Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Energy Irrigation Saving Energy in Irrigation

Transféré par

Sachin K GowdaCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Energy Irrigation Saving Energy in Irrigation

Transféré par

Sachin K GowdaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

FARM ENERGY INNOVATION PROGRAM - ENERGY & IRRIGATION

Saving energy in irrigation

Farmers can achieve significant energy savings through reviewing

and modifying their irrigation and other water distribution

systems. The relationship between water efficiency and energy

efficiency is a key factor when designing or modifying irrigation

solutions. Opportunities for savings include devising efficient pipe

layouts, sizing pumps correctly, introducing variable speed drives

and switching from diesel to electric pumps. Electricity is more

cost-efficient for pumping than diesel but not all farms are able

to connect to the network. Alternative electricity sources such as

solar photovoltaic may be a viable option in such cases.

Moving water

Why create an irrigation plan?

Water is heavy so moving it is energy-intensive. Approximately

65 percent of all bulk water in Australia is used by farms (ABS,

2010) and a majority of this water is pumped in some way.

Irrigation planners can help you determine the correct

layout, pump sizes and configurations, as well as when and

how long to run your irrigation systems to maximise

profitability and energy efficiency.

Irrigation farms typically move many megalitres (ML) of water,

with application rates for different crops ranging from two to

10 ML per hectare (ABS, 2013). Audits of irrigation farms have

found that energy used in irrigation can account for upwards

of 50 percent of a total farm energy bill. Additionally, all farms

pump water for stock and domestic needs. While this is likely

to be a small component of total farm energy use, there are

worthwhile savings achievable in stock and domestic pumping,

including renewable energy power sources.

Energy efficiency in irrigation has three key aspects.

Needs analysis, design and planning. It is essential

that farmers and their irrigation engineers consider

and balance water-efficiency and energy-efficiency

objectives when designing or modifying irrigation

solutions.

Optimising equipment. Ensure that pumps and

control systems optimise return on energy inputs.

Energy source. Electricity is more cost-efficient for

pumping than diesel but not all farms are able to

connect to the grid. Alternative energy sources, such

as solar, may be a viable option in such cases.

Design and planning

If you have not already done so, engage a specialist irrigation

engineer to review your irrigation system for both water and

energy efficiency.

Basic principles

The key variables affecting energy efficiency when moving

water are gravity, pressure and friction.

When designing water distribution systems and specifying

pumps, engineers consider the distance water has to be lifted

and transferred, the depth below and height above sea level,

and the friction caused within pipes and channels by layout,

diameter and operating pressures. Further complications may

arise from policy constraints on pump size, pipe diameter and

allowable pumping hours.

A further consideration is the trade-off that may apply

between water-efficiency and energy-efficiency aims. For

example, forcing water through a drip irrigation network will

use more energy that running it through channels and furrows,

but this type of system will apply water more efficiently than a

more energy-efficient centre pivot irrigation system.

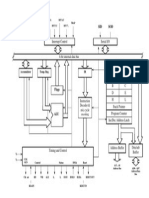

Estimated system

curve

2 pipe

Head (m)

Pump curve

Actual system

curve

3 pipe

43

Operating point

32

23

Oversized pump

Excess

head

Figure 1: A traditional windmill irrigation set-up, in which wind drives a

displacement pump and pulls water to the surface. Although this system

uses no energy (other than the wind), it is incapable of moving sufficient

amounts of water for most irrigation farms.

Flow (L/min)

Excess flow

250

400

Figure 2: Optimising a system by changing the width of piping from two

inches to three inches.

Page 1 of 4

FARM ENERGY INNOVATION PROGRAM - ENERGY & IRRIGATION

Saving energy in irrigation

Initial assessment and irrigation planning

Controls and smart systems

While many irrigation systems are superbly designed, others

may have evolved incrementally and without systematic

engineering analysis. If you suspect that your system is not

ideally configured, it may be time to consult a specialist

irrigation engineer. A more efficient layout, for example, could

enable lower specification pumps, shorter duty cycles and

major energy savings.

Sensors on irrigation systems help eliminate inefficiencies by

providing feedback on key performance parameters. Soil

moisture sensors, in conjunction with advanced controls, can

stop a system from overwatering already damp ground. Bore

sensors can alert controls on bore pumps to shut off

automatically when water levels drop below a certain point.

Timers and temperature sensors can help ensure that fields

get irrigated at optimal times and under optimal conditions.

An initial irrigation assessment is a good first step in

understanding potential savings opportunities in an existing

irrigation system set-up. A qualified irrigation planner may be

able to identify opportunities for additional irrigation

efficiencies and recommend alternative items to investigate.

If you are creating a new system, new technologies such as

sensor networks, smart metering and automation can enable

non-conventional approaches with gains in both water and

energy efficiency.

The relationship between your system and upstream water

delivery systems should also be considered, since matters such

as timing, variability and flooding may all have bearing on

system design.

Refer to supplementary paper, Irrigation sensors and

automation.

Correctly sized pumps

Oversized pumps use far more energy than is necessary, while

undersized pumps cannot always provide the volume of water

needed. To ensure that your pumps are properly sized, it is

recommended that you consult with an irrigation engineer,

who can help determine the correct total dynamic head (TDH)

for your pumps and the proper layout of your irrigation

system.

Refer to supplementary paper, Oversized pumps.

Pump maintenance

Pumps have a number of moving parts which deteriorate over

time. It is common for efficiency losses of five to 15 percent to

appear after 10 years of operation. This is due to dirt and

particle build-up increasing friction, cavitation from high water

pressures and other wear and tear. Regular maintenance not

only extends pump life but ensures optimal energy efficiency

for the age of the machine.

Refer to supplementary paper, Pump maintenance.

Energy source

Figure 3: A diesel pump outside Gunnedah, NSW, diverts water from a

nearby river up into an irrigation channel. The water then flows down the

channel and is used to flood-irrigate the surrounding fields. Excess water

from the channel is stored in an open reservoir.

Optimising equipment

Variable speed drives on pumps

Traditional pump motors have two speeds: on and off. To

achieve maximum efficiency, a higher level of precision is

useful. Variable speed drives (VSDs) provide a variety of

speeds so that pumps can run at the optimal rate for the

amount of water they are moving. The installation of VSDs on

pumps is an important energy-saving measure, as lowering the

speed of a motor by just 20 percent can produce an energy

saving of up to 50 percent.

Refer to supplementary paper, VSDs in pumps.

Pumps can be powered by diesel or electrical energy, with the

latter supplied from the grid or from renewable energy

sources. All farmers currently using diesel for pumping should

consider the feasibility of switching from diesel to electric

pumps.

Diesel versus electricity

Diesel is a versatile energy source that is ideal for use in

remote locations and can be sourced from the farms general

diesel supply. However, diesel pumps are less efficient than

electric pumps and typically require more maintenance.

Further, diesel is generally more expensive than electricity on

a dollar-per-power basis.

Feasibility of switching depends on access to the electricity

network and the cost of additional infrastructure for

connecting pumps, which can be substantial.

Electric pumps also have the advantage that they can run on

electricity generated by renewable technologies such as solar,

wind and biomass. As these technologies mature, it may

become cost-effective to supplement network power with

power generated on farm.

Refer to supplementary paper, Diesel versus electric pumps.

Page 2 of 4

FARM ENERGY INNOVATION PROGRAM - ENERGY & IRRIGATION

Saving energy in irrigation

Solar power

NSW Farmers is researching the feasibility of solar energy

solutions for pumping. The time-critical nature of irrigation

and high power requirements of irrigation systems generally

limits the potential of solar; however, hybrid solutions can be

cost-effective in some situations.

Pure solar solutions may be feasible for low-volume and nontime-critical applications for example, replenishing gravity

tanks, or for stock and domestic applications.

Refer to supplementary paper, Solar PV pumping.

Further information

Farm Energy Innovation papers

Oversized pumps

The importance of matching pump size to required pumping

volume.

Variable speed drives (VSDs) in pumps

Digital control systems can adapt pump engine speed

continuously to pumping load, saving energy.

Irrigation sensors and automation

Smart sensor networks coupled with automated control

systems can fine-tune pumping duties to plant and stock water

needs, minimising energy use and maximising water efficiency.

Pump maintenance

Maintenance is essential if youre to retain the rated operating

efficiency of both diesel and electric pumps.

Electric versus diesel pumps

Electric pumps are cheaper to power, cheaper to maintain and

easier to control. The only problem is sourcing the electricity.

Solar energy in irrigation

There is potential to use solar-generated power for all or some

of your farms pumping duties.

Figure 4: After transitioning from diesel to electric pumps, there may be an

opportunity to incorporate solar power into your pumping energy needs.

Technologies to watch

There are a number of emerging technologies relevant to

irrigation and energy in agriculture. Some of these include:

solar/diesel hybrid irrigation pumps,

gas injection in diesel pumps,

the use of recycled materials for enhanced water

storage/reduction of evaporation, and

sensor technology and digital control systems.

The effectiveness and affordability of such technologies is

improving steadily. While the investment numbers might not

yet make these attractive financial options, we encourage all

farmers to keep a watching brief on these areas.

Other sources

Irrigation Australia

The website of this national body covering urban and rural

irrigation throughout Australia includes figures and resources

for irrigators.

irrigation.org.au

NSW Irrigators Council

The NSW Irrigators Council is a peak body that represents

irrigators throughout NSW, with a focus on water-use

management and irrigation policy for NSW stakeholders.

www.nswic.org.au

Energy-saving tips for irrigators

A terrific in-depth report addressing various efficiency

measures and tools for irrigators.

attra.ncat.org/attra-pub/summaries/summary.php?pub=119

Page 3 of 4

FARM ENERGY INNOVATION PROGRAM - ENERGY & IRRIGATION

Saving energy in irrigation

References

ABS, 2010. Irrigation on Australian farms. [Online]

Available at:

www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/7d12b0f6763c78caca257

061001cc588/a1372142a0cca480ca2573d200111005!OpenDo

cument

[Accessed February 2014].

ABS, 2013. Water Use on Australian Farms 2011-12. [Online]

Available at:

www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4618.0main+feat

ures62011-12

[Accessed January 2014].

National program for sustainable irrigation, 2008. Irrigation in

Australia: Facts and figures. [Online]

Available at:

lwa.gov.au/files/products/national-program-sustainableirrigation/pn22088/pn22088.pdf

[Accessed February 2014].

NSW Government Energy Savings Scheme, 2014. List of

accredited certificate providers. [Online]

Available at:

www.ess.nsw.gov.au/Overview_of_the_scheme/List_of_Accre

dited_Certificate_Providers

[Accessed January 2014].

NSW Farm Energy Innovation Program NSW Farmers Association 2013

NSW Farmers gives no warranty regarding this publications accuracy, completeness, currency or suitability for any particular purpose and to the extent

permitted by law, does not accept any liability for loss or damages incurred as a result of reliance placed upon the content of this publication. This publication

is provided on the basis that all persons accessing it undertake responsibility for assessing the relevance and accuracy of its content. The mention of any

specific product in this paper is for example only and is not intended as an endorsement. This activity received funding from the Department of Industry as

part of the Energy Efficiency Information Grants Program. The views expressed herein are not necessarily the views of the Commonwealth of Australia, and

the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for any information or advice contained herein.

Head Office: 02 9478 1000

Energy Info Line: 02 9478 1013

www.nswfarmers.org.au

http://ee.ret.gov.au

Content produced with

assistance from Energetics

www.energetics.com.au

Page 4 of 4

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Theory of Elasticity and Plasticity. (CVL 622) M.Tech. CE Term-2 (2017-18)Document2 pagesTheory of Elasticity and Plasticity. (CVL 622) M.Tech. CE Term-2 (2017-18)er.praveenraj30Pas encore d'évaluation

- Kemira, Leonard Dan Bethel Acid FormicDocument22 pagesKemira, Leonard Dan Bethel Acid FormicBen Yudha SatriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Aee1 SkriptDocument186 pagesAee1 SkriptCristian PanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Criteri-7 SSR-2020-21 - 18042022 - 04-27Document19 pagesCriteri-7 SSR-2020-21 - 18042022 - 04-27Sachin K GowdaPas encore d'évaluation

- Newsletter Even 2021-22Document9 pagesNewsletter Even 2021-22Sachin K GowdaPas encore d'évaluation

- Tranducers NotesDocument3 pagesTranducers NotesSachin K GowdaPas encore d'évaluation

- New Project List 1Document12 pagesNew Project List 1Sachin K GowdaPas encore d'évaluation

- Monitoring of Honey Bee Hiving System Using SensorDocument4 pagesMonitoring of Honey Bee Hiving System Using SensorSachin K GowdaPas encore d'évaluation

- CIRCUITRIXDocument1 pageCIRCUITRIXSachin K GowdaPas encore d'évaluation

- Privacy and Security in GSMDocument6 pagesPrivacy and Security in GSMSachin K GowdaPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 7 TransducerDocument20 pagesUnit 7 TransducerSachin K GowdaPas encore d'évaluation

- Measuring Instruments (Autosaved)Document23 pagesMeasuring Instruments (Autosaved)Sachin K GowdaPas encore d'évaluation

- Government Holidays 2017Document10 pagesGovernment Holidays 2017Sachin K GowdaPas encore d'évaluation

- Measuring Instruments: Ms. Shreedevi S Assistant Professor Department of ECEDocument20 pagesMeasuring Instruments: Ms. Shreedevi S Assistant Professor Department of ECESachin K GowdaPas encore d'évaluation

- ECE 3rd Syllabus PDFDocument18 pagesECE 3rd Syllabus PDFacpscribdPas encore d'évaluation

- 1.7 Frequency HoppingDocument2 pages1.7 Frequency HoppingMaria Anto Jony SelvanPas encore d'évaluation

- GSM Logical ChannelsDocument25 pagesGSM Logical ChannelsSachin K GowdaPas encore d'évaluation

- Interrupt Control Serial I/O: SID SODDocument1 pageInterrupt Control Serial I/O: SID SODpra_zara2637Pas encore d'évaluation

- V Tu RV Ce 2017 HolidaysDocument2 pagesV Tu RV Ce 2017 HolidaysSachin K GowdaPas encore d'évaluation

- Microprocessor 8086Document72 pagesMicroprocessor 8086Sachin K GowdaPas encore d'évaluation

- MP Notes 3 InterfacingDocument7 pagesMP Notes 3 InterfacingSachin K GowdaPas encore d'évaluation

- Applications of Laplace TransformDocument13 pagesApplications of Laplace Transformsnehashweta27Pas encore d'évaluation

- DC GeneratorDocument7 pagesDC GeneratorSachin K GowdaPas encore d'évaluation

- Corporation Water Supply Management Syste1Document2 pagesCorporation Water Supply Management Syste1Sachin K GowdaPas encore d'évaluation

- Networks: Basic Concepts: CentralityDocument27 pagesNetworks: Basic Concepts: CentralitySachin K GowdaPas encore d'évaluation

- MP NotesDocument16 pagesMP NotesSachin K GowdaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sai Vidya Institute of TechnologyDocument5 pagesSai Vidya Institute of TechnologySachin K GowdaPas encore d'évaluation

- Two PortDocument58 pagesTwo PortKamal Shivaji NettipalliPas encore d'évaluation

- Network AnalysisDocument16 pagesNetwork AnalysisSheilalokesh SheilaPas encore d'évaluation

- Basic Electronic & Transistor Circuits PDFDocument54 pagesBasic Electronic & Transistor Circuits PDFSandeep GoyalPas encore d'évaluation

- Target Audience, Hosting and Business IssuesDocument31 pagesTarget Audience, Hosting and Business IssuesSachin K GowdaPas encore d'évaluation

- Network Analysis December 2011Document2 pagesNetwork Analysis December 2011Sachin K GowdaPas encore d'évaluation

- Dow Elite 5401G TDSDocument3 pagesDow Elite 5401G TDSAli RazuPas encore d'évaluation

- Catalogo Cadenas de Ingenieria PDFDocument136 pagesCatalogo Cadenas de Ingenieria PDFGlicerio Bravo GaticaPas encore d'évaluation

- TRUMPF Technical Data Sheet TruDiskDocument9 pagesTRUMPF Technical Data Sheet TruDiskHLPas encore d'évaluation

- 05 PDFDocument1 page05 PDFdruwid6Pas encore d'évaluation

- Regular Solution TheoryDocument4 pagesRegular Solution TheoryLouie G NavaltaPas encore d'évaluation

- D 6988 - 03 Medicion de CalibreDocument7 pagesD 6988 - 03 Medicion de CalibreMiguelAngelPerezEsparzaPas encore d'évaluation

- (M1 Technical) Cpe0011lDocument12 pages(M1 Technical) Cpe0011lJoel CatapangPas encore d'évaluation

- The Key To Super Consciousness Chapter 1Document6 pagesThe Key To Super Consciousness Chapter 1Will FortunePas encore d'évaluation

- FuelDocument172 pagesFuelImtiaz KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Banner Engineering - Glass Fiber Series - CatalogDocument43 pagesBanner Engineering - Glass Fiber Series - CatalogTavo CoxPas encore d'évaluation

- Nano RamDocument7 pagesNano Ramसाहिल विजPas encore d'évaluation

- Thermal Stress MonitoringDocument78 pagesThermal Stress MonitoringSIVA KAVYAPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment N1Document9 pagesAssignment N1Rania ChPas encore d'évaluation

- 17 Capacitors and Inductors in AC CircuitsDocument12 pages17 Capacitors and Inductors in AC CircuitsAbhijit PattnaikPas encore d'évaluation

- Preparation of Silver Nanoparticles in Cellulose Acetate Polymer and The Reaction Chemistry of Silver Complexes in The PolymerDocument4 pagesPreparation of Silver Nanoparticles in Cellulose Acetate Polymer and The Reaction Chemistry of Silver Complexes in The Polymer1Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Facile Synthesis, Characterization of N-Substituted 7-Methoxy 3-Phenyl 4 (3-Piperzin - 1-Yl-Propoxy) Chromen-2-OneDocument21 pagesA Facile Synthesis, Characterization of N-Substituted 7-Methoxy 3-Phenyl 4 (3-Piperzin - 1-Yl-Propoxy) Chromen-2-OneNalla Umapathi ReddyPas encore d'évaluation

- Physics ExerciseDocument6 pagesPhysics ExerciseLaw Jing SeePas encore d'évaluation

- Transformasi Dalam MatematikDocument39 pagesTransformasi Dalam MatematikMas Izwatu Solehah MiswanPas encore d'évaluation

- Multi Meter Triplett 630-NA Tested by ZS1JHGDocument2 pagesMulti Meter Triplett 630-NA Tested by ZS1JHGJohn Howard GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparison of Heald Frame Motion Generated by Rotary Dobby and Crank & Cam Shedding MotionsDocument6 pagesComparison of Heald Frame Motion Generated by Rotary Dobby and Crank & Cam Shedding MotionsKannan KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Data SheetDocument5 pagesData SheetMubashir HasanPas encore d'évaluation

- PT Flash Handout 2010Document24 pagesPT Flash Handout 2010Zahraa DakihlPas encore d'évaluation

- Effect of Sawdust Filler With Kevlarbasalt Fiber On The MechanicalDocument6 pagesEffect of Sawdust Filler With Kevlarbasalt Fiber On The MechanicalKarim WagdyPas encore d'évaluation

- A Mini Project ReportDocument37 pagesA Mini Project ReportChintuu Sai100% (2)

- JEE Advanced 2019 Paper AnalysisDocument25 pagesJEE Advanced 2019 Paper AnalysisPankaj BaidPas encore d'évaluation

- Operating Instructions: Vegapuls 67Document84 pagesOperating Instructions: Vegapuls 67SideparPas encore d'évaluation

- Indian Engineering Services (IES) : Reference BooksDocument6 pagesIndian Engineering Services (IES) : Reference BooksKapilPas encore d'évaluation