Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Analyzing The Intensity of Private Label Competition Across Retailers

Transféré par

Allan AlvesTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Analyzing The Intensity of Private Label Competition Across Retailers

Transféré par

Allan AlvesDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Journal of Business Research 66 (2013) 6066

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Business Research

Analyzing the intensity of private label competition across retailers

John Dawes , Magda Nenycz-Thiel

Ehrenberg-Bass Institute for Marketing Science, University of South Australia, GPO Box 2471 Adelaide SA 5001, Australia

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 1 June 2010

Received in revised form 1 November 2010

Accepted 1 February 2011

Available online 26 August 2011

Keywords:

Private label

Own label

National brand

Competition

Duplication of purchase

Price promotions

a b s t r a c t

Examining how buyers of one private label (PL) in a product category also cross-purchase the private labels of

competing retailers in the same category is the focus of this study. Understanding consumer cross-purchasing of

PLs is important to retailers, who use PLs as one tactic to differentiate from other retailers; and important to

manufacturers, who compete against PLs. A higher level of PL cross-purchasing indicates heightened competitive

intensity among the PLs of rival retailers. Results across 27 categories indicate that PLs compete against national

brands (NBs) within-store, but also compete against the PLs of other retailers across stores. Heightened

competition among the PLs of different retailers occurs in categories with higher purchase frequency; in which

the average PL price is well below the average NB price; and in categories with higher levels of manufacturer

brand price promotions.

2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Companies generally brand their products with a national brand

label or a private label. The owner of a national brand (NB) is generally

a producer. Retailers, wholesalers, or distributors own private-label

(PL) brands, which are also known as home brands, store brands or

own label brands (Bushman, 1993; De Wulf, Odekerken-Schrder,

Goedertier, & Van Ossel, 2005). Manufacturers, whom often also

produce the national brands that the PLs compete against, produce

the PLs. From a marketing mix point of view, the main differences

between the two types of brands are advertising support, distribution

and price. NBs tend to obtain more advertising support at the national

level than do PLs. While retailers who own PLs do advertise

extensively, the advertising support is spread over all the products

in the store, rather than being for the retailer's own specic PL. PLs

tend to have restricted distribution compared to NB's because they

sell in one retail chain (Chen, Narasimhan, & Dhar, 2010). By contrast,

NBs sell in multiple retail chains. While some retailers such as Tesco in

the UK have expanded their retail presence such that the availability

of their PL is arguably comparable to NBs, in general PLs are less

widely available than NBs. Finally, the majority of PLs are cheaper than

NBs. Both brand types appear next to each other on retail shelves and

therefore they compete for consumers choice.

The authors thank three anonymous reviewers whose comments greatly improved

the paper.

Corresponding author. Tel.: + 61 8 8302 0592; fax: + 61 8 83020442.

E-mail addresses: John.Dawes@marketingscience.info (J. Dawes),

Magda.Nenycz-Thiel@MarketingScience.info (M. Nenycz-Thiel).

0148-2963/$ see front matter 2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.023

PL brands have witnessed signicant growth in the past two

decades, far outpacing the growth of NBs (Baltas & Argouslidis, 2007;

Lincoln & Thomassen, 2008). PL growth is particularly strong in Europe

(Euromonitor, 2007). In the UK, the focus of this study, grocery market

share of PLs grew from 39% of sales in 2008 to 41% in 2010 (Marian,

2010). PL share is also growing fast in the US (Loechner, 2010).

Retailers usually carry several tiers of PLs to cover the spectrum of

consumer needs: from value products that compete mostly on price,

to premium products that offer the highest quality and unique lines at

prices equal or higher than NBs (Kumar & Steenkamp, 2007). All PLs

compete against NBs and, given that people shop at different stores,

they compete against the PL brands of other retailers. Therefore,

research into how PLs compete is important for NB managers, but also

managers of PL brands and retailers in general.

In order to understand the full picture of PL competition, the study

examines competition between PLs and NBs within a store, as well as

the competition between the PLs of competing stores. The reason for this

dual focus is that consumers distribute their purchases across different

stores over a time period such as six months or a year (Uncles &

Hammond, 1995). The present study analyzes consumer purchase

records to see how, in a given category, PLs and NBs share consumers

with each other. Specically, the study examines which brands the

buyers of one retailer's PL buy, when they re-purchase from the same

category (either at the same retailer, or at another retailer). The study

examines the extent to which buyers of one retailer's PL switch to NBs if

they visit another store, or stick to PLs at the rival chain. The analysis

uses multiple categories to identify category characteristics that

heighten or lessen the tendency to cross-purchase PL brands.

This study provides important contributions to the marketing

literature. Even though PL competition has been an area of research

J. Dawes, M. Nenycz-Thiel / Journal of Business Research 66 (2013) 6066

for many years, the majority of studies focus on shopper behavior at

just one retail chain. A single-chain focus hampers the ability to detect

the full extent of competition between all NBs and all PLs. The present

study considers shopping behavior across many retail chains, which

allows a fuller picture of competition between PLs and NBs. The

implications from this research are important for marketers of PLs and

NBs. First, retailers stock PLs to create a point of differentiation from

other retailers (Ailawadi, Neslin, & Gedenk, 2001; Corstjens & Lal,

2000) and build customer loyalty. If consumers engage in crossretailer PL buyingbuying the PLs of multiple retailers in the same

category in a time periodthis suggests retailers are less successful in

their differentiation strategy. In addition, identifying NB-PL competitive

market structure will show whether PL brands take their sales primarily

from NBs, or from other PLs. The analysis can therefore clarify the real

threat PLs pose to NB manufacturers in a selected category.

Organization of the paper is as follows. The next section discusses

the literature on PL competition and segmentation. Description of the

data and analysis follows the literature review. Results and discussion

come after the analysis. Implications, limitations and areas for future

research conclude the paper.

61

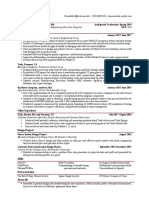

Table 1

Overview of major ndings concerning PL / NB competition.

Main ndings

Source

High price substitutability between NBs

and PLs leads to higher private label

brand shares and retailer prots.

Categories where PLs are most likely to

succeed are those with many NBs, as an

introduction of a PL does not have large

negative impacts on retailer prots from

NBs.

Consumers cross-buy NB's and PL's

approximately in-line with their

respective market shares

PLs compete most effectively when they

target the leading NB.

Raju, Sethuraman, and Dhar (1995),

Morton and Zettelmeyer (2004)

Second tier NBs suffer the most in the

PL / NB competition

PL share is lower in categories with high

NB advertising expenditure

Price cuts on NBs hurt PLs more than PL

price cuts hurt NBs

Raju et al. (1995), Morton and

Zettelmeyer (2004)

Uncles and Ellis (1989), Ellis and

Uncles (1991), Bound and Ehrenberg

(1997)

Sayman, Hoch, and Raju (2002),

Sethuraman and Srinivasan (2002),

Morton and Zettelmeyer (2004),

Pauwels and Srinivasan (2004), Kumar

and Steenkamp (2007)

Hoch and Banerji (1993), Dhar and Hoch

(1997), Morton and Zettelmeyer (2004)

Blattberg and Wisniewski (1989),

Sethuraman (1996), Cotterill and Putsis

(2000)

2. Background

2.1. How do private labels compete?

Consider a consumer in a retailer's store making a purchase. The

consumer can usually choose among a range of NBs and PLs offered by

that specic retailer. Competition within the store is therefore

principally NBs versus PLs. Furthermore, PL brands face restricted

availability. For example, Tesco private label cola is not available in

Sainsbury, but NBs such as Coke and Pepsi are available in almost every

retailerall major chains as well as independents and convenience

stores. Therefore, restricted availability should constrain the tendency of

the PL buyers of one retailer to also buy the PL brands of other retailers.

Indeed, examinations of the competitive environment for PLs generally

focus on the competition between PLs and NBs, not PLs against other PLs

(e.g., Parker & Kim, 1997; Quelch & Harding, 1996; Steiner, 2004).

Table 1 summarizes prominent studies of PL competition.

While PL brands face restricted availability, evidence shows that

shoppers in frequently bought categories shop at multiple stores in a

specied time period (Ellis & Uncles, 1991; Uncles & Ellis, 1989; Uncles &

Hammond, 1995). Therefore, consumers encounter the PLs of different

stores at different times. The result is that consumers buy multiple PL

brands (of various retailers) just as they do for NBs. Three studies

(Bound & Ehrenberg, 1997; Ellis & Uncles, 1991; Uncles & Ellis, 1989)

examined the buying patterns of PL and NB consumers, and found that

PLs share customers with NBs and also with other PLs, approximately

in-line with their respective market shares. However, there are several

reasons why further investigation could enhance the state of knowledge

about PL-NB competition. First, studies such as Bound and Ehrenberg

(1997) reported aggregated results for PL brandssuch aggregation

might mask a tendency for PLs to compete more intensely in some

categories and less so in others. A category-by-category analysis could

therefore reveal specic categories in which PLs compete especially

intensely. Second, PLs have continued to grow and evolve over the past

ten years (Kumar & Steenkamp, 2007), therefore the extent to which

consumers cross-buy various PL labels may have changed. Third, retailer

concentration is now very high in markets such as the UK, with the

ve leading retailers accounting for over 50% of all grocery sales

(Euromonitor, 2007). Higher retail concentration could lead to more

private-label proneness because larger, consolidated retailers can invest

in PLs more than would occur with a fragmented retail sector with many

smaller operators. Finally, the rise of retailer loyalty programs

(Liu, 2007; Meyer-Waarden & Benavent, 2006; Uncles, Dowling, &

Hammond, 2003) could result in more shoppers being private-label

prone because retailers can use those programs to specically promote

their own PLs (Nies & Natter, 2010). The paper now briey discusses

private-label proneness and contextualises research on that topic in

relation to the present study.

2.2. The private-label prone shopper

As the term suggests, a private-label prone shopper buys PL brands

to a greater extent than would be expected given the market share of

those PL brands. Identifying the characteristics of the PL-prone shopper

is one of the oldest research topics in the PL literature, with 26 studies

published between 1965 and 2004 (Sethuraman, 2006). A rationale for

academic interest in this topic is that since PLs tend to be low priced, the

people who buy them comprise a price sensitive segment. As Baltas

(1997, p. 315) states, the most obvious benet to consumers afforded

by own brands is lower prices. Indeed, in the majority of the studies in

this area, consumers who buy PLs exhibit higher price sensitivity (e.g.,

Ailawadi et al., 2001; Baltas, 1997). However, there is also strong

evidence that those who buy PLs are equally quality sensitive (e.g., Batra

& Sinha, 2000). Several studies (Coe, 1971; Fitzell, 1982) posit that low

household income is a likely indicator of PL proneness. However,

empirical results show the counterintuitive oppositethat lower

income customers buy fewer private-label brands. The reason stated

for this result is that consumers with lower income usually have lower

education levels and stronger price-quality associations, leading to

greater trust in national brands and more receptivity to national brand

advertising. Sethuraman and Cole (1999) nd that those with middle

income are most likely to buy PLs. The mixed results about PL

segmentation lead to an opinion in the literature that the direct effect

of demographics and psychographics on PL usage is relatively weak

(Ailawadi et al., 2001; Baltas & Argouslidis, 2007).

The private-label prone shopper concept implies heightened

competition between the PLs of rival retailers. However, the concept

does not distinguish between propensity to buy many private-label

products from the same retailer, versus propensity to buy the PLs of

different retailers in a time period, such as a year. Specic investigation

of shopper propensity to buy the PLs of different retailers will assist in

understanding the broader idea of private-label proneness, as well as PL

competition among retailers.

Therefore, the present study builds on these following points:

Some consumers at least, may be private-label prone;

PL proneness may manifest not only in a heightened tendency to

buy PLs across different categories from one retailer, but to unduly

purchase PLs from any retailer the shopper visits;

62

J. Dawes, M. Nenycz-Thiel / Journal of Business Research 66 (2013) 6066

PL proneness may be more prevalent in certain product categories than

in others, thus there is a need for category-by-category examination.

These points lead to two research questions:

RQ1. Do PL buyers at retailer A have a heightened tendency to also

buy the PL brands of retailers B, C, etc. in a time period such as a year?

RQ2. What category characteristics inuence the intensity of crossretailer PL competition?

3. Method

The method is to analyze the cross-purchasing of PLs and NBs over a

specied time period such as a year. The cross-purchase analysis

identies if buying one PL increases the tendency to buy a different

retailer's PL in the same category. While the focus of the study is PL

brands, the analysis includes NBs as a comparison. The overall approach

is purchase duplication analysis: the extent to which buyers of one

brand also appear as buyers of another brandi.e., are duplicated in the

other brand's customer basein a time period.

Calculated rst is the proportion of consumers who buy a brand in

a time period (i.e., the brand's penetration). Consumers buy multiple

brands in a time period (Ehrenberg & Goodhardt, 1970), therefore a

proportion of the buyers of brand A also buy brand B, C, D and so on.

The proportion of A buyers who also buy brands B, C, D is the purchase

duplication for these respective pairs of brands. A widespread

empirical generalization is that the proportion of A buyers who also

buy brands B, C, D generally falls in-line with the brand size of B, C, D.

That is, a brand will share more of its customers with bigger brands

than with smaller brands (Ehrenberg, Uncles, & Goodhardt, 2004).

Likewise, the average proportion of any brand's buyers who also buy

any particular brand such as B should be similar.

The duplication analysis highlights exceptions to the general

purchase-sharing pattern, identifying groups of brands that compete

more or less intensely against each other than they do with the rest of

the market. A partition is the term given to such groups (e.g., Kalwani

& Morrison, 1977). Recognizing partitions is important, because sales

gains by one brand in a partition will come unduly at the expense of

other brands in the partition. The present study utilizes the purchase

duplication approach to examine how buyers of PLs and NBs also buy

other PLs and NBs in the same category, and to identify if PL brands

form a competitive partition.

A statistic called the duplication coefcient (D-coefcient) identies

the extent of competitive intensity. The duplication coefcient is

calculated as average brand duplication / average brand penetration. A

duplication coefcient of 2, for example, estimates the expected

proportion of A buyers who also buy B, is 2 times the penetration of

brand B. To take the example further, consider four brands A, B, C, and D.

The rst two brands (A, B) are PLs of competing retailers. Brands C and D

represent NBs. Next, consider for illustration that the D-coefcient for

the pair of PL brands (% of A buyers who buy B, and vice versa) is 4.0. The

D-coefcients for PL brand buyers who also buy NBs (% of A buyers who

buy C, & D; the % of B buyers who buy C, & D; and vice versa) is 2.0. The

D-coefcient within the group of PLs is twice that of the gure for PL

buyers who also buy NBs. The higher coefcient for PL indicates

competition between the group of PLs is two times stronger than the

competition between the PLs and the NBsgiven the market shares of

all the respective brands. Note that if a retailer offers multiple PLs in the

form of sub-brands (such as Tesco, Tesco Finest and Tesco Value), the

duplications between the parent PL and its sub-brands are not included

in the analysis here. The reason for not including the PLPL sub-brand

duplications is that they would inate the estimate of PL cross-buying.

The focus of the study is buying PL across retailers, not within a single

retailer.

4. Data, analysis and results

The analysis covers 27 categories over a 52-week time period. The

categories are diverse covering food, cleaning, pet care, over the

counter pharmaceuticals, and personal care. The categories also vary

considerably in terms of purchase frequency, ranging from 50

occasions per year for bread, to three occasions per year for batteries,

pepper and cough liquid. Diversity in buying frequency adds

generalizability to the results. TNS provided the data from its UK

Superpanela 15,000-member panel in which consumers electronically record their purchases. The panel is geographically and

demographically representative of the UK shopper population. All

27 categories in the analysis contain multiple NBs, as well as the PLs of

different retail chains. Using data comprising purchases across

multiple retailers is a major advantage over other data sets used in

private-label research, which usually cover only one retailer (e.g.

Hansen, Singh, & Chintagunta, 2006). Some previous studies focus on

specic geographic areas to enable comparison across retailers with

limited geographic presence (e.g., Ellis & Uncles, 1991). This study

analyzes retailers with national distribution coverage.

Table 2

Purchase duplication table for colas. TNS data, UK, one-year period.

% Who also bought

NB

Pen

NB

PL

Dt Coke (D)

Pepsi (P)

Coca Cola (CC)

Coke Zero (CZ)

Ave. duplication

Ave. penetration

D-coefcient

Tesco (T)

Asda (A)

Sainsbury (S)

Morrisons (M)

FreewayLidl (F)

Tesco value (TV)

Ave. D.

Ave. pen.

D-coefcient

35

33

34

14

9

6

4

3

3

2

D

52

45

70

44.9

29.0

1.5

48

48

48

45

39

41

39.5

29.0

1.4

PL

P

CC

CZ

TV

48

44

47

28

26

21

12

14

10

14

6.3

4.5

1.4

9

11

8

9

5

5

4

6

3

5

3

4

3

5

4

4

3

4

2

4

22

(DNBPL)

14

10

10

12

9

8

12

8

12

45

61

51

50

55

49

59

54

49

(DNBNB)

40

42

41

42

41

34

Pen. = Penetration, D = Average Duplication/Average Penetration.

a

The PLPL result does not include duplications between Tesco and Tesco value.

(DPLNB)

22

20

24

19

18

22

32

36

33

25

a

14a

4.5

3.1

18

28

25

10

12

10

6

(DPLPL)

11

9

10

4

4

8

8

J. Dawes, M. Nenycz-Thiel / Journal of Business Research 66 (2013) 6066

Preparing a duplication table is the rst step of analysis. Table 2 is

an example. Splitting the brands into two groups, NBs and PLs, is the

next step. The purchase duplications within and across each of the

two groups form four quadrants: NB buyers who also buy other NBs;

NB buyers who also buy PLs; PL buyers who also buy other PLs; and PL

buyers who also buy NBs. Brands are ordered by market share within

each group. Using this tabular method identies the competitive

interplay between and within the two brand groups, PL and NB.

To clarify the meaning of the table, consider Diet Coke, the biggest NB

in the cola category. Reading across the row for Diet Coke, the table

shows that over a one-year period 35% of consumers bought Diet Coke.

Of those Diet Coke buyers, 48% also bought Pepsi, 44% also bought Coca

Cola, down to 3% also buying Freeway and 3% also buying Tesco Value.

The gures in that row represent the purchase duplications for Diet

Coke, and they follow a pattern called the Duplication of Purchase Law

(Ehrenberg et al., 2004), namely that brands share their customers with

competing brands in-line with the size (penetration) of those

competing brands.

Turning to the PL brands more specically, of the consumers who

bought Tesco cola, 48% also bought Diet Coke, 50% bought Pepsi, and

smaller proportions bought the other national brands. Tesco cola buyers

also bought other PL brands, for example 22% also bought Asda, 14%

bought Sainsbury and so on. The key point is that the buyer of a focal

brand has an expected probability of buying any other particular brand,

with the size (penetration) of the other brand largely dictating that

purchase probability (Ehrenberg, 2000). However, are shoppers who

buy the PL of one retailer more likely to buy another retailer's PL than

would be expected, given the penetrations of those other PLs? The

purchase duplication analysis outlined below answers that question.

Duplication (D) coefcients for the PL and NB brand groups identify

whether buyers of one PL unduly buy the PLs of another retailer. Table 1

indicates these D-coefcients in bold. There are two D-coefcients for

the purchase duplication within each brand groupone for PL (DPLPL),

and one for NB (DNBNB). There are also two D-coefcients showing the

purchase duplication between the brand groups (DPLNB, DNBPL). For the

63

Cola category, the D-coefcient for PLs is 3.1. The gure of 3.1 indicates

that the proportion of PL brand buyers who buy another PL in a different

store is 3.1 times the average penetration for the group of PLs sold at

different stores. In contrast, the D-coefcient for PL buyers to also buy

NBs is 1.4, in other words 1.4 times the penetration of NBs. The higher

D-coefcient for PLs indicates stronger competition between the group

of PL brands than should occurthe rate at which PL buyers buy other

PLs is 2.2 times (1.4 2.2 = 3.1) higher than expected, given the

respective penetrations of the PLs and the NBs. The study uses a

permutation method to calculate the statistical signicance of partitions

as outlined in Appendix A.

Results across the 27 categories (see Table 3) indicate that

heightened competition between the PL brands is common. In some

other categories the PL brands exhibit lessened competitionthat is, a

buyer of one retailer's PL is less likely to buy the PL of another retailer

than would be expected given the overall market share of the PLs in the

category. These ndings suggest there could be category characteristics

that help explain the intensity of competition seen among the private

labels from different stores.

5. Explaining the variation in PL competitive intensity

Examined next are three factors that could account for some of the

varying intensity of PL competition across retailers. The three factors

are category purchase frequency, the price relativity between PLs and

NBs in the respective category, and the extent of manufacturer brand

promotions.

Firstly, categories with higher purchase frequency are more likely to

show PL partitioning. Examples of more heavily bought categories are

colas and cereal, compared with less frequently bought products such as

toothpaste or mustard. A higher rate of category purchasing corresponds to greater cross-shopping across retailers (e.g., Narasimhan &

Wilcox, 1998) because frequent purchasing affords opportunity to shop

at multiple stores. The second explanatory factor relates to reference

price. The traditional appeal of PL brands is their lower price compared

Table 3

Private label competition in 27 categories. TNS data, UK, one-year period.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

a

Product

category

PL market share

in this category

Extent of PL partitioning

(higher = more intense PL

partitions across retailer)

Category

purchase frequency

Price ratio (PL price as

proportion of NB price)

1 = parity

Proportion of manufacturer

brand volume sold on

promotion

Porridge

Colas

Nappies

Tea bags

Toothpaste

Baked Beans

Whisky

Yoghurt

L'dy Detergent

Bread

Deodorant

RTE cereal

Margarine

Soup

Prem. ice cream

Fromage

Cat food

Mineral water

Analgesics

Toilet tissue

Lollies/treats

Frozen pizza

Liquid bleach

Pepper

Herbs

Batteries

Cough liquid

Average

32

14

30

21

16

47

41

36

21

53

15

28

24

25

36

33

42

58

63

45

15

40

60

63

66

30

30

37

2.7a

2.2a

1.7a

1.6a

1.6a

1.6a

1.5a

1.4a

1.4a

1.4a

1.4a

1.3a

1.3a

1.2a

1.1

1.1

1.1

1.0

1.0

1.0

1.0

1.0

.9a

.9a

.8a

.8a

.8a

1.3

7.0

37.0

17.0

7.0

6.0

19.0

11.0

25.0

11.0

44.0

9.0

24.0

14.0

6.0

5.0

12.0

27.0

13.0

11.0

15.0

7.0

8.9

7.0

3.0

3.6

3.0

2.7

13

.38

.33

.80

.60

.47

.60

.86

.80

.70

.88

.40

.70

.66

1.0

1.0

.77

.40

1.0

.50

.95

1.0

.80

.70

.50

.50

.75

.52

.70

.35

.51

.37

.47

.46

.21

.40

na

.50

.11

.39

.31

.23

.42

.50

.36

.28

.26

na

.53

.23

.59

.14

.09

.10

na

.17

.33

Indicates statistically signicantly higher (if N 1) or lower (if b1) cross-purchasing at the p b .05 level.

64

J. Dawes, M. Nenycz-Thiel / Journal of Business Research 66 (2013) 6066

to NBs (Baltas, 1997). Past prices encountered by the shopper inuence

reference price (e.g., Hardie, Johnson, & Fader, 1993) and cause

resistance to paying prices higher than the referent. If the PL brands

tend to sell at a price ratio that is small compared to the average NB in

the category (for example, if the PL price is 60% of the price of the

average NB), then the shopper who buys PLs at one chain will have a

lower reference price for the category. Therefore, when that shopper

buys from the same category at a rival chain, they will seek a brand in the

acceptable range around their reference price. If the PL of the rival

retailer is in the same range as the shopper's reference level, the rival

retailer's PL has a higher chance of purchase. In summary, categories in

which PL prices are well below NBs will show heightened cross-retailer

PL purchasing. The PL price ratio calculation is:

PL Price Ratio = Average PL price = Average NB price

A price ratio of 1.0 indicates parity between the PLs and NBs. A

price ratio of .7, for example, indicates the average PL price is 70% of

the average NB price.

Finally, the extent of NB price promotions could heighten

private-label partitioning. If NBs are frequently price-promoted,

consumers become more price sensitive (Kaul & Wittink, 1995) and

engage in more deal-to-deal buying (Mela, Gupta, & Lehmann, 1997).

Higher price sensitivity could reinforce preference for PLs. The reason

is that prices for PLs are still generally below NBs, even when the latter

are temporarily reduced. Likewise, more deal-to-deal buying could

result in shoppers choosing among the various NBs for a promoted

item. The outcome is higher rates of purchasing within the group of

PLs and within the group of NBs, but less purchasing across them.

OLS regression tested the explanatory power of these three

variables, namely category purchase frequency, the PL price ratio

and manufacturer brand promotions. Table 4 shows the results of the

regression.

The regression analysis explains 31% of the variance in PL

partitioning. The three independent variables are all statistically

signicant at p .05. The results show that PL brands compete especially

intensely in categories with higher purchase frequency. PL brands also

compete more intensely in categories where the average PL sells at a

smaller proportion of the average NB price. The negative coefcient for

PL price ratio indicates a lower PL ratio equates to higher levels of PL

competition. Third, categories with higher incidence of manufacturer

brand promotions show heightened intensity of competition among PLs

of different chains. By contrast, in product categories with lower

purchase frequency, where the PL brand's prices are more in accordance

with NBs, or where there are fewer NB price promotions, the PLs

compete more against NBs and not as intensely against each other.

6. Summary and implications

This paper examines the competition between PLs and NBs in 27

consumer goods categories in the UK. The ndings indicate there are

Table 4

Second-stage regression.

B

S.E

t-ratio

Dependent variable:

PL partition strength

Independent variables:

Intercept

Purchase frequency

(average purchase occasions in 12 months)

Price ratio of PL to NB

% of NB volume sold on promotion

Adjusted R2

1.28

.014

.82

1.17

.31

.29

.007

.34

.48

4.5

2.1

.00

.05

2.4

2.4

.02

.02

categories in which many buyers of the PL of one retailer are as likely,

or more likely, to also buy the PL of another retailer in the same

categorythan would be expected given the overall popularity of that

other PL. The fact that a shopper must buy the other PL in a different

retailer does not necessarily dampen the probability they will buy that

PL in the course of a year. In categories that are purchased more often,

where the PL brands are typically well below the price of the NB's, and

in which there are frequent NB promotions, competition is heightened

between the PLs of different retailers.

The results provide important managerial and academic implications. First, the ndings imply that competition between PLs and NBs

occurs across multiple stores the shopper buys from in a one-year

period. Therefore, researchers who conduct future studies on PL

competition or PL image should obtain data across stores, and not just

within a store. Looking at competition narrowly by focussing on one

retailer hampers the ability to detect the full extent of competition

between all NBs and all PLs. Yet, the majority of retailers still rely on

narrow one retailer information when they mine their loyalty program

databases. A better comprehension of market structure and buyer

behavior based on PL competition across stores would help managers

consider appropriate competitors while mapping out their own

strategy.

Another implication is that since PLs compete more intensely with

other PLs than with NBs in some categories, PL growth may sometimes

hurt other PLs more so than NBs. This result highlights the importance of

PL marketers looking at competition between the two types of brands

across stores, and regarding PLs from other retailers as close competitors. Likewise, for the manager of a NB worried about the growth of a

particular PL, the results indicate those category characteristics in which

other PLs could bear the brunt of the particular PL's growth, rather than

NBs. A further implication for NB owners concerns the nding that many

consumers conne their purchases to PL brands in categories where

there are frequent NB promotions. Therefore, frequent promotions may

not be a good way for NBs to recover market share from PLs.

The fact that in many of the studied categories, consumers will buy a

PL regardless of the store the PL belongs to implies many PLs do not

create exceptional store loyalty. This nding therefore supports past

literature (e.g., Ailawadi, Pauwels, & Steenkamp, 2008; Kumar &

Steenkamp, 2007) and extends that literature by explaining which

category characteristics impact on PLs ability to differentiate retailers.

PLs in categories with lower purchase frequency, with a larger price ratio

relative to national brands, and with lower levels of NB promotions have

higher potential to differentiate a store from competitors. Therefore,

retailers who want to use PLs as a way to increase their store loyalty

should invest in good quality, higher priced PLs, in less frequently

bought categories such as laundry detergent or shampoo. PLs that are

much cheaper than NBs, especially in frequently bought categories, can

attract value-driven, cherry-picking customers, who will buy a cheap PL

anywhere they can nd it. As Corstjens and Corstjens (1999, p. 204)

note, shoppers are indifferent between low-price PLs in frequently

bought, commodity-like categories. PLs in categories that require

purchases several times a week, such as bread, milk, vegetables or

meat are not likely to build store loyalty because consumers usually buy

those goods on ll-in shopping trips, which are likely to occur in several

stores. However, having PLs in such categories helps to create store

trafc, which is another important retailer objective.

The nding that PLs may fail to create high store loyalty also provides

a recommendation for the PL branding strategy best suited to increase

the link between a PL and its retailer: use the retailer's name explicitly in

the PL brand name. Even though using a store name in the name of a PL

may be risky, such a strategy allows differentiation of the PLs of one

retailer from another. The retailer's name also provides a link for the

consumer to associate a PL to a particular retailer or store (as per Kumar

& Steenkamp, 2007). Furthermore, any advertising activity for the

retailer / store may transfer to the PLs if the retailer uses the same brand

name in its PL name.

J. Dawes, M. Nenycz-Thiel / Journal of Business Research 66 (2013) 6066

7. Limitations and future research

The study used a sizable and diverse set of 27 product categories,

however the categories are all fast-moving consumer goods. The limits

of this sample mean the study is not generalizable to broader market

contexts in which PLs are common, for example clothing, prescription

medicine or home-ware. Another limitation is that the data all come

from one geographic market, namely the UK. Replication across other

sectors and countries will establish sound generalizations. Multi-retailer

shopping similar to the UK is found in China (Uncles & Kwok, 2009) and

Japan (Keng, Uncles, Ehrenberg, & Barnard, 1998) indicating generalizable results about PL competition are possible.

Another limitation is that the study did not examine partitioning

between the very cheap value ranges of PLs such as Tesco value, but

rather focused on the mid-tier PL brands. Given the current

three-tiered PL price/quality strategy in the majority of retailers

(Geyskens, Gielens, & Gijsbrechts, 2010), future research could

investigate if price-quality tiers affect PL partitioning across stores.

Next, analysis of additional categories and variables such as

advertising intensity or quality differences between PL and NB could

account for more of the variation in PL partitioning. Finally, the effect

of complementary purchases on cross-retailer PL buying is an

intriguing avenue for future research. For example, are there shopper

characteristics such as heavy-basket or value-conscious buying that

correspond to higher cross-buying of PLs across retailers? Insights

into shopper or basket characteristics would add to research by

Ailawadi et al. (2008) and Hansen and Singh (2008) that nd heavy

store brand buyers (those who buy private labels for many categories)

are not store loyal. Knowing the composition of shopping baskets

would help identify individual-level factors contributing to higher

cross-buying of PLs across stores.

Appendix A. Statistical testing

Consumers buy multiple NBs and PLs in a time period so the

purchase record data used in the study are multinomial. While the

purchase duplication tables resemble a contingency table, usually

analyzed using log-linear methods, the multinomial characteristic

makes the data unsuitable for log-linear models (e.g., Agresti, 2002).

Therefore, the statistical signicance of partitions is assessed using a

permutation method, building on an approach proposed by Loughin and

Scherer (1998). Specically, a visual basic program repeatedly draws

random samples from an extremely large population. Each draw is of the

same sample size, number of brands, and brand penetrations as the

product categories used in the present study. Purchase duplications

between the PL and NB brands are set as equal to test the null hypothesis

of no difference between the groups of PL and NB brands. The program

records the purchase duplication between PL and NB brands for each

sample. Over a series of 10,000 iterations, the procedure reveals the

probability of observing differences in the purchase duplication

coefcients of a particular magnitude. Where the difference in the

duplication coefcients is less than 5 percent likely to occur due to

random sampling variation, the difference is statistically signicant.

References

Agresti A. Categorical data analysis. New Jersey: Wiley; 2002.

Ailawadi KL, Neslin SA, Gedenk K. Pursuing the value-conscious consumer: store brands

versus national brand promotions. J Mark 2001;65:7189.

Ailawadi KL, Pauwels K, Steenkamp J-BEM. Private-label use and store loyalty. J Mark

2008;72(6):1930.

Baltas G. Determinants of store brand choice: a behavioral analysis. J Prod Brand Manag

1997;6(5):31524.

Baltas G, Argouslidis PC. Consumer characteristics and demand for store brands. Int J

Ret Distr Manag 2007;35(5):32841.

Batra R, Sinha I. Consumer-level factors moderating the success of private label brands.

J Ret 2000;76(2):17591.

65

Blattberg RC, Wisniewski KJ. Price-induced patterns of competition. Mark Sci

1989;8(4):291309.

Bound J, Ehrenberg A. Private label purchasing. Admap 1997;32(7):179.

Bushman BJ. What's in a name? The moderating role of public self-consciousness on the

relation between brand label and brand preference. J App Psych 1993;78(5):85761.

Chen JX, Narasimhan O, Dhar T. An empirical investigation of private label supply by

national label producers. Mark Sci 2010;29(4):73855.

Coe BD. Private versus national preference among lower-and middle-income

consumers. J Retail 1971;47:6172. (3, Fall).

Corstjens J, Corstjens M. Store wars: the battle for mindspace and shelfspace.

Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 1999.

Corstjens M, Lal R. Building store loyalty through store brands. J Mark Res 2000;37(3):

28191.

Cotterill RW, Putsis WMJ. Market share and price setting behavior for private labels and

national brands. Rev Ind Org 2000;17:1739.

De Wulf K, Odekerken-Schrder G, Goedertier F, Van Ossel G. Consumer perceptions of

store brands versus national brands. J Consum Mark 2005;22(4):22332.

Dhar SK, Hoch SJ. Why store brand penetration varies by retailer. Mark Sci 1997;16(3):

20827.

Ehrenberg ASC. Repeat-buying: facts, theory and applications. J Empirical Generalisations in Mark Sci 2000;5:392770.

Ehrenberg ASC, Goodhardt GJ. A model of multi-brand buying. J Mark Res 1970;7:7784.

Ehrenberg ASC, Uncles MD, Goodhardt GG. Understanding brand performance

measures: using Dirichlet benchmarks. J Bus Res 2004;57(12):130725.

Ellis K, Uncles mD. How private labels affect consumer choice. British Food J

1991;93(9):419.

Euromonitor. Private labelpotential in a weakening economy. http://www.portal.

euromonitor.com/Portal/ResultsList.aspx 2007. Accessed January 2011.

Fitzell P. Private labels: store brands & generic products. Westport, Connecticut: AVI

Publishing Company Inc; 1982.

Geyskens I, Gielens K, Gijsbrechts E. Proliferating private-label portfolios: how

introducing economy and premium private labels inuences brand choice.

J Mark Res 2010;47(5):791807.

Hansen K, Singh V. Are store-brand buyers store loyal? An empirical investigation.

Manag Sci 2008;54(10):182834.

Hansen K, Singh V, Chintagunta P. Understanding store-brand purchase behavior across

categories. Mark Sci 2006;25(1):7590.

Hardie BGS, Johnson EJ, Fader PS. Modeling loss aversion and reference dependence

effects on brand choice. Mark Sci 1993;12(4):37894.

Hoch SJ, Banerji S. When do private labels succeed? Sloan Manag Rev 1993;34(4).

Kalwani MU, Morrison DG. A parsimonious description of the Hendry system. Manag

Sci 1977;23(5):46777.

Kaul A, Wittink DR. Empirical generalizations about the impact of advertising on price

sensitivity and price. Mark Sci 1995;14(3,2):G15160.

Keng KA, Uncles M, Ehrenberg A, Barnard N. Competitive brand-choice and store-choice

among Japanese consumers. J Prod Brand Manag 1998;7:48194.

Kumar N, Steenkamp J-BEM. Private label strategy: how to meet the store brand

challenge. Boston: Harvard Business Press; 2007.

Lincoln K, Thomassen L. Private label: turning the retail brand threat into your biggest

opportunity. London: Kogan Page Publishers; 2008.

Liu Y. The long-term impact of loyalty programs on consumer purchase behavior and

loyalty. J Mark 2007;71:1935.

Loechner J. Value leads store brand growth; promotion aids brand products. Media Post

Publications. http://www.mediapost.com/publications/?fa=Articles.showArticle&

art_aid=127790 2010. Accessed January 2011.

Loughin TM, Scherer PN. Testing for association in contingency tables with multiple

column responses. Biometrics 1998;54:6307.

Marian P. Talking shop: UK grocers focus on private-label innovation. http://www.justfood.com/analysis/uk-grocers-focus-on-private-label-innovation_id112556.aspx

2010. Accessed January 2011.

Mela CF, Gupta S, Lehmann DR. The long-term impact of promotion and advertising on

consumer brand choice. J Mark Res 1997;34:24861.

Meyer-Waarden L, Benavent C. The impact of loyalty programs on repeat purchase

behaviour. J Mark Manag 2006;22(1/2):6188.

Morton FS, Zettelmeyer F. The strategic positioning of store brands on retailer

manufacturer negotiations. Rev Ind Org 2004;24(2):16194.

Narasimhan C, Wilcox RT. Private labels and the channel relationship: a cross-category

analysis. The J of Bus 1998;71(4):573600.

Nies S, Natter M. Are private label users attractive targets for retailer coupons? Int J Res

Mark 2010;27(1):28191.

Parker P, Kim N. National brands versus private labels: an empirical study of

competition, advertising and collusion. Eur Manag Jnl 1997;15(3):22035.

Pauwels K, Srinivasan S. Who benets from store brand entry? Mark Sci 2004;23(3):

36490.

Quelch JA, Harding D. Brand versus private labels: ghting to win. Harv Bus Rev 1996;1:

99109.

Raju JS, Sethuraman R, Dhar SK. The introduction and performance of store brands.

Manag Sci 1995;41(6):95778.

Sayman S, Hoch SJ, Raju JS. Positioning of store brands. Mark Sci 2002;21(4):37897.

Sethuraman R. A model of how discounting high-priced brands affects the sales of

low-priced brands. J Mark Res 1996;33:399409.

Sethuraman R. Private-label marketing strategies in packaged goods: management

beliefs and research insights. Working paper series, Marketing Science Institute;

2006.

Sethuraman R, Cole C. Factors inuencing the price premiums that consumers pay for

national brands over store brands. J Prod Brand Manag 1999;8(4):34051.

66

J. Dawes, M. Nenycz-Thiel / Journal of Business Research 66 (2013) 6066

Sethuraman R, Srinivasan V. The asymmetric share effect: an empirical generalization

on cross-price effects. J Mark Res 2002;39(8):37986.

Steiner RL. The nature and benets of national brand/private label competition. Rev Ind

Org 2004;24(2):10527.

Uncles MD, Ellis K. The buying of own labels. Eur J Mark 1989;23(3):4770.

Uncles M, Hammond K. Grocery store patronage. Int Rev Retail Dist Consum Res

1995;5(3):287302.

Uncles M, Kwok S. Patterns of store patronage in urban China. J Bus Res 2009;62(1):6881.

Uncles MD, Dowling GR, Hammond K. Customer loyalty and customer loyalty

programs. J Consumer Mark 2003;20(4):294317.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Acf 02Document16 pagesAcf 02Allan AlvesPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Journal of World Business: Alvaro Cuervo-CazurraDocument15 pagesJournal of World Business: Alvaro Cuervo-CazurraAllan AlvesPas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Model Fit Summary CminDocument2 pagesModel Fit Summary CminAllan AlvesPas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- How Embarrassing!: An Exploratory Study of Critical Incidents Including Affective ReactionsDocument14 pagesHow Embarrassing!: An Exploratory Study of Critical Incidents Including Affective ReactionsAllan AlvesPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Full Text 01Document85 pagesFull Text 01Allan AlvesPas encore d'évaluation

- Business Research QuarterlyDocument16 pagesBusiness Research QuarterlyAllan AlvesPas encore d'évaluation

- Harley's Corner Positioning Dilemma.Document4 pagesHarley's Corner Positioning Dilemma.Nikita sharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Career Objective For A Fresher EngineerDocument4 pagesCareer Objective For A Fresher Engineerlisa arifaniaPas encore d'évaluation

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Identify The Market Problem To Be Solved orDocument10 pagesIdentify The Market Problem To Be Solved orRaymond DumpPas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- To Generate Facility Plans, The Following Questions Must Be AnsweredDocument30 pagesTo Generate Facility Plans, The Following Questions Must Be AnsweredPuneet GoelPas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Tally - Accounting Package Software: Shyam Sunder GoenkaDocument23 pagesTally - Accounting Package Software: Shyam Sunder GoenkaLeo ThugsPas encore d'évaluation

- Financial Instruments Cost of Capital Qs PDFDocument28 pagesFinancial Instruments Cost of Capital Qs PDFJust ForPas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Early Career Masters ProgrammesDocument20 pagesEarly Career Masters ProgrammesAnonymous dNcT0IRVPas encore d'évaluation

- Stacey Rosenfeld Resume 2018Document1 pageStacey Rosenfeld Resume 2018api-333865833Pas encore d'évaluation

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Cir Vs Dlsu, GR No. 196596, November 9, 2016Document3 pagesCir Vs Dlsu, GR No. 196596, November 9, 2016Nathalie YapPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Overeign Funds Flow Ndia Replaces Hina As Most Sought After DestinationDocument18 pagesOvereign Funds Flow Ndia Replaces Hina As Most Sought After DestinationABHINAV DEWALIYAPas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- Nestle Success StoryDocument3 pagesNestle Success StorySaleh Rehman0% (1)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Audit Process: Principles, Practice and Cases Seventh EditionDocument28 pagesThe Audit Process: Principles, Practice and Cases Seventh EditionSyifa FebrianiPas encore d'évaluation

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Coors UaeDocument14 pagesCoors UaeSamer Al-MimarPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Sustainability Report 2021Document27 pagesSustainability Report 2021Eugene GaraninPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Epaycard - Terms Conditions - 2017 NewDocument1 pageEpaycard - Terms Conditions - 2017 NewDrw ArcyPas encore d'évaluation

- Group 5.scrum MethodologyDocument11 pagesGroup 5.scrum Methodologysimon MureithiPas encore d'évaluation

- VTU Question Paper On Security AnalysisDocument56 pagesVTU Question Paper On Security AnalysisVishnu PrasannaPas encore d'évaluation

- Revision Notes Book Corporate Finance Chapter 1 18Document15 pagesRevision Notes Book Corporate Finance Chapter 1 18Yashrajsing LuckkanaPas encore d'évaluation

- ENT600 G3 NPD Project - TGGL SummaryDocument23 pagesENT600 G3 NPD Project - TGGL SummaryFahmi YahyaPas encore d'évaluation

- MCQ PDD Unit 4Document10 pagesMCQ PDD Unit 4kshitijPas encore d'évaluation

- Key Performance Indicators - KPIs - For Learning and TeachingDocument4 pagesKey Performance Indicators - KPIs - For Learning and Teachingxahidlala0% (1)

- Digital Pharmaceutical Marketing StrategiesDocument21 pagesDigital Pharmaceutical Marketing StrategiesdanogsPas encore d'évaluation

- Garcia, Phoebe Stephane C. Cost Accounting BS Accountancy 1-A CHAPTER 10: Process Costing True or FalseDocument26 pagesGarcia, Phoebe Stephane C. Cost Accounting BS Accountancy 1-A CHAPTER 10: Process Costing True or FalsePeabeePas encore d'évaluation

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Asset Financial System and Costing Training GBP 20-21 Mar2013Document43 pagesAsset Financial System and Costing Training GBP 20-21 Mar2013Erwin Suryadi Rahman100% (1)

- BIR NO DirectoryDocument48 pagesBIR NO DirectoryRB BalanayPas encore d'évaluation

- Financial ServicesDocument2 pagesFinancial ServicesAlok Ranjan100% (1)

- Magaya Cargo System OperationsDocument17 pagesMagaya Cargo System OperationsMohammed Al-GhannamPas encore d'évaluation

- 923000867864Document240 pages923000867864Ahmad Noman100% (1)

- Idterm XAM: Acct Pring Nstructor Peter HENDocument12 pagesIdterm XAM: Acct Pring Nstructor Peter HENbernicePas encore d'évaluation

- Enotesofm Com2convertedpdfnotesinternationalbusiness 100330064505 Phpapp01Document291 pagesEnotesofm Com2convertedpdfnotesinternationalbusiness 100330064505 Phpapp01Hari GovindPas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)