Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Biased Assimilation of Sociopolitical Arguments

Transféré par

intemperanteTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Biased Assimilation of Sociopolitical Arguments

Transféré par

intemperanteDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Basic and Applied Social Psychology

ISSN: 0197-3533 (Print) 1532-4834 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hbas20

Biased Assimilation of Sociopolitical Arguments:

Evaluating the 1996 U.S. Presidential Debate

Geoffrey D. Munro , Peter H. Ditto , Lisa K. Lockhart , Angela Fagerlin ,

Mitchell Gready & Elizabeth Peterson

To cite this article: Geoffrey D. Munro , Peter H. Ditto , Lisa K. Lockhart , Angela Fagerlin ,

Mitchell Gready & Elizabeth Peterson (2002) Biased Assimilation of Sociopolitical Arguments:

Evaluating the 1996 U.S. Presidential Debate, Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 24:1, 15-26

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15324834BASP2401_2

Published online: 07 Jun 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 146

View related articles

Citing articles: 47 View citing articles

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=hbas20

Download by: [Laurentian University]

Date: 22 April 2016, At: 19:01

BIASED ASSIMILATION OF SOCIOPOLITICAL

MUNRO

ARGUMENTS

ET AL.

BASIC AND APPLIED SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY, 24(1), 1526

Copyright 2002, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Biased Assimilation of Sociopolitical Arguments: Evaluating the

1996 U.S. Presidential Debate

Geoffrey D. Munro

Department of Psychology

St. Marys College of Maryland

Peter H. Ditto

Downloaded by [Laurentian University] at 19:01 22 April 2016

Department of Psychology and Social Behavior

University of California, Irvine

Lisa K. Lockhart

Department of Psychology and Sociology

Texas A&M UniversityKingsville

Angela Fagerlin, Mitchell Gready, and Elizabeth Peterson

Department of Psychology

Kent State University

The tendency for people to rate attitude-confirming information more positively than attitude-disconfirming information (biased assimilation) was studied in a naturalistic context. Participants watched and evaluated the first 1996 Presidential Debate between Bill Clinton and Bob

Dole. Regression analyses revealed that predebate attitudes but not expectations predicted

postdebate argument evaluations and perceived attitude change. Participants evaluated the arguments that confirmed their predebate attitudes as being stronger than the arguments that

disconfirmed their predebate attitudes, and they perceived their postdebate attitudes to have become more extreme than their predebate attitudes. Self-reported affective responses mediated

the association between predebate attitudes and postdebate argument evaluations. The role of

affect in information-processing theories and the significance of the findings for sociopolitical

debates are discussed.

By exposing people to opposing political viewpoints, public

debates like those preceding presidential elections are

thought by many to lead a significant percentage of people to

undergo a rational analysis of the full range of arguments

and, ultimately, to change their opinions. Certainly, it is not

difficult to call to mind historical examples of presidential

debates that seem to have had a significant effect on public

opinion. John F. Kennedys telegenic performance in his

1960 debate against Richard Nixon is thought by many to

have boosted him into the presidency. Similarly, many political pundits believe that Ronald Reagans strong outing versus Jimmy Carter in 1980 legitimized his candidacy and cata-

Requests for reprints should be sent to Dr. Geoffrey D. Munro, Department of Psychology, St. Marys College of Maryland, St. Marys City,

MD 20686. E-mail: gdmunro@smcm.edu

lyzed his victory 1 week later on election day. In fact, some

survey data support the anecdotal evidence by suggesting

that Reagans performance did indeed produce a significant

change in the opinions of those with relatively low levels of

political knowledge (Davis, 1982; Lanoue, 1992).

Considerably more data, on the other hand, suggest that

rather than changing peoples opinions, debates simply reinforce viewers prior attitudes (Bothwell & Brigham, 1983; E.

Katz & Feldman, 1962; Kinder & Sears, 1985; Sears &

Chaffee, 1979). Sigelman and Sigelman (1984) even found

this to be true of the 1980 CarterReagan debate that was

thought to have had such a strong impact in changing voters

opinions. This research continued to investigate attitude

change and attitude reinforcement by studying the effects of

the first 1996 Presidential Debate in a setting that retained the

naturalism of a national opinion survey while controlling for

the confounds inherent in survey research.

16

MUNRO ET AL.

Downloaded by [Laurentian University] at 19:01 22 April 2016

BIASED ASSIMILATION AND ATTITUDE

RESISTANCE OF SOCIOPOLITICAL

INFORMATION

From a social psychological viewpoint, the finding that peoples political attitudes are resistant to change is not surprising. One of the hallmarks of social cognition research is that

when a person forms a belief, attitude, or expectation, that

cognition becomes relatively resistant to change regardless

of whether information presented subsequently supports or

refutes it. Research on the primacy effect (Asch, 1946; Jones,

Rock, Shaver, Goethals, & Ward, 1968; Langer & Roth,

1975; McAndrew, 1981), anchoring and insufficient adjustment (Cervone & Peake, 1986; Plous, 1989; Slovic &

Lichtenstein, 1971; Tversky & Kahneman, 1974), and the

belief perseverance effect (Anderson, Lepper, & Ross, 1980;

Jelalian & Miller, 1984; Ross, Lepper, & Hubbard, 1975)

demonstrates that initial attitudes and beliefs often bias the

way that subsequent information is processed. Specifically,

rather than accommodating the new information, the new information is assimilated to the existing cognition. The seminal work of Hastorf and Cantril (1954) exemplifies the tendency of an existing cognition like a schema to bias the

interpretation of subsequent information. On viewing an especially rough and heated football game between rivals

Dartmouth and Princeton, Dartmouth students observed

more flagrant violations committed by Princeton players,

whereas Princeton students observed more flagrant violations committed by Dartmouth players. Presumably, the existing cognition that the football team representing ones

own university consisted of tough but fair sportsmen influenced the interpretations of the violence that ensued during

the game.

Lord, Ross, and Lepper (1979) demonstrated that this effect generalized to the processing of sociopolitical information. They showed that peoples attitudes toward capital

punishment affected their evaluations of the methodologies

of two scientific studies, one with procapital punishment

conclusions and one with anticapital punishment conclusions. Participants displayed a biased assimilation of the

mixed evidence. Proponents of the death penalty appeared to

accept and integrate the results of the study suggesting that

the death penalty effectively reduces crime, but they seemed

to discount and reject the results of the study suggesting that

the death penalty does not reduce crime. Opponents of the

death penalty rated the studies in the opposite manner. In addition, Lord et al. showed that after reading and evaluating

the two studies, participants reported that their attitudes toward capital punishment had become more extreme. This

was termed attitude polarization.

The Lord et al. (1979) study has spawned a large body of

research and theoretical debate. Two issues in particular have

received a great deal of attention. First, having been studied

exclusively in the laboratory, it is difficult to know whether

biased assimilation would generalize to more naturalistic set-

tings. Second, theoretical debate has emerged as a result of

investigations attempting to uncover the causal mechanism

underlying biased assimilation.

THE EXTERNAL VALIDITY OF BIASED

ASSIMILATION AND ATTITUDE

POLARIZATION

The basic effect first documented by Lord et al. (1979) has

been replicated with several different kinds of information

and a variety of issues. Although the original study found the

biased assimilation effect using methodologically detailed

descriptions of scientific studies, it has also been found using

much shorter evidence summaries (McHoskey, 1995), persuasive essays presented via audiotape (Zuwerink & Devine,

1996), and logical arguments containing a single premise and

conclusion (Edwards & Smith, 1996). Furthermore, the effect has been shown with a variety of issues including capital

punishment (Lord et al., 1979; Miller, McHoskey, Bane, &

Dowd, 1993; Pomerantz, Chaiken, & Tordesillas, 1995), the

safety of nuclear power (Plous, 1991), the ban on gays in the

military (Zuwerink & Devine, 1996), stereotypes associated

with homosexuality (Munro & Ditto, 1997), and theories regarding the JFK assassination (McHoskey, 1995).

In each of the aforementioned studies, however, the information presented to participants was either constructed or selected by the researcher(s). It is likely that the materials were

chosen so that opposing pieces of information would be

equally balanced and thus open to alternative interpretations.

In essence, the materials were selected because they would

maximize the possibility that biased assimilation would occur. One question posed in this research is, Will the biased

assimilation effect replicate in response to naturally occurring and potentially unbalanced information like the arguments presented in a political debate? The first goal of this

research was to determine whether or not biased assimilation

can be generalized to a more naturalistic setting using information presented in real time. Specifically, will viewers of

the 1996 U.S. Presidential Debate rate the arguments of their

favored candidate more positively than the arguments of the

opposing candidate?

Another issue related to the external validity of biased assimilation and attitude polarization is the duration of the effects. Do the effects persist over time or are they limited to

the timeframe of the experimental session? If the effects are

shortlived and disappear soon after the participants exit the

laboratory, then the effect might simply be an interesting bias

found in response to certain materials presented in a laboratory context rather than a bias that might ultimately underlie

behavioral actions and hold important real-world implications. This research will further assess the external validity of

biased assimilation and attitude polarization by measuring

participants reactions to the information not only directly af-

BIASED ASSIMILATION OF SOCIOPOLITICAL ARGUMENTS

ter the presentation of the information but also 1 week later.

The endurance of peoples reactions to a presidential debate,

of course, has important implications for actual voting behavior that occurs at the very least 1 week after the debate.

Downloaded by [Laurentian University] at 19:01 22 April 2016

BIASED ASSIMILATION: A COGNITIVE

OR MOTIVATIONAL PHENOMENON

In addition to the external validity question, biased assimilation and the original interpretation of the effect have been at

the crux of a recent theoretical debate. Biased assimilation was

originally presented by Lord et al. (1979) as a purely cognitive

bias consistent with the more general social psychological

finding that expectations bias the processing of subsequent information in a manner that serves to increase the probability

that the expectancy perseveres (Darley & Gross, 1983;

Duncan, 1976; Hamilton & Rose, 1980; Merton, 1957;

Rosenthal & Jacobson, 1968; Snyder & Swann, 1978; Snyder

& Uranowitz, 1978; von Hippel, Sekaquaptewa, & Vargas,

1995; Word, Zanna, & Cooper, 1974). Others have argued that

biased assimilation could easily have been interpreted as a

motivationally based bias (Aronson, 1989, 1992; Berkowitz

& Devine, 1989) consistent with cognitive dissonance theory

(Festinger, 1957). Although the theoretical argument in support of the motivational interpretation was cogent and persuasive, it was also convincingly counterargued that without empirical evidence there is no need to expand on the more

parsimonious cognitive explanation (Lord, 1989, 1992).

More recently, empirical studies have begun to inform

this debate. Edwards and Smith (1996) showed that increased emotional conviction toward an issue is associated

with increased bias against arguments disconfirming ones

prior beliefs. Zuwerink and Devine (1996) found that resistance to change ones attitude was mediated by both thought

listings and self-reported affect. They concluded that attitude

resistance is both a cognitive and an affective phenomenon.

Finally, from data collected using a conceptual replication of

the Lord et al. (1979) paradigm, Munro and Ditto (1997) constructed a path model that was consistent with an affectivemotivational account of biased assimilation. In this

model, it was found that differential affective reactions to attitude-confirming and attitude-disconfirming information

mediated the effect of prior attitude on evaluations of the

quality of the information (i.e., biased assimilation).

Reframing the theoretical debate in terms of viewers reactions to a presidential debate, the central issue is the mechanism underlying peoples evaluations of the candidates and

their arguments. Is it a rational analysis in which the arguments are evaluated in relation to ones prior knowledge and

expectations about the debate? Or, is it an emotional process

in which the arguments are evaluated in relation to the affect

that is felt in response to the presentations of the particular

candidates? The expectancy view holds that those in favor of

17

a particular candidate expect that candidate to win, and any

information that disconfirms the expectation is processed in

a way that puts it at an evaluative disadvantage relative to information that confirms the expectation. In contrast, the affectivemotivational view holds that those in favor of a

particular candidate have positive feelings toward that candidate, and any information attacking the favored candidate

creates negative affect motivating the individual to evaluate

it more negatively than information supporting the favored

candidate. Consistent with the affectivemotivational account, research has shown that peoples emotional reactions

to presidential candidates are better predictors of overall voting preferences than are beliefs about candidates personality

traits and behaviors (Abelson, Kinder, Peters, & Fiske,

1982).

Therefore, the second goal of this research was to examine whether or not emotional reactions to presidential candidates also predict evaluative reactions to the arguments

presented by the candidates during a political debate. To

examine the role of affect as a potential mediator of the link

between prior attitudes and evaluations of the debate arguments, participants emotional reactions to the presentations of the two candidates during the debate were

measured. Also, the role of expectancy in affecting evaluations of the debate arguments was investigated by measuring participants predebate expectations about the outcome

of the debate.

METHOD

Participants

Seventy undergraduates (34 women and 36 men) at a medium-sized state university received course credit for their

participation in the study. Of the 70 participants, 60 were

successfully contacted by telephone before the second presidential debate. All analyses include only those participants

that completed the measure in question.

Procedure

The first debate between Democratic President Bill

Clinton and the Republican challenger Bob Dole took

place on October 6, 1996. Participants arrived at the experimental session half an hour before the live broadcast

of the ClintonDole debate. During this time, participants

completed consent forms as well as several measures assessing attitudes toward the election, feelings toward the

candidates, and expectations about which candidate would

win the debate. The television was turned off so participants were not exposed to any of the media predictions or

commentaries that occurred immediately prior to the debate. The live broadcast of the debate was then projected

on a film screen in a medium-sized classroom at precisely

18

MUNRO ET AL.

Downloaded by [Laurentian University] at 19:01 22 April 2016

the time when the debate started. Participants were instructed to watch the debate and evaluate the arguments of

each candidate to the best of their abilities. At the end of

the debate, the television projection was immediately terminated so that none of the postdebate media analyses or

commentaries was presented to participants. Therefore,

the arguments presented by each candidate during the debate were presented in real time as the debate was happening. After the debate, participants completed a set of

postdebate measures. Participants were then asked to provide their first names and telephone numbers if they would

agree to be called in the coming weeks to answer several

more questions. All participants provided this information.

Between 7 and 10 days later, participants were called and

asked to respond to a set of follow-up measures.

Predebate Measures

Before the debate, participants responded to three sets of

questions assessing (a) interest and involvement in the presidential campaign, (b) attitudes regarding the election and

feelings toward the candidates, and (c) expectations regarding the debate.

Involvement assessment. Participants responded to

four questions assessing their interest and involvement in the

presidential campaign. The first question was, Would you

have watched the presidential debate even if this experiment

had not been offered? on a scale ranging from 1 (absolutely

yes) to 3 (dont know) to 5 (absolutely not). The next three

questions assessed emotional involvement in the campaign,

strength of feelings about the election, and the amount of

knowledge participants felt they had about the platforms of

the candidates. Participants responded on 9-point rating

scales where higher numbers indicated a greater amount of

the construct. These three items were found to have acceptable interitem reliability ( = .80) and were thus averaged into

one involvement index.

Attitudes and feelings assessment. Prior attitudes

toward the upcoming election were assessed by having participants indicate their current position about the presidential election on a scale ranging from 4 (strongly favor

Clinton) to 0 (unsure or neither) to +4 (strongly favor Dole).

Two items assessed feelings toward the candidates, How do

you feel about Bill Clinton (Bob Dole) as a person? on scales

ranging from 4 (strongly dislike) to 0 (no feelings) to +4

(strongly like). After reverse scoring the feelings toward

Clinton measure, these three items were averaged into one

predebate attitude composite ( = .73), where negative numbers indicate more favorable attitudes and feelings toward

Clinton and positive numbers indicate more favorable attitudes and feelings toward Dole.

Expectancy assessment. Participants expectations

regarding the outcome of the debate were assessed with the

question Who do you think will win the debate? on a scale

ranging from 4 (definitely Clinton) to 0 (neither Clinton nor

Dole) to +4 (definitely Dole).

Postdebate Measures

Immediately following the debate, participants responded

to four sets of questions assessing (a) evaluations of the debate, (b) affective reactions to the debaters, (c) cognitive responses generated during the debate, and (d) postdebate political attitudes.

Evaluations of the debate. The first set of questions

assessed biased assimilation by measuring evaluations of the

debate itself. The first question was, In your opinion, who

won the debate? with a rating scale ranging from 4 (definitely Clinton) to 0 (neither Clinton nor Dole) to +4 (definitely Dole). The next two questions assessed the quality of

the arguments of the two debaters using the questions, How

strong were the arguments presented by Clinton (Dole)? and

How convincing was Clinton (Dole)? with rating scales

ranging from 1 (very weak/unconvincing) to 9 (very

strong/convincing).

Affective reactions. The third set of questions assessed

affective reactions to the two debaters, To what extent did listening to Clinton (Dole) make you feel? Participants responded to the items angry, irritated, happy, and

pleased on scales ranging from 1 (not at all) to 9 (very much).

Cognitive responses. Participants were asked to list

any thoughts or feelings you had while listening to the arguments of Clinton (Dole). After writing each thought or feeling, they indicated with the appropriate symbol whether the

thought or feeling was favorable (+), unfavorable (), or neutral (0) toward the argument.

Postdebate political attitudes. Participants responded

to several questions assessing the degree to which their political

attitudes had changed as a result of watching the debate. First, as

a measure of perceived attitude change, they rated how much

the arguments presented in the debate caused my opinion about

the presidential election to move on a scale ranging from 4

(strongly toward supporting Clinton) to 0 (no change) to +4

(strongly toward supporting Dole). A question that paralleled

BIASED ASSIMILATION OF SOCIOPOLITICAL ARGUMENTS

the predebate attitude assessment was also included. Participants rated their current positions about the presidential election

given the arguments presented in the debate.

19

haps reflecting public opinion of Clinton as a more gifted

communicator than Dole, participants reported expecting

that Clinton would probably win the debate (M = 1.63).

Bivariate correlations between the predebate measures are

also displayed in Table 1.1

Downloaded by [Laurentian University] at 19:01 22 April 2016

Follow-Up Measures

Beginning 1 week after the first debate, participants were

called by telephone and asked to answer several more questions regarding the debate. Of those who were contacted, all

agreed to participate. Sixty of the 70 participants present at

the debate were contacted. Those that were not contacted by

the day of the second 1996 Presidential Debate (October 16,

1996) were not called again.

During the follow-up telephone interview, participants responded to two sets of questions that were analogous to those

presented after the debate. First, they responded to several

questions assessing their evaluations of the debate, including

their opinion about who won the debate and the quality of the

arguments presented by each debater. Second, they were

again asked a set of political attitude questions assessing how

much they perceived their opinions to have changed because

of the debate and their current position regarding the election. No affective reactions or cognitive responses were obtained at the 1-week follow-up interview.

RESULTS

Overview of Analyses

There were three goals for organizing the data analyses.

First, a group of descriptive analyses was conducted with the

aim of providing a characterization of this sample regarding

opinions concerning the presidential election. Second, regression analyses were conducted to determine whether responses to the predebate measures predicted postdebate reactions. Third, a group of mediational regression analyses was

conducted to examine the role of affective reactions during

the debate as potentially important components of any effect

of the predebate measures on postdebate reactions.

Descriptive Analyses

Descriptive analyses conducted on the predebate measures

indicated that the distributions did not deviate greatly from

the assumptions of normality. As can be seen in Table 1,

participants as a group scored near the midpoint of the

scales measuring whether they would have watched the debate (M = 3.54) and their involvement in the election (M =

4.74). The predebate attitude index reflected the United

States voting population in that Clinton was rated more favorably and liked more than Dole (M = 0.91). Also, per-

Association of Predebate With Immediate

Postdebate and Follow-Up Measures

To assess the association between the predebate and

postdebate measures, multiple regression analyses were

conducted. For each postdebate variable, the four predebate

variables (watch, involvement, predebate attitude, and expectancy) were simultaneously entered as predictor variables. There are two effects in particular that bear special

mention. First, the biased assimilation effect would be supported if predebate attitude significantly predicts evaluations of the debate. Second, the disconfirmed expectancies

argument would be supported if expectancy significantly

predicts evaluations of the debate. The disconfirmed expectancies argument suggests that those in favor of Clinton, for

example, expect Clinton to win and any information that

disconfirms this expectation (pro-Dole or anti-Clinton arguments) is processed more deeply and evaluated more critically than information that confirms the expectation

(pro-Clinton or anti-Dole arguments). The other two variables were included in the analyses to determine whether

ones involvement in the election or likelihood of watching

the debate might predict postdebate measures in a way that

would clarify the debate evaluation process.2

Biased assimilation. Biased assimilation was assessed by examining responses to the debate evaluation measures. First, the question assessing which candidate partici-

1Several of the predebate measures were correlated. Most notably, the

predebate attitude index is positively correlated with the expectation measure

(r = .39). No attempt to combine the expectation measure with the predebate

attitude index was made, however, because of the important theoretical distinction between the two constructs. Furthermore, collinearity diagnostics

indicated that collinearity among the predebate measures was not a problem

for the subsequently presented regression analyses. Tolerance values were

always .74 or higher, and the variance inflation factor never exceeded 1.35.

2In addition, hierarchical regression analyses with the interactions between the predebate measures entered as a second step were conducted.

These analyses were specifically aimed at exploring any interactions involving the involvement variable. Given that past research suggests that

attitude strength moderates biased assimilation (Pomerantz, Chaiken, &

Tordesillas, 1995), it seemed reasonable to test for the possibility that

predebate attitudes bias participants evaluations of the debate only for

people with strong involvement in the presidential campaign. However, no

significant interactions were revealed. The hierarchical regressions and

variable interactions will not be discussed.

Downloaded by [Laurentian University] at 19:01 22 April 2016

20

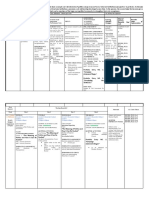

TABLE1

Means, Standard Deviations, and Pearsons Correlations of Predebate, Postdebate, and Follow-Up Measures

Measures

Predebate measures

1. Watch

2. Involvement

3. Attitude

4. Expectancy

Postdebate measures

5. Perceived winner

6. Quality index

7. Positive affect

8. Negative affect

9. Positive cognitive responses

10. Negative cognitive responses

11. Perceived attitude change

12. Actual attitude change

Follow-up measures

14. Perceived winner

15. Quality index

16. Perceived attitude change

17. Actual attitude change

ap

< .05. bp < .01.

SD

3.54

4.74

0.91

1.63

1.18

2.06

1.76

1.36

.41b

.04

.18

.27a

.10

.39b

1.26

1.82

1.11

2.37

1.26

1.26

0.16

0.33

2.43

3.52

4.20

3.83

2.92

2.87

2.43

1.56

.31

.28a

.34b

.29a

.10

.15

.17

.13

.53b

.59b

.68b

.72b

.61b

.58b

.50b

.07

0.90

1.33

0.10

0.00

2.23

3.57

2.21

1.68

.28a

.28a

.11

.13

.61b

.61b

.41b

.03

.09

.13

.11

.03

.12

.08

.10

.12

.07

.07

.28a

.26a

10

11

12

.28a

.21

.24a

.25a

.28a

.26a

.01

.05

.79b

.81b

.75b

.69b

.57b

.57b

.54b

.76b

.78b

.76b

.63b

.49b

.50b

.86b

.73b

.63b

.59b

.56b

.72b

.62b

.53b

.48b

.83b

.65b

.50b

.59b

.43b

.33b

.30a

.23

.06

.05

.79b

.83b

.41b

.50b

.76b

.83b

.43b

.39b

.83b

.80b

.59b

.50b

.67b

.75b

.50b

.41b

.66b

.72b

.53b

.35b

.60b

.60b

.42b

.24

.57b

.60b

.49b

.19

.44b

.47b

.40b

.65b

13

14

15

16

.81b

.56b

.38b

.54b

.46b

.38b

Downloaded by [Laurentian University] at 19:01 22 April 2016

BIASED ASSIMILATION OF SOCIOPOLITICAL ARGUMENTS

pants thought won the debate (perceived winner) was

examined. Second, a Clinton quality index and a Dole quality

index were created by averaging responses to the questions

assessing ratings of the strength of the arguments and convincingness of each debater, Clinton r(70) = .78, p < .001; Dole

r(70) = .69, p < .001. In accordance with past research (Lord

et al., 1979; Munro & Ditto, 1997), these two indexes were

then combined into a quality index difference score by subtracting the Clinton quality index from the Dole quality index.

For both of the biased assimilation measures, predebate

attitude was the only significant predictor (perceived winner: = .46, t[69] = 3.98, p < .001; quality index difference

score: = .57, t[69] = 5.15, p < .001).3 A summary of the

regression analyses can be found in Table 2. Those who

held more favorable predebate attitudes and feelings toward

Dole were more likely to have perceived Dole to have won

the debate and rated the arguments of Dole more favorably

relative to the arguments of Clinton. Supporting the biased

assimilation effect, prior attitudes bias participants

postdebate ratings of who won the debate and their evaluations of the arguments presented during the debate. On the

other hand, the disconfirmed expectancies argument was

not supported as expectancy did not uniquely predict evaluations of the debate.

Affect. Affective reactions to the two debaters were examined by creating two factors out of the four affect items.

The items happy and pleased were highly correlated

(Clinton: r[70] = .84, p < .001; Dole: r[70] = .83, p < .001) and

were thus averaged into a positive affect index. Similarly, the

items angry and irritated (Clinton: r[70] = .73, p < .001;

Dole: r[70] = .81, p < .001) were averaged into a negative affect index. Affect difference scores were created by subtracting each of the two Clinton affect factors from the corresponding Dole affect factors.

For both affect difference scores, predebate attitude was

the only significant predictor (positive: = .66, t[69] =

6.65, p < .001; negative: = .71, t[69] = 7.42, p < .001).

These analyses indicate that those who held more favorable

prior attitudes and feelings toward Dole reported more positive and less negative affect in response to Dole relative to

Clinton. A regression summary table can be found in the

top half of Table 3.

Biased cognitive elaboration. Biased cognitive elaboration was assessed by examining self-coded positive and

negative cognitive responses generated toward each debater.

3In addition, the Clinton quality index and the Dole quality index were an-

alyzed independently. The results were identical to those of the perceived

winner measure and quality index difference scoreonly predebate attitude

was a significant predictor.

21

Positive and negative cognitive response difference scores

were created by subtracting each type of response generated

after listening to Clinton from each type of response generated after listening to Dole.4

For both cognitive response difference scores, predebate

attitude was a significant predictor (positive: = .62, t[69] =

5.77, p < .001; negative: = .58, t[69] = 5.11, p < .001).

Those who held more favorable prior attitudes and feelings

toward Dole reported more positive and less negative

cognitions in response to Dole relative to Clinton. In addition, for the positive cognitive response difference score, ratings of the likelihood that participants would have watched

the debate was a significant predictor, = .23, t(69) = 2.10, p

< .05. Those who reported a greater likelihood that they

would have watched the debate reported more positive and

less negative cognitions in response to Clinton relative to

Dole. A summary of the regression analyses can be found in

the bottom half of Table 3.

Attitude change. In practical terms, the most important measures assessing the actual effects of the debate on

viewers political opinions were those measuring attitude

change. The first attitude change measure was the degree to

which participants perceived their opinion to have moved as

a result of the debate (perceived attitude change). Predebate

attitude was the only significant predictor of perceived attitude change, = .59, t(68) = 5.02, p < .001.5 Those who held

more favorable prior attitudes toward Dole were more likely

to have perceived their postdebate attitudes as having

moved in the direction of Dole. The perceived attitude

change measure can be contrasted with an actual attitude

change measure created by subtracting responses to the

postdebate measure from responses to the predebate measure of participants current attitudes toward the election.

The regression analysis on the actual attitude change measure revealed no significant predictors (see Table 4 for a

summary).

One-week follow-up measures. The follow-up measures were submitted to the same analyses as reported earlier

with one exception. For each follow-up measure the analogous immediate postdebate measure was entered as a predictor variable in addition to the four predebate measures. For

example, for the follow-up measure assessing perceived winner, the predebate measures watch, involvement, predebate

attitude, and expectancy as well as the immediate postdebate

4A neutral cognitive response difference score was also created and analyzed, revealing no significant effects. It will not be further discussed.

5The inconsistent degrees of freedom for all analyses involving the immediate postdebate measure assessing perceived attitude change are a result of the choice of one participant not to answer that question.

22

MUNRO ET AL.

TABLE 2

Summary of Regression Analyses for Immediate Postdebate (and Follow-Up) Biased Assimilation Measures

B

SE B

0.98 (0.22)

0.63 (0.35)

0.17 (0.07)

0.18 (0.06)

0.13 (0.07)

(0.59)

1.70 (1.17)

0.16 (0.12)

0.20 (0.14)

0.14 (0.10)

0.24 (0.17)

(0.08)

.46** (.28**)

.10 (.04)

.15 (.05)

.06 (.03)

(.63**)

7.05 (0.66)

1.13 (0.30)

0.01 (0.07)

0.15 (0.12)

0.36 (0.05)

(0.76)

2.37 (1.93)

0.22 (0.20)

0.28 (0.22)

0.19 (0.15)

0.33 (0.26)

(0.10)

.57** (.15)

.01 (.03)

.09 (.07)

.12 (.02)

(.72**)

Dependent Variables and Predictor Variables

Downloaded by [Laurentian University] at 19:01 22 April 2016

Immediate postdebate (follow-up) perceived winner

Constant

Predebate attitude

Expectancy

Involvement

Watch

Perceived winner

Immediate postdebate (follow-up) quality index difference score

Constant

Predebate attitude

Expectancy

Involvement

Watch

Quality index difference score

Note. Numbers in parentheses indicate follow-up analyses. Immediate postdebate perceived winner: R2 = .32, MSerror = 4.24;

follow-up perceived winner: R2 = .69, MSerror = 1.67. Immediate postdebate quality index difference score: R2 = .38, MSerror = 8.21;

follow-up quality index difference score: R2 = .71, MSerror = 4.05 (ps < .001).

*p < .05. **p < .01.

TABLE 3

Summary of Regression Analyses for Affect and Cognitive Response Measures

Dependent Variables and Predictor Variables

Positive (negative) affect difference score

Constant

Predebate attitude

Expectancy

Involvement

Watch

Positive (negative) cognitive response difference score

Constant

Predebate attitude

Expectancy

Involvement

Watch

SE B

7.07 (7.54)

1.57 (1.54)

0.05 (0.10)

0.27 (0.19)

0.28 (0.03)

2.52 (2.23)

0.24 (0.21)

0.30 (0.26)

0.21 (0.18)

0.36 (0.31)

.66** (.71**)

.02 (.04)

.13 (.10)

.08 (.01)

9.27 (7.20)

1.02 (0.94)

0.22 (0.13)

0.24 (0.10)

0.56 (0.34)

1.91 (1.98)

0.18 (0.18)

0.23 (0.23)

0.16 (0.16)

0.27 (0.28)

.62** (.58**)

.10 (.06)

.17 (.07)

.23* (.14)

Note. Numbers in parentheses indicate negative affect or negative cognitive responses analyses. Positive affect difference score: R2

= .50, MSerror = 9.40; negative affect difference score: R2 = .53, MSerror = 7.29; positive cognitive response difference score: R2 = .41,

MSerror = 5.32; negative cognitive response difference score: R2 = .35, MSerror = 5.72 (ps < .001).

*p < .05. **p < .01.

measure assessing perceived winner were all entered simultaneously as predictor variables. If the predebate attitude index

does not significantly predict the follow-up measure, then it

would suggest that predebate attitude does not have any additional effect during the 1-week delay. If the predebate attitude

index does significantly predict the follow-up measure, then

it would suggest that predebate attitude does have an additional effect on the follow-up measure over and above the immediate postdebate effect. If another predebate measure significantly predicts the follow-up measure, then it would

suggest that a delayed effect is present that does not appear

until after the immediate postdebate assessment.

The two biased assimilation measures revealed somewhat inconsistent findings. On both measures, the analogous immediate postdebate measures were significant

predictors (perceived winner: = .63, t[59] = 7.15, p <

.001; quality index difference score: = .72, t[59] = 7.55, p

< .001). In addition, predebate attitude was a significant

predictor on the perceived winner measure, = .28, t(59) =

3.05, p < .01. However, neither predebate attitude nor any

other predebate measure was a significant predictor on the

quality index difference score, = .15, t(59) = 1.46, p < .15

(see Table 2 for a summary). Therefore, for each measure,

the strong positive correlation between the follow-up mea-

BIASED ASSIMILATION OF SOCIOPOLITICAL ARGUMENTS

23

TABLE 4

Summary of Regression Analyses for Immediate Postdebate (and Follow-Up) Attitude Change Measures

Dependent Variables and Predictor Variables

Downloaded by [Laurentian University] at 19:01 22 April 2016

Immediate postdebate (follow-up) perceived attitude change

Constant

Predebate attitude

Expectancy

Involvement

Watch

Perceived attitude change

Immediate postdebate (follow-up) actual attitude change

Constant

Predebate attitude

Expectancy

Involvement

Watch

Actual attitude change

SE B

2.28 (0.77)

0.81 (0.40)

0.40 (0.05)

0.00 (0.14)

0.17 (0.63)

(0.30)

1.73 (1.67)

0.16 (0.17)

0.21 (0.21)

0.14 (0.14)

0.24 (0.24)

(0.12)

.59** (.33*)

.22 (.03)

.00 (.13)

.08 (.34*)

(.32*)

0.35 (1.64)

0.07 (0.01)

0.09 (0.17)

0.07 (0.03)

0.10 (0.35)

(0.69)

1.31 (1.13)

0.12 (0.10)

0.16 (0.14)

0.11 (0.09)

0.18 (0.16)

(0.10)

.08 (.01)

.08 (.14)

.09 (.04)

.08 (.25*)

(.65**)

Note. Numbers in parentheses indicate follow-up analyses. Immediate postdebate perceived attitude change: R2 = .31,

MSerror = 4.36; follow-up perceived attitude change: R2 = .37, MSerror = 3.37 (ps < .001). Immediate postdebate actual

attitude change: R2 = .03, MSerror = 2.50 (p = .73); follow-up actual attitude change: R2 = .49, MSerror = 1.58 (p < .001).

*p < .05. **p < .01.

sure and its analogous immediate postdebate measure suggests that the biased assimilation effect remains after 1

week. Furthermore, the perceived winner measure revealed

predebate attitude to be a significant predictor over and

above the predictive power of the analogous immediate

postdebate measure. This suggests modest support for a

longer lasting effect of predebate attitude on evaluationsa

bias that continues to occur even beyond the immediate reactions to the debate information.

The attitude change measures also revealed inconsistent

findings with regard to the predictive value of predebate attitude. For both the perceived attitude change and actual attitude change measures, the analogous immediate

postdebate measures were significant predictors (perceived

attitude change: = .32, t[58] = 2.53, p < .02; actual attitude change: = .65, t[59] = 6.58, p < .001). In addition,

the likelihood that the participant would have watched the

debate measure was a significant predictor for both attitude

change measures (perceived attitude change: = .34, t[58]

= 2.65, p < .02; actual attitude change: = .25, t[59] =

2.18, p < .001). These findings indicate that those who reported being less likely to watch the debate perceived their

attitudes to have changed in the direction of Dole 1 week

after the debate and their attitudes did change in the direction of Dole (as assessed by the prepost measure of actual

attitude change). Because this variable was not associated

with the attitude change measures immediately after the debate, these effects represent a delayed effect. Finally,

predebate attitude was a significant predictor of perceived

attitude change, = .33, t(58) = 2.33, p < .03 (see Table 4

for a summary). This indicates that those who had more favorable predebate attitudes and feelings toward Clinton

(Dole) perceived their attitudes to have moved in the direction of Clinton (Dole) 1 week after the debate. Again, this

effect of prior attitude on perceived attitude change 1 week

after the debate represents a continued change over and

above that explained by the analogous immediate

postdebate measure.

The Underlying Mechanisms of Biased

Assimilation

The analyses presented thus far establish that (a) prior attitudes are associated with evaluative reactions to the debate

arguments and (b) expectancies are not uniquely associated

with evaluative reactions to the debate arguments. The next

goal of the analyses was to investigate the role of both positive and negative affect as possible mediating factors.

Those in favor of Clinton, for example, may have negative

affective reactions to any information attacking Clinton or

supporting Dole, thus motivating those individuals to negatively evaluate that information in comparison to information supporting Clinton or attacking Dole. If this affective

account of biased assimilation were true, positive and negative affect would mediate the link between prior attitudes

and debate evaluations.

To conduct the mediational regression analyses, the recommendations put forth by Baron and Kenny (1986) were

followed. Three regression equations were created for each

potential mediator. First, the immediate postdebate quality

index difference score (the most widely used measure of biased assimilation) was regressed on predebate attitude.

Predebate attitude significantly predicted the quality index

difference score, = .59, t(69) = 5.99, p < .001.

Second, the potential mediators (positive and negative affect difference scores) were regressed on predebate attitude

in two separate analyses. Predebate attitude significantly pre-

Downloaded by [Laurentian University] at 19:01 22 April 2016

24

MUNRO ET AL.

dicted both positive and negative affect difference scores.

The more favorable prior attitudes were toward Dole, the

more positive affect was reported in response to Dole relative

to Clinton, = .68, t(69) = 7.71, p < .001; and the more negative affect was reported in response to Clinton relative to

Dole, = .72, t(69) = 8.59, p < .001.

Third and most important, the biased assimilation measure was simultaneously regressed on the potential mediators

and predebate attitude. Predebate attitude no longer significantly predicted quality index difference scores for either the

analysis assessing positive affect as the potential mediator (

= .14, t[69] = 1.25, p = .22) or the analysis assessing negative

affect as the potential mediator ( = .06, t[69] = 0.51, p =

.62). In contrast, both of the potential mediators remained

significant predictors of quality index difference scores (positive affect: = .66, t[69] = 6.11, p < .001; negative affect:

= .74, t[69] = 6.67, p < .001).6

To assess the role of affect as a potential mediator of biased cognitive elaboration, the same strategy was repeated

in four separate mediational analyses using positive and

negative affect difference scores as potential mediators between predebate attitude and positive and negative cognitive response difference scores. Predebate attitude

significantly predicted both the positive and negative cognitive response difference scores (positive: = .60, t[69] =

6.25, p < .001; negative: = .58, t[69] = 5.80, p < .001).

As reported previously, predebate attitude significantly predicted both potential mediators, positive and negative affect

difference scores. Finally, when each dependent variable

was simultaneously regressed on predebate attitude and the

potential mediators, positive and negative affect were significant predictors (all || > .54 and p values < .01),

whereas predebate attitude was not (all || < .13 and p values > .05). In total, the mediational analyses indicate that

the positive and negative affect difference scores meet the

criteria of true mediators (Baron & Kenny, 1986) between

predebate attitude and biased evaluations and cognitive

elaborations of the debate.

DISCUSSION

Considering the importance of the U.S. Presidential Election,

it is comforting to believe that presidential debates sway

some significant portion of the voting public toward the candidate with the stronger political arguments. The results of

6The mediational analyses were repeated several times using perceived

winner, the Clinton quality index, and the Dole quality index as dependent

variables in the place of the quality index difference score. The results were

virtually identical to those reported for the quality index difference score in

that both positive and negative affect difference scores were found to be true

mediators between predebate attitude and whichever measure of biased assimilation was used as the dependent variable.

this research paint a somewhat less idealistic picture. First,

people seem to process the arguments in a biased manner by

evaluating the reasoning of their predebate favored candidate

more positively than that of their predebate opposed candidate. Second, rather than being a rational analysis of the logical arguments presented in the debate, debate evaluations can

hinge more on peoples affective responses to the debater.

Each of the major findings and the significance of the findings in terms of past research and theory are discussed next.

Biased Assimilation

Supporting a host of laboratory studies, this research demonstrates that the biased assimilation effect can be found in a

setting involving the presentation of naturally occurring information not specifically constructed to reveal the phenomenon. The regression analyses consistently showed that participants viewing the first 1996 U.S. Presidential Debate did

indeed undergo a biased assimilation of the arguments presented in the debate such that arguments confirming prior attitudes were rated more positively than arguments

disconfirming prior attitudes. Rather than evaluating the arguments in a fair and objective manner based on their logical

validity, our prior attitudes bias the manner in which we evaluate the arguments leading us to favor those arguments that

support the prior attitudes.

Furthermore, not only did prior attitudes predict argument

evaluations and the perceived winner immediately after the

debate, but also the immediate postdebate measures predicted the analogous follow-up measures. These results suggest that biased assimilation is not a transient reaction to

carefully constructed laboratory materials that disappears

shortly after the presentation of those materials. On the contrary, there was some support for the possibility that prior attitudes not only have an immediate effect on judgments of

the perceived winner but also a delayed effect. Although we

did not collect data on participants postdebate exposure to

media commentary, one could speculate that this delayed effect is a result of participants assimilation of any media

commentary viewed during the period between the end of the

experimental session and the follow-up questioning.

One question that remains unanswered is the question of

symmetry. Although the regression analyses revealed that

the biased assimilation effect was significant for the entire

sample, the inability to easily determine the objective winner

of the debate precludes us from knowing whether or not a

subset of unbiased participants exists. It is entirely possible

that a truly objective analysis of the arguments would reveal

Clinton (or Dole) to be the consensus winner. If so, one could

make the argument that those who favored Clinton (or Dole)

prior to the debate are actually not displaying the biased assimilation effect. Without being able to objectively determine the outcome of the debate, the symmetry and strength

of the bias in the face of unbalanced information remains hidden. Future research could address this important question by

BIASED ASSIMILATION OF SOCIOPOLITICAL ARGUMENTS

varying the objective quality of the arguments on either side

of the debate. An argument quality manipulation could effectively assess the symmetry and strength of the biased assimilation effect by determining how much, if it all, argument

quality moderates biased assimilation.

Downloaded by [Laurentian University] at 19:01 22 April 2016

Affect and the Evaluation of Sociopolitical

Arguments

It is not difficult to recall instances of political discussions

ending in heated arguments and damaged relationships.

Sociopolitical positions on subjects like abortion rights, tax

increases, and welfare seem to be able to turn up the fire underneath people. This is true both in the pleasing feeling of

knowing your position has been validated by others and the

unease that arises when your position is being attacked. This

research empirically supports the conjecture that

sociopolitical arguments are processed in a less than purely

rational, logical manner by indicating that the evaluation of

sociopolitical arguments is strongly associated with affect.

First, predebate attitude, a composite of participants current positions regarding the election and their feelings toward the two candidates, uniquely and significantly

predicted each of the postdebate evaluation measures. People

seem to have difficulty dissociating their feelings toward the

candidates not only from their positions regarding the election (Abelson et al., 1982) but also from their evaluations of

the information presented by the candidates. If we hold positive feelings toward a presidential candidate, we also tend to

rate their arguments positively. On the other hand, negative

feelings toward a candidate are associated with negative argument evaluations. Although the predebate attitude composite consistently predicted debate evaluations, the

expectancy measure consistently failed to uniquely predict

debate evaluations. Therefore, no support for the

disconfirmed expectancies account of biased assimilation

was found in this research. It should be noted, however, that

expectancy and predebate attitude were significantly correlated. Future research could be aimed at investigating the nature of this relation.

Second, differential affective reactions to the favored and

opposed candidate were shown to mediate the link between

prior attitudes and peoples evaluations and cognitive elaborations of the arguments of the debaters. The desire to perceive the arguments as being supportive of the attitude may

create specific affective reactions when the arguments are

initially perceived as being unsupportive. These emotions

then influence the manner in which the arguments are processed. Attitude-disconfirming arguments produce increased

negative and decreased positive affect leading people to generate a greater number of negative and fewer positive

cognitions on the way toward more negative overall evaluations of the arguments. Attitude-confirming arguments, on

the other hand, produce increased positive and decreased

negative affect, more positive and fewer negative cognitions,

25

and more positive overall evaluations of the arguments.

Mediational analyses are, of course, not a substitute for

well-controlled experimental research demonstrating a

causal role for affect, but they do suggest that the data are

consistent with the affective-motivational account (Munro &

Ditto, 1997).

Attitude Change in Reactions to

Sociopolitical Debates

Although there is a bias to more positively evaluate ones

predebate favorite, this does not necessarily influence opinions. In support of past research (Miller et al., 1993; Munro

& Ditto, 1997), opinion change in the form of polarization

was found for the measure of participants perceived attitude

change, whereas no opinion change was found for the measure of actual attitude change. Of course the actual attitude

change measure is limited in its assessment of polarization

because of the possibility of ceiling and floor effects (Lord et

al., 1979; Miller et al.). Those with strong predebate attitudes

toward the candidates would be constrained by the scale

from reporting a more extreme attitude after the debate.

Given these findings, this research suggests at the least that

sociopolitical debates produce no change in the opinion of

viewers as a group and at the most that debates reinforce peoples predebate opinions.

Conclusions

This research suggests that viewers of major sociopolitical

debates like those between the democratic and republican

candidates for U.S. president are biased by their predebate

feelings and attitudes toward the candidates and the emotional reactions that ensue. However, the 1996 presidential

campaign featured an incumbent seeking re-election during

times of economic prosperity. Therefore, viewers may have

been less motivated to think deeply about the arguments

(Petty & Cacioppo, 1986) than they might have been under a

period of economic crisis. Similarly, data were collected

from college students who because of their generational or

developmental cohort may be less willing or able to critically

analyze political information. Instead, they may have relied

on superficial characteristics like their feelings toward the

candidates. Therefore, it would be premature to suggest that

debates never lead viewers to change their opinions to the

candidate with the stronger logical arguments. Still, although

the circumstances surrounding future debates might create

very different reactions, one also has to wonder whether televised media images, sound-bites, and political spin-doctoring havent tipped the scales toward more superficial and

emotional responding at the expense of thorough and

thoughtful analysis. Ultimately, this research poses the question of whether or not the ideal function of public debatesto provoke a thoughtful analysis of opposing argumentsmight not be better served.

26

MUNRO ET AL.

Downloaded by [Laurentian University] at 19:01 22 April 2016

REFERENCES

Abelson, R. P., Kinder, D. R., Peters, M. D., & Fiske, S. T. (1982). Affective

and semantic components in political person perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42, 619630.

Anderson, C. A., Lepper, M. R., & Ross, L. (1980). Perseverance of social

theories: The role of explanation in the persistence of discredited information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 10371049.

Aronson, E. (1989). Analysis, synthesis, and the treasuring of the old. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 15, 508512.

Aronson, E. (1992). The return of the repressed: Dissonance theory makes a

comeback. Psychological Inquiry, 3, 303311.

Asch, S. E. (1946). Forming impressions of personality. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 41, 12301240.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderatormediator distinction in

social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51,

11731182.

Berkowitz, L., & Devine, P. G. (1989). Research traditions, analysis, and

synthesis in social psychological theory: The case of dissonance theory.

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 15, 493507.

Bothwell, R. K., & Brigham, J. C. (1983). Selective evaluation and recall

during the 1980 ReaganCarter debate. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 13, 427442.

Cervone, D., & Peake, P. (1986). Anchoring, efficacy, and action: The influence of judgmental heuristics on self-efficacy judgments and behavior.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 492501.

Darley, J. M., & Gross, R. H. (1983). A hypothesis confirming bias in labeling effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 2033.

Davis, M. H. (1982). Voting intentions and the 1980 CarterReagan debate.

Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 12, 481492.

Duncan, S. L. (1976). Differential social perception and attribution of intergroup violence: Testing the lower limits of stereotyping of Blacks. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34, 590598.

Edwards, K., & Smith, E. E. (1996). A disconfirmation bias in the evaluation

of arguments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 524.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Hamilton, D. L., & Rose, T. L. (1980). Illusory correlation and the maintenance of stereotypic beliefs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 832845.

Hastorf, A., & Cantril, H. (1954). They saw a game: A case study. Journal of

Abnormal and Social Psychology, 49, 129134.

Jelalian, E., & Miller, A. G. (1984). The perseverance of beliefs: Conceptual

perspectives and research developments. Journal of Social and Clinical

Psychology, 2, 2556.

Jones, E. E., Rock, L., Shaver, K. G., Goethals, G. R., & Ward, L. M. (1968).

Pattern of performance and ability attribution: An unexpected primacy effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 10, 317340.

Katz, E., & Feldman, J. J. (1962). The debates in the light of research: A survey of surveys. In S. Kraus (Ed.), The great debates (pp. 173223).

Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Kinder, D. R., & Sears, D. O. (1985). Public opinion and political action. In

G. Lindzey & E. Aronson (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (3rd

ed., pp. 659741) New York: Random House.

Langer, E. J., & Roth, J. (1975). Heads I win, tails its chance: The illusion of

control as a function of the sequence of outcomes in a purely chance task.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32, 951955.

Lanoue, D. J. (1992). One that made a difference: Cognitive consistency, political knowledge, and the 1980 presidential debate. Public Opinion

Quarterly, 56, 168184.

Lord, C. G. (1989). The disappearance of dissonance in an age of relativism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 15, 513518.

Lord, C. G. (1992). Was cognitive dissonance theory a mistake? Psychological Inquiry, 3, 339342.

Lord, C. G., Ross, L., & Lepper, M. R. (1979). Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37,

20982109.

McAndrew, F. T. (1981). Pattern of performance and attributions of ability

and gender. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 7, 583587.

McHoskey, J. W. (1995). Case closed? On the John F. Kennedy assassination: Biased assimilation of evidence and attitude polarization. Basic and

Applied Social Psychology, 17, 395409.

Merton, R. K. (1957). Social theory and social structure. New York: Free

Press.

Miller, A. G., McHoskey, J. W., Bane, C. M., & Dowd, T. G. (1993). The attitude polarization phenomenon: Role of response measure, attitude extremity, and behavioral consequences of reported attitude change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 561574.

Munro, G. D., & Ditto, P. H. (1997). Biased assimilation, attitude polarization, and affect in reactions to stereotype-relevant scientific information.

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 636653.

Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of

persuasion. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology, (Vol. 19, pp. 123205). New York: Academic.

Plous, S. (1989). Thinking the unthinkable: The effects of anchoring on likelihood estimates of nuclear war. Journal of Applied Social Psychology,

19, 6791.

Plous, S. (1991). Biases in the assimilation of technological breakdowns: Do

accidents make us safer? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 21,

10581082.

Pomerantz, E. M., Chaiken, S., & Tordesillas, R. S. (1995). Attitude strength

and resistance processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

69, 408419.

Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. F. (1968). Pygmalion in the classroom. New

York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Ross, L., Lepper, M. R., & Hubbard, M. (1975). Perseverance in self-perception and social perception. Biased attribution processes in the debriefing

paradigm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32, 880892.

Sears, D. O., & Chaffee, S. H. (1979). Uses and effects of the 1976 debates: An

overview of empirical studies. In S. Kraus (Ed.), The great debates, 1976:

Ford vs. Carter (pp. 223261). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Sigelman, L., & Sigelman, C. K. (1984). Judgments of the CarterReagan debate: The eyes of the beholders. Public Opinion Quarterly, 48, 624628.

Slovic, P., & Lichtenstein, S. (1971). Comparison of Bayesian and regression

approaches to the study of information processing in judgment. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 6, 649744.

Snyder, M., & Swann, W. B., Jr. (1978). Behavioral confirmation in social interaction: From social perception to social reality. Journal of Experimental

Social Psychology, 14, 148162.

Snyder, M., & Uranowitz, S. W. (1978). Reconstructing the past: Some cognitive consequences of person perception. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 36, 941950.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty:

Heuristics and biases. Science, 185, 11241131.

von Hippel, W., Sekaquaptewa, D., & Vargas, P. (1995). On the role of encoding processes in stereotype maintenance. Advances in Experimental

Social Psychology, 27, 177254.

Word, C. O., Zanna, M. P., & Cooper, J. (1974). The nonverbal mediation of

self-fulfilling prophecies in interracial interaction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 10, 109120.

Zuwerink, J. R., & Devine, P. G. (1996). Attitude importance and resistance

to persuasion: Its not just the thought that counts. Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology, 70, 931944.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Public Perceptions of Bhutan's Approach To Sustainable Development in PracticeDocument17 pagesPublic Perceptions of Bhutan's Approach To Sustainable Development in PracticeintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- Public Perceptions and Attitudes Towards An Established Managed Realignment Scheme: Orplands, Essex, UKDocument9 pagesPublic Perceptions and Attitudes Towards An Established Managed Realignment Scheme: Orplands, Essex, UKintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- Emotions in Conflicts: Understanding Emotional Processes Sheds Light On The Nature and Potential Resolution of Intractable ConflictsDocument5 pagesEmotions in Conflicts: Understanding Emotional Processes Sheds Light On The Nature and Potential Resolution of Intractable ConflictsintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- Non-State Actors in Ungoverned Spaces and Cyber ResponsibilityDocument20 pagesNon-State Actors in Ungoverned Spaces and Cyber ResponsibilityintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- A Methodology For A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Community Groups' Attitudes, Perceptions and Use of DrugsDocument5 pagesA Methodology For A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Community Groups' Attitudes, Perceptions and Use of DrugsintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- Paul Cairney - Complexity Theory in Political Science and Public PolicyDocument13 pagesPaul Cairney - Complexity Theory in Political Science and Public PolicyintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- Conceptualising Climate Change in Rural Australia: Community Perceptions, Attitudes and (In) ActionsDocument12 pagesConceptualising Climate Change in Rural Australia: Community Perceptions, Attitudes and (In) ActionsintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- Public Perceptions of Termite Control Practices in Several Ontario (Canada) MunicipalitiesDocument8 pagesPublic Perceptions of Termite Control Practices in Several Ontario (Canada) MunicipalitiesintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- Perceptions and Attitudes Towards Gas Flaring in The Niger Delta, NigeriaDocument9 pagesPerceptions and Attitudes Towards Gas Flaring in The Niger Delta, NigeriaintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- Attitudes, Knowledge, Risk Perceptions and Decision-Making Among Women With BreastDocument18 pagesAttitudes, Knowledge, Risk Perceptions and Decision-Making Among Women With BreastintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- Humiliation and The Inertia Eff Ect: Implications For Understanding Violence and Compromise in Intractable Intergroup Confl IctsDocument15 pagesHumiliation and The Inertia Eff Ect: Implications For Understanding Violence and Compromise in Intractable Intergroup Confl IctsintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- Enclaves of Banditry: Ungoverned Forest Spaces and Cattle Rustling in Northern NigeriaDocument24 pagesEnclaves of Banditry: Ungoverned Forest Spaces and Cattle Rustling in Northern NigeriaintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding Causes of War and PeaceDocument28 pagesUnderstanding Causes of War and PeaceintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- Toward An International Law For Ungoverned Spaces: The Global ForumDocument8 pagesToward An International Law For Ungoverned Spaces: The Global ForumintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- Studying Political Settlements in AfricaDocument18 pagesStudying Political Settlements in AfricaintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- Jack A. Goldstone - Initial Conditions, General Laws, Path Dependence, and Explanation in Historical SociologyDocument18 pagesJack A. Goldstone - Initial Conditions, General Laws, Path Dependence, and Explanation in Historical SociologyintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- The Impact of Conflict and Fragility On HouseholdsDocument20 pagesThe Impact of Conflict and Fragility On HouseholdsintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- Maria Krysan, Amanda E. Lewis - The Changing Terrain of Race and Ethnicity-Russell Sage Foundation (2006)Document288 pagesMaria Krysan, Amanda E. Lewis - The Changing Terrain of Race and Ethnicity-Russell Sage Foundation (2006)intemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- Ian Greener - The Potential of Path Dependence in Political Studies PDFDocument11 pagesIan Greener - The Potential of Path Dependence in Political Studies PDFintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- Legal Pluralism in Theory and Practice: Analytical EssayDocument25 pagesLegal Pluralism in Theory and Practice: Analytical EssayintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- Hoang, K. K. - Book Review - The Politics of Trafficking - The First International Movement To Combat The Sexual Exploitation ofDocument3 pagesHoang, K. K. - Book Review - The Politics of Trafficking - The First International Movement To Combat The Sexual Exploitation ofintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- Studying Political Settlements in AfricaDocument18 pagesStudying Political Settlements in AfricaintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- Guo-Ping He, Hou-Qing Luo-The Drawbacks and Reform of China's Current Rural Land System - An Analysis Based On Contract, Property Rights and Resource AllocationDocument18 pagesGuo-Ping He, Hou-Qing Luo-The Drawbacks and Reform of China's Current Rural Land System - An Analysis Based On Contract, Property Rights and Resource AllocationintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- The Impact of Conflict and Fragility On HouseholdsDocument20 pagesThe Impact of Conflict and Fragility On HouseholdsintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- Free Trade A Mountain Road and The Right To Protest European Economic Freedoms and Fundamental Individual RightsDocument11 pagesFree Trade A Mountain Road and The Right To Protest European Economic Freedoms and Fundamental Individual RightsintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- Laurence J. O'Toole JR - The Theory-Practice Issue in Policy Implementation ResearchDocument21 pagesLaurence J. O'Toole JR - The Theory-Practice Issue in Policy Implementation ResearchintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- Assessing Farmers' Willingness To Accept "Greening"Document23 pagesAssessing Farmers' Willingness To Accept "Greening"intemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- Kelloway, E. Kevin Using Mplus For Structural Equation Modeling A Researchers GuideDocument250 pagesKelloway, E. Kevin Using Mplus For Structural Equation Modeling A Researchers Guideintemperante100% (4)

- Takehiko Uemura, People's Participation Environment-Sustainable Rural Development in Western Africa - The Naam Movement and The Six 'S'Document9 pagesTakehiko Uemura, People's Participation Environment-Sustainable Rural Development in Western Africa - The Naam Movement and The Six 'S'intemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- James D. Slack - Limitations in Policy Implementation Research - An Introduction To The SymposiumDocument5 pagesJames D. Slack - Limitations in Policy Implementation Research - An Introduction To The SymposiumintemperantePas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Midnight's Children LPA #5Document6 pagesMidnight's Children LPA #5midnightschildren403Pas encore d'évaluation