Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Rem Compiled Final

Transféré par

Harold B. LacabaDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Rem Compiled Final

Transféré par

Harold B. LacabaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

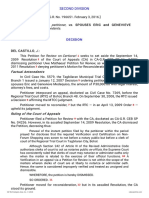

Justice Teresita Leonardo-De Castro Cases (2008- Remedial Law

2015)

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

INTERPRETATION OF THE PROVISIONS OF THE RULES OF COURT

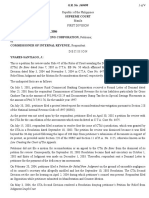

PCI LEASING and FINANCE, INC. vs. ANTONIO C. MILAN, Doing Business Under the Name and

Style of "A. MILAN TRADING," and LAURA M. MILAN

G.R. No. 151215, April 5, 2010, J. LeonardoDe Castro

A final and executory judgment, under the doctrine of immutability and inalterability, may no

longer be modified in any respect either by the court which rendered it or even by the Supreme Court.

However, as rules of procedure are mere tools designed to facilitate the attainment of justice, their

strict and rigid application, which would result in technicalities that tend to frustrate rather than

promote substantial justice, must always be eschewed. Thus, in the absence of a pattern or scheme to

delay the disposition of the case or a wanton failure to observe the mandatory requirement of the rules

on the part of the plaintiff, courts should decide to dispense with rather than wield their authority to

dismiss.

Facts:

PCI Leasing and Finance, Inc. (PCI Leasing) extended loans against herein respondents

Antonio C. Milan (Antonio) and Laura M. Milan. As such, the latter executed Deeds of Assignment in

which they assigned and transferred to the former their rights to various checks for and in

consideration of the various amounts obtained. Subsequently, when presented for payment, those

checks were dishonored for different reasons. Despite repeated demands, respondents failed to

settle their obligation, which amounted to P2,327,833.33 as of January 15, 2000. PCI Leasing was

then compelled to litigate to enforce payment.

On March 2, 2000, the RTC issued summons to respondents addressed to their place of

residence as stated in the complaint which were, however, returned unserved. As such, PCI Leasing

filed a Motion to Archive Civil Case No. Q-00-40010 subject to its reinstatement after the

whereabouts of the respondents was determined. It was denied by the RTC and on July 13, 2000, it

issued an Order, directing PCI Leasing "to take the necessary steps to actively prosecute the instant

case within ten days from receipt" under pain of dismissal of the case "for lack of interest." Thus,

PCI Leasing filed a Motion for Issuance of Alias Summons, which was, however, also denied on the

ground of a defective notice of hearing. Another similar motion was thereafter filed by PCI Leasing

and the same was scheduled for hearing on October 13, 2000. However, on said date, there was no

appearance from both counsels of the parties. Accordingly, the RTC issued an Order dismissing Civil

Case No. Q-00-40010. PCI Leasing sought a reconsideration of the said Order, explaining that its

counsel was already in the courtroom when Judge Leah S. Domingo-Regala of the RTC was dictating

the order of dismissal. However, the same was also denied. On January 26, 2001, PCI Leasing filed

an Ex Parte Motion for Reconsideration which was also denied by the RTC.

PCI Leasing eventually filed a Notice of Appeal which was also dismissed by the RTC by way

of a Resolution, given that it was filed beyond the reglementary period. Thus, it resorted into filing a

Petition for Certiorari under Rule 65 of the Rules of Court before the Court of Appeals, which was

however, dismissed outright for having been taken out of time. As its Motion for Reconsideration

Page 1 of 350

Justice Teresita Leonardo-De Castro Cases (2008- Remedial Law

2015)

with the CA was also denied, it elevated this case to the Supreme Court by way of the instant

Petition for Review on Certiorari under Rule 45.

With the SC, despite numerous attempts of PCI Leasing of determining the respondents'

address, the latter has been consistent in refusing to accept the summons and to file a comment to

the petition despite the Resolutions ordered by the Court and notwithstanding the penalty of fine

imposed for non-compliance of those. As such, on June 27, 2005, the Court resolved that: 1) the

copies of the said resolutions be deemed served; and b) an alias warrant of arrest against

respondent Milan be issued, directing the NBI to cause his immediate arrest and to detain him until

he complies with the said resolutions.

Eventually, Antonio Milan was arrested and detained by the NBI on March 24, 2006. Also, he

paid the fine earlier imposed upon him and filed an Explanation on Failure to File Comment with

Urgent Motion for Immediate Release from Detention with Prayer for Time to File Comment,

maintaining that he had not received any of the Resolutions of the Court, hence, the failure to abide

by the same. At the onset, the Court denied the said motion but it was eventually granted.

PCI Leasing, for its part, averred that both the lower courts defeated its right to recover the

sums of money it had loaned to the respondents simply because it allegedly committed "some

procedural lapses" in the prosecution of its case. It argued that if those rulings would be allowed to

stand, the respondents would allegedly be enriched at their expense. Thus, invoking for a liberal

application of the pertinent rules of procedure and invoking the inherent equity jurisdiction of

courts, it ultimately prays for the reinstatement of Civil Case No. Q-00-40010.

Issue:

Whether Civil Case No. Q-00-40010 should be reinstated.

Ruling:

We grant the petition.

The Court of Appeals indeed committed a mistake in issuing the Resolutions which

dismissed outright the Petition for Certiorari filed by PCI Leasing and denied the latters Motion for

Reconsideration. To recall, it based the dismissal of the Petition for Certiorari on the fact that (1)

the appeal of PCI Leasing was filed out of time and (2) the Notice of Appeal supposedly involved

pure questions of law.

As to the second ground, the CA was mistaken in concluding that the Notice of Appeal

involved pure questions of law on the basis of the statement therein that the Order and Resolutions

of the RTC would be appealed to it on the ground that the same were "contrary to the applicable

laws and jurisprudence on the matter." It was unreasonably hasty in inferring its lack of jurisdiction

over the intended appeal of PCI Leasing. It is only after the specific issues and arguments of PCI

Leasing are laid out in detail before the CA in the appropriate substantive pleading can it make a

conclusion as to whether or not the issues raised therein involved pure questions of law.

The first ground which was in concurrence with the findings of the RTC that the Notice of

Appeal was filed one day late was correct, but the premise therefor was evidently mistaken. In

Page 2 of 350

Justice Teresita Leonardo-De Castro Cases (2008- Remedial Law

2015)

accordance with the ruling rendered in the case of Neypes v. Court of Appeals, a party litigant may

either file his notice of appeal within 15 days from receipt of the RTCs decision or file it within 15

days from receipt of the order (the "final order") denying his motion for new trial or motion for

reconsideration. Obviously, the new 15-day period may be availed of only if either motion is filed;

otherwise, the decision becomes final and executory after the lapse of the original appeal period

provided in Rule 41, Section 3. In the case at bar, PCI Leasing filed a Motion for Reconsideration of

the RTC Order which dismissed Civil Case No. Q-00-40010. On January 4, 2001, the RTC rendered a

Resolution, denying the same. As said Resolution was received by PCI Leasing on January 17, 2001,

the latter therefore should have filed its Notice of Appeal within 15 days from such date or until

February 1, 2001. However, it actually filed its Notice of Appeal on May 11, 2001 or 114 days after

receipt of the said Resolution. Contrary to the findings of the RTC, the period within which to file

the Notice of Appeal should not be reckoned from May 3, 2001, the date of receipt of the RTC

Resolution dated April 6, 2001, which denied the Ex Parte Motion for Reconsideration of PCI

Leasing, the latter being a prohibited pleading as it was in the nature of a second motion for

reconsideration.

Therefore, the RTC Order dated October 13, 2000, dismissing Civil Case No. Q-00-40010,

should be deemed final and executory. As such, under the doctrine of immutability and

inalterability of a final judgment, it may no longer be modified in any respect either by the court

which rendered it or even by this Court. The two-fold purpose of the said doctrine are: (1) to avoid

delay in the administration of justice and thus, procedurally, to make orderly the discharge of

judicial business and (2) to put an end to judicial controversies, at the risk of occasional errors,

which is precisely why courts exist. Controversies cannot drag on indefinitely. The rights and

obligations of every litigant must not hang in suspense for an indefinite period of time. However,

notwithstanding the said doctrine, the Court finds, after a thorough review of the records, that

compelling circumstances are extant in this case, which clearly warrant the exercise of our equity

jurisdiction. It has been settled that rules of procedure should be viewed as mere tools designed to

facilitate the attainment of justice. Their strict and rigid application, which would result in

technicalities that tend to frustrate rather than promote substantial justice, must always be

eschewed. To our mind, it will not serve the ends of substantial justice if the RTCs dismissal of the

case with prejudice on pure technicalities would be perfunctorily upheld by appellate courts

likewise on solely procedural grounds, unless the procedural lapses committed were so gross,

negligent, tainted with bad faith or tantamount to abuse or misuse of court processes. In this

instance, PCI Leasing would be left without any judicial recourse to collect the amount of

P2,327,833.33 it loaned to the respondents. Corollarily, if PCI Leasing would be forever barred from

collecting the aforesaid amount, respondent Milan stands to be unjustly enriched at the expense of

PCI Leasing.

Also, it is important to note that the hearing in which the counsel of PCI Leasing came late

was merely for the issuance of Alias Summons. It was not even for the presentation of the evidence

in chief of PCI Leasing, where the latters presence would be indispensable. Incidentally, the Motion

for Issuance of Alias Summons filed by PCI Leasing is non-litigious in nature, which does not require

a hearing under the Rules, as the same could have been acted upon by the RTC without prejudicing

the rights of the respondents. Thus, it was serious error on the part of the trial court to have denied

the first motion for issuance of alias summons for want of notice of hearing. It was also not

mandatory for the trial court to set the second motion for hearing. However, despite all of these, the

RTC still dismissed the case and eventually denied the Motion for Reconsideration thereof. While

trial courts have the discretion to impose sanctions on counsels or litigants for tardiness or absence

Page 3 of 350

Justice Teresita Leonardo-De Castro Cases (2008- Remedial Law

2015)

at hearings, such sanctions should be proportionate to the offense and should still conform to the

dictates of justice and fair play. Moreover, It does not escape this Courts notice that PCI Leasing

failed to successfully prosecute the case for several months due to the difficulties it encountered in

locating respondents, who appeared to have a propensity for changing addresses and refusing to

accept court processes. Clearly, the delay in the trial court proceedings was not entirely the fault of

PCI Leasing.

The circumstances of this case do not constitute sufficient bases to warrant the conclusion

that PCI Leasing had lost interest in prosecuting Civil Case No. Q-00-40010. As such, in the absence

of a pattern or scheme to delay the disposition of the case or a wanton failure to observe the

mandatory requirement of the rules on the part of the plaintiff, as in the case at bar, courts should

decide to dispense with rather than wield their authority to dismiss.

CITY OF DUMAGUETE, HEREIN REPRESENTED BY CITY MAYOR, AGUSTIN R. PERDICES

vs. PHILIPPINE PORTS AUTHORITY

G.R. No. 168973, August 24, 2011, J. Leonardo-De Castro

Procedural rules were conceived to aid the attainment of justice. If a stringent application of

the rules would hinder rather than serve the demands of substantial justice, the former must yield to

the latter.

Facts:

Petitioner City of Dumaguete, through Mayor Felipe Antonio B. Remollo (Remollo), filed

before the RTC an Application for Original Registration of Title over a parcel of land with

improvements, located at Barangay Looc, City of Dumaguete under the Property Registration

Decree.

The RTC set the initial hearing of LRC Case No. N-201 and sent notices to the parties.

The Republic of the Philippines, represented by the Director of Lands, and Philippine Ports

Authority(PPA), represented by the Office of the Government Corporate Counsel, filed separate

Oppositions to the application for registration of City of Dumaguete. Both the Republic and PPA

averred that City of Dumaguete may not register the property in its name since the latter had never

been in open, continuous, exclusive, and notorious possession of the said property for at least 30

years immediately preceding the filing of the application; and the subject property remains to be a

portion of the public domain which belongs to the Republic.

However, before the next hearing, PPA filed a Motion to Dismiss, seeking the dismissal of

LRC Case No. N-201 on the ground that the RTC lacked jurisdiction to hear and decide the case. PPA

argued that Section 14(1) of Presidential Decree No. 1529, Property Registration Decree, refers

only to alienable and disposable lands of the public domain under a bona fide claim of ownership.

The subject property in LRC Case No. N-201 is not alienable and disposable, since it is a

foreshore land, as testified to by City of Dumaguete's own witness, Engr. Dorado. A foreshore land is

not registerable. This was the reason why the property was included in Presidential Proclamation

No. 1232 (delineating the territorial boundaries of the Dumaguete Port Zone), so that the same

would be administered and managed by the State, through PPA, for the benefit of the people.

Page 4 of 350

Justice Teresita Leonardo-De Castro Cases (2008- Remedial Law

2015)

In its Opposition to Oppositors Motion to Dismiss, City of Dumaguete claimed that the

property was a swamp reclaimed about 40 years ago, which it occupied openly, continuously,

exclusively, and notoriously under a bona fide claim of ownership. The technical description of the

property showed that the it was not bounded by any part of the sea. It invoked Republic Act No.

1899, which authorizes chartered cities and municipalities to undertake and carry out, at their own

expense, the reclamation of foreshore lands bordering them; and grants said chartered cities and

municipalities ownership over the reclaimed lands. Presidential Proclamation No. 1232 is

immaterial to the present application for registration because it merely authorizes PPA to

administer and manage the Dumaguete Port Zone and does not confer upon PPA ownership of the

property.

PPA filed a Reply/Rejoinder (To Applicants Opposition to Oppositors Motion to Dismiss),

asserting that there are no factual or legal basis for the claim of petitioner that the subject property

is reclaimed land. The present claim of City of Dumaguete that the property is reclaimed land

should not be allowed for it would improperly change the earlier theory in support of the

application for registration. PPA reiterated that the property is foreshore land which cannot be

registered; and that Presidential Proclamation No. 1232 is very material to LRC Case No. N-201

because it confirms that areas within the Dumaguete Port Zone, including the subject property, are

not alienable and disposable lands of the public domain.

On September 7, 2000, the RTC issued an Order granting the Motion to Dismiss of PPA. It

having been shown by City of Dumaguete's own evidence that the lot subject of the application for

original registration is a foreshore land, and therefore not registerable, the application must be

denied. The admission by Engr. Dorado that there is no formal declaration from the executive

branch of government or law passed by Congress that the land in question is no longer needed for

public use or special industries x x x further militates against the application. The RTC decreed in

the end that "the instant application for original registration is dismissed for lack of merit."

In its Motion for Reconsideration, City of Dumaguete contended that the dismissal of its

application was premature and tantamount to a denial of its right to due process. It has yet to

present evidence to prove factual matters in support of its application, such as the subject property

already being alienable and disposable at the time it was occupied and possessed. City of

Dumaguete also pointed out that its witness, Engr. Dorado, "testified only as to the physical status

of the land at the time when the cadastral survey of Dumaguete was made sometime in 1916." The

physical state of the subject property had already changed since 1916. It is now within the

"alienable and disposable area" as certified by the Bureau of Lands, as verified and certified by the

Land Management Sector, DENR Regional Office in Cebu City, who has yet to take the witness stand

before the RTC.

City of Dumaguete insisted that the RTC should continue with the hearing of LRC Case No.

N-201 and allow to present evidence to prove it is reclaimed land. It sufficiently alleged in its

application for registration that it has been in "open, continuous, exclusive, and notorious

possession of the [subject property] for more than thirty (30) years under a bona fide claim of

ownership."

PPA based its Opposition (To Applicants Motion for Reconsideration) on technical and

substantive grounds.

Page 5 of 350

Justice Teresita Leonardo-De Castro Cases (2008- Remedial Law

2015)

In its Order dated November 16, 2000, the RTC initially agreed with PPA that the Motion for

Reconsideration of City of Dumaguete violated Sections 4, 5, and 6, Rule 15 and Section 11, Rule 13

of the Rules of Court. Resultantly, the Motion for Reconsideration of petitioner was considered as

not filed and did not toll the running of the period to file an appeal, rendering final and executory

the order of dismissal of LRC Case No. N-201.

However, after taking into consideration the Supplemental Motion for Reconsideration of

City of Dumaguete, the RTC issued another Order dated December 7, 2000, setting aside its Order

dated September 7, 2000 in the interest of justice and resolving to have a full-blown proceeding to

determine factual issues in LRC Case No. N-201.

It was then the turn of PPA to file with the RTC a Motion for Reconsideration of the Order

dated December 7, 2000. In an Order dated February 20, 2001, the RTC denied the motion of PPA.

The Court wants to correct this error in its findings on the September 7, 2000 Order, that

Lot No. 1 is situated on the shoreline of Dumaguete City. The Court simply committed an oversight

on the City of Dumaguete's evidence that the lot is a foreshore land x x x when in fact it is not. And

it is for this reason that the court reconsidered and set aside said September 7, 2000 Order, to

correct the same while it is true that said September 7, 2000 Order had attained its finality, yet this

Court cannot in conscience allow injustice to perpetuate in this case and that hearing on the merits

must proceed to determine the legality and truthfulness of its application for registration of title.

The Court of Appeals found merit in the Petition of PPA and set aside the RTC Orders dated

December 7, 2000 and February 20, 2001.

Issue:

justice?

Can the court a quo allow the liberal application of the rules in order to avoid miscarriage of

Ruling:

Yes, the court may allow the liberal application of the rules.

The grant of a petition for certiorari under Rule 65 of the Rules of Court requires grave

abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction. Grave abuse of discretion exists

where an act is performed with a capricious or whimsical exercise of judgment equivalent to lack of

jurisdiction. The abuse of discretion must be patent and gross as to amount to an evasion of positive

duty or to a virtual refusal to perform a duty enjoined by law, or to act at all in contemplation of

law, as where the power is exercised in an arbitrary and despotic manner by reason of passion or

personal hostility.

The Court of Appeals erred in granting the writ of certiorari in favor of PPA. The RTC did not

commit grave abuse of discretion when, in its Orders dated December 7, 2000 and February 20,

2001, it set aside the order of dismissal of LRC Case No. N-201 and resolved to have a full-blown

proceeding to determine factual issues in said case.

Page 6 of 350

Justice Teresita Leonardo-De Castro Cases (2008- Remedial Law

2015)

Procedural rules were conceived to aid the attainment of justice. If a stringent application of

the rules would hinder rather than serve the demands of substantial justice, the former must yield

to the latter. In Basco v. Court of Appeals, we allowed a liberal application of technical rules of

procedure, pertaining to the requisites of a proper notice of hearing, upon consideration of the

importance of the subject matter of the controversy.

Likewise, in Samoso v. CA, the Court ruled:

But time and again, the Court has stressed that the rules of procedure are not to be applied

in a very strict and technical sense. The rules of procedure are used only to help secure not override

substantial justice. The right to appeal should not be lightly disregarded by a stringent application

of rules of procedure especially where the appeal is on its face meritorious and the interests of

substantial justice would be served by permitting the appeal.

In the case at bar, the Motion for Reconsideration and Supplemental Motion for

Reconsideration of City of Dumaguete , which sought the reversal of RTC Order dated September 7,

2000 dismissing LRC Case No. N-201, cite meritorious grounds that justify a liberal application of

procedural rules.

The dismissal by the RTC of LRC Case No. N-201 for lack of jurisdiction is patently

erroneous.

PPA sought the dismissal of LRC Case No. N-201 on the ground of lack of jurisdiction, not

because of the insufficiency of the allegations and prayer therein, but because the evidence

presented by petitioner itself during the trial supposedly showed that the subject property is a

foreshore land, which is not alienable and disposable. The RTC granted the Motion to Dismiss of

PPA in its Order dated September 7, 2000. The RTC went beyond the allegations and prayer for

relief in the Application for Original Registration of City of Dumaguete and already scrutinized and

weighed the testimony of Engr. Dorado, the only witness petitioner was able to present.

As to whether or not the subject property is indeed foreshore land is a factual issue which

the RTC should resolve in the exercise of its jurisdiction, after giving both parties the opportunity to

present their respective evidence at a full-blown trial.

It is true that City of Dumaguete, as the applicant, has the burden of proving that the subject

property is alienable and disposable and its title to the same is capable of registration. However, we

stress that the RTC, when it issued its Order dated September 7, 2000, had so far heard only the

testimony of Engr. Dorado, the first witness. City of Dumaguete was no longer afforded the

opportunity to present other witnesses and pieces of evidence in support of its Application. The

RTC Order dated September 7, 2000 already declaring the subject property as inalienable public

land, over which the RTC has no jurisdiction to order registration was evidently premature.

The RTC Order dated September 7, 2000 has not yet become final and executory as City of

Dumaguete was able to duly file a Motion for Reconsideration and Supplemental Motion for

Reconsideration of the same, which the RTC eventually granted in its Order dated December 7,

2000. Admittedly, said motions filed by City of Dumaguete did not comply with certain rules of

procedure. Ordinarily, such non-compliance would have rendered said motions as mere scraps of

Page 7 of 350

Justice Teresita Leonardo-De Castro Cases (2008- Remedial Law

2015)

paper, considered as not having been filed at all, and unable to toll the reglementary period for an

appeal. However, we find that the exceptional circumstances extant in the present case warrant the

liberal application of the rules.

In view of the foregoing circumstances, the RTC judiciously, rather than abusively or

arbitrarily, exercised its discretion when it subsequently issued the Order dated December 7, 2000,

setting aside its Order dated September 7, 2000 and proceeding with the trial in LRC Case No. N201.

JURISDICTION

EDDIE T. PANLILIO vs. COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS and LILIA G. PINEDA

G.R. No. 181478, July 15, 2009, J. Leonardo- De Castro

In cases where a COMELEC Division issues an interlocutory order, the same COMELEC Division

should resolve the motion for reconsideration of the order.

Facts:

The parties of the case were two of the contending gubernatorial candidates in the province

of Pampanga. On May 18, 2007, the Provincial Board of Canvassers of Pampanga proclaimed

Panlilio as the duly elected governor of Pampanga having garnered the highest number of votes. On

May 25, 2007, private respondent Pineda filed an election protest based on a number of grounds.

On July 23, 2007, the COMELEC, Second Division, issued the first assailed order giving due course to

private Pinedas election protest and directed among others, the revision of ballots pertaining to the

protested precincts of the Province of Pampanga. Panlilio filed a motion for reconsideration of the

aforesaid order but the same was denied. Aggrieved, petitioner filed the instant petition for

certiorari. Petitioner insists that the COMELEC En Banc gravely abused its discretion when it denied

his omnibus motion to certify his earlier motion for reconsideration and to stay the order directing

the collection of ballot boxes of the contested precincts in the province of Pampanga.

Issue:

Whether the COMELEC En Banc gravely abused its discretion when it denied Panlilios

omnibus motion to certify his motion for reconsideration.

Ruling:

No, it did not.

Since the COMELECs Division issued the interlocutory Order, the same COMELEC Division

should resolve the motion for reconsideration of the Order. The remedy of the aggrieved party is

neither to file a motion for reconsideration for certification to the COMELEC En Banc nor to elevate

the issue to the Court via a petition for certiorari. Under the Rules, the acts of a Division that are

subject of a motion for reconsideration must have a character of finality before the same can be

elevated to the COMELEC en banc. The elementary rule is that an order is final in nature if it

completely disposes of the entire case. But if there is something more to be done in the case after its

Page 8 of 350

Justice Teresita Leonardo-De Castro Cases (2008- Remedial Law

2015)

issuance, that order is interlocutory. Only final orders of the COMELEC in Division may be raised

before the COMELEC en banc. Furthermore, the present controversy does not fall under any of the

instances of which the COMELEC En Banc can take cognizance. Neither is it one where a Division is

not authorized to act nor one where the members of the Second Division have unanimously voted

to refer the issue to the COMELEC En Banc. Thus, the COMELEC En Banc is not the proper forum

where petitioner may bring the assailed interlocutory Orders for resolution.

CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION vs. FATIMA A. MACUD

G.R. No. 177531, September 10, 2009, J. Leonardo-De Castro

As a general rule, the defense of lack of jurisdiction may be raised at any stage of the

proceeding. However, it admits an exception where the party fully participated in the proceedings. A

teacher cannot raise want of jurisdiction when she has availed of the remedies in the proceedings.

Facts:

As a requirement for her appointment as Teacher I of the Department of Education, Fatima

A. Macud submitted her Personal Data Sheet (PDS) to the CSC Regional Office and declared that she

successfully passed the Professional Board Examination for Teachers (PBET). Upon investigation,

petitioner was formally charged with Dishonesty, Grave Misconduct and Conduct Prejudicial to the

Best Interest of the Service due to several irregularities in her Application Form (AF) and PDS such

as, first, disparity in Macuds date of birth as December 15, 1958 appeared as her date of birth in the

AF while it was December 15, 1965 that appeared in her PDS; second, the facial features of Macud

in the picture attached to her PDS vis--vis her features as shown in the picture attached to the AF

showed an obvious dissemblance; and lastly, the signature of Macud as appearing in her PDS is

likewise different from that affixed in her AF.

Macud asserted that she personally took the PBET and vehemently denied the findings

about the photograph alleging that the dissemblance of her picture attached to her AF and PSP from

her picture pasted on her PDS was because the two pictures were taken roughly nine (9) years

apart from each other. Anent the disparity in her signatures, petitioner reasoned out that it was the

result of the change of her status, i.e., she eventually got married and had to use the surname of her

husband. With respect to her date of birth, she alleged that her known and recognized date of birth

prior and up to 1994 was 15 December 1958. Thereafter, she was informed that her correct date of

birth was 15 December 1965.

CSC Regional Office found Macud guilty of dishonesty. She appealed to CSC Central Office

but the same was denied. Macud elevated the matter to the CA which reversed the decision of

CSCRO and CSCCO on the ground of lack jurisdiction. The CA held that CSC had no jurisdiction over

the case because it is the Magna Carta for Public School Teachers which should apply thus

Department of Education, Culture and Sports (DECS) shall have jurisdiction. Hence, the present

petition.

Issue:

Whether or not CSC has jurisdiction over the case of Macud

Ruling:

Page 9 of 350

Justice Teresita Leonardo-De Castro Cases (2008- Remedial Law

2015)

Yes. We grant the petition.

As the Solicitor General correctly argues, petitioner CSC is the constitutional body charged

with the establishment and administration of a career civil service which embraces all branches

and agencies of the government.

Article IX-B, Section 2(1) of the 1987 Constitution provides:

Section 2. (1) The civil service embraces all branches, subdivisions,

instrumentalities, and agencies of the Government, including government-owned or

controlled corporations with original charters. x x x (emphasis ours)

Section 3 of the same Article further states:

Section 3. The Civil Service Commission, as the central personnel agency of the

Government, shall establish a career service and adopt measures to promote morale,

efficiency, integrity, responsiveness, progressiveness, and courtesy in the civil service. It

shall strengthen the merit and rewards system, integrate all human resources development

programs for all levels and ranks, and institutionalize a management climate conducive to

public accountability. It shall submit to the President and the Congress an annual report on

its personnel programs. (emphasis ours)

In the recent case of Civil Service Commission v. Alfonso, the Court held that special laws such

as R.A. 4670 did not divest the CSC of its inherent power to supervise and discipline all members of

the civil service, including public school teachers. To quote from that decision:

As the central personnel agency of the government, the CSC has jurisdiction to

supervise the performance of and discipline, if need be, all government employees,

including those employed in government-owned or controlled corporations with original

charters such as PUP. Accordingly, all PUP officers and employees, whether they be

classified as teachers or professors pursuant to certain provisions of law, are deemed, first

and foremost, civil servants accountable to the people and answerable to the CSC in cases of

complaints lodged by a citizen against them as public servants. xxx

xxx xxx xxx

We are not unmindful of certain special laws that allow the creation of disciplinary

committees and governing bodies in different branches, subdivisions, agencies and

instrumentalities of the government to hear and decide administrative complaints against

their respective officers and employees. Be that as it may, we cannot interpret the creation

of such bodies nor the passage of laws such as R.A. Nos. 8292 and 4670 allowing for the

creation of such disciplinary bodies as having divested the CSC of its inherent power to

supervise and discipline government employees, including those in the academe. To hold

otherwise would not only negate the very purpose for which the CSC was established, i.e. to

instill professionalism, integrity, and accountability in our civil service, but would also

impliedly amend the Constitution itself. (emphasis supplied)

Page 10 of 350

Justice Teresita Leonardo-De Castro Cases (2008- Remedial Law

2015)

This Court has also previously held in Civil Service Commission v. Albao that the CSC has the

authority to directly institute proceedings to discipline a government employee in order to protect

the integrity of the civil service.

Indeed, where an administrative case involves the alleged fraudulent procurement of an

eligibility or qualification for employment in the civil service, it is but proper that the CSC would

have jurisdiction over the case for it is in the best position to determine if there has been a violation

of civil service rules and regulations.

Moreover, it is now too late for respondent to challenge the jurisdiction of the CSC. After

participating in the proceedings before the CSC, respondent is effectively barred by estoppel from

challenging the CSCs jurisdiction. While it is a rule that a jurisdictional question may be raised

anytime, this, however, admits of an exception where, as in this case, estoppel has supervened.

DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS and BANGKO SENTRAL NG PILIPINAS vs. HON. FRANCO

T. FALCON, IN HIS CAPACITY AS THE PRESIDING JUDGE OF BRANCH 71 OF THE REGIONAL

TRIAL COURT IN PASIG CITY and BCA INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION

G.R. No. 176657, September 1, 2010, J. Leonardo-De Castro

Court has full discretionary power to take cognizance and assume jurisdiction of special civil

actions for certiorari and mandamus filed directly with it for exceptionally compelling reasons or if

warranted by the nature of the issues clearly and specifically raised in the petition. The Court may

suspend or even disregard rules when the demands of justice so require.

No court, aside from the Supreme Court, may enjoin a national government project unless

the matter is one of extreme urgency involving a constitutional issue such that unless the act

complained of is enjoined, grave injustice or irreparable injury would arise.

Facts:

In line with the DFAs mandate to improve the passport and visa issuance system, as well as

the storage and retrieval of its related application records, and pursuant to our governments ICAO

commitments, the DFA secured the approval of the President of the Philippines, as Chairman of the

Board of the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA), for the implementation of the

Machine Readable Passport and Visa Project (the MRP/V Project) under the Build-Operate-andTransfer (BOT) scheme, provided for by Republic Act No. 6957, as amended by Republic Act No.

7718 (the BOT Law), and its Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRR). There were several

bidders responded and BCA was among those that pre-qualified and submitted its technical and

financial proposals. PBAC found BCAs bid to be the sole complying bid; hence, it permitted the DFA

to engage in direct negotiations with BCA. On even date, the PBAC recommended to the DFA

Secretary the award of the MRP/V Project to BCA on a BOT arrangement. BCA incorporated a

project company, the Philippine Passport Corporation (PPC) to undertake and implement the

MRP/V Project.

A Build-Operate-Transfer Agreement (BOT Agreement) between the DFA and PPC was

signed by DFA Acting Secretary Lauro L. Baja, Jr. and PPC President Bonifacio Sumbilla. Former

DFA Secretary Teofisto Guingona and Bonifacio Sumbilla, this time as BCA President, signed an

Amended BOT Agreement in order to reflect the change in the designation of the parties and to

Page 11 of 350

Justice Teresita Leonardo-De Castro Cases (2008- Remedial Law

2015)

harmonize Section 11.3 with Section 11.8 of the IRR of the BOT Law. The Amended BOT Agreement

was entered into by the DFA and BCA with the conformity of PPC.

An Assignment Agreement was executed by BCA and PPC, whereby BCA assigned and ceded

its rights, title, interest and benefits arising from the Amended BOT Agreement to PPC. As set out in

Article 8 of the original and the Amended BOT Agreement, the MRP/V Project was divided into six

phases. Both the DFA and BCA impute breach of the Amended BOT Agreement against each other.

According to the DFA, delays in the completion of the phases permeated the MRP/V Project

due to the submission of deficient documents as well as intervening issues regarding BCA/PPCs

supposed financial incapacity to fully implement the project. On the other hand, BCA contends that

the DFA failed to perform its reciprocal obligation to issue to BCA a Certificate of Acceptance of

Phase 1 within 14 working days of operation purportedly required by Section 14.04 of the

Amended BOT Agreement.

Later, the DFA sought the opinion of the Department of Finance (DOF) and the Department

of Justice (DOJ) regarding the appropriate legal actions in connection with BCAs alleged delays in

the completion of the MRP/V Project. BCA, in turn, submitted various letters and documents to

prove its financial capability to complete the MRP/V Project. However, the DFA claimed these

documents were unsatisfactory or of dubious authenticity. DFA sent a Notice of Termination to BCA

and PPC due to their alleged failure to submit proof of financial capability to complete the entire

MRP/V Project in accordance with the financial warranty under Section 5.02(A) of the Amended

BOT Agreement.

PDRCI invited the DFA to submit its Answer to the Request for Arbitration within 30 days

from receipt of said letter and also requested both the DFA and BCA to nominate their chosen

arbitrator within the same period of time. Initially, the DFA requested for an extension of time to

file its answer, without prejudice to jurisdictional and other defenses and objections available to it

under the law. However, DFA declined the request for arbitration before the PDRCI. While it

expressed its willingness to resort to arbitration, the DFA pointed out that under Section 19.02 of

the Amended BOT Agreement, there is no mention of a specific body or institution that was

previously authorized by the parties to settle their dispute. DOJ concurred with the steps taken by

the DFA, stating that there was basis in law and in fact for the termination of the MRP/V Project.

Thereafter, the DFA and the BSP entered into a Memorandum of Agreement for the latter to

provide the former passports compliant with international standards. The BSP then solicited bids

for the supply, delivery, installation and commissioning of a system for the production of Electronic

Passport Booklets or e-Passports. For BCA, the BSPs invitation to bid for the supply and purchase of

e-Passports (the e-Passport Project) would only further delay the arbitration it requested from the

DFA. Moreover, this new e-Passport Project by the BSP and the DFA would render BCAs remedies

moot inasmuch as the e-Passport Project would then be replacing the MRP/V Project which BCA

was carrying out for the DFA.

Thereafter, BCA filed an application for preliminary injunction. The trial court issued an

Order granting BCAs application for preliminary injunction. Thereafter, DFA and the BSP filed the

instant Petition for Certiorari and prohibition under Rule 65 of the Rules of Court with a prayer for

the issuance of a temporary restraining order and/or a writ of preliminary injunction, imputing

grave abuse of discretion on the trial court when it granted interim relief to BCA .

Page 12 of 350

Justice Teresita Leonardo-De Castro Cases (2008- Remedial Law

2015)

Issue:

1. Whether or not petitioners did not follow the hierarchy of courts by filing their petition

directly with this Court, without filing a motion for reconsideration with the RTC and

without filing a petition first with the Court of Appeals.

2. Whether or not the trial court had jurisdiction to issue a writ of preliminary injunction

in the present case

Ruling:

1. Although the direct filing of petitions for certiorari with the Supreme Court is discouraged when

litigants may still resort to remedies with the lower courts, we have in the past overlooked the

failure of a party to strictly adhere to the hierarchy of courts on highly meritorious

grounds. Most recently, the Court relaxed the rule on court hierarchy in the case of Roque, Jr. v.

Commission on Elections wherein it ruled that the policy on the hierarchy of courts, which

petitioners indeed failed to observe, is not an iron-clad rule. For indeed the Court has full

discretionary power to take cognizance and assume jurisdiction of special civil actions

for certiorari and mandamus filed directly with it for exceptionally compelling reasons or if

warranted by the nature of the issues clearly and specifically raised in the petition.

The Court deems it proper to adopt a similarly liberal attitude in the present case in

consideration of the transcendental importance of an issue raised herein. This is the first time that

the Court is confronted with the question of whether an information and communication

technology project, which does not conform to our traditional notion of the term infrastructure, is

covered by the prohibition on the issuance of court injunctions found in Republic Act No. 8975,

which is entitled An Act to Ensure the Expeditious Implementation and Completion of Government

Infrastructure Projects by Prohibiting Lower Courts from Issuing Temporary Restraining Orders,

Preliminary Injunctions or Preliminary Mandatory Injunctions, Providing Penalties for Violations

Thereof, and for Other Purposes. Taking into account the current trend of computerization and

modernization of administrative and service systems of government offices, departments and

agencies, the resolution of this issue for the guidance of the bench and bar, as well as the general

public, is both timely and imperative.

2. Yes. The trial court had jurisdiction to issue a writ of preliminary injunction against the ePassport Project.

It is indubitable that no court, aside from the Supreme Court, may enjoin a national

government project unless the matter is one of extreme urgency involving a constitutional issue

such that unless the act complained of is enjoined, grave injustice or irreparable injury would arise.

Under Section 2(a) of Republic Act No. 8975, there are three types of national government projects

enumerated in Section 2(a), to wit:

(a)

(b)

(c)

current and future national government infrastructure projects, engineering

works and service contracts, including projects undertaken by governmentowned and controlled corporations;

all projects covered by R.A. No. 6975, as amended by R.A. No. 7718, or the

Build-Operate-and-Transfer ( BOT) Law; and

other related and necessary activities, such as site acquisition, supply and/or

installation of equipment and materials, implementation, construction,

Page 13 of 350

Justice Teresita Leonardo-De Castro Cases (2008- Remedial Law

2015)

completion, operation, maintenance, improvement repair and rehabilitation,

regardless of the source of funding.

Although the Court finds that the trial court had jurisdiction to issue the writ of preliminary

injunction, we cannot uphold the theory of BCA and the trial court that the definition of the term

infrastructure project in Republic Act No. 9184 should be applied to the BOT Law.

Republic Act No. 9285 is a general law applicable to all matters and controversies to be

resolved through alternative dispute resolution methods. This law allows a Regional Trial Court to

grant interim or provisional relief, including preliminary injunction, to parties in an arbitration case

prior to the constitution of the arbitral tribunal. This general statute, however, must give way to a

special law governing national government projects, Republic Act No. 8975 which prohibits courts,

except the Supreme Court, from issuing TROs and writs of preliminary injunction in cases involving

national government projects.

However, as discussed above, the prohibition in Republic Act No. 8975 is inoperative in this

case, since petitioners failed to prove that the e-Passport Project is national government project as

defined therein. Thus, the trial court had jurisdiction to issue a writ of preliminary injunction

against the e-Passport Project.

BF HOMES, INC. and THE PHILIPPINE WATERWORKS AND CONSTRUCTION CORP.

vs. MANILA ELECTRIC COMPANY

G.R. No. 171624, December 6, 2010, J. Leonardo-De Castro

Administrative agencies, like the Energy Regulatory Commission, are tribunals of limited

jurisdiction and, as such, could wield only such as are specifically granted to them by the enabling

statutes. In relation thereto is the doctrine of primary jurisdiction involving matters that demand the

special competence of administrative agencies even if the question involved is also judicial in nature.

Facts:

MERALCO is a corporation duly organized and existing under Philippine laws engaged in

the distribution and sale of electric power in Metro Manila. On the other hand, BF Homes and PWCC

are owners and operators of waterworks systems delivering water to over 12,000 households and

commercial buildings in BF Homes subdivisions in Paranaque City, Las Pinas City, Caloocan City,

and Quezon City. The water distributed in the waterworks systems owned and operated by BF

Homes and PWCC is drawn from deep wells using pumps run by electricity supplied by MERALCO.

BF Homes and PWCC filed a Petition [With Prayer for the Issuance of Writ of Preliminary

Injunction and for the Immediate Issuance of Restraining Order] against MERALCO docketed as

Civil Case No. 03-0151, which the RTC granted. The Motion for Reconsideration of MERALCO was

denied by the RTC.

Aggrieved, MERALCO filed with the Court of Appeals a Petition for Certiorari under Rule 65

of the Rules of Court. MERALCO sought the reversal of the RTC Orders granting a writ of

preliminary injunction in favor of BF Homes and PWCC. MERALCO asserted that the RTC had no

jurisdiction over the application of BF Homes and PWCC for issuance of such a writ. In its Decision,

the Court of Appeals agreed with MERALCO that the RTC had no jurisdiction to issue a writ of

Page 14 of 350

Justice Teresita Leonardo-De Castro Cases (2008- Remedial Law

2015)

preliminary injunction in Civil Case No. 03-0151, as said trial court had no jurisdiction over the

subject matter of the case to begin with. In a Resolution, the Court of Appeals denied the Motion for

Reconsideration of BF Homes and PWCC.

Now, BF Homes and PWCC come before this Court via the instant Petition. BF Homes and

PWCC argued that due to the threat of MERALCO to disconnect electric services, BF Homes and

PWCC had no other recourse but to seek an injunctive remedy from the RTC under its general

jurisdiction. The merits of Civil Case No. 03-0151 was not yet in issue, only the propriety of issuing

a writ of preliminary injunction to prevent an irreparable injury. Even granting that the RTC has no

jurisdiction over the subject matter of Civil Case No. 03-0151, the ERC by enabling law has no

injunctive power to prevent the disconnection by MERALCO of electric services to BF Homes and

PWCC.

Issue:

Whether the jurisdiction over the subject matter of Civil Case No. 03-0151 lies with the RTC

or the Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC).

Ruling:

A careful review of the material allegations of BF Homes and PWCC in their Petition before

the RTC reveals that the very subject matter thereof is the off-setting of the amount of refund they

are supposed to receive from MERALCO against the electric bills they are to pay to the same

company. This is squarely within the primary jurisdiction of the ERC.

The right of BF Homes and PWCC to refund, on which their claim for off-setting depends,

originated from the MERALCO Refund cases. In said cases, the Court (1) authorized MERALCO to

adopt a rate adjustment in the amount of P0.017 per kilowatthour, effective with respect to its

billing cycles beginning February 1994; and (2) ordered MERALCO to refund to its customers or

credit in said customers favor for future consumption P0.167 per kilowatthour, starting with the

customers billing cycles that begin February 1998, in accordance with the ERB Decision dated

February 16, 1998.

It bears to stress that in the MERALCO Refund cases, this Court only affirmed the February

16, 1998 Decision of the ERB (predecessor of the ERC) fixing the just and reasonable rate for the

electric services of MERALCO and granting refund to MERALCO consumers of the amount they

overpaid. Said Decision was rendered by the ERB in the exercise of its jurisdiction to determine and

fix the just and reasonable rate of power utilities such as MERALCO.

Presently, the ERC has original and exclusive jurisdiction under Rule 43(u) of the EPIRA

over all cases contesting rates, fees, fines, and penalties imposed by the ERC in the exercise of its

powers, functions and responsibilities, and over all cases involving disputes between and among

participants or players in the energy sector. Section 4(o) of the EPIRA Implementing Rules and

Regulation provides that the ERC shall also be empowered to issue such other rules that are

essential in the discharge of its functions as in independent quasi-judicial body.

Indubitably, the ERC is the regulatory agency of the government having the authority and

supervision over MERALCO.Thus, the task to approve the guidelines, schedules, and details of the

Page 15 of 350

Justice Teresita Leonardo-De Castro Cases (2008- Remedial Law

2015)

refund by MERALCO to its consumers, to implement the judgment of this Court in the MERALCO

Refund cases, also falls upon the ERC. By filing their Petition before the RTC, BF Homes and PWCC

intend to collect their refund without submitting to the approved schedule of the ERC, and in effect,

enjoy preferential right over the other equally situated MERALCO consumers.

Administrative agencies, like the ERC, are tribunals of limited jurisdiction and, as such,

could wield only such as are specifically granted to them by the enabling statutes. In relation

thereto is the doctrine of primary jurisdiction involving matters that demand the special

competence of administrative agencies even if the question involved is also judicial in

nature. Courts cannot and will not resolve a controversy involving a question within the jurisdiction

of an administrative tribunal, especially when the question demands the sound exercise of

administrative discretion requiring special knowledge, experience and services of the

administrative tribunal to determine technical and intricate matters of fact. The court cannot

arrogate into itself the authority to resolve a controversy, the jurisdiction of which is initially

lodged with the administrative body of special competence.

Since the RTC had no jurisdiction over the Petition of BF Homes and PWCC in Civil Case No.

03-0151, then it was also devoid of any authority to act on the application of BF Homes and PWCC

for the issuance of a writ of preliminary injunction contained in the same Petition. The ancillary and

provisional remedy of preliminary injunction cannot exist except only as an incident of an

independent action or proceeding

Lastly, the Court herein already declared that the RTC not only lacked the jurisdiction to

issue the writ of preliminary injunction against MERALCO, but that the RTC actually had no

jurisdiction at all over the subject matter of the Petition of BF Homes and PWCC in Civil Case No. 030151. Therefore, in addition to the dissolution of the writ of preliminary injunction issued by the

RTC, the Court also deems it appropriate to already order the dismissal of the Petition of BF Homes

and PWCC in Civil Case No. 03-0151 for lack of jurisdiction of the RTC over the subject matter of the

same.

BERNABE L. NAVIDA et al. vs. HON. TEODORO A. DIZON, JR.

G.R. No. 125078, May 30, 2011, J. Leonardo-De Castro

The rule is settled that jurisdiction over the subject matter of a case is conferred by law and is

determined by the allegations in the complaint and the character of the relief sought, irrespective of

whether the plaintiffs are entitled to all or some of the claims asserted therein. Once vested by law, on

a particular court or body, the jurisdiction over the subject matter or nature of the action cannot be

dislodged by anybody other than by the legislature through the enactment of a law.

Facts:

Before the Court are consolidated Petitions for Review on Certiorari under Rule 45 of the

Rules of Court, which arose out of two civil cases that were filed in different courts but whose

factual background and issues are closely intertwined.

Beginning 1993, a number of personal injury suits were filed in different Texas state courts

by citizens of twelve foreign countries, including the Philippines. The thousands of plaintiffs sought

damages for injuries they allegedly sustained from their exposure to dibromochloropropane

Page 16 of 350

Justice Teresita Leonardo-De Castro Cases (2008- Remedial Law

2015)

(DBCP), a chemical used to kill nematodes (worms), while working on farms in 23 foreign

countries. The cases were eventually transferred to, and consolidated in, the Federal District Court

for the Southern District of Texas, Houston Division. The defendants in the consolidated cases

prayed for the dismissal of all the actions under the doctrine of forum non conveniens.

In a Memorandum and Order dated July 11, 1995, the Federal District Court conditionally

granted the defendants motion to dismiss. Notwithstanding the dismissal of the consolidated cases,

the Court noted that in the event that the highest court of any foreign country finally affirms the

dismissal for lack of jurisdiction of an action commenced by a plaintiff in these actions in his home

country or the country in which he was injured, that plaintiff may return to this court and, upon

proper motion, the court will resume jurisdiction over the action as if the case had never been

dismissed for [forum non conveniens].

In accordance with the above Memorandum and Order, a total of 336 plaintiffs from General

Santos City (the petitioners in G.R. No. 125078, hereinafter referred to as NAVIDA, et al.) filed a

Joint Complaint in the RTC of General Santos City. Navida, et al., prayed for the payment of damages

in view of the illnesses and injuries to the reproductive systems which they allegedly suffered

because of their exposure to DBCP. They claimed, among others, that they were exposed to this

chemical when they used the same in the banana plantations where they worked at; and/or when

they resided within the agricultural area where such chemical was used. Navida, et al., claimed that

their illnesses and injuries were due to the fault or negligence of each of the defendant companies

in that they produced, sold and/or otherwise put into the stream of commerce DBCP-containing

products. According to NAVIDA, et al., they were allowed to be exposed to the said products, which

the defendant companies knew, or ought to have known, were highly injurious to the formers

health and well-being.

Instead of answering the complaint, most of the defendant companies respectively filed

their Motions for Bill of Particulars.

Without resolving the motions filed by the parties, the RTC of General Santos City issued an

Order dismissing the complaint. First, the trial court determined that it did not have jurisdiction to

hear the case. It held that the subject matter stated in the complaint consisted of activity engaged in

by foreign defendants outside Philippine territory, hence, outside and beyond the jurisdiction of

Philippine Courts. It further held that Navida, et al. did not freely choose to file the complaint, but

were coerced to do so, merely to comply with the U.S. District Courts Order dated July 11, 1995,

and in order for them to have the opportunity to return to the U.S. District Court.

Thereafter, another joint complaint for damages against the same defendants was filed

before the RTC of Davao City by 155 plaintiffs from Davao City. These plaintiffs (the petitioners in

G.R. No. 126654, hereinafter referred to as ABELLA, et al.) in their complaint, pray for the same

reliefs as those mentioned in the complaint filed by Navida, et al. They likewise based their claims

on almost the same facts as those alleged by Navida, et al.

Finding that it has no jurisdiction over the case the RTC of Davao City dismissed the

complaint of Abella, et al.

Issue/s:

Page 17 of 350

Justice Teresita Leonardo-De Castro Cases (2008- Remedial Law

2015)

1. Whether or not the RTC of General Santos City and the RTC of Davao City erred in

dismissing the Complaints of herein petitioners for lack of jurisdiction.

2. Whether or not the RTC of General Santos City and the RTC of Davao City validly acquired

jurisdiction over the persons of all the defendant companies

Ruling:

1. Yes, General Santos City and the RTC of Davao City erred in dismissing the Complaints of herein

petitioners for lack of jurisdiction.

The rule is settled that jurisdiction over the subject matter of a case is conferred by law and

is determined by the allegations in the complaint and the character of the relief sought, irrespective

of whether the plaintiffs are entitled to all or some of the claims asserted therein. Once vested by

law, on a particular court or body, the jurisdiction over the subject matter or nature of the action

cannot be dislodged by anybody other than by the legislature through the enactment of a law.

At the time of the filing of the complaints, the jurisdiction of the RTC in civil cases under

Batas Pambansa Blg. 129, as amended by Republic Act No. 7691, was:

SEC. 19. Jurisdiction in civil cases. Regional Trial Courts shall exercise exclusive original

jurisdiction:

xxxx

(8) In all other cases in which the demand, exclusive of interest, damages of whatever kind,

attorneys fees, litigation expenses, and costs or the value of the property in controversy

exceeds One hundred thousand pesos (P100,000.00) or, in such other cases in Metro

Manila, where the demand, exclusive of the abovementioned items exceeds Two hundred

thousand pesos (P200,000.00).

As specifically enumerated in the amended complaints, NAVIDA, et al., and ABELLA, et al.,

point to the acts and/or omissions of the defendant companies in manufacturing, producing, selling,

using, and/or otherwise putting into the stream of commerce, nematocides which contain DBCP,

"without informing the users of its hazardous effects on health and/or without instructions on its

proper use and application."

Verily, in Citibank, N.A. v. Court of Appeals, this Court has always reminded that jurisdiction

of the court over the subject matter of the action is determined by the allegations of the complaint,

irrespective of whether or not the plaintiffs are entitled to recover upon all or some of the claims

asserted therein. The jurisdiction of the court cannot be made to depend upon the defenses set up

in the answer or upon the motion to dismiss, for otherwise, the question of jurisdiction would

almost entirely depend upon the defendants. What determines the jurisdiction of the court is the

nature of the action pleaded as appearing from the allegations in the complaint. The averments

therein and the character of the relief sought are the ones to be consulted.

Clearly then, the acts and/or omissions attributed to the defendant companies constitute a

quasi-delict which is the basis for the claim for damages filed by NAVIDA, et al., and ABELLA, et al.,

with individual claims of approximately P2.7 million for each plaintiff claimant, which obviously

falls within the purview of the civil action jurisdiction of the RTCs.

Page 18 of 350

Justice Teresita Leonardo-De Castro Cases (2008- Remedial Law

2015)

Moreover, the injuries and illnesses, which NAVIDA, et al., and ABELLA, et al., allegedly

suffered resulted from their exposure to DBCP while they were employed in the banana plantations

located in the Philippines or while they were residing within the agricultural areas also located in

the Philippines. The factual allegations in the Amended Joint-Complaints all point to their cause of

action, which undeniably occurred in the Philippines. The RTC of General Santos City and the RTC of

Davao City obviously have reasonable basis to assume jurisdiction over the cases.

It is, therefore, error on the part of the courts a quo when they dismissed the cases on the

ground of lack of jurisdiction on the mistaken assumption that the cause of action narrated by

NAVIDA, et al., and ABELLA, et al., took place abroad and had occurred outside and beyond the

territorial boundaries of the Philippines, i.e., "the manufacture of the pesticides, their packaging in

containers, their distribution through sale or other disposition, resulting in their becoming part of

the stream of commerce," and, hence, outside the jurisdiction of the RTCs.

Certainly, the cases below are not criminal cases where territoriality, or the situs of the act

complained of, would be determinative of jurisdiction and venue for trial of cases. In personal civil

actions, such as claims for payment of damages, the Rules of Court allow the action to be

commenced and tried in the appropriate court, where any of the plaintiffs or defendants resides, or

in the case of a non-resident defendant, where he may be found, at the election of the plaintiff.

2. Yes, the RTC of General Santos City and the RTC of Davao City validly acquired jurisdiction over

the persons of all the defendant companies.

Rule 14, Section 20 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure provides that "[t]he defendants

voluntary appearance in the action shall be equivalent to service of summons." In this connection,

all the defendant companies designated and authorized representatives to receive summons and to

represent them in the proceedings before the courts a quo. All the defendant companies submitted

themselves to the jurisdiction of the courts a quo by making several voluntary appearances, by

praying for various affirmative reliefs, and by actively participating during the course of the

proceedings below.

In line herewith, this Court, in Meat Packing Corporation of the Philippines v.

Sandiganbayan, held that jurisdiction over the person of the defendant in civil cases is acquired

either by his voluntary appearance in court and his submission to its authority or by service of

summons. Furthermore, the active participation of a party in the proceedings is tantamount to an

invocation of the courts jurisdiction and a willingness to abide by the resolution of the case, and

will bar said party from later on impugning the court or bodys jurisdiction.

Thus, the RTC of General Santos City and the RTC of Davao City have validly acquired

jurisdiction over the persons of the defendant companies, as well as over the subject matter of the

instant case. What is more, this jurisdiction, which has been acquired and has been vested on the

courts a quo, continues until the termination of the proceedings.

It may also be pertinently stressed that "jurisdiction" is different from the "exercise of

jurisdiction." Jurisdiction refers to the authority to decide a case, not the orders or the decision

rendered therein. Accordingly, where a court has jurisdiction over the persons of the defendants

and the subject matter, as in the case of the courts a quo, the decision on all questions arising

therefrom is but an exercise of such jurisdiction. Any error that the court may commit in the

Page 19 of 350

Justice Teresita Leonardo-De Castro Cases (2008- Remedial Law

2015)

exercise of its jurisdiction is merely an error of judgment, which does not affect its authority to

decide the case, much less divest the court of the jurisdiction over the case.

NM ROTHSCHILD & SONS (AUSTRALIA) LIMITED vs. LEPANTO CONSOLIDATED MINING

COMPANY

G.R. No. 175799, November 28, 2011, J. Leonardo-De Castro

A party cannot invoke the jurisdiction of a court to secure affirmative relief against his

opponent and after obtaining or failing to obtain such relief, repudiate or question that same

jurisdiction.

Facts:

Lepanto Consolidated Mining Company (Lepanto) filed with the RTC of Makati City a

Complaint against NM Rothschild & Sons (Australia) Limited praying for a judgment declaring the

loan and hedging contracts between the parties void for being contrary to Article 2018 of the Civil

Code of the Philippines and for damages.

Upon Lepantos motion, the trial court authorized Lepantos counsel to personally bring the

summons and Complaint to the Philippine Consulate General in Sydney, Australia for the latter

office to effect service of summons on NM Rothschild & Sons. NM Rothschild & Sons filed a Special

Appearance With Motion to Dismiss praying for the dismissal of the Complaint on the ground that

the court has not acquired jurisdiction over the person of NM Rothschild & Sons due to the

defective and improper service of summons.

Later, NM Rothschild & Sons filed two Motions: (1) a Motion for Leave to take the

deposition of Mr. Paul Murray (Director, Risk Management of NM Rothschild & Sons) before the

Philippine Consul General; and (2) a Motion for Leave to Serve Interrogatories on Lepanto.

The RTC denied the Motion to Dismiss. According to the trial court, there was a proper service of

summons through the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA). The CA affirmed the decision of the

RTC. Meanwhile, the RTC issued an Order directing Lepanto to answer some of the questions in NM

Rothschild & Sonss Interrogatories to Lepanto.

Lepanto vigorously argues that NM Rothschild & Sons should be held to have voluntarily

appeared before the trial court when it prayed for, and was actually afforded, specific reliefs from

the trial court. Lepanto points out that while NM Rothschild & Sonss Motion to Dismiss was still

pending, it prayed for and was able to avail of modes of discovery against Lepanto, such as written

interrogatories, requests for admission, deposition, and motions for production of documents.

NM Rothschild & Sons counters that in the leading case of La Naval Drug Corporation v.

Court of Appeals, a party may file a Motion to Dismiss on the ground of lack of jurisdiction over its

person, and at the same time raise affirmative defenses and pray for affirmative relief, without

waiving its objection to the acquisition of jurisdiction over its person.

Issue:

Is NM Rothschild & Sons deemed to have voluntarily submitted to the jurisdiction of the

court by seeking affirmative reliefs?

Page 20 of 350

Justice Teresita Leonardo-De Castro Cases (2008- Remedial Law

2015)

Ruling:

Yes, NM Rothschild & Sons, by seeking affirmative reliefs from the trial court, is deemed to

have voluntarily submitted to the jurisdiction of said court.

NM Rothschild & Sons misunderstood the ruling in La Naval. A close reading of La Naval

reveals that the SC intended a distinction between the raising of affirmative defenses in an Answer

(which would not amount to acceptance of the jurisdiction of the court) and the prayer for

affirmative reliefs (which would be considered acquiescence to the jurisdiction of the court).

The Rules of Court merely mentions other grounds in a Motion to Dismiss aside from lack of

jurisdiction over the person of the defendant. This clearly refers to affirmative defenses, rather than

affirmative reliefs.

Thus, while mindful of its ruling in La Naval, in several cases, ruled that seeking affirmative

relief in a court is tantamount to voluntary appearance therein.

NM Rothschild & Sons, by seeking affirmative reliefs from the trial court, is deemed to have

voluntarily submitted to the jurisdiction of said court. A party cannot invoke the jurisdiction of a

court to secure affirmative relief against his opponent and after obtaining or failing to obtain such

relief, repudiate or question that same jurisdiction.

Consequently, the trial court cannot be considered to have committed grave abuse of

discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction in the denial of the Motion to Dismiss on

account of failure to acquire jurisdiction over the person of NM Rothschild & Sons.

PHILIPPINE LONG DISTANCE TELEPHONE COMPANY vs.

EASTERN TELECOMMUNICATIONS PHILIPPINES, INC

G.R. No. 163037, February 6, 2013, J. Leonardo-De Castro

It is a rule of universal application, almost, that courts of justice constituted to pass upon

substantial rights will not consider questions in which no actual interests are involved; they decline

jurisdiction of moot cases. And where the issue has become moot and academic, there is no justiciable

controversy, so that a declaration thereon would be of no practical use or value. There is no actual

substantial relief to which petitioners would be entitled and which would be negated by the dismissal

of the petition

Facts:

Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Makati City rendered a decision approving the Compromise

Agreement submitted by PLDT and respondent Eastern Telecommunications Philippines, Inc.

(ETPI) Among others stated therein, PLDT guarantees that all the outgoing telephone traffic to

Hongkong destined to ETPIs correspondent therein, Cable & Wireless Hongkong Ltd., its successors

and assigns, shall be coursed by PLDT through the ETPI provided circuits and facilities between the

Philippines and Hongkong, that neither party shall use or threaten to use its gateway or any other

facilities to subvert the purposes of the Agreement and it shall take effect and shall continue in

Page 21 of 350

Justice Teresita Leonardo-De Castro Cases (2008- Remedial Law

2015)

effect until November 28, 2003, provided that a written notice of termination is given by one party

to the other not later than November 28, 2001. In the absence of such written notice, the Agreement

shall continue in effect beyond November 28, 2003 but may be terminated thereafter by either

party by giving to the other a prior two year written notice of termination, and that in the event of

breach, the parties may obtain judicial relief, including a writ of execution.

Thereafter, ETPI filed a Motion for Enforcement/Execution and an Urgent Motion in RTC,

alleging, among others, that PLDT violated the terms of the above Compromise Agreement. PLDT

and ETPI arrived at a Letter-Agreement which contains, among others, that they shall continue to

negotiate within the shortest possible time for a mutually acceptable agreement which will amend

our existing Compromise Agreement which was approved by the Court; that without prejudice to

other claims of PLDT and ETPI against each other, they will settle amicably or through arbitration;

they likewise agree that to facilitate the resolution of our respective claims and the execution of a

new agreement which shall supersede the Compromise Agreement, both PLDT and ETPI shall not

take any action that will in any way violate the Compromise Agreement.

Subsequently, PLDT advised ETPI that it would be implementing a complete blocking of

telephone service traffic from REACH Hong Kong carried on the ETPI-REACH circuits if the

settlement rate arrangements for telephone service between Hong Kong and the Philippines were

not resolved on or before a certain date.

RTC favored ETPI defendant, PLDT was ordered to restore the free flow of

telecommunication calls and data from the Philippines to Hongkong passing through the REACHETPI circuits since the same was in violation of the Compromise Agreement.

Thus, PLDT filed with the Court of Appeals a Petition for Certiorari , which was granted.

However, later on it amended its own decision, reversing it on the ground that after the approval of the

Compromise Agreement by the RTC, the decision based on the judicial compromise between the

parties became immediately final and executory. NTC although having original and exclusive

jurisdiction over resolving disputes between telecommunications companies regarding settlement

of access charge and/or revenue sharing, it did not divest the trial court of its jurisdiction to enforce

its judgment through the issuance of the necessary writs.

With respect to the execution of the Letter-Agreement, the Court of Appeals held that the

same did not revise, modify or novate the Compromise Agreement.

Issue:

1) Whether or not RTC retained jurisdiction over the subject matter sought to be enjoined

by ETPI.

2) Whether or not the Letter-Agreement novated the Compromise Agreement when the

former expressly provided that the parties respective claims against each other should

be settled amicably or through arbitration.

Ruling:

Page 22 of 350

Justice Teresita Leonardo-De Castro Cases (2008- Remedial Law

2015)

No. After a thorough review of the facts and issues of the instant petition, the Court finds

that, the same is already moot.