Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Gaydarska&Chapman

Transféré par

Kavu RICopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Gaydarska&Chapman

Transféré par

Kavu RIDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Geoarchaeology and Archaeomineralogy (Eds. R. I. Kostov, B. Gaydarska, M. Gurova). 2008.

Proceedings of the International Conference, 29-30 October 2008 Sofia, Publishing House St. Ivan Rilski, Sofia, 63-66.

THE AESTHETICS OF COLOUR AND BRILLIANCE OR WHY WERE PREHISTORIC

PERSONS INTERESTED IN ROCKS, MINERALS, CLAYS AND PIGMENTS?

Bisserka Gaydarska, John Chapman

Durham University, Durham, United Kingdom; b_gaydarska@yahoo.co.uk; j.c.chapman@durham.ac.uk

ABSTRACT. The authors present an exploration of why prehistoric persons were so interested in highly coloured and shining objects. They

propose an aesthetic of colour and brilliance that emerged in the Balkan early farming period and developed as a key feature in the Climax Balkan

Copper Age, influencing all forms of material culture and underpining the dazzling development of goldworking technology represented in the Varna

Chalcolithic cemetery.

shiny objects was an act of transformative creation, trapping

and converting ... the fertilising energy of light into brilliant solid

forms (Saunders, 2003, 21). These shiny objects became

objects of social prestige, centrally located in the symbolic

representation of political power and elite status. Here,

Saunders specifies the religious beliefs which underpin a very

specific transformation of the material world.

Introduction

In a conference devoted to archaeogemmology (archaeomineralogy), we should be disappointed not to find important

summaries of new empirical findings, especially

characterisation studies and technological analyses. The

findings on facetting of carnelian beads in the Varna

Chalcolithic cemetery (Kostov, 2007), awaken us to the

extraordinary achievements of prehistoric craftspersons in

making visually stunning objects.

Building on these insights, we can start to develop the basis

for a materially-based aesthetic linked to persons, practices

and things. The epicentre of the aesthetic is the valuation of a

quality or qualities in the material world which, by dint of a

close physical match, symbolises to a high degree one or more

core religious beliefs held to underpin society. To the extent

that the objects exhibiting the key quality/ies are the products

of high craft skill, the link between making the object and

reinforcing its ritual connotations becomes stronger and the

more mystic and enchanting the technology involved in this

transformation of nature into cultural order. Insofar as the

makers take on the qualities of the objects, they become ritual

specialists who reinforce the cosmological associations of the

objects.

Less obvious, perhaps, is why prehistoric persons should

bother to expend such energy in the making of things not just

the time needed to make a polished stone axe but the

embodied skills built up over many years. Is there an

underlying rationale behind the production of colourful and

shining objects in prehistory? In this short contribution, we

seek to summarise one possible dimension the existence in

the Balkan Neolithic and Chalcolithic of an aesthetic of colour

and brilliance based on an explicit valuation of such qualities in

an object. Such a valuation is, in turn, based upon the ritual

values embedded in bright, colourful objects. For an

explanation of the link between aesthetics, ritual and values,

we turn to social anthropology.

to

Shine and colour among Balkan early farmers

(6300-5300 BC)

Many ethnographers have made the connection between

distinctive colours, brilliant surfaces and ritual power and

potency. One leading researcher makes this claim in ways that

are of particular interest to us. Nick Saunders has identified

shininess as a key element of an aesthetic of pan-Amerindian

metalworking (Saunders, 2003). Saunders identifies

widespread values placed on shiny matter also often of

distinctive colour, such as gold derived from pan-Amerindian

beliefs about the spiritual and creative power of light. Because

they were believed to be physical representations of light,

brilliant objects were seen as charged with cosmological

power. Saunders summarises the case by stating that Making

There is good grounds for accepting that the earliest farmers

of the Karanovo I/II, Kremikovci, Starevo, Cri and Krs

regional groups of the Early Neolithic exchanged and/or

acquired small numbers of sacred items from beyond their

daily territories (Chapman, 2007). These objects created and

enriched a new visual identity for this period, based upon the

striking colours and brilliance of fine painted, slipped and

burnished pottery. Whether local or exotic in origin, all of the

major artifact classes contributed to this identity most of all

pottery, because it was so common in the household and the

settlement - but also polished stone ornaments and tools,

animal and human bone, burnt things, marine shell ornaments

of Spondylus gaederopus and objects made of copper or

Social

anthropological

prehistoric aesthetics

background

63

copper minerals. These objects extended both the colour

spectrum and the range of shine of the foraging world (Bori,

2002). Increasing numbers of coloured and shining objects

broadened the possibilities for metaphorical links between

objects with the same colour whether the red of the copper

awls, the burnished red bowls and the autumn leaves or the

green of the malachite beads, the nephrite sceptres and

swastikas and fresh vernal growth. This visualisation of the

symbolic properties of exotic objects manifested in distinctive

colours and polished textures created a public and

spontaneous excitement that linked such objects and their

owners to the numinous and the remote, as well as to the

world of the ancestors. It was the creation of new relations

through objects of colour and brilliance that helped in the

making of new worlds in the Neolithic (Whittle, 1996).

crystal or alabaster animal heads of the Vina group

(Chapman, 1981) or the lighter polished stone axes, whose

huge increase in production related to their frequent use as

stone hoes as well as their symbolic importance in linking up

different places in the landscape. The increasing use of copper

objects, especially as grave goods, provides another colour

contrast to obsidian. The strongest colour contrast with black

pottery and obsidian came with the predominantly white

seashells of the genus Spondylus gaederopus, which formed

Europes first long-distance exchange network, connecting the

Aegean to the Paris Basin in the late VI mill. BC (Sfriads,

2003).

A detailed study of the depositional context of exotic objects

(Chapman, 2007) indicated that stone and shell ornaments

were more frequently found outside rather than inside the

house. In addition, all classes of exotic objects except metals

were found with burials, showing their personal links with the

newly dead. Thirdly and tellingly, exotic objects were generally

excluded from ritual contexts vital for the social reproduction of

early farming communities, because their meanings were too

different from those of local objects to gain local ritual

significance.

The overwhelming impression from many classes of climax

Copper Age objects is a high level of diversity combined with

increased scales of production. This diversity is linked to

complex communities consisting of persons with both novel

skills (copper-smelting, weaving, cheese-making, etc.) or

traditional skills (axe-making, potting, figurine-making)

(Chapman, Gaydarska, 2006). Two of the key elements in the

material environment of these groups are colour and brilliance.

Aesthetic elaboration in the Climax Balkan

Copper Age (4800/4700-4000 BC)

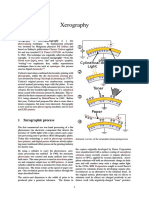

No-one looking at the finely produced painted wares of the

Cucuteni-Tripolye groups (Mantu, Dumitroaia, 1997) could fail

to be impressed with their bold colours, dramatic motifs and

surface polish, especially in comparison with the variegated

shell-tempered wares and other coarse and medium wares.

Similarly, the principal ceramic innovation of the

Kodzhadermen-Gumelnia-Karanovo VI group graphite

painting (Todorova, 1978) created the effect of silver motifs

shimmering on the surface of the vessel, like the rays of the

moon on the Danube at night. The large quantities of bright,

colourful vessels in and around houses in most settlements of

these groups provided continuous visual recall of a community

aesthetic that was visually well established.

Mature farming communities

(5300-4800/4700 BC)

In the late phase of the early farming period, dark burnished

fine wares spread across the southern Balkans (Garaanin,

1954), as new pottery assemblages in strong contrast to the

local traditions of light-faced painted wares. The virtual

disappearance of painted wares at the start of the mature

farming period was perhaps a sign of the decisive

strengthening of some social groups over others.

Balkan prehistorians have generally overlooked two

fundamental traits of dark burnished ware, viz., the surface

colour and brightness of the pottery. Considerable firing skills

were required to produce completely reducing firing conditions,

which differentiated the resulting black wares from even

medium and dark grey vessels. The most lustrous black

burnished wares was produced by vitrification of the ceramic

surface at temperatures of cca. 1200oC. The aesthetic result of

these two technical achievements was a startingly attractive

object that shone like an obsidian core, putting all other

ceramics into the shadow. I suggest that the colour symbolism

and aesthetic appeal of dark, and especially black, burnished

and polished wares were of major significance for their gradual

emergence as the preferred fine ware over wide areas of

Anatolia, the Aegean and the Balkans in the late VI and early V

mill. Cal BC. The colour black may have symbolized a wide

range of persons, states of being or places, varying between

regions or even settlements but retaining everywhere its

aesthetic attraction.

The range and diversity of highly coloured, polished objects

in the climax Copper Age is greatly extended by a

consideration of polished stonework. A shining example

concerns the tubular, red carnelian beads a rare class of

mortuary goods found only in the Varna and Durankulak

cemeteries so far. Recent gemmological analyses has

revealed up to 16 fine, perfectly executed faceting on each

tapering side of the beads to produce the reflection of even

more surface brilliance (Kostov, 2007). The close association

of the body of the person with the flashing beads that they

wore, presumably on special ceremonial occasions, created a

lasting aesthetic bond between person and thing. Since there

was no other reason to produce facets other than to create

additional brilliance, carnelian beads serve as an excellent

illustration of climax Copper Age aesthetics.

The biggest expansion in colour came with the increased use

of copper minerals and the creation of a new object-colour

gold. When newly finished, cast or beaten copper objects

presented a shiny brown surface that, like people, could

change appearance with age, becoming more textured and

more variegated in colour. The emergence of heavy cast

copper objects predominantly axes, chisels and daggers

has rarely been discussed in terms of flashing blades, colour

The VI mill. BC peak in black/dark burnished pottery

assemblages provides a visual context for all other bright,

colourful objects. It is surely not a coincidence that the peak in

obsidian exchange networks coincided with this ceramic peak

in the Central Balkans. But most other shiny objects created

colour contrasts with the pottery whether the marble, rock

64

was a pre-requisite for the choice of gold as the key medium at

Varna.

and luminosity (but see Keates, 2002 for Italian Copper Age

daggers). The mounting of blades, whose large surface area

created spectacular brilliance, on finely crafted wooden or

bone handles, in contrasting colour to that of the blade,

increases the objects visual prominence in the performance

where it would be a significant actor.

It is also important to recall that this aesthetic was not

entirely Balkan in origin or development. While the range of

object-colours was noticeably narrower among early farmers in

Central Europe (the Linearbandkeramik) and later worlds to the

North West, or in coeval foraging societies in the North Pontic

zone, farming communities in Greece and North West Anatolia

shared some fundamental object-colours with those in the

Balkans and Hungary not least the earlier painted styles and

the later dark burnished ware traditions. The implications of

gross variations in object-colour range require further

investigation. But it seems highly probable that the Balkan

Neolithic and Chalcolithic played a key role in the spread of an

aesthetic of colour and brilliance to regions further to the North,

North-East and West. In conclusion, we should not forget that

the research skills of geoarchaeologists and archaeomineralogists are fundamental to prehistorians further

understanding of the visual world of material culture that forms

the core of their discipline.

A specific feature of the Varna cemetery is the emphasis on

gold (Ivanov, 1988). Renfrew (1986) has sought to explain the

significance of gold in terms of its permanent colour, the

extraordinary technology of gold painting and the covering of

gold on status objects and important body zones. However, he

misses the more fundamental point that gold is the brightly

coloured, luminous material par excellence with the potential to

make a visually explosive contribution to an aesthetic founded

on colour and brilliance. Indeed, it could be proposed that gold

would never have been selected for the prominence it enjoyed

at Varna without the earlier existence of such an aesthetic! The

relative rarity of gold in mortuary sites other than Varna, as well

as in all domestic contexts, is another sign of the special

aesthetic and political value of gold. While it is doubtful that the

vast majority of Copper Age people ever set eyes on this

material, those who did must have recognized its unique

qualities in Copper Age object-colours (Chapman, 2007a).

References

Bori, D. 2002. Apotropaism and the temporality of colours:

colourful Mesolithic-Neolithic seasons in the Danube

Gorges. In: Colouring the Past. The Significance of

Colour in Archaeological Research (Eds. A. Jones, G.

MacGregor). Berg, Oxford, 23-43.

Chapman, J. C. 1981. The Vina Culture of South East

Europe. Studies in Chronology, Economy and Society. Vol.

1-2. BAR Intern. Series 117, Oxford.

Chapman, J. 2003. Colour in Balkan prehistory (alternatives to

the Berlin & Kay paradigm). In: Early Symbolic Systems

for Communication in Southeast Europe (Ed. L. Nikolova).

BAR Intern. Series 1139, Archaeopress, Oxford, 31-56.

Chapman, J. 2007. Engaging with the exotic: the production of

early farming communities in South-East and Central

Europe. In: A Short Walk through the Balkans. The First

Farmers of the Carpathian Basin and Adjacent Regions

(Eds. M. Spataro, P. Biagi). Quaderno 12. Trieste; Societ

per la preistoria i protostoria della regione Friuli-Venezia

Giulia, 207-222.

Chapman, J. 2007a. The elaboration of an aesthetic of

brlliance and colour in the Climax Copper Age. In:

Stephanos Aristeios. Archologische Forschungen

zwischen Nil und Istros. Festschrift fr Stefan Hiller zum

65. Geburtstag (Eds. F. Lang, C. Reinholdt, J.

Weilhartner). Phoibos Verlag, Wien, 65-74.

Chapman, J., B. Gaydarska. 2006. Parts and Wholes:

Categorisation and Fragmentation in Prehistoric Context.

Oxbow Books, Oxford, 264 p.

Garaanin, M. V. 1954. Iz istorije mljadeg neolita u Srbiji i

Bosne. Glasnik Zemalskog Muzeja u Sarajevu, N.S., 9,

5-39.

Ivanov, I. 1988. Die Ausgrabungen des Grberfeldes von

Varna. In: Macht, Herrschaft und Gold (Eds. A. Fol, J.

Lichardus). Moderne Galerie des Saarland-Museums,

Saarbrcken, 49-66.

Jones, A., G. MacGregor (Eds.). 2002. Colouring the Past. The

Significance of Colour in Archaeological Research. Berg,

Oxford New York, 284 p.

Discussion and conclusions

The social impact of colour and brilliance has been widely

underestimated in European prehistory, although advances

have been made in our understanding of the colouring of the

past (Jones, MacGregor, 2002; Chapman, 2003). If we step

back from the details of the material culture that is excavated in

such profusion in Balkan and Central European prehistory,

what we can appreciate is a colourful world where objectcolours were just as important as environmental colours in the

creation of significance and meaning. The recognition of focal

colours that small group of colours of greatest visual

significance in social practices was related to object-colours

as much as environmental colours and colour terminologies.

The naming of an object-colour, based upon a specific kind of

flint or chert, represented one way to make the world

comprehensible and meaningful. The relation of each objectcolour to every other focal colour led to the development of an

overall system of colour symbolism which gave meaning to the

prehistoric world.

On the most general level, this account of prehistoric objectcolours indicates an overall continuity of aesthetic appreciation

and therefore political significance at the millennial timescale

from cca. 6500-3500 Cal BC. The contribution of colour and

brightness to social identities has been an important one over

100 generations. It is equally clear that communities living in

three successive phases of Balkan prehistory the early

farming period, the mature farming period and the climax

Copper Age each worked out their own particular form of the

shared general aesthetic of colour and brilliance. Three

innovations can be identified as offering particularly great

potential for the emergence of new colour schemes the

introduction of pottery, the emergence of stone-carving and the

development of cast copper metallurgy. Each change allowed

craft specialists and household producers to create new forms

whose surfaces shone and gleamed with colour and brilliance.

In relation to metallurgical colours, a particularly important

suggestion is that it was the antecedent colourful aesthetic that

65

Keates, S. 2002. The flashing blade: copper, colour and

luminosity in North Italian Copper Age society. In:

Colouring the Past. The Significance of Colour in

Archaeological Research (Eds. A. Jones, G. MacGregor).

Berg, Oxford, 109-125.

Kostov, R. I. 2007. Arheomineralogiya na neolitni i halkolitni

artefakti ot Bulgaria i tyahnoto znachenie v gemologyata.

Publising House Sv. Ivan Rilski, Sofia, 124 p., I-VIII (in

Bulgarian with an English abstract).

Mantu, C.-M., Gh. Dumitroaia. 1997. Catalogue. In: Cucuteni.

The Last Great Chalcolithic Civilisation of Old Europe (Eds.

C.-M. Mantu, Gh. Dumitroaia, A. Tsaravopoulos). Athena,

Bucharest, 101-239.

Renfrew, C. 1986. Varna and the emergence of wealth. In:

The Social Life of Things (Ed. A. Appadurai). Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge, 141-168.

Saunders, N. J. 2003. Catching the light: technologies of

power and enchantment in Pre-Coumbian goldworking.

In: Gold and Power in Ancient Costa Rica, Panama and

Colombia (Eds. J. Quilter, J. W. Hoopes). Dumbarton Oaks

Research Library, Washington, D.C., 15-47.

Sfriads, M. L. 2003. Note sur lorigine et la signification des

objets en spondyle de Hongrie dans le cadre du

Nolithique et de lnolithique europens. In: Morgenrot

der Kulturen. Festschrift fr Nndor Kalicz zum 75

Geburtstag (Eds. E. Jerem, P. Raczky). Archaeolingua,

Budapest, 353-373.

Todorova, H. 1978. The Chalcolithic Period in Bulgaria in the

Fifth Millennium B.C. BAR, Intern. Series 49, Oxford.

Whittle, A. 1996. Europe in the Neolithic. The Creation of New

Worlds. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 443 p.

66

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Humor in Public Speaking PDFDocument613 pagesHumor in Public Speaking PDFKASHMIR KASHMIR100% (1)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Contemporary Philippine Arts From The Region Is Your Stepping Stone To Understanding TheDocument9 pagesContemporary Philippine Arts From The Region Is Your Stepping Stone To Understanding TheDondee Palma75% (4)

- Cinder EllaDocument24 pagesCinder EllaIvory Joi Margarejo100% (1)

- Prehistoric Warfare and Violence 2018springer PDFDocument361 pagesPrehistoric Warfare and Violence 2018springer PDFKavu RIPas encore d'évaluation

- Mastering Thracian Kaval OrnamentationDocument194 pagesMastering Thracian Kaval OrnamentationJulian Selody100% (1)

- Getty Musum 11Document226 pagesGetty Musum 11Kavu RIPas encore d'évaluation

- Archaic Greek CultureDocument161 pagesArchaic Greek Cultureserge57100% (4)

- Archaic Greek CultureDocument161 pagesArchaic Greek Cultureserge57100% (4)

- Heyd Europe 2500 To 2200 BC Bet PDFDocument21 pagesHeyd Europe 2500 To 2200 BC Bet PDFKavu RIPas encore d'évaluation

- Weather Architecture 2012Document378 pagesWeather Architecture 2012Rodrigo Ferreyra100% (3)

- Rock Art and Metal TradeDocument22 pagesRock Art and Metal TradeKavu RI100% (1)

- The Kingdom of Mycenae PDFDocument184 pagesThe Kingdom of Mycenae PDFKavu RIPas encore d'évaluation

- Mastering Sketching S11 BLAD Print2Document8 pagesMastering Sketching S11 BLAD Print2Interweave0% (1)

- Cladue Monet and Impressionism Power PointDocument34 pagesCladue Monet and Impressionism Power PointCLEITHN1100% (1)

- Art and Archaeology The Function of The Artist in Interpreting Material CultureDocument281 pagesArt and Archaeology The Function of The Artist in Interpreting Material CultureKavu RIPas encore d'évaluation

- MurganDocument16 pagesMurganKavu RIPas encore d'évaluation

- Archaeology and The Governance of Materi PDFDocument9 pagesArchaeology and The Governance of Materi PDFKavu RIPas encore d'évaluation

- Writing As Material Practice.Document18 pagesWriting As Material Practice.Kavu RIPas encore d'évaluation

- GUSTIN M KUZMAN P The Elitte The Upper VDocument20 pagesGUSTIN M KUZMAN P The Elitte The Upper VKavu RIPas encore d'évaluation

- Gold and Gold Working of The Bronze AgeDocument15 pagesGold and Gold Working of The Bronze AgeKavu RIPas encore d'évaluation

- Immigration and Transhumance in The Earl PDFDocument15 pagesImmigration and Transhumance in The Earl PDFGava Ioan RaduPas encore d'évaluation

- The Chronology of The Macedonian Royal TDocument45 pagesThe Chronology of The Macedonian Royal TKavu RIPas encore d'évaluation

- To Gender or Not To Gender Exploring Gender Variations Through Time and SpaceDocument29 pagesTo Gender or Not To Gender Exploring Gender Variations Through Time and SpaceKavu RIPas encore d'évaluation

- Uckelmann Land - Transport PDFDocument16 pagesUckelmann Land - Transport PDFKavu RIPas encore d'évaluation

- A New Bronze Age Shipwreck With Ingots in The West of Antalya Preliminary ResultsDocument13 pagesA New Bronze Age Shipwreck With Ingots in The West of Antalya Preliminary ResultsKavu RIPas encore d'évaluation

- Duffy2019 PDFDocument22 pagesDuffy2019 PDFKavu RIPas encore d'évaluation

- Mitja GustinDocument8 pagesMitja GustinKatarina JovanovićPas encore d'évaluation

- Kristiansen - From Memory To Monument The ConstructionDocument10 pagesKristiansen - From Memory To Monument The ConstructionKavu RIPas encore d'évaluation

- On The Making of Copper Oxhide Ingots: Evidence From Metallography and Casting ExperimentsDocument11 pagesOn The Making of Copper Oxhide Ingots: Evidence From Metallography and Casting ExperimentsKavu RIPas encore d'évaluation

- Die Bronzemetallurgie in Den Otomani-GemDocument60 pagesDie Bronzemetallurgie in Den Otomani-GemKavu RIPas encore d'évaluation

- S 0003598 X 00081953Document12 pagesS 0003598 X 00081953Kavu RIPas encore d'évaluation

- The Idea of Order The Circular Archetype in Prehistoric Europe Stonehenge Exploring The Greatest Stone Age MysteryDocument7 pagesThe Idea of Order The Circular Archetype in Prehistoric Europe Stonehenge Exploring The Greatest Stone Age MysteryKavu RIPas encore d'évaluation

- KalupDocument13 pagesKalupKavu RIPas encore d'évaluation

- Rock Art and Metal Trade PDFDocument22 pagesRock Art and Metal Trade PDFKavu RIPas encore d'évaluation

- (Volume 144 of Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology and Literature - Pocket-Book) John G. Younger-Music in The Aegean Bronze Age-P. Åströms Förlag (1998) PDFDocument75 pages(Volume 144 of Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology and Literature - Pocket-Book) John G. Younger-Music in The Aegean Bronze Age-P. Åströms Förlag (1998) PDFKavu RIPas encore d'évaluation

- Dating The East Adriatic NeolithicDocument21 pagesDating The East Adriatic NeolithicKavu RIPas encore d'évaluation

- Journal of CosmologyDocument10 pagesJournal of CosmologyKavu RIPas encore d'évaluation

- Karate ChampionshipDocument2 pagesKarate ChampionshipsanthoshinouPas encore d'évaluation

- Experiment#01 (Colour Coding of Resistors)Document3 pagesExperiment#01 (Colour Coding of Resistors)MUHAMMAD SALEHPas encore d'évaluation

- !08 Karanas Kapila VatsyayanDocument12 pages!08 Karanas Kapila VatsyayanDeep GhoshPas encore d'évaluation

- Rozen Maiden - Shukuteki EnsembleDocument13 pagesRozen Maiden - Shukuteki Ensembleapi-3826691Pas encore d'évaluation

- Final Project Exhibition Review SombillaDocument6 pagesFinal Project Exhibition Review SombillaCyan SombillaPas encore d'évaluation

- No.3911, Bin Sheng Road, Bin Jiang District, Hangzhou, ChinaDocument5 pagesNo.3911, Bin Sheng Road, Bin Jiang District, Hangzhou, ChinaMMuzammalPas encore d'évaluation

- Art Final PDFDocument3 pagesArt Final PDFThomas CampbellPas encore d'évaluation

- Tangshan Longway Ceramics Co., LTDDocument43 pagesTangshan Longway Ceramics Co., LTDHailey AttardPas encore d'évaluation

- The Significance of The Symbols of Mirror and Portrait in Teaching SymbolismDocument6 pagesThe Significance of The Symbols of Mirror and Portrait in Teaching SymbolismIJELS Research JournalPas encore d'évaluation

- Street Dance Grassroots 101 (22-23)Document55 pagesStreet Dance Grassroots 101 (22-23)Krizyl VergaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Xer OgraphyDocument5 pagesXer OgraphyPaula ZorziPas encore d'évaluation

- UMC UNI17-28 July 21st, 2017Document47 pagesUMC UNI17-28 July 21st, 2017Universal Music CanadaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ten StudentsDocument12 pagesTen StudentsShoaib AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Subject Name: Honours III: Investment Law Subject Code: 8UG07 Academic Year: 2019-20 Session: January-AprilDocument3 pagesSubject Name: Honours III: Investment Law Subject Code: 8UG07 Academic Year: 2019-20 Session: January-AprilPradhuymn MishraPas encore d'évaluation

- Memory Drawing Online ArtistDocument6 pagesMemory Drawing Online Artistwinofvin9100% (1)

- Separata Computacion 2016 Photoshop OkDocument50 pagesSeparata Computacion 2016 Photoshop OkJ.A García ChoquePas encore d'évaluation

- BWI BrandGuide2021Document14 pagesBWI BrandGuide2021sunny seePas encore d'évaluation

- CM PrantnerDocument4 pagesCM PrantnerNazly AlejandraPas encore d'évaluation

- Does It Look The Same Class 5 Notes CBSE Maths Chapter 5 (PDF)Document7 pagesDoes It Look The Same Class 5 Notes CBSE Maths Chapter 5 (PDF)krishna GPas encore d'évaluation

- Construction of A 2 Storey R.C.C Residential BuildingDocument14 pagesConstruction of A 2 Storey R.C.C Residential BuildingThin Zar OoPas encore d'évaluation

- SyllabusDocument1 204 pagesSyllabusAstro RudraPas encore d'évaluation

- Company Profile Version 1 4Document25 pagesCompany Profile Version 1 4netspecPas encore d'évaluation