Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Art 3A10.1186 2Fs12884 016 0815 1

Transféré par

Anonymous glr9JT7Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Art 3A10.1186 2Fs12884 016 0815 1

Transféré par

Anonymous glr9JT7Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Grooten et al.

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2016) 16:22

DOI 10.1186/s12884-016-0815-1

STUDY PROTOCOL

Open Access

Early nasogastric tube feeding in optimising

treatment for hyperemesis gravidarum: the

MOTHER randomised controlled trial

(Maternal and Offspring outcomes after

Treatment of HyperEmesis by Refeeding)

Iris J. Grooten1,2*, Ben W. Mol3, Joris A. M. van der Post1, Carrie Ris-Stalpers1,4, Marjolein Kok1, Joke M. J. Bais5,

Caroline J. Bax6, Johannes J. Duvekot7, Henk A. Bremer8, Martina M. Porath9, Wieteke M. Heidema10,

Kitty W. M. Bloemenkamp11, Hubertina C. J. Scheepers12, Maureen T. M. Franssen13, Martijn A. Oudijk1,

Tessa J. Roseboom1,2 and Rebecca C. Painter1

Abstract

Background: Hyperemesis gravidarum (HG), or intractable vomiting during pregnancy, is the single most

frequent cause of hospital admission in early pregnancy. HG has a major impact on maternal quality of life

and has repeatedly been associated with poor pregnancy outcome such as low birth weight. Currently,

women with HG are admitted to hospital for intravenous fluid replacement, without receiving specific

nutritional attention. Nasogastric tube feeding is sometimes used as last resort treatment. At present no

randomised trials on dietary or rehydration interventions have been performed. Small observational studies

indicate that enteral tube feeding may have the ability to effectively treat dehydration and malnutrition and

alleviate nausea and vomiting symptoms. We aim to evaluate the effectiveness of early enteral tube feeding

in addition to standard care on nausea and vomiting symptoms and pregnancy outcomes in HG patients.

Methods/Design: The MOTHER trial is a multicentre open label randomised controlled trial (www.studies-obsgyn.nl/

mother). Women 18 years hospitalised for HG between 5 + 0 and 19 + 6 weeks gestation are eligible for participation.

After informed consent participants are randomly allocated to standard care with intravenous rehydration or early

enteral tube feeding in addition to standard care. All women keep a weekly diary to record symptoms and dietary

intake until 20 weeks gestation. The primary outcome will be neonatal birth weight. Secondary outcomes will be the

24-h Pregnancy Unique Quantification of Emesis and nausea score (PUQE-24), maternal weight gain, dietary intake,

duration of hospital stay, number of readmissions, quality of life and side-effects. Also gestational age at birth, placental

weight, umbilical cord plasma lipid concentration and neonatal morbidity will be evaluated. Analysis will be according

to the intention to treat principle.

(Continued on next page)

* Correspondence: i.j.grooten@amc.uva.nl

1

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Academic Medical Centre,

University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2

Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Bioinformatics,

Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The

Netherlands

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

2016 Grooten et al. Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to

the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver

(http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Grooten et al. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2016) 16:22

Page 2 of 6

(Continued from previous page)

Discussion: With this trial we aim to clarify whether early enteral tube feeding is more effective in treating HG than

intravenous rehydration alone and improves pregnancy outcome.

Trial registration: Trial registration number: NTR4197. Date of registration: October 2nd 2013.

Keywords: Hyperemesis, Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy, Tube feeding, Intravenous rehydration, Effectiveness, Outcomes

Background

Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (NVP) is common, affecting 5080 % of pregnancies [1]. Often these symptoms

are mild and self-limiting and resolve without intervention

in the second trimester. In other cases however, severe intractable vomiting can lead to dehydration, electrolyte disturbances and significant weight loss necessitating

hospital admission. The condition of intractable vomiting

during pregnancy is called hyperemesis gravidarum

(HG) [2]. HG has repeatedly been associated with

poor pregnancy outcome including low birth weight

(LBW, <2500 g: OR 1.42), small for gestational age

(OR 1.28) and prematurity (OR 1.32) [24]. Furthermore,

HG has a major impact on maternal wellbeing and quality

of life [57] and remains the largest single cause of hospital admission in early pregnancy [8, 9]. However, the

aetiology of HG is poorly understood [1012].

Approximately 0.82 % of all pregnancies are complicated by HG [2]. Currently, there are no treatments with

proven efficacy available according to the latest Cochrane

review on interventions for nausea and vomiting in early

pregnancy [1]. Hospitalisation can be required for intravenous treatment of dehydration and electrolyte imbalance.

Currently, women who suffer from HG do not receive any

particular nutritional attention, although enteral tube feeding is sometimes used as a treatment of last resort [2, 13].

Enteral tube feeding effectively treats both dehydration and

malnutrition in non-pregnant patients with poor intake

[14] and has been shown to be safer than parenteral nutrition in pregnancy [15]. Moreover, in several small

studies in women with HG, which did not employ a

control group, it alleviated symptoms and was well

tolerated if continued in a home setting [1618].

There have been no controlled trials to investigate

the extent to which enteral tube feeding can positively

affect pregnancy outcome and maternal quality of life,

nausea and vomiting symptoms or time in hospital.

At present, there is no evidence on the effectiveness

and efficiency of rehydration and dietary interventions

for HG. We hypothesise that enteral tube feeding in

addition to standard care is a more effective treatment

for HG symptoms than standard care with intravenous

rehydration alone, and improves pregnancy outcome.

This multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT) aims

to compare early enteral tube feeding in addition to

standard care, with standard care alone. Outcomes of interest are birth weight and maternal nausea and vomiting

symptoms, maternal quality of life, duration of hospitalisation, weight gain and neonatal morbidity. The study is

conducted within the Dutch Consortium for Studies in Obstetrics, Fertility and Gynaecology (www.studies-obsgyn.nl).

Methods/Design

Participants/ eligibility criteria

Patients 18 years of age are eligible if they have been

admitted to hospital because of HG (first admission or

readmission) at a gestational age between 5 + 0 and 19 +

6 weeks. Patients with singleton or multiple pregnancies

are eligible. A diagnosis of HG is made if excessive

nausea or vomiting necessitates hospital admission, in

the absence of any other obvious cause such as drug

induced vomiting or infection.

Exclusion criteria are mola hydatidosa pregnancy,

non-vital pregnancy, acute infection causing vomiting

(e.g. appendicitis, pyelonephritis), contraindication for

enteral tube feeding (e.g. oesophageal varices, allergies

to enteral tube mix compounds) or HIV infection.

Procedures, recruitment and randomisation

This study is a nationwide multicentre open label RCT

conducted within the Dutch Consortium for Studies in

Obstetrics, Fertility and Gynaecology, a nationwide collaboration of hospitals in the Netherlands. The staff and/

or local research coordinator of the participating hospitals identifies eligible women. After counselling and

reading the patient information form, patients are asked

for written informed consent. Patient information is provided in Dutch and English. See Fig. 1.

Randomisation is performed by a web based computerised program using permuted-block randomisation.

Randomisation is allocated in a 1:1 ratio for standard

care or enteral tube feeding in addition to standard care,

with a block size of four. Stratification according to

centre is applied.

Intervention

Participants are allocated to standard care or enteral tube

feeding in addition to standard care. Standard care consists of intravenous rehydration and, when considered necessary, laboratory monitoring, electrolyte and/or vitamin

Grooten et al. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2016) 16:22

Page 3 of 6

Fig. 1 CONSORT 2010 flow diagram MOTHER trial

supplementation, antiemetic medication and dietetic advice. Type of rehydration regimen, medication and duration of hospitalisation is prescribed according to local

protocol. In case of prolonged hospital admission or readmissions, tube feeding can be initiated at the decision of

the attending physician.

Grooten et al. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2016) 16:22

When allocated to the intervention group, participants

receive a nasogastric tube as soon as possible after randomisation, in addition to standard care. If the initial

nasogastric tube is dislocated or poorly tolerated a nasoduodenal or nasojejunal insertion can also be considered. Tube feeding regimen and mix is prescribed

according to local protocol. As soon as tube feeding is

tolerated and participants have received safety instructions (e.g. recognising symptoms that need to be evaluated in hospital, because of potential tube blockage,

dislocation or aspiration), discharge home with tube

feeding is encouraged under the guidance of a hospital

dietician. Energy intake per tube is continued at least

until the patient is able to maintain an oral intake of

1000 cal per day for one week. According to the NICE

guideline on nutrition, tube feeding in a home setting is

considered to be safe [14].

Data collection

At the day of randomisation, participants fill out a questionnaire. This questionnaire consists of validated NVP

symptom and NVP specific quality of life measures

(24-h Pregnancy Unique Quantification of Emesis and

nausea score, PUQE-24; Hyperemesis Impact of Symptoms questionnaire, HIS; Nausea and Vomiting in Pregnancy Quality of Life questionnaire, NVPQoL) [7, 1921],

psychopathology (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale,

HADS; Symptoms CheckList 90, SCL-90) [2225] and

general health related questions (Short Form 36, SF-36;

EuroQol 5 Dimensions questionnaire,EQ5D) [26, 27].

Participants fill out additional questionnaires (NVPQoL,

HIS, HADS) 1 and 3 weeks after randomisation and record a diary at weekly intervals (PUQE-24, weight, medication use, dietary intake) from randomisation until

20 weeks gestation. If dietary intake has normalised from

15 weeks gestation onwards, this is no longer recorded.

Six weeks postpartum (HADS, SF-36, EQ5D) and

12 months postpartum a final questionnaire is filled out

(HADS, SF-36, EQ5D, SCL-90). See Table 1.

To evaluate potential HG and birth weight predictors,

detailed information on obstetric and medical history,

anthropometrics (before and during pregnancy), antiemetic medication use, given treatment(s) (including

intravenous and/or tube feeding regimen and tube location), laboratory results, treatment and pregnancy complications and birth outcomes are collected using a

standardised Case Report Form (CRF; see Additional

file 1). Research staff obtains the information needed

based on medical and dietician records. Maternal demographics (ethnicity, education level, marital status), mode

of conception and onset of nausea and vomiting symptoms are enquired via the questionnaire.

All participants in this trial are asked for informed

consent of storage of maternal blood (taken with routine

Page 4 of 6

laboratory analysis during hospital admission for HG),

cord blood and placental biopsies (taken at birth) in an obstetrical biobank (the Preeclampsia and Non-preeclampsia

Database, Academic Medical Centre Amsterdam, the

Netherlands). The addition of these samples will enable

molecular studies in HG aetiology and consequences. Furthermore, cord blood will be used for the assessment of

plasma lipids (cholesterol, HDL, LDL, triglycerides, Apolipoprotein A and B), glucose, leptin and thyroid function

(TSH, fT4).

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome will be neonatal birth weight.

Secondary outcome measures

Secondary outcomes will be the validated PUQE-24

score one week after randomisation, maternal weight

gain, dietary intake, HIS, NVPQoL, EQ5D, SF-36, HADS

and SCL-90 scores, urinary ketones, duration of hospital

stay and number of readmissions. Furthermore, gestational age at birth, preterm birth rate, small for gestational

age (SGA; <10th percentile) placental weight, umbilical

cord plasma lipids, neonatal hypoglycaemia, hyperbilirubinaemia and congenital anomalies will be evaluated. Lastly,

we will evaluate maternal side effects of tube feeding and

intravenous rehydration and reasons for discontinuation

of the allocated treatment.

Follow-up of infants

A plan for long-term follow up of children is in preparation, because little is known about the long term health

effects of babies born to mothers whose pregnancies were

complicated by HG and we have reason to hypothesise

that maternal malnutrition during early pregnancy has

long term effects on the offsprings cardiometabolic health

[4]. Funding for follow-up has not yet been obtained.

Statistical issues

Sample size

The sample size is based on a difference in mean birth

weight of 200 g (SD 400 g) between the intervention

group and the control group, which we consider clinically

relevant. With a beta of 0.2 and alpha of 0.05 and a possible 10 % loss to follow up, we need to randomise 120

participants (60 per arm). This sample size is also large

enough to detect a two point reduction in PUQE-24 score

1 week after randomisation (maximum 15 points, SD 3

points) and differences in quality of life, psychopathology

and general health questionnaires 10 %.

Data analysis

Data will be analysed according to the intention to

treat principle. Difference in birth weight will be

Grooten et al. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2016) 16:22

Page 5 of 6

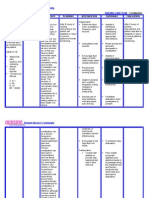

Table 1 Time line MOTHER trial

T0

T1

T2

T3

T4

T5

Randomisation +1 week + 2 weeks + 3 weeks + 4 weeks until GA

20 weeks

T6

Birth 6 weeks postpartum

T7

12 months postpartum

Diary

PUQE

Current weight

Medication use

Dietary intake

Xa

Questionnaires

General health

NVPQoL

HIS

HADS

SF-36

EQ5D

SCL-90

X

X

Biobank material

Maternal blood

Cord blood

Placental

biopsies

PUQE pregnancy unique quantification of emesis and nausea score, NVPQoL nausea and vomiting in pregnancy quality of life questionnaire, HIS hyperemesis impact of

symptoms questionnaire, HADS hospital anxiety and depression scale, SF-36 short form 36, EQ5D euroQol 5 dimensions questionnaire, SCL-90 symptoms checklist 90

a

If dietary intake has normalised from GA 15 weeks onwards, this will be no longer recorded

assessed using parametric testing. PUQE-24 score will

be analysed using multivariate regression and repeated

measurements ANOVA or mixed models, as will be

quality of life assessments. Other secondary outcomes

will be addressed in a similar manner. For nonnormally distributed variables non-parametric equivalents will be used. To evaluate the potential of each

of the strategies, we will also perform a per protocol

analysis, taking into account only those women that

were treated according to protocol.

Discussion

Since HG is the largest cause of hospital admission in

early pregnancy and has major consequences for maternal quality of life, with possible adverse effects on

birth outcomes, evidence based treatment options are

needed. Optimal treatment should be safe, reduce maternal complaints, duration of hospital stay and minimise adverse effects on offspring health. This trial

will provide evidence on these subjects comparing

standard care with intravenous rehydration and early

enteral tube feeding in addition to standard care.

Data safety monitoring committee

Serious Adverse Events (SAEs) are reported to the

Data Safety Monitoring Committee (DSMC). The

DSMC can decide, if indicated, to terminate the trial

prematurely.

Ethical considerations

This trial has been approved by the ethics committee of

the Academic Medical Centre Amsterdam (Reference

number MEC AMC 2012_320) and by the boards of

management of all participating hospitals. The trial is

registered in the Dutch Trial Register, NTR4197, http://

www.trialregister.nl webcite. Date of registration: October

2nd 2013. The full protocol can also be downloaded from

the study website: www.studies-obsgyn.nl/mother.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Case Report Form MOTHER trial. (PDF 252 kb)

Additional file 2: CONSORT 2010 checklist MOTHER trial. (DOCX 48 kb)

Abbreviations

CRF: case report form; EQ5D: euroQol 5 dimensions questionnaire;

HADS: hospital anxiety and depression scale; HG: hyperemesis gravidarum;

HIS: hyperemesis impact of symptoms questionnaire; NICE: National Institute

for Health and Care Excellence; NVP: nausea and vomiting in pregnancy;

NVPQoL: nausea and vomiting in pregnancy quality of life questionnaire;

PUQE-24: 24-h pregnancy unique quantification of emesis and nausea score;

SCL-90: symptoms checklist 90; SF-36: short form 36.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Grooten et al. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2016) 16:22

Authors contributions

RCP, TJR, BWM, JvdP, CRS, JMJB and IJG represent the MOTHER study group

and were involved in conception and design of the study. MK, CJB, JJD, HAB,

MMP, WMH, KWMB, HCJS, MTMF and MAO are local investigators at the

participating centres and participated in the design of the study during

several meetings. IJG, RCP and TJR drafted the manuscript, which follows the

CONSORT 2010 checklist for reporting randomised trials (see Additional file

2). All authors read, edited and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Funding has been obtained from the Dutch Consortium for Studies in

Obstetrics, Fertility and Gynaecology and the Foreest Medical School,

Medical Centre Alkmaar, the Netherlands.

Author details

1

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Academic Medical Centre,

University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 2Department of

Clinical Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Academic Medical

Centre, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 3The

Robinson Institute, School of Paediatrics and Reproductive Health, University

of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia. 4Laboratory of Reproductive Biology,

Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The

Netherlands. 5Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Medical Centre

Alkmaar, Alkmaar, The Netherlands. 6Department of Obstetrics and

Gynaecology, VU Medical Centre, VU University Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The

Netherlands. 7Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Erasmus MC,

Erasmus Medical Centre Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

8

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Reinier de Graaf Hospital, Delft,

The Netherlands. 9Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Mxima

Medical Centre, Veldhoven, The Netherlands. 10Department of Obstetrics and

Gynaecology, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The

Netherlands. 11Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Leiden University

Medical Centre, Leiden, The Netherlands. 12Department of Obstetrics and

Gynaecology, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, The

Netherlands. 13Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University

Medical Centre Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Received: 9 July 2014 Accepted: 25 January 2016

References

1. Matthews A, Haas DM, OMathuna DP, Dowswell T, Doyle M. Interventions

for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2014;3:CD007575.

2. Niebyl JR. Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:154450.

3. Bailit JL. Hyperemesis gravidarium: epidemiologic findings from a large

cohort. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:8114.

4. Veenendaal MVE, van Abeelen AFM, Painter RC, van der Post JAM,

Roseboom TJ. Consequences of hyperemesis gravidarum for offspring: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2011;118:130213.

5. Smith C, Crowther C, Beilby J, Dandeaux J. The impact of nausea and

vomiting on women: a burden of early pregnancy. Aust N Z J Obstet

Gynaecol. 2000;40:397401.

6. Lacasse A, Rey E, Ferreira E, Morin C, Brard A. Nausea and vomiting of

pregnancy: what about quality of life? BJOG. 2008;115:148493.

7. Lacasse A, Berard A. Validation of the nausea and vomiting of pregnancy

specific health related quality of life questionnaire. Health Qual Life

Outcomes. 2008;6:32.

8. Adams MM, Harlass FE, Sarno AP, Read JA, Rawlings JS. Antenatal hospitalization

among enlisted servicewomen, 1987-1990. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:359.

9. Gazmararian JA, Petersen R, Jamieson DJ, Schild L, Adams MM, Deshpande AD,

et al. Hospitalizations during pregnancy among managed care enrollees.

Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:94100.

10. Verberg MFG, Gillott DJ, Al-Fardan N, Grudzinskas JG. Hyperemesis

gravidarum, a literature review. Hum Reprod Update. 2005;11:52739.

11. Sandven I, Abdelnoor M, Wethe M, Nesheim B-I, Vikanes , Gjnnes H, et al.

Helicobacter pylori infection and hyperemesis gravidarum. An institutionbased casecontrol study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2008;23:4918.

12. Jueckstock JK, Kaestner R, Mylonas I. Managing hyperemesis gravidarum: a

multimodal challenge. BMC Med. 2010;8:46.

Page 6 of 6

13. Stokke G, Gjelsvik BL, Flaatten KT, Birkeland E, Flaatten H, Trovik J.

Hyperemesis gravidarum, nutritional treatment by nasogastric tube

feeding: a 10-year retrospective cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol

Scand. 2015;94:35967.

14. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Nutrition support in

adults: NICE guideline CG32. London: NICE Clinical Guidelines; 2006.

15. Holmgren C, Silver RM, Porter TF, Varner M, Aagaard-Tillery KM. Hyperemesis

in pregnancy: an evaluation of treatment strategies with maternal and

neonatal outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:56. e156.e4.

16. Gulley RM, Vander Pleog N, Gulley JM. Treatment of hyperemesis

gravidarum with nasogastric feeding. Nutr Clin Pr. 1993;8:335.

17. Hsu JJ, Clark-Glena R, Nelson DK, Kim CH. Nasogastric enteral feeding in the

management of hyperemesis gravidarum. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:3436.

18. Pearce CB, Collett J, Goggin PM, Duncan HD. Enteral nutrition by

nasojejunal tube in hyperemesis gravidarum. Clin Nutr. 2001;20:4614.

19. Koren G, Boskovic R, Hard M, Maltepe C, Navioz Y, Einarson A. MotheriskPUQE (pregnancy-unique quantification of emesis and nausea) scoring

system for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;

186(5 Suppl Understanding):S22831.

20. Magee LA, Chandra K, Mazzotta P, Stewart D, Koren G, Guyatt GH.

Development of a health-related quality of life instrument for nausea and

vomiting of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:S2328.

21. Power Z, Campbell M, Kilcoyne P, Kitchener H, Waterman H. The

hyperemesis impact of symptoms questionnaire: development and

validation of a clinical tool. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;47:6777.

22. Derogatis LR. SCL-90: an outpatient psychiatric rating scalepreliminary

report. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1973;9:1328.

23. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta

Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:36170.

24. Spinhoven P, Ormel J, Sloekers PP, Kempen GI, Speckens AE, Van Hemert

AM. A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychol Med. 1997;27:36370.

25. Arrindell WA, Ettema JHM: SCL-90 (symptom checklist 90). Handleiding Bij Een

multidimensionele psychopathologie-indicator. Lisse; Swets Test Publishers 2003.

26. The EuroQoL Group. EuroQol - a new facility for the measurement of

health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199208.

27. Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Grandek B. SF-36 health survey: manual and

interpretation guide. Boston, MA; The Health Institute, New England Medical

Center 1993.

Submit your next manuscript to BioMed Central

and we will help you at every step:

We accept pre-submission inquiries

Our selector tool helps you to find the most relevant journal

We provide round the clock customer support

Convenient online submission

Thorough peer review

Inclusion in PubMed and all major indexing services

Maximum visibility for your research

Submit your manuscript at

www.biomedcentral.com/submit

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Konstantopoulos 2020Document14 pagesKonstantopoulos 2020Corey WoodsPas encore d'évaluation

- Early Total Enteral Feeding in Stable Very Low Birth Weight Infants: A Before and After StudyDocument7 pagesEarly Total Enteral Feeding in Stable Very Low Birth Weight Infants: A Before and After StudySupriya M A SuppiPas encore d'évaluation

- Effect of Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment On Gastrointestinal Function and Length of Stay of Preterm Infants: An Exploratory StudyDocument6 pagesEffect of Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment On Gastrointestinal Function and Length of Stay of Preterm Infants: An Exploratory StudySandro PerilloPas encore d'évaluation

- HG Case StudyDocument12 pagesHG Case StudyleehiPas encore d'évaluation

- Gaviscon ClinicalDocument7 pagesGaviscon ClinicalMuhammad Nadzri NoorhayatuddinPas encore d'évaluation

- The Treatment of Booking Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (TOBOGM) Pilot Randomised Controlled TrialDocument8 pagesThe Treatment of Booking Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (TOBOGM) Pilot Randomised Controlled Trialdhea handyaraPas encore d'évaluation

- 2016 June Case StudyDocument8 pages2016 June Case StudyMarius Clifford BilledoPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal Prakonsepsi RCTDocument10 pagesJurnal Prakonsepsi RCTnorberta aldaPas encore d'évaluation

- Expectant Versus Aggressive Management in Severe Preeclampsia Remote From TermDocument6 pagesExpectant Versus Aggressive Management in Severe Preeclampsia Remote From Termmiss.JEJEPas encore d'évaluation

- Obstetric Research Journal DayandanteDocument4 pagesObstetric Research Journal DayandanteKrizelle MesinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Risks Associated With Obesity in Pregnancy (Final Accepted Version)Document47 pagesRisks Associated With Obesity in Pregnancy (Final Accepted Version)SamarPas encore d'évaluation

- Nakimuli2016 Article TheBurdenOfMaternalMorbidityAnDocument8 pagesNakimuli2016 Article TheBurdenOfMaternalMorbidityAnPriscilla AdetiPas encore d'évaluation

- PYMS TamizajeDocument6 pagesPYMS TamizajeKevinGallagherPas encore d'évaluation

- Optimal Timing For Introducing Enteral Nutrition in The Neonatal Intensive Care UnitDocument8 pagesOptimal Timing For Introducing Enteral Nutrition in The Neonatal Intensive Care UnitAnonymous 1EQutBPas encore d'évaluation

- Acid Jurnal 4Document7 pagesAcid Jurnal 4awaloeiacidPas encore d'évaluation

- Smo 3Document6 pagesSmo 3Irini BogiagesPas encore d'évaluation

- Original Research Paper: Dr. UmaDocument3 pagesOriginal Research Paper: Dr. UmaOviya ChitharthanPas encore d'évaluation

- Role of Gastric Lavage in Newborn With Meconium Stained Amniotic Fluid:a Randomized Controlled TrailDocument3 pagesRole of Gastric Lavage in Newborn With Meconium Stained Amniotic Fluid:a Randomized Controlled TrailtriaanggareniPas encore d'évaluation

- Original Research PaperDocument4 pagesOriginal Research PaperOviya ChitharthanPas encore d'évaluation

- BMJ f6398Document13 pagesBMJ f6398Luis Gerardo Pérez CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Referat 7Document9 pagesReferat 7Sultan Rahmat SeptianPas encore d'évaluation

- Leitich, 2003 Antibiotico No Tratamento de VB Meta AnaliseDocument7 pagesLeitich, 2003 Antibiotico No Tratamento de VB Meta AnaliseEdgar SimmonsPas encore d'évaluation

- Fast Hug FaithDocument4 pagesFast Hug FaithHenrique Yuji Watanabe SilvaPas encore d'évaluation

- Maternal and Perinatal Maternal and Perinatal Outcome of Maternal Obesity Outcome of Maternal Obesity at RSCM in 2014-2019 at RSCM in 2014-2019Document1 pageMaternal and Perinatal Maternal and Perinatal Outcome of Maternal Obesity Outcome of Maternal Obesity at RSCM in 2014-2019 at RSCM in 2014-2019heidi leePas encore d'évaluation

- Acute Pyelonephritis in PregnancyDocument7 pagesAcute Pyelonephritis in PregnancyKvmLlyPas encore d'évaluation

- Obesidad y EmbarazoDocument5 pagesObesidad y EmbarazolandaburePas encore d'évaluation

- KolestasisDocument10 pagesKolestasisNur Ainatun NadrahPas encore d'évaluation

- The Prevalence and Complications of Urinary Tract Infections in Women With Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Facts and FantasiesDocument4 pagesThe Prevalence and Complications of Urinary Tract Infections in Women With Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Facts and FantasiesFahmi Afif AlbonehPas encore d'évaluation

- HHS Public Access: Folic Acid Supplementation and Dietary Folate Intake, and Risk of PreeclampsiaDocument15 pagesHHS Public Access: Folic Acid Supplementation and Dietary Folate Intake, and Risk of PreeclampsiaDevi KharismawatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Women's Breastfeeding Experiences Following A Significant Primary Postpartum Haemorrhage: A Multicentre Cohort StudyDocument12 pagesWomen's Breastfeeding Experiences Following A Significant Primary Postpartum Haemorrhage: A Multicentre Cohort StudyMigumi YoshugaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Gastrointestinal and Liver Disorders in Women’s Health: A Point of Care Clinical GuideD'EverandGastrointestinal and Liver Disorders in Women’s Health: A Point of Care Clinical GuidePoonam Beniwal-PatelPas encore d'évaluation

- The Inverted Syringe Technique For Management of I PDFDocument9 pagesThe Inverted Syringe Technique For Management of I PDFAri SapitriPas encore d'évaluation

- Napro Ireland 2008Document10 pagesNapro Ireland 2008Poliklinika LAB PLUSPas encore d'évaluation

- Nutrients: Complications Associated With Enteral Nutrition: CAFANE StudyDocument12 pagesNutrients: Complications Associated With Enteral Nutrition: CAFANE StudySiti WarohmahPas encore d'évaluation

- Hyperglycaemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) Study: Associations With Maternal Body Mass IndexDocument10 pagesHyperglycaemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) Study: Associations With Maternal Body Mass Indexdr.vidhyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Medi 102 E33898Document7 pagesMedi 102 E33898ade lydia br.siregarPas encore d'évaluation

- Mothers With Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy Increased Risk of Periventricular Leukomalacia in Extremely Preterm or Extremely Low Birth Weight Infants A Propensity Score AnalysisDocument9 pagesMothers With Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy Increased Risk of Periventricular Leukomalacia in Extremely Preterm or Extremely Low Birth Weight Infants A Propensity Score Analysisnurt.wongPas encore d'évaluation

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 10: ObstetricsD'EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 10: ObstetricsPas encore d'évaluation

- Frequency of Surgery in Patients With Ectopic Pregnancy After Treatment With MethotrexateDocument5 pagesFrequency of Surgery in Patients With Ectopic Pregnancy After Treatment With Methotrexatetomas edibaPas encore d'évaluation

- Thesis Complete PDFDocument217 pagesThesis Complete PDFArum WinantuPas encore d'évaluation

- Efectele Pe Termen Lung Ale Alaptatului OMSDocument74 pagesEfectele Pe Termen Lung Ale Alaptatului OMSbobocraiPas encore d'évaluation

- Embarazo EctópicoDocument7 pagesEmbarazo EctópicomariPas encore d'évaluation

- Does Cow S Milk Protein Elimination Diet Have A Role On Induction and MaintenanceDocument6 pagesDoes Cow S Milk Protein Elimination Diet Have A Role On Induction and MaintenanceNejc KovačPas encore d'évaluation

- Different Modalities in First Stage Enhancement of LaborDocument4 pagesDifferent Modalities in First Stage Enhancement of LaborTI Journals PublishingPas encore d'évaluation

- The Effects of Premature Infant Oral Motor Intervention (PIOMI) On Oral Feeding of Preterm Infants - A Randomized Clinical TrialDocument8 pagesThe Effects of Premature Infant Oral Motor Intervention (PIOMI) On Oral Feeding of Preterm Infants - A Randomized Clinical TrialAndreas Arie WidiadiaksaPas encore d'évaluation

- 02 - Aims of Obstetric Critical Care ManagementDocument25 pages02 - Aims of Obstetric Critical Care ManagementAlberto Kenyo Riofrio PalaciosPas encore d'évaluation

- Fucile2018 Ver WordDocument8 pagesFucile2018 Ver WordAries CamiPas encore d'évaluation

- Paediatrica Indonesiana: Original ArticleDocument5 pagesPaediatrica Indonesiana: Original Articlemelanita_99Pas encore d'évaluation

- JurnalDocument7 pagesJurnalEko WidodoPas encore d'évaluation

- Scientific Advisory Committee Opinion Paper 23: 1. BackgroundDocument5 pagesScientific Advisory Committee Opinion Paper 23: 1. BackgroundNatia DemetradzePas encore d'évaluation

- Journal of Pediatric Surgery: Wendy K. Fujioka, Robert A. CowlesDocument3 pagesJournal of Pediatric Surgery: Wendy K. Fujioka, Robert A. CowlesVmiguel LcastilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Ojog 2016092215550796Document8 pagesOjog 2016092215550796Anonymous OHYEGAhzsPas encore d'évaluation

- Pediatrics 2012 Aja NieDocument7 pagesPediatrics 2012 Aja NiePutu BudiastawaPas encore d'évaluation

- Effects of Acupuncture On Preeclampsia in Chinese Women: A Pilot Prospective Cohort StudyDocument5 pagesEffects of Acupuncture On Preeclampsia in Chinese Women: A Pilot Prospective Cohort StudyJayanti IndrayaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Aims of Obstetric Critical Care Management 160303161653 PDFDocument25 pagesAims of Obstetric Critical Care Management 160303161653 PDFNinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lactose Intolerance Among Severely Malnourished Children With Diarrhoea Admitted To The Nutrition Unit, Mulago Hospital, UgandaDocument9 pagesLactose Intolerance Among Severely Malnourished Children With Diarrhoea Admitted To The Nutrition Unit, Mulago Hospital, UgandaArsy Mira PertiwiPas encore d'évaluation

- Journal of Nursing Science - Benha University: JnsbuDocument15 pagesJournal of Nursing Science - Benha University: JnsbuBADLISHAH BIN MURAD MoePas encore d'évaluation

- Journal Reading Diet Sebelum Kehamilan Dan Risiko Hiperemesis GravidarumDocument23 pagesJournal Reading Diet Sebelum Kehamilan Dan Risiko Hiperemesis GravidarumNalendra Tri WidhianartoPas encore d'évaluation

- Acute Gastroenteritis in Children of The World: What Needs To Be Done?Document8 pagesAcute Gastroenteritis in Children of The World: What Needs To Be Done?yoonie catPas encore d'évaluation

- Bms BLACKBOOK Project EditedDocument76 pagesBms BLACKBOOK Project Editedaltafk7972Pas encore d'évaluation

- Nutrition Care ProcessDocument6 pagesNutrition Care ProcessGeraldine MaePas encore d'évaluation

- Wild Fermentation, 2nd Edition - ForewordDocument2 pagesWild Fermentation, 2nd Edition - ForewordChelsea Green PublishingPas encore d'évaluation

- 1-Kelley's Cancer Therapy - This Is The Cure For CancerDocument11 pages1-Kelley's Cancer Therapy - This Is The Cure For CancerSusyary S100% (2)

- Nursing: A Concept-Based Approach To Learning: Volume One, Third EditionDocument32 pagesNursing: A Concept-Based Approach To Learning: Volume One, Third EditionSamip PatelPas encore d'évaluation

- Chocolate: by Jessica SpenceDocument12 pagesChocolate: by Jessica SpenceValéria Oliveira100% (1)

- Lab Report Measuring DietDocument26 pagesLab Report Measuring DietNur Izzah AnisPas encore d'évaluation

- NCM105AR Lab Group 2 Nutrition Care Plan PDFDocument6 pagesNCM105AR Lab Group 2 Nutrition Care Plan PDFKIMBERLY CABATOPas encore d'évaluation

- Concise Selina Biology Part I Solution For Class 9 Biology Chapter 11Document6 pagesConcise Selina Biology Part I Solution For Class 9 Biology Chapter 11Nehaa MankaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Diet JourneyDocument10 pagesDiet JourneyEllyPas encore d'évaluation

- Natures Hidden Health MiracleDocument38 pagesNatures Hidden Health MiracleGorneau100% (2)

- Nutritional Considerations For Healthy Aging and Reduction in Age-Related Chronic DiseaseDocument10 pagesNutritional Considerations For Healthy Aging and Reduction in Age-Related Chronic DiseaseSilvana RamosPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 1 FinalDocument9 pagesChapter 1 FinalEmmanuel PlazaPas encore d'évaluation

- General Standard For The Labelling of Prepackaged FoodDocument9 pagesGeneral Standard For The Labelling of Prepackaged FoodAubreyPas encore d'évaluation

- Nutraceuticals Leaflet ENGDocument2 pagesNutraceuticals Leaflet ENGDr. Dragos CobzariuPas encore d'évaluation

- GheeDocument11 pagesGheeLakshmi Kanthan BharathiPas encore d'évaluation

- Gerd AdimeDocument2 pagesGerd Adimeapi-301716754100% (2)

- Bahasa Inggris SMP/MTS: Text For Questions Number 1 - 2Document9 pagesBahasa Inggris SMP/MTS: Text For Questions Number 1 - 2Andri YuliprasetioPas encore d'évaluation

- Leaky Gut Syndrome in Plain English - and How To Fix It - SCD LifestyleDocument81 pagesLeaky Gut Syndrome in Plain English - and How To Fix It - SCD Lifestylemusatii50% (4)

- Share 'FINAL RRL (Autosaved) 2Document22 pagesShare 'FINAL RRL (Autosaved) 2Jeanelle DenostaPas encore d'évaluation

- Nursing Care Plan - ConstipationDocument2 pagesNursing Care Plan - Constipationderic87% (71)

- A Nutrition and Conditioning Intervention For Natural Bodybuilding Contest Preparation: Case StudyDocument12 pagesA Nutrition and Conditioning Intervention For Natural Bodybuilding Contest Preparation: Case StudyTHIMMAPPAPas encore d'évaluation

- PE 101 FinalsDocument23 pagesPE 101 FinalsHazel EspañolaPas encore d'évaluation

- Marketing Plan 2019: A Filipino Junk-Free Snack CompanyDocument19 pagesMarketing Plan 2019: A Filipino Junk-Free Snack CompanyDarie Shaine Sulivan GayacanPas encore d'évaluation

- Form 2 Chapter 3 NutritionDocument68 pagesForm 2 Chapter 3 NutritionAmer MalekPas encore d'évaluation

- O6-ApiHealth Handbook EN FinalDocument195 pagesO6-ApiHealth Handbook EN FinallucaemigrantePas encore d'évaluation

- NDT Lec Vitamins and MineralsDocument18 pagesNDT Lec Vitamins and MineralsCrystal MaidenPas encore d'évaluation

- COMS291 Powerpoint 10Document6 pagesCOMS291 Powerpoint 10GuruPas encore d'évaluation

- Big Cunnie Energy Recipe BookDocument51 pagesBig Cunnie Energy Recipe Bookjoelle Fidler100% (1)

- Referat Compusi Biologic ActiviDocument56 pagesReferat Compusi Biologic ActiviAna-Maria SiminescuPas encore d'évaluation