of other group members (perhaps by generalizing his instructions

to be supportive of the low-status member).

Second, the confederate may have increased

his level of legitimation in the positive support

condition simply by being supportive toward

the low-status member.

The first possibility does not seem to hold

since we found no significant difference between conditions in support for the group members (t - .94, p = ns). However, the data lend

credence to the second possibility. In the positive support condition we found that the correlation between liking the task leader and the

task leader's support for the low-status member

was +.51 (p < .05). In the negative condition

the same correlation is slightly negative but

not significantly different from zero (-.11,

p = ns). It is possible, therefore, that the confederate leader received additional liking and

legitimation for his task activity because he

supported the low-status member, and this

additional legitimation may have been enough

to invalidate the desired experimental conditions. Further research, in which the confederate is instructed to be neutral toward all members of the group-including

the low-status

member-is needed.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

This article asks how small discussion groups

"choose" between the alternative structures of

scapegoating and social-emotional leadership.

It was hypothesized that the particular mecha-

nism determining which alternative was selected

by the group was whether the task leader supported the low-status member. The experiment

designed to test this mechanism used a confederate leader who acted either in a somewhat

hostile fashion (negative condition) or a supportive fashion (positive condition) toward the

person who ranked lowest in participation (lowstatus member) after the first ten minutes of

discussion. Analysis indicated that scapegoating

of the low-status member occurred in the negative condition more than in the positive (Hypothesis 1 ); and this structure does seem to

draw some hostility away from the leader

(Hypothesis 3). The emergence of a strong

social-emotional leader, however, did not occur

more frequently in the positive condition as

would be suggested by Hypothesis 2. The reason for this lack (suggested by ex post facto

analysis) seems to be that the assumed low

level of legitimation for the task leader's task

activity was, in fact, not there. Further analysis

suggested that, by supporting the low-status

member, the confederate leader raised his own

level of legitimation for performing task activity. In the words of Hollander (1958), he

established sufficient idiosyncracy credit that

his task behavior apparently did not produce

tension and hostility. Without these motivating

factors, neither social-emotional leadership nor

scapegoating, followed. Instead there was a

high degree of what Lewis (1972) calls role

of both task and

integration-performance

social-emotional leadership roles by one person.

We are left, then, with the implication that

the hypothesized mechanism governing the

emergence of scapegoating or social-emotional

leadership must be modified. Hostility of the

group's task leader toward its low-status member produces scapegoating. Task leader support

of the low-status member seems to legitimate

the activity of the task leader rather than necessitate role differentiation in the form of a

separate social-emotional leader. Perhaps neutrality toward the low-status member by the

task leader would produce role differentiation,

and this possibility should be investigated. In

any event, it is clear that the task leader's

behavior toward the low-status member is an

important determinant of the structure of relations in a small discussion group.

488

/ SOCIAL FORCES / vol. 52, june 1974

REFERENCES

Bales, R. F. 1953. "The Equilibrium Problem in

Small Groups." In Talcott Parsons et al. (eds.),

Working Papers in the Theory of Action. New

York: Free Press.

Bales, R. F., and P. E. Slater. 1955. "Role Differentiation in Small Decision-Making Groups." In

Talcott Parsons and Robert F. Bales (eds.),

Family, Socialization

anld Interaction

Process.

Glencoe: Free Press.

Burke, P. J. 1967. "The Development of Task and

Social-Emotional Role Differentiation."Socionietry 30(December):379-92.

. 1968. "Role Differentiation and the Legitimation of Task Activity." Sociometry 31 (December): 404-1 1.

. 1969. "Scapegoating: An Alternative to

Role Differentiation." Sociometry 32(June):

159-68.

Hollander, E. P. 1958. "Conformity, Status and

Review! 65

Idiosyncracy Credit." Psychlological

(March): 117-27.

Lewis, G. H. 1972. "Role Differentiation." A,?ericant Sociological Reviewv 37(August):424-34.

Verba, Sidney. 1961. Small Grolups and Political

Behavior. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Social Class, Style of Life and

Fertility in Puerto Rico*

JOHN C. BELCHER,

KELLY W. CRADER,

University of Georgia

University of Georgia

ABSTRA CT

This study examines the relationship between fertility, social class, and styles of life in Puerto Rico.

Styles of life are viewed as behavioral constellations selected among available cultural alternatives and

manifested in the manner in which goods are consumed. The survey instrument included 43 different

behavoral items believed to reflect viable cultural alternatives. Using a principal components solution

and varimax rotation procedures, the first four factors were initially selected to characterize life-style

components. Cross-tabulations were made on completed fertility by employing both Hollingshead's

Social Classes and the Style of Life typology. The style of life approach systematically differentiates

fertility patterns within what the Hollingshead procedure would indicate to be a homogeneous group.

Studies demonstrating a relationship between

social structure and human fertility (Blau and

Duncan, 1967; Davis and Blake, 1956; Freedman, 1961) have frequently singled out social

The authors wish to acknowledge the cooperation of the Puerto Rican Agricultural Experiment

Station, numerous other Puerto Rican agencies,

many individual citizens plus a grant from the

Agricultural Development Council which permitted

the collection of the data used in this study. Special appreciation is extended to Dr. Pablo VazquezCalcerrada of the University of Puerto Rico whose

collaboration made possible the survey from which

these data are derived. A research grant from the

National Institute of Child Care and Human

Development (Grant Number HD 05775) made

the analysis of these data possible.

class as a principal factor contributing to the

fertility differences observed (Goldscheider,

1971; Stycos, 1968). Research tends to be

either intensive investigation of fertility practices within a given social class or statistical

analysis of the relationship between birth rates

and an index of socioeconomic status (Easterlin, 1969; Peterson, 1969).

Freedman's (1961:59) statement is typical

of the conclusions reached from such studies:

"Differences in life styles associated with position in a status hierarchy presumably may influence any of the norms or intermediate variables affecting fertility." While such statements

often assert or assume the existence of distinctive life styles for the various social classes

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Whitewashing Race - Scapegoating CultureDocument38 pagesWhitewashing Race - Scapegoating Cultureites76Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Spitzer Horowitz - CritiqueDocument3 pagesSpitzer Horowitz - Critiqueites76Pas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Spitzer DevianceDocument15 pagesSpitzer Devianceites76Pas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Luce Moral - Panics JournalismDocument17 pagesLuce Moral - Panics Journalismites76Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Lafferty Devils AdvocateDocument22 pagesLafferty Devils Advocateites76Pas encore d'évaluation

- Erich GoodeDocument9 pagesErich Goodeites76Pas encore d'évaluation

- Erikson - Sociology of DevianceDocument8 pagesErikson - Sociology of Devianceites76Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Crime Media Culture 2011 Young 245 58Document14 pagesCrime Media Culture 2011 Young 245 58ites76Pas encore d'évaluation

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- 'Moral Panic' and Moral Language in The MediaDocument21 pages'Moral Panic' and Moral Language in The Mediaites76Pas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Mathematics Grades I-X Approved by BOG 66Document118 pagesMathematics Grades I-X Approved by BOG 66imtiaz ahmadPas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- EE2001 Circuit Analysis - OBTLDocument7 pagesEE2001 Circuit Analysis - OBTLAaron TanPas encore d'évaluation

- DisneyDocument6 pagesDisneyz.kPas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Oral Language, Stance, and Behavior Different Communication SituationsDocument82 pagesOral Language, Stance, and Behavior Different Communication SituationsPRINCESS DOMINIQUE ALBERTOPas encore d'évaluation

- Eet 699 Writing SampleDocument3 pagesEet 699 Writing SampleChoco Waffle0% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- FIRO Element BDocument19 pagesFIRO Element Bnitin21822Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Tanzimul Ummah International Tahfiz School: Time Activities ResourcesDocument6 pagesTanzimul Ummah International Tahfiz School: Time Activities ResourcesKhaled MahmudPas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- CTE Microproject Group 1Document13 pagesCTE Microproject Group 1Amraja DaigavanePas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Unit 2 Pure Mathematics MCQ Answers (2008 - 2015)Document1 pageUnit 2 Pure Mathematics MCQ Answers (2008 - 2015)Kareem AliPas encore d'évaluation

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Solutions Manual For Power System Analysis and Design 5th Edition by Glover PDFDocument15 pagesSolutions Manual For Power System Analysis and Design 5th Edition by Glover PDFFrederick Cas50% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Resume Final Apr 2019Document2 pagesResume Final Apr 2019Matthew LorenzoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Ea 11 Inglés 4° JBGDocument2 pagesEa 11 Inglés 4° JBGChristian Daga QuispePas encore d'évaluation

- Test A NN4 2020-2021Document2 pagesTest A NN4 2020-2021Toska GilliesPas encore d'évaluation

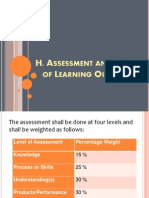

- Assessment and Rating of Learning OutcomesDocument28 pagesAssessment and Rating of Learning OutcomesElisa Siatres Marcelino100% (1)

- What Is Political EconomyDocument10 pagesWhat Is Political EconomyayulatifahPas encore d'évaluation

- Saveetha EngineeringDocument3 pagesSaveetha Engineeringshanjuneo17Pas encore d'évaluation

- Week1module-1 Exemplar Math 7Document5 pagesWeek1module-1 Exemplar Math 7Myka Francisco100% (1)

- DLL Social ScienceDocument15 pagesDLL Social ScienceMark Andris GempisawPas encore d'évaluation

- Department OF Education: Director IVDocument2 pagesDepartment OF Education: Director IVApril Mae ArcayaPas encore d'évaluation

- Folk Tales: Key Learning PointsDocument1 pageFolk Tales: Key Learning PointsIuliana DandaraPas encore d'évaluation

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- IITH Staff Recruitment NF 9 Detailed Advertisement 11-09-2021Document14 pagesIITH Staff Recruitment NF 9 Detailed Advertisement 11-09-2021junglee fellowPas encore d'évaluation

- Demo June 5Document10 pagesDemo June 5Mae Ann Carreon TrapalPas encore d'évaluation

- Personality Development PDFDocument7 pagesPersonality Development PDFAMIN BUHARI ABDUL KHADER80% (5)

- Similarities and Differences of Word Order in English and German LanguagesDocument4 pagesSimilarities and Differences of Word Order in English and German LanguagesCentral Asian StudiesPas encore d'évaluation

- Digital Media SyllabUsDocument1 pageDigital Media SyllabUsWill KurlinkusPas encore d'évaluation

- Lab#7 Lab#8Document2 pagesLab#7 Lab#8F219135 Ahmad ShayanPas encore d'évaluation

- Social Psychology ReflectionDocument3 pagesSocial Psychology Reflectionapi-325740487Pas encore d'évaluation

- International Conservation Project Funders: Institution Award/Scholarship Description Award Amount WebsiteDocument22 pagesInternational Conservation Project Funders: Institution Award/Scholarship Description Award Amount WebsitenicdonatiPas encore d'évaluation

- BarracudasNewsletter Issue1Document8 pagesBarracudasNewsletter Issue1juniperharru8Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ied OIOS Manual v1 6Document246 pagesIed OIOS Manual v1 6cornel.petruPas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)