Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Mission Possible Developing EffectiveEducation Partnerships

Transféré par

Teo TeodoraCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Mission Possible Developing EffectiveEducation Partnerships

Transféré par

Teo TeodoraDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, Volume 7, Numbers 1&2, p.

79, (2001-02)

Mission Possible: Developing Effective

Educational Partnerships

Linda C. Cunningham and Lisa A. Tedesco

Abstract

This paper discusses some of the basic principles essential

for institutions of higher education in establishing and sustaining

an effective partnership with a K-12 public school system. The

Health Occupations Partners in Education (HOPE) project was

launched in 1998 as one of the Health Professions Partnership

Initiatives of the Association of American Medical Colleges.1

This initiative encourages health professional schools, local community organizations, and health care industry to partner with a

local K-12 public school district to increase the numbers of

underrepresented minority students interested in and academically prepared to pursue higher education and future careers in

the health professions. The partnership we have established via

HOPE brings together health professional schools, a local community college, local industry, and community organizations to

collaborate with a high school and two middle schools. We

describe some of the general principles and strategies we have

utilized to establish our partnership and to engage partner organizations in our school-based community outreach work.

What Do We Mean by Partnership?

efore we begin a discussion of what makes an effective

partnership, we feel it is helpful to define what we mean

by partnership with public schools. The meaning of partnership

may vary depending on the person, group, or organization involved.

Arriving at a common understanding of the concept of a partnership

is an important first step for anyone or any organization considering

forming a partnership with a public school or school district.

Partnerships of institutions of higher education, businesses,

community organizations and K-12 schools can be traced to the

earliest days of public education and offer rich opportunities for

improved student learning and academic achievement (Restine 1996;

Cordeiro and Kolek 1996). Unlike the traditional business-school

educational partnerships, which are typically charitable in nature

The Health Professions Partnership Initiative of the Association of

American Medical Colleges is made possible through grant funding from

the W. K. Kellogg and Robert Wood Johnson Foundations.

80 Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement

with the business partner agreeing to provide the school or school

district with supplemental resources or services at no charge, effective educational partnerships today entail active participation and

reciprocity among multiple partners to achieve common goals (Cordeiro and Kolek 1996). Partnerships that incorporate a collaborative

and consensus-based decision-making process are also recognized

as being among the most effective and successful in improving

educational outcomes for students (National Association of Partners

in Education 2001).

Development of an Effective Partnership

The Health Occupations Partners in Education (HOPE) partnership was initially conceived in 1997 when the Association of

American Medical Colleges (AAMC) announced new grant-funding

opportunities available to U.S. medical schools through the Health

Professions Partnership Initiative. This initiative encourages U.S.

medical schools to join with other health professional and

postsecondary schools and colleges, local community colleges,

health care industry, and

various local community orOur partnership is designed ganizations and professional

associations to address the

to increase the numbers of

lack of diversity in the health

underrepresented minority

professions by extending the

students interested in and

educational health profesacademically prepared for

sions pipeline into secondary

and elementary school years.

postsecondary education

Specifically, HOPE is an

and, ultimately, careers in

educational partnership with

the health professions.

the Ypsilanti Public Schools

(Ypsilanti High School, East

and West Middle Schools),

the University of Michigan (Schools of Dentistry, Education, Medicine, Nursing, Pharmacy, Public Health, Social Work; the UM

Health System; and six student organizations), Washtenaw Community College, Pfizer, and several local community organizations.

Our partnership is designed to increase the numbers of underrepresented minority students interested in and academically prepared

for postsecondary education and, ultimately, careers in the health professions. With so many different organizations joining together on one

project for the first time, it was essential that certain principles be

followed during the earliest stages of formation of this new partnership.

Developing Effective Educational Partnerships 81

Much is already known about the characteristics and underlying

principles of successful educational partnerships (Essex 2001;

Turbowitz and Longo 1997; Maeroff, Callan, and Usdan 2001; Ackerman

and Cordeiro 1996; Epstein et al. 1997; Otterbourg 1986; Byrne 2000;

National Association of Partners in Education 2001). We have found

that developing an educational partnership based on the following

principles has been essential to the early success of the HOPE project,

and positions us well for future development and sustainability.

Clearly Defined and Shared Purpose: The various individuals and

organizations involved in formation of the partnership must agree

on the overall direction and purpose of the partnership. Although

this may seem to be a commonsense approach to any collaboration

between independent groups, it is not unusual for partnerships to

struggle or even fail in the implementation stage when clear consensus among the various partners is lacking. Accordingly, it is

important that adequate time be devoted at the inauguration of any

new partnership initiative to defining a shared purpose or creating

a mission statement for the partnership. In the case of HOPE, the

mission statement or purpose of the project was already set forth

by the AAMC through the Health Professions Partnership Initiative.

Our task was to identify and recruit those partner organizations

that embraced this mission as their own.

Strong Commitment and Visible Support From Leaders: Endorsement and visible support from the leadership of each and every

partner organization or constituent group is critical to building

program and partnership capacity. Strong and visible commitment

and support from the top leadership of a partner organization can

be very helpful in facilitating institutional buy-in throughout the

ranks of their organizations, but this does not guarantee the full

and necessary engagement and participation of the organizations

members in the partnership endeavors. Often top leadership support

is not enough to foster adequate buy-in for a new program or initiative. Some organizations and communities have a more grassroots

leadership infrastructure in place, which enables individual leaders

at lower administrative levels of an organization or community

group to emerge as ambassadors for the new project or program

being developed. For example, the full support and commitment

of the superintendent of a local school district does not necessarily

translate into genuine support and commitment from school district

principals, teachers, and parents. Finding strong advocates to serve

as ambassadors for the new project at various levels throughout

the organization is important. When top-level leadership has not

82 Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement

yet demonstrated institutional commitment to the partnership endeavors, this strategy to enlist support among key constituents

within the organization can be effective in bringing the value of

this partnership to the top-level administration. In other words, and

to paraphrase a familiar expression, when the people lead, the

leaders will follow.

Shared Decision-making Power Among Partners: The approach

we have taken to the governing structure of the HOPE project has

been a defining element of our success in working with so many

different partner organizations and a local K-12 public school district. The HOPE partnership has a formal governing body, called

the HOPE Partnership Council, composed of representatives from

each of our partner organizations. The council meets at least quarterly and provides a forum for all

partners to communicate directly

with each other about current and

[W]e established this future project directions. Although

governing structure to the administering fiscal agent for

ensure that every

HOPE is the University of Michipartner organization

gan Medical School, we established

has an equal voice and this governing structure to ensure

that every partner organization has

vote in matters

an

equal voice and vote in matters

pertaining to project

pertaining

to project design, impledesign, implementation,

mentation, and evaluation. To build

and evaluation.

trust across our various partners

and to ensure adequate representation of different perspectives

within one organization, we have

representatives serving on the Partnership Council from several

different levels within one partner organization. For example, our

Partnership Council initially had one school district representative,

the superintendent. Because of the diverse perspectives held by

many of our school district partners and the demanding schedule

of the districts superintendent, communication was not always adequately channeled from the superintendent to the principals, and

subsequently from the principals to the teachers. Likewise, parents

of students in the school district also bring unique and valuable

perspectives to bear, and their voices were not always represented.

Accordingly, we have seats on our Partnership Council for the

district superintendent, the principal and two teachers from each

partner school, and a parent representative from each partner school.

Developing Effective Educational Partnerships 83

Reciprocity: Our experience, like that of Trubowitz and Longo

(1997), has taught us that an effective and enduring educational

partnership entails the pursuit of mutually beneficial self-interests

across all collaborating partners. At the micro level, the most dedicated volunteers working with K12 education are most often those

who experience personal and/or professional benefits as a direct

result of their volunteer service. Similarly, but at a macro level,

organizations are most likely to engage in the educational partnership endeavors when their

mission, values, and culture

support such efforts and when Adequate time must be

there are clear, direct and

devoted at the inauguration

tangible rewards for their participation as an institution. of any new partnership to

For example, one of the many identify the benefits each

benefits of partnership and partner organization wants

participation with HOPE rec- and needs to secure their

ognized by members of the stakehold in the work at

University of Michigans hand.

Black Pre-Med Student Association (BPMA) is the opportunity for them to engage in

meaningful community service with younger minority students in

the health professions pipeline. The BPMA students not only have

an opportunity to experience the personal satisfaction of giving

back to their communities by mentoring a younger person toward

his or her dream of college and a future health career, but also

perform a community service that is weighed favorably during

the medical school admissions process. Of course, the mission,

values, and culture of an organization will have a strong influence

on what it perceives to be meaningful incentives and benefits for

engaging in partnership work. The same holds true for any individual choosing to participate. Adequate time must be devoted at

the inauguration of any new partnership to identify the benefits

each partner organization wants and needs to secure their stakehold

in the work at hand.

Trubowitz and Longo caution us against forming partnerships

in the midst of initial enthusiasms and missionary zeal, and we

agree. They quote Goodlad (1994) to emphasize the importance of

addressing the reciprocal interests of each partner organization as

a necessary means to the development of a truly meaningful and

enduring educational partnership:

84 Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement

Because education is essentially a helping profession, the

tendency in seeking a partnership is to do good. Yet relationships built on benign intentions tend to be fleeting.

There is a greater potential in first seeing in the other

partner a source of satisfying ones own needs. If there is

a touch of cynicism here, so be it; but it is more a recognition of realities. And there is another important reality

closely related: if in seeking satisfaction of ones own need,

the needs of the partners are ignored, the partnership will

soon dissolve.

Given the scope and breadth of

organizations and institutions

Without consideration

represented in the HOPE partnership, and that this partnership and response to the

marks the first time all of these specific interests and

organizations joined together to needs of the school

work on a community-based district and community

project, it was important for us partners, distrust will

to develop a strategic plan that build and the partnership

would ensure the fulfillment of all is unlikely to develop.

partner interests and expectations.

Since HOPE is a communitybased project, it was particularly

important that the interests and needs of our community stakeholders

be central to the partnership. Without consideration and response to

the specific interests and needs of the school district and community

partners, distrust will build and the partnership is unlikely to develop.

Trust: Schools have often participated in educational projects or

reform efforts initiated by college and university faculty from which

the students, parents, and teachers feel they have received little or

no benefit. College faculty engaging in work with local schools

and communities for the sole purpose of advancing their own

research and publication agendas without regard for the needs of

their target population will have a difficult time developing the

kinds of relationships with school and community partners that are

necessary to foster a mutually beneficial long-term educational partnership. The issue of trust was of particular significance in initiating

the HOPE partnership in Ypsilanti Public Schools and remains equally

important in our work today.

The community organizing efforts of Bob Moses (Moses and

Cobb 2001) as he began his grassroots education movement, now

Developing Effective Educational Partnerships 85

recognized nationally as the Algebra Project, to promote math

literacy and educational equity among underrepresented minority

youth relates to our own local efforts in launching the HOPE project.

As outsiders from the University of Michigan with a straightforward

agenda to advance the academic achievement and college preparation

levels of students of color, we encountered skepticism, distrust,

and resistance from several factions within the school district as

we worked to build a strong foundation and a viable infrastructure

for our project. Although many within the school district were indifferent and some were strongly opposed to this new initiative at

the outset, we identified a small group of parents, teachers, counselors, and administrators from the community and school district

who were very supportive collaborators during the initial stages of

program development. These collaborators were essential in helping us to promote HOPE as a worthwhile new initiative within the

school district, and to identify and recruit the first small cadre of

HOPE students from each of

our partner schools during the

19981999 school year. Once

[D]irect teacher

a small group of students and

engagement and support

parents began participating in

are

critical to the success

the program, positive news

and future sustainability of

about HOPE began to spread,

any partnership initiative

trust began to build, and teachaimed at improving

ers who were once indifferent

or opposed to the program

academic achievement,

started to become interested in

particularly among

the new opportunities available

disadvantaged and/or

to them and their students via

underrepresented students.

HOPE. In addition to the input

we solicited from students,

parents, and other community

partners, we also consulted

with teachers and school administrators frequently during the early

stages of the projects development to ensure they had adequate

and direct input into the overall design and implementation of the

project. This approach helped us to establish trust and gain support

among many school district teachers. Weve learned that direct

teacher engagement and support are critical to the success and

future sustainability of any partnership initiative aimed at improving

academic achievement, particularly among disadvantaged and/or

underrepresented students.

86 Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement

Sustainability: Effective educational partnerships take a long time

to build, and require strong and active commitment from many

stakeholders to bring about meaningful results. Depending on the

purpose and objectives of the educational partnership, it could take

many years or decades to achieve the goals of the partnership. We

agree with Dr. Shirley Jackson (2001), member of the National

Advisory Council for the Health Professions Partnership Initiative

at the Association of American Medical Colleges, who reminds us

to be aware of and responsive to issues of abandonment when

working with schools. School personnel, she explains, have had

too many experiences in which universities offer promises and programs, disrupt the schools routine, and leave the students, parents,

and teachers with nothing more than unmet needs and unkept

promises. Schools need to

know that the partnership

involves long-term comTo gain genuine support

mitment from all partners

to develop and implement

and trust . . . it is essential

meaningful solutions to

that partnerships incorporate

identified problems, and

a plan for sustainability and

that the school and comwork collaboratively to

munity partners will not

implement

it beyond the

once again be left high and

initial start-up phase of any

dry after the groundwork

new project.

for initial relationships has

been laid. To gain genuine

support and trust among

partners, particularly school

and community partners, it is essential that partnerships incorporate

a plan for sustainability and work collaboratively to implement it

beyond the initial start-up phase of any new project.

Conclusion

As more universities begin to recognize and embrace the value

of engagement and partnership with local communities and public

schools to improve educational equity and opportunities for all

students, attention should be focused on some of the principles

known to underlie effective educational partnerships. Although the

Health Occupations Partners in Education project is still relatively

young, we have utilized the principles discussed in this paper with

much success to guide our partnership development process. The past

four years have presented us with many challenges, opportunities,

Developing Effective Educational Partnerships 87

and rewards as we have worked together to establish a strong

foundation and to build a viable infrastructure for our educational

outreach initiative within the local community and school district

of Ypsilanti, Michigan. The important work we have begun would

not be possible without the ongoing commitment, support, and resources from our many diverse HOPE partner organizations and

individual supporters. As we approach our fifth year of project

implementation, and our final year of the initial grant funding from

the Association of American Medical Colleges, we are directing

increased attention and efforts toward strategies to sustain the

critical work we have begun in the Ypsilanti community. The diligent

and often painstaking efforts involved in laying the groundwork

and building the trust necessary for an enduring and effective

school-university partnership can be for naught if the trust of the

community, so difficult to earn, is broken when start-up funding

for the project ends. For this reason it is especially important for

all partners, particularly community and school district partners,

to have a sense of ownership or a real stakehold in the partnership.

The days of school and community partners being the willing (or

sometimes reluctant), yet disempowered, recipients of supplemental

educational resources and services from well-meaning partners in

higher education or industry are over. Our community and school

partners bring unique and invaluable interests, perspectives, and

assets to the partnership. A shared purpose, support from leadership

(top-down or bottom-up), shared decision-making power, and reciprocal benefits are just some of the characteristics we have found to

be essential in building trust and a true esprit de corps among our

various HOPE partners. We believe the work we have begun via

HOPE, like that of so many other universities to engage in meaningful partnerships with their local communities, is revolutionary, yet

it does not use magic. Progress is made one relationship at a time

and requires collaboration, determination, and perseverance among

all partners to meet challenges together when they arise.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to recognize and thank the following individuals and organizations for their support of the HOPE project:

Allen S. Lichter, M.D., Dean, University of Michigan Medical School;

Joyce Sutton, Program Manager, HOPE; The HOPE Partnership

Council; Ypsilanti Public Schools; Association of American Medical Colleges, Division of Community and Minority Programs; the

W.K. Kellogg Foundation; and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

88 Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement

References

Ackerman, R., and P. Cordeiro, eds. 1996. Boundary crossings: Educational partnerships and school leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass

Publishers.

Byrne, J. 2000. Engagement: A defining characteristic of the university of

tomorrow. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 6(1):

13-21.

Cordeiro, P., and M. Monroe Kolek. 1996. Introduction: Connecting school

communities through educational partnerships. In Boundary crossings:

Educational partnerships and school leadership, edited by R. Ackerman

and P. Cordeiro, 114. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Epstein, J. L., L. Coates, K. Clark Salinas, M. G. Sanders, and B. S. Simon.

1997. School, family, and community partnerships: Your handbook for

action, Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press.

Essex, N. L. 2001. Effective school-college partnerships, a key to educational

renewal and instructional improvement. Education 121(4): 73236.

Goodlad, J. I. 1994. Educational renewal: Better teachers, better schools.

San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Jackson, S. 2001. Presentation at the third annual joint meeting of the Health

Professions Partnership Initiative (HPPI) and Minority Medical Education Program (MMEP) at the Plaza San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas.

Maeroff, G. I., P. M. Callan, and M. D. Usdan, eds. 2001. The learning connection: New partnerships between schools and colleges. New York:

Teachers College Press.

Moses, R. and C. E. Cobb, Jr. 2001. Radical equations: Math literacy and

civil rights, Boston: Beacon Press.

National Association of Partners in Education. 2001. Partners in Education

Partnership Development Process. Alexandria, VA.: National Association of Partners in Education.

Otterbourg, S. D. 1986. School partnerships handbook: How to set up and

administer programs with business, government, and your community,

Inglewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Restine, N. L. 1996. Partnerships between schools and institutions of higher

education. In Boundary crossings: Educational partnerships and school

leadership, edited by R. Ackerman and P. Cordeiro, 3140. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Trubowitz, S. and P. Longo. 1997. How it worksinside a school-college

collaboration, New York: Teachers College Press.

About the Authors

Linda C. Cunningham is the director of the Health Occupations

Partners in Education (HOPE)/Health Professions Partnership

Initiative at the University of Michigan and Ypsilanti Public

Schools. This initiative aims to increase the numbers of underrepresented minority students interested in and academically

prepared to pursue higher education and careers in the health

professions. Prior to joining the University of Michigan in 1998,

Ms. Cunningham worked as a volunteer recruitment and training specialist in the community outreach and health education

Developing Effective Educational Partnerships 89

divisions of the Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute in Detroit, Michigan. She earned her bachelor of arts degree from

Purdue University in 1992, and her masters degree in social

work from the University of Georgia in 1995 with a concentration

in children, youth, and family practice in a school-based community setting. She is a member of the National Association of

Partners in Education.

Lisa A. Tedesco is the interim provost and executive vice president for academic affairs, vice president and secretary of the

university, and professor of dentistry, at the University of Michigan. Dr. Tedesco is a member of the University of Michigan

Presidents Advisory Commission on Womens Issues and has

served as special advisor to the president on diversity. She was

responsible for coordinating the publication Climate and Character, which summarizes diversity initiatives at the University

of Michigan prior to 1997. She chairs the Campus Safety and

Security Advisory Committee, and also serves on the Faculty

and Staff Assistance Program Advisory Board and the Board in

Control of Intercollegiate Athletics.

Dr. Tedesco has worked in academic dentistry for over eighteen years in the areas of behavioral science, curriculum and

faculty development. From 1992 to 1998 she served as associate

dean for academic affairs at the School of Dentistry at the University of Michigan. Her research and scholarship interests are in

the areas of cognitive and behavioral enhancement of oral health

status; stress and oral disease; and curriculum, learning, and

teaching in the health professions. She has published widely in

these areas and presents her work at national and international

meetings. She is co-principal investigator of the University of

Michigan Health Occupations Partners in Education (HOPE)

project funded through the Association of American Medical

Colleges Health Professions Partnership Initiative.

Dr. Tedesco earned her masters degree in education in 1975

and her doctorate in educational psychology in 1981, both from

the State University of New York at Buffalo. In 1998 she was

the recipient of the Distinguished Alumni Award from the State

University of New York at Buffalo, Graduate School of Education.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Unicef Qualityeducation enDocument20 pagesUnicef Qualityeducation enTeo TeodoraPas encore d'évaluation

- Preschool Learning Pack: AirplanesDocument21 pagesPreschool Learning Pack: AirplanesTeo TeodoraPas encore d'évaluation

- Practica Ed. FizicaDocument1 pagePractica Ed. FizicaTeo TeodoraPas encore d'évaluation

- Kindergarten CurriculumDocument65 pagesKindergarten Curriculumapi-188945057Pas encore d'évaluation

- Early Childhood Education and Care Pedagogy Review EnglandDocument114 pagesEarly Childhood Education and Care Pedagogy Review EnglandTeo TeodoraPas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5795)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Jennifer E Shook (Jen Shook) CVDocument6 pagesJennifer E Shook (Jen Shook) CVjen_shookPas encore d'évaluation

- New Subjects of ICMAB SyllabusDocument3 pagesNew Subjects of ICMAB SyllabusPratikBhowmick100% (2)

- Sap+Etabs Training KolkataDocument3 pagesSap+Etabs Training KolkataSowmya MajumderPas encore d'évaluation

- Advising Student OrientationDocument38 pagesAdvising Student OrientationbocfetPas encore d'évaluation

- John PhamDocument18 pagesJohn PhamAlex MateiPas encore d'évaluation

- AIS1501 302 - 2017 - 4 - BDocument7 pagesAIS1501 302 - 2017 - 4 - BLeigh MakanPas encore d'évaluation

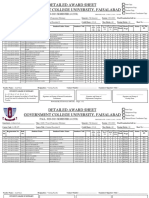

- Detailed Award Sheet Government College University, FaisalabadDocument2 pagesDetailed Award Sheet Government College University, FaisalabadNABEEL REHMANPas encore d'évaluation

- Deconstructing The Lone Genius Myth Towa PDFDocument45 pagesDeconstructing The Lone Genius Myth Towa PDFFabPas encore d'évaluation

- Uni Course Maths PrerequisitesDocument2 pagesUni Course Maths Prerequisitesmathsman9Pas encore d'évaluation

- En 22 201701Document1 pageEn 22 201701Jennilyn HenaresPas encore d'évaluation

- UNF Unofficial Transcript 2014Document9 pagesUNF Unofficial Transcript 2014Megan AllenPas encore d'évaluation

- Mem MPM Programme Guide 2015 Rev 00 3.Zp44129Document28 pagesMem MPM Programme Guide 2015 Rev 00 3.Zp44129NuuraniPas encore d'évaluation

- Start Up Grant FacultyDocument4 pagesStart Up Grant FacultyVishnu KonoorayarPas encore d'évaluation

- Sociology IIIDocument2 pagesSociology IIIPradhyumna B.Ravi100% (2)

- Triumphant College 2019 Award List Min 1 PDFDocument9 pagesTriumphant College 2019 Award List Min 1 PDFAbel KoitiPas encore d'évaluation

- International Relations Is The Study of Relationships Among Different CountriesDocument2 pagesInternational Relations Is The Study of Relationships Among Different CountriesCurtis GrahamPas encore d'évaluation

- DEnM 322 Course SyllabusDocument2 pagesDEnM 322 Course SyllabusRyan John de LaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Letter of Motivation: St. Patricks'S High School SecunderabadDocument3 pagesLetter of Motivation: St. Patricks'S High School SecunderabadsaikrishPas encore d'évaluation

- Onyeji Thecla Onyemauche: Personal InformationDocument2 pagesOnyeji Thecla Onyemauche: Personal Informationonyeji theclaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sejarah Peninjau JelebuDocument11 pagesSejarah Peninjau JelebuTengku Puteh Tippi100% (1)

- University of Cape TownDocument10 pagesUniversity of Cape TownJedd ShneierPas encore d'évaluation

- Vtu 2018-19 RegulationDocument21 pagesVtu 2018-19 RegulationAnonymous Vm6APkTEPas encore d'évaluation

- Quality Assurance ManualDocument113 pagesQuality Assurance ManualSehrish Mohsin100% (1)

- MBA Project Front PagesDocument7 pagesMBA Project Front PagesMd HassanPas encore d'évaluation

- NICMAR Distance Education Details PDFDocument13 pagesNICMAR Distance Education Details PDFShashank RajaPas encore d'évaluation

- Flowchart PHDDocument1 pageFlowchart PHDresurrection786Pas encore d'évaluation

- Doctoral Programme UKMGSBDocument4 pagesDoctoral Programme UKMGSBWai HongPas encore d'évaluation

- Civil TrainingProgDocument7 pagesCivil TrainingProgarjunPas encore d'évaluation

- Format For Mini ProjectDocument5 pagesFormat For Mini ProjectSavantPas encore d'évaluation

- Ug Catalog 2018 2019 PDFDocument399 pagesUg Catalog 2018 2019 PDFNader OkashaPas encore d'évaluation