Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Sissons M&S

Transféré par

lct111Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Sissons M&S

Transféré par

lct111Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

5/20/2016

Delivery | Westlaw UK

Woodfall Landlord & Tenant Bulletin

2016

Case Comment

Marks and Spencer Plc v BNP Paribas

Philip Sissons

Subject: Landlord and tenant. Other related subjects: Contracts

Keywords: Apportionment; Break clauses; Business tenancies; Implied terms; Rent;

Repayments

Case: Marks & Spencer Plc v BNP Paribas Securities Services Trust Co (Jersey) Ltd [2015]

UKSC 72; [2015] 3 W.L.R. 1843 (SC)

*W.L.T.B. 1Introduction

In Marks and Spencer Plc v BNP Paribas [2015] 3 W.L.R. 1843, the Supreme Court determined

that a tenant who has paid a full quarterly instalment of rent prior to the valid exercise of a

break clause is not generally entitled to recover any part of that rent when the break takes

effect. In doing so the court affirmed the decision in Ellis v Rowbotham to the effect that rent

made payable in advance cannot be apportioned as to time. Of wider significance, however,

are the observations made by the court, in particular Lord Neuberger, as regards the proper

test to be applied where a party contends that a term should be implied into a contract. In

explaining the earlier reasoning of Lord Hoffman in A-G of Belize v Belize Telecom Ltd [2009] 1

W.L.R. 1988, his Lordship has provided some welcome clarity to the law of implied terms.

The facts of M&S v BNP Paribas

M&S was the tenant pursuant to four commercial leases, each of which contained a break

clause allowing M&S to terminate the lease on 24 January 2012 by giving six months' prior

written notice. It was a pre-condition to a valid exercise of the break that there were no

arrears of rent and that the tenant had paid the landlord, BNP Paribas, a break premium

equivalent to one year's rent. In each case the lease provided that the rent was payable

"yearly and proportionately for any part of the year by equal quarterly instalments in advance"

on the usual quarter days.1

On 7 July 2011, M&S served a break notice to determine the lease on 24 January 2012. On 19

July 2011, the landlord invoiced the tenant for its share of the insurance rent premium under

Sch.5 ("the insurance rent") in respect of the year from 1 July 2011, in the sum of 14,972.85

http://login.westlaw.co.uk/maf/wluk/app/delivery/document

1/8

5/20/2016

Delivery | Westlaw UK

plus VAT, which the tenant duly paid.

*W.L.T.B. 2 Shortly before 25 December 2011, the tenant paid the landlord the rent due on

that date in respect of the quarter from that date up to and including 24 March 2012, the day

before the next quarter day, thereby ensuring the pre-condition attached to the break clause

regarding payment of rent was satisfied. On or about 18 January 2012 the tenant also paid the

sum of 919,800 plus VAT, representing the break premium. As a result of these payments,

the break notice served on 7 July 2011 was effective, and the lease determined on 24 January

2012.

On 3 September 2012, more than eight months after the expiry of the lease, the landlord

served on the tenant a service charge certificate in respect of the services provided in the

calendar year 2011. This showed that the cost of the services had been less than the estimate,

and the landlord credited the tenant with its excess payment.

The principal issue between the parties at trial was whether the tenant was entitled to be

refunded a sum equal to the apportioned basic rent in respect of the period 24 January 2012

(when the lease expired) and 25 March 2012, given that the claimant had paid the basic rent

(in the sum of 309,172.25 plus VAT) on 25 December 2011 in respect of that period even

though the Lease had expired on 24 January 2012.

At first instance, Morgan J held2 that the tenant was entitled to recover the overpayment. The

landlord was obliged to repay an apportioned part of the rent paid on 25 December 2011

pursuant to an implied term. The judge considered that the suggested implied term was both

necessary to give business efficacy to the lease and, with reference to the judgment of Lord

Hoffman in the Belize Telecom case (considered in further detail below) was obviously what

the parties meant as judged from the words used in the lease.

The Court of Appeal allowed the landlords' appeal.3 Lady Justice Arden considered that there

was no basis for implying the term contended for by the tenant. The parties would have been

aware, at the time that they were negotiating the lease, that it was possible that the tenant

would "overpay" in respect of part of a rental quarter falling after the successful operation of

the break clause. If the lease did not make express provision for recovery, then there was no

reason to imply a right to repayment.

The tenant appealed to the Supreme Court contending that there should be implied into the

lease a term that, if the tenant exercises the right to break and the lease consequently

determines on 24 January, the landlords ought to pay back a proportion of the basic rent paid

by the tenant due on the immediately preceding 25 December, being apportioned in respect of

the period 24 January up to and including the ensuing 24 March 2012.

Apportionment of rent on the termination of a lease

http://login.westlaw.co.uk/maf/wluk/app/delivery/document

2/8

5/20/2016

Delivery | Westlaw UK

At first sight it may appear odd that M&S was driven to relying upon an implied term to recoup

its payment. Why, it might reasonably be asked, should a tenant ever be obliged to pay rent in

respect of a period of time after the lease has ended? The answer involves the combination of

somewhat antiquated common law rules as to the apportionment of rent with the construction

of lease provisions regarding reservation of rent and the operation of a break clause.

The starting point is the common law principle that rent cannot be apportioned in respect of

time. This principle probably derives from the traditional concept of rent as a service rendered

by tenant to landlord, as opposed to the modern conception of rent as a payment which the

tenant is bound to pay in return for use of the land; see United Scientific Holdings v Burnley

Borough Council [1978] A.C. 904, Woodfall, para.7.001.

Whatever its origins, the common law principle means that if a lease under which rent was

payable in arrears was forfeited (or came to an end prematurely for some other reason) the

landlord lost the right to recover the rent due on the rent day following that determination.

Therefore, the tenant was not obliged to pay rent for a period during which the lease had

continued. In the case of rent payable in arrears, Parliament remedied this situation through

the Apportionment Act 1870, which provides, by s.2, that all rents and other periodical

payments should be considered as accruing from day to day and are apportionable in respect

of time accordingly.

However, in Ellis v Rowbotham [1900] 1 Q.B. 740, the Court of Appeal held that the 1870 Act

did not apply to rent made payable in advance. It follows that under a standard modern

commercial lease, which usually makes rent payable in advance on the usual quarter days, the

tenant is generally liable to pay the whole of the quarterly rent even if the lease is determined

before the next quarter day, whether by forfeiture or the operation of a break clause; see

Canas Property Co Ltd v KL Television Services Ltd [1970] 2 Q.B. 433, Capital and City

Holdings Ltd v Dean Warburg Ltd (1988) 58 P. & C.R. 346; [2007] B.P.I.R. 1, Woodfall,

para.7.045.1.

It is, however, always a question of construction of the particular lease in question whether

the tenant remains liable to pay the entirety of the rent if the lease is terminated before the

end of the period to which it relates.

In M&S, the tenant was obliged to pay the rent "yearly and proportionately for any part of the

year by equal quarterly instalments in advance". By the time the case reached the Supreme

Court, it was common ground between the parties that if the term of the lease expired

*W.L.T.B. 3 by effluxion of time between quarter days, this wording would only require the

tenant to pay a final instalment of rent apportioned up to the date of expiry. However, at first

instance, Morgan J held that this could not be the result where the break clause was exercised.

As at 25 December 2011, when the quarterly rent fell due, the parties could not be sure that

the lease would end on the break date, due to the need to comply with an additional pre-

http://login.westlaw.co.uk/maf/wluk/app/delivery/document

3/8

5/20/2016

Delivery | Westlaw UK

condition. The tenant did not seek to challenge that aspect of the decision on appeal.

The Supreme Court invited the tenant to argue that Ellis v Rowbotham should be overruled so

that rent payable in advance could also be apportioned as to time. However, in the end, the

court approved the decision in Ellis. Lord Neuberger reasoned that it was a relevant

consideration that the decision had stood for well over 100 years and had been followed and

applied in a number of cases. Even absent of those considerations his lordship regarded the

reasoning of Smith AL and Romer LJJ in Ellis as correct because (i) the mischief that the 1870

Act was concerned to correct related solely to rent in arrears, and (ii) rent paid in advance

could not be said to be "accruing from day to day" unlike rent in arrears.

As a result of these principles, it has long been the understanding of practitioners that where a

pre-condition to the operation of a tenant's break clause requires that there are no arrears of

rent on the break date, it is usually necessary (subject always to the proper construction of the

particular break clause and reservation of rent) to pay the whole of the rent falling due on the

immediately preceding quarter date (see Woodfall, para.17.291). As a result of the affirmation

of Ellis v Rowbotham, the decision in M&S does not alter this position.

Recovery pursuant to an implied term

In M&S there was no dispute that the break had been validly operated. M&S had undoubtedly

ensured that there were no outstanding rent arrears. The question for the court was, instead,

whether M&S could recover the "overpayment" pursuant to an implied term.

In considering this question, the court took the opportunity to re-examine the general

principles underlying the implication of contractual terms and, in particular, to revisit the

observations made by Lord Hoffman in the Privy Council decision, A-G of Belize v Belize

Telecom Ltd [2009] 1 W.L.R. 1988 (see Woodfall, para.11.079).

In the Belize Telecom case, Lord Hoffman noted that the test for an implied term had been

formulated in a variety of different ways. Lord Neuberger in M&S summarised the varying

statements of principle to be found in the authorities as follows:

"There have, of course, been many judicial observations as to the nature of the requirements

which have to be satisfied before a term can be implied into a detailed commercial contract.

They include three classic statements, which have been frequently quoted in law books and

judgments. In The Moorcock (1889) 14 PD 64, 68, Bowen LJ observed that in all the cases

where a term had been implied, "it will be found that the law is raising an implication from

the presumed intention of the parties with the object of giving the transaction such efficacy as

both parties must have intended that at all events it should have'. In Reigate v Union

Manufacturing Co (Ramsbottom) Ltd [1918] 1 KB 592, 605, Scrutton LJ said that " A term can

only be implied if it is necessary in the business sense to give efficacy to the contract'. He

http://login.westlaw.co.uk/maf/wluk/app/delivery/document

4/8

5/20/2016

Delivery | Westlaw UK

added that a term would only be implied if "it is such a term that it can confidently be said that

if at the time the contract was being negotiated' the parties had been asked what would

happen in a certain event, they would both have replied: "Of course, so and so will happen; we

did not trouble to say that; it is too clear.' And in Shirlaw v Southern Foundries (1926) Ltd

[1939] 2 KB 206, 227, MacKinnon LJ observed that, "Prima facie that which in any contract is

left to be implied and need not be expressed is something so obvious that it goes without

saying'. Reflecting what Scrutton LJ had said 20 years earlier, MacKinnon LJ also famously

added that a term would only be implied "if, while the parties were making their bargain, an

officious bystander were to suggest some express provision for it in their agreement, they

would testily suppress him with a common "Oh, of course!""'

In the Belize Telecom case, Lord Hoffman, having noted these various formulations and the

five stage test suggested by Lord Simon of Glaisdale in BP Refinery (Westernport) Pty Ltd v

Shire of Hastings (1977) 180 C.L.R. 266, 282-283, went on to identify an underlying theme in

an attempt to state a general principle.

"The Board considers that this list [from BP v Shire of Hastings] is best regarded, not as series

of independent tests which must each be surmounted, but rather as a collection of different

ways in which judges have tried to express the central idea that the proposed implied term

must spell out what the contract actually means, or in which they have explained why they did

not think that it did so. The Board has already discussed the significance of "necessary to give

business efficacy' and "goes without saying'. As for the other formulations, the fact that the

proposed implied term would be inequitable or unreasonable, or contradict what the parties

have expressly said, or*W.L.T.B. 4 is incapable of clear expression, are all good reasons for

saying that a reasonable man would not have understood that to be what the instrument

meant.

There is only one question: is that what the instrument, read as a whole against the relevant

background, would reasonably be understood to mean"

Thus, Lord Hoffman suggested that the process of implying terms into a contract was part of

the exercise of the construction, or interpretation, of the contract. As Lord Neuberger noted at

para.24 of his judgment in M&S this suggestion was interpreted by both academic lawyers and

judges as having changed the law by diluting the requirements which must be satisfied before

a term will be implied by importing a test of reasonableness as contrasted with necessity or

obviousness.

Lord Neuberger was at pains to stress that this was not the case, stating in terms, that "the

law governing the circumstances in which a term will be implied into a contract remains

unchanged following the Belize Telecom case." His Lordship emphasised that the judgment in

that case ought not to be interpreted as meaning that reasonableness alone is a sufficient

ground for implying a term. Rather:

http://login.westlaw.co.uk/maf/wluk/app/delivery/document

5/8

5/20/2016

Delivery | Westlaw UK

"the notion that a term will be implied if a reasonable reader of the contract, knowing all its

provisions and the surrounding circumstances, would understand it to be implied is quite

acceptable, provided that (i) the reasonable reader is treated as reading the contract at the

time it was made and (ii) he would consider the term to be so obvious as to go without saying

or to be necessary for business efficacy."

Lord Neuberger's second observation on Belize Telecom was addressed to the suggestion that

the implication of terms was an aspect of the process of construction. His Lordship accepted

that in implying a term, the court was seeking to ascertain what the parties had agreed, but

stressed that this involved different considerations from the process of construction as that is

generally understood:

"it is fair to say that the factors to be taken into account on an issue of construction, namely

the words used in the contract, the surrounding circumstances known to both parties at the

time of the contract, commercial common sense, and the reasonable reader or reasonable

parties, are also taken into account on an issue of implication. However, that does not mean

that the exercise of implication should be properly classified as part of the exercise of

interpretation, let alone that it should be carried out at the same time as interpretation. When

one is implying a term or a phrase, one is not construing words, as the words to be implied are

ex hypothesi not there to be construed; and to speak of construing the contract as a whole,

including the implied terms, is not helpful, not least because it begs the question as to what

construction actually means in this context.

Until one has decided what the parties have expressly agreed, it is difficult to see how one

can set about deciding whether a term should be implied and if so what term. This appeal is

just such a case. Further, given that it is a cardinal rule that no term can be implied into a

contract if it contradicts an express term, it would seem logically to follow that, until the

express terms of a contract have been construed, it is, at least normally, not sensibly possible

to decide whether a further term should be implied."

Lords Sumption and Hodge agreed with Lord Neuberger's judgment, which therefore

represents the ratio of the decision. In any case, Lords Carnwath and Clarke also expressed

the view that Belize Telecom did not involve any watering down of the test for an implied term,

albeit that they were less inclined to criticise Lord Hoffman's judgment as potentially creating

confusion.

In terms of the result in the M&S case, their lordships were unanimously of the view that there

was no basis for implying a term obliging the landlord to repay the rent falling due after the

break date. All of the members of the court approved the following reasoning of Lord

Neuberger:

"neither the common law nor statute apportions rent in advance on a time basis. And this

http://login.westlaw.co.uk/maf/wluk/app/delivery/document

6/8

5/20/2016

Delivery | Westlaw UK

was, correctly, generally understood to be the position when the deed and the lease were

negotiated and executed. The [tenant's] argument, by contrast, is that a term should be

implied into the lease that the basic rent payable in advance on 25 December 2011 should

effectively be apportioned on a time basis. The fact that the lease was negotiated against the

background of a clear, general (and correct) understanding that rent payable in advance was

not apportionable in time, raises a real problem for the argument that a term can be implied

into the lease that it should be effectively apportionable if the lease is prematurely determined

in accordance with its terms.

The lease is a very full and carefully considered contract, which includes express obligations of

the same nature as the proposed implied term, namely financial liabilities in connection with

the tenant's right to break, and that term would lie somewhat uneasily with some of those

provisions.

*W.L.T.B. 5

Save in a very clear case indeed, it would be wrong to attribute to a landlord and a tenant,

particularly when they have entered into a full and professionally drafted lease, an intention

that the tenant should receive an apportioned part of the rent payable and paid in advance,

when the non-apportionability of such rent has been so long and clearly established. Given

that it is so clear that the effect of the case law is that rent payable and paid in advance can

be retained by the landlord, save in very exceptional circumstances (e.g. where the contract

could not work or would lead to an absurdity) express words would be needed before it would

be right to imply a term to the contrary."

Conclusion

Whether or not one is persuaded by the suggestion that Belize Telecom did not represent a

departure from the previous authorities, the clarification as to the basis for the implication of a

contractual term is welcome. As the academic criticism of that decision had suggested, Lord

Hoffman's judgment (at least on one interpretation) opened the door to the implication of

terms on a much lower, reasonableness threshold. M&S appears to have closed that door,

reinstating a more orthodox approach.

As for the outcome of the case, again, the reinstatement of the principles established in Ellis v

Rowbotham and subsequent cases brings a welcome certainty. It is now clear both what a

tenant exercising a break clause between quarter days must do to ensure the break is

effective and also what a draftsman must include in future leases in order to ensure a tenant

can recoup any overpayment which it is necessary to make to exercise the break.

Nevertheless, it is difficult not to feel some sympathy for the tenant. Whilst it is of course true

http://login.westlaw.co.uk/maf/wluk/app/delivery/document

7/8

5/20/2016

Delivery | Westlaw UK

to say that the result could easily have been avoided by including an express term in the

lease, it is perhaps unfair to suggest that the principle of no apportionment was so well

established and widely known that it is telling that no such express provision was made.

It remains the case that there is no obvious reason why a landlord should obtain the windfall

of an overpayment in the absence of an express agreement to that effect, particularly where

there was express provision for a break premium. Whilst the reasoning in Ellis may be sound

on its own terms, and there are obviously good policy reasons for not overturning that long-

standing decision, the result of the case and others that will follow appear to be dictated by a

largely historical distinction between rent payable in advance and rent payable in arrears which

does not, it is respectfully suggested, provide a particularly principled basis for a landlord to

retain a significant overpayment.

W.L.T.B. 2016, 1(Feb), 1-5

1.

I.e. 25 March, 24 June, 29 September and 25 December; see Woodfall, para.7.063.

2.

[2013] EWHC 1279.

3.

[2014] EWCA Civ 603.

2016 Sweet & Maxwell and its Contributors

http://login.westlaw.co.uk/maf/wluk/app/delivery/document

8/8

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- El Kanah-The Jealous GodDocument12 pagesEl Kanah-The Jealous GodspeliopoulosPas encore d'évaluation

- Loss or CRDocument4 pagesLoss or CRJRMSU Finance OfficePas encore d'évaluation

- KW Branding Identity GuideDocument44 pagesKW Branding Identity GuidedcsudweeksPas encore d'évaluation

- CH05 Transaction List by Date 2026Document4 pagesCH05 Transaction List by Date 2026kjoel.ngugiPas encore d'évaluation

- SaraikistanDocument31 pagesSaraikistanKhadija MirPas encore d'évaluation

- Position Paper in Purposive CommunicationDocument2 pagesPosition Paper in Purposive CommunicationKhynjoan AlfilerPas encore d'évaluation

- NSF International / Nonfood Compounds Registration ProgramDocument1 pageNSF International / Nonfood Compounds Registration ProgramMichaelPas encore d'évaluation

- Carta de Intencion (Ingles)Document3 pagesCarta de Intencion (Ingles)luz maria100% (1)

- Sample IPCRF Summary of RatingsDocument2 pagesSample IPCRF Summary of RatingsNandy CamionPas encore d'évaluation

- The Micronesia Institute Twenty-Year ReportDocument39 pagesThe Micronesia Institute Twenty-Year ReportherondellePas encore d'évaluation

- Ecm Type 5 - 23G00019Document1 pageEcm Type 5 - 23G00019Jezreel FlotildePas encore d'évaluation

- 2011 CIVITAS Benefit JournalDocument40 pages2011 CIVITAS Benefit JournalCIVITASPas encore d'évaluation

- Narcotrafico: El Gran Desafío de Calderón (Book Review)Document5 pagesNarcotrafico: El Gran Desafío de Calderón (Book Review)James CreechanPas encore d'évaluation

- Human Rights and Its Ratification in India What Are Human Rights?Document5 pagesHuman Rights and Its Ratification in India What Are Human Rights?Aadya PoddarPas encore d'évaluation

- Gun Control and Genocide - Mercyseat - Net-16Document16 pagesGun Control and Genocide - Mercyseat - Net-16Keith Knight100% (2)

- Radio CodesDocument1 pageRadio CodeshelpmeguruPas encore d'évaluation

- Combinepdf PDFDocument487 pagesCombinepdf PDFpiyushPas encore d'évaluation

- United Capital Partners Sources $12MM Approval For High Growth Beverage CustomerDocument2 pagesUnited Capital Partners Sources $12MM Approval For High Growth Beverage CustomerPR.comPas encore d'évaluation

- HSN Table 12 10 22 Advisory NewDocument2 pagesHSN Table 12 10 22 Advisory NewAmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Interconnect 2017 2110: What'S New in Ibm Integration Bus?: Ben Thompson Iib Chief ArchitectDocument30 pagesInterconnect 2017 2110: What'S New in Ibm Integration Bus?: Ben Thompson Iib Chief Architectsansajjan9604Pas encore d'évaluation

- CLP Criminal Procedure - CourtDocument15 pagesCLP Criminal Procedure - CourtVanila PeishanPas encore d'évaluation

- Bookkeeping PresentationDocument20 pagesBookkeeping Presentationrose gabonPas encore d'évaluation

- Labour Cost Accounting (For Students)Document19 pagesLabour Cost Accounting (For Students)Srishabh DeoPas encore d'évaluation

- Filipino ValuesDocument26 pagesFilipino ValuesDan100% (14)

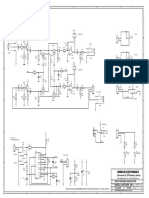

- Nobels Ab1 SwitcherDocument1 pageNobels Ab1 SwitcherJosé FranciscoPas encore d'évaluation

- Bagabuyo v. Comelec, GR 176970Document2 pagesBagabuyo v. Comelec, GR 176970Chester Santos SoniegaPas encore d'évaluation

- "A Stone's Throw" by Elma Mitchell Class NotesDocument6 pages"A Stone's Throw" by Elma Mitchell Class Noteszaijah taylor4APas encore d'évaluation

- Blue Ocean StrategyDocument247 pagesBlue Ocean StrategyFadiPas encore d'évaluation

- Cambodia vs. RwandaDocument2 pagesCambodia vs. RwandaSoksan HingPas encore d'évaluation

- Thomas W. McArthur v. Clark Clifford, Secretary of Defense, 393 U.S. 1002 (1969)Document2 pagesThomas W. McArthur v. Clark Clifford, Secretary of Defense, 393 U.S. 1002 (1969)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation