Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Factionandenclaves PDF

Transféré par

norhaya09Description originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Factionandenclaves PDF

Transféré par

norhaya09Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

ARTICLE

10.1177/0047287504265501

AUGUST

JOURNAL

2004

OF TRAVEL RESEARCH

Factions and Enclaves: Small Towns and

Socially Unsustainable Tourism Development

JEFFREY SASHA DAVIS AND DUARTE B. MORAIS

Pressured by the decline of extractive industries and agriculture, many small towns are trying to acquire a share of

the tourism industry. While some communities decide to develop tourism from within their towns, often rural places turn

to large-scale privately owned tourism enterprises to act as

engines of economic development. While many studies have

examined how tourism can have negative social impacts in

rural communities, few studies detail how rural communities attitudes toward tourism can suffer when locals feel

alienated from planning/development decisions. In this

study, the authors examined data from participant observation and semistructured interviews in Williams, Arizona, to

determine whether changes in community attitudes toward

tourism followed patterns suggested by the established theoretical models of social carrying capacity and community

adaptation to a social disruption. We found that Williams is a

case where the fast pace of tourism development causes

community attitudes toward tourism to decline over time.

Keywords: rural tourism; community attitudes; sustainable development; Arizona; Grand

Canyon

Tourism is considered an important tool for economic

development in rural America, and many small towns are

trying to acquire a share of this growing industry (Galston

and Baehler 1995). Rural areas look to tourism as a means of

community development and economic diversification.

While some community leaders in small towns may often

focus on the positive aspects of tourism development, many

authors stress that both positive and negative consequences

are involved with increased tourism activity and dependence

(Allen et al. 1993; Lankford 1994; Long and Nuckolls 1992;

Long, Perdue, and Allen 1990; Matsuoka 1991; Rothman

1998).

Many approaches can be taken by small towns to develop

their tourist industries. Frequently, towns seek to increase

visitation by developing existing heritage resources. This is

exemplified by the many towns that have taken advantage of

the National Main Street Program to restore historic buildings in aging downtowns (Francaviglia 1996; Skelcher

1991). The impetus for this kind of tourism development

often comes from within the community. Conversely, a town

may choose to develop tourism in partnership with an outside company. Ski resorts, theme parks, casinos, golf resorts,

and tourist railroads all fall into the category of corporateowned attractions located in and around rural towns. In this

article, we will examine the impact of this kind of tourism

development on rural towns. These corporate tourism

enterprises differ from locally created ones in important

ways. First, they often have more capital resources than can

be marshaled by community groups. Second, the decisionmaking process regarding the development may not be easily

influenced by people in the community (Rothman 1998).

Most of the important decisions may be made at an office

that may be located in a distant metropolitan area. This can

seriously compromise tourism development strategies that

are based on community involvement.

For some observers, tourism in rural areas is seen as a

clean industry that can help towns recover from economic

depression. Some authors have stressed, however, that the

economic development aspects of tourism in rural areas

needs to be balanced against the social and environmental

impacts that can also arise (Holden 2000; Long and Lane

2000). Still other studies have shown that attitudes toward

rural tourism development differ depending on whether the

people are business owners, planners, politicians, developers, workers, residents, or members of certain ethnic groups

(Allen et al. 1993; King, Pizam, and Milman 1993; Lankford

1994; Lew 1989; Matsuoka 1991; Pearce 1994).

A particular focus of tourism researchers has been measuring attitudes toward tourism based on the level of tourism

activity in the town. Two general theories have developed

concerning community acceptance of tourism development

in rural towns. The first centers on Butlers (1980) idea of the

resort cycle. This perspective posits that tourism development starts off slowly in a community and builds through

time. The quality of life in the community is said to decrease

as tourism development increases past the communitys tolerance level. Others have shown how community members

acceptance of tourism activity drops sharply when the negative consequences of tourism development (crime, parking

problems, traffic, loss of a local sense of place) engulf a

community overwhelmed with tourists. Like biological systems, communities are said to have a social carrying capacity for tourist activities above which irritation occurs

(Doxey 1976; Long, Perdue, and Allen 1990).

The second theory is concerned with the effects of

boomtown tourism (Perdue, Long, and Kang 1999). This

Jeffrey Sasha Davis is an assistant professor in the Department

of Geography at the University of Vermont in Burlington. Duarte B.

Morais is an assistant professor in the School of Hotel, Restaurant,

and Recreation Management, Pennsylvania State University in

University Park.

Journal of Travel Research, Vol. 43, August 2004, 3-10

DOI: 10.1177/0047287504265501

2004 Sage Publications

AUGUST 2004

perspective is concerned with large tourism developments,

such as casinos, coming rather suddenly into rural communities. This theory posits that community acceptance of tourism activity starts off low because of the initial social disruption caused by the appearance of a large-scale tourism

operation. Therefore, as opposed to models based on Butlers (1980) development cycle, the community adapts to the

tourism operations existence, and through time, residents

attitudes toward tourism become more positive. This social

disruption perspective assumes that after the establishment

of the large tourism operation that the surrounding

community is able to adapt.

These two theories are not necessarily antithetical as

much as they are applicable under different tourism development situations. The case study of Williams, Arizona, and

the Grand Canyon Railway described in this article represents yet another scenario of tourism development. In Williams, neither the model of social carrying capacity nor the

model of community adaptation to a social disruption

applies. As we will describe in more detail, Williams is the

site of a boomtown-style tourism development where in a

very short period of time a large corporate tourism operation

transformed the town. Unlike the casino communities examined by Perdue, Long, and Kang (1999), however, Williams

has not been able to adapt to the situation, and community

attitudes toward tourism have sharply decreased through

time. This is due to the fact that the community in Williams

has not been able to adapt to the tourism development

because it has been a growing, rather than static, operation.

We argue that the rate at which the large tourism enterprise

has expanded has exceeded the threshold of what could be

considered socially sustainable development.

Efforts by people in the town of Williams to adapt to the

growth of the tourism operation and share in the economic

benefits of the tourists visiting the town have been largely

unsuccessful. While it is important not to conflate residents

acceptance of tourism with a towns ability (or inability) to

tap into the streams of tourist revenue, the case of Williams

shows that the perceived lack of benefits to the town from

tourism has produced a tremendous amount of animosity

toward the tourism enterprise. There are two primary reasons

why the town has been unable to adapt to the growth of the

tourism operation. First, the expanding tourism company has

managed to form an enclave that restricts tourist interaction

between its property and the town. Second, the rivalry

between factions in the community has hindered the ability

of townspeople to successfully undertake projects that would

enable the town to adapt to the growing tourism operation. In

this article, we will detail the ways in which both of these

processes can cause towns to fail to adapt to, and benefit

from, large-scale tourism development.

BACKGROUND: WILLIAMS, ARIZONA, AND

THE GRAND CANYON RAILWAY

Williams, Arizona (population 2,529), is a typical small

town that over the past hundred years has experienced the

rise and fall of resource extraction industries such as logging,

ranching, and mining as well as the ebbs and flows of the

tourist trade (City of Williams 1998; Fuchs 1953; Richmond

1995). As of 1989, Williams has been host to the Grand Canyon Railway. This tourist railroad serves as a prime example

of a tourism enterprise situated in a rural host community.

Over the past decade, the town has seen the gala of the Railways inauguration in 1989, the growth of its popularity, the

removal of its business offices from town, and the Railways

expansion of its depot into a full resort destination.

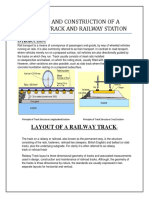

Williams is situated along Interstate 40 in northern Arizonas Coconino County (see Figure 1). Flagstaff is Williamss nearest neighbor and historically its biggest rival in

the tourist trade. As a city of 50,000 people, Flagstaff has

often overshadowed Williams. The closest large metropolitan area to Williams is Phoenix, Arizona, 170 miles by interstate freeway to the south. Williamss climate and vegetation

are integral parts of its appeal to tourists. Williamss elevation of 6,770 feet is responsible for the towns cool climate.

Snow is frequent in the winter, and high temperatures on

summer days rarely reach 32 degrees Celsius (90 degrees

Fahrenheit). Tall Ponderosa pines circle Williams as part of

the Kaibab National Forest. In the summer, the main tourist

season in Williams, many of Williamss weekend tourists are

escapees from Phoenixs scorching temperatures. It is not

uncommon for temperatures in Phoenix to be 15 degrees

Celsius (26 degrees Fahrenheit) higher than those in

Williams.

The downtown of Williams is laid out on a grid aligned

with the railroad tracks of the Burlington Northern-Santa Fe

(see Figure 1). While most of the trains on the line run on

tracks that bypass the center of Williams, some trains bound

for southern destinations still rumble through downtown.

Route 66 parallels the tracks one block to the south. As a consequence of both the railroad and Route 66, the commercial

area of downtown Williams is stretched linearly. Businesses

line Route 66 through the entire town. More recently, development has moved out toward the freeway interchanges.

As the historically important resource extraction industries have waned in recent decades, Williams has become

ever more dependent on tourism. Currently, 53% of the

workforce is employed serving tourists, and it is estimated

that an average of 15,000 vehicles go through Williams each

day (Arizona Department of Commerce 1998). Williamss

registered trademark of Gateway to the Grand Canyon

exemplifies the areas emphasis on tourism. In particular, the

slogan shows the reliance of Williams on tourists bound for

somewhere else. While Williams is starting to promote itself

as a tourist destination with its own ski resort, golf course,

fishing lakes, and forest trails, it is still primarily a gateway

community (City of Williams 1998). Williamss proactive

attitude to promotion dates back to the beginning of the century when, in 1907, a Board of Trade was established to promote the town as a health destination and to dispel the towns

image of being lethargic (Fuchs 1953). Located 60 miles

south of the Grand Canyon, however, it has always been

overshadowed as a tourist attraction in itself by the nearby

national park.

In the past 50 years, one of the most crippling blows to

the towns economy was the bypass of Route 66, which runs

through the downtown by Interstate 40. The bypass did not

occur until 1984 (the town was the last section of Route 66 to

be bypassed in the United States and has the last street light

between Los Angeles and Chicago in a local museum). The

mere announcement of the bypass in 1957, however, was the

real trigger for economic depression in Williams. A longtime

resident and businessperson claimed that the town was redlined after the announcement. Banks refused to lend for

JOURNAL OF TRAVEL RESEARCH 5

FIGURE 1

MAP OF WILLIAMS, ARIZONA

building in the town, even to a McDonalds restaurant that

intended to build at an interstate freeway interchange. Many

of the people interviewed in Williams stated that in the late

1980s, the town was dying. Statistically, Williamss population and tax income were holding steady in the late 1980s.

Whether the town was dying can be debated, but it certainly

appeared to be stagnating.

The Grand Canyon Railway stepped into this situation in

1989. The company, owned by wealthy Arizonan Max

Biegert, bought the right-of-way, tracks, and depots of the

defunct railway line that had run from Williams to the Grand

Canyon. The railroad was originally built in 1901 as a spur to

the east-west trunk line of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa

Fe Railway. The railway was used to ferry tourists north to

the Grand Canyon from the junction at Williams. It also took

cattle, timber, and ore from the area south of the Grand Canyon to the trunk line of railroad. As the harvestable timber

decreased, the ore was mined out, and the completion of a

highway from Williams to the Grand Canyon became the

major artery of tourist traffic, the railroad ceased operation in

the early 1970s.

In 1989, the Grand Canyon Railway first bought the resources of the old railroad to scrap the tracks and salvage the

metal. Soon, Max Biegert was convinced by Williamss merchants and town government to turn the railway into a tourism attraction. The idea of resurrecting the railway as a tourist railroad had been discussed by many in Williams as a

vehicle for economic development since the early 1980s.

When Max Biegert decided to go forward with turning the

railway into a tourist attraction, the pace of development was

swift, and the local newspaper was singing the praises of a

town saved. When the railroad was ready to be reborn,

phrases like the ones below appeared in the September 14,

1989, issue of the Williams News:

Laying a straight track to economic prosperity.

We can now see the economic light at the end of the

tunnel.

Cant you hear the whistle blowing? Prosperity here

we come!

Making tracks to the yesteryear of tomorrow.

No more chug, chug, chug, its full steam ahead for

Williams. (Rees 1989)

In January 1989, the Grand Canyon Railway announced

its intentions of beginning operation in September of that

same year. In those 9 months, the railway managed to renovate the abandoned depots at both ends of the line; fix the

tracks, bridges, and rail bed along the 60-mile route; rebuild

an antiquated steam engine and 1920s-era Pullman cars; and

build a facility for the engine and cars. The speed of development was incredible, and the amount of resources poured in

to Williams in those 9 months surpassed even the dreams of

the towns business people. The company spent more money

in Williams in 1989 than the net worth of the town that year.

The opening of the Grand Canyon Railway was seen by

many as a sign of Williamss economic salvation. Banks

started lending for development, and most of the downtown

property changed hands. In the next 10 years, more touristoriented shops opened downtown, and 19 new hotels were

opened. The town governments general fund rose from $1.5

million in 1989 to $3.4 million in 1999. Property owners

benefited as the assessed value of property in Williams doubled in the year following the railways start of business.

Another indicator of growth is that the Bed, Board and Booze

(BBB) tax revenues increased from $45,000 to $280,000

from 1991 to 1998.

There has also been an increase in the number of businesses operating in Williams. Over the entire time period from

1987 to 1998, the number of businesses in Williams increased

by 48. This is an impressive number given the gloomy forecasts that were made when the interstate bypass of the town

was announced in 1957. There were large increases in the

number of hotels, restaurants, craft shops, and other businesses. While some of this increase was due to new businesses

downtown, a large number of the new businesses were located

at the new freeway interchanges. The most dramatic change in

new business development was the addition of 19 new hotels

in the community after the railway opened.

The railway has also done well in the first 10 years of its

operation. It has been drawing 150,000 tourists a year to Williams and has negotiated an Amtrak stop in Williams for a

rails-to-rails package. The railway has also started its own

air service, Farwest Airlines, to fly passengers from Phoenix,

Arizona, and Southern California to take the train. This

effectively has made the Grand Canyon a possible day-trip

from those regions. Furthermore, the railway-owned Fray

Marcus Hotel adjacent to the train depot has been expanded

to accommodate more tourists.

While all of this sounds like a success story of tourism

development, there have been some important negative consequences. First, not everybody in the community has been

impacted positively by the railways operation. The property

speculation and development has driven up rents, while

wages hover around the minimum wage. None of the wage

earners we spoke with indicated they were better off in 1999

than in 1989. Most workers indicated the low wages of tourism jobs coupled with high rents and food costs (not to

AUGUST 2004

mention a 3% sales tax on food in the town) made living in

Williams extremely difficult. Merchants in the downtown

area have experienced some increased tourist spending, but

that has been offset by increased rent. One problem for merchants is that while the railway brings around 150,000 tourists per year, the tourists are on the train or at the Grand Canyon the majority of the day. The tourists are only at the depot

between 8:00 and 9:30 a.m. and then after the train returns at

5:30 p.m. It is a long day on the train and walking around

Grand Canyon Village. The window of opportunity for

capturing a tourists dollars in Williams is short.

In 1989, the railway had forecasted 800 new jobs in Williams within 10 years. The merchants and newspaper were

predicting thousands of tourists dropping millions of dollars

into local businesses (Williams News 1989). Neither of these

things, however, has come to pass. The railway does supply

approximately 200 jobs directly in Williams, less during the

winter. What is lacking is the predicted creation of jobs in the

community due to the spending of tourists in the town. Many

merchants claim the tourists taking the train do not come

downtown. This seems odd given that the Grand Canyon

Railways Williams Depot is 100 meters from downtown.

Many people in the community expressed animosity toward the railroad during our interviews in Williams. Many

residents claimed that the Grand Canyon Railway was monopolizing tourist spending. It was claimed that the railway was actively creating a tourism enclave that restricted

interaction between itself and the downtown shops. While

respondents generally felt that the Grand Canyon Railway was entitled to keep much of the spending tourists

brought in, they also felt that more interaction between the

railroad and town was desirable. One merchant downtown

reported,

They do take a major portion of our business away

from us. But you really cannot blame them, because

they are in business to make money. Whatever they

are doing they are doing it right. So they are getting

the tourists. They are making the money. It is just that

they are not willing to share it by sending people out

by saying, Two blocks away is a wonderful little

town. Go shop in the shops. They are not going to do

that because they want all of the money over there.

But that is business, you know. I dont like it, but you

cannot blame them.

METHOD

First, we collected quantitative data from the town government on the economic impacts of the tourist resort. Then

an inventory was done to determine the numbers and locations of businesses that opened and closed from 1999 to

2000. We also examined all issues of the local newspaper,

Williams News, dating back to 1988the year prior to the

announcement of the Grand Canyon Railway. We also had

an opportunity to ride the train to the Grand Canyon to get an

understanding of the experience.

Another part of the study entailed participant observation. This method was used to record the movement of tourists in and around the depot to determine what the tourists

were doing and where they were going before they boarded

the train. Observations were done on a Monday, Wednesday,

Friday, Saturday, and Sunday during the summer (peak tourism season). Since the railway station and its parking lot lay

opposite a group of railroad tracks from downtown, we

observed how many pedestrians crossed the tracks in the

hour and a half prior to the trains departure from Williams

(8:00 to 9:30 a.m.) and the hour following its return (5:30 to

6:30 p.m.). This was compared against the total numbers of

passengers on the train that day. The ticket count was

obtained from the company for each day of observation.

On a different Monday, Wednesday, Friday, Saturday,

and Sunday, we counted the number of people at specific

locations at the station every 15 minutes during the hour and

a half prior to the departure of the train (8:00 to 9:30 a.m.).

Observations were made at different locations around the

station: the ticket windows, the gift shop, the Wild West

Show, the museum, the restaurant, the front of the depot, the

platform, and the front of the train. To control for variations

in the total number of people at the station each day, the

count of people at the specific locations was divided by the

total ticket count for the day. The object of this piece of the

research project was to map the flow of tourists around the

station through time.

We also performed semistructured interviews to gauge

community attitudes toward the tourism resort as well as to

ascertain what the community has done to try to take more

advantage of the tourism development in Williams. Respondents were selected based on their availability to contribute

to the questions posed by this study. We strove to find what

Creswell (1998, 119) referred to as information-rich cases

that manifest the phenomenon intensely. Sampling of this

kind is used in qualitative research to find cases most illustrative of the research topic. Long, in-depth interviews were

conducted with 22 people. The interviewees were Grand

Canyon Railway officials, merchants in downtown Williams, wage earners working in Williams (both for the railway and for other tourism-oriented businesses), and local

government officials. Interviewees were approached in person, and we either set up appointments for a later interview or

occasionally interviewed them on the spot if it was convenient for them. Some of the particularly informative interviewees were contacted again for follow-up interviews. All

the interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed. The

responses were then coded according to various research

interests (e.g., attitudes toward railway, cooperation

between city and merchants, etc.) and grouped into common themes. These various methods, used in concert, gave a

detailed description of the relationship between Williams

and the Grand Canyon Railway.

DISCUSSION

Downtown Merchants and the Railway

Most of the businesses in downtown Williams could be

labeled as tourist-oriented. While there are a few businesses that cater to local residents, the downtown is currently

dominated by small gift shops, tourist-oriented restaurants,

and motels. Most of the merchants reported that their businesses depended on tourist spending. The merchants noted

that much of their business comes in the evening from tourists traveling by car to the Grand Canyon or other destinations along Interstate 40. They are also eager to entice more

JOURNAL OF TRAVEL RESEARCH 7

of the tourists taking the Grand Canyon Railway into the

downtown area. As we noted, many people in Williams, particularly downtown merchants, felt that tourist spending was

being monopolized by the Grand Canyon Railway. Even

though the downtown is a mere 100 meters from the railroad

depot, many respondents claimed that very few tourists taking the train ventured into downtown to spend money in the

local shops.

From our observations of tourists, we found that only an

average of 4.2% (SD = 0.9%) of the ticket count for the day

visited downtown in the hour and a half before the morning

departure of the train. In the evening, an average of 7.7%

(SD = 2.6%) of railway passengers ventured downtown in

the hour after arrival. Since the average number of passengers per day during this busy time of the year was 730, on a

given day approximately 30 passengers would go downtown

in the morning and 56 at night. Informal observations during

the winter showed far less interaction. While this is certainly better than no tourists at all, it is a surprisingly small

trickle given the small distance separating the depot and

downtown.

Residents complained that the resort was becoming a

tourist enclave in the middle of town. One merchant commented that the railway depot was becoming its own city.

There are examples of tourism enclaves sealed off from surrounding communities to greater extent than Williams

(Freitag 1994; Hernandez, Cohen, and Garcia 1996). Our

observations in Williams, however, do indicate that there is

much less interaction than one would expect to find between

an attraction and its surroundings. While the close proximity

of the downtown and depot would indicate a greater interaction between them, the shape of landscapes can have a powerful effect on how people move through an area (Goss 1993;

Gottdiener 1997).

There are three principal ways that the landscape has

been manipulated to produce this effect. First, the position of

the buildings and other structures on the depot property disparages interaction with downtown Williams. For instance,

the restaurant constructed on the depot property in 2000

effectively blocks any view of downtown from the parking

area. Also, the recent rebuilding of the predeparture Wild

West Show stage on the opposite end of the depot property

from downtown serves to draw people away from access

points to downtown. Second, the services provided by the

railway aim to fulfill the desires of tourists without their

needing to leave the property. The depot has recently added

large gift shops, a 300-seat restaurant, a coffee stand, and a

small museum. Last, the railway has developed a coherent

image theme for the depot that the surrounding town has not

effectively duplicated. In other words, the depot is like a

theme park that attracts tourists seeking a certain experience

that exists only within the bounds of its property.

Company officials were quite frank with us about their

plans for the Williams Depot. They envisioned a complete

tourist destination that had everything tourists would need

without having to leave the property. A company representative described what the ideal tourist would do:

Stay in the Fray Marcus hotel [which is run by the

Railway and on the depot property]. We are adding

onto that. We are basically doubling that in size. We

have a restaurant. It seats 300 people, so thats pretty

large. Take a look at the museum. You could spend at

least an hour in the area looking at the pictures, looking at the exhibits, and reading about the history of the

Railway. There are three gift shops out there and all of

them are pretty expansive in what they have. Buy

yourself a little something to remember the trip by, a

video, or whatever. Go out and make the Wild West

show [also on the property]. That starts every morning at 9:00. Then I would, after the show, just make

sure that you get on the train in time.

This view conflicts with the desires of most merchants in the

downtown, who view the railway as an engine of economic

development for the town. This image was one that the railway itself had made considerable mention of when the company was first coming into the community. Some respondents reported that the company received many concessions

and deals from the town and that they have not helped the

community enough in return. One merchant said,

[The Railway] will continue to further divide the railroad operation visually, and accessibility wise [from

the downtown] to keep the hotel guests away from the

community. In every step theyve made, every conscious decision theyve made, is to block that off.

The key goal for operators of tourism-oriented businesses in

downtown Williams has been to get the tourists who are already in Williams into the downtown area. In particular, the

merchants were looking for ways to attract tourists from

across the tracks at the train depot. The strategies that have

been attempted fall into two general categories: attractive activities and landscape changes.

The attractive activities are few but are successful. One

business sends its employees in a 1950s-era car, with the

name of the diner prominently painted on the side, to greet

the train as it returns to Williams in the evening. A largerscale undertaking is the arrangement of a brass band leading

tourists to gunfights in the downtown streets of Williams

in the early evenings in the summer. A group of local high

school students dress in Civil Warera uniforms, greet the

trains arrival, and then in a pied piperlike manner march

into the downtown hoping to bring tourists with them to hear

them play and to watch the gunfights.

To perform the gunfights, the city closes Route 66 to traffic for about 30 minutes while a troupe of cowboy-dressed

performers shoot it out and tell jokes. It is truly a postmodern

experience. Tourists getting off a 1920s-themed train stand

in 21st-century Williams, on Route 66, in front of a blackand-white-checkered 1950s-themed diner, watching 1880sthemed cowboys perform a staged gunfight while a 1860s

Civil War band stands ready to play once it is over. It is also a

very successful event. Approximately 300 people come to

view the gunfight, and at its conclusion they can be seen diffusing into the nearby stores. While some of these tourists are

from the railway, the vast majority of them are automobile

tourists stopping in Williams for the evening before heading

to the Grand Canyon or destinations along Interstate 40. The

gunfight is arranged, and paid for, by the local chamber of

commerce in Williams.

The chamber of commerce may be successful at putting

on the gunfights, but the efforts of the chamber and other

downtown organizations in Williams are an excellent case

study of how towns can squander opportunities to take

AUGUST 2004

advantage of tourism. While some scholars have theorized

that local businesses will develop coalitions, or growth

machines, to further their economic interests (Logan and

Molotch 1987; Paradis 2000), the experience of Williams

demonstrates that the theory may not be as universal as previously thought. As others have shown, tourism development can fracture a community into groups that support or

resist tourism development (Dogan 1989; Doxey 1976). In

Williams, however, there are divisions between groups that

all support tourism. The divisions in the community are

based on schisms other than for or against tourism, but

they have a severe impact on how tourism development

occurs.

These divisions in the community can be seen clearly

during attempts to change the landscape of Williams to capture more tourism spending downtown. In particular, downtown merchants have been trying to undertake two projects.

One is to restore buildings in the downtown and theme the

town in the Old West imagery used by the railway. The other

is to develop an attractive linkage across the railroad tracks

between the downtown and depot. As for theming Williams

in an Old West style, there are conflicts within the town. In

particular, there are two competing themes in Williams. One

is the Old West theme while the other is a 1950s-era cruising Route 66 theme. The town is a mixture of restored turnof-the-century buildings and Route 66 memorabilia stores

and diners. There is great resistance in the town to match the

railways theme or to restore all the downtown buildings to a

common historical era.

The idea of fixing the crossing area into a more attractive

walkway had been discussed since the railway came to town.

Architects from the Main Street Program came into Williams

and developed plans for an attractive crossing in 1991

(Spieler 1991). It took more than 10 years, however, to actually complete the project. One merchant noted,

For city planning, and for anything else, there are

wonderful pictures drawn, weve got a ton. We have

had more money spent on studies in this town by every organization that is supposed to help a depressed

community. A lot of it is ridiculous, but most of it

based on sound, good planning sense. But you have to

have the wherewithal to be able to do that. And you

have to have the will to follow through. That is the

problem. But there really is no leadership in this community. It is a diverse community.

number of years as a rival of the chamber of commerce. The

Main Street Program has existed off and on but has been hindered by relations with other groups. The effect of all of these

groups is that they often counter each other. One merchant

reported,

Main Street could have done a lot of good, but they

did not get the cooperation from the Chamber and

they definitely did not get the cooperation from the

city. All they wanted to do was kill Main Street, and

they did. The entire Main Street board quit on the

same day and then they put new people in and they

have not cooperated with them either. And Main

Street could do wonders for this town!

This lack of cooperation among downtown business people

has effectively hindered the ability of Williams to benefit

from the flow of tourists that the Grand Canyon Railway

brings to Williams.

Local Government and the Railway

The local government of Williams has experienced many

of the same problems that the merchants have experienced.

While clearly they have had a large boost in tax income, they

have been unable to take full advantage of the tourism development. First, they have had a difficult time accommodating

many of the decisions made by the railway. Second, the city

government has been unable to develop a coherent strategy

to take advantage of tourism because it cannot form effective

coalitions with others in the community.

In some respects, the town government has been pushed

around by the new tourism development in the same way

that many merchants feel they have been. While the merchants have felt powerless to stop the enclaving of the tourism enterprise, the city has had its own problems with the operations of the railway. A city official said of the relationship

between the tourism enterprise and city government,

I am getting the impression that it has always been a

strained relationship. They are a privately owned corporation. They have a different method of running

their business; the city has a different way of running

the city. They sometimes become very impatient. . . .

It is just that we are slower. And we are slower because of the city statutes, city ordinances and things

that we are required to operate under.

In terms of why there is no leadership in the community, another merchant said,

A former employee of the city was more specific about the

relationship:

I think politics is a big part of it. As I said, perhaps

there is fear of anybody doing anything for the welfare of the community. Maybe they are afraid that

someone else is going to look good. If you are not on a

certain clique in a small town then they do not want to

give you a credit for what you do.

It was adversarial to start with. I was at the council

meetings when Max [Max Biegert, the owner of the

Railway] was saying, If we are going to invest millions of dollars in this town we do not want to be constrained by the community. We have this big project

with a lot of things to do. Dont stand in our way.

The community development guidelines, the parking

restrictions, the traffic planning, all the rest of that

stuff [was ignored]. . . . It was a nightmare to have

them show up to build the roundhouse, a huge structure. They bring in a piece of paper with a rectangle

drawn on it and railroad tracks going in and out and

saying, This is going to be our building. We want to

There have been several competing organizations

over the past decade trying to direct Williamss tourism policy. The local chamber of commerce, which is partially

funded by the city government, has been the principal organization. There have been many other groups too. A group

specifically devoted to tourism development existed for a

JOURNAL OF TRAVEL RESEARCH 9

start right now and the plans will follow. That was

the way it went. We are in a big hurry. Weve got to

get the train started by September the 17, 1989 to hit

the deadline. We want to go. And we want to do it.

And we dont want anyone to stand in our way. This

is lots of people going through a public transit situation and they really dont want anyone to tell them

what the building codes are. And they did have a couple of lawsuits on things that they refused to do. I was

eased away from the situation, Keep an eye on them,

work with them, and all the rest of the stuff. But if it

gets down to push comes to shove, back off.

These comments shed light on two aspects of the relationship between the railway and the community. The first is

the perception by some in Williams that the railway behaves

in a rather gruff and inconsiderate way toward the community. The railway is seen as a big entity in town that can throw

its weight around to avoid rules and procedures that other

businesses must follow. Second, it shows how communication between the community and railway is less than ideal.

Changes in the companys plans are only discovered by

those in the town when they appear in the landscape or are far

into the planning stages.

One surprise action by the railway had a tremendous impact on the attitudes of people in Williams. In 1995, it moved

its headquarters and reservation offices to Flagstaff less than

a year after publicly denying it had any intentions to do so

(Williams News 1994). The city government was unable to

persuade the railway to stay. Many of the respondents I

spoke with in Williams pointed to that event as causing the

souring of community attitudes toward the railway. A former

government employee said,

On the outside you go, I dont blame those guys.

Why get tied up with a handful of small-minded little

townspeople? On the other hand, they are such a big

player in town they really ought to have more interest

in the future of the community and the benefits to both

the community and the Railway instead of standing

off and moving their operations to Flagstaff. Part of

that was to spite the community.

The other problem the town government has had is a lack

of cooperation with other groups in the community. When

we asked a government official what the city has done to try

to bring tourists into the downtown, he flatly responded that

was not the citys job and that I should ask the chamber of

commerce. Downtown merchants complained that the city

was not cooperative with initiatives put forth by the chamber

of commerce and Main Street:

Every time we [Main Street] would go to them [the

town government] for a project they would not go for

it. The state [of Arizona] said that they were going to

give us funding for better lighting downtown, . . . and

put planters along the sidewalks to put trees in and

stuff. Just to beautify it... Everything was approved

and we went to the city for matching funds and they

said No, because there was too much emphasis on

downtown. What emphasis? What emphasis? Were

dying! Businesses are going out of business every

single year.

In many respects, the town government operates as a

clique within the community that has adversarial relations

with other groups. The impact of this is that efforts to take advantage of tourism in Williams have been hindered by infighting among groups.

CONCLUSIONS

The primary message that comes out of Williamss experience with tourism development is that when a large corporate tourism operation rapidly expands, it may create a tourism situation that is not socially sustainable. There is not only

a scale at which tourism development is not socially sustainable but also a rate of growth. Counter to the predictions

of both the tourism cycle model of social carrying capacity

and the model of community adaptation to a social disruption, attitudes toward tourism in Williams have become

more negative over time as the townspeoples efforts to adapt

to the Grand Canyon Railway have been thwarted by the

operations pace of expansion.

Specifically, people in Williams have been upset by their

inability to economically take advantage of the presence of

tourists. A main reason for this lies within the community

itself. While tourism studies have examined how communities are divided over the question of tourism (Allen et al.

1993; King, Pizam, and Milman 1993; Lankford 1994; Lew

1989; Matsuoka 1991; Pearce 1994), there has been little

research on how other divisions within the host community

can have serious effects on tourism development and community attitudes toward tourism. Apparently, these divisions

may have been overlooked by most tourism planners and

academics. They may not be between groups opposed to

tourism versus those in favor of it but between groups that

may all appear to support tourism. Other cultural schisms in

the town, such as old-timers versus newcomers or hard-todefine cliques of people, can have a substantial impact on

tourism development.

These divisions in the community may be hard to discover without the in-depth open-ended questioning used in

semi-structured interviews. One of the benefits of the qualitative methods used in this study, such as participant observation and in-depth interviews, is that they can uncover why

certain individuals in a community behave as they do toward

tourism development (Walle 1997). These feelings are

important because they are the basis for how people will act

and how successful a tourism project may be. In the case of

Williams, almost all of the quantitative data point to the conclusion that tourism development has been an unqualified

success. Tax revenue, the number of new businesses, visitation numbers, and property values have all greatly increased.

Despite these increases, almost everyone we spoke with in

Williams expressed a great deal of displeasure with the situation. While this could be a case of people not being appreciative of what is actually a good situation, most of the respondents genuinely believed that promises made in 1989 have

failed to materialize. It is important to document and understand the negative attitudes of people in the community,

whether observers view them as warranted or not, because

they can impact future tourism development initiatives in the

town and surrounding region.

10

AUGUST 2004

While much of the blame for Williamss problems with

tourism development lies with the communitys inability to

cooperate with each other, the railways policy of rapid

expansion has been instrumental in souring townspeoples

attitudes toward tourism. The speed of the railways development has allowed them to build on their property much

faster than the town has been able to respond. This has led to

the construction of an enclave that restricts tourist spending

to their domain.

A lesson that Williams can deliver to other communities

considering a large-scale tourism development is that it

would be wise for people in rural towns to be critical of early

boosterist claims of economic development. Furthermore,

people in small communities need to recognize what options

they may have after inviting a big boy private tourism

development into their town. As Britton (1991) has demonstrated, it is important to recognize that tourism enterprises

are not in the business of community development, they are

in the business of accumulating capital for themselves. People in rural towns need to recognize that a company may not

care how that pursuit of profits impacts the surrounding community. Particularly, following Williamss example, rural

communities, and the researchers that study them, need to

consider how tourist spending may be confined to the

companys domain through the creation of a tourism

enclave.

As for companies setting up tourism operations in rural

areas, they should also take note of Williamss situation. As

Andereck and Vogt (2000) have demonstrated in their study

of tourism in Arizona towns (including Williams) there is a

relationship between community attitudes toward tourism

and support for continued development.1 It is in the best

interests of tourism operations not to expand too rapidly and

cross the threshold into socially unsustainable tourism. If

they do, they risk encountering community resistance caused

by negative attitudes toward tourism.

NOTE

1. Andereck and Vogt (2000, p. 31) showed that residents in

Williams were particularly negative about supporting further hotel

development. They noted this is because of the glut of hotel rooms

in the city. We found in our interviews that while some of this animosity toward the overbuilding of hotels was directed at newer hotels located near the interstate, there was particular anger by hotel

owners in the downtown area over the expansion of the railways

hotel.

REFERENCES

Allen, L., H. Hafer, P. Long, and R. Perdue (1993). Rural Residents Attitudes toward Recreation and Tourism Development. Journal of

Travel Research, 32: 27-33.

Andereck, K., and C. Vogt (2000). The Relationship between Residents attitudes toward Tourism and Tourism Development Options. Journal

of Travel Research, 39: 27-36.

Arizona Department of Commerce (1998). Community Profile: Williams.

Phoenix, AZ: Arizona Department of Commerce.

Britton, S. (1991). Tourism, Capital, and Place: Towards a Critical Geography of Tourism. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 9:

451-78.

Butler, R. (1980). The Concept of a Tourist Area Cycle of Evolution: Implications for Management or Resources. Canadian Geographer, 24: 515.

City of Williams (1998). Free Visitors Guide. Williams, AZ: Author.

Creswell, J. (1998). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing

among the Five Traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dogan, H. (1989). Forms of Adjustment: Sociocultural Impacts of Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 16: 216-36.

Doxey, G. (1976). A Causation Theory of Visitor-Resident Irritants. In

Impact of Tourism: Proceedings of the 6th Annual Conference of the

Travel Research Association. San Diego, CA: Travel Research

Association.

Francaviglia, R. (1996). Main Street Revisited: Time, Space and Image in

Small-Town America. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Freitag, T. (1994). Enclave Tourism Development: For Whom the Benefits

Roll? Annals of Tourism Research, 21: 538-54.

Fuchs, J. (1953). A History of Williams, Arizona: 1876-1951. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Galston, W., and K. Baehler (1995). Rural Development in the United

States: Connecting Theory, Practice and Possibilities. Washington,

DC: Island Press.

Goss, J. (1993). The Magic of the Mall: An Analysis of Form, Function

and Meaning in the Contemporary Retail Built Environment. Annals

of the Association of American Geographers, 83: 18-47.

Gottdiener, M. (1997). The Theming of America: Dreams, Visions, and

Commercial Spaces. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Hernandez, S., J. Cohen, and H. Garcia (1996). Residents Attitudes towards an Instant Resort Enclave. Annals of Tourism Research, 23:

775-79.

Holden, A. (2000). Environment and Tourism. New York: Routledge.

King, B., A. Pizam, and A. Milman (1993). Social Impacts of Tourism:

Host Perceptions. Annals of Tourism Research, 20: 650-65.

Lankford, S. (1994). Attitudes and Perceptions toward Tourism and Rural

Regional Development. Journal of Travel Research, 33: 35-43.

Lew, A. (1989). Authenticity and Sense of Place in the Tourism Development Experience of Older Retail Districts. Journal of Travel Research, 28: 15-22.

Logan, J., and H. Molotch (1987). Urban Fortunes: The Political Economy

of Place. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Long, P., and B. Lane (2000). Rural Tourism Development. In Trends in

Outdoor Recreation, Leisure and Tourism, ed. W. C. Gartner and D.

W. Lime. Wallingford, UK: CAB International, pp. 299-308.

Long, P., and J. Nuckolls (1992). Rural Tourism Development: Balancing

Benefits and Costs. Western Wildlands, 18, Fall: 9-13.

Long, P., R. Perdue, and L. Allen (1990). Rural Resident Tourism Perceptions and Attitudes by Community Level of Tourism. Journal of

Travel Research, 29: 3-9.

Matsuoka, J. (1991). Differential Perceptions of the Social Impacts of Tourism Development in a Rural Hawaiian Community. Social Development Issues, 13: 55-65.

Paradis, T. (2000). Conceptualizing Small Towns as Urban Places. Urban

Geography, 21: 61-82.

Pearce, P. (1994). Tourist-Resident Impacts: Examples, Explanations and

Emerging Solutions. In Global Tourism: The Next Decade, ed. W.

Theobald. Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann, pp. 103-23.

Perdue, R., P. Long, and Y. Kang (1999). Boomtown Tourism and Resident

Quality of Life: The Marketing of Gaming to Host Community Residents Journal of Business Research, 44: 165-77.

Rees, L. (1989) Ive Been Working on the RailroadNow a Reality for

Williams. Williams News, September 14, p. 5.

Richmond, A. (1995). Cowboys, Miners, Presidents, and Kings: The Story of

the Grand Canyon Railway. Flagstaff, AZ: Al Richmond.

Rothman, H. (1998). Devils Bargains: Tourism in the Twentieth-Century

American West. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

Skelcher, B. (1991). Preserving Main Street in the Heartland: The Main

Street Pilot Project in Madison, Indiana. Small Town, 22, SeptemberOctober: 4-13.

Spieler, M. (1991). Quality Design Needed to Create Towns Image of Itself. Williams News, April 18, pp. 1, 11.

Walle, A. (1997). Quantitative versus Qualitative Tourism Research. Annals of Tourism Research, 24: 524-36.

Williams News (1994). Grand Canyon Railways Offices to Remain in Williams. September 8, pp. 1, 11.

(1989). Economic Impact of the Railroad on Williams. January

12, p. 7.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Kandy Traffic ReportDocument42 pagesKandy Traffic ReportPanduka Neluwala100% (2)

- Zurich: What To Take HomeDocument72 pagesZurich: What To Take HomeAnonymous fPftQxfPas encore d'évaluation

- Factorsinfluencinghotelselection DecisionmakingprocessDocument60 pagesFactorsinfluencinghotelselection DecisionmakingprocessKhanPas encore d'évaluation

- MTK1 2018 UpsrDocument28 pagesMTK1 2018 Upsrnorhaya09Pas encore d'évaluation

- Model of Local Food ConsumptionDocument9 pagesModel of Local Food ConsumptionRomi Lycantrophe DieorlivePas encore d'évaluation

- The Influence of Food Trucks ' Service Quality On Customer Satisfaction and Its Impact Toward Customer LoyaltyDocument14 pagesThe Influence of Food Trucks ' Service Quality On Customer Satisfaction and Its Impact Toward Customer Loyaltynorhaya09Pas encore d'évaluation

- NOTA MATEMATIK Edited by MAZIAHDocument73 pagesNOTA MATEMATIK Edited by MAZIAHAnnaPas encore d'évaluation

- Students ' Perceptions and Behavior Toward On-Campus Foodservice OperationsDocument16 pagesStudents ' Perceptions and Behavior Toward On-Campus Foodservice Operationsnorhaya09Pas encore d'évaluation

- Factorsinfluencinghotelselection DecisionmakingprocessDocument60 pagesFactorsinfluencinghotelselection DecisionmakingprocessKhanPas encore d'évaluation

- MTK2 2018 UpsrDocument25 pagesMTK2 2018 Upsrnorhaya09Pas encore d'évaluation

- International Journal of Hospitality Management 77 (2019) 245-259Document15 pagesInternational Journal of Hospitality Management 77 (2019) 245-259norhaya09Pas encore d'évaluation

- Customer Satisfaction and Customer LoyaltyDocument73 pagesCustomer Satisfaction and Customer LoyaltySony Prabowo100% (3)

- Assessing The Internal Factors of Malay Ethnic Restaurants Business Growth PerformanceDocument12 pagesAssessing The Internal Factors of Malay Ethnic Restaurants Business Growth Performancenorhaya09Pas encore d'évaluation

- Research ArticleDocument11 pagesResearch Articlenorhaya09Pas encore d'évaluation

- Tourism Management: Sedigheh Moghavvemi, Kyle M. Woosnam, Tanuosha Paramanathan, Ghazali Musa, Amran HamzahDocument13 pagesTourism Management: Sedigheh Moghavvemi, Kyle M. Woosnam, Tanuosha Paramanathan, Ghazali Musa, Amran Hamzahnorhaya09Pas encore d'évaluation

- Online Food Delivery Services: Making Food Delivery The New NormalDocument17 pagesOnline Food Delivery Services: Making Food Delivery The New Normalnorhaya09Pas encore d'évaluation

- Social Culture Conflicts and TourismDocument15 pagesSocial Culture Conflicts and Tourismnorhaya09Pas encore d'évaluation

- Social Culture Conflicts and TourismDocument15 pagesSocial Culture Conflicts and Tourismnorhaya09Pas encore d'évaluation

- CH 7 Cole and Eriksson PDFDocument24 pagesCH 7 Cole and Eriksson PDFnorhaya09Pas encore d'évaluation

- Human Resource Management and Native People: A Checklist of Concerns and ResponsesDocument14 pagesHuman Resource Management and Native People: A Checklist of Concerns and Responsesnorhaya09Pas encore d'évaluation

- TourismConcern IndustryHumanRightsBriefing-FIN PDFDocument12 pagesTourismConcern IndustryHumanRightsBriefing-FIN PDFnorhaya09Pas encore d'évaluation

- Dive Tourism Hampton & Jeyacheya NVU HanoiDocument7 pagesDive Tourism Hampton & Jeyacheya NVU Hanoinorhaya09Pas encore d'évaluation

- Tourism and Local Economic DevelopmentDocument8 pagesTourism and Local Economic Developmentim_isolatedPas encore d'évaluation

- Beyond AuthenticityDocument18 pagesBeyond Authenticitynorhaya09Pas encore d'évaluation

- 07 Naser EgbaliDocument15 pages07 Naser Egbalinorhaya09Pas encore d'évaluation

- Art - Hornsey-2008 Self Categorization PDFDocument19 pagesArt - Hornsey-2008 Self Categorization PDFUmbelino NetoPas encore d'évaluation

- Briedenhann 04Document9 pagesBriedenhann 04Lunny BonkPas encore d'évaluation

- Tourism, Rural Development and Human Capital in Nepal: Martina Shakya Martina ShakyaDocument16 pagesTourism, Rural Development and Human Capital in Nepal: Martina Shakya Martina Shakyanorhaya09Pas encore d'évaluation

- Nasik 2Document418 pagesNasik 2patil_deeps234Pas encore d'évaluation

- DPR Metro Nov 2015Document515 pagesDPR Metro Nov 2015Manish DeyPas encore d'évaluation

- Seoul DirectoryDocument30 pagesSeoul DirectoryIzzah FarzanaPas encore d'évaluation

- CH 1Document14 pagesCH 1dcn2ncd7071Pas encore d'évaluation

- Types Catering EstablishmentsDocument3 pagesTypes Catering EstablishmentsManikant SAhPas encore d'évaluation

- Sod Revised 2004 Corrected Upto Cs-23 Final Updated On 22-3-18Document60 pagesSod Revised 2004 Corrected Upto Cs-23 Final Updated On 22-3-18Rajesh Verma100% (1)

- Summary of Control & Signaling Line2 (VOLUME1)Document30 pagesSummary of Control & Signaling Line2 (VOLUME1)m_afuni80Pas encore d'évaluation

- Modes of Transport and Railway EngineeringDocument113 pagesModes of Transport and Railway EngineeringSeetunya Jogi100% (4)

- Skybus MetroDocument3 pagesSkybus MetroAnjanKumarMahantaPas encore d'évaluation

- Revised SOD 2004Document71 pagesRevised SOD 2004Suraj PrakashPas encore d'évaluation

- Aedas Portfolio (Copyright Aedas)Document50 pagesAedas Portfolio (Copyright Aedas)arjun_menon_650% (2)

- G KDocument80 pagesG KJaved AkhtarPas encore d'évaluation

- Public Transportation Terminal Medium-Term Development Plan 5.1 Selection of The Priority ProjectsDocument18 pagesPublic Transportation Terminal Medium-Term Development Plan 5.1 Selection of The Priority ProjectsEmeil Bernard CalmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Swami Vivekananda Road NGEF Road Krishnayan Palya Road Railway Parallel RoadDocument10 pagesSwami Vivekananda Road NGEF Road Krishnayan Palya Road Railway Parallel RoadNethraa SkPas encore d'évaluation

- Train Station Design ThesisDocument8 pagesTrain Station Design Thesisyessicadiaznorthlasvegas100% (2)

- ANDC ReportDocument8 pagesANDC ReportSiddharth MPas encore d'évaluation

- Rt5161a Station Design and Maintenace Requirements PDFDocument20 pagesRt5161a Station Design and Maintenace Requirements PDFCezary P.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Map of Barcelona AirportDocument3 pagesMap of Barcelona AirportAndrei MateiPas encore d'évaluation

- Indian Railways Schedule of DimensionsDocument57 pagesIndian Railways Schedule of DimensionsradhakrishnanPas encore d'évaluation

- Aadi Amavasya SpecialDocument5 pagesAadi Amavasya SpecialjyoprasadPas encore d'évaluation

- Layout and Construction of A Railway Track and Railway StationDocument12 pagesLayout and Construction of A Railway Track and Railway StationAli Hassan LatkiPas encore d'évaluation

- Baiyappanhalli BriefDocument15 pagesBaiyappanhalli BriefsharikaPas encore d'évaluation

- Beijing ItineraryDocument38 pagesBeijing ItineraryReni RustamPas encore d'évaluation

- Thesis-Sustainable Transportation StrategiesDocument44 pagesThesis-Sustainable Transportation StrategiesHimanshu Saluja90% (10)

- BBC Sound Effects Library Original Series CD 1-40Document41 pagesBBC Sound Effects Library Original Series CD 1-40Slava FidelPas encore d'évaluation

- Taipei Itinerary PlanDocument5 pagesTaipei Itinerary Planyenny.angzas9139Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bartolome, Rohan Siegfried B. Arc 007 RSW No. 3 Regional Bus TerminalDocument51 pagesBartolome, Rohan Siegfried B. Arc 007 RSW No. 3 Regional Bus TerminalBartolome, Rohan Siegfried B.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mayumba-Tchibanga Line: Teiko National Railways Corporation BidDocument6 pagesMayumba-Tchibanga Line: Teiko National Railways Corporation BidJM SepePas encore d'évaluation