Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Stephen Mesarosh, Also Known As Steve Nelson v. United States, 352 U.S. 808 (1956)

Transféré par

Scribd Government DocsTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Stephen Mesarosh, Also Known As Steve Nelson v. United States, 352 U.S. 808 (1956)

Transféré par

Scribd Government DocsDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

352 U.S.

808

77 S.Ct. 14

1 L.Ed.2d 39

Stephen MESAROSH, also known as Steve Nelson, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

UNITED STATES of America.

No. 20.

Supreme Court of the United States

October 8, 1956

Solicitor General Rankin and Assistant Attorney General Tompkins, for

the United States.

Messrs. Frank J. Donner, Arthur Kinoy, Marshall Perlin and Hubert T.

Delany, for petitioners.

Mr. Justice FRANKFURTER.

Less than six months ago, in Communist Party v. Subversive Activities Control

Board, 351 U.S. 115, 76 S.Ct. 663, a case that raised important constitutional

issues, this Court refused to pass on those issues when newly discovered

evidence was alleged to demonstrate that the record out of which those issues

arose was tainted. It did so in the following language:

'When uncontested challenge is made that a finding of subversive design by

petitioner was in part the product of three perjurious witnesses, it does not

remove the taint for a reviewing court to find that there is ample innocent

testimony to support the Board's findings. If these witnesses in fact committed

perjury in testifying in other cases on subject matter substantially like that of

their testimony in the present proceedings, their testimony in this proceeding is

inevitably discredited and the Board's determination must duly take this fact

into account. We cannot pass upon a record containing such challenged

testimony. * * *' 351 U.S. at pages 124125, 76 S.Ct. at page 668.

The Court, in that case over the protest of the Government, remanded the

proceedings to the Subversive Activities Control Board so that it might consider

the allegations against the witnesses and, if necessary, reassess the evidence

purged of taint.

In this case, the Government itself has presented a motion to remand the case,

alleging that one of its witnesses, Joseph Mazzei, since he testified in this case,

'has given certain sworn testimony (before other tribunals) which the

Government, on the basis of the information in its possession, now has serious

reason to doubt.' Some of the occurrences on which the motion is based go back

to 1953. (It should be noted that the petition for certiorari was filed in this

Court on October 6, 1955.) Thus the action by the Government at this time may

appear belated. This is irrelevant to the disposition of this motion. The fact is

that the history of Mazzei's post-trial testimony did not come to the Solicitor

General's notice until less than ten days before the presentation of this motion.*

It would, I believe, have been a disregard of the responsibility of the law officer

of the Government especially charged with representing the Government before

this Court not to bring these disturbing facts to the Court's attention once they

came to his attention. And so, it would be unbecoming to speak of the candor of

the Solicitor General in submitting these facts to the Court by way of a formal

motion for remand. It ought to be assumed that a Solicitor General would do

this as a matter of course.

The Government in its motion sets forth the facts which lead it to urge remand.

The Government lists five incidents of testimony by Mazzei between 1953 and

1956 about the activities of alleged Communists and about his own activities in

behalf of the Federal Bureau of Investigation which it now 'has serious reason

to doubt.' The Government also notes that in the trial of this case, Mazzei 'gave

testimony which directly involved two of the petitioners, Careathers and

Dolsen.' Although the Government maintains 'that the testimony given by

Mazzei at the trial was entirely truthful and credible,' it deems the incidents it

sets forth so significant that it asks that the issue of Mazzei's truthfulness be

determined by the District Court after a hearing such as was held in a similar

situation in United States v. Flynn, D.C., 130 F.Supp. 412.

How to dispose of the Government's motion raises a question of appropriate

judicial procedure. The Court has concluded not to pass on the Solicitor

General's motion at this time. It retains the motion to be heard at the outset of

the argument of the case as heretofore set down. I deem it a more appropriate

procedure that the motion be granted forthwith, with directions to the district

Court to hear the issues raised by this motion. I feel it incumbent to state the

reasons for this conviction. Argument can hardly disclose further information

on which to base a decision on the motion. Furthermore, there may be

controversy over the facts, and the judicial methods for sifting controverted

facts are not available here. The basic principle of the Communist Party case

that allegations of tainted testimony must be resolved before this Court will

pass on a case is decisive. Indeed, the situation here is an even stronger one for

application of that principle, for we have before us a statement by the

Government that it 'now has serious reason to doubt' testimony given in other

proceedings by Mazzei, one of its specialists on Communist activities, and a

further statement by the Government that Mazzei's testimony in this case

'directly involved two of the petitioners.'

7

This Court should not even hypothetically assume the trustworthiness of the

evidence in order to pass on other issues. There is more at stake here even than

affording guidance for the District Court in this particular case. This Court

should not pass on a record containing unresolved allegations of tainted

testimony. The integrity of the judicial process is at stake. The stark issue of

rudimentary morality in criminal prosecutions should not be lost in the melange

of more than a dozen other issues presented by petitiioners. And the importance

of thus vindicating the scrupulous administration of justice as a continuing

process far outweighs the disadvantage of possible delay in the ultimate

disposition of this case. The case should be remanded now for a hearing before

the trial judge.

The motion for remand states: 'The complete details of Mazzei's testimony in

Florida, as set forth in this motion, did not come to the attention of the

Department of Justice until September 1956, and the history of Mazzei's posttrial testimony did not come to the Solicitor General's attention until less than

ten days ago.'

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Hale v. Henkel, 201 U.S. 43 (1906)Document27 pagesHale v. Henkel, 201 U.S. 43 (1906)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- An Inexplicable Deception: A State Corruption of JusticeD'EverandAn Inexplicable Deception: A State Corruption of JusticePas encore d'évaluation

- Costello v. United States, 350 U.S. 359 (1956)Document5 pagesCostello v. United States, 350 U.S. 359 (1956)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Fontaine, 106 F.3d 383, 1st Cir. (1997)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Fontaine, 106 F.3d 383, 1st Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- In Re Sawyer, 360 U.S. 622 (1959)Document35 pagesIn Re Sawyer, 360 U.S. 622 (1959)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Anthony Ray Jenkins v. State of Kansas, Don L. Scott, (NFN) Wilson, (NFN) Olson, 66 F.3d 338, 10th Cir. (1995)Document3 pagesAnthony Ray Jenkins v. State of Kansas, Don L. Scott, (NFN) Wilson, (NFN) Olson, 66 F.3d 338, 10th Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Joseph Kuzma, Joseph Roberts, Benjamin Weiss, David Davis, Thomas Nabried, Irvin Katz, Walter Lowenfels, Sherman Marion Labovitz, Robert Klonskey, 249 F.2d 619, 3rd Cir. (1957)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Joseph Kuzma, Joseph Roberts, Benjamin Weiss, David Davis, Thomas Nabried, Irvin Katz, Walter Lowenfels, Sherman Marion Labovitz, Robert Klonskey, 249 F.2d 619, 3rd Cir. (1957)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Thomas Lavelle, 306 F.2d 216, 2d Cir. (1962)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Thomas Lavelle, 306 F.2d 216, 2d Cir. (1962)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Shasta Minerals & Chemical Company v. Securities and Exchange Commission, 328 F.2d 285, 10th Cir. (1964)Document5 pagesShasta Minerals & Chemical Company v. Securities and Exchange Commission, 328 F.2d 285, 10th Cir. (1964)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Storey, 10th Cir. (2014)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Storey, 10th Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Joel Rosenberg, 257 F.2d 760, 3rd Cir. (1958)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Joel Rosenberg, 257 F.2d 760, 3rd Cir. (1958)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- ILLINOIS CENTRAL RAILROAD COMPANY v. Edwards, 203 U.S. 531 (1906)Document5 pagesILLINOIS CENTRAL RAILROAD COMPANY v. Edwards, 203 U.S. 531 (1906)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Ex Rel. Alton Cannon v. Harold J. Smith, Superintendent, Attica Correctional Facility, Attica, New York, 527 F.2d 702, 2d Cir. (1975)Document10 pagesUnited States Ex Rel. Alton Cannon v. Harold J. Smith, Superintendent, Attica Correctional Facility, Attica, New York, 527 F.2d 702, 2d Cir. (1975)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Frazier v. United StatesDocument17 pagesFrazier v. United StatesScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Communist Party of United States v. Subversive Activities Control BD., 351 U.S. 115 (1956)Document11 pagesCommunist Party of United States v. Subversive Activities Control BD., 351 U.S. 115 (1956)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Anthony Joseph Russo, Jr. v. William Matthew Byrne, JR., 409 U.S. 1219 (1972)Document3 pagesAnthony Joseph Russo, Jr. v. William Matthew Byrne, JR., 409 U.S. 1219 (1972)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Michael, 180 F.2d 55, 3rd Cir. (1950)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Michael, 180 F.2d 55, 3rd Cir. (1950)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- George H. Outing, Jr. v. State of North Carolina, 344 F.2d 105, 4th Cir. (1965)Document3 pagesGeorge H. Outing, Jr. v. State of North Carolina, 344 F.2d 105, 4th Cir. (1965)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Leon Jackson, SR., 861 F.2d 266, 4th Cir. (1988)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Leon Jackson, SR., 861 F.2d 266, 4th Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Ronald H. Glantz and Anthony J. Bucci, 810 F.2d 316, 1st Cir. (1987)Document13 pagesUnited States v. Ronald H. Glantz and Anthony J. Bucci, 810 F.2d 316, 1st Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Danny 355Document5 pagesDanny 355keith in RIPas encore d'évaluation

- 02 02 35 State North Dakota On Relation P o Sathre3629Document12 pages02 02 35 State North Dakota On Relation P o Sathre3629PixelPatriotPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. NeffDocument23 pagesUnited States v. NeffScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Ernesto Fernandez, 780 F.2d 1573, 11th Cir. (1986)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Ernesto Fernandez, 780 F.2d 1573, 11th Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Clarke D. Johnson, 565 F.2d 179, 1st Cir. (1977)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Clarke D. Johnson, 565 F.2d 179, 1st Cir. (1977)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Dubuque & Pacific R. Co. v. Litchfield, 64 U.S. 66 (1860)Document20 pagesDubuque & Pacific R. Co. v. Litchfield, 64 U.S. 66 (1860)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- People v. Domingo, G.R. No. 204895, March 21, 2018Document42 pagesPeople v. Domingo, G.R. No. 204895, March 21, 2018HannahLaneGarciaPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument21 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Connie George Holmes and Joe Bedami v. United States, 284 F.2d 716, 4th Cir. (1960)Document6 pagesConnie George Holmes and Joe Bedami v. United States, 284 F.2d 716, 4th Cir. (1960)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- In Re: US V., 441 F.3d 44, 1st Cir. (2006)Document30 pagesIn Re: US V., 441 F.3d 44, 1st Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- KingCast Reply Memo To Unseal Cody Eller/Eugene Stahl Laurie List Info in Motorcycle Road Rage Case.Document6 pagesKingCast Reply Memo To Unseal Cody Eller/Eugene Stahl Laurie List Info in Motorcycle Road Rage Case.Christopher KingPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals Second Circuit.: No. 311, Docket 33019Document10 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Second Circuit.: No. 311, Docket 33019Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Uphaus v. Wyman, 364 U.S. 388 (1960)Document16 pagesUphaus v. Wyman, 364 U.S. 388 (1960)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Proposed Areas To Be InvestigatedDocument31 pagesProposed Areas To Be InvestigatedStitch UpPas encore d'évaluation

- Judge Goethals Ruling - August 2014Document12 pagesJudge Goethals Ruling - August 2014Lisa BartleyPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. (Under Seal), in Re Antitrust Grand Jury Investigation, 714 F.2d 347, 4th Cir. (1983)Document7 pagesUnited States v. (Under Seal), in Re Antitrust Grand Jury Investigation, 714 F.2d 347, 4th Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- 08 1394reissueDocument113 pages08 1394reissuepgohierPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Smith, 569 F.3d 1209, 10th Cir. (2009)Document12 pagesUnited States v. Smith, 569 F.3d 1209, 10th Cir. (2009)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Joseph L. Belculfine, 527 F.2d 941, 1st Cir. (1975)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Joseph L. Belculfine, 527 F.2d 941, 1st Cir. (1975)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Frank Grace and Ross M. Grace v. Fred Butterworth, Superintendent, Massachusetts Correctional Institution, Walpole, 586 F.2d 878, 1st Cir. (1978)Document4 pagesFrank Grace and Ross M. Grace v. Fred Butterworth, Superintendent, Massachusetts Correctional Institution, Walpole, 586 F.2d 878, 1st Cir. (1978)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals First CircuitDocument6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals First CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Judge H. Lee Sarokin - Speaks Out On Wrongful Convictions of IRP6 in ColoradoDocument7 pagesJudge H. Lee Sarokin - Speaks Out On Wrongful Convictions of IRP6 in ColoradoOlivia HodgesPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Green, 435 F.3d 1265, 10th Cir. (2006)Document13 pagesUnited States v. Green, 435 F.3d 1265, 10th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Charles E. Steele, 241 F.3d 302, 3rd Cir. (2001)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Charles E. Steele, 241 F.3d 302, 3rd Cir. (2001)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- In Re Impounded, 178 F.3d 150, 3rd Cir. (1999)Document14 pagesIn Re Impounded, 178 F.3d 150, 3rd Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Cases 226 294Document119 pagesCases 226 294Christina AurePas encore d'évaluation

- Frank Delano Gay, Oliver Townsend and Willie Olen Scott v. Marcell Graham, Warden, Utah State Prison, 269 F.2d 482, 10th Cir. (1959)Document6 pagesFrank Delano Gay, Oliver Townsend and Willie Olen Scott v. Marcell Graham, Warden, Utah State Prison, 269 F.2d 482, 10th Cir. (1959)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Rasmieh Odeh Prosecution - Order On Motion To Empanel Anonymous JuryDocument10 pagesRasmieh Odeh Prosecution - Order On Motion To Empanel Anonymous JuryLegal InsurrectionPas encore d'évaluation

- Whitney v. Florida, 389 U.S. 138 (1967)Document4 pagesWhitney v. Florida, 389 U.S. 138 (1967)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Gene Stipe and Red Ivy, 653 F.2d 446, 10th Cir. (1981)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Gene Stipe and Red Ivy, 653 F.2d 446, 10th Cir. (1981)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Dianne Sutherland, United States of America v. Alan W. Fini, 929 F.2d 765, 1st Cir. (1991)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Dianne Sutherland, United States of America v. Alan W. Fini, 929 F.2d 765, 1st Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Flores v. PeopleDocument6 pagesFlores v. PeopleJeamie SalvatierraPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Nunez, 146 F.3d 36, 1st Cir. (1998)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Nunez, 146 F.3d 36, 1st Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Petitioners vs. vs. Respondent Arturo Zialcita Zosimo Rivas Solicitor General Antonio P. Barredo Solicitor Vicente A. TorresDocument5 pagesPetitioners vs. vs. Respondent Arturo Zialcita Zosimo Rivas Solicitor General Antonio P. Barredo Solicitor Vicente A. TorresOdette JumaoasPas encore d'évaluation

- Motion New Trial WWH 08-08-11Document50 pagesMotion New Trial WWH 08-08-11William N. Grigg100% (1)

- G.R NO. 229781 - de Lima vs. GuerreroDocument5 pagesG.R NO. 229781 - de Lima vs. GuerreroJeacellPas encore d'évaluation

- Fed. Sec. L. Rep. P 95,346 Securities and Exchange Commission, Applicant-Appellee v. Robert Howatt, 525 F.2d 226, 1st Cir. (1975)Document6 pagesFed. Sec. L. Rep. P 95,346 Securities and Exchange Commission, Applicant-Appellee v. Robert Howatt, 525 F.2d 226, 1st Cir. (1975)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- James W. Lewis v. United States of America, James G. Burley v. United States, 277 F.2d 378, 10th Cir. (1960)Document4 pagesJames W. Lewis v. United States of America, James G. Burley v. United States, 277 F.2d 378, 10th Cir. (1960)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Dolan Wells, 995 F.2d 189, 11th Cir. (1993)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Dolan Wells, 995 F.2d 189, 11th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Greene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesGreene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Payn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Document8 pagesPayn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs50% (2)

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Wilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesWilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Brown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Document6 pagesBrown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Webb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document18 pagesWebb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Northglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- People Vs PepitoDocument8 pagesPeople Vs PepitoDPPas encore d'évaluation

- Legal Med Case DigestsDocument29 pagesLegal Med Case DigestsAnthony ElmaPas encore d'évaluation

- In Re Asoy - Res Ipsa LoquiturDocument2 pagesIn Re Asoy - Res Ipsa LoquiturMaria Louissa Pantua AysonPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Fire HandoutsDocument4 pagesIntroduction To Fire HandoutsBfp Atimonan QuezonPas encore d'évaluation

- People vs. SabioDocument12 pagesPeople vs. SabioDexter Gascon0% (1)

- Matt Dunn Memo Re Chris ReaDocument5 pagesMatt Dunn Memo Re Chris ReaDaily FreemanPas encore d'évaluation

- Petition For Correction of Entry Birth CertificationDocument5 pagesPetition For Correction of Entry Birth CertificationFlorentine T. Garay100% (4)

- People Vs Villena - 140066 - October 14, 2002 - Per Curiam - en BancDocument10 pagesPeople Vs Villena - 140066 - October 14, 2002 - Per Curiam - en BancSamantha De GuzmanPas encore d'évaluation

- ALIAS KINO LASCANO (At Large) and ALFREDO DELABAJAN Alias TABOYBOY, AccusedDocument5 pagesALIAS KINO LASCANO (At Large) and ALFREDO DELABAJAN Alias TABOYBOY, AccusedVanzPas encore d'évaluation

- ComplaintDocument2 pagesComplaintBaesittieeleanor MamualasPas encore d'évaluation

- UNITED STATES v. WILLIAM SOTO-BENÍQUEZ, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. JUAN SOTO-RAMÍREZ, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. EDUARDO ALICEA-TORRES, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. RAMON FERNÁNDEZ-MALAVÉ, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. CARMELO VEGA-PACHECO, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. ARMANDO GARCÍA-GARCÍA, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. JOSE LUIS DE LEÓN MAYSONET, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. RENE GONZALEZ-AYALA, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. JUAN ENRIQUE CINTRÓN-CARABALLO, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. MIGUEL VEGA-COLÓN, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. MIGUEL VEGA-COSME, 356 F.3d 1, 1st Cir. (2004)Document58 pagesUNITED STATES v. WILLIAM SOTO-BENÍQUEZ, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. JUAN SOTO-RAMÍREZ, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. EDUARDO ALICEA-TORRES, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. RAMON FERNÁNDEZ-MALAVÉ, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. CARMELO VEGA-PACHECO, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. ARMANDO GARCÍA-GARCÍA, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. JOSE LUIS DE LEÓN MAYSONET, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. RENE GONZALEZ-AYALA, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. JUAN ENRIQUE CINTRÓN-CARABALLO, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. MIGUEL VEGA-COLÓN, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. MIGUEL VEGA-COSME, 356 F.3d 1, 1st Cir. (2004)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

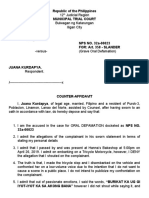

- Judicial Counter Affidavit - Juana KurdapyaDocument3 pagesJudicial Counter Affidavit - Juana KurdapyaAlthea QuijanoPas encore d'évaluation

- People V Dio PDFDocument5 pagesPeople V Dio PDFLeona SanchezPas encore d'évaluation

- Leading Question: Objections To QuestionsDocument10 pagesLeading Question: Objections To QuestionsFatima Sotiangco100% (3)

- Comments On MCPS Proposal - Ellen MugmonDocument48 pagesComments On MCPS Proposal - Ellen MugmonParents' Coalition of Montgomery County, MarylandPas encore d'évaluation

- Republic of The Philippines Department of Justice Office of The Prosecutor ManilaDocument2 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Department of Justice Office of The Prosecutor ManilaEmmagine E EyanaPas encore d'évaluation

- People Vs Tolentino DigestDocument1 pagePeople Vs Tolentino DigestPauline Vistan Garcia100% (1)

- Mrs. Calanoc Complaint For EasementDocument2 pagesMrs. Calanoc Complaint For EasementPatrio Jr SeñeresPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Paniagua-Ramos, 1st Cir. (1998)Document47 pagesUnited States v. Paniagua-Ramos, 1st Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Julian Gil, 11th Cir. (2014)Document21 pagesUnited States v. Julian Gil, 11th Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- People Vs MaderaDocument8 pagesPeople Vs Maderavince005Pas encore d'évaluation

- 126 Rules of Court - Criminal Proceedure PDFDocument2 pages126 Rules of Court - Criminal Proceedure PDFHoney EscovillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study - TutorialDocument3 pagesCase Study - TutorialHusni Muhamad RifqiPas encore d'évaluation

- People V CA GR No. 126379Document11 pagesPeople V CA GR No. 126379Kliehm NietzschePas encore d'évaluation

- PublishedDocument29 pagesPublishedScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- REDACTED Oracle Defendants' Motion For Sanctions Relating To The David Jurk CID Transcript Including Scheduling ReliefDocument47 pagesREDACTED Oracle Defendants' Motion For Sanctions Relating To The David Jurk CID Transcript Including Scheduling ReliefElizabeth HayesPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Moreno Straccialini, 4th Cir. (2012)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Moreno Straccialini, 4th Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Art. III, Section 12 Case Digests & Bar QuestionsDocument6 pagesArt. III, Section 12 Case Digests & Bar Questionsfraimculminas100% (2)

- 11 Judicial RegionDocument9 pages11 Judicial RegionNovo FarmsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Miguel Gonzalez Vargas, 558 F.2d 631, 1st Cir. (1977)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Miguel Gonzalez Vargas, 558 F.2d 631, 1st Cir. (1977)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- The Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismD'EverandThe Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (8)

- Summary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesD'EverandSummary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1635)

- Power Moves: Ignite Your Confidence and Become a ForceD'EverandPower Moves: Ignite Your Confidence and Become a ForcePas encore d'évaluation

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityD'EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (28)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionD'EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (404)

- Summary of Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James ClearD'EverandSummary of Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James ClearÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (560)

- The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: The Infographics EditionD'EverandThe 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: The Infographics EditionÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (2475)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedD'EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (81)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDD'EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Maktub: An Inspirational Companion to The AlchemistD'EverandMaktub: An Inspirational Companion to The AlchemistÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (3)

- The Mountain is You: Transforming Self-Sabotage Into Self-MasteryD'EverandThe Mountain is You: Transforming Self-Sabotage Into Self-MasteryÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (882)

- Summary of Dan Martell's Buy Back Your TimeD'EverandSummary of Dan Martell's Buy Back Your TimeÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems ModelD'EverandNo Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems ModelÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (4)

- Breaking the Habit of Being YourselfD'EverandBreaking the Habit of Being YourselfÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (1458)

- The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentD'EverandThe Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (4125)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeD'EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeÉvaluation : 2 sur 5 étoiles2/5 (1)

- Briefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndD'EverandBriefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndPas encore d'évaluation

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsD'EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsPas encore d'évaluation

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsD'EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Summary of The 48 Laws of Power: by Robert GreeneD'EverandSummary of The 48 Laws of Power: by Robert GreeneÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (233)

- Summary of The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental IllnessD'EverandSummary of The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental IllnessPas encore d'évaluation

- Weapons of Mass Instruction: A Schoolteacher's Journey Through the Dark World of Compulsory SchoolingD'EverandWeapons of Mass Instruction: A Schoolteacher's Journey Through the Dark World of Compulsory SchoolingÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (149)