Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Retro-Molar Trigonal Reconstruction and Oncologic Outcomes After Resection of Large Malignant Ulcers in Elderly Patients

Transféré par

Peertechz Publications Inc.Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Retro-Molar Trigonal Reconstruction and Oncologic Outcomes After Resection of Large Malignant Ulcers in Elderly Patients

Transféré par

Peertechz Publications Inc.Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Archives of Otolaryngology and Rhinology

Sameh Roshdy1, Mohamed T Hafez1,

Islam A El Zahaby1, Osama Hussein1,

Fayez Shahatto1, Mosab Shetiwy1,

Shadi Awny1, Sherif Kotb1, Hend A ElHadaad1 and Adel Denewer2*

Department of Surgical Oncology, Oncology center,

Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University, Egypt

2

Department of Clinical Oncology & Nuclear

Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura

University, Egypt

1

Dates: Received: 09 September, 2015; Accepted:

07 December, 2015; Published: 09 December, 2015

Research Article

Retro-Molar Trigonal

Reconstruction and Oncologic

Outcomes after Resection of Large

Malignant Ulcers in Elderly Patients

*Corresponding author: Professor Adel Denewer,

Head of Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine,

Mansoura University, Egypt, Tel: +201223237791;

E-mail:

Abstract

www.peertechz.com

Aim: The research was designed to study suitability of submental island flap and radial forearm

free flap (RFFF) as one stage reconstructive procedure after resection of large retromolar-trigonal

cancers. And to assess locoregional recurrence and disease free survival after adjuvant treatment.

ISSN: 2455-1759

Keywords: Buccal mucosa cancer; Oral cancers;

Squamous cell cancer of oral mucosa; Submental

Background: Buccal mucosa carcinoma represents 3 to 5% of oral-cavity cancer. Retromolar

buccal trigon affected in one third of patients with buccal mucosal cancers. Squamous cell carcinoma

is the commonest pathological finding.

Methods and techniques: Fifty three patients with retromolar-trigonal cancer underwent

resection with safety margins, cervical block neck dissection and reconstruction with submental island

flap and radial forearm free flap (RFFF) in oncology center Mansoura University from August 2010

to May 2014.

Results: Seven patients underwent RFFF, 46 patients reconstructed with sub-mental flap.

Partial necrosis was encountered in 5 cases of sub-mental flaps but lost flaps were present in 2

cases of RFFF. 14 patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, 33 patients received postoperative

radiotherapy. Local recurrence was 13.2%, 2 year disease free survival (DFS) was 72.7%.

Introduction

Oral cavity cancer globally, wings between the sixth to the eighth

most common malignancy; it comprises more than 30% of all head

and neck cancers [1-3,4]. In Egypt about 4.500 people are diagnosed

with oral cancer every year [5]. Retromolar trigon (RMT) is the buccal

region near the lower third molar tooth that has affected in 15% of all

oral cancers [6-8]. Resection of RMT cancer with 1cm safety margins

all round results in large oral defect. Small defects can be left to heal

by secondary intention or are repaired by primary closure, buccal

advancement flap, palatal pedicled flap, split-thickness skin grafting

or tongue flap [9,10]. Reconstruction of larger retro-molar defects

using pedicled buccal pad of fat flap is frequently insufficient and may

be oncologically unsafe when the tumor is abutting or infiltrating the

buccal pad of fat [11-15]. Pedicled and free myocutaneous flaps albeit

safe and robust, are not suitable options due to additional, unnecessary

muscle bulk. The pectoralis major myocutaneous flap carries about

15% flap related complications with the disadvantages of being

bulky, the need of a second stage for pedicle division, unacceptable

donor site scar in females [16,17]. Thus, RMT defects too wide to be

covered with local flaps and are best served with regional or distant

fasciocutaneous flap reconstruction. Defects of such size are typically

covered with a free fasciocutaneous flap; the most commonly used of

which are the radial forearm flaps (RFFF). The research was designed

to test the safety and efficacy of submental island flap as one stage

reconstructive procedure for large post-surgical RMT oral defects.

We evaluated this technique in comparison with the RFFF as an

accepted standard of care for similar cases.

Patients and Methods

This is a retrospective evaluation of prospectively collected

patients data that was carried out from August 2010 to May 2014 for

patients with buccal mucosal cancer originating in or extending to the

RMT region and presenting to our clinic in Mansoura University Can

cer Center in Egypt (Figure 1). We enrolled all cases with predicted

post-resectional defects 4cm in greatest dimension. Pure soft tissue

resection and marginal mandibular resections were included in the

study. Patients with metastatic disease, poor performance, fully

thickness bony defects necessitating mandibular reconstruction and

Figure 1: Preoperative photo of a large ulcerating SCC in the retromolartrigone

(arrow).

Citation: Roshdy S, Hafez MT, El Zahaby IA, Hussein O, Shahatto F, et al. (2015) Retro-Molar Trigonal Reconstruction and Oncologic Outcomes after

Resection of Large Malignant Ulcers in Elderly Patients. Arch Otolaryngol Rhinol 1(2): 052-056. DOI: 10.17352/2455-1759.000010

052

Roshdy, et al. (2015)

patients who are salvaged by surgery after concurrent chemotherapy

and/or radiotherapy were excluded from this study. All clinical

procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the

ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University,

and after obtaining the written informed consent of the patients.

All patients were evaluated preoperatively by medical history,

physical examination, CT scans and/or MRI from the skull base to the

clavicle and biopsy from the primary lesion. Panorex films were done

when mandibular infiltration was suspected. Patients with tumors

extended to anterior tonsillar pillar or reached the adjacent part of

the tongue base required neoadjuvant chemotherapy that consisted of

cisplatin (60-100 mg/m2/day) on day 1 and 5-FU (1000 mg/m2/day)

on days 1-4 for 3 cycles 21days interval between cycles.

Surgical procedure involves wide local excision of the RMT cancer

including underlying buccinator muscle trans-orally with or without

lip split and sent for frozen section to ensure adequate safety margins

(more than 5mm) (Figure 2). When evident mandibular invasion was

encountered, marginal mandibulectomy was carried out to achieve

clear safety margins. Prophylactic tracheostomy was needed when

there was airway compromise especially in cases extending to anterior

tonsillar pillar and/or the tongue base.

Ipsilateral selective neck dissection (Level I-IV) was done for

clinically node positive cases or radically for large, high grade and

deeply infiltrative tumors. In cases where the base of the tongue is

infiltrated or when the patient presents clinically with bilateral nodal

disease, ipsilateral modified radical neck dissection is done and

contralateral selective node dissection was done. Modified block neck

dissection was indicated if matted lymph nodes or extensive cervical

lymph nodes involvement is found preoperatively and if level IV

nodes are positive on frozen section.

The resulting large surgical defect was reconstructed by submental

island flap or radial forearm free flap (RFFF) (Figures 3a,3b). Choice

of either reconstructive procedure was based on elderly age, or

associated co-morbidities as diabetes mellitus and ischemic heart

diseases and constrictive lung conditions that contraindicate RFFF

reconstruction.

All patients were managed in the ICU for one or two days,

for assuring safety of the airway and vital data, before transfer to

the surgical ward. They received intra-operative antibiotics with

induction of anaesthesia continued for 7 days thereafter. Tube feeding

was used for 5 days before resumption of oral feeding. All our patients

were referred to Clinical Oncology and Nuclear medicine department

for adjuvant therapy recommendations.

Adjuvant therapy

Postoperative radiotherapy: External beam radiotherapy was

used in patients with pathologically nodal positive disease (more

than one lymph node, extra capsular infiltration), T3and T4a; 60Gy

in 30 fractions was given to the primary site and bilateral neck lymph

nodes, single fraction /day /5 settings /week using linear accelerator

6mev photon, 2 parallel opposed field. Spinal cord excluded after

45Gy.

The patients were followed monthly in the first 6 months,

053

Figure 2: Shows the post-resection defect (blue arrow) and the harvested

submental island flap (red arrow).

Figure 3a: Submental flap inset at the defect after passing through a tunnel in

the vestibule of the oral cavity (arrow).

Figure 3b: Radial forarm free flap inset at retromolartrigone defect after

resection of a large SCC (green arrow) with completed arterial anastomosis

(red arrow) and venous anastomosis (blue arrow).

then 3 months in the first 2 years then every six months thereafter.

During follow up visit, patients were examined clinically and by neck

US. Biopsy from suspected lesion was taken for histopathological

examination. Cosmesis and oral functions regarding speech,

swallowing and occlusion were assessed in every visit. CT or MRI

neck every 3 month (Figures 4a,4b).

Statistics

Descriptive data are presented as number and percentages.

Functional outcome of submental flap versus RFFF was compared

using Fisher exact test.

Results

Fifty-three eligible patients were enrolled in the study. Mean age

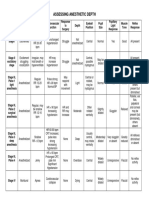

of patients was 57 (7.15) years. Table 1 shows patients characteristics

and tumors description. Out of 53 patients, four had histologically

positive margins by frozen section and subjected to re-excision.

Marginal mandibulectomy was needed in two patients due to evident

cortical infiltration. Nine cases showed extension to anterior tonsillar

Citation: Roshdy S, Hafez MT, El Zahaby IA, Hussein O, Shahatto F, et al. (2015) Retro-Molar Trigonal Reconstruction and Oncologic Outcomes after

Resection of Large Malignant Ulcers in Elderly Patients. Arch Otolaryngol Rhinol 1(2): 052-056. DOI: 10.17352/2455-1759.000010

Roshdy, et al. (2015)

the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap are often bulky with difficult

inset in this posteriorly located defect [16-19].

Figure 4a: Four months postoperative view of a submental island flap

reconstruction of a retromolartrigone defect (arrow).

Figure 4b: Fourteen Months postoperative view of a radial forarm free flap

reconstruction of a retromolartrigone defect (arrow).

pillar and three cases reached the adjacent part of the tongue base and

required excision.

Selective neck dissection (level I-IV) was done for 47 patients;

however modified radical neck dissection was needed in six patients

with clinically overt neck disease. The size of the post resection defect

varied from 4x4 to 5x6 cm. Reconstruction of the resulting defects was

carried out by submental island flap in 46 patients and with RFFF in

seven cases. All patients had smooth hospital stay and postoperative

course except for 5 cases with submental island flap reconstruction

had partial flap necrosis resulting in minor salivary leak which was

managed conservatively. Two out of 7 cases reconstructed by RFFF

suffered complete flap loss with subsequent major salivary leak and

those patient required re-surgery and were backed-up by pectoralis

major myocutaneous flap. Table 2 shows operative data and flap

related complications, cosmetic and functional outcome. Locoregional recurrence was detected in 7 cases (13.2) % during the first

year of the follow up, 5 cases after submental flap reconstruction

and 2 after RFFF. These lesions were large enough that mandate reexcision and postoperative radiotherapy. Fourteen patients received

neoadjuvant chemotherapy, 33 patients received postoperative

radiotherapy. The 2-year disease free survival among patients received

postoperative radiotherapy was 72.7% (Figure 5).

Discussion

The decision making regarding the reconstructive approach after

oral cancer extirpation, especially the retro-molar trigone, remains

a clinical dilemma, which is complicated by the enormous array of

procedures suitable for a given defect, each one offering pros and

cons.

However, when dealing with a large retro-molar trigonal defects

there is limited reconstructive options as nearby local mucosal or

palatal flaps that are usually insufficient, and could result in large

denuded areas [9,10], and other pedicled regional or distant flaps as

054

The commonly used reconstructive procedure for those large

retro-molar trigone defects are the microvascular free flaps especially

the radial forearm free flap which becomes the state of the art

reconstructive method for almost all oral defects being thin, pliable,

wide caliber and long vascular pedicle [20-23], nevertheless, this

Table 1:

patients).

Patients

characteristics

and

Tumor

description"

Characteristics

No.(%)

Gender

Males

Females

40(75.5)

13(24.5)

Associated comorbidities

Diabetes mellitus

Ischemic heart disease

Chronic obstructive chest disease

Chronic compensated liver disease

34 (64)

10 (18.8)

2 (3.8)

13 (24.5)

Tumor pathology

G1-2 SCC

G3 SCC

48(90.6)

5 (9.4)

Primary tumor site

- RMT

- Buccal mucosa extending to RMT.

33(62.3)

20(37.7)

Defect anatomy

Vestibular mucosa only

Tonsillar pillar

Tongue base

Mandibular periosteum

Mandibular cortex

37 (68.8)

9 (16.9)

3 (5.6)

2 (3.7)

2 (3.7)

T stage (AJCC)

T2

T3

T4a

31(58.5)

20(37.7)

2(3.8)

cN stage (AJCC)

N0

N1

N2a

N2b

9 (17)

25(47.2)

13(24.5)

6(11.3)

Neo-adjuvant chemotherapy

14 (26.4)

Postoperative radiotherapy

33 (62.3)

Loco regional recurrence

7(13.2)

(N=53

AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual.

Table 2: Operative details,flap-related complications, Cosmesis and functional

outcomes".

Type of reconstruction

Submental island

P value (Fisher

RFFF (N=7)

flap (N=46)

test)

Operative details

Flap harvest time in min 45+ 10

Surgical teams

Single

90+ 20

Two

Flap necrosis

Partial 015

Complete

5

0

0

2

P=NS

P=0.015

Salivary leak

P=NS

Cosmesis

Good

Excellent

Oral function

Mouth occlusion

Mastication

Swallowing

Satisfactory

Not disturbed

Easy

Satisfactory

Not disturbed

Easy

Citation: Roshdy S, Hafez MT, El Zahaby IA, Hussein O, Shahatto F, et al. (2015) Retro-Molar Trigonal Reconstruction and Oncologic Outcomes after

Resection of Large Malignant Ulcers in Elderly Patients. Arch Otolaryngol Rhinol 1(2): 052-056. DOI: 10.17352/2455-1759.000010

Roshdy, et al. (2015)

In the present study the 2-year DFS was 72.2 and this result is

similar to that of Ghoshal et al. [32], who reported 2-year DFS in

radically treated patients 76.4%.

Conclusion

Judicious use of submental island flap offers an easy way to

reconstruct large intra-oral defects. We believe thatfree flaps in head

and neck reconstruction are an ideal procedure but need advanced

surgical skills and not suitable for most of our patients in Oncology

Center- Mansoura University, and we suggest that the submental

flap should be present in the reconstructive surgeon armamentarium

when dealing with large retro-molar trigonal defect.

References

1. Jemal AR, Siegel E, Ward T, Murray JQ, Xu C, et al. (2006) Cancer statistics.

CA Cancer J Clin 56: 106-130.

Figure 5: Disease Free Survival among cases received post-operative RT.

microvascular techniques require good patient performance, expertise

and facilities. Therefore, not all patients or centers are candidate for

this sophisticated and lengthy micro-surgical techniques.

The submental island flap had emerged as a simple, secure,

easy, versatile reconstructive technique for those large retro-molar

trigonal defects and other oral and perioral defects with comparable

oncological and functional outcome [24-27]. In addition to, anterior

belly of digastric muscle taken within flap ensures closing of

dead space and gives support to cheek especially after resection of

buccinator muscle. Postoperative radiotherapy has no effect on flap

viability or its texture. Removing excess submental skin redundancy

with primary closure of donor site gives cosmetic improvement. In

our study we found no cases of complete submental island flap loss

even in elderly patients with associated co-morbidities, so it is suitable

for nearly all cases of the study. On the contrary, radial forearm free

flap was selected only for those fit patients, required longer operative

time, prolonged hospital stay, continued anticoagulant therapy for at

least 6 months and showed higher rate of total flap loss and donor site

morbidities.

The only disadvantage of the submental island flap is hair bearing

inside oral cavity in male patients and might be the proposed concept

of its interference with sound oncologic neck dissection.

As regard lymphadenectomy, proper neck node staging is done

for all the cases by resecting at least ten lymph nodes in positive cases

to achieve accurate pN stage [28].

But there is still controversy about interference of SMIF harvesting

with sound oncologic lymph node dissection [29].

In our study the local recurrence reported in 13.2% of our

patients. Coppen et al. [30], reported 25% a local relapse, Diaz et al.

[31], reported an overall recurrence rate of 45% (54/119) and a local

recurrence rate of 32% (38/119). Ghoshal et al. [32], documented a

2% regional recurrence rate while Bachar et al. [33], reported that

regional recurrence occurred in six patients and local and regional

recurrence in four patients (70 patients included in this study) also

Hakeem et al. [34], reported a local recurrence in (9.6%).

055

2. Mignogna MDS, Fedele L, Lo Russo (2004) The World Cancer Report and

the burden of oral cancer. European Journal of Cancer Prevention 13: 139142.

3. Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P (2005) Global cancer statistics 2002.

CA Cancer J Clin 55: 74-108.

4. Mehanna H, Paleri V, West CM, Nutting C (2011) Head and neck cancer-Part

1: Epidemiology, presentation, and preservation. Clin Otolaryngol 36: 65-68.

5. El-Mofty S, (2010) Early detection of oral cancer. Egypt J Oral Maxillofac Surg

1: 25-31.

6. Wood WC, Moore S, Staley C, Skandalakis JE (2010) Anatomic Basis of

Tumor Surgery: Springer.

7. Moore MA, Ariyaratne Y, Badar F, Bhurgri Y, Datta K, et al. (2010) Cancer

Epidemiology in South Asia - Past, Present and Future. Asian Pac J Cancer

Prev 11: 49-66.

8. Bhurgri Y (2005) Cancer of the oral cavity - trends in Karachi South (19952002). Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 6: 22-26.

9. Guven O, (1998) A clinical study on oroantral fistulae. J Craniomaxillofac

Surg 26: 267-271.

10. el-Hakim IE, el-Fakharany AM (1999) The use of the pedicled buccal fat pad

(BFP) and palatal rotating flaps in closure of oroantral communication and

palatal defects. J Laryngol Otol 113: 834-838.

11. Zhang HM, Yan YP, Qi KM, Wang JQ, Liu ZF (2002) Anatomical structure of

the buccal fat pad and its clinical adaptations. Plast Reconstr Surg 109: 25192520.

12. Mohan S, Kankariya H, Harjani B (2012) The use of the buccal fat pad for

reconstruction of oral defects: review of the literature and report of cases. J

Maxillofac Oral Surg 11: 128-131.

13. Hazrati EF, Loh, H Loh (1992) Use of the buccal fat pad for correction of

intraoral defects. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 90: 151.

14. Bither SR, Halli, Kini Y (2013) Buccal fat pad in intraoral defect reconstruction.

Journal of maxillofacial and oral surgery 12: 451-455.

15. Hao SP (2000) Reconstruction of oral defects with the pedicled buccal fat pad

flap. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery: 863-867.

16. Mehta S, Sarkar S, Kavarana N, Bhathena H, Mehta A (1996) Complications

of the Pectoralis Major Myocutaneous Flap in the Oral Cavity: A Prospective

Evaluation of 220 Cases. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 98: 31-37.

17. Hsing CY, Wong YK, Wang CP, Wang CC, Jiang RS, et al. (2011) Comparison

between free flap and pectoralis major pedicled flap for reconstruction in oral

cavity cancer patients A quality of life analysis. Oral Oncology 47: 522-527.

18. Liu HL, Chan JYW, Wei WI (2010) The changing role of pectoralis major

Citation: Roshdy S, Hafez MT, El Zahaby IA, Hussein O, Shahatto F, et al. (2015) Retro-Molar Trigonal Reconstruction and Oncologic Outcomes after

Resection of Large Malignant Ulcers in Elderly Patients. Arch Otolaryngol Rhinol 1(2): 052-056. DOI: 10.17352/2455-1759.000010

Roshdy, et al. (2015)

flap in head and neck reconstruction. European Archives of Oto-RhinoLaryngology 267: 1759-1763.

19. Shah JP, Haribhakti V, Loree TR, Sutaria P (1990) Complications of the

pectoralis major myocutaneous flap in head and neck reconstruction. The

American Journal of Surgery 160: 352-355.

20. Cheng YS, Li WL, Xu L, Xu ZF, Liu FY, et al. (2013) Assessment of quality

of life of oral cancer patients after reconstruction with radial forearm free

flaps. Zhonghua kou qiang yi xue za zhi = Zhonghua kouqiang yixue zazhi =

Chinese journal of stomatology 48:161-164.

21. Shah JP, Gil Z (2009) Current concepts in management of oral cancer-surgery. Oral Oncol 45: 394-401.

22. Eckardt A, Meyer A, Laas U, Hausamen JE (2007) Reconstruction of defects

in the head and neck with free flaps: 20 years experience. British Journal of

Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 45: 11-15.

27. Elzahaby IA, Mohammed OH, Hafez MT, Abd Elaziz SR, Mosbah MM, et al.

(2013) Reconstruction of the lip commissure with upper and lower lip fullthickness defects using submental and nasolabial flaps: a case report. Annals

of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery 13: 27.

28. Edge S, Byrd D, Compton C, Fritz A, Greene F & Trotti A (2010) Lip and

Oral Cavity American Joint Cancer Committee (AJCC) staging Manual, 7th

edition, Springer-Verlag New York 31.

29. Elzahaby IA, Roshdy S, Shahatto F, Hussein O (2015) The adequacy of

lymph node harvest in concomitant neck block dissection and submental

island flap reconstruction for oral squamous cell carcinoma; a case series

from a single Egyptian institution. BMC Oral Health.

30. Coppen C, de Wilde PC, Pop LA, van den Hoogen FJ, Merkx MA (2006)

Treatment results of patients with a squamous cell carcinoma of the buccal

mucosa. Oral Oncology 42: 795-799.

23. Blanchaert RH (2012) Survival after free flap reconstruction in patients with

advanced oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 70: 460.

31. Diaz EM Jr, Holsinger FC, Zuniga ER, Roberts DB, Sorensen DM

(2003) Squamous cell carcinoma of the buccal mucosa: one institutions

experience with 119 previously untreated patients.Head Neck25: 267273.

24. Chen WL, Yang ZH, Huang ZQ, Wang YY, Wang YJ, et al. (2007) [Reverse

facial artery-submental artery island myocutaneous flap for reconstruction

of oral and maxillofacial defects following cancer ablation]. Zhonghua Kou

Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi 42: 629-30.

32. Ghoshal S, Mallick I, Panda N, Sharma SC (2006) Carcinoma of the

buccal mucosa: analysis of clinical presentation, outcome and prognostic

factors.Oral Oncol42:533539.

25. Merten SL, Jiang RP, Caminer D (2002) The submental artery island flap for

head and neck reconstruction. Anz Journal of Surgery 72: 121-124.

33. Bachar G, Goldstein DP, Barker E, Lea J, OSullivan B, et al. (2012)

Squamous cell carcinoma of the buccal mucosa: Outcomes of Treatment in

the modern era. The Laryngoscope 122: 1552-1557.

26. Martin D, Pascal JF, Baudet J, Mondie JM, Farhat JB, et al. (1993) The

submental island flap: a new donor site. Anatomy and clinical applications as

a free or pedicled flap. Plastic and reconstructive surgery 92: 867-873.

34. Hakeem AH, Pradhan SA, Tubachi J, Kannan R (2013) Outcome of per

oral wide excision of T1-2 N0 localized squamous cell cancer of the buccal

mucosa--analysis of 156 cases. Laryngoscope 123: 177-180.

Copyright: 2015 Roshdy S, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

056

Citation: Roshdy S, Hafez MT, El Zahaby IA, Hussein O, Shahatto F, et al. (2015) Retro-Molar Trigonal Reconstruction and Oncologic Outcomes after

Resection of Large Malignant Ulcers in Elderly Patients. Arch Otolaryngol Rhinol 1(2): 052-056. DOI: 10.17352/2455-1759.000010

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Survey of Solid Waste Management in Chennai (A Case Study of Around Koyambedu Market and Madhavaram Poultry Farms)Document4 pagesA Survey of Solid Waste Management in Chennai (A Case Study of Around Koyambedu Market and Madhavaram Poultry Farms)Peertechz Publications Inc.100% (1)

- Angiosarcoma of The Scalp and Face: A Hard To Treat TumorDocument4 pagesAngiosarcoma of The Scalp and Face: A Hard To Treat TumorPeertechz Publications Inc.Pas encore d'évaluation

- MEK Inhibitors in Combination With Immune Checkpoint Inhibition: Should We Be Chasing Colorectal Cancer or The KRAS Mutant CancerDocument2 pagesMEK Inhibitors in Combination With Immune Checkpoint Inhibition: Should We Be Chasing Colorectal Cancer or The KRAS Mutant CancerPeertechz Publications Inc.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Fishing Condition and Fishers Income: The Case of Lake Tana, EthiopiaDocument4 pagesFishing Condition and Fishers Income: The Case of Lake Tana, EthiopiaPeertechz Publications Inc.Pas encore d'évaluation

- PLGF, sFlt-1 and sFlt-1/PlGF Ratio: Promising Markers For Predicting Pre-EclampsiaDocument6 pagesPLGF, sFlt-1 and sFlt-1/PlGF Ratio: Promising Markers For Predicting Pre-EclampsiaPeertechz Publications Inc.Pas encore d'évaluation

- International Journal of Aquaculture and Fishery SciencesDocument4 pagesInternational Journal of Aquaculture and Fishery SciencesPeertechz Publications Inc.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Imaging Journal of Clinical and Medical SciencesDocument7 pagesImaging Journal of Clinical and Medical SciencesPeertechz Publications Inc.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- 7 AHM Antibiotic PolicyDocument98 pages7 AHM Antibiotic PolicyfaisalPas encore d'évaluation

- Data 14-12-2021 Formulir TB TerbaruDocument1 pageData 14-12-2021 Formulir TB TerbaruAksaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating PolyradiculoneuropathyDocument5 pagesChronic Inflammatory Demyelinating PolyradiculoneuropathyDiego Fernando AlegriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Allergic Contact DermatitisDocument12 pagesAllergic Contact DermatitisAzis BoenjaminPas encore d'évaluation

- Disorders of Immunity Hypersensitivity Reactions: Dr. Mehzabin AhmedDocument25 pagesDisorders of Immunity Hypersensitivity Reactions: Dr. Mehzabin AhmedFrances FranciscoPas encore d'évaluation

- Curriculum Vitae: School of Regeneration and Encouragement KEMA FK UNPADDocument7 pagesCurriculum Vitae: School of Regeneration and Encouragement KEMA FK UNPADReki PebiPas encore d'évaluation

- Rachel Bray - ResumeDocument2 pagesRachel Bray - Resumeapi-625221885Pas encore d'évaluation

- Anesthesia-Assessing Depth PDFDocument1 pageAnesthesia-Assessing Depth PDFAvinash Technical ServicePas encore d'évaluation

- Sports DrinksDocument2 pagesSports DrinksMustofaPas encore d'évaluation

- A Silent KillerDocument3 pagesA Silent KillerLinhNguyePas encore d'évaluation

- The GINA 2019 Asthma Treatment Strategy For Adults and Adolescents 12... Download Scientific DiagramDocument1 pageThe GINA 2019 Asthma Treatment Strategy For Adults and Adolescents 12... Download Scientific DiagramFatih AryaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ok - Effect of Melatonin On Broiler ChicksDocument12 pagesOk - Effect of Melatonin On Broiler ChicksOliver TalipPas encore d'évaluation

- COVID-19 and Pregnancy: A Review of Clinical Characteristics, Obstetric Outcomes and Vertical TransmissionDocument20 pagesCOVID-19 and Pregnancy: A Review of Clinical Characteristics, Obstetric Outcomes and Vertical TransmissionDra Sandra VèlezPas encore d'évaluation

- Acute Gastritis CiciDocument43 pagesAcute Gastritis CiciDwi Rezky AmaliaPas encore d'évaluation

- Annotated BibliographyDocument4 pagesAnnotated BibliographyJuanPas encore d'évaluation

- Vitamin and Mineral Supplementation During PregnanDocument4 pagesVitamin and Mineral Supplementation During PregnanEvi RachmawatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Drugs Used in Heart FailureDocument33 pagesDrugs Used in Heart FailureLynx Kee Bayating100% (1)

- Insights and Images: Vascular Channel Mimicking A Skull FractureDocument2 pagesInsights and Images: Vascular Channel Mimicking A Skull Fracturethariq mubarakPas encore d'évaluation

- Secukinumab: First Global ApprovalDocument10 pagesSecukinumab: First Global ApprovalAri KurniawanPas encore d'évaluation

- DKA Handout1Document59 pagesDKA Handout1alePas encore d'évaluation

- He2011 TMJ ANKYLOSIS CLASSIFICATIONDocument8 pagesHe2011 TMJ ANKYLOSIS CLASSIFICATIONPorcupine TreePas encore d'évaluation

- Patient Wellbeing Assessment and Recovery Plan - Children and AdolescentsDocument12 pagesPatient Wellbeing Assessment and Recovery Plan - Children and AdolescentsSyedaPas encore d'évaluation

- National NORCET Test-9Document106 pagesNational NORCET Test-9SHIVANIIPas encore d'évaluation

- Exercise #1 10Document10 pagesExercise #1 10John Paul FloresPas encore d'évaluation

- Medical Symptoms QuestionnaireDocument29 pagesMedical Symptoms QuestionnaireOlesiaPas encore d'évaluation

- NephrologyDocument9 pagesNephrologyEliDavidPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson Plan On Spina BifidaDocument24 pagesLesson Plan On Spina BifidaPriyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gujarat Technological University: W.E.F. AY 2017-18Document3 pagesGujarat Technological University: W.E.F. AY 2017-18raj royelPas encore d'évaluation

- Foundations of Operative Surgery An Introduction To Surgical TechniquesDocument165 pagesFoundations of Operative Surgery An Introduction To Surgical TechniquesTeodora-Valeria TolanPas encore d'évaluation

- Hydatidiform MoleDocument2 pagesHydatidiform MoleIrfan HardiPas encore d'évaluation