Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Chess Strategy in Action

Transféré par

radovanbCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Chess Strategy in Action

Transféré par

radovanbDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

CONTENTS

Contents

Symbols

Dedication

Acknowledgements

6

6

6

Preface

Part 1: Theory and Practice Combine

Introduction and Philosophical Considerations

10

Chapter 1: Broader Issues and Their Evolution

1.1 The Surrender of the Centre

Surrender in the Double e-Pawn Openings

Examples in the Kings Indian Defence

Old and New: Central Capitulation in the French Defence

1.2 Space, Centre, and Exchanging On Principle

Space and Exchanges in the Queens Gambit

Hedgehogs and their Territoriality

The Philosophy of Exchanging in a Broader Context

1.3 The Development of Development

Pleasure before Work!

Revitalizing the Establishment

Development and Pawn-Chains

15

15

25

28

36

36

44

53

56

57

66

71

Chapter 2: Modern Understanding of Pawn Play

Introduction

78

2.1 The Flank Pawns Have Their Say

80

Introduction

General Examples from Practice

Flank Attacks, Space, and Weaknesses

Knights Pawn Advances

Radical Preventative Measures

80

81

86

96

100

2.2 Doubled Pawns in Action

107

The Extension of Doubled Pawn Theory

Doubled Pawns in Pairs

107

109

CHESS STRATEGY IN ACTION

Voluntary Undoubling of the Opponents Pawns

Examples from Modern Play

Doubled f-Pawns

Doubled Pawns on the Rooks File

2.3 The Positional Pawn Sacrifice

Assorted Examples

Kasparovs Pawn Sacrifices

Pawn Sacrifices in Ultra-Solid Openings

2.4 Majorities and Minorities at War

The Effective Minority

Development to the Rescue

111

115

119

127

133

133

139

147

150

151

152

Chapter 3: The Pieces in Action

3.1 An Edgy Day and Sleepless Knight

Eccentric Knights in Double e-Pawn Openings

Knight Decentralization in Contemporary Play

Sleepless Knights

3.2 The Behaviour of Bishops

Bishops Good and Bad

Bishops in Complex Environments

Restless Bishops

3.3 The Minor Pieces Square Off

Bishop and Knight Conflicts

In Praise of the Bishop-Pair

3.4 Her Majesty as a Subject

The Relative Value of the Queen

Early Queen Excursions

156

156

157

163

170

170

181

185

189

189

194

201

201

202

Part 2: Modern Games and Their Interpretation

1:

2:

3:

4:

5:

6:

7:

8:

9:

10:

11:

12:

13:

14:

Topalov-Rozentalis, Batumi Echt 1999

Dautov-Lputian, Istanbul OL 2000

Shirov-Kramnik, Novgorod 1994

Lautier-Shirov, Manila IZ 1990

Beshukov-Volkov, Antalya 2002

Stein-Benko, Stockholm IZ 1962

Gelfand-Bacrot, Cannes 2002

Kasparov-Portisch, Niki 1983

Kveinys-Speelman, Moscow OL 1994

Kasparov-Shirov, Horgen 1994

Serper-Nikolaidis, St Petersburg 1993

Nunn-Nataf, French Cht 1998/9

Voiska-Alexandrova, Warsaw wom Ech 2001

Khouseinov-Magomedov, Dushanbe 1999

210

212

215

216

218

219

221

224

225

227

229

231

234

238

CONTENTS

15:

16:

17:

18:

19:

20:

21:

22:

23:

24:

25:

26:

27:

28:

29:

30:

31:

32:

33:

34:

35:

Kan-Eliskases, Moscow 1936

Leko-Fritz6, Frankfurt rpd 1999

Shmulenson-Sanakoev, corr. 1972-5

Hodgson-Adams, Wijk aan Zee 1993

Shabalov-Karklins, USA 1998

Salinnikov-Miroshnichenko, Ukraine 2000

Kramnik-Leko, Tilburg 1998

Nadanian-Ponomariov, Kiev 1997

Pelletier-Yusupov, Switzerland tt 2002

Nevednichy-M.Grnberg, Romanian Ch (Targoviste) 2001

Van Wely-Piket, Wijk aan Zee 2001

Kasparov-Karpov, Linares 1992

Hbner-Petrosian, Seville Ct (7) 1971

Marciano-C.Bauer, French Ch (Mribel) 1998

J.Shahade-Ehlvest, Philadelphia 1999

Bologan-Svidler, Tomsk 2001

Gulko-Hector, Copenhagen 2000

Petrosian-Korchnoi, Moscow Ct (9) 1971

Shirov-Nisipeanu, Las Vegas FIDE 1999

Timman-Topalov, Moscow OL 1994

Nimzowitsch-Olson, Copenhagen 1924

Bibliography

Index of Players

Index of Openings

5

240

242

243

245

248

249

251

252

254

255

257

258

261

263

266

269

271

274

275

279

281

285

286

288

THE DEVELOPMENT OF DEVELOPMENT

Pleasure before Work!

The majority of master games played today follow standard and at least moderately well analysed openings. But it is instructive (and a lot of

fun!) to look at some of the many experimental

developmental ideas that have been played and

investigated recently. The last 10-15 years have

seen an explosion in the use of exotic irregular

openings, for example. I personally find it a

great delight when I see something new being

played within just the first few moves of the

game. One naturally thinks: how could this not

have occurred to anyone before? Or if the move

occurred once randomly in the past, why didnt

it attract any interest then? Todays players are

inclined to question everything and have few

inhibitions about playing superficially unprincipled moves. This can lead to highly entertaining play, as illustrated by the following game

fragments and the notes within them.

Gabriel Korchnoi

Zurich tt 1999

1 f3 d5 2 c4 d4 3 b4

A fairly normal move, but it introduces a

surprising idea. A related example is Stefan

Bckers 3 c5!? (D), which has a similarly irreverent feel:

rslwkvnt

zpz-zpzp

-+-+-+-+

+-Z-+-+-+-z-+-+

+-+-+N+PZ-ZPZPZ

TNVQML+R

This looks more or less insane, using up a

tempo to expose the c-pawn to attack and give up

control of d5!. But there are some good points as

well; for one thing, White has the concrete idea

of 4 a4+ c6 5 b4!. M.Grnberg-Rahman,

57

Cairo 2000 continued 3...c6 4 a4 (still intending b4-b5, followed by moves such as b2

and a3-c4) 4...d5 5 b4 e5 6 e3 d7 7 b5

d8? (7...xc5 8 a3! b4 9 b2 dxe3 10

fxe3 d6 11 d4 d5 12 c4 e4 13 0-0-0

gave White rapid development in M.GrnbergPopescu, Romanian Cht (Timisu de Sus) 1998)

8 c4 e4 9 c3! f5 (9...dxc3?? 10 xf7+)

10 d5 e6 11 c6 bxc6 12 bxc6 c8 13 0-0

and Blacks position had fallen apart. In my database White has scored 5/6 after 3 c5, with a

performance rating of over 2700!

3...f6 4 e3 e5

So far, Black has played a normal solution to

3 b4, one which has discouraged players on the

white side of this line for years. But now:

5 c5!?

This extravagant move has suddenly received

some serious attention. It seems ridiculous to

use a whole tempo to give up the key d5-square

and expose oneself to a crippling ...a5. On the

positive side, White stops ...c5 at all costs and

temporarily prevents Black from castling after

c4 or b3. At first thought, neither of these

are terribly impressive goals, but there are concrete features as well:

5...d3!?

This intends to cut off Whites f1-bishop and

hamper his development for a long time to come.

However, its awfully ambitious, and Korchnoi

himself (playing Black) was somewhat sceptical

after the game. Quite fascinating play can follow the obvious 5...a5 after 6 b5+! c6 7 c4,

and here Nikolaevsky-Savchenko, Kiev Platonov mem 1995 continued 7...g4! with unclear play. What good did Whites check on

move 6 do him? It turns out that, had Black

played the natural 7...axb4, White could have

played 8 xe5!, intending 8...fxe5? (correct is

8...h6! 9 f3 xc5 10 0-0 with an unclear

game) 9 h5+ d7 10 f5+ c7 11 xe5+

d7 (11...d6 12 cxd6+ b6 13 b2) 12

e6+ e8 13 xc8+, etc. Note that if White

had played 6 c4 instead, then after 6...axb4, 7

xe5?! would be inferior due to 7...fxe5 8

h5+ d7 (9 f5+? c6!). Very devious!

6 b3!?

6 b2 had been played before, so as to meet

6...a5 with 7 a3. The text-move is much more

interesting, allowing the queenside to be shattered for the sake of concrete tactics.

58

CHESS STRATEGY IN ACTION

6...e4 7 d4 a5 8 c3

This game caught the attention of a number

of strong players. Here GM Pelletier gave 8

e6 e7 9 xf8 xf8 10 b5 e6 11 a4 f5

12 a3 c6 with an advantage for Black, although Bcker then suggests 13 g4! to break up

the pawn-chain.

8...f5 (D)

rslwkvnt

+pz-+-zp

-+-+-+-+

z-Z-+p+-Z-Sp+-+

+QSpZ-+P+-Z-ZPZ

T-V-ML+R

Black has now made eight straight pawn

moves! Korchnoi demonstrates that there is

more than one creative player in this game.

9 e6!

This move was condemned at the time on account of the course of the game, but turns out to

be correct.

9...e7?!

None of the annotators liked 9...xe6, but

this is probably best. There could follow 10

xe6+ e7 11 b5 d7 12 c4 c6 13 f3! exf3

14 gxf3 g6 15 f4 with a small edge for White.

10 xf8?

Korchnoi recommended 10 a4+!, which

is very strong. White may not seem to have

gained much after 10...f7 (10...c6? 11 d5;

10...d7? 11 xc7+ d8 12 b5 is winning for

White), but the queen belongs on a4 and the extra tempo makes a huge difference. Korchnoi

gave 11 xf8 xf8 12 a3 f6 13 f3 f7 14

fxe4 fxe4 15 g3 e5 16 b5 e8 17 g2 g8 18

0-0 f5 19 c4+ h8 20 xf5! xf5 21 f1

followed by capturing on e4 with a clear advantage for White.

10...xf8 11 b5?!

Korchnoi considered 11 a4 better despite

the fact that 11...a6! 12 xa5 c6! gives Black

the initiative.

11...e6 12 a4

A vital tempo lost by comparison with the

note to move 10.

12...d7

After this move Black was clearly better and

went on to win. Such a game reminds us that

chess is still wide open to new approaches.

In the following game we see another bizarre-looking idea that is rapidly becoming a

main line:

Zurek Hraek

Czech Cht 2001/2

1 b3 e5 2 b2 c6 3 e3 f6 4 b5

White develops his bishops before his knights,

which tends to be an invitation to oddity. Now

the e5-pawn is threatened.

4...d6!? (D)

Doesnt that block the d-pawn? Theres a

game Suhle-Anderssen, Breslau 1859 with this

move, and then nothing that I can find for almost

120 years! Instead, Black has played 4...d6 here

as a matter of course.

r+lwk+-t

zpzp+pzp

-+nv-s-+

+L+-z-+-+-+-+-+

+P+-Z-+PVPZ-ZPZ

TN+QM-SR

5 a3!?

Knight to the rim! White answers claustrophobia with literal eccentricity, and would obviously like to play c4. Anderssens 1859

opponent played the drab 5 d3. Any such slow

move allows ...0-0, ...e8, ...f8, and ...d5.

In Arencibia-Efimov, Saint Vincent 2001,

White played 5 g4!?, which is quite in the spirit

of things so far! But g5 really isnt much of a

threat, and after 5...0-0 6 c3!? b4 7 g5

xc3! 8 xc3 e4, Black was doing well.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Summary of David Edmonds & John Eidinow's Bobby Fischer Goes to WarD'EverandSummary of David Edmonds & John Eidinow's Bobby Fischer Goes to WarPas encore d'évaluation

- Kramnik, Kasparov and ReshevskyDocument6 pagesKramnik, Kasparov and Reshevskyapi-3738456Pas encore d'évaluation

- Interview With Kasparov About Mikhail TalDocument10 pagesInterview With Kasparov About Mikhail TalEverton AmarillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Winter, Edward - Chess - RecordsDocument13 pagesWinter, Edward - Chess - RecordsValarie WalkerPas encore d'évaluation

- FischerDocument5 pagesFischerSagnik RayPas encore d'évaluation

- Chess Shannon Botvinnik PDFDocument22 pagesChess Shannon Botvinnik PDFBta raltePas encore d'évaluation

- Edward Winter - KoltanowskiDocument3 pagesEdward Winter - KoltanowskiHarcownik RafałPas encore d'évaluation

- Irving ChernevDocument3 pagesIrving ChernevHamidreza Motalebi0% (1)

- Edward Winter - Earliest Occurrences of Chess TermsDocument11 pagesEdward Winter - Earliest Occurrences of Chess TermsHarcownik RafałPas encore d'évaluation

- Edward Winter - Raymond Keene and Eric SchillerDocument7 pagesEdward Winter - Raymond Keene and Eric SchillerHarcownik RafałPas encore d'évaluation

- The Exploits and Triumphs, in Europe, of Paul Morphy, the Chess ChampionD'EverandThe Exploits and Triumphs, in Europe, of Paul Morphy, the Chess ChampionPas encore d'évaluation

- Scholastic Chess Made Easy: A Scholastic Guide for Students, Coaches and ParentsD'EverandScholastic Chess Made Easy: A Scholastic Guide for Students, Coaches and ParentsPas encore d'évaluation

- Fred Reinfeld: TH TH THDocument9 pagesFred Reinfeld: TH TH THKartik ShroffPas encore d'évaluation

- My Chess World Champions - 64ekharDocument86 pagesMy Chess World Champions - 64ekharshekhar100% (1)

- 160 Chess Puzzles in Two Moves, Part 3: Winning Chess ExerciseD'Everand160 Chess Puzzles in Two Moves, Part 3: Winning Chess ExercisePas encore d'évaluation

- Soviet Chess Strategy ExcerptDocument9 pagesSoviet Chess Strategy ExcerptPopescu IonPas encore d'évaluation

- List of Chess BooksDocument51 pagesList of Chess BooksShanePas encore d'évaluation

- José Raúl Capablanca: The Chess Prodigy: The Chess CollectionD'EverandJosé Raúl Capablanca: The Chess Prodigy: The Chess CollectionÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Capablanca PDFDocument11 pagesCapablanca PDFAshutosh papelPas encore d'évaluation

- Alekhine On CarlsbadDocument17 pagesAlekhine On CarlsbadToshiba Satellite100% (1)

- World Chess Championship - WikipediaDocument111 pagesWorld Chess Championship - WikipediaMostafa HashemPas encore d'évaluation

- FIDE Titles PDFDocument7 pagesFIDE Titles PDFT NgPas encore d'évaluation

- 180 Checkmates Chess Puzzles in Two Moves, Part 5: The Right Way to Learn Chess Without Chess TeacherD'Everand180 Checkmates Chess Puzzles in Two Moves, Part 5: The Right Way to Learn Chess Without Chess TeacherPas encore d'évaluation

- Chess Life 1981 - 06Document72 pagesChess Life 1981 - 06Thalison Amaral100% (1)

- Vassily Ivanchuk Best Game - Online ProofDocument927 pagesVassily Ivanchuk Best Game - Online Proofpedjolliny86Pas encore d'évaluation

- 400 Easy Checkmates in One Move for Beginners, Part 6: Chess Puzzles for KidsD'Everand400 Easy Checkmates in One Move for Beginners, Part 6: Chess Puzzles for KidsPas encore d'évaluation

- Advance Chess - Inferential View Analysis of the Double Set Game, (D.2.30) Robotic Intelligence Possibilities: The Double Set Game - Book 2 Vol. 2D'EverandAdvance Chess - Inferential View Analysis of the Double Set Game, (D.2.30) Robotic Intelligence Possibilities: The Double Set Game - Book 2 Vol. 2Pas encore d'évaluation

- Canada'S Chess Magazine For Kids: September 2019 Number 145Document27 pagesCanada'S Chess Magazine For Kids: September 2019 Number 145Bolo BTPas encore d'évaluation

- Edward Winter - Kasparov's 'Child of Change'Document7 pagesEdward Winter - Kasparov's 'Child of Change'Jerry J MonacoPas encore d'évaluation

- Ccafe Spinrad 31 Colonel Moreau 1Document6 pagesCcafe Spinrad 31 Colonel Moreau 1Anonymous oSJiBvxtPas encore d'évaluation

- Helms American Chess Bulletin V 5 1908Document44 pagesHelms American Chess Bulletin V 5 1908don dadaPas encore d'évaluation

- Scholars Mate 120 Dec 2013Document27 pagesScholars Mate 120 Dec 2013plibylPas encore d'évaluation

- Edward Winter - ZugzwangDocument9 pagesEdward Winter - Zugzwanglordraziel1804Pas encore d'évaluation

- 00 FilesDocument23 pages00 FilesJoshua Leiva MuñozPas encore d'évaluation

- 50 Puzzles From The 2013 Cappelle La Grande Chess TournamentDocument19 pages50 Puzzles From The 2013 Cappelle La Grande Chess TournamentBill Harvey100% (1)

- The Exploits and Triumphs, in Europe, of Paul Morphy, the Chess Champion - Including An Historical Account Of Clubs, Biographical Sketches Of Famous Players, And Various Information And Anecdote Relating To The Noble Game Of ChessD'EverandThe Exploits and Triumphs, in Europe, of Paul Morphy, the Chess Champion - Including An Historical Account Of Clubs, Biographical Sketches Of Famous Players, And Various Information And Anecdote Relating To The Noble Game Of ChessPas encore d'évaluation

- Computer Chess PioneersDocument87 pagesComputer Chess PioneersKartik ShroffPas encore d'évaluation

- Edward Winter - Jeremy GaigeDocument5 pagesEdward Winter - Jeremy GaigeHarcownik RafałPas encore d'évaluation

- Alexander Alekhine: Fourth World Chess ChampionD'EverandAlexander Alekhine: Fourth World Chess ChampionÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Chess Opening Tactics - The French - Advance Variation: Opening Tactics, #3D'EverandChess Opening Tactics - The French - Advance Variation: Opening Tactics, #3Pas encore d'évaluation

- Jeremy Silman - The Reassess Your Chess - Workbook 1st Ed 2001Document220 pagesJeremy Silman - The Reassess Your Chess - Workbook 1st Ed 2001Axente AlexandruPas encore d'évaluation

- Stubbs Canadian Chess Problems PDFDocument64 pagesStubbs Canadian Chess Problems PDFbookprospectorPas encore d'évaluation

- The Triumphs of the Chess Champion Paul Morphy: Account of the Great European TourD'EverandThe Triumphs of the Chess Champion Paul Morphy: Account of the Great European TourPas encore d'évaluation

- Bobby Fischer-My 60 GamesDocument15 pagesBobby Fischer-My 60 GamessaeedPas encore d'évaluation

- Advances in Computer Chess: Pergamon Chess SeriesD'EverandAdvances in Computer Chess: Pergamon Chess SeriesM. R. B. ClarkeÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (2)

- The London Chess Club - An Unpublished Manuscript: A Mysterious 18 Century Script Puzzles The Chess WorldDocument64 pagesThe London Chess Club - An Unpublished Manuscript: A Mysterious 18 Century Script Puzzles The Chess WorldJorge Luis Ojeda100% (2)

- The Essential Sosonko: Collected Portraits and Tales of a Bygone Chess EraD'EverandThe Essential Sosonko: Collected Portraits and Tales of a Bygone Chess EraPas encore d'évaluation

- Lessons in Chess Lessons in LifeDocument139 pagesLessons in Chess Lessons in LifeMaria100% (1)

- How To Beat The Open GamesDocument5 pagesHow To Beat The Open Gamesradovanb100% (1)

- Secrets of Chess IntuitionDocument2 pagesSecrets of Chess IntuitionradovanbPas encore d'évaluation

- Lessons in Chess StrategyDocument4 pagesLessons in Chess StrategyradovanbPas encore d'évaluation

- The Mammoth Book of The World's Greatest Chess GamesDocument9 pagesThe Mammoth Book of The World's Greatest Chess GamesradovanbPas encore d'évaluation

- Modern Chess Opening Repertoire For WhiteDocument5 pagesModern Chess Opening Repertoire For WhiteradovanbPas encore d'évaluation

- 101 Attacking Ideas in ChessDocument5 pages101 Attacking Ideas in Chessradovanb0% (1)

- Anti-Sicilians A Guide For BlackDocument3 pagesAnti-Sicilians A Guide For BlackradovanbPas encore d'évaluation

- Fundamental Chess TacticsDocument6 pagesFundamental Chess TacticsradovanbPas encore d'évaluation

- Applying Logic in ChessDocument8 pagesApplying Logic in Chessradovanb33% (3)

- Chess Training For Budding ChampionsDocument4 pagesChess Training For Budding Championsradovanb50% (2)

- Your First Chess Lessons - ExtractDocument6 pagesYour First Chess Lessons - ExtractStans WolePas encore d'évaluation

- How To Beat 1 d4Document4 pagesHow To Beat 1 d4radovanbPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Beat The Open GamesDocument5 pagesHow To Beat The Open Gamesradovanb100% (1)

- Chess For ZebrasDocument6 pagesChess For Zebrasradovanb0% (2)

- Understanding The Leningrad DutchDocument3 pagesUnderstanding The Leningrad Dutchradovanb33% (3)

- The Cambridge SpringsDocument3 pagesThe Cambridge SpringsradovanbPas encore d'évaluation

- Chess Endgame TrainingDocument7 pagesChess Endgame Trainingradovanb0% (1)

- Order FormDocument5 pagesOrder FormradovanbPas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding The ScandinavianDocument6 pagesUnderstanding The ScandinavianradovanbPas encore d'évaluation

- A Simple Chess Opening Repertoire For WhiteDocument7 pagesA Simple Chess Opening Repertoire For Whiteradovanb33% (3)

- Understanding The Marshall AttackDocument6 pagesUnderstanding The Marshall AttackradovanbPas encore d'évaluation

- The Ruy Lopez A Guide For BlackDocument5 pagesThe Ruy Lopez A Guide For BlackNathan Otten50% (2)

- The Seven Deadly Chess SinsDocument4 pagesThe Seven Deadly Chess Sinsradovanb100% (2)

- Beating The Fianchetto DefencesDocument6 pagesBeating The Fianchetto DefencesradovanbPas encore d'évaluation

- The SlavDocument4 pagesThe SlavradovanbPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Play Chess EndgamesDocument9 pagesHow To Play Chess Endgamesradovanb0% (2)

- Play The Open Games As BlackDocument5 pagesPlay The Open Games As BlackradovanbPas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding Pawn Play in ChessDocument4 pagesUnderstanding Pawn Play in ChessradovanbPas encore d'évaluation

- Anti-Sicilians A Guide For BlackDocument3 pagesAnti-Sicilians A Guide For BlackradovanbPas encore d'évaluation

- Time Loop Hunter 0.38.00 - Walktrhough: by KamelkidoDocument101 pagesTime Loop Hunter 0.38.00 - Walktrhough: by KamelkidoFrancois IsabellePas encore d'évaluation

- Gunning - Whats The Point of The Index - or Faking PhotographsDocument12 pagesGunning - Whats The Point of The Index - or Faking Photographsfmonar01Pas encore d'évaluation

- Miso Hungry Japanese RecipesDocument27 pagesMiso Hungry Japanese Recipesgojanmajkovic0% (1)

- Insignia MotherboardDocument3 pagesInsignia MotherboardAlfred BathPas encore d'évaluation

- Bill Starr - (IM) Back To The Rack 1Document6 pagesBill Starr - (IM) Back To The Rack 1TomSusPas encore d'évaluation

- Bet Dwarka TrekkingDocument9 pagesBet Dwarka TrekkingVaibhav BhansariPas encore d'évaluation

- Sweet DreamDocument2 pagesSweet DreamfatihsekerPas encore d'évaluation

- The Man Who Invented Flying SaucersDocument4 pagesThe Man Who Invented Flying SaucersProfessor Solomon100% (1)

- ReadmeDocument5 pagesReadmeparklane79Pas encore d'évaluation

- Cfe e 1631707075 All About Sea Turtles Differentiated Reading Comprehension Ver 2Document17 pagesCfe e 1631707075 All About Sea Turtles Differentiated Reading Comprehension Ver 2hanyPas encore d'évaluation

- Amar STD 4 Project Hemispheres of The EarthDocument17 pagesAmar STD 4 Project Hemispheres of The EarthAliyah AliPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample Lead-Up GameDocument2 pagesSample Lead-Up GameMa. Christina Angenel RamosPas encore d'évaluation

- Chương Trình Tiếng Anh Tăng Cường Khối 3Document12 pagesChương Trình Tiếng Anh Tăng Cường Khối 3nguyenPas encore d'évaluation

- Charles Burney PDFDocument187 pagesCharles Burney PDFConsuelo Prats RedondoPas encore d'évaluation

- Catalog RomFilm2015 Preview 051Document92 pagesCatalog RomFilm2015 Preview 051MairenePas encore d'évaluation

- FIBA Basketball Equipment 2020 - V1Document30 pagesFIBA Basketball Equipment 2020 - V1JilodelPas encore d'évaluation

- CHAIRIL Anwar Is A Legendary Poet Known AsDocument2 pagesCHAIRIL Anwar Is A Legendary Poet Known AsIndah Eka AsrianiPas encore d'évaluation

- Respuestas ActividadesDocument2 pagesRespuestas ActividadesAnonymous MjHq3yp0% (1)

- q2 Music 9 Las Melc 2Document8 pagesq2 Music 9 Las Melc 2aleah katePas encore d'évaluation

- Daily Revenue ReportDocument24 pagesDaily Revenue ReportIzraf AsirafPas encore d'évaluation

- enDocument44 pagesenRegistr Registr90% (10)

- Philippine Airlines Sample TicketDocument1 pagePhilippine Airlines Sample TicketBob ReyraPas encore d'évaluation

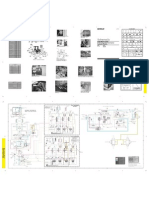

- Hydraulic System Schematic 914-g PDFDocument2 pagesHydraulic System Schematic 914-g PDFpupoz100% (7)

- Pioneer Pdr-w839 ManualDocument52 pagesPioneer Pdr-w839 ManualAndrew LebedevPas encore d'évaluation

- 09 Phak ch7Document42 pages09 Phak ch7Chasel LinPas encore d'évaluation

- Sony Ericsson w995 Troubleshooting ManualDocument125 pagesSony Ericsson w995 Troubleshooting ManualPeter HillPas encore d'évaluation

- Quotes From Football (Soccer) TournamentsDocument23 pagesQuotes From Football (Soccer) TournamentsBrian McDermottPas encore d'évaluation

- ch01 20220628122652Document8 pagesch01 20220628122652Iulia AlexandraPas encore d'évaluation

- How ComeDocument24 pagesHow ComeGreenPas encore d'évaluation

- KING 2011: Parand Software GroupDocument35 pagesKING 2011: Parand Software GroupOmid ZamaniPas encore d'évaluation