Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

A Conversation With CDPQ Michael Sabia

Transféré par

Vinit DawaneCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

A Conversation With CDPQ Michael Sabia

Transféré par

Vinit DawaneDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

2nix/iStock/Getty Images

A conversation with CDPQs

Michael Sabia

A leading institutional investor reflects on the industry.

Peter Bisson and Jonathan Ttrault

Michael Sabia joined la Caisse de dpt et placement

du Qubec (CDPQ) in 2009, at the depths of the

global financial crisis. Since then, the industry has

recovered, as has CDPQ, which now has $226 billion under management. In April 2015, he spoke with

McKinseys Peter Bisson and Jonathan Ttrault

about what hes learned in his six years on the job.

McKinsey on Investing: You joined CDPQ

at a difficult time for investors. What

was your approach to leading the organizations transformation?

Michael Sabia: First, we looked very closely

at the needs of the people whose assets we manage.

That was our starting pointwe wanted to

understand our depositors, their obligations, and

what kind of returns they needed in order to

A conversation with CDPQs Michael Sabia

meet them. Then, as is the case with all turnarounds, we broke the challenge we faced into two

questions: what to do and how to do it.

The what of the transformation was a new investment strategy, based on what we call a businessowner mind-set. Investing as a business owner is

the key to everything we do. We have a deeply

held belief that operations and operational excellencenot financial engineeringare the sources

of durable value creation. I think my experiences

working in two industrial companies before

joining CDPQ have influenced how I think about this.

Heres an example. When I got here, I met with

some of our transportation-research people and

I asked for a summary of a particular railroad

companys strategy for managing its rail yards. At

49

the time, they couldnt do itbut now they can. This

kind of information is important. What happens

in a rail yard is the source of service quality for railroads, and its the source of cost management. Its

fundamental to the creation of value in the business.

If you cant answer that question, you shouldnt

invest in railroads, because you cant differentiate

one company from another.

The how was about changing the culture of

the organizationthat is, how work gets done. This

change had three parts. One: we did a lot of work

on recruitment and personnel development. Two:

we created decision-making processes that are

more rigorous and collaborative. A big part of this

was breaking down silosthings like changing IT platforms so that the platforms themselves

support collaboration, which hadnt been the

case in the past. And the third part was a revamp

of our compensation program. This is important everywhere, but its particularly important in

an investment institution.

McKinsey on Investing: Can you expand on the

concept of the business-owner mind-set? What does

it mean for institutional investors like CDPQ?

Michael Sabia: If you own a business, you have

a deep knowledge of the fundamentalsknowledge

that goes way beyond the P&L and the balance

sheet. The fundamentals of the business involve, in

our minds, its culture, its people, its operations

essentially, the companys value drivers. Having a

business-owner mind-set also means understanding

Michael Sabia

Vital statistics

Born September 11, 1953, in

St. Catharines, Ontario

Education

Bachelor of arts in economics and

politics from the University of Toronto

Graduate degrees in economics and

politics from Yale University

Career highlights

La Caisse de dpt et placement

du Qubec

(2009present)

President and chief executive officer

Bell Canada Enterprises

(200208)

President and chief executive officer

Canadian National Railway

(199399)

Various roles, including chief financial

officer

50

McKinsey on Investing Number 2, Summer 2015

Fast facts

Member of the governing council of

Finance Montral

Former member, North American

Competitiveness Council

Honorary chairman of the Bal du Centre

hospitalier universitaire de Qubec

Cochair, Campaign for Centraide du

Grand Montral

the industry and the competition. And it means

being patient, too. But, of course, being patient

doesnt mean being complacent. We expect performance over the medium and longer term.

Now, how does that translate into the principles

of an investment strategy for a firm like us? It

means we have a strong preference for investing in

assets that people use every day and that are

rooted in the real economybuildings, ports, IT

services, consumer products, and so on. It also

means we stay focused on the intrinsic value of

a business, which is largely based on a deep

understanding of its operations, rather than getting

caught up in the smoke screen of its market value.

We stay focused on the fundamentals, rather than

relying on market indexes. In fact, were agnostic

about benchmarks.

Because of all of those things, and because of

the depth of analysis we do, we are very comfortable

taking concentrated positions without being

overly preoccupied with diversifying within each

portfoliobecause diversification has steeply

diminishing marginal returns. Our view is that the

best risk-management tool is deep diligence

not just due diligence, but deep diligence.

McKinsey on Investing: What does it mean to

be agnostic about benchmarks?

Michael Sabia: Take public equity, for instance.

The traditional approach starts with a market index

like the S&P 500. By and large, you buy the stocks

in the index and adjust the size of your position relative to their market weight depending upon what

you like and what you dont like. That style of investing assumes that the market itself is a compass

that shows where true north is. Well, I dont believe

that markets show you where true north is. I think

markets are subject to all kinds of vagaries and

exogenous influences. They often reflect fads, not

fundamentalsas they say, more noise than signal.

A conversation with CDPQs Michael Sabia

We dont believe that an index should be the starting

point for an investment process. A benchmarkagnostic approach means proceeding in a bottom-up

way, by focusing only on companies you like. In

other words, if you believe in fundamentals, and if you

believe in operational excellence as a source of value,

you build a portfolio from the bottom up, without

using the composition of a market as your compass.

So in late 2012, we started building a benchmarkagnostic portfolio in global, high-quality public

equities from the bottom up. Today its a $20 billion

portfolio, invested in about 70 different securities, and its performing well beyond our expectations.

Were committed to this path. Weve just recently

finished converting $20 billion in Canadian equities

to the same approach. Of course, investments

like real estate, infrastructure, and private equity

areor should beinherently benchmark agnostic.

When weve finished the conversion process a

couple of years from now, almost 80 percent of our

total portfolio assets will be managed this way.

McKinsey on Investing: You mentioned a difference between deep diligence and due

diligence. Can you talk a bit about your research

capabilities, then versus now?

Michael Sabia: The railroad story I shared earlier

is an example of the kind of thing weve changed.

Our people are able to answer those kinds of questions

nowdeep questions about the operations, strategy,

and vision of the companies were investing in. Weve

also hired geologists, mining engineers, people

with experience in consumer products, people with

experience in IT companiespeople who bring a

deep understanding of how value is created in each

of these sectors.

I think of it this way: an analysis of a P&L or a

balance sheet is like taking a photograph of a company. Its one-dimensional. Our approach to

research is more like an MRI. It goes beyond a single

51

dimension. If youre going to be a fundamentalsoriented investor with concentrated positions, you

have to go much deeper than a snapshot.

McKinsey on Investing: How were you able to

convince the different stakeholdersthe board, the

depositorsto embrace such a different approach?

McKinsey on Investing: How did you transform

these principlesdeep diligence, businessowner mind-setinto organizational changes?

Michael Sabia: First and foremost, its important

to remember that the financial crisis of 200809 was

very fresh in everyones memory. The need for

change was obvious. That made building a consensus around a long-term, fundamentals-based

investment strategy a lot easier. And as far as

becoming benchmark agnostic, whenever I met

our depositors or members of our board, I spent a lot

of time discussing this simple question: If there

are six Canadian banks, using the traditional investing logic youd underweight the three you dont

like and overweight the three you like. But if you dont

like three of them, why would you invest in

them at all? And the answer was always, Thats a

good question.

Michael Sabia: Obviously, the first element is

people. The change in research is one example of

a broader change in the profile of the people we

hire. All of our employees are financially capable, of

course, but we needed people who are comfortable letting go of indexes, investing for the long term,

and who have a deep grounding in operationsbe

it in companies, infrastructure, or real estate. More

than half of our 800 staff members are new since

2009. So theres been a substantial shift in the people

we hire. Thats one organizational change.

Its not just about new hires though. I dont think

the investment industry puts enough emphasis

on leadership. Good investors are not always good

leaders. So we spent a lot of time and effort on

building leadership and structuring compensation,

so that we got incentives pointing in the direction

we wanted to go.

Finally, in a turnaround situation, you have to take

specific steps that demonstrate to the organization that the changes youre suggesting are actually

doable. If that demonstration isnt done, the

organization will either have a lot of self-doubt, or it

will resist change because of the usual status

quo bias. For instance, the idea of a benchmarkagnostic portfolio was new at CDPQ. The success weve had so far in converting public equities

to this approach has been especially important

in mobilizing change because it signaled to the organization that it is, in fact, possible to step out of

the traditional thinking. This experience has made

it a lot easier to make other changes.

52

McKinsey on Investing Number 2, Summer 2015

That simple question took us pretty far. If youre

a fundamentals-oriented investor and you dont like

three banks, dont own them. It doesnt matter

that theyre in the index. We never had any serious

pushback from any of our stakeholders. On the

benchmark-agnostic issue, the biggest challenge

was internal. There were a lot of people in the

organization who just didnt believe the new strategy

was doable. Thats why it was so important to

take steps to demonstrate it was possible. We were

fortunate that the creation of the first benchmarkagnostic portfolio went so well and could serve

as proof.

McKinsey on Investing: Investors are deploying

more and more capital in alternative investments. Whats your sense of the rise in competition?

How is CDPQ approaching alternatives?

Michael Sabia: Increasing our exposure to

alternative assets is a centerpiece of our plan. That

said, when faced with a crowded market, you

have to differentiate. Capital is a commodity, its

not a differentiator. In our minds, our ability to

differentiate involves two things: how we analyze the

investment opportunity and the operational value

added that we bring.

Our work in real estate is a good example. Our subsidiary Ivanho Cambridge runs our $32 billion

real-estate portfolio. This is a group of 1,700 people

who not only invest in but also build and operate

shopping centers and office towers. Because of that,

because they are in the market, operating buildings, finding tenants, they have much deeper insights

into the intrinsic value of a property, beyond the

traded value of properties. Thats the analytics part.

The second point is that when we acquire a building,

alone or with partners, were not just bringing

capital to the table. Were bringing an operating capability that enriches the product. This is why

were planning to build a new subsidiary to handle

our infrastructure business in a manner that

will be similar to what we do in real estate. Again, it

comes back to operations. Investment expertise

is always important when it comes to differentiation,

but its not enough. Its about marrying investment and operational expertise.

McKinsey on Investing: Your new model for

infrastructure has attracted a lot of international

attention. What is it exactly, and whats your

plan for it? And can you say how it differs from the

classical publicprivate partnership?

Michael Sabia: As we all know, there is a tremendous need for new and better public infrastructure,

and not just in places like India and Chinathe

United States needs trillions of dollars of infrastructure, too. But governments are significantly limited

when it comes to providing that infrastructure

there are fiscal constraints and constraints from

indebtedness as well.

A conversation with CDPQs Michael Sabia

Our new platform will do several things. First,

it will take greenfield-infrastructure projects off

governments balance sheetsa significant

difference from typical publicprivate partnerships

while still safeguarding governments role in

defining a projects public-policy dimensions: where

its built, how big it is, how it will be priced, and

so on. Those are fundamental public-policy issues.

So this platform allows governments to act as

the guardian of the public interest but transfers the

execution and financial risk to us. We know that

managing those risks is a challenge. With the expertise weve built and with the right partners, we

believe it is very doable.

Second, the platform creates a one-stop shop for

all aspects of project development, financing, and

coordination, including a heavy emphasis on

tendering for every service so that costs stay low.

And finally, the new platform makes us responsible for ongoing operations of the infrastructure

project, which furthers the goal of keeping the

infrastructure off the government balance sheet.

As an institutional investor, we wont handle

operations ourselves; CDPQ will partner with worldclass infrastructure operators. This brings me

back to one of my earlier pointsthat operational

precision can have a big impact on the value

of the asset. The platform is in its early stages, but

were very encouraged by the amount of interest

it has been receiving, in the United States, Europe,

and elsewhere.

McKinsey on Investing: Your investment strategy

hinges on a deep understanding of the companies

in which you invest. Given that, is there a role for

external managers?

Michael Sabia: We manage 90 percent of our

assets internally, first because its essential for the

strategy to work and second because we believe

53

it isby farthe most economical way to manage.

Michael Sabia: Theres certainly an important

That said, we will continue to work with external

public-policy dimension to long-term capitalism.

managers in a few areas. First, well look for expertise

There are tax- and corporate-law changes that

in highly specialized areas where we just dont

are needed as well as changes in voting rights

have sufficient expertise, such as value investing in

a whole range of things. And those things are

emerging markets. Second, there are areas

both important and challenging. But these are going

distressed debt is a good examplewhere were

to take time. So I think we have the responsibuilding knowledge, but its not quite there yet.

bility to kick-start the process ourselves. We need

So we will continue to rely on the expertise of others

to just do it. Institutional investors like CDPQ

as were building up our own. And theres a third

and our counterparts, which have long-dated assets

area thats slightly more abstract. Increasingly we

managed in the interest of long-dated liabilities,

want to work with external experts in a way that

need to become much more visible, active, longensures were involved in decision making, especially

term investors.

in private equity. We want to be part of the process

itself. Being the recipient of external expertise is

So what does just doing it mean? Some things are

great, but working with outside experts also creates

simple, like changing the way we interact with

an opportunity for knowledge transfer. We want

the companies we operate or invest in. We shouldnt

to work with people who are going to give us an oppor- be asking a CEO to simply help fill in an earnings

tunity to learn and to participate; we dont want

model for the next two quarters. We should be asking,

to just write a check to someone else, who then goes

How do you manage talent development? What

about investing it.

are the biggest obstacles to your strategic plan for the

company? Whats it going to look like five years

More broadly speaking, I think partnerships are

from now? How can we help you get there?

the future of large-scale institutional investing.

Pension funds and sovereign funds are getting large

Having been the CFO of one publicly traded comenough that many of the organizations managing

pany and the CEO of another, I can tell you that the

them are now developing substantial expertise across

shareholders you hear from most often are only

many asset classes. As the industry evolves, were

worried about next week. The shareholders who are

going to see big transactions across all kinds of asset

thinking longer term tend to be less vocal. That

classes, through partnerships among long-term

has to change.

institutional investors. I think these partnerships

Peter Bisson (Peter_Bisson@McKinsey.com) is a

are going to become a bigger and more influential

director in McKinseys Stamford office, and Jonathan

voice in the capital market. So learning how to truly

Ttrault (Jonathan_Tetrault@McKinsey.com) is a director

partner with other organizations is a really imporin the Montral office.

tant part of building investment capability for the

future. It wont be possible to be a lone wolf anymore.

McKinsey on Investing: Youre a strong advocate

of long-term capitalism. In your view, what are the

changes that would most affect how capital-market

participants think about the balance between

short-term and long-term horizons?

54

McKinsey on Investing Number 2, Summer 2015

Copyright 2015 McKinsey & Company.

All rights reserved.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- My Country: By: Priyanka Dhanuka Rishabh Singh Rohini Deshmukh Suhani Mathur Upamanyu Roy Vaibhav PatilDocument24 pagesMy Country: By: Priyanka Dhanuka Rishabh Singh Rohini Deshmukh Suhani Mathur Upamanyu Roy Vaibhav PatilVinit DawanePas encore d'évaluation

- One Day at A Time....Document51 pagesOne Day at A Time....Abhinav LocPas encore d'évaluation

- Cottle-Taylor:: Expanding The Oral Care Group in IndiaDocument17 pagesCottle-Taylor:: Expanding The Oral Care Group in IndiaVinit DawanePas encore d'évaluation

- 80 eDocument1 page80 eVinit DawanePas encore d'évaluation

- Cottle-Taylor:: Expanding The Oral Care Group in IndiaDocument17 pagesCottle-Taylor:: Expanding The Oral Care Group in IndiaVinit DawanePas encore d'évaluation

- Why Men Said They Commited Rape: Total Result 196.9Document22 pagesWhy Men Said They Commited Rape: Total Result 196.9Vinit DawanePas encore d'évaluation

- Boeing - The Complete StoryDocument258 pagesBoeing - The Complete StoryAdrian Bistreanu100% (1)

- IoE Smart City PoVDocument21 pagesIoE Smart City PoVAdrian GrozavuPas encore d'évaluation

- FujitsuDocument23 pagesFujitsuVinit DawanePas encore d'évaluation

- BPR Session 2Document27 pagesBPR Session 2Vinit DawanePas encore d'évaluation

- Can India Lead The Mobile-Internet Revolution PDFDocument5 pagesCan India Lead The Mobile-Internet Revolution PDFanish1012Pas encore d'évaluation

- E Before I Why Engagement Needs To Come First in Planning InfrastructureDocument3 pagesE Before I Why Engagement Needs To Come First in Planning InfrastructureAnonymous JwIc3iLAgvPas encore d'évaluation

- BPR Session 1Document24 pagesBPR Session 1Vinit DawanePas encore d'évaluation

- Adhocracy For An Agile AgeDocument13 pagesAdhocracy For An Agile AgeVinit DawanePas encore d'évaluation

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Session 3 8 AM - 10 AM: Roles in BPR & Dimension TypesDocument13 pagesSession 3 8 AM - 10 AM: Roles in BPR & Dimension TypesVinit DawanePas encore d'évaluation

- Advanced Driver Assistance SystemsDocument11 pagesAdvanced Driver Assistance SystemsVinit DawanePas encore d'évaluation

- A Wake Up Call For Big Pharma PDFDocument6 pagesA Wake Up Call For Big Pharma PDFVinit Dawane100% (1)

- A Best Practice Model For Bank ComplianceDocument3 pagesA Best Practice Model For Bank ComplianceVinit DawanePas encore d'évaluation

- A Recipe For Economic Growth PDFDocument3 pagesA Recipe For Economic Growth PDFVinit DawanePas encore d'évaluation

- A Road Map To The Future For The Auto IndustryDocument11 pagesA Road Map To The Future For The Auto IndustryStradaPas encore d'évaluation

- A Streetcar Named ProductivityDocument8 pagesA Streetcar Named ProductivityVinit DawanePas encore d'évaluation

- A Digital Prescription For Pharma CompaniesDocument6 pagesA Digital Prescription For Pharma CompaniesVinit DawanePas encore d'évaluation

- A Hidden Roadblock in Public Infrastructure ProjectsDocument4 pagesA Hidden Roadblock in Public Infrastructure ProjectsVinit DawanePas encore d'évaluation

- A Conversation With Jim CoulterDocument6 pagesA Conversation With Jim CoulterPogotoshPas encore d'évaluation

- A Cost Curve To Improve Road SafetyDocument3 pagesA Cost Curve To Improve Road SafetyVinit DawanePas encore d'évaluation

- A Better Way To Understand Internal Rate of Return PDFDocument7 pagesA Better Way To Understand Internal Rate of Return PDFfshirani7619Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Conversation With Chamath Palihapitiya PDFDocument4 pagesA Conversation With Chamath Palihapitiya PDFVinit Dawane100% (1)

- A Billion Dollar Digital Opportunity For Oil CompaniesDocument5 pagesA Billion Dollar Digital Opportunity For Oil CompaniesVinit DawanePas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Adr SyllabusDocument2 pagesAdr SyllabusValerie TioPas encore d'évaluation

- Industrial Economics and Competitive StrategyDocument3 pagesIndustrial Economics and Competitive StrategyqwertyPas encore d'évaluation

- PPM 2016 02cont1 RudzaniDocument11 pagesPPM 2016 02cont1 RudzaniHAZELPas encore d'évaluation

- Plaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Defendants-Appellants Simplicio Del Rosario Joaquin Rodriguez SerraDocument4 pagesPlaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Defendants-Appellants Simplicio Del Rosario Joaquin Rodriguez SerraJennilyn Gulfan YasePas encore d'évaluation

- Master Circular On Rbi Circular - Circular On Forex Risk ManagementDocument95 pagesMaster Circular On Rbi Circular - Circular On Forex Risk ManagementBathina Srinivasa RaoPas encore d'évaluation

- CFM Tutorial 5Document26 pagesCFM Tutorial 5Nithin Yadav0% (1)

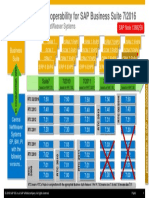

- Adjusted Version Interoperability 2016 V4 PDFDocument1 pageAdjusted Version Interoperability 2016 V4 PDFvsnetPas encore d'évaluation

- Examples TransferpricingDocument15 pagesExamples Transferpricingpam7779Pas encore d'évaluation

- Iberostar Grand Hotel Bavaro Inv #25468Document2 pagesIberostar Grand Hotel Bavaro Inv #25468David ArteagaPas encore d'évaluation

- Intermed Acc 1 PPT Ch02Document55 pagesIntermed Acc 1 PPT Ch02Rose McMahonPas encore d'évaluation

- List of Funds Offered by DBSDocument3 pagesList of Funds Offered by DBSmaheshlavandPas encore d'évaluation

- R3 Vietnam Agency Family Tree 2016Document1 pageR3 Vietnam Agency Family Tree 2016Baty NePas encore d'évaluation

- CH 15 Mini CaseDocument16 pagesCH 15 Mini CaseMahmud Mostakim TakrimPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 18 HomeworkDocument3 pagesChapter 18 HomeworkTracy LeePas encore d'évaluation

- Engleski LekcijeDocument10 pagesEngleski LekcijeMariaDevederosPas encore d'évaluation

- Compendium DPE Guidelines 2019 PDFDocument503 pagesCompendium DPE Guidelines 2019 PDFKrishna SwainPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 9 Cabrera Applied AuditingDocument5 pagesChapter 9 Cabrera Applied AuditingCristy Estrella50% (4)

- Chapter 5 - Meeting Guest NeedsDocument30 pagesChapter 5 - Meeting Guest NeedsMademozel MichaePas encore d'évaluation

- PhilipsDocument20 pagesPhilipsRishikhant100% (1)

- The Role of Investment Banking in IndiaDocument13 pagesThe Role of Investment Banking in IndiaGuneet SaurabhPas encore d'évaluation

- US Rare Earth Minerals, Inc. - 3/28/2012 Boventures Appointed As Investor RelationsDocument1 pageUS Rare Earth Minerals, Inc. - 3/28/2012 Boventures Appointed As Investor RelationsUSREMPas encore d'évaluation

- Entrepreneurial Development Question Paper SolvedDocument39 pagesEntrepreneurial Development Question Paper SolvedKovid Garg100% (3)

- Bank Code ListDocument61 pagesBank Code Listjosephngoc90Pas encore d'évaluation

- IFRS Adoption Process A Case Study in PT. Total Bangun Persada TBK PDFDocument10 pagesIFRS Adoption Process A Case Study in PT. Total Bangun Persada TBK PDFUlfah KhairrunnisaPas encore d'évaluation

- Conceptual FrameworkDocument19 pagesConceptual FrameworkRej Villamor100% (2)

- Cuture AssignmentDocument5 pagesCuture Assignmentvisha183240100% (1)

- Risk Management of SbiDocument30 pagesRisk Management of SbiTanay Pandey100% (2)

- Nov 2014Document9 pagesNov 2014SANTHAPas encore d'évaluation

- An Analysis of The Strategic ChallengesDocument34 pagesAn Analysis of The Strategic ChallengesBenny HendartoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Top 100 Powerful CEO's in IndiaDocument3 pagesThe Top 100 Powerful CEO's in IndiavavPas encore d'évaluation