Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Why Moocs

Transféré par

Ashokkumar ParmarTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Why Moocs

Transféré par

Ashokkumar ParmarDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

WHY MOOCS FOR THE FUTURE OF INDIAN HIGHER EDUCATION

WHY MOOCS FOR THE FUTURE OF INDIAN HIGHER

EDUCATION

Shri Bhadresh I Patel1, Shri Kiran M. Dave2, Shri Anilkumar A. Mistry3,

Shri

Ashokkumar A. Parmar4

1

Lecturer(SG), Computer Engineering Department, B.&B. Institute of Technology, Vallabh Vidyanagar, Gujarat,

India, Email: bipatel11@gmail.com

2

Lecturer(SG), Computer Engineering Department, B.&B. Institute of Technology, Vallabh Vidyanagar, Gujarat,

India, Email: kiran_1958@yahoo.com

3

Lecturer, Electrical Engineering Department, B.&B. Institute of Technology, Vallabh Vidyanagar, Gujarat, India,

Email: amistry8@gmail.com

41

Lecturer(SG), Electrical Engineering Department, B.&B. Institute of Technology, Vallabh Vidyanagar, Gujarat,

India, Email:parmarashok2002hod@gmail.com

Abstract The status of education has always been the primary factor of a nation that defines its academic

capital, human resource and vision of development. Replacing this education sector with the recent

advancements of technology would be one of the most concrete steps towards national development. In India,

20 million students with 20000 different courses contributed by 200 top universities and also over 5,000 or

more engineering colleges affiliated to different universities, offer conventional and engineering education.

Teachers in colleges do the teaching, but universities rigidly control the program of study, syllabus, and

examinations. The quality of education, is a matter of concern. MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses)

permit learners to access and benefit from the teaching by renowned professors. MOOCs offer an

unprecedented opportunity to revitalize education. These cause complete dis-intermediation of the university

system, making them very affordable; however, they have several shortcomings in their present form.

Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) have evolved as a new paradigm of digitized open education which

could be implemented in a massive domain of India. In a developing country like India where significantly

large number of people live in rural areas and cannot afford quality education, MOOCs can definitely be

considered as game changer. MOOC is a platform where faculties and subject experts from all universities

and organizations across the world, come together to teach you the subject of your choice available in the

MOOC providers list.

Keywords Massive Online Open Courses (MOOCs), Online Education, India, Higher Education (HE)

I.

INTRODUCTION

The 2000s saw changes in online, or e-learning and distance education, with increasing online

presence, open learning opportunities, and the development of MOOCs. The special feature of

any correspondence or distance education until now has only been the transfer of courseware

through online medium. Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) have recently received a

great deal of attention from the media, entrepreneurial vendors, education professionals and

technologically literate sections of the public. The promise of MOOCs is that they will

provide free to access, cutting edge courses that could drive down the cost of university-level

education and potentially disrupt the existing models of higher education (HE).[4]

Massive Open Online Courses (commonly MOOCs) has emerged as a recent path-breaking

educational paradigm promoting openness in education to the all higher education institutes

MOOCs are also intending the business attentions since the extensive market in education is

International Journal of Engineering Research and Advanced Development (ISSN

2395-5163) | 7

WHY MOOCS FOR THE FUTURE OF INDIAN HIGHER EDUCATION

unleashing potential. MOOCs scenario of the world, the prime hubs for conducting MOOCs

lie concentrated within the developed countries of the first world, especially UK, US and

Australia. But China, India etc. like developing countries contribute the majority of students

going abroad for higher education in these developed countries. Even the students from the

developing countries accessing MOOCs count to a significant number in terms of the total

student community accessing MOOCs. In India education sector also contribute economy and

significant development. Youths constitute about majority of the national population which

signify a huge potential area for higher education, India would obviously become a gamechanging superpower in terms of MOOCs in Asia. [6]

II. HIGHER EDUCATION IN INDIA [8]

The modern university in India is a Western import. It goes back to the establishment of three

universities in Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras in 1857, as the colonial government looked to

educate a class of Indians to staff the growing bureaucracy. By the turn of the century, India had

five universities and 145 colleges, with 18,000 students (almost all male).

In 1947, when India became independent, 21 universities and 496 colleges were in operation. The

gross enrollment ratio (GER) was less than 1 percent, and female students were barely a tenth of

the total. But over the past quarter century, there has been an explosive expansion in Indian higher

education (Table 1).[8]

Table 1, Data for 199091 is from Ministry of Human Resource Development, Statistics of

Higher and Technical Education, 200809; data for 201212 is from the All-Indian Survey

on Higher Education, 201213.

199091

201213

184

184

Universities

Colleges

5748

5748

Students (millions)

4.9

4.9

GER (%)

4.3

4.3

Source: Data from Ministry of Human Resource Development

Four principal factors have driven this rapid growth. The first is simply demographic. With more

than 30 percent of the population below the age of 15 and more than five million people entering

the 1524 age group annually, the demographic momentum in the country is huge. Between

19912010, the population increase in the 1564 age group was 249 million; between 20102030,

it will increase by an additional 230 million.

Second, the college-age population is more prepared for higher education than its predecessors.

Near universal primary enrollment, resulting from a combination of public funding and private

efforts, has led to substantially higher secondary school enrollments and has been further boosted

by a national secondary school program launched in 2009.

Third, rapid economic growth as well as greater integration into the global economy has increased

the demand for people with advanced knowledge and skills. Finally, demand for higher education

is being driven by major changes in the aspirations of the population, as well as state policy that

aims to increase the gross enrollment ratio to 30 percent by 2020. Already, India has the second

highest number of students (after China) enrolled in institutions of higher education in the world.

International Journal of Engineering Research and Advanced Development (ISSN

2395-5163) | 8

WHY MOOCS FOR THE FUTURE OF INDIAN HIGHER EDUCATION

It should, however, be emphasized that quantity is not quality. The vast majority of the students

are very poorly trained.

The supply response has been taking place at several levels. The firstand the most important in

quantitative termsis the rapid expansion of private colleges (and increasingly, private

universities), largely affiliated with state-level universities, especially in professional education.

By 2013, nearly three fourths of all colleges in India were privately managed.

The second has been the effort of the federal government to expand the supply of national higher

education institutions. While these are regarded among the best in the country, they enroll only a

tiny fraction of all postsecondary students.

Third, a new emphasis on skilling came with the 2008 creation of the National Skill

Development Corporation (NSDC), which is charged with providing skills to 500 million people

by 2022, much of it by private vocational training providers (VTPs) and assessing bodies. The

central government is providing funds to state governments for the reimbursement of training

and assessment costs. Finally, distance education constitutes 11.9 percent of the total enrollment

in higher education. With all this activity, Indian higher education faces multiple challenges. The

governance of higher education is weak, both at the regulatory level and within institutions of

higher education. The quality of education for the vast majority of institutions and students is

dismal. Surveys suggest that barely a quarter to a third of graduates are employable, lacking both

domain knowledge and soft skills. With millions of young Indians entering labor markets with

aspirations and formal credentials but few skills, the economic, social, and political

consequences of this mismatch do not augur well. At the heart of this challenge is a massive lack

of qualified personnelironically the very purpose of higher educationto administer, teach, or

conduct research. As of July 2014, the faculty vacancy rate in the Indian Institutes of Technology

and the 39 central universities was 40 percent (Rukmini, 2014).Fragmentation increases the

challenge. The average size of a higher education institution in India is about 700 students, less

than half of that in China.

III. TRENDS OF EXPANSION OF HIGHER EDUCATION IN INDIA A VISION OF

OPEN LEARNING AND MOOCS [6], [8]

According to Martin Trows classification of stages of Development of higher education (Trow,

2006), a country is at an elite stage of higher education when the gross enrolment ratio (GER) is

less than 15 per cent; at a stage of massification when the GER is between 15 and 50 per cent

and at a stage of universalization when the GER reaches 50 per cent mark. As per this definition,

the higher education sector in India with a GER of 21.1 per cent in 2012-13 is in its initial stages

of massification.

Although the system remains at the lower end of the massification, India enrolls a larger number

of students than the largest country (such as USA) which has universalized higher education.

With around 28.5 million students, 0.70 teachers and 35 thousand institution in 2011-12 (MHRD,

2012a), the higher education sector in India is not only large but also the second largest in the

world after China. Higher Education is a diversified sector and huge domain in India. Indias

higher education system ranks third largest in the world after China and the United States. The

expansion of the higher education sector in India, especially in the recent past, is very impressive.

Between 1951 and 2012 the number of universities and institutions of national importance increased

from 27 to 621; colleges from 578 to 34.9 thousand and students from around 200 thousand to 28.5

million. However, the expansion was the fastest in the decade of 2000s. The enrolment increased from

8.8 million in 2001-02 to 28.5 million in 2011-12. This implied an addition of around 2 million students

annually to the sector making it the highest expansion for any decade (1).

International Journal of Engineering Research and Advanced Development (ISSN

2395-5163) | 9

WHY MOOCS FOR THE FUTURE OF INDIAN HIGHER EDUCATION

The growth and expansion of higher education in India during the post-independence period can broadly

be categorized into three stages: i) a stage of high growth and limited access (1950-70); ii) a stage of

declining growth in enrolment (1970-1990); and iii) a stage of revival and massive expansion of

enrolment in higher education 1990 and after (Varghese, 2014). Let us discuss the characteristics of each

of these stages.

Open and distance learning in India is the largest of its kind in the world. India boasts of having

Indira Gandhi Open University, the largest university in the world, In due course, more open

universities (including 12 state open universities and 119 institutions of correspondence courses

in conventional universities) were introduced under the headship of Distance Education Council

(DEC) to cater wide and open education throughout [4]. However, with the ensuing digital era,

different courses in these open universities have been supported with digital study materials.

Some of these are also available online. However, the number of online courses is scarce

compared to the whole course domain. Hence MOOCs, India has no concrete Government setup

running to provide such courses. However different private operated MOOCs providers of Indian

origin provide such courses to the learners. Discussing over a world scenario, Indian students lag

in MOOCs enrolment compared to the developing nations. But when compared within the

developing nations India holds the highest number of students for MOOCs enrolment. Also it

leads the BRICS nations in this respect. But analyzing the status in a deeper view, reports

showcase that most of these MOOCs enrollees from India have enrolled for the MOOCs

providers having foreign origin. This interprets the poor scenario of India-based MOOCs in spite

of having a huge prospective market.

IV. A NEW MODEL FOR HIGHER EDUCATION [7], [2]

While India's sheer size may make its higher education challenges more immense, the underlying

issues are common across most low and middle-income countries. Traditional brick-and-mortar

higher education institutions are failing to meet the educational needs of growing populations in

India and elsewhere in the Global South.

Developing academic programs, building reputations, attracting students, recruiting faculty, and

creating appropriate governance structures require large resources of time, talent, and treasury, as

well as coordinated private-public partnerships to achieve national scale. While countries in the

Global South, India included, are embarking on that path, it is not a realistic way to meet

educational demand, particularly in the near term.

In their paper focusing on the effect MOOCs may have on business education, Ulrich and

Terwiesch (2014) illuminate the very high cost of providing traditional university education. The

researchers focus on business education, but they believe (and we agree) that the implications of

their findings extend beyond business school to higher education in general. They find that by

taking advantage of online education that uses chunked asynchronous video paired with adaptive

testing, as MOOCs generally do, business schools can save sizeable sums of money while still

delivering a quality product.

In one example, an online executive education program with a tenure-track faculty and $4,000 fee

generates $1,000,000 in surplus for the business school over the 10-year life of a course, while a

comparable MOOC-style course with a price point of $400 would generate $3,680,000 in surplus

over the same period. The difference comes from cost savings during each subsequent course

offering after the course module has been developed, as well as from the significantly expanded

enrollment opportunities of the MOOC-style course.

International Journal of Engineering Research and Advanced Development (ISSN

2395-5163) | 10

WHY MOOCS FOR THE FUTURE OF INDIAN HIGHER EDUCATION

In places where well-functioning higher education systems already exist, it is hard to imagine a

sea-change in the way education is delivered along the lines of what Ulrich and Terwiesch outline.

A powerful combination of student, faculty, and administration interests are likely to maintain the

residential university experience, along with the many tacit benefits that come along with it.

However, in India and much of the Global South, where states and universities are struggling to

meet demand for higher education, a new educational model that offers high-quality courses at a

low price to a much larger number of students is exactly what is needed.

Another area of cost saving not touched on by Ulrich and Terwiesch is the ability to take

advantage of the course-development work that leading universities around the world are already

involved in. Coursera, edX, the Open Learning Initiative, and other online course providers have

already developed hundreds of free courses. Some organizationssuch as Kepler, based in

Kigali, Rwandaare already taking advantage of these courses to educate college-age Rwandans.

We believe that traditional university coursessupplemented by high-quality online courses

offered by leading universities and third-party organizations that repurpose freely available

content from universities around the worldcan comprise a new higher education ecosystem in

the Global South. This would not only provide higher education access to a far greater number of

students but also improve quality both directly and by example, as well as increase the variety of

and flexibility of higher education programs to better suit the diverse needs of students.

In order for this new model to succeed, the credentialing challenge must be met. If local

universities are offering their own content online for credit, the question of credentialing or

obtaining a degree will be handled by that university. However, for third-party organizations that

assemble a curriculum of free courses from a group of universities and facilitate student

completion of those courses, the question of who, if anyone, certifies that these students have

learned the course material remains open.

Without trusted credentialing that can signal to an employer that a student has mastered the course

content, the supply-chain from education to employment will break down and many students'

primary motivation for enrollment will disappear. In a later section of this paper we look more

closely at this issue

V. THE FIRST WAVE OF INDIAN MOOCs STUDENTS [7],[9]

A new education landscape that combines online learning environments with brick-and-mortar

classrooms may be able to deliver high-quality education at an affordable cost to a large number

of students, but it will need to attract students. Findings from data and surveys of the first 1.7

million participants in Penn's Coursera courses suggest that this will not be a problem. Indeed,

students around the world are clamoring for new educational opportunities.

Two thirds of the 1.7 million students who have enrolled in a Penn Coursera course have come

from outside the United States. Half of those non-US students, over 500,000 enrollees, have been

from non-OECD countriesdespite the fact that the largest MOOC providers, including

Coursera, are based in the United States; more than half of Coursera's institutional partners are US

universities; and MOOCs are taught almost exclusively in English.

Furthermore, access to MOOCs requires adequate technology and a high-speed internet

connection in order to stream or download video content, complete quizzes, and participate in the

student forums. Despite these barriers, international participants demonstrate enormous interest in

MOOC options.

Students from India in particular are signing up for MOOCs in large numbers. In virtually every

study, Indians comprise the second largest national group enrolling in these courses (after

participants from the United States), ranging as high as 13.2 percent in an analysis of the first year

International Journal of Engineering Research and Advanced Development (ISSN

2395-5163) | 11

WHY MOOCS FOR THE FUTURE OF INDIAN HIGHER EDUCATION

of edX MOOCs at Harvard and MIT (Ho et al., 2014). Indians make up 6.9 percent of the first 1.7

million students to take a MOOC offered by Penn. They significantly outpace the next largest

groups: Brazilians (4.0 percent), Russians (3.3 percent), Canadians (3.3 percent), and Chinese (1.9

percent). An additional 2.5 percent of MOOC students are Indians living abroad.

This population of Indian students is an interesting case study of the role that open online

education could play in higher education in the developing world, what types of students are

likely to take advantage of new online education models, and what stumbling blocks exist on the

road to wider MOOC adoption.

First, MOOCs are supplementing rather than substituting for traditional higher education for

many students in India. MOOC students are on average very highly educated (or rather,

credentialed), and Indian MOOC students are more educated than their non-Indian peers. Most

(84.3 percent) of Indian MOOC students have postsecondary degrees; nearly 40 percent have

graduate degrees (Table 2).

But nearly 40 percent of Indian MOOC students are also currently enrolled in a traditional

undergraduate or graduate education settinga larger number than among the non-Indian MOOC

student population (Table 2). Of these students, approximately half are currently enrolled in an

undergraduate program, and half are enrolled in a graduate program. Indian MOOC students, with

a median age of 26, are also significantly younger than other MOOC participants.

So while the majority of Indian MOOC enrollees are already in the workforce, a sizeable and

larger-than-average number of young Indians are combining traditional learning with MOOC

learning. These students may be supplementing poor-quality traditional educational options,

enrolling online in courses that are not being offered by their brick-and-mortar institutions, or

even preparing themselves for entrance exams into the most competitive traditional institutions.

The picture that seems to be emerging in India is one in which MOOCs are able to fill in some of

the gaps of an underperforming higher education system and provide opportunities that students

are eager to avail themselves of.

However, the fact that so many of the Indian MOOC students have already passed through the

Indian higher education system suggests that MOOCs are not primarily a higher education tool

rather, they mostly serve professional-training needs. The majority of Indian MOOC students are

employed full-time and using the courses to develop skills that help them at their current job or

will help them find a new one (Christensen et al., 2013). Employed Indian MOOC students and

those currently looking for work are predominantly drawn from industries with relatively welldefined skill sets and promising job prospects. Specifically, 70 percent of employed Indian

MOOC students work in STEM fields (engineering, computers or mathematics) or business.

VI. BARRIERS TO ACCESS [4], [7]

While there is much to be optimistic about in terms of the potential for MOOCs to augment

higher education in the developing world, it is important to consider the barriers to access and the

populations that have been largely excluded from the first wave of MOOCs.

There are at least four major barriers that students need to overcome in order to enroll in and

engage with a MOOC in a technical field: 1) reliable access to broadband internet and a computer,

tablet, or mobile phone to retrieve course content, 2) adequate primary and secondary education

that has prepared the student to understand university-level academic content, 3) strong English

language skills, and 4) free time to devote to watching lectures, completing readings, and

submitting assignments. Courses in the humanities and the social sciences have the additional

challenge of contextually grounded content and its appropriateness in different cultural settings.

International Journal of Engineering Research and Advanced Development (ISSN

2395-5163) | 12

WHY MOOCS FOR THE FUTURE OF INDIAN HIGHER EDUCATION

In the developing world in general, and in India specifically, these barriers are undoubtedly

restricting access to MOOCs to the small subset of the population that is middle and upper

income. Moreover, two major groups are conspicuously underrepresented among Indian MOOC

students, even if they pass the income test.

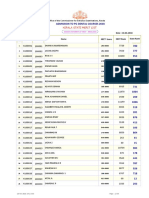

Table 2, POPULATION AND MOOC PARTICIPATION IN INDIA'S 10 LARGEST CITIES

City Name

Mumbai

Delhi

Chennai

Bangalore

Hyderabad

Ahmedabad

Pune

Kolkata

Jaipur

Total

Population (2011)

12,478,447

11,007,835

8,696,010

8,425,970

6,809,970

6,352,254

5,049,968

4,486,679

3,073,350

66,380,483

Percent of Total

Population (2011)

1.0%

0.9%

0.7%

0.7%

0.6%

0.5%

0.4%

0.4%

0.3%

5.5%

Percent of Indian

MOOC Students

17.3%

16.9%

7.8%

19.3%

6.2%

0.9%

2.7%

3.5%

0.5%

75.1%

First, Indian women make up just 20 percent of Indian MOOC students. This female enrollment

rate is less than half that of non-Indian MOOC participants. It also stands in stark contrast to the

gender breakdown at traditional Indian universities, where the Gender Parity Index (GPI) has

climbed to 0.86, indicating less unequal participation among men and women in traditional higher

education in India.

There are a number of factors that are likely contributing to this gender disparity in MOOCs,

including unequal access to technology, lower rates of female participation in STEM fields, and

limited job prospects for females. Whatever the causes, the gender disparity is a major obstacle to

overcome if MOOCs are to be used as a tool to meaningfully and equitably expand educational

opportunities in the developing world.

Second, few rural residents of India are enrolling in MOOCs. According to a geo location of IP

addresses, three quarters of all Indian MOOC students reside in one of India's ten largest cities,

despite the fact that those cities only account for approximately 6 percent of the Indian population

(Table 2). Not only that, but over half of Indian MOOC students come from Mumbai, Delhi, or

Bangalore, which suggests that enrollment in MOOCs is an urban phenomenon that is very highly

concentrated in the most populous, developed, and prosperous Indian cities.

Access to internet and computing technology is an obvious hurdle for MOOC access in rural

India, along with significantly weaker English language skills that would make it impossible to

understand most MOOC courses. However, with two thirds of India's population still residing in

rural areas, any conversation about how MOOCs can help meet educational demand that the

traditional higher education system cannot needs to consider how to do so in rural as well as urban

areas.

International Journal of Engineering Research and Advanced Development (ISSN

2395-5163) | 13

WHY MOOCS FOR THE FUTURE OF INDIAN HIGHER EDUCATION

In mid-2014, according to data released by the Telcom Regulatory Authority of India (2014), the

total number of internet subscribers was 260 million. Of these, wired internet subscribers were 19

million and wireless subscribers 241 million. Broadband subscribers were 68 million (or around a

quarter of all households). This suggests that to increase access, it will be necessary to deliver

content to mobile devices, customize content for local realities (including language), and build

communities of practice that can leverage peer-to-peer learning.

VII. CONCLUSION

India is the second biggest market for MOOCs (massive open online courses) in the world,

following the US. In time, however, India may surpass the US. After all, India's population is

second to China's and India is third in terms of university enrollment worldwide; respectively the

US and China are first and second for university enrollment at the moment but this may soon

change. [7]

MOOCs represent a huge opportunity for Indians in terms of an open education revolution. It

could potentially give millions access and availability to high quality learning if they have

Internet connectivity. First, there are more applicants than slots at top Indian universities. Second,

millions of Indians live in poverty and are unable to afford or gain access to a higher education.

Dr. Sugata Mitra, however, has shown than even in the slums of India, young Indian children

often have tremendous potential for learning with digital technology. He has shown that kids from

the slums are often more capable of learning at high levels with digital technology than previously

thought or assumed and are essentially diamonds in the rough of an educational forest, so to

speak. Third, Internet connectivity is not always available throughout India, which is often a

barrier for open education and MOOCs. Even when Internet connectivity is available, bandwidth

might be too low or slow for videos to stream. [7]

Fig.1 Top 3 of 98 countries MOOCS University Request [5]

For these reasons and many others, US-based MOOC providers are entering partnerships with

Indian colleges or universities or making alternative arrangements to make MOOCs more

accessible and available in India. The Indian Institute of Technology Bombay (IIT Bombay), for

example, is the first college in India to join not-for-profit edX and to offer MOOCs. The

partnership was created to fill a specific need in India: training engineering teachers. The

partnership will extend an open engineering education to a global audience, though the US and

International Journal of Engineering Research and Advanced Development (ISSN

2395-5163) | 14

WHY MOOCS FOR THE FUTURE OF INDIAN HIGHER EDUCATION

India are the largest populations of edX learners worldwide and will be the primary recipients of

the partnership of an open engineering education.

Coursera and Udacity (both for-profit ventures) have also been making arrangements to make

MOOCs more accessible and available in India. Coursera is working on a mobile application so

students from poorer backgrounds can access MOOCs on Akash tablets. It is also offering a

course on web intelligence and big data with the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi (IIT Delhi).

Perhaps not surprisingly, since Coursera currently produces the largest number of MOOCs

worldwide, they have seen a huge increase in Indian student enrollment as well.

Udacity, too, has seen Indian enrollment increase over the past year. In May, Udacity teamed with

Georgia Tech and AT&T to offer the first online massive open online master's degree program in

computer science for less than $7000 in tuition. The program is specifically targeted to India and

the Middle East. The deal is seen as revolutionary within higher education circles and many

administrators are eagerly awaiting the results.

REFERENCES

[1] Available on: www.it.iitb.ac.in/nmeict/pdfs/MOOCs.pdf retrieved on 11/03/2016

[2] Available on: https://indiamoocs.wordpress.com/ retrieved on 11/03/2016

[3] Available on:

https://indiamoocs.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/ficci_visionpaper_mooche_v0-8.pdf retrieved on 21/03/2016

[4] Available on: http://www.slideshare.net/GO-GN/moocs-for-development-a-study-of-indianlearner-experiences-in-massive-open-online-courses retrieved on 21/03/2016 [5] Available

on: http://www.moocs.co/Higher_Education_MOOCs.html retrieved on 21/03/2016

[6] Available on:

www.researchgate.net/publication/268207412_Massive_Open_Online_Courses_MOOCs_in

_Higher_Education_-_Unleashing_the_Potential_in_India retrieved on 21/03/2016

[7] Available on: https://opensource.com/education/13/8/higher-education-india-moocs retrieved

on 21/03/2016

[8] Available on: http://britishcouncil.in/sites/default/files/indian_higher_education_system.pdf

retrieved on 22/03/2016

[9] Available on: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Wty5brODPU retrieved on 16/03/2016

International Journal of Engineering Research and Advanced Development (ISSN

2395-5163) | 15

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- đề GK 2-1Document6 pagesđề GK 2-1VO THUY SONPas encore d'évaluation

- Quality Assurance in Higher Education The PhilippiDocument8 pagesQuality Assurance in Higher Education The PhilippiRoseann Hidalgo ZimaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Educational & Human Resource Strategic Plan 2008-2020Document164 pagesEducational & Human Resource Strategic Plan 2008-2020Yugesh D PANDAYPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippines: The Role of Language and Education in Globalization Consuelo Quijano University of San Francisco December 15, 2012Document17 pagesPhilippines: The Role of Language and Education in Globalization Consuelo Quijano University of San Francisco December 15, 2012rdusfsdyifuyuPas encore d'évaluation

- Medical Mentor BookletDocument76 pagesMedical Mentor BookletDhananjay Kulkarni100% (1)

- Alam Et Al.Document9 pagesAlam Et Al.cutekPas encore d'évaluation

- Tangazo La Usaili Wa InternshipDocument11 pagesTangazo La Usaili Wa InternshipWahanza RamadhanPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Bharat Garva Club 52 TrackerDocument1 page5 Bharat Garva Club 52 TrackerPANKAJ KUMAR GIRIPas encore d'évaluation

- UCT Postgraduate-Studies BrochureDocument27 pagesUCT Postgraduate-Studies BrochureUsman AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Modern Physics - JEE Main 2023 April - Eduniti - 23320400 - 2023 - 12 - 16 - 19 - 17Document6 pagesModern Physics - JEE Main 2023 April - Eduniti - 23320400 - 2023 - 12 - 16 - 19 - 17atharvjat743Pas encore d'évaluation

- Studentonlineservices Degreeevaluation20172Document2 pagesStudentonlineservices Degreeevaluation20172baluchiifPas encore d'évaluation

- CHAPTER 3 (Teaching Profession)Document72 pagesCHAPTER 3 (Teaching Profession)Lycea Valdez80% (5)

- "MBA" Redirects Here. For Other Uses, SeeDocument4 pages"MBA" Redirects Here. For Other Uses, SeeTanmoy MitraPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 - Proposed Draft MBBS and BDS (Admission House Job and Internship) Regulation 2018 PDFDocument20 pages1 - Proposed Draft MBBS and BDS (Admission House Job and Internship) Regulation 2018 PDFRameesa AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Integrating Special and General Education in Fairfax County Public SchoolsDocument2 pagesIntegrating Special and General Education in Fairfax County Public SchoolsRoosevelt Campus NetworkPas encore d'évaluation

- Bangladesh Education Structure PDFDocument37 pagesBangladesh Education Structure PDFAshraf AtiquePas encore d'évaluation

- Punjab Counselling 2022Document62 pagesPunjab Counselling 2022PrincessPas encore d'évaluation

- Highly Educated Woman in IndonesiaDocument6 pagesHighly Educated Woman in IndonesianisrinayumnakPas encore d'évaluation

- Ph.D. English Literature (5)Document10 pagesPh.D. English Literature (5)Anupriya PalniPas encore d'évaluation

- PTE Academic Recognized Institutions 28th Jan 2022Document62 pagesPTE Academic Recognized Institutions 28th Jan 2022abubakrahmed083Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Strategy - For - Adult - Education PDFDocument64 pagesA Strategy - For - Adult - Education PDFMichelle WilcoxPas encore d'évaluation

- PTPW StatusDocument16 pagesPTPW StatusMeetPas encore d'évaluation

- AICTE announces GPAT 2018 Merit ListDocument400 pagesAICTE announces GPAT 2018 Merit ListKala Suvarna100% (3)

- Setara Tier 5 - 5 March 2017Document12 pagesSetara Tier 5 - 5 March 2017Times MediaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ranklist RevDocument46 pagesRanklist RevMirosh MalapatPas encore d'évaluation

- Jönköping International Business School - Studies - Jönköping UniversityDocument1 pageJönköping International Business School - Studies - Jönköping UniversityElissa TanPas encore d'évaluation

- Course-Transfer MonashDocument3 pagesCourse-Transfer MonashCheeZhen KongPas encore d'évaluation

- Seats Available For M.Sc. Through IIT JAM at NITsDocument12 pagesSeats Available For M.Sc. Through IIT JAM at NITsjolly shringiPas encore d'évaluation