Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Embossing Tech

Transféré par

mohsintCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Embossing Tech

Transféré par

mohsintDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Embossing Basics

Definition of embossing: In the broadest sense, it means to change a surface from flat to

shaped, so that some areas are raised relative to other areas. On this website, I use the

word "embossing" only as it applies to thin and malleable materials. In most cases, each

raised area on one surface of the thin material is matched by a recessed area on the

opposite side, and vice versa. One exception to this is sometimes called "pattern

pressing". This occurs when areas of one surface are recessed while the corresponding

areas of opposite side remain flat or are also recessed, causing the material to become

thinner in those areas. This is typical when embossing leather or when using heated

embossing on a nonwoven to create thermal bonding. High pressure pinpoint pressing with

very narrow wheels against a hard smooth cylinder is used to create ply bonding (for facial

tissue and bath tissue), and this is sometimes called edge embossing.

Materials that are embossed: Just about anything that is thin, flat, and malleable can be

embossed. This includes paper, plastic film, metal foil, nonwovens, textile fabric, leather, and

even glass. These materials may be provided in continuous form (like paper unwinding from

a roll), or in discrete form (cut into individual sheets before embossing).

Purpose of embossing: Sometimes embossing is done for purely decorative

reasons. However, in most cases, the purpose of embossing is to change the physical

characteristics of the material. Embossing a metal foil with a fine texture pattern makes it

much easier to handle the foil within the machine that wraps it around a piece of chewing

gum. Embossing a plastic film changes its elastic properties dramatically. Embossing tissue

paper improves absorbency and flexibility, but almost always at the expense of

strength. Embossing increases the overall thickness of the material. In some cases,

embossing is used to bond two or more layers of material.

Methods of embossing are often determined by the properties of the material, and how it is

provided. The material may be malleable or fluid, or somewhere between. It may be

provided in continuous form (without breaks), or in discrete lengths or pieces.

For malleable materials, a permanent shape change is imposed simply by the

application of force. This usually has a very significant effect upon the mechanical

properties of the material. Most tissue paper is embossed this way, while the paper is

completely dry.

For fluid materials, the embossing step starts out more like casting onto a mold while

the material is still fluid, and then the material is changed from fluid to solid. This

reduces the effect of the embossing upon the strength and elasticity of the material. In

the case of tissue paper, the fluid state is the suspension of paper fibers in water, the

mold is the forming wire, and the material becomes more solid as the water is

removed.

Some embossed materials are somewhere between malleable and fluid. For

instance, tissue paper can be shaped after it is formed, but still very wet. The results

are much different from traditional "dry embossing".

When the material to be embossed has been cut into discrete lengths, it is usually

necessary to employ an intermittent method like stamp embossing, where the sheet is

pressed between two plates.

When the material to be embossed is provided in continuous form, without breaks,

then the preferred method is rotary embossing, where the material is passed

between embossing rollers. Rotary embossing is much, much faster than any of the

intermittent embossing methods.

Embossing, in Greater Detail

The remainder of this discussion will cover only continuous rotary embossing, and will focus

upon how this is applied to absorbent tissue paper in the dry state. Much of this is also

relevant to embossing other materials.

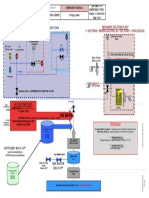

The fundamental mechanism in rotary embossing is the embossing nip, which is the area

where two embossing rollers come into contact. The simplest embossing applications use

only a single nip. Others may involve several embossing nips, either in series or in

parallel. Sometimes embossing is directly combined with other finishing processes, such as

printing or laminating (which involve other nips).

The types of embossing nips are named after the materials that have traditionally been used

for the surfaces of the embossing rollers. These materials are still the most common, but

newer materials are being developed.

S/S (steel-to-steel): Both rollers are engraved with patterns that are designed to

engage each other in some way. The surfaces of these rollers must be hard enough

and durable enough so that the raised protuberances on each is able to deform the

paper. Traditionally, both surfaces have been steel, and therefore this type of

embossing nip is called a "Steel-to-Steel" or S/S embossing nip.

R/S (rubber-to-steel): Only one of the rollers is engraved, while the other roller is

covered with a elastic material like rubber. The surface of the elastic material is

smooth, except while it is being pressed against the engraved roller in the embossing

nip. Elastic recovery to its original smooth shape is extremely rapid. The surface of

the engraved roller must be hard enough and durable enough to deform not only the

paper that is being embossed, but also must deform the elastic material of the

opposing roller (which requires much more force and energy than the paper

does). Traditionally, the engraved surface has been steel and the deformable surface

has been rubber. However, the engraved roller could have a laser engraved surface

made of very hard rubber, while the smooth roller could have a surface made of an

elastomeric plastic.

P/S (paper-to-steel): There is another type of embossing nip which is really a hybrid

between the two described above. It is mostly used only for paper napkins where the

embossing must produce bonding of multiple plies and/or high visual definition in the

pattern. In this case, the steel roller is engraved with the embossing pattern, while the

opposing roller is a paper-filled roll that is initially smooth. A "run-in" period is required

to transfer the pattern from the engraved steel surface into the paper surface initially,

and also to repair any damage that may later occur to the paper surface.

Embossing nips may be combined in parallel or in series.

Serial nips: This is sometimes used to superimpose one embossing pattern over

another, by passing the paper first through one embossing nip, and then through

another. It works best when the first pattern is a very fine-scale pattern that has

complete coverage over the paper (like a micro embossing pattern), and the second

pattern is composed of larger figures with large open areas between them (like a spot

embossing pattern). However, a very similar effect can often be achieved in a single

nip less expensively.

Parallel nips: This is only used for products that have two or more plies. In a twoply product, one ply is passed through one nip while the other ply is passed through

the other nip, and then the two plies are brought back together again, usually with

some method of bonding the plies together. This is most often employed in two-ply

laminated towel products, which use very carefully placed dots of glue to bond the

plies together. The choice of embossing patterns, how the pattern on each ply aligns

with the pattern on the other ply, and the placement of the glue are all critical elements

in the design of an embossed/laminated paper towel product.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Lapping Is A: Machining AbrasiveDocument4 pagesLapping Is A: Machining AbrasiveRajesh AthishPas encore d'évaluation

- Guidance Test SpecimensDocument10 pagesGuidance Test SpecimensferrarifanaticPas encore d'évaluation

- New Blank DocumentDocument10 pagesNew Blank DocumentMahmoudPas encore d'évaluation

- Adding and Altering: Surface FinishingDocument11 pagesAdding and Altering: Surface FinishingVijay Raj PuniaPas encore d'évaluation

- EmbossingDocument7 pagesEmbossingRavi Singh100% (1)

- Understanding Paper GrainDocument3 pagesUnderstanding Paper GrainNishant AsheshPas encore d'évaluation

- NotesDocument5 pagesNotesVarun SrivastavaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Application of Modified Starches at The Size PressDocument18 pagesThe Application of Modified Starches at The Size PressPeter de Clerck100% (1)

- Ductile MaterialsDocument2 pagesDuctile MaterialssaruPas encore d'évaluation

- Movement of The Book Spine, Tom ConroyDocument79 pagesMovement of The Book Spine, Tom ConroyKevin ShebyPas encore d'évaluation

- Classification and Forming Methods of Sheet Metal PartsDocument39 pagesClassification and Forming Methods of Sheet Metal PartssasikumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Calendering ProcessDocument14 pagesCalendering ProcessRony ShielaPas encore d'évaluation

- Injection Molding DesignDocument17 pagesInjection Molding DesignprasathbalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Screw DesignDocument13 pagesScrew DesignDiptendu Basu100% (2)

- Superplastic Forming and Diffusion BondingDocument4 pagesSuperplastic Forming and Diffusion BondingSanjeev ShuklaPas encore d'évaluation

- Thermoforming: Vacuum Forming - A Vacuum Is Formed Between The Mold Cavity and TheDocument7 pagesThermoforming: Vacuum Forming - A Vacuum Is Formed Between The Mold Cavity and TheVikas Mani TripathiPas encore d'évaluation

- LO.9-Elfayoum Chemi Club: Made By: Mahmoud TahaDocument31 pagesLO.9-Elfayoum Chemi Club: Made By: Mahmoud Tahabebo atefPas encore d'évaluation

- Cause of WarpageDocument7 pagesCause of WarpageAnonymous 8lxxbNcA0sPas encore d'évaluation

- Roller Coating Application TechniquesDocument4 pagesRoller Coating Application TechniquesAnujPas encore d'évaluation

- CE-213 Lecture 1 Fundamental of Stress & StrainDocument17 pagesCE-213 Lecture 1 Fundamental of Stress & StrainNazia ZamanPas encore d'évaluation

- Introdusction To Flexographic PrintDocument77 pagesIntrodusction To Flexographic PrintTamas RaduPas encore d'évaluation

- Ceramic ProcessingDocument37 pagesCeramic Processingmiroali4023Pas encore d'évaluation

- 9 - FinishingDocument4 pages9 - FinishingAdrian ColaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Pultrusion - : High Productivity Now, Getting Even BetterDocument12 pagesPultrusion - : High Productivity Now, Getting Even BetterBruno PaulinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Relationship Between Roller Compression, Contact Area, and Clamp ForceDocument6 pagesRelationship Between Roller Compression, Contact Area, and Clamp ForceavgpaulPas encore d'évaluation

- Study Material 7 - DrawingDocument7 pagesStudy Material 7 - DrawingAvik DasPas encore d'évaluation

- Warpage of Fibre Reinforced PlasticsDocument8 pagesWarpage of Fibre Reinforced PlasticsSantolashPas encore d'évaluation

- PT - 241properties and Characteristics of ParticlesDocument49 pagesPT - 241properties and Characteristics of ParticlesAli HasSsan100% (1)

- 011014048Document4 pages011014048Adrian Cocis100% (1)

- Thermoforming Design Guidelines-020810Document46 pagesThermoforming Design Guidelines-020810AmolPagdal100% (1)

- Bending (Metalworking)Document7 pagesBending (Metalworking)Odebiyi StephenPas encore d'évaluation

- Bending (Metalworking)Document7 pagesBending (Metalworking)semizxxxPas encore d'évaluation

- Extrusion InformationDocument29 pagesExtrusion InformationNishant1993100% (1)

- Twin Screw Extrusion SystemDocument3 pagesTwin Screw Extrusion SystemShivanshu SoniPas encore d'évaluation

- Vacuum FormingDocument26 pagesVacuum FormingRavi PratapPas encore d'évaluation

- Injection Molding Design GuidelinesDocument13 pagesInjection Molding Design GuidelinesSreedhar PugalendhiPas encore d'évaluation

- Issues To Address... : - What Is Wear? - Types of Wear? - Wear Control - Factors Affecting WearDocument40 pagesIssues To Address... : - What Is Wear? - Types of Wear? - Wear Control - Factors Affecting WearIsmail IbrahimPas encore d'évaluation

- One Material Property That Is Widely Used and Recognized Is The Strength of A MaterialDocument3 pagesOne Material Property That Is Widely Used and Recognized Is The Strength of A MaterialWaleed JaddiPas encore d'évaluation

- Calendering FinishDocument32 pagesCalendering Finishmdtawhiddewan1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Leveling Sheet Metal to Remove Internal StressesDocument4 pagesLeveling Sheet Metal to Remove Internal StressesangelokyoPas encore d'évaluation

- Compression and Compaction: A Seminar OnDocument63 pagesCompression and Compaction: A Seminar OnsrikanthgaliPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 3Document4 pagesModule 3Zeref DragneelPas encore d'évaluation

- S Announcement 16847Document9 pagesS Announcement 16847C2H5OHPas encore d'évaluation

- Book BindingDocument14 pagesBook Bindingpesticu100% (2)

- Single Screw ExtrusionDocument5 pagesSingle Screw ExtrusionAli RazuPas encore d'évaluation

- Press Tool Cutting ForceDocument1 pagePress Tool Cutting Forceanmol6237Pas encore d'évaluation

- Characterization of Single ParticleDocument29 pagesCharacterization of Single ParticlePiyush RajPas encore d'évaluation

- 1.11 Types of 3D PrintingDocument2 pages1.11 Types of 3D Printingsavone93Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sheet Metal Cutting (Shearing)Document7 pagesSheet Metal Cutting (Shearing)Sachin PatelPas encore d'évaluation

- Design For Plastics Unit 7Document10 pagesDesign For Plastics Unit 7Harinath GowdPas encore d'évaluation

- Printmaking NotesDocument13 pagesPrintmaking Notespaola_rdzcPas encore d'évaluation

- 3 Metal StampingDocument2 pages3 Metal StampingRavi Sharma M PPas encore d'évaluation

- Functional FinishingDocument31 pagesFunctional Finishingsujal jhaPas encore d'évaluation

- Physics ProjectDocument26 pagesPhysics ProjectCH Tarakeesh75% (8)

- Plastics ExtrusionDocument37 pagesPlastics Extrusionshashanksir80% (5)

- Focus On RheologyDocument8 pagesFocus On RheologyVinay BhayaPas encore d'évaluation

- Metal Forming Analysis Lab ManualDocument9 pagesMetal Forming Analysis Lab Manuallecturer.parul100% (1)

- Duct Tape Engineer: The Book of Big, Bigger, and Epic Duct Tape ProjectsD'EverandDuct Tape Engineer: The Book of Big, Bigger, and Epic Duct Tape ProjectsÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Ultrasonic Fabric Embossing Machine PDFDocument7 pagesUltrasonic Fabric Embossing Machine PDFmohsintPas encore d'évaluation

- Samples in Apparel IndustryDocument3 pagesSamples in Apparel IndustrymohsintPas encore d'évaluation

- Merchandising ActivitiesDocument1 pageMerchandising ActivitiesmohsintPas encore d'évaluation

- Merchandising ActivitiesDocument1 pageMerchandising ActivitiesmohsintPas encore d'évaluation

- Anatomy of an AI SystemDocument23 pagesAnatomy of an AI SystemDiego Lawliet GedgePas encore d'évaluation

- TEC Services, Inc.: Thermal Aerosol Generator, Model Compact (Inert Gas)Document1 pageTEC Services, Inc.: Thermal Aerosol Generator, Model Compact (Inert Gas)S DasPas encore d'évaluation

- Bailey - Butch - Queens - Up - in - Pumps - Gender, - Performance, - and - ... - (Chapter - One. - Introduction - Peforming - Gender, - Creating - Kinship, - Forging - ... )Document28 pagesBailey - Butch - Queens - Up - in - Pumps - Gender, - Performance, - and - ... - (Chapter - One. - Introduction - Peforming - Gender, - Creating - Kinship, - Forging - ... )ben100% (1)

- Nuclear Power Corporation of India LimitedDocument11 pagesNuclear Power Corporation of India Limitedkevin desaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Bilge Oily Water SeparatorDocument25 pagesBilge Oily Water Separatornguyenvanhai19031981100% (2)

- Importance of Bus Rapid Transit Systems (BRTSDocument7 pagesImportance of Bus Rapid Transit Systems (BRTSAnshuman SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- School Form 1 SF 1 10Document6 pagesSchool Form 1 SF 1 10ALEX SARAOSOSPas encore d'évaluation

- Emergency procedures for shipboard fire suppression systemsDocument1 pageEmergency procedures for shipboard fire suppression systemsImmorthalPas encore d'évaluation

- 1.4 Case Study - The Cost of Poor Communication - Technical Writing EssentialsDocument8 pages1.4 Case Study - The Cost of Poor Communication - Technical Writing EssentialssnehaashujiPas encore d'évaluation

- Facebook Ads Defeat Florida Ballot InitiativeDocument3 pagesFacebook Ads Defeat Florida Ballot InitiativeGuillermo DelToro JimenezPas encore d'évaluation

- REPLACEMENT IDLER TIRE SPECIFICATIONSDocument2 pagesREPLACEMENT IDLER TIRE SPECIFICATIONSLuis HumPas encore d'évaluation

- Tipe Tubuh (Somatotype) Dengan Sindrom Metabolik Pada Wanita Dewasa Non-Obesitas Usia 25-40 TahunDocument9 pagesTipe Tubuh (Somatotype) Dengan Sindrom Metabolik Pada Wanita Dewasa Non-Obesitas Usia 25-40 TahunJessica Ester ExaudiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment: New Product Development PROJECT TITLE: Safety Alarm For Construction WorkerDocument21 pagesAssignment: New Product Development PROJECT TITLE: Safety Alarm For Construction WorkerHazim ZakiPas encore d'évaluation

- q2 w6 Asteroids Comets MeteorsDocument61 pagesq2 w6 Asteroids Comets MeteorsxenarealePas encore d'évaluation

- NotesAcademy - Year 3&4 ChemistryDocument119 pagesNotesAcademy - Year 3&4 Chemistrydarkadain100% (1)

- HIlbro SurgicalDocument70 pagesHIlbro Surgicalshazay_7733% (3)

- Suriaga, Angelica F. - Module 23 - Classroom ClimateDocument21 pagesSuriaga, Angelica F. - Module 23 - Classroom Climateangelica suriagaPas encore d'évaluation

- LSE100 Past Year Questions (2014/5)Document2 pagesLSE100 Past Year Questions (2014/5)Jingwen ZhangPas encore d'évaluation

- 008 Cat 6060 Attachment Functions BHDocument15 pages008 Cat 6060 Attachment Functions BHenrico100% (3)

- Caldikind Suspension Buy Bottle of 200 ML Oral Suspension at Best Price in India 1mgDocument1 pageCaldikind Suspension Buy Bottle of 200 ML Oral Suspension at Best Price in India 1mgTeenaa DubashPas encore d'évaluation

- AppoloDocument2 pagesAppoloRishabh Madhu SharanPas encore d'évaluation

- 3.factors and Techniques Influencing Peri-Implant Papillae - PDFDocument12 pages3.factors and Techniques Influencing Peri-Implant Papillae - PDFMargarita María Blanco LópezPas encore d'évaluation

- Mrs Jenny obstetric historyDocument3 pagesMrs Jenny obstetric historyDwi AnggoroPas encore d'évaluation

- Chaity-Group New ProfileDocument39 pagesChaity-Group New ProfileShajedul PalashPas encore d'évaluation

- Tips For A Successful Approval of A Fire Alarm SystemDocument9 pagesTips For A Successful Approval of A Fire Alarm SystemradusettPas encore d'évaluation

- Setting TrolleyDocument19 pagesSetting TrolleyLennard SegundoPas encore d'évaluation

- 8086 Instruction Set and Assembly Language ProgramDocument13 pages8086 Instruction Set and Assembly Language Programwaheed azizPas encore d'évaluation

- Fault Code: 352 Sensor Supply 1 Circuit - Voltage Below Normal or Shorted To Low SourceDocument3 pagesFault Code: 352 Sensor Supply 1 Circuit - Voltage Below Normal or Shorted To Low SourceFernando AguilarPas encore d'évaluation

- Machine Learning NNDocument16 pagesMachine Learning NNMegha100% (1)

- Commercial Checklist-Print - 2008 Nec - 08-28-08Document23 pagesCommercial Checklist-Print - 2008 Nec - 08-28-08akiferindrariskyPas encore d'évaluation