Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

What Is Evaluation of Hematuria by Primary Care Physicians Use of

Transféré par

Mischell Lázaro OrdonioTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

What Is Evaluation of Hematuria by Primary Care Physicians Use of

Transféré par

Mischell Lázaro OrdonioDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations 32 (2014) 128 134

Original article

What is evaluation of hematuria by primary care physicians? Use of

electronic medical records to assess practice patterns with intermediate

follow-up

Anna Buteau, B.S.a,1, Casey A. Seideman, M.D.a,1, Robert S. Svatek, M.D.b,

Ramy F. Youssef, M.D.a, Gaurab Chakrabarti, B.S.a, Gary Reed, M.D.c, Deepa Bhat, M.D.c,

Yair Lotan, M.D.a,*

a

Department of Urology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX

Department Urology, University of Texas Health Science Center of San Antonio, San Antonio, TX

c

Department of Internal Medicine, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX

Received 11 June 2012; received in revised form 5 July 2012; accepted 7 July 2012

Abstract

Background: To determine whether patients found to have hematuria by their primary care physicians are evaluated according to best

practice policy.

Materials and methods: The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center maintains institutional outpatient electronic medical

records (EMR) that are used by all providers in all specialties. We conducted an Institutional Review Board approved observational study

of patients found to have more than 5 red blood cells/high power field between March 2009 and February 2010.

Results: There were 449 patients of whom the majority were female (82%), Caucasian (39%), with microscopic hematuria (MH) (85%).

Almost 58% of patients were initially symptomatic with urinary symptoms or pain. Evaluation for the source of hematuria was limited and

included imaging (35.6%), cystoscopy (9%, and cytology (7.3%). Only 36% of men and 8% of women were referred to a urologist. No

abnormality was found in 32% and 51% of patients with gross hematuria and MH, respectively (P 0.004). There were 4 bladder tumors

and 1 renal mass detected. Male gender, ethnicity and gross (vs. microscopic) hematuria were associated with higher rate of urological

referral. Advanced age, smoking, provider practice type, and the presence of urinary symptoms were not associated with an increase rate

of urological referral. No additional cancers were diagnosed with 29-month follow-up.

Conclusions: While urinalysis remains a common diagnostic tool, most cases of both microscopic and gross hematuria are not fully

evaluated according to guidelines. Use of cystoscopy, cytology, and upper tract imaging is limited. Further studies will be needed to

determine the extent of the problem and impact on morbidity and survival. 2014 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Primary care physicians; Hematuria; Electronic medical records; Compliance; Referral

1. Introduction

Hematuria is a highly prevalent condition affecting up to

16% of the adult population [1,2]. The condition varies by

age and gender, depending on the definition of hematuria,

and whether the testing utilizes dipstick testing or mi-

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

* Corresponding author. Tel.: 1-214-648-0483; fax: 1-214-6488786.

E-mail address: yair.lotan@utsouthwestern.edu (Y. Lotan).

1

These authors contributed equally to this work.

1078-1439/$ see front matter 2014 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2012.07.001

croscopy [1,2]. Gross hematuria is defined as blood in the

urine visible without microscopy. While the exact definition of microscopic hematuria is debated, most urologists consider 3 or more red blood cells (RBCs) per high

power field (HPF) as an abnormal finding [1,2]. The

finding of microscopic hematuria is associated with urological malignancy in approximately 2%5% of patients

depending on whether the study was population-based

(lower risk) or referral-based (higher risk) [1 4]. The

risk of urological malignancy is higher in patients with

gross hematuria, ranging from 10% to 20% [57]. Furthermore, there are non-life-threatening conditions, such

A. Buteau et al. / Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations 32 (2014) 128 134

as urinary tract infection, medical renal disease, or kidney stones, which can be found in some cases.

The evaluation of patients with hematuria is not standardized among all specialties. The American Urologic Association best practice policy recommends that all patients

with nonglomerular hematuria at high-risk for bladder cancer (especially those over age 40 years or with a history of

smoking or chemica l exposure) should be considered for a

full urological evaluation after 1 positive properly performed urinalysis [8]. In patients with suspected benign

causes for microscopic hematuria or urinary tract infection

(UTI) and low risk for malignancy based on age, smoking,

and environmental risk, a repeat urinalysis is recommended

before a complete evaluation [8]. A complete urological

evaluation of microscopic hematuria includes radiological

imaging of the upper urinary tracts followed by cystoscopic

examination of the urinary bladder [8]. A clinical practice

article by Cohen and Brown recommended complete evaluation for patients with dipstick positive for microscopic

blood who have risk factors for bladder cancer [1]. By

contrast, they recommend repeating a urinalysis for patients

at low risk prior to complete evaluation. For nonglomerular

hematuria, they recommended a helical computed tomography (CT) and cytologic evaluation of the urine. Cystoscopy

is recommended for patients over the age 50 years or risk

factors for bladder cancer.

Most studies of hematuria are based on referred populations, yet urinalyses are frequently utilized in routine evaluations by primary care physicians. The actual practice

patterns of primary care physicians are unclear and can

impact outcomes of patients with hematuria. Surveys of

primary care physicians found that only 36% 48% of patients with microscopic hematuria are referred for urological

evaluation [9,10]. A review from a health plan database

found that only 27% and 47% of women and men with

hematuria were referred to urologists [11]. Another recent

study including subjects over the age of 50 years with

greater than 10 pack/year of smoking found that only 12.8%

of patients with microscopic hematuria were referred to a

urologist for cystoscopic evaluation [12].

An important question centers on what evaluation is

performed on patients with hematuria. Complete evaluation

with cystoscopy is primarily performed by urologists, yet

the primary care physician is the gatekeeper who largely

determines which patient will receive a referral. The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center uses computerized electronic medical records (EMR) for all inpatient

and outpatient encounters. In this study, all patients with

greater than 5 RBC/HPF were identified and charts were

reviewed to determine what testing was performed on each

individual.

The advantages of this approach is that it allows a

comprehensive understanding of practice patterns compared with just evaluating referred patients which are

subject to selection bias and survey results from primary

care providers, which could vary from actual clinical

129

practice. We also were able to follow-up on patients

regardless of evaluation to determine if cancers were

diagnosed after initial evaluation.

2. Materials and methods

The EMR at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School was queried for all patients who underwent a

urinalysis with microscopy and had greater than 5 RBCs per

HPF between March 2009 and February 2010. The study

was approved by the local institutional review board.

Review of records identified 632 patients with urinalysis

meeting the above criteria. Patients were excluded if they

were already seeing a urologist, undergoing chemotherapy,

were recently hospitalized or catheterized, or were followed

by providers outside of our institution for part of their care.

The study population narrowed to 449 and included patients

with both gross and microscopic hematuria. Microscopic

hematuria was defined as 5 or more red blood cells per high

power field without visible blood per patient or physician

report. Gross hematuria was defined as visible blood reported by either the patient or the physician. For each

patient, progress notes, medical transcripts, imaging results,

laboratory results, and referrals were reviewed. Those patients who had 2 consecutive urinalyses with greater than 5

RBCs/HPF but without signs of infection were determined

to need further workup, and of that group, those who underwent upper urinary tract imaging and cystoscopy were

considered to have been fully evaluated. The EMR was

queried again in 1/2,012 to determine if any malignancy

(renal or bladder) was diagnosed.

Statistical analysis was performed using Fishers exact

test as a 1-tailed test, and 2 analysis with significance at

0.05. All analyses were performed with SPSS ver. 19.0

(SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

3. Results

Patient demographics are highlighted in Tables 1 and 2.

In this cohort, most patients were female (82%), Caucasian

(38.5%), with microscopic hematuria (85%). Most of the

patients were seen by primary care physicians with nearly

50% by internal medicine physicians. Almost 57% of the

patients were initially symptomatic with urinary symptoms

or pain. There were no statistical differences in gender,

ethnicity, and age between patients with gross and microscopic hematuria.

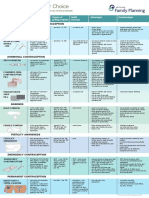

The extent of evaluation that patients underwent is

shown in Table 3, and Fig. 1. Of the patients who were not

immediately referred to Urology, 42.5% of patients with

microscopic hematuria and 43.9% of patients with gross

hematuria did not have a repeat urinalysis. In this group,

repeat urinalysis was performed on 57.5% of patients with

microscopic hematuria, with 21.2% and 36.3% of patients

130

A. Buteau et al. / Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations 32 (2014) 128 134

Table 1

Demographics of entire cohort

All patients

Number (%)

Total cohort

Gender

Male

Female

Ethnicity

White

Black

Hispanic

Asian

Other

Unknown

Age

Mean (median)

Range

Type of provider

Internal medicine

Family practice

OB/GYN

Other

Tobacco exposure

Current smoker

Ex smoker

Nonsmoker

Symptoms

Asymptomatic

Symptomatic

Gross

Number (%)

Microscopic

Number (%)

449 (100)

69 (15.4)

380 (84.6)

82 (18.3)

367 (81.7)

20 (24.4)

49 (13.4)

62 (75.6)

318 (86.6)

0.017

173 (38.5)

62 (13.8)

20 (4.5)

5 (1.1)

25 (5.8)

164 (36.5)

33 (19.1)

10 (16.1)

2 (10)

0 (0)

2 (8)

22 (13.4)

140 (80.9)

52 (83.9)

18 (90)

5 (100)

23 (92)

142 (86.6)

0.011

55.5 (55.5)

896

56.7 (58.5)

889

55.3 (55)

1796

0.550

222 (49.4)

47 (10.5)

46 (10.2)

134 (29.8)

39 (17.6)

11 (23.6)

8 (17.4)

11 (8.2)

183 (82.4)

36 (76.6)

38 (82.6)

123 (91.8)

0.035

38 (8.5)

92 (20.5)

319 (71)

6 (15.8)

18 (19.6)

45 (14.1)

32 (84.2)

74 (80.4)

274 (85.9)

0.440

193 (43)

256 (57)

39 (20.2)

30 (11.7)

154 (79.8)

226 (88.3)

0.010

with a positive and negative repeat urinalysis, respectively.

Thirty percent of patients had a documented urinary tract

infection, including 26% and 51% of patients with microscopic and gross hematuria, respectively. Cytology was

rarely (6.2%) performed and was positive in 2 (0.7%) patients. Cystoscopy was performed in 40 patients (9%). Imaging was performed in 160 (35.6%) of the patients with

CT, and ultrasound (US) represented most tests utilized.

Based on the evaluation performed, no abnormality was

found in 32% of patients with gross hematuria and 51% of

patients with microscopic hematuria (P 0.004) [Table 4].

A UTI was found in 51% and 26% of patients with gross

and microscopic hematuria, respectively (P 0.001). There

were 4 bladder tumors found and 1 renal tumor; but only 40

patients (9%) underwent cystoscopy and 64.4% of patients

had no imaging. The likelihood of referral was impacted by

gender, with 40% and 14% of men and women referred to

see a urologist, respectively [Table 5]. Patients with gross

P value

hematuria were also more likely to be referred. However,

there was no impact of age, type of provider, and presence

of symptoms on referral rates. Interestingly, smokers were

no more likely to be referred than nonsmokers (never and

previous).

Since patients with different clinical presentations have

different risk for cancer and different rationale for evaluation, we categorized our patient population into subgroups,

including symptomatic patients with UTI, symptomatic patients without evidence of UTI, asymptomatic gross hematuria, asymptomatic microhematuria on 2 analyses, and

asymptomatic microhematuria on a single analysis. Table 6

demonstrates the breakdown of patients. Of note, not all

patients had urine culture data available and, therefore, the

total number of patients does not equal 449. Patients with

asymptomatic gross hematuria were more likely to be referred to a urologist (P 0.041) and be diagnosed with

cancer, yet only 33% were referred. Patients with asymp-

Table 2

Age and gender demographics

Age (years)

40 (n 92)

4050 (n 82)

50 (n 275)

Males (n 82)

Females (n 367)

Gross (n 20)

Microscopic (n 62)

Gross (n 49)

Microscopic (n 318)

2 (10)

3 (15)

15 (75)

8 (13)

8 (13)

46 (74)

11 (22.4)

10 (20.4)

28 (57.2)

71 (22.3)

61 (19.2)

186 (58.5)

A. Buteau et al. / Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations 32 (2014) 128 134

131

Table 3

Type of evaluation of entire cohort (n 449)

Repeat UA*

None

Negative

Positive

Urine culture

None

Negative

Positive

Cytology

None

Negative

Positive

Cystoscopy

None

Negative

Positive

Imaging

None

Negative

Positive

Imaging modality

CT

US

MRI

KUB

IVP

Complete evaluation

Cystoscopy upper tract imaging

All patients (n 449)

Gross (n 69)

Microscopic (n 380)

156 (42.6)

135 (36.9)

75 (20.5)

18 (11.5)

17 (12.6)

6 (8)

138 (88.5)

118 (87.4)

69 (92)

167 (37.2)

150 (33.4)

132 (29.4)

11 (6.6)

23 (15.3)

35 (26.5)

156 (93.4)

127 (84.7)

97 (73.5)

416 (92.7)

31 (6.9)

2 (0.4)

55 (13.2)

12 (38.7)

2 (100)

361 (86.8)

19 (61.3)

0 (0)

409 (91)

37 (8.2)

3 (0.8)

51 (12.5)

15 (40.5)

3 (100)

358 (87.5)

22 (59.5)

0 (0)

289 (64.4)

90 (20)

70 (15.6)

40 (13.8)

12 (13.3)

17 (24.3)

249 (86.2)

78 (86.7)

53 (75.7)

94 (20.9)

57 (12.7)

4 (1)

4 (1)

1 (0.2)

37 (8.2)

26 (27.7)

2 (3.5)

0 (0)

0 (0)

0 (0)

17 (45.9)

68 (72.3)

55 (96.5)

4 (100)

4 (100)

1 (100)

20 (54.1)

P value

0.591

0.001

0.001

0.001

0.030

0.001

* Patient population only included patients who were not immediately referred to urology (n 366).

tomatic microhematuria one time were significantly less

likely to be referred (P 0.015), and 83% had no imaging

or cystoscopic evaluation.

Among patients with symptomatic UTIs, neither smoking, age, referring physician, gender, nor ethnicity were

predictive of workup or referral. Of symptomatic patients

with no evidence of UTI, male gender was predictive of

referral (43.4% of men vs. 17.5% of women, P 0.003)

and imaging (78.3% vs. 42.1%, P 0.003). Similarly

among patients with asymptomatic gross hematuria, male

Fig. 1. Testing performed on hematuria population. (Color version of figure is available online.)

132

A. Buteau et al. / Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations 32 (2014) 128 134

Table 4

Final diagnosis of entire cohort

None

UTI

Renal cyst

Stones

Hydronephrosis

Inflammatory cystitis

Bladder diverticula

Cancer (bladder n 4,

kidney n 1)

All patients (n 449)

Gross (n 69)

Microscopic (n 380)

P value

215 (47.9)

132 (29.4)

48 (10.7)

18 (4)

6 (1.3)

3 (0.7)

1 (0.2)

5 (1.1)

22 (31.9)

35 (26.5)

7 (14.6)

6 (33.3)

1 (16.7)

3 (100)

0 (0)

5 (100)

193 (50.8)

97 (73.5)

41 (85.4)

12 (66.7)

5 (83.3)

0 (0)

1 (100)

0 (0)

0.004

0.001

0.063

0.022

0.063

0.001

0.130

0.000

gender was predictive of referral (90% of men vs. 13.8% of

women, P 0.000) and imaging (80%of men vs. 20.7%

women, P 0.001). Additionally, in this subgroup, patients

referred by primary care providers (family medicine, internal medicine) were less likely to be referred to a urologist

(17.2% of patients seen by primary care were referred, vs.

80% of patients seen by another specialist or emergency

room physician, P 0.004). Smokers with asymptomatic

microhematuria two times on analysis were more likely to

be referred to a urologist (29% vs. 22% nonsmokers, P

0.046) but there was no impact of gender, age, ethnicity, or

referring physician. Over an average of 29-months followup, no additional cancers were detected in this cohort.

4. Discussion

The finding of hematuria is vexing for clinicians. Hematuria is an alarm of a potential life-threatening disease but

frequently serves as a false alarm with as many as 70%

90% of patients with microscopic hematuria and 50% of

patients with gross hematuria undergoing a nondiagnostic

evaluation [3,7,13]. There are many benign causes of hematuria, including physical activity, trauma, viral infections, menstruation, and sexual activity that resolve in a

short period (8). While hematuria in adults is highly prevalent, affecting up to 16% of the population during their

lifetime [1], each primary care physician may only see a

Table 5

Demographics of patients referred for evaluation, referred for evaluation who did not comply and those not referred number (%)

Gender

Male

Female

Ethnicity

White

Black

Hispanic

Asian

Other

Unknown

Age

40

4050

50

Type of provider

Internal medicine

Family practice

OB/GYN

Other

Tobacco exposure

Current smoker

Ex-smoker

Nonsmoker

Symptoms

Asymptomatic

Symptomatic

Type of hematuria

Gross

Microscopic

No referral (%)

Referred (%)

P value

82 (18.3)

367 (81.7)

49 (59.8)

317 (86.4)

33 (40.2)

50 (13.6)

0.000

173 (38.5)

62 (13.8)

20 (4.5)

5 (1.1)

25 (5.8)

164 (36.5)

137 (79.2)

52 (83.9)

19 (95)

5 (100)

20 (80)

133 (81)

36 (20.8)

10 (16.1)

1 (5)

0 (0)

5 (20)

27 (16.9)

0.001

92 (20.5)

82 (18.2)

275 (61.3)

80 (87.0)

68 (83.0)

219 (79.6)

12 (13)

14 (17)

56 (20.4)

0.657

222 (49.4)

47 (10.5)

46 (10.2)

134 (29.8)

184 (82.9)

40 (85.1)

34 (74)

108 (80.6)

38 (17.1)

7 (14.9)

12 (26.1)

26 (19.4)

0.472

38 (8.5)

92 (20.5)

319 (71)

29 (76.3)

72 (78.3)

265 (83.1)

9 (23.7)

20 (21.7)

54 (16.9)

0.398

193 (43)

256 (57)

152 (78.8)

214 (83.6)

41 (21.2)

42 (16.4)

0.191

69 (15.4)

380 (84.6)

41 (59.4)

325 (85.5)

28 (40.6)

55 (14.5)

0.000

A. Buteau et al. / Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations 32 (2014) 128 134

133

Table 6

Evaluation of patients based on clinical state

Total patients

Symptomatic UTI

All others

Symptomatic No UTI

All others

Asymptomatic GH

All others

Asymptomatic MHx2

All others

Asymptomatic MHx1

All others

Referred

449

39

410

80

369

39

410

94

355

60

389

83

10 (25.7%)

73 (17.8%)

20 (25%)

63 (17.1%)

13 (33.3%)

70 (17%)

24 (25.5%)

59 (16.6%)

4 (6.7%)

79 (20.3%)

0.167

0.178

0.041

0.138

0.015

Imaging

160

17 (43.6%)

143 (34.9%)

42 (52.5%)

118 (32%)

14 (35.9%)

146 (35.6%)

46 (48.9%)

114 (32.1%)

10 (16.7%)

150 (38.6%)

0.297

0.001

0.971

0.002

0.001

handful of cases a year. One study in the UK found that the

average general practitioner with a list size of 2000 patients

will see only 1 new case of bladder cancer every 2 years and

a new case of kidney cancer every 5 years [14]. One can

understand how it would be difficult for an individual clinician to assess the impact of management of a few patients

with microscopic hematuria. Most patients with microscopic hematuria do not have malignancy and yet, as a

whole, the absolute number of cases of bladder cancer in

patients with microscopic hematuria is significant. In a

study of urine-based tumor markers in 1,331 patients with

hematuria there were 38 cases of bladder cancer among

1,005 patients with microscopic hematuria and 39 cases of

bladder cancer among 212 cases of gross hematuria [15,16].

While the likelihood of bladder cancer is much lower in

patients with microscopic hematuria compared with gross

hematuria, the prevalence of microscopic hematuria is much

greater than gross hematuria.

In this population of patients with hematuria, very few

patients (n 37, 8.2%) underwent a complete evaluation,

including cystoscopy and upper tract imaging. Of the patients who were not immediately referred to Urology, 42.5%

of patients with microscopic hematuria and 43.9% of patients with gross hematuria did not have a repeat urinalysis.

Cytology was rarely (6.2%) performed, cystoscopy was

performed in 40 patients (9%) and imaging was performed

in 160 (35.6%) of patients with CT and US representing

most tests utilized. The population was dominated by

women (85%) and 29% of the population had urinary tract

infections. Women are much less likely than men to have

bladder cancer but women with bladder cancer are more

likely to die of their disease once diagnosed [17]. Currently,

hematuria is the main symptom used to diagnose bladder

cancer and no screening is recommended. As a consequence, 25% of patients present with advanced disease and

up to 50% of these patients will die of their disease within

5 years [17]. Delays of diagnosis are one potential cause for

the high rate of invasive disease at diagnosis and can impact

cancer-related mortality [18]. This may be more significant

in women since UTIs are often blamed as the source of

hematuria.

Cystoscopy

40

8 (20.5%)

32 (7.1%)

9 (11.3%)

31 (8.4%)

6 (15.4%)

34 (8.3%)

15 (16%)

25 (7%)

0

40 (10.3%)

0.015

0.392

0.137

0.013

0.005

Cancer

5*

1 (2.6%)

3 (0.7%)

1 (1.3%)

3 (0.8%)

2 (5.1%)

2 (0.5%)

0 (0%)

4 (1.1%)

0 (0%)

4 (1%)

No evaluation

0.485

0.836

0.000

0.512

0.677

287

22 (56.4%)

265 (64.6%)

38 (47.5%)

249 (67.5%)

25 (64.1%)

262 (63.9%)

46 (48.9%)

241 (67.9%)

50 (83.3%)

237 (60.9%)

0.302

0.001

0.980

0.001

0.001

The clinical presentation of patients will usually dictate

decisions regarding evaluation. Patients with urinary tract

infections do not need further evaluation if their hematuria

resolves and there is no additional evidence of bleeding

once infection resolves. As such, it is not surprising or

inappropriate that most patients did not get a complete

evaluation but many did not get a repeat urinalysis as

recommended [8]. By contrast, patients with asymptomatic

gross hematuria are at a high (10%20%) risk of a serious

medical problem and the fact that only 40% were referred to

Urology for evaluation is concerning. Particularly dramatic

was the difference in referral and imaging based on gender

in this cohort. It is also concerning that primary care physicians were less likely to refer to urologists then emergency

room or specialists since primary care providers (PCPs) are

more likely to see patients on a routine basis or to resolve

non-urgent issues. Patients with 2 occurrences of microscopic hematuria are recommended to undergo evaluation

but this only happened 25% of the time. While smoking had

a small but significant impact on referral (29% vs. 22%

nonsmokers, P 0.046), other risk factors, such as age and

gender, did not have an effect.

The fact that previous studies have shown a higher incidence of cancer in referred populations compared to population-based studies suggests that a selection bias exists in

studies based on referrals [1 4]. The question that remains

is how and why some patients get referred while others are

simply observed? It is not clear from our population that

many patients would even meet criteria for referral. Certainly patients with gross hematuria and those who had a

repeat urinalysis that still demonstrated more than 5 RBCs/

HPF met criteria. Many of the women who had UTIs and

some of the women who never had a repeat urinalysis may

have not met criteria for further evaluation but without

repeating a urinalysis as recommended, it is not possible to

know. It is also possible that some of the patients will

develop malignancies over time. A study using the UK

general practice research database evaluated 11,138 first

occurrences of hematuria out of 762,325 patients [13]. Urinary tract malignancies occurred in 5.5% and 2.5% of

women in the first 6 months after diagnosis, respectively,

134

A. Buteau et al. / Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations 32 (2014) 128 134

but this increased to 7.4% of men and 3.4% of women by 3

years [13]. Interestingly, with an average of 29-months

follow-up, there were no additional cancers found, however,

many of the patients had no additional evaluations.

One consideration in evaluation of patients with hematuria is that the guidelines are very broad. The AUA guidelines recommend an evaluation for all patients over the age

of 40 with any risk factor, yet the incidence of bladder or

kidney cancer for a woman in her 40s who has never

smoked is incredibly low [17]. It is possible that the lack of

selectivity of the guidelines has reduced utilization even in

patients with higher risk, such as older men with a smoking

history. Our previous study in men over the age of 50 years

with 10 years smoking history found that only 12.8% of

patients with microscopic hematuria were referred to a urologist for cystoscopic evaluation [12]. Future studies to determine the adherence to guidelines and methods for improving selection of patients for evaluation are needed. It is

possible that addition of urine-based tumor markers may

improve selection of higher risk patients for evaluation [19].

Perhaps most importantly, there is a need for studies to

assess the impact of timely evaluation of hematuria on

survival from urological malignancies.

There are several limitations with this study. We arbitrarily chose 5 RBCs/HPF as a cutoff for evaluation, but

some guidelines use 23 RBCs/HPF or even dipstick positivity for blood as criteria for microhematuria. Our goal was

to be sure that the microhematuria would not be borderline but, as a consequence, we may have underestimated

the extent of the problem. Additionally, some women were

of childbearing age, and menstruation was not assessed. The

use of EMR allows a comprehensive review of all testing

performed at our institution but it is possible that some

patients were seen elsewhere and that this was not documented by their primary care physician. Upon re-examination of the EMR at a later date, there were no additional

cases of cancer diagnosed, however, this does not exclude

the possibility that patients may have transferred care, or

were lost to follow-up.

5. Conclusions

While urinalysis remains a common routine diagnostic

tool, most cases of microscopic hematuria are not fully

evaluated according to guidelines. Many patients with hematuria and either a urinary tract infection or 1 positive

urinalysis never have further evaluation. Use of cystoscopy,

cytology, and upper tract imaging is limited. Further studies

will be needed to determine the extent of the problem and

impact on morbidity and survival.

References

[1] Cohen RA, Brown RS. Clinical practice. Microscopic hematuria.

N Engl J Med 2003;348:2330 8.

[2] Grossfeld GD, Litwin MS, Wolf JS, et al. Evaluation of asymptomatic microscopic hematuria in adults: The American Urological Association best practice policyPart I: Definition, detection, prevalence, and etiology. Urology 2001;57:599 603.

[3] Mariani AJ, Mariani MC, Macchioni C, et al. The significance of

adult hematuria: 1,000 hematuria evaluations including a risk-benefit

and cost-effectiveness analysis. J Urol 1989;141:350 5.

[4] Britton JP, Dowell AC, Whelan P, et al. A community study of

bladder cancer screening by the detection of occult urinary bleeding.

J Urol 1992;148:788 90.

[5] Bruyninckx R, Buntinx F, Aertgeerts B, et al. The diagnostic value of

macroscopic haematuria for the diagnosis of urological cancer in

general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2003;53:315.

[6] Buntinx F, Wauters H. The diagnostic value of macroscopic haematuria in diagnosing urological cancers: A meta-analysis. Fam Pract

1997;14:63 8.

[7] Khadra MH, Pickard RS, Charlton M, et al. A prospective analysis of

1,930 patients with hematuria to evaluate current diagnostic practice.

J Urol 2000;163:524 7.

[8] Grossfeld GD, Litwin MS, Wolf JS Jr., et al. Evaluation of asymptomatic microscopic hematuria in adults: The American Urological

Association best practice policyPart II: Patient evaluation, cytology,

voided markers, imaging, cystoscopy, nephrology evaluation, and

follow-up. Urology 2001;57:604 10.

[9] Nieder AM, Lotan Y, Nuss GR, et al. Are patients with hematuria

appropriately referred to urology? A multi-institutional questionnaire

based survey. Urol Oncol 2010;28(5):500 3.

[10] Yafi FA, Aprikian AG, Tanguay S, et al. Patients with microscopic

and gross hematuria: Practice and referral patterns among primary

care physicians in a universal health care system. Can Urol Assoc J

2011;5:97101.

[11] Johnson EK, Daignault S, Zhang Y, et al. Patterns of hematuria

referral to urologists: Does a gender disparity exist? Urology 2008;

72:498 502; Discussion:5023.

[12] Elias K, Svatek RS, Gupta S, et al. High-risk patients with hematuria

are not evaluated according to guideline recommendations. Cancer

2010;116:2954 9.

[13] Jones R, Latinovic R, Charlton J, et al. Alarm symptoms in early

diagnosis of cancer in primary care: Cohort study using general

practice research database. BMJ 2007;334:1040.

[14] Summerton N, Mann S, Rigby AS, et al. Patients with new onset

haematuria: Assessing the discriminant value of clinical information

in relation to urological malignancies. Br J Gen Pract 2002;52:284 9.

[15] Lotan Y, Shariat SF. Impact of risk factors on the performance of the

nuclear matrix protein 22 point-of-care test for bladder cancer detection. BJU Int 2008;101:13627.

[16] Grossman HB, Messing E, Soloway M, et al. Detection of bladder

cancer using a point-of-care proteomic assay. JAMA 2005;293:

810 6.

[17] Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A, et al. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA

Cancer J Clin 2012;62:10 29.

[18] Wallace DM, Raghavan D, Kelly KA, et al. Neoadjuvant (preemptive) cisplatin therapy in invasive transitional cell carcinoma of the

bladder. Br J Urol 1991;67:60816.

[19] Lotan Y, Capitanio U, Shariat SF, et al. Impact of clinical factors,

including a point-of-care nuclear matrix protein-22 assay and

cytology, on bladder cancer detection. BJU Int 2009;103(10):

1368 74.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Siddharth Agrawal - Strabismus - For Every Ophthalmologist-Springer Singapore (2019) PDFDocument177 pagesSiddharth Agrawal - Strabismus - For Every Ophthalmologist-Springer Singapore (2019) PDFMischell Lázaro Ordonio100% (1)

- MicroPulse - P3 Rev 2 - Cyan MedicaDocument6 pagesMicroPulse - P3 Rev 2 - Cyan MedicaMischell Lázaro OrdonioPas encore d'évaluation

- Etiology and evaluation of hematuria in adultsDocument16 pagesEtiology and evaluation of hematuria in adultsMischell Lázaro OrdonioPas encore d'évaluation

- Secondary Prevention Early Onset GBS Disease Among NewbornsDocument1 pageSecondary Prevention Early Onset GBS Disease Among NewbornsMischell Lázaro OrdonioPas encore d'évaluation

- Systemic Effects of Perinatal AsphyxiaDocument7 pagesSystemic Effects of Perinatal AsphyxiaMischell Lázaro OrdonioPas encore d'évaluation

- Hematuria ClasificacionDocument4 pagesHematuria ClasificacionMischell Lázaro OrdonioPas encore d'évaluation

- Current Concepts in The Pathogenesis andDocument14 pagesCurrent Concepts in The Pathogenesis andMischell Lázaro OrdonioPas encore d'évaluation

- Findings Neonatal SepsisDocument1 pageFindings Neonatal SepsisMischell Lázaro OrdonioPas encore d'évaluation

- Clinical Features, Evaluation, and Diagnosis of Sepsis in Term and Late Preterm InfantsDocument12 pagesClinical Features, Evaluation, and Diagnosis of Sepsis in Term and Late Preterm InfantsMischell Lázaro OrdonioPas encore d'évaluation

- Bacteria Sepsis Term InfantDocument1 pageBacteria Sepsis Term InfantMischell Lázaro OrdonioPas encore d'évaluation

- Neonatal Sepsis Differential DiagnosisDocument1 pageNeonatal Sepsis Differential DiagnosisMischell Lázaro OrdonioPas encore d'évaluation

- Docena DiabetesDocument3 pagesDocena DiabetesMischell Lázaro OrdonioPas encore d'évaluation

- Pancreatitis 2015Document35 pagesPancreatitis 2015Mischell Lázaro OrdonioPas encore d'évaluation

- Chep 2016Document70 pagesChep 2016Mischell Lázaro OrdonioPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Octeto de DefronzoDocument23 pages1 Octeto de DefronzoLesli Rodriguez50% (2)

- Hematuria ClasificacionDocument4 pagesHematuria ClasificacionMischell Lázaro OrdonioPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Paraphimosis (Ingles)Document1 pageParaphimosis (Ingles)Joaquín SosaPas encore d'évaluation

- Interstitial Cystitis (Bladder Inflammation) - ColumbiaDoctors - New YorkDocument6 pagesInterstitial Cystitis (Bladder Inflammation) - ColumbiaDoctors - New YorkJimmy GillPas encore d'évaluation

- SOP: Urinary Catheter in Dogs and CatsDocument6 pagesSOP: Urinary Catheter in Dogs and CatsMas HendryPas encore d'évaluation

- The TURP Procedure StepDocument3 pagesThe TURP Procedure Stepnorhafizahstoh89100% (1)

- Confirmed COVID-19 Confirmed COVID-19Document5 pagesConfirmed COVID-19 Confirmed COVID-19ilham masdarPas encore d'évaluation

- Effects of Transurethral Resection of Prostate (Turp) On Uroflowmetry Parameters On Patients Having Benign Prostatic HyperplasiaDocument6 pagesEffects of Transurethral Resection of Prostate (Turp) On Uroflowmetry Parameters On Patients Having Benign Prostatic HyperplasiaKamran AfzalPas encore d'évaluation

- Urinary Infections in The ElderlyDocument29 pagesUrinary Infections in The ElderlyChris FrenchPas encore d'évaluation

- Quick Start Guides For Urodynamics Testing V06 (MAN247)Document62 pagesQuick Start Guides For Urodynamics Testing V06 (MAN247)prathibhasaseedharanPas encore d'évaluation

- Management of Renal Stones: Theme From January 2013 ExamDocument123 pagesManagement of Renal Stones: Theme From January 2013 ExamBela VitoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- 4 - Surgical Treatment of BPHDocument55 pages4 - Surgical Treatment of BPHKsatria DressrosaPas encore d'évaluation

- CGHS Chennai Empanelled Hospital List As On Apr 23Document7 pagesCGHS Chennai Empanelled Hospital List As On Apr 23Banumathy RajappaPas encore d'évaluation

- UrethralbladderinjuryDocument32 pagesUrethralbladderinjuryNinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Pelvic Inflammatory DiseaseDocument4 pagesPelvic Inflammatory DiseasekabebangPas encore d'évaluation

- Ureteroscopy Techniques and Outcomes for Treating Kidney Stones and CancerDocument66 pagesUreteroscopy Techniques and Outcomes for Treating Kidney Stones and CancerCentanarianPas encore d'évaluation

- Catheterization ProcedureDocument3 pagesCatheterization ProcedureAbigail BascoPas encore d'évaluation

- Genitourinary trauma guideDocument42 pagesGenitourinary trauma guideOrin SujasmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Sales & Distribution Project: Contraceptive Condom DurexDocument32 pagesSales & Distribution Project: Contraceptive Condom DurexManish NeerajPas encore d'évaluation

- Referensiii NefrotiasisDocument6 pagesReferensiii NefrotiasisPramestiPas encore d'évaluation

- Case-Urinary Catheterizarion DR - PNTDocument38 pagesCase-Urinary Catheterizarion DR - PNTWan Adi OeyaPas encore d'évaluation

- FELINE URETERAL OBSTRUCTION MANAGEMENTDocument6 pagesFELINE URETERAL OBSTRUCTION MANAGEMENTvetgaPas encore d'évaluation

- Morcellation From KARL STORZDocument20 pagesMorcellation From KARL STORZimbesil123Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bagian Kedua Tes Bahasa Inggris (Nomor 121 S.D. 180) Structure and Written ExpressionDocument5 pagesBagian Kedua Tes Bahasa Inggris (Nomor 121 S.D. 180) Structure and Written ExpressionFredy Allan SusantoPas encore d'évaluation

- Indwelling Urinary CatheterizationDocument8 pagesIndwelling Urinary CatheterizationNiña Jean Tormis AldabaPas encore d'évaluation

- Treatmen UrologiDocument681 pagesTreatmen UrologisulthonPas encore d'évaluation

- Urinary Tract Infection - FinalDocument86 pagesUrinary Tract Infection - FinalShreyance Parakh100% (1)

- Tractus Urinarius: Departemen Anatomi Fk-Usu MedanDocument21 pagesTractus Urinarius: Departemen Anatomi Fk-Usu MedanRizky Indah SorayaPas encore d'évaluation

- 4 - CatheterizationDocument20 pages4 - Catheterizationkirstenfrancine28Pas encore d'évaluation

- Contraception Options in New ZealandDocument2 pagesContraception Options in New ZealandStuff NewsroomPas encore d'évaluation

- UroLap 2.0 - BrochureDocument3 pagesUroLap 2.0 - Brochurehindi channelPas encore d'évaluation

- Urinary RetentionDocument28 pagesUrinary RetentionSchoeb MuhammadPas encore d'évaluation