Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Small Loans - Grameen

Transféré par

NISTYear5Description originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Small Loans - Grameen

Transféré par

NISTYear5Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Small Loans, Significant Impact

They are part of a lending program created by Muhammad Yunus, a

Bangladeshi economist who won the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize for

developing the Grameen Bank, which uses micro-loans to help

eradicate poverty in developing nations.

But these women are not in Bangladesh, they are in Queens. They are

among the first 100 borrowers of Grameen America, which began

disbursing loans in January. This is the first time Grameen has run its

program in a developed country.

"I just want to live a little better, and one day own a little house or

something," said Socorro Diaz, 54, a borrower who sells women's

lingerie and jewelry. "I'm trying to change my life. Bit by bit."

Grameen America, which offers loans from $500 to $3,000, hopes to

reach people like her, part of the large segment of poor Americans

without access to credit, said Ritu Chattree, the vice president for

finance and development.

They are bakers who can only buy enough eggs and milk for a day's

work because they cannot afford a restaurant refrigerator to store

ingredients. They are vendors who borrow money daily to rent a cart.

They are hair salon owners who take out loans every time they need

to buy shampoo.

They often use pawn shops, or fall prey to check-cashing stores, loan

sharks, and payday lenders, which can charge interest rates of 200 or

300 percent, Chattree said.

"You think this is normal, because you grew up with it," said Yunus of

such high-interest lending in a recent interview with the Financial

Times. "This is an abnormal situation, because of the problem with

the financial system, so we have to adjust the financial system."

His adjustment begins with this experiment in the immigrant

neighborhood of Jackson Heights, Queens.

Three groups of five borrowers attend the meeting in the apartment

of Jenny Guante, 40, who makes silver and gold jewelry and runs a

home day care. Some are making weekly loan payments; the largest

payment is $66 on a $3,000 loan. Guante, the group's chairwoman,

counts the money carefully before passing it to Alethia Mendez, the

Grameen staff member who serves as community banker and center

director.

"I've known these people forever," said one borrower in the roomful

of immigrants from the Dominican Republic. "We grew up together.

We went to school together around the corner."

That bond helps people make payments, said Chattree. If one woman

is having trouble repaying a loan because, say, her husband is sick

and she has to care for him and the children, another of her group

might pitch in to help with child care. Loan disbursements for the

whole group are slowed if one person defaults, she said.

After the meeting, as several women drift off into the kitchen with a

calculator to discuss their plans, 10 new prospective borrowers stop

by the apartment.

The program began in 1974, when Yunus lent $27 to a group of poor

villagers and realized that even small amounts could make

transformative differences. He set up the Grameen Bank, which has

since disbursed about $6 billion in tiny loans to about 7.4 million

Bangladeshi micro-entrepreneurs, mostly women in businesses such

as street vending and farming.

In Bangladesh, Grameen also functions as a savings bank, makes

college and housing loans, and operates projects in areas such as

telecommunications, yogurt production and solar energy.

The problem with capitalism, Yunus says, is its distinction between

companies pursuing profit and charities pursuing good. His bank

model operates with corporate efficiency, but pumps profits back

into social objectives.

The borrowers in Queens are following Grameen's self-sufficient

model in the developing world.

But Yunus acknowledges that the United States is different from the

seven countries where Grameen operates its loan programs, or the

dozens of others where Grameen has offered technical advice.

Here, there is more regulation, so a person cannot just set up a cart

and sell cakes without a permit.

The welfare system discourages income-generating activities, Yunus

says. "If you earn a dollar, that dollar is to be deducted from your

welfare check. If you want to quit welfare, then you lose your health

benefits," he told the Financial Times.

Rules for setting up a bank are cumbersome for a micro-operation,

and Yunus has met with the head of the Federal Reserve and

members of Congress to discuss creating more flexible legal

frameworks.

Other micro-lenders and academics say that if anyone can spark

discussion on the issue, Grameen can.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Acc11 Accounting For Government and Not-For-profit EntitiesDocument5 pagesAcc11 Accounting For Government and Not-For-profit EntitiesKaren UmaliPas encore d'évaluation

- Debit CardDocument22 pagesDebit CardDivya GoelPas encore d'évaluation

- Questioning Tool: Accounting Firm's Standards Are As High As They Should Be?Document2 pagesQuestioning Tool: Accounting Firm's Standards Are As High As They Should Be?Jeremy Ortega100% (1)

- See Statements - Barclays Online BankingDocument5 pagesSee Statements - Barclays Online BankingNadiia AvetisianPas encore d'évaluation

- Sounds of Alarm: BP ChallengeDocument4 pagesSounds of Alarm: BP ChallengeNISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Addition InquiryDocument1 pageAddition Inquiry19petanquepPas encore d'évaluation

- Shape QuizDocument1 pageShape QuizNISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Year - 5 - Newsletter Start of Year 2011Document2 pagesYear - 5 - Newsletter Start of Year 2011NISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Final ReviewDocument1 pageFinal ReviewNISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bar Graph 2Document1 pageBar Graph 2NISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Year - 5 - Newsletter Start of Year 2011Document2 pagesYear - 5 - Newsletter Start of Year 2011NISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Scientific Report Master1Document2 pagesScientific Report Master1NISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

- CotyDocument1 pageCotyNISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bar Graph 1Document1 pageBar Graph 1NISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Learning TargetDocument1 pageLearning TargetNISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Forest ExplanationDocument3 pagesForest ExplanationNISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

- CotyDocument1 pageCotyNISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Addition InquiryDocument1 pageAddition Inquiry19petanquepPas encore d'évaluation

- My Dream HeuiWeonDocument2 pagesMy Dream HeuiWeonNISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Year 5 NewsletterDocument2 pagesYear 5 NewsletterNISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Examples of Citing Sources AttributionDocument2 pagesExamples of Citing Sources AttributionNISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Volcano Explanation 1Document2 pagesVolcano Explanation 1NISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Coty ReviewDocument1 pageCoty ReviewNISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Juyoung My DreamDocument2 pagesJuyoung My DreamNISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

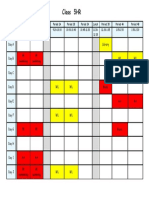

- 5HR TimetableDocument1 page5HR TimetableNISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Who We Are NewsletterDocument1 pageWho We Are NewsletterNISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Year 4 Welcome NewsletterDocument2 pagesYear 4 Welcome NewsletterNISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Taxes: Think For Yourself, Then Ask An Adult, Then Do Some Research On The Internet Then Nswer These QuestionsDocument1 pageTaxes: Think For Yourself, Then Ask An Adult, Then Do Some Research On The Internet Then Nswer These QuestionsNISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Micro Credit ThailandDocument4 pagesMicro Credit ThailandNISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

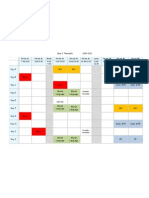

- 5JC Timetable 2010-111Document1 page5JC Timetable 2010-111NISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

- OPINION - Grameen BankDocument2 pagesOPINION - Grameen BankNISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Section 2 TableDocument1 pageSection 2 TableNISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

- KWL Fair TradeDocument2 pagesKWL Fair TradeWill KirkwoodPas encore d'évaluation

- International Monetary FundDocument2 pagesInternational Monetary FundNISTYear5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Other Comprehensive IncomeDocument11 pagesOther Comprehensive IncomeJoyce Ann Agdippa BarcelonaPas encore d'évaluation

- Askari Value PlanDocument4 pagesAskari Value PlanSyed HassanPas encore d'évaluation

- Merchant Application Form GatewayDocument4 pagesMerchant Application Form GatewaykanchansamudrawarPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 Petty Cash FundDocument8 pages2 Petty Cash FundThalia Angela HipePas encore d'évaluation

- Pru HI 6th Edition (4 Sets of Mock Combined)Document51 pagesPru HI 6th Edition (4 Sets of Mock Combined)thth943Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 4 (Kuliah) - Interest Rate and EquivalenceDocument38 pagesChapter 4 (Kuliah) - Interest Rate and EquivalenceZaki AsyrafPas encore d'évaluation

- IS and CGS ReportDocument6 pagesIS and CGS Reportロザリーロザレス ロザリー・マキルPas encore d'évaluation

- ProjectDocument111 pagesProjectGanesh KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- RHB BankDocument4 pagesRHB BankSyamil ImanPas encore d'évaluation

- 2022 Gr11 Mathematical Literacy WRKBK ENGDocument20 pages2022 Gr11 Mathematical Literacy WRKBK ENGmanganyePas encore d'évaluation

- Activity No. 3 - Principles of Accounting: AnswersDocument2 pagesActivity No. 3 - Principles of Accounting: AnswersLagasca Iris100% (1)

- History of Mutual Fund IndustryDocument5 pagesHistory of Mutual Fund IndustryB.S KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Bcc:Br:104:404 20.11.2012 Circular To All Branches and Offices in IndiaDocument12 pagesBcc:Br:104:404 20.11.2012 Circular To All Branches and Offices in IndiaamilcarPas encore d'évaluation

- Account Summary: MalaysiaDocument4 pagesAccount Summary: MalaysiaOmar MuhdPas encore d'évaluation

- The Philippine Financial SystemDocument2 pagesThe Philippine Financial SystemElizabeth CanadaPas encore d'évaluation

- For Which Item Does A Bank Not Issue A Debit Memorandum?: E. To Notify A Depositor of A Deposit To Their AccountDocument33 pagesFor Which Item Does A Bank Not Issue A Debit Memorandum?: E. To Notify A Depositor of A Deposit To Their AccountUyenPas encore d'évaluation

- Investment Has Different Meanings in Finance and EconomicsDocument15 pagesInvestment Has Different Meanings in Finance and EconomicsArun IssacPas encore d'évaluation

- A Use The Capm To Compute The Required Rate ofDocument2 pagesA Use The Capm To Compute The Required Rate ofDoreenPas encore d'évaluation

- IT Income From Other Sources Pt-2Document7 pagesIT Income From Other Sources Pt-2syedfareed596Pas encore d'évaluation

- Republic vs. First National City Bank of New YorkDocument7 pagesRepublic vs. First National City Bank of New YorkFD BalitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson 7 Mergers and AcquisitionsDocument11 pagesLesson 7 Mergers and AcquisitionsfloryvicliwacatPas encore d'évaluation

- Handbook To WSS FinalDocument38 pagesHandbook To WSS Finalrs0728Pas encore d'évaluation

- Time Value of MoneyDocument35 pagesTime Value of MoneyAswinrkrishnaPas encore d'évaluation

- HDFC Bank - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia - Part2Document1 pageHDFC Bank - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia - Part2Rahul LuharPas encore d'évaluation

- Dunlapslk PresentationDocument18 pagesDunlapslk Presentationapi-325349652Pas encore d'évaluation