Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Superintendent of Five Civilized Tribes v. Commissioner, 295 U.S. 418 (1935)

Transféré par

Scribd Government DocsCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Superintendent of Five Civilized Tribes v. Commissioner, 295 U.S. 418 (1935)

Transféré par

Scribd Government DocsDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

295 U.S.

418

55 S.Ct. 820

79 L.Ed. 1517

SUPERINTENDENT OF FIVE CIVILIZED TRIBES, FOR

SANDY FOX, CREEK NO. 1263,

v.

COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE.

No. 817.

Argued May 6, 7, 1935.

Decided May 20, 1935.

Messrs. Thomas J. Reilly and Arthur F. Mullen, both of Washington,

D.C., for petitioner.

The Attorney General and Frank J. Wideman, Asst. Atty. Gen., for

respondent.

Mr. Justice McREYNOLDS delivered the opinion of the Court.

Sandy Fox, for whom this suit was instituted, is a full-blood Creek Indian.

Certain funds, said to have been derived from his restricted allotment, in excess

of his needs were invested. The proceeds therefrom were collected and held in

trust under direction of the Secretary of Interior. The question now presented is

whether this income was subject to the federal tax laid by the 1928 Revenue

Act (chapter 852, 11, 12, 45 Stat. 791, 26 USCA 2011, 2012). The

Commissioner, the Board of Tax Appeals, and the court below answered in the

affirmative.

Petitioner maintains that the court should have followed the rule which it

applied in Blackbird v. Commissioner (C.C.A.) 38 F.(2d) 976, 977; also that it

erroneously held Congress intended to tax income derived from investment of

funds arising from restricted lands belonging to a full-blood Creek Indian.

Blackbird, restricted full-blood Osage, maintained that she was not subject to

the federal income tax statute. The court sustained that view and declared:

'Her property is under the supervising control of the United States. She is its

ward, and we cannot agree that because the income statute, Act of 1918 (40

Stat. 1057), and Act of 1921 (42 Stat. 227), subjects 'the net income of every

individual' to the tax, this is alone sufficient to make the Acts applicable to her.

Such holding would be contrary to the almost unbroken policy of Congress in

dealing with its Indian wards and their affairs. Whenever they and their

interests have been the subject affected by legislation they have been named

and their interests specifically dealt with.'

This does not harmonize with what we said in Choteau v. Burnet (1931) 283

U.S. 691, 693, 696, 51 S.Ct. 598, 600, 75 L.Ed. 1353:

'The language of sections 201 and 211(a) (Revenue Act 1918) subjects the

income of 'every individual' to tax. Section 213(a) includes income 'from any

source whatever.'1 The intent of Congress was to levy the tax with respect to all

residents of the United States and upon all sorts of income. The act does not

expressly exempt the sort of income here involved, nor a person having

petitioner's status respecting such income, and we are not referred to any other

statute which does. * * * The intent to exclude must be definitely expressed,

where, as here, the general language of the act laying the tax is broad enough to

include the subject-matter.'

The court below properly declined to follow its quoted pronouncement in

Blackbird's Case. The terms of the 1928 Revenue Act are very broad, and

nothing there indicates that Indians are to be excepted. See Irwin v. Gavit, 268

U.S. 161, 45 S.Ct. 475, 69 L.Ed. 897; Heiner v. Colonial Trust Co., 275 U.S.

232, 48 S.Ct. 65, 72 L.Ed. 256; Helvering v. Stockholms, etc., Bank, 293 U.S.

84, 55 S.Ct. 50, 79 L.Ed. 211; Pitman v. Commissioner (C.C.A.) 64 F.(2d) 740.

The purpose is sufficiently clear.

It is affirmed that 'inalienability and nontaxability go hand in hand; and that it is

not lightly to be assumed that Congress intended to tax the ward for the benefit

of the guardian.'

The general terms of the taxing act include the income under consideration and

if exemption exists it must derive plainly from agreements with the Creeks or

some act of Congress dealing with their affairs.

10

Neither the Creek agreement of 1901 (31 Stat. 861), nor the Supplemental

Agreement of 1902 (32 Stat. 500), conferred general exemption from taxation

upon Indians; homesteads only were definitely excluded, although alienation of

allotted lands was restricted.

11

The suggestion that exemption must be inferred from the Act of April 26, 1906

(34 Stat. 137) or Act of May 27, 1908 (35 Stat. 312) is not well founded. The

first of these extended restrictions upon the alienation of allotments for twentyfive years unless sooner removed by Congress, and provided: 'Sec. 19. * * *

That all lands upon which restrictions are removed shall be subject to taxation,

and the other lands shall be exempt from taxation as long as the title remains in

the original allottee.' This exemption related to land and not to income derived

from investment of surplus income from land. Moreover, the act itself was

superseded by the second one which did not contain the quoted provision, but

declared: 'Sec. 4. That all land from which restrictions have been or shall be

removed shall be subject to taxation and all other civil burdens as though it

were the property of other persons than allottees of the Five Civilized Tribes. *

* *'

12

We find nothing in either act which expresses definite intent to exclude from

taxation such income as that here involved. See Shaw v. Gibson-Zahniser Oil

Corp., 276 U.S. 575, 581, 48 S.Ct. 333, 72 L.Ed. 709.

13

Nor can we conclude that taxation of income from trust funds of an Indian ward

is so inconsistent with that relationship that exemption is a necessary

implication. Non-taxability and restriction upon alienation are distinct things.

Choate v. Trapp, 224 U.S. 665, 673, 32 S.Ct. 565, 56 L.Ed. 941. The taxpayer

here is a citizen of the United States, and wardship with limited power over his

property does not, without more, render him immune from the common burden.

14

Shaw v. Gibson-Zahniser Oil Corp., supra, held that restricted land purchased

for a full-blood Creekward of the United Stateswith trust funds was not

free from state taxation, and declared that such exemption could not be implied

merely because of the restrictions upon the Indian's power to alienate.

15

Affirmed.

Like provisions are in sections 210 and 211(a), Revenue Acts 1921, 1924, 1926

(26 USCA 951, 952 notes), and sections 11 and 12(a), Revenue Act 1928

(26 USCA 2011, 2012(a); section 213(a), Revenue Acts 1921, 1924, 1926

(26 USCA 954(a) and note), and section 22, Revenue Act 1928 (26 USCA

2022).

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Northern New Mexicans v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthern New Mexicans v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Chevron Mining v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Document42 pagesChevron Mining v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Robles v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesRobles v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Jimenez v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesJimenez v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Coburn v. Wilkinson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesCoburn v. Wilkinson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Parker Excavating v. LaFarge West, 10th Cir. (2017)Document24 pagesParker Excavating v. LaFarge West, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- McGarry v. Bucket Innovations - ComplaintDocument23 pagesMcGarry v. Bucket Innovations - ComplaintSarah BursteinPas encore d'évaluation

- Intestate Estate of ARSENIO R. AFAN. MARIAN AFAN, Petitioner-Appellee, Vs - APOLINARIO S. DE GUZMANDocument42 pagesIntestate Estate of ARSENIO R. AFAN. MARIAN AFAN, Petitioner-Appellee, Vs - APOLINARIO S. DE GUZMANMaris Angelica Ayuyao100% (1)

- SG Fire Safety ActDocument78 pagesSG Fire Safety ActPerie Anugraha WigunaPas encore d'évaluation

- Tourist Visa Us MinorDocument3 pagesTourist Visa Us MinorpreethiPas encore d'évaluation

- Agreement Paper For Internal AuditDocument2 pagesAgreement Paper For Internal AuditSubashSangraulaPas encore d'évaluation

- CA's (SA) - Commissioner of OathsDocument3 pagesCA's (SA) - Commissioner of OathsCharles ArnestadPas encore d'évaluation

- Alliance University: Procedure For Provisional Admission To The MBA Course: Fall 2016 BatchDocument2 pagesAlliance University: Procedure For Provisional Admission To The MBA Course: Fall 2016 BatchGaurav GoelPas encore d'évaluation

- Oblicon CasesDocument58 pagesOblicon CasesKris Jonathan CrisostomoPas encore d'évaluation

- Information For Qualified TheftDocument2 pagesInformation For Qualified TheftMarvin H. Taleon II100% (7)

- Pre-Trial brief-BPIvsasuncion-collection-metc Mkti 63Document6 pagesPre-Trial brief-BPIvsasuncion-collection-metc Mkti 63George MelitsPas encore d'évaluation

- People Vs CoronelDocument4 pagesPeople Vs CoronelElias IbarraPas encore d'évaluation

- Domingo Vs Sheer - Strong Family Ties JurisDocument25 pagesDomingo Vs Sheer - Strong Family Ties JurisGerald MesinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ong Chua v. CarrDocument2 pagesOng Chua v. CarrNorberto Sarigumba IIIPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample Judicial AffDocument5 pagesSample Judicial AffTrinca DiplomaPas encore d'évaluation

- Expungement Va LawDocument2 pagesExpungement Va LawJS100% (1)

- All Kinds of Diplomatic NoteDocument90 pagesAll Kinds of Diplomatic NoteMarius C. Mitrea60% (5)

- USA V Warnagiris January 5 2022 Motion by USADocument5 pagesUSA V Warnagiris January 5 2022 Motion by USAFile 411Pas encore d'évaluation

- Santa Ana, PampangaDocument2 pagesSanta Ana, PampangaSunStar Philippine NewsPas encore d'évaluation

- IE Mumbai 08 - 080520135224Document15 pagesIE Mumbai 08 - 080520135224TomPas encore d'évaluation

- Watson Et Al v. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Complaint 2-22-2021Document158 pagesWatson Et Al v. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Complaint 2-22-2021Lucas Manfredi100% (1)

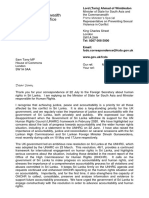

- Letter From Lord Ahmad of Wimbledon To Sam Tarry MP 05082021Document2 pagesLetter From Lord Ahmad of Wimbledon To Sam Tarry MP 05082021Thavam RatnaPas encore d'évaluation

- Manuel vs. PeopleDocument2 pagesManuel vs. PeopleAtty Ed Gibson BelarminoPas encore d'évaluation

- Freedom Fighter Fasc Il I Ties 2012Document170 pagesFreedom Fighter Fasc Il I Ties 2012Kaushik PkaushikPas encore d'évaluation

- Contracts: I. General ProvisionsDocument9 pagesContracts: I. General ProvisionsbchiefulPas encore d'évaluation

- Kasulatan NG UpaDocument2 pagesKasulatan NG UpaJOANA JOANAPas encore d'évaluation

- Mayo, Et Al.) For Unlawful Detainer, Damages, Injunction, Etc., An Appealed Case From TheDocument4 pagesMayo, Et Al.) For Unlawful Detainer, Damages, Injunction, Etc., An Appealed Case From TheRian Lee TiangcoPas encore d'évaluation

- Annotated BibliographyDocument3 pagesAnnotated Bibliographyapi-318100069Pas encore d'évaluation

- Villaber Vs COMELECDocument2 pagesVillaber Vs COMELECLeah Marie Sernal100% (3)

- Vigilant Enterprise Service Agreement With Pinellas County SheriffDocument13 pagesVigilant Enterprise Service Agreement With Pinellas County SheriffJames McLynasPas encore d'évaluation

- 2016 SEC Rules of ProcedureDocument53 pages2016 SEC Rules of ProcedureRemy Rose AlegrePas encore d'évaluation