Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Philippines Bank of Communications Vs CA

Transféré par

Elah ViktoriaTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Philippines Bank of Communications Vs CA

Transféré par

Elah ViktoriaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

PHILIPPINES BANK OF COMMUNICATIONS vs. HON.

COURT OF

APPEALS

G.R. No. 115678. February 23, 2001

YNARES-SANTIAGO, J.:

FACTS:

The case commenced with the filing by petitioner, on April 8, 1991, of

a Complaint against private respondent Bernardino Villanueva, private

respondent Filipinas Textile Mills and one Sochi Villanueva (now deceased)

before the Regional Trial Court of Manila. In the said Complaint, petitioner

sought the payment of P2,244,926.30 representing the proceeds or value of

various textile goods, the purchase of which was covered by irrevocable

letters of credit and trust receipts executed by petitioner with private

respondent Filipinas Textile Mills as obligor; which, in turn, were covered

by surety agreements executed by private respondent Bernardino Villanueva

and Sochi Villanueva. In their Answer, private respondents admitted the

existence of the surety agreements and trust receipts but countered that they

had already made payments on the amount demanded and that the interest

and other charges imposed by petitioner were onerous.

petitioner filed a Motion for Attachment,4 contending that violation of the

trust receipts law constitutes estafa, thus providing ground for the issuance

of a writ of preliminary attachment; specifically under paragraphs "b" and

"d," Section 1, Rule 57 of the Revised Rules of Court. Petitioner further

claimed that attachment was necessary since private respondents were

disposing of their properties to its detriment as a creditor. Finally, petitioner

offered to post a bond for the issuance of such writ of attachment.

The Motion was duly opposed by private respondents and, after the filing of

a Reply thereto by petitioner, the lower court issued its August 11, 1993

Order for the issuance of a writ of preliminary attachment, conditioned upon

the filing of an attachment bond. Following the denial of the Motion for

Reconsideration filed by private respondent Filipinas Textile Mills, both

private respondents filed separate petitions for certiorari before respondent

Court assailing the order granting the writ of preliminary attachment.

ISSUE: WON the lower court erred in issuing the writ of preliminary

attachment.

RULING:

Section 1 (b) and (d), Rule 57 of the then controlling Revised Rules of

Court, provides, to wit

SECTION 1. Grounds upon which attachment may issue. A plaintiff or any

proper party may, at the commencement of the action or at any time

thereafter, have the property of the adverse party attached as security for the

satisfaction of any judgment that may be recovered in the following cases:

xxx

xxx

xxx

(b) In an action for money or property embezzled or fraudulently misapplied

or converted to his us by a public officer, or an officer of a corporation, or an

attorney, factor, broker, agent or clerk, in the course of his employment as

such, or by any other person in a fiduciary capacity, or for a willful violation

of duty;

xxx

xxx

xxx

(d) In an action against a party who has been guilty of fraud in contracting

the debt or incurring the obligation upon which the action is brought, or in

concealing or disposing of the property for the taking, detention or

conversion of which the action is brought;

xxx

xxx

xxx

While the Motion refers to the transaction complained of as involving trust

receipts, the violation of the terms of which is qualified by law as

constituting estafa, it does not follow that a writ of attachment can and

should automatically issue. Petitioner cannot merely cite Section 1(b) and

(d), Rule 57, of the Revised Rules of Court, as mere reproduction of the

rules, without more, cannot serve as good ground for issuing a writ of

attachment. An order of attachment cannot be issued on a general averment,

such as one ceremoniously quoting from a pertinent rule.

Again, it lacks particulars upon which the court can discern whether or not a

writ of attachment should issue.

Petitioner cannot insist that its allegation that private respondents failed to

remit the proceeds of the sale of the entrusted goods nor to return the same is

sufficient for attachment to issue. We note that petitioner anchors its

application upon Section 1(d), Rule 57. This particular provision was

adequately explained in Liberty Insurance Corporation v. Court of

Appealsas follows

To sustain an attachment on this ground, it must be shown that the

debtor in contracting the debt or incurring the obligation intended to

defraud the creditor. The fraud must relate to the execution of the

agreement and must have been the reason which induced the other

party into giving consent which he would not have otherwise given.

To constitute a ground for attachment in Section 1 (d), Rule 57 of the

Rules of Court, fraud should be committed upon contracting the

obligation sued upon. A debt is fraudulently contracted if at the

time of contracting it the debtor has a preconceived plan or

intention not to pay, as it is in this case. Fraud is a state of mind and

need not be proved by direct evidence but may be inferred from the

circumstances attendant in each case (Republic v. Gonzales, 13 SCRA

633). (Emphasis ours)

SC find an absence of factual allegations as to how the fraud alleged

by petitioner was committed. As correctly held by respondent Court of

Appeals, such fraudulent intent not to honor the admitted obligation cannot

be inferred from the debtor's inability to pay or to comply with the

obligations.9 On the other hand, as stressed, above, fraud may be gleaned

from a preconceived plan or intention not to pay. This does not appear to be

so in the case at bar. In fact, it is alleged by private respondents that out of

the total P419,613.96 covered by the subject trust receipts, the amount of

P400,000.00 had already been paid, leaving only P19,613.96 as balance.

Hence, regardless of the arguments regarding penalty and interest, it can

hardly be said that private respondents harbored a preconceived plan or

intention not to pay petitioner.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- G.R. No. 115678Document3 pagesG.R. No. 115678Norma BayonetaPas encore d'évaluation

- Yu v. CA Digest Rule 58Document3 pagesYu v. CA Digest Rule 58Izo BellosilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Chavez v. CA, G.R. No. 174356, January 20, 2010Document2 pagesChavez v. CA, G.R. No. 174356, January 20, 2010Dara CompuestoPas encore d'évaluation

- Calo Vs RoldanDocument3 pagesCalo Vs RoldanHey it's RayaPas encore d'évaluation

- CFI Judge Oversteps Authority in Appointing ReceiverDocument2 pagesCFI Judge Oversteps Authority in Appointing ReceiverGilbert Yap100% (1)

- Siok Ping Tang VS Subic BayDocument3 pagesSiok Ping Tang VS Subic Bayfermo ii ramos100% (1)

- G.R. No. 173192 Land Dispute CaseDocument1 pageG.R. No. 173192 Land Dispute CaseLovelle Marie RolePas encore d'évaluation

- 9) Martelino v. NHMFC (Digest)Document2 pages9) Martelino v. NHMFC (Digest)Tini Guanio100% (1)

- FIRST AQUA SUGAR TRADERS Vs BPIDocument1 pageFIRST AQUA SUGAR TRADERS Vs BPIArlene DurbanPas encore d'évaluation

- Casalla Vs PeopleDocument3 pagesCasalla Vs PeopleIvan Montealegre Conchas100% (1)

- Case DigestDocument5 pagesCase DigestPevi Mae JalipaPas encore d'évaluation

- Vera vs. Rigor, G.R. No. 147377, August 10, 2007Document2 pagesVera vs. Rigor, G.R. No. 147377, August 10, 2007claire beltranPas encore d'évaluation

- Martelino V NHMF CorpDocument2 pagesMartelino V NHMF CorpDexter GasconPas encore d'évaluation

- Hyatt v. Ley Construction ruling on deposition-takingDocument6 pagesHyatt v. Ley Construction ruling on deposition-takingangelo prietoPas encore d'évaluation

- Rule 57 - My Digests - ProvremDocument34 pagesRule 57 - My Digests - Provrembebs CachoPas encore d'évaluation

- Torres Vs SpecializedDocument1 pageTorres Vs SpecializedJelaine Añides100% (1)

- 04) Sumulong V CADocument2 pages04) Sumulong V CAAlfonso Miguel LopezPas encore d'évaluation

- B5 - Pine City Educational vs. NLRC, GR No. 96779Document1 pageB5 - Pine City Educational vs. NLRC, GR No. 96779Luds OretoPas encore d'évaluation

- RTC Decision Appeal Period Motion for New TrialDocument2 pagesRTC Decision Appeal Period Motion for New TrialFrinz CastilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Casalla vs. PeopleDocument2 pagesCasalla vs. PeopleJoan Eunise FernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 - Macawiwili Gold Mining V CA - Digest - July 24Document1 page2 - Macawiwili Gold Mining V CA - Digest - July 24ESPERANZA TAYAMORAPas encore d'évaluation

- Pedro Sepulveda, SR vs. Atty. Pacifico S. PelaezDocument1 pagePedro Sepulveda, SR vs. Atty. Pacifico S. PelaezFelizardo I RomanoPas encore d'évaluation

- IV. 3. de Dios Vs CADocument2 pagesIV. 3. de Dios Vs CAJoshua Quentin TarceloPas encore d'évaluation

- LU YM V Mahinay-1Document2 pagesLU YM V Mahinay-1MilesPas encore d'évaluation

- Insurance Summons CaseDocument6 pagesInsurance Summons CaseSyElfredGPas encore d'évaluation

- Rule 9 PDFDocument16 pagesRule 9 PDFJanila BajuyoPas encore d'évaluation

- Virra Mall Tenants Association Inc Vs Virra Mall Greenhills AssociationDocument1 pageVirra Mall Tenants Association Inc Vs Virra Mall Greenhills AssociationCarlyn Belle de GuzmanPas encore d'évaluation

- 15 15. Garcia vs. Court of Appeals, Et - Al. (G.R. No. L-14758, March 30, 1962)Document2 pages15 15. Garcia vs. Court of Appeals, Et - Al. (G.R. No. L-14758, March 30, 1962)ChiiBiiPas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. 164255 - DigestDocument2 pagesG.R. No. 164255 - DigestEdmund Pulvera Valenzuela IIPas encore d'évaluation

- Llana's Supermarket Vs NLRCDocument3 pagesLlana's Supermarket Vs NLRCMary Joy NavajaPas encore d'évaluation

- Castro Vs Guevarra CivproDocument1 pageCastro Vs Guevarra CivprokeithnavaltaPas encore d'évaluation

- 9 - Sime Darby vs. NLRC - DigestDocument3 pages9 - Sime Darby vs. NLRC - DigestVanessaPas encore d'évaluation

- Que V CaDocument2 pagesQue V CaElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Digest by Mark Lorenz E. AlamaresDocument2 pagesCase Digest by Mark Lorenz E. AlamaresMark Lorenz AlamaresPas encore d'évaluation

- GR No. 191590Document3 pagesGR No. 191590.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Digest - Spouses Villuga v. Kelly HardwareDocument2 pagesDigest - Spouses Villuga v. Kelly HardwareLorenzo Elegio IIIPas encore d'évaluation

- EMAS Rule 3 Sustiguer V TamayoDocument2 pagesEMAS Rule 3 Sustiguer V TamayoKinitDelfinCelestialPas encore d'évaluation

- Balangcad Vs Justices of CA DigestDocument2 pagesBalangcad Vs Justices of CA DigestMarilou GaralPas encore d'évaluation

- DIGEST Rule 2 No. 3 Soloil v. Philippine Coconut AuthorityDocument4 pagesDIGEST Rule 2 No. 3 Soloil v. Philippine Coconut AuthorityRomnick Jesalva100% (1)

- Tillson VsDocument13 pagesTillson VsChelle OngPas encore d'évaluation

- Fortune Corporation vs. CADocument1 pageFortune Corporation vs. CAJonathan Bacus100% (1)

- Legal Memo 66 71Document29 pagesLegal Memo 66 71JoVic2020Pas encore d'évaluation

- Wang Lab jurisdiction case on service of summons through exclusive distributorDocument2 pagesWang Lab jurisdiction case on service of summons through exclusive distributorMikee Angela Panopio100% (1)

- Cuartero V CADocument3 pagesCuartero V CAiptrinidadPas encore d'évaluation

- 42 Springfield V Judge RTCDocument3 pages42 Springfield V Judge RTCPaolo SomeraPas encore d'évaluation

- Pcib Vs AlejandroDocument2 pagesPcib Vs AlejandroRap Patajo100% (1)

- BA Finance Corporation vs. Court of AppealsDocument1 pageBA Finance Corporation vs. Court of AppealsTon Ton CananeaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gonzales Vs Pe DigestDocument2 pagesGonzales Vs Pe DigestCess LintagPas encore d'évaluation

- DAR Vs Callejo - EdDocument2 pagesDAR Vs Callejo - EdJOHAYNIEPas encore d'évaluation

- Republic Vs Garcia Case DigestDocument3 pagesRepublic Vs Garcia Case DigestEva Trinidad100% (2)

- EMAS - Rule 3 - Sustiguer v. TamayoDocument2 pagesEMAS - Rule 3 - Sustiguer v. TamayoApollo Glenn C. EmasPas encore d'évaluation

- Case 1Document4 pagesCase 1Jong PerrarenPas encore d'évaluation

- Davao Light v. CA DigestDocument3 pagesDavao Light v. CA Digestkathrynmaydeveza100% (1)

- Office of The Ombudsman Vs Ibay - G.R. No. 137538. September 3, 2001Document5 pagesOffice of The Ombudsman Vs Ibay - G.R. No. 137538. September 3, 2001Ebbe DyPas encore d'évaluation

- III - Rule 116 (3) Virata V SandiganbayanDocument5 pagesIII - Rule 116 (3) Virata V SandiganbayanBananaPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Digest For CivProDocument16 pagesCase Digest For CivProReina Anne JaymePas encore d'évaluation

- HEIRS OF TABIA v. CADocument2 pagesHEIRS OF TABIA v. CACeedee RagayPas encore d'évaluation

- PBCOM Vs CADocument5 pagesPBCOM Vs CAPearl Deinne Ponce de LeonPas encore d'évaluation

- Digested SCAPR Cases 1Document18 pagesDigested SCAPR Cases 1R Ann JSPas encore d'évaluation

- SCARP Case/sDocument74 pagesSCARP Case/sR Ann JSPas encore d'évaluation

- Lapse of Motion for Reconsideration in Court RulingsDocument1 pageLapse of Motion for Reconsideration in Court RulingsElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- CA upholds annulment of deed transfer in property disputeDocument5 pagesCA upholds annulment of deed transfer in property disputeElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- PRETERITION - Advance Legitime - CollationDocument3 pagesPRETERITION - Advance Legitime - CollationElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Savings Tracker Template for GoalsDocument1 pageSavings Tracker Template for GoalsElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Monthly Budget Planner Template Elegant Minimalist Finance PlannerDocument1 pageMonthly Budget Planner Template Elegant Minimalist Finance PlannerElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Bill Tracker Monthly Expenses ListDocument1 pageBill Tracker Monthly Expenses ListElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Month Calendar TemplateDocument1 pageMonth Calendar TemplateElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Minimalist Modern Red Grey 2023 CalendarDocument12 pagesMinimalist Modern Red Grey 2023 CalendarElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Monthly Budget Planner Template Elegant Minimalist Finance PlannerDocument1 pageMonthly Budget Planner Template Elegant Minimalist Finance PlannerElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Extrajudicial Settlement of Estate TemplateDocument4 pagesExtrajudicial Settlement of Estate Templateblue13_fairy100% (1)

- Spouses Buenaventura V CADocument1 pageSpouses Buenaventura V CAElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Versatile, Modern Printed Planner Calendar For The MonthDocument1 pageVersatile, Modern Printed Planner Calendar For The MonthElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Rebecca Viado Non V CADocument2 pagesRebecca Viado Non V CAElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Spouses Buenaventura V CADocument1 pageSpouses Buenaventura V CAElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Nacar V NistalDocument2 pagesNacar V NistalElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Alvarez V IacDocument2 pagesAlvarez V IacElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Maloles V PhilipsDocument2 pagesMaloles V PhilipsElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Riofero V CADocument2 pagesRiofero V CAElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- 10.G.R. No. L-68053Document2 pages10.G.R. No. L-68053Elah Viktoria100% (1)

- Dismissal of complaint improperDocument2 pagesDismissal of complaint improperElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Facts:: Pamplona vs. Moreto G.R. No. L-33187 - March 31, 1980 Ponente: J. GuerreroDocument2 pagesFacts:: Pamplona vs. Moreto G.R. No. L-33187 - March 31, 1980 Ponente: J. GuerreroElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Rivera V RiveraDocument2 pagesRivera V RiveraElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- PP V KellyDocument2 pagesPP V KellyElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Mendoza V de Los SantosDocument3 pagesMendoza V de Los SantosElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gonzales V CifDocument4 pagesGonzales V CifElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- 1.G.R. No. 126334Document2 pages1.G.R. No. 126334Elah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Mendoza V de Los SantosDocument3 pagesMendoza V de Los SantosElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- 9.G.R. No. L-25049Document2 pages9.G.R. No. L-25049Elah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gonzales V CifDocument4 pagesGonzales V CifElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Court rules on estate inheritance disputeDocument3 pagesCourt rules on estate inheritance disputeElah ViktoriaPas encore d'évaluation

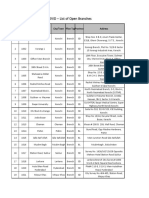

- List of NCOVID Open BranchesDocument9 pagesList of NCOVID Open Branchesaa bbPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender Discrimination in Mahesh Dattanis Dance Like A Man and Tara-2018-11!24!12-19Document4 pagesGender Discrimination in Mahesh Dattanis Dance Like A Man and Tara-2018-11!24!12-19Impact Journals100% (1)

- Breaking The Tradition: Joan Didion and The Complexity of GriefDocument7 pagesBreaking The Tradition: Joan Didion and The Complexity of GriefFunshine908Pas encore d'évaluation

- Employment Contracts in India: Enforceability of Restrictive CovenantsDocument34 pagesEmployment Contracts in India: Enforceability of Restrictive CovenantsApoorv SinghalPas encore d'évaluation

- HORMONAL CONTRACEPTION PresentationDocument25 pagesHORMONAL CONTRACEPTION Presentationjaish8904Pas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals, Fifth CircuitDocument12 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fifth CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Handbook On USSR Military Forces - Chapter III Field OrganizationDocument36 pagesHandbook On USSR Military Forces - Chapter III Field Organizationdiablero999Pas encore d'évaluation

- Gabionza v. CADocument3 pagesGabionza v. CAIan Joshua RomasantaPas encore d'évaluation

- ERNESTO SYKI, Petitioner, Vs - SALVADOR BEGASA, Respondent Keyword: Reckless Truck Driver DoctrineDocument2 pagesERNESTO SYKI, Petitioner, Vs - SALVADOR BEGASA, Respondent Keyword: Reckless Truck Driver DoctrineMaria Recheille Banac KinazoPas encore d'évaluation

- Ang Vs CADocument2 pagesAng Vs CAFranco David Barateta100% (2)

- All Quiet On The Western Front Summative AssessmentDocument1 pageAll Quiet On The Western Front Summative Assessmentapi-303000819Pas encore d'évaluation

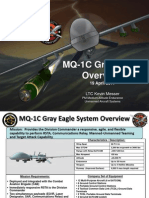

- UAS Scty - Gray Eagle OverviewDocument17 pagesUAS Scty - Gray Eagle Overviewcicogna76100% (1)

- Land Law 2Document6 pagesLand Law 2Richard MutachilaPas encore d'évaluation

- Adoption of Payal at SharineeDocument8 pagesAdoption of Payal at SharineeamanPas encore d'évaluation

- Flores V DrilonDocument2 pagesFlores V Drilonelva depanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Daily Lesson Plan: B. PerformanceDocument4 pagesDaily Lesson Plan: B. PerformanceNikkay Gepanaga CejarPas encore d'évaluation

- A HISTORY OF US GOVERNMENT EXPERIMENTS ON HUMAN SUBJECTS (Men, Women and Children)Document26 pagesA HISTORY OF US GOVERNMENT EXPERIMENTS ON HUMAN SUBJECTS (Men, Women and Children)Impello_TyrannisPas encore d'évaluation

- MOVIE4UDocument10 pagesMOVIE4USGPas encore d'évaluation

- The Threat of PMCsDocument6 pagesThe Threat of PMCsDevon BowersPas encore d'évaluation

- Dissociative DisordersDocument24 pagesDissociative DisordersSimón Ortiz LondoñoPas encore d'évaluation

- ProQuestDocuments 2023 01 14Document14 pagesProQuestDocuments 2023 01 14Daniel KoffmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Office of The Punong BarangayDocument1 pageOffice of The Punong Barangaymichelle100% (1)

- Dry GuillotineDocument355 pagesDry Guillotinemike HillPas encore d'évaluation

- Civil Rights Activism Beyond the 1960sDocument13 pagesCivil Rights Activism Beyond the 1960smongo_beti471Pas encore d'évaluation

- FOCGB3 Rtest VGU 4ADocument2 pagesFOCGB3 Rtest VGU 4AТаїсія НееренкоPas encore d'évaluation

- Court upholds use of "CanonDocument14 pagesCourt upholds use of "CanonJeffrey CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- German WRG Tournament AmendmentsDocument19 pagesGerman WRG Tournament AmendmentsLuchePas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. 201781 - Geronimo, Et - Al., Vs Sps. CalderonDocument3 pagesG.R. No. 201781 - Geronimo, Et - Al., Vs Sps. CalderonFemme ClassicsPas encore d'évaluation

- Supreme Court Rules on Debt Relief Program PowersDocument28 pagesSupreme Court Rules on Debt Relief Program PowersMokeeCodillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Law and Economics ProjectDocument17 pagesLaw and Economics ProjectKuldeep jajra100% (1)