Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Roman Calendar (Wikipedia)

Transféré par

ThriwCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Roman Calendar (Wikipedia)

Transféré par

ThriwDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Roman calendar - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

13/07/2016 11:17

Roman calendar

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Roman calendar changed its form several

times between the founding of Rome and the fall of

the Roman Empire. The common calendar widely

used today is known as the Gregorian calendar and

is a refinement of the Julian calendar where the

average length of the year has been adjusted from

365.25 days to 365.2425 days (a 0.002% change).

From at least the period of Augustus on, calendars

were often inscribed in stone and displayed

publicly. Such calendars are called fasti.

Contents

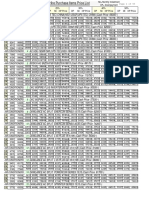

Drawing of the fragmentary Fasti Antiates Maiores (ca.

60 BC), a Roman calendar from before the Julian reform,

with the seventh and eighth months still named Quintilis

("QVI") and Sextilis ("SEX"), and the intercalary month

("INTER") in the far righthand column (see enlarged)

1 History

1.1 Calendar of Romulus

1.2 Calendar of Numa

1.3 Reforms of Gnaeus Flavius

1.4 The Julian calendar

2 Intercalation

3 Months

4 Nundinal cycle

5 Character of the day

6 Years

7 Extant fasti

8 Converting pre-Julian dates

9 See also

10 Notes

11 References

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_calendar

Page 1 sur 12

Roman calendar - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

13/07/2016 11:17

12 Further reading

13 External links

History

The original Roman calendar is believed to have been a lunar

calendar, which may have been based on one of the Greek lunar

calendars.[1] As the time between new moons averages 29.5 days its

months were constructed to be either hollow (29 days) or full (30

days).

Calendar of Romulus

Roman writers attributed the original Roman calendar to Romulus,

the mythical founder of Rome, though there is no other evidence for

the existence of such a calendar and Romulus was often cited as the

The Fasti Praenestini.

founder of practices whose origins were unknown to later Romans.

According to these writers, Romulus' calendar had ten months with

the spring equinox in the first month (likely based on the names of the last months of the year):

Calendar of Romulus

Martius (31 days)

Aprilis (30 days)

Maius (31 days)

Iunius (30 days)

Quintilis[2] (31 days)

Sextilis (30 days)

September (30 days)

October (31 days)

November (30 days)

December (30 days)

The regular calendar year thus consisted of 304 days, with the winter days after the end of December and

before the beginning of the following March not being assigned to any month.[3][4]

The origins of the names are also not entirely clear or agreed upon by modern scholars. Some ancient

explanations are: Martius in honour of Mars, the god of war; Aprilis from aperi, to open: Earth opens to

receive seed; Maius from Maia, goddess of growth (maior, elder); Iunius from iunior (younger). The

remaining six months were named with respect to their position on the calendar: the numbers five to ten in

Latin being quinque, sex, septem, octo, novem and decem, the months were named Quintilis, Sextilis,

September, October, November, and December.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_calendar

Page 2 sur 12

Roman calendar - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

13/07/2016 11:17

Calendar of Numa

Further reforms were attributed, again without firm evidence, to Numa Pompilius, the second of the seven

traditional kings of Rome. The Romans considered even numbers to be unlucky, so Numa took one day from

each of the six months with 30 days, reducing the number of days in the 10 previously defined months by a

total of six days.[5] There were 51 previously unallocated winter days, to which were added the six days

from the reductions in the days in the months, making a total of 57 days. These he made into two months,

January and February, which he prefixed to the previous 10 months. January was given 29 days, while

February had the unlucky number of 28 days, suitable for the month of purification (Februa, the Roman

festival of purification). This made a regular year (of 12 lunar months) 355 days long in place of the

previous 304 days of the Romulus calendar. Of the 11 months with an odd number of days, four had 31 days

each and seven had 29 days each:

Calendar of Numa

Civil calendar

Religious calendar

According to

According to Ovid[7]

Macrobius[3] (modern order due to According to Fowler[8]

and Plutarch[6] Decemviri, 450 BC)

Ianuarius (29)

Ianuarius

Martius

Februarius (28) Martius

Aprilis

Martius (31)

Aprilis

Maius

Aprilis (29)

Maius

Iunius

Maius (31)

Iunius

Quintilis

Iunius (29)

Quintilis

Sextilis

Quintilis (31)

Sextilis

September

Sextilis (29)

September

October

September (29) October

November

October (31)

December

November

November (29) December

Ianuarius

December (29) Februarius

Februarius

Reforms of Gnaeus Flavius

In 304 BC Gnaeus Flavius, a pontifical secretary, introduced a series of reforms. It is generally believed that

he initiated the custom of publishing the calendar in advance of the month, depriving the pontiffs of some of

their power, but allowing for a more consistent calendar for official business.[9]

The Julian calendar

Julius Caesar, as Pontifex Maximus, reformed the calendar in 46 BC. The new calendar became known as

the Julian calendar. Quintilis was renamed Iulius (July) in honour of Julius Caesar in 44 BC by Mark

Antony. A further change was made during the reign of his successor Augustus, when, apparently following

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_calendar

Page 3 sur 12

Roman calendar - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

13/07/2016 11:17

the Senate, the plebiscite Lex Pacuvia de mense augusto renamed Sextilis Augustus (August) in 8 BC.[10][11]

Some documents state that the date of the change of the name started between 26 and 23 BC but the date of

the Lex Pacuvia is certain.

Intercalation

The regular calendar had only 355 days, which meant that it would quickly be unsynchronized with the solar

year, causing, for example, agricultural festivals to occur out of season. The Roman solution to this problem

was to periodically lengthen the calendar by adding extra days to February. February consisted of two parts,

each with an odd number of days. The first part ended with the Terminalia on the 23rd, which was

considered the end of the religious year, and the five remaining days formed the second part. To keep the

calendar year roughly aligned with the solar year, a leap month, called the Mensis Intercalaris ("intercalary

month"), was added from time to time between these two parts of February. The second part of February was

incorporated in the intercalary month as its last five days, with no change either in their dates or the festivals

observed on them. This follows naturally from the fact that the days after the Ides of February (in an

ordinary year) or the Ides of Intercalaris (in an intercalary year) both counted down to the Kalends of March.

The nones and ides of Intercalaris occupied the normal positions of the 5th and 13th of the month.

The third-century writer Censorinus says:

When it was thought necessary to add (every two years) an intercalary month of 22 or 23 days,

so that the civil year should correspond to the natural (solar) year, this intercalation was in

preference made in February, between Terminalia [23rd] and Regifugium [24th].[12]

The fifth-century writer Macrobius says that the Romans intercalated 22 and 23 days in alternate years

(Saturnalia, 1.13.12), the intercalation was placed after 23 February and the remaining five days of February

followed (Saturnalia, 1.13.15). To avoid the nones falling on a nundine, where necessary an intercalary day

was inserted "in the middle of the Terminalia, where they placed the intercalary month". (Saturnalia,

1.13.16, 1.13.19).[13]

This is historically correct. In 167 BC Intercalaris began on the day after 23 February [14] and in 170 BC it

began on the second day after 23 February.[15] Varro, writing in the first century BC, says "the twelfth month

was February, and when intercalations take place the five last days of this month are removed."[16] Since all

the days after the Ides of Intercalaris were counted down to the beginning of March Intercalaris had either 27

days (making 377 for the year) or 28 (making 378 for the year).

There is another theory which says that in intercalary years February had 23 or 24 days and Intercalaris had

27. No date is offered for the Regifugium in 378 - day years.[17]

The Pontifex Maximus determined when an intercalary month was to be inserted. On average, this happened

in alternate years. The system of aligning the year through intercalary months broke down at least twice: the

first time was during and after the Second Punic War. It led to the reform of the Lex Acilia in 191 BC, the

details of which are unclear, but it appears to have successfully regulated intercalation for over a century.

The second breakdown was in the middle of the first century BC and may have been related to the

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_calendar

Page 4 sur 12

Roman calendar - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

13/07/2016 11:17

increasingly chaotic and adversarial nature of Roman politics at the time. The position of Pontifex Maximus

was not a full-time job; it was held by a member of the Roman elite, who would almost invariably be

involved in the machinations of Roman politics. Because the term of office of elected Roman magistrates

was defined in terms of a Roman calendar year, a Pontifex Maximus would have reason to lengthen a year in

which he or his allies were in power, or shorten a year in which his political opponents held office. For

example, Julius Caesar made the year of his third consulship in 46 BC 445 days long.

Months

In the earliest times, the three reference dates were probably declared publicly, when appropriate lunar

conditions were observed. After the reforms of Numa, they occurred on fixed days.

Kalendae (whence "calendar"), Kalendsfirst day of the month; it is thought to have originally been

the day of the new moon. According to some ancient or modern proposed etymologies of the word, it

was derived from the phrase kalo Iuno Covella or kalo Iuno Novella, meaning, respectively, "hollow

Juno I call you" and "new Juno I call you", an announcement about the Nones or in proclaiming the

new moon that marked the Kalends which the pontiffs made every first day of the month on the

Capitoline Hill in the Announcement Hall.[18]

Idus or Eidus, Idesthought to have originally been the day of the full moon, was the 15th day of

March, May, July, and October (the months with 31 days) and the 13th day of the others.

Nonae, Nonesthought to have originally been the day of the half moon. The Nones was eight days

before the Ides, and fell on the fifth or seventh day of the month, depending on the position of the

Ides. (Nones implies ninth from the Latin novem, because, counting Ides as first, one day before is the

second, and eight days before is the ninth).

The day preceding the Kalends, Nones, or Ides was Pridie, e.g., Prid. Id. Mart. = 14 March. Other days were

denoted by ordinal number, counting back from a named reference day. The reference day itself counted as

the first, so that two days before was denoted the third day. Dates were written as a.d. NN, an abbreviation

for ante diem NN, meaning "on the Nth (Numerus) day before the named reference day (Nomen)",[19] e.g.,

a.d. III Kal. Nov. = on the third day before the November Kalends = 30 October. The value two was not used

to denote a day before the fixed point, because second was the same as pridie. Further examples of date

equivalence are: a.d. IV Non. Jan. = 2 January; a.d. VI Non. Mai. = 2 May; a.d. VIII Id. Apr. = 6 April; a.d.

VIII Id. Oct. = 8 October; a.d. XVII Kal. Nov. = 16 October.

In detail, the system worked as follows:

Months were grouped in days such that the Kalends was the first day of the month, the Ides was the 13th day

of short months, or the 15th day of long months, and the Nones was the 9th day (counted inclusively) before

the Ides (i.e., the fifth or seventh day of the month). All other days of the month were counted backward

(inclusively) from these three dates. In both long and short months (except February and the mensis

intercalaris) there were 16 days between the Ides of the month and the Kalends of the next month, and the

date referred to the name of the next month, not that of the current month; thus, for example, the date of the

16th day of March was a.d. XVII Kal. Apr. In intercalary years, the first part of February was terminated on

the 23rd, i.e., the day of the Terminalia, and the festivals normally held in the last five days of February were

held instead in the last five days of the intercalary month, immediately before the Kalends of March. The

first 22 or 23 days of the intercalary month were inserted between these two parts.

So:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_calendar

Page 5 sur 12

Roman calendar - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

13/07/2016 11:17

In long months (31 daysMarch, May, July (Quintilis), and October), the days were divided into:

1st day of the month: 1 day for the Kalends of the month

2nd to 6th days of the month: 5 days before the Nones

7th day of the month: 1 day for the Nones

8th to 14th days of the month: 7 days before the Ides

15th day of the month: 1 day for the Ides

16th to 31st days of the month: 16 days before the Kalends of the next month

In short months (29 daysJanuary, April, June, August (Sextilis), September, November and

December), the days were divided into:

1st day of the month: 1 day for the Kalends of the month

2nd to 4th days of the month: 3 days before the Nones

5th day of the month: 1 day for the Nones

6th to 12th days of the month: 7 days before the Ides

13th day of the month: 1 day for the Ides

14th to 29th days of the month: 16 days before the Kalends of the next month

In ordinary years, the days in February (28 days) were divided into:

1st day of the month: 1 day for the Kalends of February

2nd to 4th days of the month: 3 days before the Nones

5th day of the month: 1 day for the Nones

6th to 12th days of the month: 7 days before the Ides

13th day of the month: 1 day for the Ides

14th to 28th days of the month: 15 days before the Kalends of March

In intercalary years, the days in February (23 days) were divided into:

1st day of the month: 1 day for the Kalends of February

2nd to 4th days of the month: 3 days before the Nones

5th day of the month: 1 day for the Nones

6th to 12th days of the month: 7 days before the Ides

13th day of the month: 1 day for the Ides

14th day onwards: counting down to a festival (see below) or to the Kalends of the intercalary

month

The days of the intercalary month inserted in intercalary years (27 days) were divided into:

1st day of the intercalary month: 1 day for the Kalends of the intercalary month

2nd to 4th days of the intercalary month: 3 days before the Nones

5th day of the intercalary month: 1 day for the Nones

6th to 12th days of the intercalary month: 7 days before the Ides

13th day of the intercalary month: 1 day for the Ides

14th day onwards: counting down to the Kalends of March

Some dates were also sometimes known by the name of a festival that occurred on them, or shortly

afterwards. Examples of such dates are recorded for the Feralia, Quirinalia, and the Terminalia, though not

yet for the Lupercalia. The known examples of such dates are all after the Ides of February, which suggests

they are connected with resolving an ambiguity that could arise in intercalary years: dates of the form a.d.

[N] Kal. Mart. were dates in late February in regular years, but were a month later in intercalary years.

However, it is much debated whether there was a fixed rule for using festival-based dates. It has been

variously proposed that a date like a.d. X Terminalia (known from an inscription in 94 BC) implied that its

year 'was', 'was not', or 'might have been' intercalary.

When Julius Caesar added days to some of the months, he added them to the end of the month, so as not to

disturb the dates of festivals in those months. This increased the count of all days after the Ides in those

months, and had some odd effects. For example, the emperor Augustus was born in 63 BC on the 23rd day

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_calendar

Page 6 sur 12

Roman calendar - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

13/07/2016 11:17

of September. In the pre-Julian calendar, this is seven days before the Kalends of October (or, in Roman

style, counting inclusively, a.d. VIII Kal. Oct.), but in the Julian calendar, it is eight days (a.d. IX Kal. Oct.).

Because of this ambiguity, his birthday was sometimes celebrated on both dates. See discussion in Julian

calendar.

Nundinal cycle

The Romans of the Republic, like the Etruscans, used a "market

week" of eight days, marked as A to H in the calendar. A nundinum

was the market day; etymologically, the word is related to novem,

"nine", because the Roman system of counting was inclusive. The

market "week" is the nundinal cycle. Since the length of the year was

not a multiple of eight days, the letter for the market day (known as a

"nundinal letter") changed every year. For example, if the letter for

market days in some year was A and the year was 355 days long,

then the letter for the next year would be F.

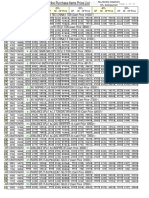

A fragment of the Fasti Praenestini

The nundinal cycle formed one rhythm of day-to-day Roman life; the

for the month of April (Aprilis),

market day was the day when country people would come to the city,

showing the nundinal letters on the

and the day when city people would buy their eight days' worth of

left edge

groceries. For this reason, a law was passed in 287 BC (the Lex

Hortensia) that forbade the holding of meetings of the comitia (for

example to hold elections) on market days, but permitted the holding of legal actions. In the late republic, a

superstition arose that it was unlucky to start the year with a market day (i.e., for the market day to fall on 1

January, with a letter A), and the pontiffs, who regulated the calendar, took steps to avoid it.

Because the nundinal cycle was absolutely fixed at eight days under the Republic, information about the

dates of market days is one of the most important tools used for working out the Julian equivalent of a

Roman date in the pre-Julian calendar. In the early Empire, the Roman market day was occasionally

changed. The details of this are not clear, but one likely explanation put forward is that it would be moved

by one day if it fell on the same day as the festival of Regifugium, an event that could occur at intervals of

three years. The reason for this movement has not been explained.

The nundinal cycle was eventually replaced by the modern seven-day week, which first came into use in

Italy during the early imperial period,[20] after the Julian calendar had come into effect in 45 BC. The system

of nundinal letters was also adapted for the week. (See dominical letter.) For a while, the week and the

nundinal cycle coexisted, but by the time the week was officially adopted by Constantine in AD 321, the

nundinal cycle had fallen out of use. For further information on the week, see week and days of the week.

Character of the day

Each day of the Roman calendar was marked on the fasti with a letter that designated its religious and legal

character. These were:[21]

F (fastus), days when it was legal to initiate action in the courts of civil law (dies fasti);

C (comitialis), a day on which the Roman people could hold assemblies (dies comitalis);

N (nefastus), when these political activities and the administration of justice were prohibited (dies

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_calendar

Page 7 sur 12

Roman calendar - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

13/07/2016 11:17

nefasti);

NP of elusive meaning, but marking feriae, public holidays (thought by some to mean nefastus priore,

"unlawful before noon", along with FP, fastus priore, "lawful before noon");

QRCF (perhaps for quando rex comitiavit fas,[22] "Permissible, when the king has entered the

comitium"), a day when it was religiously permissible for the rex (probably the priest known as the rex

sacrorum) to call for an assembly;[23]

EN (endotercissus, an archaic form of intercissus, "cut in half"), for days that were nefasti in the

morning, when sacrifices were being prepared, as well as in the evening, while sacrifices were being

offered, but were fasti in the middle of the day.

Years

The calendar year originally began on 1 March, as is shown by the

names of the six months following June (Quintilis = fifth month,

Sextilis = sixth month, September = seventh month, etc.). It is not

known when the start of the calendar year was changed to 1 January.

Ancient authors attributed it to Numa Pompilius. Varro states that,

according to M. Fulvius Nobilior (consul in 189 BC), who had

composed a commentary on a fasti preserved in the temple of Hercules

Musarum, January was named after Janus because the god faced both

ways, which implies the calendar year started in January in his time,

before the consular year started beginning on 1 January in 153 BC. A

surviving calendar from the late Republic proves the calendar year

started in January before the Julian reform.

How years were identified during the Roman monarchy is not known.

Fragment of an imperial-age

During the Roman Republic, years were named after the consuls, who

consular fasti, Museo Epigrafico,

were elected annually (see List of Republican Roman Consuls). Thus,

Rome

the name of the year identified a consular term of office, not a calendar

year. For example, 205 BC was "The year of the consulship of Publius

Cornelius Scipio Africanus and Publius Licinius Crassus", who took office on 15 March of that year, and

their consular year ran until 14 March 204 BC. Lists of consuls were maintained in the fasti.

The first day of the consular term changed several times during Roman history. The Senate changed it to 1

January in 153 BC in order to allow consul Quintus Fulvius Nobilior to attack the city of Segeda (in Aragon,

Spain) during the Celtiberian Wars.[24] Before then, it was 15 March. Earlier changes are a little less certain.

There is good reason to believe it was 1 May for most of the third century BC, until 222 BC. Livy mentions

earlier consular years starting on 1 Sextilis (August), 15 May, 15 December, 1 October and 1 Quintilis

(July).

In the later Republic, historians and scholars began to count years from the founding of the city of Rome.

Different scholars used different dates for this event. The date most widely used today is that calculated by

Varro, 753 BC, but other systems varied by up to several decades. Dates given by this method are numbered

ab urbe condita (meaning "from the founding of the city", and abbreviated AUC), and correspond to

consular years. When reading ancient works using AUC dates, care must be taken to determine the epoch

used by the author before translating the date into a Julian year.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_calendar

Page 8 sur 12

Roman calendar - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

13/07/2016 11:17

In parts of the Roman empire, it was common to date by the provincial year (anno prouinciarium, A.PP.). In

Roman Africa, year 1 was AD 39; in Hispania it was 38. Thus, to arrive at AD dates for Africa and Spain it

is necessary to add 39 and 38, respectively, to the provincial year. The Spanish provincial year was the basis

of the Spanish era, the dating system common throughout Spain during the Middle Ages.[25]

Extant fasti

A considerable number of inscribed calendars, or fasti, have been

discovered. The Praenestine calendar (Fasti praenestini), discovered

in 1770, arranged by the famous grammarian Verrius Flaccus,

contains the months of January, March, April, and December, and a

portion of February. The tablets give an account of festivals, and also

of the triumphs of Augustus and Tiberius. There are still two

complete calendars in existence, an official list by Philocalus (354),

and a Christian version of the official calendar, made by Polemius

Silvius (448).

Converting pre-Julian dates

A section of the Fasti Praenestini,

with the entry on the "Feast of

Robigo" (bottom right).

The fact that the modern world uses the same month names as the

Romans can lead to an erroneous assumption that a Roman date occurred on the same Julian date as its

modern equivalent. Even early Julian dates, before the leap year cycle was stabilised, are not quite what they

appear to be. For example, Macrobius says 45 BC was not a leap year.

Finding the exact Julian equivalent of a pre-Julian date is complex. As there exists an essentially complete

list of the consuls, a Julian year can be found to correspond to the pre-Julian year.

However, the sources rarely reveal which years were regular, which were intercalary, and how long an

intercalary year was. Nevertheless, the pre-Julian calendar could be substantially out of alignment with the

Julian calendar. Two precise astronomical synchronisms given by Livy show that in 168 BC, the two

calendars were misaligned by more than two months, and in 190 BC, they were four months out of

alignment.

A number of other clues are available to reconstruct the Julian equivalent of pre-Julian dates. First, the

precise Julian date for the start of the Julian calendar is known, although some uncertainty occurs even about

that. Detailed sources for the previous decade or so are found, mostly in the letters and speeches of Cicero.

Combining these with what is known about how the calendar worked, especially the nundinal cycle, an

accurate conversion of Roman dates after 58 BC relative to the start of the Julian calendar can be performed.

The histories of Livy give exact Roman dates for two eclipses in 190 BC and 168 BC, and a few loose

synchronisms to dates in other calendars provide rough (and sometimes exact) solutions for the intervening

period. Before 190 BC, the alignment between the Roman and Julian years is determined by clues such as

the dates of harvests mentioned in the sources.

Combining these sources of data, an estimate can be computed for approximate Julian equivalents of Roman

dates back to the start of the First Punic War in 264 BC. However, while there are enough data to make such

reconstructions, the number of years before 45 BC for which pre-Julian Roman dates can be converted to

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_calendar

Page 9 sur 12

Roman calendar - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

13/07/2016 11:17

Julian dates with certainty is very small, and several different reconstructions of the pre-Julian calendar are

possible. A detailed reconstruction giving conversions from pre-Julian dates into Julian dates is available.[26]

See also

Ab urbe condita

Ancient Rome

General Roman calendar (includes calendar of Roman Catholic saints)

Gregorian calendar

Julian calendar

Roman festivals

Notes

1. According to Livy, Numa's calendar was lunisolar with lunar months and several intercalary months spread over

nineteen years so that the Sun returned in the twentieth year to the same position it had in the first year. (Livy,

History of Rome (http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/etcbin/browse-mixed-new?id=Liv1His&tag=public&images=images/m

odeng&data=/texts/english/modeng/parsed) 1.19) (William Smith, A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities

(London: 1875) "Calendarium (http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/secondary/SMIGRA*/Calendar

ium.html)", Year of Numa)

2. This month name has also been attested as Quinctilis; see, for example, Bonnie Blackburn and Leofranc HolfordStrevens, The Oxford companion to the year, Oxford University Press, 1999, page 669.

3. Macrobius, Saturnalia, tr. Percival Vaughan Davies (New York: Columbia University Press, 1969), book I, chapters

1213, pp. 8995.

4. Hewitt Key, Thomas (1875). quoted in A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, auth: William Smith. London:

John Murray. pp. 223233. "With regard to the length of the months, Censorinus, Macrobius, and Solinus agree in

ascribing thirty-one days to four of them, called pleni menses; thirty to the rest called cavi menses."

5. Theodor Mommsen, History of Rome, Book I (http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/10701) chapter 14.

6. Plutarch, Life of Numa (http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Lives/Numa*.html#Romulan_

year) chapter 18.

7. Ovid, Fasti (http://www.tonykline.co.uk/PITBR/Latin/OvidFastiBkTwo.htm), tr. A. S. Kline (2004), Book II

(February), last eight lines of introduction.

8. Fowler, 1899, p. 5.

9. Lanfranchi, Thibaud (3 October 2013). " propos de la carrire de Cn. Flavius". Mlanges de lcole franaise de

Rome. Antiquit (125-1). doi:10.4000/mefra.1322.

10. Rotondi, 1912, p. 441

11. Macrobius, Saturnalia, 1.12

12. Censorinus, The Natal Day, 20.28, tr. William Maude, New York 1900, available at [1] (http://elfinspell.com/Classic

alTexts/Maude/Censorinus/DeDieNatale-Part2.html).

13. Macrobius, Saturnalia, 1.13 tr. Percival Vaughan Davies, New York 1969, Latin text at [2] (http://penelope.uchicago.

edu/Thayer/L/Roman/Texts/Macrobius/Saturnalia/1*.html#13).

14. Livy 45.44.3.

15. Livy 43.11.13.

16. Varro, On the Latin language, 6.13, tr. Roland Kent, London 1938, available at [3] (http://ryanfb.github.io/loebolus-d

ata/L333.pdf).

17. Michels, 1967.

18. Varro, Marcus Terentius (1938). "VI.27". De lingua latina [On the Latin Language]. Loeb Classical Library (in Latin

and English) I. Translated by Roland Grubb Kent. pp. 198201. At the Internet Archive. kalo or calo is a form of the

verb calare, meaning "to announce solemnly", "to call out"; see Harper, Douglas. "calendar". Online Etymology

Dictionary. calare (http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0059:entry=calo1). Charlton

T. Lewis and Charles Short. A Latin Dictionary on Perseus Project. See also Rpke, Jrg (2011). The Roman

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_calendar

Page 10 sur 12

Roman calendar - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

13/07/2016 11:17

Calendar from Numa to Constantine: Time, History, and the Fasti. Translated by David M.B. Richardson. John

Wiley & Sons. pp. 2425. At Google Books.

Syntax note: The Romans often inserted a phrase between a preposition and its noun, and here. a.d. III Kal. Nov.

(ante diem tertium Kalendas Novembres), ante governs Kalendas, and the literal meaning is 'on the third day' [diem

tertium accusative of time] 'before the November kalends' [the month name is an adjective in Latin]. In late Latin, the

'a.d.' was sometimes dropped in favor of an ablative construction.

Brind'Amour, 1983, p. 256275

Unless otherwise noted, the explanations of the following abbreviations are from H. H. Scullard, Festivals and

Ceremonies of the Roman Republic (Cornell University Press, 1981), pp. 4445.

On the basis of the Fasti Viae Lanza, which gives Q. Rex C. F.

Mommsen as summarized by Jrg Rpke, The Roman Calendar from Numa to Constantine: Time, History, and the

Fasti (WileyBlackwell, 2011), pp. 2627.

Francisco Burillo, Segeda and Rome. The historical development of a Celtiberian city-state (http://www.segeda.net/b

ibliografia/pdf/segeda_early.pdf)

Ralph W. Mathieson, People, Personal Expression, and Social Relations in Late Antiquity, vol. 2 (University of

Michigan, 2003), pp. 1415.

Roman Dates (http://www.tyndalehouse.com/Egypt/ptolemies/chron/roman/chron_rom_intro_fr.htm)

References

Brind'Amour, P. Le Calendrier romain: Recherches chronologiques (Ottawa, 1983).

Fowler, W. Warde. The Roman festivals of the period of the Republic; an introduction to the study of

the religion of the Romans (London and New York: Macmillan and Co, 1899)

Macrobius, Saturnalia (online) (http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/L/Roman/Texts/Macrobius/Satur

nalia/1*.html).

Michels, A. K. The Calendar of the Roman Republic (Princeton, 1967).

Rotondi, Giovanni. Leges publicae populi romani (Milan: Societ editrice libraria, 1912).

Rpke, J. The Roman Calendar from Numa to Constantine: Time, History and the Fasti (trans. D. M.

B. Richardson) (Wiley, 2011). ISBN 978-0-470-65508-5 (print) 9781444396539 (online) (http://online

library.wiley.com/book/10.1002/9781444396539).

Further reading

Bickerman, E. J. Chronology of the Ancient World. (London: Thames & Hudson, 1969, rev. ed. 1980).

Feeney, Denis C. Caesar's Calendar: Ancient Time and the Beginnings of History. Berkeley:

University of California Press, 2007 (hardcover, ISBN 0-520-25119-9).

Richards, E. G. Mapping Time. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-850413-6.

External links

Early Roman Calendar History (http://webexhibits.org/calendars/calendar-roman.html)

James Grout: The Roman Calendar, part of the Encyclopdia Romana (http://penelope.uchicago.edu/

~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/calendar/romancalendar.html)

Roman Dates (Chris Bennett's site) (http://www.tyndalehouse.com/Egypt/ptolemies/chron/roman/chro

n_rom_intro_fr.htm)

Smith's Dictionary article (http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/secondary/SMIGRA*

/Calendarium.html)

Plutarch: excerpt from Numa Pompilius (http://www.webexhibits.org/calendars/year-text-Plutarch.htm

l)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_calendar

Page 11 sur 12

Roman calendar - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

13/07/2016 11:17

Retrieved from "https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Roman_calendar&oldid=725150094"

Categories: Roman calendar

This page was last modified on 13 June 2016, at 21:44.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may

apply. By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Wikipedia is a registered

trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_calendar

Page 12 sur 12

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- 4 of July, Star Sirius, Yahweh, and The Vedic NakshatrasDocument18 pages4 of July, Star Sirius, Yahweh, and The Vedic NakshatrasEce AyvazPas encore d'évaluation

- Months of The Jewish YearDocument28 pagesMonths of The Jewish YearBayan Chem-boy MnnahPas encore d'évaluation

- Roman NumeralsDocument10 pagesRoman NumeralsBiju100% (2)

- Lunar CalendarsDocument9 pagesLunar CalendarsGary WadePas encore d'évaluation

- Origin of The Calendar and The Church YearDocument7 pagesOrigin of The Calendar and The Church YearIfechukwu U. IbemePas encore d'évaluation

- Indian CalendarDocument49 pagesIndian Calendararavindiyengar1977Pas encore d'évaluation

- Jewish CalendarDocument6 pagesJewish CalendarJewish home100% (6)

- Vetius Valens and The Planetary WeekDocument28 pagesVetius Valens and The Planetary Weekceudekarnak100% (1)

- SSL2 - ColoringPages - LatinDocument184 pagesSSL2 - ColoringPages - Latinsusanap_20Pas encore d'évaluation

- Coptic CalenderDocument29 pagesCoptic CalenderRicardo Kuptios100% (1)

- Constantine Changed CalendarDocument7 pagesConstantine Changed CalendarSharalom Ban Yah0% (1)

- Jewish CalendarDocument5 pagesJewish Calendarapi-259626831Pas encore d'évaluation

- CH 6 Pondering Egyptian Calendar DepictionsDocument18 pagesCH 6 Pondering Egyptian Calendar DepictionsmaiPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is So Right About The Hindu CalendarDocument9 pagesWhat Is So Right About The Hindu CalendarRakhi PatwaPas encore d'évaluation

- ''A Grammar of Southern Yauyos Quechua'' (Aviva Shimelman, 2014)Document206 pages''A Grammar of Southern Yauyos Quechua'' (Aviva Shimelman, 2014)Thriw100% (1)

- Egyptian Religious Calendar-CDXIII Great Year of Ra Wp-RenepetDocument23 pagesEgyptian Religious Calendar-CDXIII Great Year of Ra Wp-RenepetRafael Ramesses75% (4)

- Pagan Origins of Modern CalendarDocument49 pagesPagan Origins of Modern CalendarTerra SmithPas encore d'évaluation

- Calendar - WikipediaDocument47 pagesCalendar - WikipediaAmalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Jewish CalendarDocument9 pagesJewish CalendarRecuperatedbyJesusPas encore d'évaluation

- Co-Regency of Augustus and Tiberius Caused 2 Years Error in Redating Herod's Death From 1 BC To 4 BCDocument18 pagesCo-Regency of Augustus and Tiberius Caused 2 Years Error in Redating Herod's Death From 1 BC To 4 BCEulalio EguiaPas encore d'évaluation

- 7th Level Practice SheetDocument9 pages7th Level Practice SheetGirish JhaPas encore d'évaluation

- ''Ainu For Beginners'' (Unilang, 2009)Document48 pages''Ainu For Beginners'' (Unilang, 2009)Thriw100% (1)

- The Calendars of Ancient Egypt: BCE BCEDocument22 pagesThe Calendars of Ancient Egypt: BCE BCERobert DavisPas encore d'évaluation

- Grace Amadon - Crucifixion Date, and Astronomical Soundness of October 22, 1844Document34 pagesGrace Amadon - Crucifixion Date, and Astronomical Soundness of October 22, 1844Brendan Paul Valiant100% (3)

- Byzantine CalendarDocument16 pagesByzantine CalendarFilipPas encore d'évaluation

- 5th Level Practice SheetDocument9 pages5th Level Practice SheetGirish Jha50% (2)

- ''Noqu Vosa Me'u Bula Taka - Fijian Language Week'' (Ministry For Pacific Peoples, 2016)Document17 pages''Noqu Vosa Me'u Bula Taka - Fijian Language Week'' (Ministry For Pacific Peoples, 2016)Thriw100% (1)

- God's Sacred Calendar Part 2Document9 pagesGod's Sacred Calendar Part 2joePas encore d'évaluation

- A History of The New YearDocument2 pagesA History of The New YearMarjan TrajkovicPas encore d'évaluation

- The Liturgical Calendars of Israel - Hubert - LunsDocument3 pagesThe Liturgical Calendars of Israel - Hubert - LunsHubert LunsPas encore d'évaluation

- 2nd Level Practice SheetDocument9 pages2nd Level Practice SheetJaiswal Meenu76% (17)

- Babylonian CalendarDocument4 pagesBabylonian Calendarprevo015100% (1)

- Analysis of Sacred ChronologyDocument129 pagesAnalysis of Sacred ChronologyovidiuvictorPas encore d'évaluation

- The Roman Festivals of the Period of the Republic: An Introduction to the Study of the Religion of the RomansD'EverandThe Roman Festivals of the Period of the Republic: An Introduction to the Study of the Religion of the RomansPas encore d'évaluation

- History of CalendarsDocument12 pagesHistory of Calendarsjohn100% (1)

- Mathopedia Abacus Competiation Sample PapperDocument60 pagesMathopedia Abacus Competiation Sample PapperPRASH91% (11)

- Ra QP 209 Indian AbacusDocument9 pagesRa QP 209 Indian AbacusIndian AbacusPas encore d'évaluation

- Quest For The Right DateDocument7 pagesQuest For The Right DatekhenedPas encore d'évaluation

- Dionysius Exiguus and The Introduction of The Christian EraDocument82 pagesDionysius Exiguus and The Introduction of The Christian EraneddyteddyPas encore d'évaluation

- Origin of Names of Days Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday SaturdayDocument9 pagesOrigin of Names of Days Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturdayjoydeep_d3232Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Evolution of The Roman Calendar: Past Imperfect 15 (2009) - © - ISSN 1711-053X - eISSN 1718-4487Document32 pagesThe Evolution of The Roman Calendar: Past Imperfect 15 (2009) - © - ISSN 1711-053X - eISSN 1718-4487PatriBronchalesPas encore d'évaluation

- How Come February Has Only 28 DaysDocument5 pagesHow Come February Has Only 28 DaysNoman AhmadPas encore d'évaluation

- Days and MonthsDocument3 pagesDays and MonthsDiphilusPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Does February Have Only 28 DaysDocument1 pageWhy Does February Have Only 28 DaysManas SrivastavaPas encore d'évaluation

- Panchanga IntroductionDocument16 pagesPanchanga IntroductionSandhya KadamPas encore d'évaluation

- Calendars and Assumptions: Hebrew For ChristiansDocument5 pagesCalendars and Assumptions: Hebrew For ChristiansShanica Paul-RichardsPas encore d'évaluation

- ST ST ST ST ST STDocument5 pagesST ST ST ST ST STDevin MaghenPas encore d'évaluation

- Chinese Calendar: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument18 pagesChinese Calendar: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaBanko PironkovPas encore d'évaluation

- How Old is the World the Byzantine Era Κατὰ Ῥωμαίους and Its RivalsDocument5 pagesHow Old is the World the Byzantine Era Κατὰ Ῥωμαίους and Its RivalsAnita TheredPas encore d'évaluation

- A History of The MonthsDocument4 pagesA History of The MonthsMuhammed Surajudeen Olasupo AminuPas encore d'évaluation

- Gregorian Calendar History From Wikipedia 2009Document24 pagesGregorian Calendar History From Wikipedia 2009ناسک اتمانPas encore d'évaluation

- History of The CalendarDocument4 pagesHistory of The Calendaranon-500003Pas encore d'évaluation

- Leap YearDocument20 pagesLeap YearInsaf BhattiPas encore d'évaluation

- Paper 12Document12 pagesPaper 12tPas encore d'évaluation

- Roman CalendarDocument3 pagesRoman CalendarVitafelicePas encore d'évaluation

- Thermal Energy 1Document22 pagesThermal Energy 1patrick clarkePas encore d'évaluation

- Istory of The Months and The Meanings of Their NamesDocument10 pagesIstory of The Months and The Meanings of Their NamesjardelPas encore d'évaluation

- Time Days Months SeasonsDocument6 pagesTime Days Months SeasonsBalint PaulPas encore d'évaluation

- 0 (Year) : Counting Intervals Without A ZeroDocument9 pages0 (Year) : Counting Intervals Without A ZeroAnonymous OuZdlEPas encore d'évaluation

- Maria Kathina D. Crave BSN-3CDocument1 pageMaria Kathina D. Crave BSN-3CTharina SalvatorePas encore d'évaluation

- Calendars: Months From The Moon and Years From The SunDocument2 pagesCalendars: Months From The Moon and Years From The Sunabdel2121Pas encore d'évaluation

- Calendar: HistoryDocument27 pagesCalendar: HistorysurbcPas encore d'évaluation

- The Latin Calendar PDFDocument2 pagesThe Latin Calendar PDFThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- "Historical" Dates in Medieval Liturgical Calendars: OutlineDocument22 pages"Historical" Dates in Medieval Liturgical Calendars: OutlinejigasPas encore d'évaluation

- AloyDocument2 pagesAloyroman232323Pas encore d'évaluation

- Related Articles: Want To Read More Articles About Jewish Holidays?Document5 pagesRelated Articles: Want To Read More Articles About Jewish Holidays?shibly anastasPas encore d'évaluation

- The First Visible Crescent Does NOT Announce The New MoonDocument6 pagesThe First Visible Crescent Does NOT Announce The New MoonCraig KirkPas encore d'évaluation

- Calendar IntroDocument9 pagesCalendar IntroMarceloPas encore d'évaluation

- ''Deure'' in Catalan (Wiktionary)Document2 pages''Deure'' in Catalan (Wiktionary)ThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- ''PRDocument4 pages''PRThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- Cretan Hieroglyphs (Wikipedia)Document5 pagesCretan Hieroglyphs (Wikipedia)ThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- ''Anbani'' - Georgian AlphabetsDocument6 pages''Anbani'' - Georgian AlphabetsThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- Active-Stative Language (Wikipedia)Document5 pagesActive-Stative Language (Wikipedia)ThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- ''Anbani'' - Georgian AlphabetsDocument6 pages''Anbani'' - Georgian AlphabetsThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- ''Unknown Language Discovered in Malaysia''Document2 pages''Unknown Language Discovered in Malaysia''ThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- ''Ayrampu'' in Quechua (Wiktionary)Document4 pages''Ayrampu'' in Quechua (Wiktionary)ThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- ''Complector'' in Latin (Wiktionary)Document2 pages''Complector'' in Latin (Wiktionary)ThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- ''Burushaski Morphology'' (Eisenbrauns, 2007)Document44 pages''Burushaski Morphology'' (Eisenbrauns, 2007)ThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- ''Čáppat'' in Northern Sami (Wiktionary)Document2 pages''Čáppat'' in Northern Sami (Wiktionary)ThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- Austral Language (Wikipedia)Document1 pageAustral Language (Wikipedia)ThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- ''In A While'' vs. ''For A While'' in EnglishDocument3 pages''In A While'' vs. ''For A While'' in EnglishThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- ''Burushaski Morphology'' (Eisenbrauns, 2007)Document44 pages''Burushaski Morphology'' (Eisenbrauns, 2007)ThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- ''Want To Learn To Speak Latin or Greek This (2018) Summer''Document10 pages''Want To Learn To Speak Latin or Greek This (2018) Summer''ThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- ''Čáppat'' in Northern Sami (Wiktionary)Document2 pages''Čáppat'' in Northern Sami (Wiktionary)ThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- ''Ioma-Ghlac'' in Scottish Gaelic (Wiktionary) PDFDocument1 page''Ioma-Ghlac'' in Scottish Gaelic (Wiktionary) PDFThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- ''Complector'' in Latin (Wiktionary)Document2 pages''Complector'' in Latin (Wiktionary)ThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 CardarDocument62 pages5 CardarAlexsandra MouraPas encore d'évaluation

- ''Ayą́'' in Navajo (Wiktionary)Document2 pages''Ayą́'' in Navajo (Wiktionary)ThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- ''Chiliogrammum'' in Latin (Wiktionary)Document1 page''Chiliogrammum'' in Latin (Wiktionary)ThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- ''Čáppat'' in Northern Sami (Wiktionary)Document2 pages''Čáppat'' in Northern Sami (Wiktionary)ThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- ''Edō'' & ''Ēdō'' in Latin (Wiktionary)Document5 pages''Edō'' & ''Ēdō'' in Latin (Wiktionary)ThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- ''Burushaski Morphology'' (Eisenbrauns, 2007)Document44 pages''Burushaski Morphology'' (Eisenbrauns, 2007)ThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- ''Ayą́'' in Navajo (Wiktionary)Document2 pages''Ayą́'' in Navajo (Wiktionary)ThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- ''Ioma-Ghlac'' in Scottish Gaelic (Wiktionary)Document1 page''Ioma-Ghlac'' in Scottish Gaelic (Wiktionary)ThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- ''Ayrampu'' in Quechua (Wiktionary)Document4 pages''Ayrampu'' in Quechua (Wiktionary)ThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- Cheatsheet PDFDocument2 pagesCheatsheet PDFSamplerjPas encore d'évaluation

- Star Rating List For Room Air ConditionersDocument64 pagesStar Rating List For Room Air ConditionersAshish Aggarwal100% (3)

- Indian School Al Wadi Al Kabir: Rounding Off Numbers & Roman NumeralsDocument3 pagesIndian School Al Wadi Al Kabir: Rounding Off Numbers & Roman Numeralspatmos666Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sant Tukaram National Model, Latur: Chapter-3.2 Roman NumeralsDocument2 pagesSant Tukaram National Model, Latur: Chapter-3.2 Roman NumeralsAbhay DaithankarPas encore d'évaluation

- Is QP 2 Indian AbacusDocument5 pagesIs QP 2 Indian Abacusneo shahPas encore d'évaluation

- Roman CalendarDocument3 pagesRoman CalendarVitafelicePas encore d'évaluation

- Roman Calendar (Wikipedia)Document12 pagesRoman Calendar (Wikipedia)ThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- PriceListHirePurchase Normal 1Document55 pagesPriceListHirePurchase Normal 1Muhammad HajiPas encore d'évaluation

- Compound Wall Calculations-1Document20 pagesCompound Wall Calculations-1k v rajeshPas encore d'évaluation

- 8th Level Practice Sheet PDFDocument9 pages8th Level Practice Sheet PDFsuranjanacPas encore d'évaluation

- Exercises # 1 Roman NumeralsDocument27 pagesExercises # 1 Roman NumeralsJuliah Katrina Yndra FernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- The Latin Calendar PDFDocument2 pagesThe Latin Calendar PDFThriwPas encore d'évaluation

- PriceListHirePurchase Normal 4 PDFDocument55 pagesPriceListHirePurchase Normal 4 PDFAbdul SamadPas encore d'évaluation

- PriceListHirePurchase NormalDocument54 pagesPriceListHirePurchase NormalAfzaal AwanPas encore d'évaluation

- Time of The Day: Prima Diei Hora (The First Hour of The Day) vs. Prima Noctis Hora (The First Hour of The Night)Document5 pagesTime of The Day: Prima Diei Hora (The First Hour of The Day) vs. Prima Noctis Hora (The First Hour of The Night)magistramccawleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Tabla de Números Romanos PDFDocument7 pagesTabla de Números Romanos PDFAriel Perez100% (1)

- PriceListHirePurchase Normal 9Document55 pagesPriceListHirePurchase Normal 9alvi ursPas encore d'évaluation

- A History of The Months and The Meanings of Their Names PDFDocument4 pagesA History of The Months and The Meanings of Their Names PDFmejaivasPas encore d'évaluation

- Roman Numbers Without Answers Year 6Document13 pagesRoman Numbers Without Answers Year 6nehal ismailPas encore d'évaluation

- HP PricelistDocument55 pagesHP PricelistfaisalPas encore d'évaluation

- PriceListHirePurchase Normal6thNov2019Document56 pagesPriceListHirePurchase Normal6thNov2019Jamil AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Getting Started With OneDriveDocument41 pagesGetting Started With OneDriveAijaz Ahmed ShaikhPas encore d'évaluation

- Roman NumeralsDocument7 pagesRoman NumeralsMuhammad Zahid100% (1)