Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Ronneberg - The Protective Effects of Religiosity On Depression - A 2-Year Prospective Study

Transféré par

Dini NanamiTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Ronneberg - The Protective Effects of Religiosity On Depression - A 2-Year Prospective Study

Transféré par

Dini NanamiDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The Gerontologist Advance Access published July 25, 2014

The Gerontologist, 2014, Vol. 00, No. 00, 112

doi:10.1093/geront/gnu073

Research Article

The Protective Effects of Religiosity on

Depression: A2-Year Prospective Study

Downloaded from http://gerontologist.oxfordjournals.org/ at University Library, University of Illinois at Chicago on July 31, 2014

Corina R.Ronneberg, MS,* Edward AlanMiller, PhD, MPA,

ElizabethDugan, PhD, and FrankPorell, PhD

Department of Gerontology, John E.McCormack Graduate School of Policy & Global Studies, University

of Massachusetts Boston.

*Address correspondence to Corina R.Ronneberg, MS, Department of Gerontology, John E.McCormack Graduate School

of Policy & Global Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston, 100 Morrissey Blvd., Boston, MA 02125. E-mail: Corina.

Ronneberg@gmail.com

Received October 29 2013; Accepted June 3 2014.

Decision Editor: Rachel Pruchno, PhD

Purpose of the Study: Approximately 20% of older adults are diagnosed with depression

in the United States. Extant research suggests that engagement in religious activity, or

religiosity, may serve as a protective factor against depression. This prospective study

examines whether religiosity protects against depression and/or aids in recovery.

Design and Methods: Study data are drawn from the 2006 and 2008 waves of the Health

and Retirement Study. The sample consists of 1,992 depressed and 5,740 nondepressed

older adults (mean age = 68.12 years), at baseline (2006), for an overall sample size

of 7,732. Logistic regressions analyzed the relationship between organizational (service

attendance), nonorganizational (private prayer), and intrinsic measures of religiosity and

depression onset (in the baseline nondepressed group) and depression recovery (in the

baseline depressed group) at follow-up (2008), controlling for other baseline factors.

Results: Religiosity was found to both protect against and help individuals recover from

depression. Individuals not depressed at baseline remained nondepressed 2years later

if they frequently attended religious services, whereas those depressed at baseline were

less likely to be depressed at follow-up if they more frequently engaged in private prayer.

Implications: Findings suggest that both organizational and nonorganizational forms of

religiosity affect depression outcomes in different circumstances (i.e., onset and recovery, respectively). Important strategies to prevent and relieve depression among older

adults may include improving access and transportation to places of worship among

those interested in attending services and facilitating discussions about religious activities and beliefs with clinicians.

Key words: Organizational religiosity, Public religiosity, Nonorganizational religiosity, Private religiosity, Intrinsic

religiosity, Religion, Social support, Mental health

Depression is a major concern in the United States, as

more than 5% of the general population over 12years old

reports being depressed at any given time (Pratt & Brody,

2008). The prevalence of depression becomes even more

alarming at older ages as 20% of those 65years and older

report being depressed (Hurst, Williams, King, & Viken,

The Author 2014. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of The Gerontological Society of America. All rights reserved.

For permissions, please e-mail: journals.permissions@oup.com.

Page 1 of 12

The Gerontologist, 2014, Vol. 00, No. 00

sizes also tend to be small and focus exclusively on, for

example, the effects of religiosity on depression recovery,

rather than both depression onset and recovery (Bosworth,

Park, McQuoid, Hays, & Steffens, 2003; Hayward etal.,

2012; Koenig etal., 1998). There is a lack of consistency

in measurement as well, with one or more religiosity measures tending to be employed operationalizing such concepts

as organizational religiosity, nonorganizational religiosity,

intrinsic religiosity, religious salience, religious affiliation,

religious orthodoxy, and religious coping, though indicators of the former three domains are most commonly used

(Blay etal., 2008; Bosworth etal., 2003; Braam, Beekman,

Deeg, Smit, & Tilburh, 1997; Braam etal., 2004; Branco,

2000; Hayward et al., 2012; Idler & Kasl, 1992; King etal.,

2007; Koenig et al., 1997, 1998; Levin, 2010; Schnittker,

2001; Sun etal., 2012).

The primary goals of this study are to assess depression levels both at baseline and 2 years later, in order to

determine (a) whether religiosity protects against depression and (b) whether religiosity aids in the recovery from

depression. Shortcomings in extant research are addressed

in several ways. First, we use a larger, more representative

sample than the previous work, focusing expressly on older

adults (residing in the United States), and employ a longitudinal perspective. Second, we employ a comprehensive

set of religiosity indicators, including organizational, nonorganizational, and intrinsic measures, as well as religious

salience, affiliation, and presence of both friends and relatives at ones place of worship.

Religiosity, Depression, and OlderAdults

The biopsychosocial diathesis-stress model of depression

(BPDS) posits that there are certain interconnected biological, psychological, and social factors that can affect an

individuals predisposition to depression (Schotte, Bossche,

Doncker, Claes, & Cosyns, 2006; Stein, 2005). These

include risk factors that can serve both as potential precursors of depression and potential protective factors that

can act as buffers against depression. Some individuals are

more vulnerable to depression due to biological factors

(e.g., age and gender), somatic factors (e.g., health status,

chronic conditions, disability, or recent medical setbacks),

psychological factors (e.g., mental illness and serious alcoholic use), and social influences (e.g., marital status, education, income, social support, volunteerism, and adverse

life events). In this study, religiosity is conceptualized as a

protective factor, which may help buffer against ones total

vulnerability for depression.

Religiosity typically refers not only to a belief in a higher

entity or something greater than oneself but also formal

involvement in organized religious activities and specific,

Downloaded from http://gerontologist.oxfordjournals.org/ at University Library, University of Illinois at Chicago on July 31, 2014

2008; Paukert et al., 2008). Because depression is one of

the most common mental health issues facing older adults

(Administration on Aging, 2012), the study of depression

and its correlates has become a priority among scholars

looking to improve the quality of life among this population (Administration on Aging, 2012).

Although conflicting results have been reported (e.g., positive, negative, or no relationship), recent investigations suggest

that involvement in religious activity may serve as a protective

factor against depression (Blay, Batista, Andreoli, & Gastal,

2008; Blazer, 2010; Hayward, Owen, Koenig, Steffens, &

Payne, 2012; King et al., 2007; Koenig, 2007, 2009; Law

& Sbarra, 2009; Smith, McCullough, & Poll, 2003). These

investigations also suggest that individuals who are more

religious may not only be more likely to recover from certain ailments such as acute myocardial infarction (Martin &

Levy, 2006) and severe mental illness (Webb, Charbonneau,

McCann, & Gayle, 2011), but do so more quickly, while

experiencing shorter hospitalization stays (Contrada et al.,

2004). Together, these findings suggest a potentially important avenue for preventing and/or promoting recovery from

depression, especially given the large role that religion plays

in the lives of most Americans, 90% of whom report believing in God or a universal spirit (Gallup, 2013) and 90% of

whom report engaging in prayer (Hill etal., 2000).

The role that religion plays in peoples lives becomes

more pronounced with age. One national survey, for

example, found that nearly 70% of adults 50 years or

older reported that religion is very important in their lives

compared with 44% of adults under 30years old (Cohen

& Koenig, 2003). Older adults also exhibit higher levels

of religiosity or actual involvement in religious activities

(Boswell, Kahana, & Dilworth-Anderson, 2006). The fact

that religiosity appears to increase with age coupled with

the high prevalence of depression among older adults suggests the need to further study the effects of religious beliefs

and activities on depression among the elderly.

The need to further study the effects of religiosity on

depression is also suggested by current research. Most existing research in this area has been cross-sectional (Blay etal.,

2008; Branco, 2000; Lawler-Row & Elliott, 2009; Waddell

& Jacobs-Lawson, 2010; Yohannes, Koenig, Baldwin, &

Connolly, 2008). That which is longitudinal has focused on

limited population subsets (e.g., African Americans elders

and adolescents with psychiatric conditions) (Dew et al.,

2010; Ellison & Flannelly, 2009), local or regional populations (Idler & Kasl, 1992; King etal., 2007; Koenig etal.,

1997; Koenig, George, & Peterson, 1998; Sun etal., 2012),

and non-U.S. samples (e.g., Australian, Lebanese, Israeli,

European elders, or Brazilian) (Braam etal., 2001; Chaaya,

Sibai, Fayad, & El-Roueiheb, 2007; Iecovich, 2001; Law &

Sbarra, 2009; Payman, George, & Ryburn, 2008). Sample

Page 2 of 12

The Gerontologist, 2014, Vol. 00, No. 00

Page 3 of 12

between nonorganizational religiosity and depression

cross-sectionally, but a U-shaped association longitudinally

(King etal., 2007). Yet another study found nonorganizational religiosity to be associated with lower depression

severity after 3 months (Hayward et al., 2012). Findings

around intrinsic religiosity are also inconsistent. Parker and

coworkers (2003) found no relationship between intrinsic

religiosity and depression, King and coworkers (2007) a

positive relationship, and Koenig and coworkers (1998)

quicker remission from depression.

Evidence suggests that the impact of religiosity on depression is stronger among women who also tend to be more

active participants in both organizational and nonorganizational religious activities than men, including, for example, religious affiliation and private prayer (Wink & Dillon,

2002; Yohannes etal., 2008). This tendency is reflected in

a 2002 Health and Retirement Study (HRS) of older adults

60 years or older, which found higher ratings of religious

importance to be a protective factor against depression in

womenbut not men (Waddell & Jacobs-Lawson, 2010).

Based on previous research and according to the BPDS

model of depression, this study hypothesizes that (a)

higher religiosity will be associated with a lower likelihood

of depression 2 years later among older adults without

depression at baseline (i.e., religiosity will protect against

depression onset) and (b) higher religiosity will be associated with a lower likelihood of depression 2years later for

respondents depressed at baseline (i.e., religiosity will aid in

depression recovery).

Methods

DataSource

The sample in this study was drawn from the 2006 and

2008 waves of the HRS; the goal was to model depression in 2008 based on respondent characteristics in 2006.

The HRS is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging

(grant number NIA U01AG009740) and is conducted by

the University of Michigan (Health and Retirement Study,

2006/2008). The HRS began collecting data in 1992 and

continues to do so every 2years. The HRS is a nationally

representative study that contains rich information on

more than 22,000 community-dwelling older adults aged

50 or older, with respect to respondent health, functional

status, cognition, living arrangements, retirement, religious

affiliation, and involvement in assorted activities.

Sample

The sample utilized in this study includes the subset of

HRS respondents who completed the 2006 Leave-Behind

Questionnaire (n = 7,732). The rationale for utilizing the

Downloaded from http://gerontologist.oxfordjournals.org/ at University Library, University of Illinois at Chicago on July 31, 2014

measurable acts such as prayer, meditation, service attendance, religious readings, and affiliation with a particular religion or place of worship (Hill etal., 2000; Iecovich, 2001;

Yohannes etal., 2008). Akey characteristic of religion is that

it is organized in a hierarchical fashion with an identified

authority figure such as a priest, pastor, or rabbi presiding.

Although religion refers to someones belief system, religiosity is the actual application of such beliefs in dailylife.

The literature distinguishes between three general types

of religiosity: organizational, nonorganizational, and intrinsic. Organizational religiosity typically involves public or

group activities and is most commonly measured by ones

religious service attendance (Koenig etal., 1998; Sun etal.,

2012). Nonorganizational religiosity, by contrast, is more

private and typically occurs on a persons own time, alone,

encompassing activities such as reading religious texts,

praying, and/or meditating (Koenig etal., 1998; Sun etal.,

2012). Intrinsic religiosity is concerned with individuals

subjective meaning of religiosity and how religious beliefs

affect everyday life (Sun etal., 2012). Studies have shown

that as individuals age, they are more likely to engage in

nonorganizational activities as opposed to organizational

modes of religious expression (Yohannes etal., 2008), possibly shifting to more private religious activities, perhaps

due to physical decline, rather than giving up on religious

involvement altogether.

Nearly 75% of older people who suffer from depression or anxiety partake in some kind of religious activity at

least monthly (Paukert etal., 2009). Ameta-analysis of 147

studies found higher religiosity to be associated with fewer

depressive symptoms or indicators in more than three quarters of the studies analyzed (Smith etal., 2003). Furthermore,

individuals who regularly attend religious services display

lower rates of depression when compared with individuals who either do not attend services or do attend services

but on a more sporadic basis (Blazer, 2010; Braam et al.,

2004; Koenig etal., 1997). In a prospective study focusing

on African Americans over the age of 55, it was found that

individuals who received guidance from their religion on a

regular basis were less likely to suffer from major depression

34years later (Ellison & Flannelly, 2009).

Extant research also demonstrates that religious involvement may benefit clinically depressed individuals (Koenig

etal., 1998; Murphy & Fitchett, 2009). Depressive symptoms have been shown to decrease across time in persons

engaged in organizational religiosity (Braam et al., 2004;

Koenig, 2007; Law & Sbarra, 2009; Levin, 2010; Smith

et al., 2003). However, mixed results abound regarding

nonorganizational modes of religious involvement. For

instance, one cross-sectional study found nonorganizational religiosity unrelated to depression (Koenig et al.,

1997), whereas another found an inverse relationship

The Gerontologist, 2014, Vol. 00, No. 00

Leave-Behind Questionnaire is that it contains much more

comprehensive measures of religiosity than the basic HRS

survey. In all, 944, or 12% of respondents, were missing

information on at least one HRS item. Thus, for purposes

of our analyses, we employed multiple imputation of missing data to fill in the missing values. Twenty imputations

were conducted and pooled results were used in the analyses reported.

Dependent Variable (Depression)

Depression status (in 2008) is the outcome variable in

the present study. Depression is assessed with Center for

Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CESD-8). The

presence of three or more symptoms, out of eight, indicates

a higher likelihood of being clinically depressed (Steffick,

2000). Therefore, respondents reporting three or more

depressive symptoms were coded 1=depressed; those with

zero, one, or two symptoms as 0=not depressed.

Independent Variables (Religiosity)

Five religiosity questions are asked in the basic HRS.

Religious affiliation was self-reported as Protestant,

Catholic, Jewish, or none/other religion. Respondents were

asked about organizational religiosity, via the frequency

of attendance at religious services: high (more than once

a week or once a week), moderate (two to three times a

month), and low/none (one or more times a year or not at

all). Additionally, respondents were asked about the presence of both friends and relatives in ones congregation (yes

or no). Lastly, respondents were asked to rate the importance of religiosity: very, somewhat, or not important.

Each of these items was coded as a series of dichotomous

variables.

The Leave-Behind Questionnaire includes two additional measures of religiosity. The first is an index of

religiosity, an intrinsic measure, composed of four items

( = .92)believe God watches over me, events unfold

according to a divine/greater plan, carry religious beliefs

into all dealings in life, find strength and comfort in religion. Possible scores range from 1 (strongly disagree) to

6 (strongly agree) (averaged across the four items) where

higher scores indicate higher religiosity levels. The second

Leave-Behind Questionnaire item measured the frequency

of prayer in private contexts, a nonorganizational measure. The scores (18) on this item were reverse coded

so that higher scores denote higher frequency of private

prayer.

The potential for multicollinearity was examined

in several ways. Neither variance inflation factors

(all<4.5) nor correlations (all < 0.62) among the seven

religiosity measures revealed problematic multicollinearity. Moreover, each of the seven religiosity variables

was entered one by one into the model and as a block,

both with and without covariates, both for the depressed

and nondepressed samples. Results on the religiosity

variables largely remained consistent across these various specifications. The final model therefore includes all

seven religiosity variables described previously along

with covariates.

Covariates

This study controls for biological, somatic, psychological, and social factors that have been found to be associated with depression. Prior research suggests that older

adults, females, and non-Hispanic Blacks exhibit higher

rates of depression compared with their younger, male,

and white counterparts (Law & Sbarra, 2009; Pratt &

Brody, 2008). Age is measured as a continuous variable (number of years); gender as a dichotomous variable, with female = 1 and male = 0; and race/ethnicity

as a series of dichotomous variables for white, black,

Hispanic, andother.

In addition, somatic or health conditions may be

related to depression status (Blazer, 2010; Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention, 2011a; Koenig, 1999; Lo

etal., 2010; Schotte etal., 2006). At baseline, respondents

were asked whether they had ever been diagnosed with

each of seven chronic ailments: high blood pressure, diabetes, cancer, lung disease, heart conditions, stroke, and

arthritis. The number of chronic conditions was summed

(07) with a higher count indicating greater comorbidity.

Respondents were also asked whether they had recently

experienced each of three somatic life events in the last

two years (since baseline): stroke, heart attack, and/or

cancer. It is important to account for the onset of illnesses

such as these, as recently experiencing a negative event has

been found to be associated with depression (Schnittker,

2001). A count (03) of somatic events was developed,

with a higher number indicating greater comorbidity.

Self-reported health status was measured using a series

of dichotomous indicator variables: excellent, very good,

good, fair, or poor. Functional limitations were measured

using counts of both instrumental activities of daily living

(IADLs) (06) and basic activities of daily living (ADLs)

(05).

Alcohol abuse appears to be associated with depression (Blay et al., 2008; Braam et al., 2004; Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011a; Idler &

Kasl, 1992; Rodriguez, Schonfeld, King-Kallimanis, &

Amber, 2010). Consistent with previous research (Satre,

Gordon, & Weisner, 2007), respondents were identified

as a serious drinker, or abuser of alcohol, if they were

Downloaded from http://gerontologist.oxfordjournals.org/ at University Library, University of Illinois at Chicago on July 31, 2014

Measurement

Page 4 of 12

The Gerontologist, 2014, Vol. 00, No. 00

Page 5 of 12

AnalyticalPlan

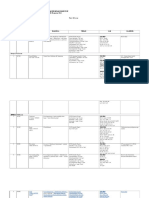

Basic descriptive statistics are reported, followed by bivariate analyses comparing the baseline characteristics of the

depressed and nondepressed samples (Table 1). Results

from multivariate analyses are presented next, utilizing logistic regression to model the relationship between

depression and religiosity, controlling for other baseline

factors. Two logistic regressions models were employed:

one with baseline depressed respondents and the second

with baseline nondepressed respondents (Table2).

Results

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics for the entire sample, as well as differentiated by depression status in 2006.

Depressed and nondepressed samples had similar religious

affiliations (2=3.94 (3), p > .05). At 45% and 37%, respectively, high frequency of religious service attendance was

more likely to be reported by nondepressed than depressed

respondents, whereas depressed respondents were more

likely to report low or no service attendance than their nondepressed counterparts (51% vs. 43%) (2 = 43.19 (2), p

< .001). Ahigher proportion of nondepressed respondents

(59%) reported having friends at their congregation than

depressed respondents (50%) (2 = 44.42 (1), p < .001);

approximately one quarter of each group reported sharing their congregation with family (2=0.01 (1), p > .05).

There was a small but significant difference assigned to the

importance of religion, with depressed respondents being

Table1. Descriptive and Bivariate Statistics for Baseline (2006) Depressed and Nondepressed Samples

Covariates

Religiosity factors

Religiosity (basic HRS questions)

Religious affiliation

Protestant

Catholica

Jewish

None/other

Service attendance

High

Moderatea

Low/none

Friends in congregation

Relatives in congregation

Importance of religion

Very important

Somewhat important

Not importanta

Entire sample (n=7,732)

Depressed (n=1,992)

Nondepressed (n=5,740)

# (%)/mean (SD)

# (%)/mean (SD)

# (%)/mean (SD)

4,892 (63.3%)

2,048 (26.5%)

158 (2.0%)

614 (7.9%)

1,276 (64.1%)

501 (25.2%)

48 (2.4%)

162 (8.1%)

3,616 (70.0%)

1,547 (27.0%)

110 (1.9%)

452 (7.9)

3,324 (43.0%)

917 (11.9%)

3,493 (45.2%)

4,367 (56.5%)

1,891 (24.5%)

740 (37.2%)

232 (11.7%)

1,021 (51.3%)

998 (50.1%)

489 (26.6%)

2,584 (45.0%)

685 (12.0%)

2,472 (43.1%)

3,369 (58.7%)

1,402 (24.4%)

5,273 (68.2%)

1,591 (20.6%)

871 (11.3%)

1,390 (69.8%)

422 (21.2%)

183 (9.2%)

3,883 (67.7%)

1,170 (20.4%)

688 (12.0%)

2(df)/t

3.94 (3)

43.19 (2)***

44.42 (1)***

0.01 (1)

10.60 (2)**

Downloaded from http://gerontologist.oxfordjournals.org/ at University Library, University of Illinois at Chicago on July 31, 2014

(a) a woman that consumes more than two drinks per

occasion or (b) a man that consumes more than three

drinks per occasion. Also included is a dichotomous

variable indicating whether or not an individual had

ever been diagnosed with any emotional or psychiatric

condition(s) (Koenig et al., 1998). Both variables have

been shown to increase the risk for, or coexist with,

depression (Aina & Suman, 2006; Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention, 2011b) and have been used as

covariates in similar studies.

Social factors have the potential to predispose individuals toward depression (Schotte etal., 2006). The influences

of social and economic considerations are reflected, in part,

in sociodemographic variables, including marital status

(married, divorced/separated, widowed, or never married),

education (in years), and household income (in quartile

earnings). Social considerations are also reflected, in part,

in living alone, volunteerism, and having family and friends

nearby. Certain recent adverse life events such as serious

losses, threatening occurrences, or difficulties in life are

also predictive of depression (Schnittker, 2001; Schotte

et al., 2006, p. 314). These include experiencing divorce/

separation, death of a spouse/partner, a nursing home stay,

and residential move in the last 2years. Acount has been

created (04), where a higher number indicates experiencing more recent adverse social events. Lastly, whether

respondents were living in a nursing home as opposed to a

community setting at the time of the survey was recorded,

in addition to whether survey responses were provided by

a proxy or not.

The Gerontologist, 2014, Vol. 00, No. 00

Page 6 of 12

Table1. Continued

Covariates

Depressed (n=1,992)

Nondepressed (n=5,740)

# (%)/mean (SD)

# (%)/mean (SD)

# (%)/mean (SD)

2(df)/t

4.99 (1.39)

6.11 (2.32)

5.02 (1.33)

6.25 (2.26)

4.98 (1.40)

6.06 (2.34)

1.26

3.17**

68.11 (1.39)

4,543 (58.8%)

68.80 (11.44)

1,317 (66.1%)

67.87 (10.40)

3,226 (56.2%)

3.19***

59.96 (1)***

6,009 (77.7%)

1,004 (13.0%)

601 (7.7%)

118 (1.5%)

1,462 (73.4%)

292 (14.8%)

204 (10.2%)

34 (1.7%)

4,547 (79.2%)

712 (12.4%)

397 (6.9%)

84 (1.5%)

33.84 (3)***

1.92 (1.33)

2.39 (1.37)

1.75 (1.27)

18.46***

904 (11.7%)

2,350 (30.4%)

2,395 (31.0%)

1,554 (20.1%)

543 (7.0%)

0.34 (.82)

0.34 (.94)

0.07 (0.27)

70 (3.5%)

310 (15.6%)

547 (27.5%)

702 (35.2%)

369 (18.5%)

0.63 (1.07)

0.80 (1.38)

0.09 (0.30)

834 (14.5%)

2,040 (35.5%)

1,848 (32.2%)

851 (14.8%)

174 (3.0%)

0.24 (0.70)

0.18 (0.66)

0.07 (0.26)

1174.17 (4)***

351 (4.5%)

1,244 (16.1%)

101 (5.2%)

655 (32.9%)

250 (4.4%)

589 (10.3%)

1.74 (1)

558.35 (1)***

5,039 (65.2%)

966 (12.5%)

1,504 (19.5%)

223 (2.9%)

12.58 (3.11)

1,029 (51.7%)

342 (17.2%)

542 (27.2%)

79 (4.0%)

11.78 (3.30)

4,010 (70.0%)

624 (10.9%)

962 (16.8%)

144 (2.5%)

12.86 (2.99)

216.04 (3)***

1,747 (22.6%)

1,922 (25.4%)

1,985 (25.7%)

2,078 (26.9%)

0.12 (0.12)

722 (36.2%)

528 (26.5%)

391 (19.6%)

351 (17.6%)

0.12 (0.33)

1,025 (17.9%)

1,394 (24.3%)

1,594 (27.8%)

1,727 (30.1%)

0.12 (0.33)

347.93 (3)***

1,673 (21.6%)

2,786 (36.0%)

2,157 (27.9%)

5,026 (65.0%)

283 (3.7%)

99 (1.3%)

614 (30.8%)

475 (23.8%)

577 (29.0%)

1,241 (62.3%)

63 (3.2%)

48 (2.4%)

1,059 (18.4%)

2,311 (40.2%)

1,580 (27.5%)

3,784 (70.0%)

220 (3.8%)

52 (0.9%)

133.54 (1)***

172.90 (1)***

0.94 (1)

11.80 (1)***

1.88 (1)

18.96 (1)***

15.01***

19.48***

2.73**

13.53***

0.45

Notes: ADLs=activities of daily living; HRS=Health and Retirement Study; IADLs=instrumental activities of daily living; LBQ=Leave-Behind Questionnaire.

a

Denotes reference groups.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Downloaded from http://gerontologist.oxfordjournals.org/ at University Library, University of Illinois at Chicago on July 31, 2014

Religiosity (LBQ)

Index of religiosity

Frequency private prayer

Biological variables

Demographic variables

Age

Female

Race/ethnicity

Whitea

Black

Hispanic

Other

Somatic variables

Health and functional limitation

Chronic conditions

Self-reported health

Excellent

Very good

Gooda

Fair

Poor

IADLs

ADLs

Somatic adverse life events

Psychological variables

High alcohol use

Psychological issues

Social variables

Sociodemographic variables

Marital status

Marrieda

Divorced/separated

Widowed

Never married

Education level

Household income

Quartile 1a

Quartile 2

Quartile 3

Quartile 4

Social adverse life events

Social support variables

Living alone

Volunteer status

Relatives live near

Friends live near

Have proxy respondent

Live in nursing home

Entire sample (n=7,732)

The Gerontologist, 2014, Vol. 00, No. 00

Page 7 of 12

Table2. Logistic Regressions Modeling the Relationship Between Follow-Up (2008) Depression and Religiosity and Other

Covariates Among Baseline (2006) Depressed and Nondepressed Samples

Covariates

Nondepressed at baseline

(n=5,740)

Odds ratio

p value

Odds ratio

p value

0.91

2.05

0.907

0.465

0.040*

0.644

1.03

1.30

1.19

0.768

0.382

0.325

1.36

1.18

0.92

1.13

0.062

0.330

0.498

0.336

0.65

0.75

0.95

0.92

0.001***

0.035*

0.659

0.432

0.81

1.00

0.332

0.995

1.23

1.01

0.275

0.977

1.10

0.93

0.052

0.015*

1.00

0.98

0.949

0.476

0.99

1.174

0.099

0.513

1.00

1.44

0.319

0.000***

0.81

0.95

1.04

0.158

0.785

0.971

0.873

1.02

0.67

0.304

0.889

0.304

1.06

0.127

1.09

0.020*

0.43

0.80

1.32

1.33

1.03

1.04

1.57

0.004**

0.140

0.029*

0.086

0.640

0.412

0.008**

0.54

0.72

1.77

2.69

0.896

1.13

1.16

0.000***

0.002**

0.000***

0.000***

0.113

0.058

0.106

0.803

1.607

0.329

0.000***

1.03

1.93

0.877

0.000***

0.99

0.72

0.70

0.972

0.048*

0.197

0.88

0.88

0.62

0.407

0.390

0.103

Downloaded from http://gerontologist.oxfordjournals.org/ at University Library, University of Illinois at Chicago on July 31, 2014

Religiosity factors

General HRS religiosity items

Religious affiliation

Protestant

Catholica

Jewish

None/other

Frequency of attendance at religious services

High

Moderatea

Low/none

Friends in congregation

Relatives in congregation

Importance of religion

Very important

Somewhat important

Not importanta

Religiosity items (LBQ)

Index of religiosity

Frequency of private prayer

Biological variables

Demographic variables

Age

Female

Race/ethnicity

Whitea

Black

Hispanic

Other

Somatic variables

Health and functional limitation variables

Self-reported chronic conditions

Self-reported health

Excellent

Very good

Gooda

Fair

Poor

IADLs

ADLs

Somatic adverse life events

Psychological variables

Serious alcohol use

Psychological issues

Social variables

Sociodemographic variables

Marital status

Marrieda

Divorced/separated

Widowed

Never married

Depressed at baseline

(n=1,992)

The Gerontologist, 2014, Vol. 00, No. 00

Page 8 of 12

Table2. Continued

Covariates

Nondepressed at baseline

(n=5,740)

Odds ratio

p value

Odds ratio

p value

0.98

0.155

0.99

0.333

0.73

0.81

0.66

1.461

0.017*

0.189

0.023*

0.011*

0.93

0.82

0.69

1.42

0.528

0.143

0.017*

0.002**

1.12

0.421

1.16

0.227

1.31

0.018*

0.954

0.659

0.000

1.000

0.411

0.049*

2 log likelihood: 1941.1***

1.35

0.035*

0.90

0.275

1.23

0.025*

0.91

0.291

0.236

0.000***

0.741

0.538

2 log likelihood: 3648.2***

Notes: ADLs=activities of daily living; HRS=Health and Retirement Study; IADLs=instrumental activities of daily living; LBQ=Leave-Behind Questionnaire.

a

Denotes reference groups.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

more likely to report very important (70% vs. 68%)

and depressed respondents being less likely to report not

important (9% vs. 12%) (2 = 10.60 (2), p < .01). No

significant difference could be discerned between the two

groups on the religiosity index (t=1.26, p > .05), but there

was a significant difference in regard to the frequency of private prayer (t=3.17, p < .01) with depressed respondents

reporting higher frequency (6.25 vs. 6.06 [out of8]).

Significant differences could also be discerned with

respect to all covariates but high alcohol use (2=1.74 (1),

p > .05), social adverse life events (r=.45, p > .05), the presence of relatives living nearby (2=0.94 (1), p > .05), and

having a proxy respondent (2=1.88 (1), p > .05). Thus,

nondepressed respondents were more likely than depressed

respondents to be younger (r = 3.19, p < .001), male

(2=59.96, p < .001), non-Hispanic white (2=33.84, p <

.001), in excellent very good/good health (2=1174.17, (4),

p < .001), married (2=216.04, p < .001), have higher education (t=13.53, p < .001), have higher income (2=347.93

(3), p < .001), volunteer (2=172.90, p < .001), and have

friends living nearby (2 = 11.80, p < .001). By contrast,

depressed respondents were more likely than nondepressed

respondents to be chronically ill (t = 18.46, p < .001),

IADL (t=15.01, p < .001) and ADL (t=19.48, p < .001)

impaired, suffer from adverse somatic life events (t=2.73,

p < .01), have psychological issues (2=558.35, p < .001),

live alone (2=133.54 (1), p < .001), or live in a nursing

home (2=18.96 (1), p <.001).

Two main logistic regression models were estimated. The

first model is composed of individuals who were depressed

at baseline (n=1,992) (Table2). Two religiosity variables

were significant. The odds of being depressed at follow-up

were two times higher among depressed respondents with

a Jewish affiliation (odds ratio [OR]=2.05, p < .05) but

lower for those with more frequent engagement in private

prayer (OR=0.93, p <.05).

The first model also indicates that depressed individuals

who were in excellent health (OR = 0.43, p < .01), widowed (OR=0.72, p < .05), had higher household income

(OR = 0.73, p < .05; OR = 0.66, p < .05), or who lived

in a nursing home (OR=0.41, p < .05) had a decreased

likelihood of being depressed at follow-up. In contrast,

depressed persons who reported more somatic life events

(OR=1.57, p < .01), had psychological issues (OR=1.61,

p < .001), reported more social adverse life events

(OR = 1.46, p < .05), and lived closer to their relatives

(OR=1.31, p < .05) were more likely to remain depressed

2yearslater.

The second model is composed of individuals who were

not depressed at baseline (n = 5,740) (Table 2). Service

attendance was the only religiosity variable to prove significant. In particular, nondepressed respondents with high

service attendance were 35% less likely to be depressed

at follow-up (OR = 0.65, p < .01), and respondents with

low/no service attendance were 25% less likely to become

depressed (OR=0.75, p < .05), in comparison to those with

Downloaded from http://gerontologist.oxfordjournals.org/ at University Library, University of Illinois at Chicago on July 31, 2014

Education level

Household income

Quartile 1a

Quartile 2

Quartile 3

Quartile 4

Social adverse life events

Social support variables

Living alone

Volunteer status

Relatives live near

Friends live near

Have proxy respondent

Live in a nursing home

Depressed at baseline

(n=1,992)

Page 9 of 12

Discussion

This study sought to understand whether religiosity (a)

protects against future depression and (b) plays a role in

depression recovery, among older adults. Consistent with

prior research (Blazer, 2010; Koenig, 2007; Smith et al.,

2003), results provide evidence supporting both of these

expectations, though the specific aspect of religiosity found

to protect against depression (frequent service attendance)

was different from the component found to aid in depression recovery (private prayer frequency). Relative to those

with moderate service attendance, individuals who were

not depressed at baseline (in 2006)were less likely to be

depressed 2 years later if they frequently attended religious services. It was expected that high service attendance would protect against depression, perhaps due to the

availability, promotion, or benefits of social support found

in ones place of worship. In particular, the protective pathway stemming from service attendance may derive from

the comparatively higher levels of social capital resulting

from engagement in public modes of behavior, specifically

the interpersonal relationships formed and sustained by

active participation in a religious congregation. The presence of more social connections, in turn, may reduce the

likelihood of isolation and loneliness, two factors associated with depression.

Counterintuitively, individuals with low service attendance who were not depressed at baseline were also less

likely to be depressed 2 years later relative to those with

moderate service attendance. It is possible that persons

with low or no service attendance may be less likely to

be depressed at follow-up because they are more likely to

engage in other, less public forms of religiosity that, in turn,

provide protective benefits from depression and other ailments. That this may be the case is suggested by the moderate, significant inverse correlation between private prayer

frequency and level of service attendance (r = .496, p <

.05). Thus, whereas the high service attendance group may

be disproportionately devoted to organizational forms of

religiosity, the low service attendance group may be disproportionately devoted to nonorganizational forms. In

contrast, the moderate service attendance group may not

be disproportionately devoted to either form of religious

behavior and, as such, may be less likely to experience the

benefits that derive fromeach.

Consistent with expectations, persons who started

out depressed at baseline were less likely to be depressed

2 years later if they more frequently engaged in private

prayer. This finding suggests that persons who become

depressed may turn to their faith for support and as a

means of coping from adverse life eventsfinancial,

health, social, or otherwise. Subsequent engagement in

private prayer may serve, in part, to cultivate hope for

the future, potentially activating cognitive resources that

eventually counter depression.

Interestingly, Jewish respondents were much more likely

to remain depressed at follow-up than other respondents.

One possible explanation for this finding could be the

long-term, negative implications that belonging to a religious minority has on mental health (Berger, 1977). This

may be particularly important for the population surveyed

because anti-Semitism was much more visible and prevalent during our respondents formative years than it is

today. Another possible explanation could be that Jewish

elders may not benefit in the same way from religious

involvement as members of other religious affiliations.

Take Christian doctrine, for example, which emphasizes

the afterlife or Heaven at which point the body may be

restored and a reunion takes place with long deceased

loved ones (Gillman, 2007). This belief can be great source

of solace, hope, and comfort for those going through hard

times (e.g., depression), which may, in turn, support coping and recovery. This is in contrast to Jewish doctrine,

which in downplaying the hereafter in favor of the here

and now, may not provide the same level of solace, hope,

and comfort (Gillman, 2007).

One interesting yet surprising finding emerging from

this study is that having relatives living nearby was associated with depression at follow-up among both the baseline

depressed and nondepressed samples analyzed. It is plausible that there are certain unwanted expectations inherent

when family members live closerwhether, for example,

caring for a frail and disabled parent or other relative in

need of long-term care or watching a young grandchild

in need of after school care, that results in burdens and

stresses that might not otherwise exist if family lived further away. Simply measuring proximity, moreover, does

not account for the frequency or quality of the interactions

that take place. For example, some relationships, even with

relatives, may not be pursued no matter how convenient, if

those relationships are not fulfilling.

Downloaded from http://gerontologist.oxfordjournals.org/ at University Library, University of Illinois at Chicago on July 31, 2014

moderate service attendance. Other factors associated with

increased likelihood of depression onset included female

gender (OR=1.44, p < .001), chronic illness (OR=1.09,

p < .05), fair or poor health (OR=1.77, OR=2.69, both

p < .001), psychological issues (OR = 1.93, p < .001),

adverse social events (OR = 1.42, p < .01), living alone

(OR = 1.35, p < .05), and having relatives live nearby

(OR=1.23, p < .05). By contrast, factors that appeared to

guard against depression onset included reporting excellent

or very good health (OR=0.54, p < .001; OR=0.72, p

< .01), higher income (OR=0.69, p < .05), and having a

proxy respondent (OR=0.24, p < .001).

The Gerontologist, 2014, Vol. 00, No. 00

The Gerontologist, 2014, Vol. 00, No. 00

Conclusion

Several implications for policy and practice follow from

the results of this study. One is related to transportation

availability and the provision of better access to places of

worship so that older adults who are interested in religious

services are able to attend and subsequently benefit from

organizational, or public, forms of religiosity. Moreover,

given the high prevalence of depression among older

adults, clinicians should be cognizant of the benefits associated with both religious service attendance and involvement in private prayer, assess individuals religious needs

and involvement, and determine whether their clients face

any barriers to attending services or pursuing their faith if

they so desire. Through these assessments, clinicians could

help connect interested clients to such services within their

communities or help them overcome any barriers they may

be experiencing, hindering involvement private prayer. Care

plans or therapy goals can be developed, which address

these issues as well.

References

Administration on Aging. (2012). Older Americans behavioral health. Retrieved from http://www.aoa.gov/AoARoot/

AoA_Programs/HPW/Behavioral/docs2/Issue%20Brief%20

Series%20Overview.pdf

Aina, Y., & Suman, J. L. (2006). Understanding comorbidity with

depression and anxiety disorders. Journal of the American

Osteopathic Association, 106, S9S14. Retrieved from http://

www.jaoa.org/content/106/5_suppl_2/S9.full.pdf

Berger, D. M. (1977). The survivor syndrome: Aproblem of nosology and treatment. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 31,

238251. Retrieved from http://www.ajp.org

Blay, S. L., Batista, A. D., Andreoli, S. B., & Gastal, F. L. (2008). The

relationship between religiosity and tobacco, alcohol use, and

depression in the elderly community population. The American

Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16, 934943. doi:10.1097/

JGP.0b013e3181871392

Blazer, D. G. (2010). The origins of late-life depression. Psychiatric

Annals, 40, 1318. doi:10.3928/00485718-20091229-01

Boswell, G. H., Kahana, E., & Dilworth-Anderson, P. (2006).

Spirituality and healthy lifestyle behaviors: Stress counter-balancing effects on the well-being of older adults. Journal of Religion

and Health, 45, 587602. doi:10.1007/s10943-006-9060-7

Bosworth, H. B., Park, K. S., McQuoid, D. R., Hays, J. C., & Steffens,

D. C. (2003). The impact of religious practice and religious coping on geriatric depression. International Journal of Geriatric

Psychiatry, 18, 905914. doi:10.1002/gps.945

Braam, A. W., Beekman, A. T.F., Deeg, J. J.H., Smit, J. H., & Tilburh,

W. V. (1997). Religiosity as a protective or prognostic factor of

depression in later life; Results from a community survey in

The Netherlands. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia, 96, 199205.

doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb10151.x

Braam, A. W., Hein, E., Deeg, D. J.H., Twisk, J. W.R., Beekman, A.

T.F., & Tilburg, W. V. (2004). Religious involvement and 6-year

course of depressive symptoms in older Dutch citizens: Results

from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. Journal of Aging

and Health, 16, 467489. doi:10.1177/0898264304265765

Braam, A. W., Van Den Eeden, P., Prince, M. J., Beekman, A. T.F.,

Kivela, S. L., Lawlor, B. A., Copeland, J. R. M. (2001).

Religion as a cross-cultural determinant of depression in

elderly Europeans: Results from the EURODEP collaboration. Psychological Medicine, 31, 803814. doi:http://dx.doi.

org/10.1017/S0033291701003956

Branco, K. J. (2000). Religiosity and depression among nursing home

residents: Results of a survey of ten states. Journal of Religious

Gerontology, 12, 4361. doi:10.1300/J078v12n01_05

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011a). Mental health

basics. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/basics.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011b). Depression.

Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/basics/mentalillness/depression.htm

Downloaded from http://gerontologist.oxfordjournals.org/ at University Library, University of Illinois at Chicago on July 31, 2014

There are several limitations worth noting. First, depression is measured using the CESD-8, a self-report tool,

rather than using the clinical diagnosis of depression by a

health or mental health professional. Although the latter

may be the gold standard, the CESD-8 is a commonly used

and accepted measure of depression in studies such as this

one where clinical diagnosis was not possible (e.g., Steffick,

2000). Second, data from the CESD-8 were not utilized to

develop a measure of depression based on a continuous

count of depressive symptoms but instead used to place

individuals into depressed or nondepressed categories based

on the presence of three or more of the eight symptoms

assessed. One implication is that potentially useful variation may have been missing. This cutoff approach, however, is typically employed in studies utilizing the CESD-8

(Steffick, 2000). Athird limitation is related to the length of

the study. Given the episodic nature of depression, a 2-year

longitudinal study may miss signs of depression occurring after the time period analyzed. Future research should

extend the follow-up period studied over a longer period

of time as additional waves of the HRS become available.

Last, the Health and Retirement Study only includes measures of religiosity but not spirituality. Thus, this study is

focused exclusively on the former but not the latter. This

limitation is important to point out because extant research

suggests that spirituality may be associated with lower

rates of depression and mental illness as well (Skarupski,

Fitchett, Evans, & Mendes de Leon, 2010). Moreover, a

growing body of research suggests that spirituality to be a

unique construct, though related to religiosity (Underwood

& Teresi, 2002). Beyond this understanding experts hold

differing views regarding the distinction between religiosity

and spirituality, some maintaining that religiosity may be a

part of spirituality, whereas others viewing spirituality as a

part of religiosity (Hill etal., 2000; MacKinlay, 2006).

Page 10 of 12

Page 11 of 12

Koenig, H. G. (2007). Spirituality and depression: Alook at the evidence. Southern Medical Journal, 100, 737739. doi:10.1097/

SMJ.0b013e318073c68c

Koenig, H. G. (2009). Research on religion, spirituality, and mental

health: Areview. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 54, 283

291. Retrieved from http://publications.cpa-apc.org/browse/

documents/464

Koenig, H. G., George, L. K., & Peterson, B. L. (1998). Religiosity

and remission of depression in medically ill older patients.

American Journal of Psychiatry, 155, 536542. Retrieved from

http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/article.aspx?articleid=172792#A

bstract

Koenig, H. G., Hays, J. C., George, L. K., Blazer, D. G., Larson, D. B., &

Landerman, L. R. (1997). Modeling the cross-sectional relationships between religion, physical health, social support, and depressive symptoms. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 5,

131144. doi:10.1097/00019442-199700520-00006

Law, R. W., & Sbarra, D. A. (2009). The effects of church attendance

and marital status on the longitudinal trajectories of depressed

mood among older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 21,

803823. doi:10.1177/0898264309338300

Lawler-Row, K. A., & Elliott, J. (2009). The role of religious

activity and spirituality in the health and well-being of

older adults. Journal of Health Psychology, 14, 4352.

doi:10.1177/1359105308097944

Levin, J. (2010). Religion and mental health: Theory and research.

International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 7, 102

115. doi:10.1002/aps.240

Lo, C., Lin, J., Gagliese, L., Zimmermann, C., Mikulincer, M., &

Rodin, G. (2010). Age and depression in patients with metastatic cancer: The protective effects of attachment security and

spiritual wellbeing. Aging & Society, 30, 325336. doi:10.1017/

S0144686X09990201

MacKinlay, E. (2006). Spiritual care: Recognizing spiritual needs

of older adults. Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging, 18,

5971. doi:10.1300/J496v18n02_05

Martin, K. R., & Levy, B. R. (2006). Opposing trends of religious

attendance and religiosity in predicting elders functional recovery after an acute myocardial infarction. Journal of Religion &

Health, 45, 440451. doi:10.1007/s10943-006-9037-6

Murphy, P. E., & Fitchett, G. (2009). Belief in a concerned God predicts

response to treatment for adults with clinical depression. Journal

of Clinical Psychology, 65, 10001008. doi:10.1002/jclp.20598

Parker, M., Roff, L. L., Klemmack, D. L., Koenig, H. G., Baker, P., &

Allman, R. M. (2003). Religiosity and mental health in southern,

community-dwelling older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 7,

390397. doi:10.1080/1360786031000150667

Paukert, A. L., Phillips, L., Cully, J. A., Loboprabhu, S. M., Lomax,

J. W., & Stanley, M. A. (2009). Integration of religion into cognitive-behavioral therapy for geriatric anxiety and depression.

Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 15, 103112. doi:10.1097/01.

pra.0000348363.88676.4d

Payman, V., George, K., & Ryburn, B. (2008). Religiosity of

elderly depressed inpatients. International Journal of Geriatric

Psychiatry, 23, 1621. doi:10.1002/gps.1827

Pratt, L. A., & Brody, D. J. (2008). Depression in the United States

Household Population, 20052006. Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19389321

Downloaded from http://gerontologist.oxfordjournals.org/ at University Library, University of Illinois at Chicago on July 31, 2014

Chaaya, M., Sibai A. M., Fayad, R., & El-Roueiheb, Z. (2007).

Religiosity and depression in older people: Evidence from underprivileged refugee and non-refugee communities in Lebanon. Aging

& Mental Health, 11, 3744. doi:10.1080/13607860600735812

Cohen, A. B., & Koenig, H. G. (2003). Religion, religiosity, and spirituality in the biopsychosocial model of health and ageing. Ageing

International, 28, 215241. doi:10.1007/s12126-002-1005-1

Contrada, R. J., Goyal, T. M., Cather, C., Rafalson, L., Idler,

E. L., & Krause, T. J. (2004). Psychosocial factors in outcomes of heart surgery: The impact of religious involvement

and depressive symptoms. Health Psychology, 23, 227238.

doi:10.1037/0278-6133.23.3.227

Dew, R. E., Daniel, S. S., Goldston, D. B., McCall, W. V., Kuchibhatla,

M., Schleifer, C., Koenig, H. G. (2010). A prospective study

of religion/spirituality and depressive symptoms among adolescent psychiatric patients. Journal of Affective Disorders, 120,

149157. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2009.04.029

Ellison, C. G., & Flannelly, K. J. (2009). Religious involvement and

risk of major depression in a prospective nationwide study

of African American adults. Journal of Nervous and Mental

Disease, 197, 568573. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181b08f45

Gallup. (2013). Religion. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/

poll/1690/Religion.aspx#1

Gillman, N. (2007). How will it all end? Eschatology in science and

religion. Cross Currents, 57, 3850. Retrieved from http://www.

crosscurrents.org/GillmanSpring07.pdf

Hayward, R. D., Owen, A. D., Koenig, H. G., Steffens, D. C., &

Payne, M. E. (2012). Longitudinal relationships of religion with

posttreatment depression severity in older psychiatric patients:

Evidence of direct and indirect effects. Depression Research and

Treatment, 2012, 18. doi:10.1155/2012/745970

Health and Retirement Study (HRS 2006 Core; HRS 2008 Core)

public use dataset. (2006/2008). Produced and distributed by

the University of Michigan with funding from the National

Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740). Ann

Arbor, MI. Retrieved from http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/index.

php?p=regcou.

Hill, P. C., Pargament, K. I., Hood, R. W., Jr., McCollough, M.

E., Swyers, J. P., Larson, D. B., & Zinnbauer, B. J. (2000).

Conceptualizing religion and spirituality: Point of commonality,

points of departure. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour,

30, 5177. doi:10.1111/14685914.00119

Hurst, G. A., Williams, M. G., King, J. E., & Viken, R. (2008).

Faith-based intervention in depression, anxiety, and other mental disturbances. Southern Medical Journal, 101, 388392.

doi:10.1097/SMJ.0b013e318167a97a

Idler, E. L., & Kasl, S. V. (1992). Religion, disability, depression, and

the timing of death. American Journal of Sociology, 97, 1052

1079. doi:10.1086/229861

Iecovich, E. (2001). Religiousness and subjective well-being among

Jewish female residents of old age homes in Israel. Journal of

Religious Gerontology, 13, 3146. doi:10.1300/J078v13n01_04

King, D. A., Lyness, J. M., Duberstein, P. R., He, H., Tu, X.

M., & Seaburn, D. B. (2007). Religious involvement and

depressive symptoms in primary care elders. Psychological

Medicine, 37, 18071815. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/

S0033291707000591

Koenig, H. G. (1999). The healing power of faith. New York: Simon

& Schuster.

The Gerontologist, 2014, Vol. 00, No. 00

The Gerontologist, 2014, Vol. 00, No. 00

Stein, H. F. (2005). It aint necessarily so: The many faces of the

biopsychosocial model. Families, Systems, & Health, 23, 440

443. doi:10.1037/1091-7527.23.4.440

Sun, F., Park, N. S., Roff, L. L., Klemmack, D. L., Parker, M., Koenig,

H. G., & Allman, R. M. (2012). Predicting the trajectories of

depressive symptoms among southern community-dwelling

older adults: The role of religiosity. Aging & Mental Health, 16,

189198. doi:10.1080/13607863.2011.602959

Underwood, L. G., & Teresi, J. A. (2002). The daily spiritual experience scale: Development, theoretical description, reliability,

exploratory factor analysis, and preliminary construct validity

using health related data. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 24,

2233. doi:10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_04

Waddell, E. L., & Jacobs-Lawson, J. M. (2010). Predicting positive wellbeing in older men and women. International Journal of Aging and

Human Development, 70, 181197. doi:10.2190/AG.70.3.a

Webb, M., Charbonneau, A. M., McCann, R. A., & Gayle, K. R.

(2011). Struggling and enduring with God, religious support,

and recovery from severe mental illness. Journal of Clinical

Psychology, 67, 11611176. doi:10.1002/jclp.20838

Wink, P., & Dillon, M. (2002). Spiritual development across

the adult life course: Findings from a longitudinal study.

Journal of Adult Development, 9, 7994. doi:10.102

3/A:1013833419122

Yohannes, A. M., Koenig, H. G., Baldwin, R. C., & Connolly, M. J.

(2008). Health behaviours, depression and religiosity in older

patients admitted to intermediate care. International Journal

of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23, 735740. doi:10.1002/gps.1968

Downloaded from http://gerontologist.oxfordjournals.org/ at University Library, University of Illinois at Chicago on July 31, 2014

Rodriguez, C. A., Schonfeld, L., King-Kallimanis, B., & Amber,

M. G. (2010). Depressive symptoms and alcohol abuse/misuse in older adults: Results from the Florida BRITE project.

Best Practice in Mental Health: An International Journal, 6,

90102. Retrieved from http://essential.metapress.com/content/

r1k65231237068k1/

Satre, D., Gordon, N. P., & Weisner, C. (2007). Alcohol consumption, medical conditions and health behavior in older adults.

American Journal of Health Behavior, 31, 238248. doi:http://

dx.doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.31.3.2

Schnittker, J. (2001). When is faith enough? The effects of religious

involvement on depression. Journal for the Scientific Study of

Religion, 40, 393411. doi:10.1111/0021-8294.00065

Schotte, C. K. W., Bossche, B. V. D., Doncker, D. D., Claes, S., &

Cosyns, P. (2006). A biopsychosocial model as a guide for psychoeducation and treatment of depression. Depression and

Anxiety, 23, 321324. doi:10.1002/da.20177

Skarupski, K. A., Fitchett, G., Evans, D. A., & Mendes de Leon, C.

F. (2010). Daily spiritual experiences in a biracial, communitybased population of older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 14,

779789. doi:10.1080/13607861003713265

Smith, T. B., McCullough, M. E., & Poll, J. (2003). Religiousness

and depression: Evidence for a main effect and the moderating

influence of stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin, 129,

614636. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.4.614

Steffick, D. E. (2000). HRS/AHEAD documentation report.

Retrieved March 7, 2011, from http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/

sitedocs/userg/dr-005.pdf

Page 12 of 12

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Parade OK 3 07 June 2017Document9 pagesParade OK 3 07 June 2017Dini NanamiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5795)

- Rekap Pasien Bedah Digestive Selasa, 08 November 2016: Nama Dokter MudaDocument6 pagesRekap Pasien Bedah Digestive Selasa, 08 November 2016: Nama Dokter MudaDini NanamiPas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Soal Uts Lp3iDocument1 pageSoal Uts Lp3iDini NanamiPas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Rekap Pasien Bedah Digestive Minggu, 13 November 2016: Nama Dokter MudaDocument6 pagesRekap Pasien Bedah Digestive Minggu, 13 November 2016: Nama Dokter MudaDini NanamiPas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Art:10.1007/s00431 007 0419 XDocument8 pagesArt:10.1007/s00431 007 0419 XDini NanamiPas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- Functional Diarrhea in Toddlers (Chronic Nonspeci Fi C Diarrhea)Document4 pagesFunctional Diarrhea in Toddlers (Chronic Nonspeci Fi C Diarrhea)Dini NanamiPas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- 190 Chronic Diarrhea: EtiologyDocument14 pages190 Chronic Diarrhea: EtiologyDini NanamiPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Ruptured Cerebral Aneurysms: PerspectiveDocument4 pagesRuptured Cerebral Aneurysms: PerspectiveDini NanamiPas encore d'évaluation

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Snow ASR 1980Document16 pagesSnow ASR 1980Dini Nanami100% (1)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Crosstabs Umur Mekanisme Koping: CrosstabDocument10 pagesCrosstabs Umur Mekanisme Koping: CrosstabDini NanamiPas encore d'évaluation

- Diagnosis of Idiopathic Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus Is Supported by MRI-based Scheme: A Prospective Cohort StudyDocument11 pagesDiagnosis of Idiopathic Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus Is Supported by MRI-based Scheme: A Prospective Cohort StudyDini NanamiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- NPH BookletDocument41 pagesNPH BookletDini NanamiPas encore d'évaluation

- Limits of A Function Using Graphs and TOVDocument27 pagesLimits of A Function Using Graphs and TOVXyxa Klaire Sophia ReyesPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- JD For Digital Marketing Specialist TQH and YLAC Apr23Document2 pagesJD For Digital Marketing Specialist TQH and YLAC Apr23Naveed HasanPas encore d'évaluation

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- School Form 5 (SF 5) Report On Promotion and Progress & AchievementDocument1 pageSchool Form 5 (SF 5) Report On Promotion and Progress & AchievementMK TengcoPas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Capability Maturity Model (CMM) : 1. Initial - Work Is Performed InformallyDocument5 pagesCapability Maturity Model (CMM) : 1. Initial - Work Is Performed InformallyAyeshaaurangzeb AurangzebPas encore d'évaluation

- Mastering Apache SparkDocument1 044 pagesMastering Apache SparkArjun Singh100% (6)

- Group-8 Filipino-ScientistsDocument11 pagesGroup-8 Filipino-ScientistsAljondear RamosPas encore d'évaluation

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Professional RNDocument2 pagesProfessional RNapi-121454402Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- JS PROM PscriptDocument5 pagesJS PROM PscriptSerafinesPas encore d'évaluation

- Management Consulting - Course OutlineDocument2 pagesManagement Consulting - Course Outlineckakorot92Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sekolah Rendah Paragon: Mid Year Examination Primary 3Document2 pagesSekolah Rendah Paragon: Mid Year Examination Primary 3Mirwani Bt JubailPas encore d'évaluation

- Usability MetricsDocument4 pagesUsability MetricsAna Jiménez NúñezPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Camden Fashion: Video UK - Exercises: PreparationDocument2 pagesCamden Fashion: Video UK - Exercises: PreparationVeronika SrncováPas encore d'évaluation

- Employee Empowerment and Interpersonal Interventions: An Experiential Approach To Organization Development 8 EditionDocument69 pagesEmployee Empowerment and Interpersonal Interventions: An Experiential Approach To Organization Development 8 EditionjocaPas encore d'évaluation

- Part 2 - Earning Money Online Using AIDocument2 pagesPart 2 - Earning Money Online Using AIKaweesi BrianPas encore d'évaluation

- Guyana ICT Course and Module OverviewDocument47 pagesGuyana ICT Course and Module OverviewrezhabloPas encore d'évaluation

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Shared Reading ReflectionDocument2 pagesShared Reading Reflectionapi-242970374100% (1)

- 2 Annexure-IIDocument297 pages2 Annexure-IIStanley RoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Demo DLP Abenio MaristellaDocument15 pagesFinal Demo DLP Abenio Maristellaapi-668289592Pas encore d'évaluation

- MarkingDocument1 pageMarkingpiyushPas encore d'évaluation

- Linda AlbertDocument20 pagesLinda AlbertFungLengPas encore d'évaluation

- Jamila Bell Teaching Resume 2014 UpdatedDocument1 pageJamila Bell Teaching Resume 2014 Updatedapi-271862707Pas encore d'évaluation

- Periodical Test Diss 11 2023 2024Document4 pagesPeriodical Test Diss 11 2023 2024milaflor zalsosPas encore d'évaluation

- Effects of Child Marriage On Girls Education and EmpowermentDocument8 pagesEffects of Child Marriage On Girls Education and EmpowermentAbdulPas encore d'évaluation

- Active Listening ActivitiesDocument2 pagesActive Listening Activitiesamin.soozaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Community Development As A Process and OutputDocument34 pagesCommunity Development As A Process and OutputAngelica NavalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Aep Lesson Plan 3 ClassmateDocument7 pagesAep Lesson Plan 3 Classmateapi-453997044Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sample Questionnaire For Thesis Likert ScaleDocument4 pagesSample Questionnaire For Thesis Likert Scalednrssvyt100% (1)

- Revising The Dictionary of CanadianismsDocument16 pagesRevising The Dictionary of CanadianismsWasi Ullah KhokharPas encore d'évaluation

- (T-GCPAWS-I) Module 0 - Course Intro (ILT)Document18 pages(T-GCPAWS-I) Module 0 - Course Intro (ILT)Rafiai KhalidPas encore d'évaluation

- ASL 134 Unit 1.1 2016Document104 pagesASL 134 Unit 1.1 2016JACKSONGIRL FOR ETERNITYPas encore d'évaluation