Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Pervel Industries, Inc. v. T M Wallcovering, Inc., 871 F.2d 7, 2d Cir. (1989)

Transféré par

Scribd Government DocsCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

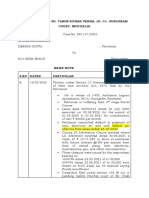

Pervel Industries, Inc. v. T M Wallcovering, Inc., 871 F.2d 7, 2d Cir. (1989)

Transféré par

Scribd Government DocsDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

871 F.

2d 7

PERVEL INDUSTRIES, INC., Petitioner-Appellee,

v.

T M WALLCOVERING, INC., Respondent-Appellant.

No. 61, Docket 88-7100.

United States Court of Appeals,

Second Circuit.

Argued Oct. 18, 1988.

Decided March 22, 1989.

Leo G. Kailas, New York City (Milgrim Thomajan & Lee, P.C. and

Karen I. Hansen, New York City, of counsel), for respondent-appellant.

Donald L. Kreindler, New York City (Kreindler & Relkin, P.C. and Brett

J. Meyer, New York City, of counsel), for petitioner-appellee.

Before VAN GRAAFEILAND, CARDAMONE and PIERCE, Circuit

Judges.

VAN GRAAFEILAND, Circuit Judge:

T M Wallcovering, Inc. appeals from an order of the United States District

Court for the Southern District of New York (Edelstein, J.) staying an action

brought by T M against Pervel Industries, Inc. in Tennessee state court and

directing the parties to proceed to arbitration. See 675 F.Supp. 867. We affirm.

Pervel is a manufacturer of fabrics and wallcoverings. T M is a distributor of

Pervel's products. During the years that the parties dealt with each other,

"numerous orders" were placed by T M with Pervel. In each instance, Pervel

followed its standard practice of returning a printed confirmation form, which

contained the terms of the transaction, including a description of the product

sold, the quantity, the price, the terms of payment, the routing and the

consignee. The document was self-styled a "contract" and provided on its face

that it was subject to the terms therein stated and those on the reverse side

"including the provision for arbitration."

The document also provided on its face that it should become a contract for the

entire quantity specified when signed and returned, or "(b) when Buyer receives

and retains this without objection for ten days or (c) when Buyer accepts

delivery of all or any part of the merchandise ordered hereunder...." Although T

M's president avers that a "large majority" of these confirmation forms were not

signed and returned to Pervel, it is undisputed that some of them were. Seven

such documents, several of which were signed by T M's president, are included

in the record on appeal. We agree with the district court that there was a

binding arbitration agreement between the parties.

Where, as here, a manufacturer has a well established custom of sending

purchase order confirmations containing an arbitration clause, a buyer who has

made numerous purchases over a period of time, receiving in each instance a

standard confirmation form which it either signed and returned or retained

without objection, is bound by the arbitration provision. Genesco, Inc. v. T.

Kakiuchi & Co., 815 F.2d 840, 845-46 (2d Cir.1987); Manes Organization, Inc.

v. Standard Dyeing & Finishing Co., 472 F.Supp. 687, 690-91 n. 4

(S.D.N.Y.1979); In re Arbitration Between Baroque Fashions, Inc. and Scotney

Mills, Inc., 19 A.D.2d 873, 874, 244 N.Y.S.2d 118 (1963) (mem.). This is

particularly true in industries such as fabrics and textiles where the specialized

nature of the product has led to the widespread use of arbitration clauses and

knowledgeable arbitrators. See, e.g., In re Arbitration Between Helen Whiting,

Inc. and Trojan Textile Corp., 307 N.Y. 360, 366-67, 121 N.E.2d 367 (1954); In

re Arbitration Between Gaynor-Stafford Industries, Inc. and Mafco Textured

Fibers, 52 A.D.2d 481, 485, 384 N.Y.S.2d 788 (1976); Imptex Int'l Corp. v.

Lorprint, Inc., 625 F.Supp. 1572 (S.D.N.Y.1986). Thus, the arbitration clause in

the instant case provides that the arbitration shall proceed "in accordance with

the Rules then obtaining of the American Arbitration Association or the

General Arbitration Council of the Textile Industry...." Cf. Trafalgar Square,

Ltd. v. Reeves Brothers, Inc. 35 A.D.2d 194, 196, 315 N.Y.S.2d 239 (1970).

The arbitration clause also provides that it covers any controversy "relating to

this contract." It cannot be contended seriously that the amount of financial

return which T M expected to receive from a contract to purchase Pervel goods

bore no relationship to the purchase contract. See Shaw v. Delta Air Lines, Inc.,

463 U.S. 85, 96-97, 103 S.Ct. 2890, 2899-2900, 77 L.Ed.2d 490 (1983); Peter

Pan Fabrics, Inc. v. Kay Windsor Frocks, Inc., 187 F.Supp. 763, 764

(S.D.N.Y.1959). Neither Pervel nor T M is a philanthropic organization; both

are in business to make money. If, in fact, Pervel gave T M an exclusive

distributorship with a covenant not to compete, it obviously was because both

parties believed it would benefit them financially to do so. It would blink reality

to hold that this desire for profit bore no relationship to the purchase contract.

Indeed, unless and until T M and Pervel entered into a contract for the purchase

and sale of a particular Pervel product, the asserted exclusive distributorship

arrangement for that product did not come into being; the arrangement had no

starting point, no finishing point and no subject matter. It was at best an offer

for a unilateral contract which was accepted, if at all, by T M's purchase from a

particular product line. The relationship between the contract of purchase and

the exclusive distributorship which it created is clear and direct. The district

court therefore correctly distinguished this case from Necchi S.p.A. v. Necchi

Sewing Machine Sales Corp., 348 F.2d 693 (2d Cir.1965), cert. denied, 383

U.S. 909, 86 S.Ct. 892, 15 L.Ed.2d 664 (1966), upon which T M heavily relied.

For all the foregoing reasons, the order of the district court is affirmed.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Petition for Certiorari Denied Without Opinion: Patent Case 98-1972.D'EverandPetition for Certiorari Denied Without Opinion: Patent Case 98-1972.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Merritt Dickstein v. Edmond Dupont, As They Are Partners of Francis I. Dupont & Co., 443 F.2d 783, 1st Cir. (1971)Document7 pagesMerritt Dickstein v. Edmond Dupont, As They Are Partners of Francis I. Dupont & Co., 443 F.2d 783, 1st Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- The Falmouth National Bank v. Ticor Title Insurance Company, 920 F.2d 1058, 1st Cir. (1990)Document10 pagesThe Falmouth National Bank v. Ticor Title Insurance Company, 920 F.2d 1058, 1st Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- 2002 Goss-Reid Associates V Tekniko Licensing Corporation and Landmark EducationDocument6 pages2002 Goss-Reid Associates V Tekniko Licensing Corporation and Landmark EducationFrederick BismarkPas encore d'évaluation

- Cirrus Production Company v. Clajon Gas Company, L.P., A Limited Partnership, 993 F.2d 1551, 10th Cir. (1993)Document9 pagesCirrus Production Company v. Clajon Gas Company, L.P., A Limited Partnership, 993 F.2d 1551, 10th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Nynex Corp. v. Discon, Inc., 525 U.S. 128 (1998)Document8 pagesNynex Corp. v. Discon, Inc., 525 U.S. 128 (1998)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 540, Docket 72-2221Document4 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 540, Docket 72-2221Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Colt Industries Inc. v. Fidelco Pump & Compressor Corporation and Fidelco Equipment Corporation, 844 F.2d 117, 3rd Cir. (1988)Document14 pagesColt Industries Inc. v. Fidelco Pump & Compressor Corporation and Fidelco Equipment Corporation, 844 F.2d 117, 3rd Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Carter-Wallace, Inc. v. Davis-Edwards Pharmacal Corp., 443 F.2d 867, 2d Cir. (1971)Document37 pagesCarter-Wallace, Inc. v. Davis-Edwards Pharmacal Corp., 443 F.2d 867, 2d Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument39 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Diamond Glass Corporation v. Glass Warehouse Workers and Paint Handlers Local Union 206, 682 F.2d 301, 2d Cir. (1982)Document4 pagesDiamond Glass Corporation v. Glass Warehouse Workers and Paint Handlers Local Union 206, 682 F.2d 301, 2d Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals, Second CircuitDocument5 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Second CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument7 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument4 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- T & N PLC v. Fred S. James & Co. of New York, Inc., 29 F.3d 57, 2d Cir. (1994)Document8 pagesT & N PLC v. Fred S. James & Co. of New York, Inc., 29 F.3d 57, 2d Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Alco Capital Resource, Inc. v. Picture It, Inc., A California Corporation, and Rodney Catalano, An Individual, 64 F.3d 669, 10th Cir. (1995)Document9 pagesAlco Capital Resource, Inc. v. Picture It, Inc., A California Corporation, and Rodney Catalano, An Individual, 64 F.3d 669, 10th Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- The Coca-Cola Bottling Company of New York, Inc. v. Soft Drink and Brewery Workers Union, Local 812, International Brotherhood of Teamsters, 39 F.3d 408, 2d Cir. (1994)Document4 pagesThe Coca-Cola Bottling Company of New York, Inc. v. Soft Drink and Brewery Workers Union, Local 812, International Brotherhood of Teamsters, 39 F.3d 408, 2d Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Jack P. Racich and Gertrude C. Racich v. The Celotex Corporation, 887 F.2d 393, 2d Cir. (1989)Document9 pagesJack P. Racich and Gertrude C. Racich v. The Celotex Corporation, 887 F.2d 393, 2d Cir. (1989)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Wembley, Inc. v. Superba Cravats, Inc., 315 F.2d 87, 2d Cir. (1963)Document5 pagesWembley, Inc. v. Superba Cravats, Inc., 315 F.2d 87, 2d Cir. (1963)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- The Serpa v. McWane, Inc., 199 F.3d 6, 1st Cir. (1999)Document12 pagesThe Serpa v. McWane, Inc., 199 F.3d 6, 1st Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Robert L. Zink v. Merrill Lynch Pierce Fenner & Smith, Inc. Peter A. Childs, 13 F.3d 330, 10th Cir. (1993)Document7 pagesRobert L. Zink v. Merrill Lynch Pierce Fenner & Smith, Inc. Peter A. Childs, 13 F.3d 330, 10th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals Third CircuitDocument7 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Third CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Tigg Corporation v. Dow Corning Corporation, 822 F.2d 358, 3rd Cir. (1987)Document10 pagesTigg Corporation v. Dow Corning Corporation, 822 F.2d 358, 3rd Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- John W. Hill v. Texaco, Inc., 825 F.2d 333, 11th Cir. (1987)Document6 pagesJohn W. Hill v. Texaco, Inc., 825 F.2d 333, 11th Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals Third CircuitDocument10 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Third CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument13 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument8 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals, Fifth CircuitDocument12 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fifth CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument14 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals Third CircuitDocument3 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Third CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Gruber v. S-M News Co., Inc, 208 F.2d 401, 2d Cir. (1953)Document4 pagesGruber v. S-M News Co., Inc, 208 F.2d 401, 2d Cir. (1953)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- In The United States Court of Appeals For The Seventh CircuitDocument7 pagesIn The United States Court of Appeals For The Seventh CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Triangle Trading Co. v. Robroy Industries, I, 200 F.3d 1, 1st Cir. (1999)Document7 pagesTriangle Trading Co. v. Robroy Industries, I, 200 F.3d 1, 1st Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Gregory v. Electro-Mechanical Corp., 83 F.3d 382, 11th Cir. (1996)Document7 pagesGregory v. Electro-Mechanical Corp., 83 F.3d 382, 11th Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Island Creek Coal Company v. United Mine Workers of America, District 2, United Mine Workers of America, and Local No. 998, United Mine Workers of America, 507 F.2d 650, 3rd Cir. (1975)Document8 pagesIsland Creek Coal Company v. United Mine Workers of America, District 2, United Mine Workers of America, and Local No. 998, United Mine Workers of America, 507 F.2d 650, 3rd Cir. (1975)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- General Electric Capital v. Union Corp Financial, 4th Cir. (2005)Document9 pagesGeneral Electric Capital v. Union Corp Financial, 4th Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Thermice Corporation v. Vistron Corporation, Standard Oil Chemical Company (Formerly Vistron Corporation), 832 F.2d 248, 3rd Cir. (1987)Document14 pagesThermice Corporation v. Vistron Corporation, Standard Oil Chemical Company (Formerly Vistron Corporation), 832 F.2d 248, 3rd Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument18 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Sidney H. Ingbar, M.D. v. Drexel Burnham Lambert Incorporated, 683 F.2d 603, 1st Cir. (1982)Document10 pagesSidney H. Ingbar, M.D. v. Drexel Burnham Lambert Incorporated, 683 F.2d 603, 1st Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Invengineering, Inc. v. Foregger Company, Inc., and Lily M. Foregger. Invengineering, Inc. v. Foregger Company, Inc., and Lily M. Foregger, 293 F.2d 201, 3rd Cir. (1961)Document6 pagesInvengineering, Inc. v. Foregger Company, Inc., and Lily M. Foregger. Invengineering, Inc. v. Foregger Company, Inc., and Lily M. Foregger, 293 F.2d 201, 3rd Cir. (1961)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- B.L. McTeague & Co., Inc. v. Martin Copeland Company, 753 F.2d 168, 1st Cir. (1985)Document3 pagesB.L. McTeague & Co., Inc. v. Martin Copeland Company, 753 F.2d 168, 1st Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Frank Derwin v. General Dynamics Corporation, 719 F.2d 484, 1st Cir. (1983)Document14 pagesFrank Derwin v. General Dynamics Corporation, 719 F.2d 484, 1st Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument13 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Virginia Carolina Tools, Incorporated American Metal Industries, Incorporated, D/B/A American Metal Industry Wholesalers the Roi Group, Incorporated v. International Tool Supply, Incorporated Curtis Park, 984 F.2d 113, 4th Cir. (1993)Document10 pagesVirginia Carolina Tools, Incorporated American Metal Industries, Incorporated, D/B/A American Metal Industry Wholesalers the Roi Group, Incorporated v. International Tool Supply, Incorporated Curtis Park, 984 F.2d 113, 4th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals, First CircuitDocument11 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, First CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument9 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Richen-Gemco, Inc. v. Heltra, Inc., 540 F.2d 1235, 4th Cir. (1976)Document7 pagesRichen-Gemco, Inc. v. Heltra, Inc., 540 F.2d 1235, 4th Cir. (1976)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Julian Trevathan v. Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company, 944 F.2d 902, 4th Cir. (1991)Document8 pagesJulian Trevathan v. Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company, 944 F.2d 902, 4th Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Tights, Inc. v. The Honorable Edwin M. Stanley, Chief Judge, United States District Court Forthe Middle District of North Carolina, 441 F.2d 336, 4th Cir. (1971)Document13 pagesTights, Inc. v. The Honorable Edwin M. Stanley, Chief Judge, United States District Court Forthe Middle District of North Carolina, 441 F.2d 336, 4th Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Local 103 of The International Union of Electrical, Radio and MacHine Workers, Afl-Cio v. Rca Corporation, 516 F.2d 1336, 3rd Cir. (1975)Document7 pagesLocal 103 of The International Union of Electrical, Radio and MacHine Workers, Afl-Cio v. Rca Corporation, 516 F.2d 1336, 3rd Cir. (1975)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- County Line Investment Company and Wagco Land Development, Inc. v. Calvin L. Tinney, 936 F.2d 582, 10th Cir. (1991)Document5 pagesCounty Line Investment Company and Wagco Land Development, Inc. v. Calvin L. Tinney, 936 F.2d 582, 10th Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- International Union, United Mine Workers of America v. Big Horn Coal Company, A Wyoming Corporation, 916 F.2d 1499, 10th Cir. (1991)Document4 pagesInternational Union, United Mine Workers of America v. Big Horn Coal Company, A Wyoming Corporation, 916 F.2d 1499, 10th Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Budge Manufacturing Co., Inc. v. United States, 280 F.2d 414, 3rd Cir. (1960)Document5 pagesBudge Manufacturing Co., Inc. v. United States, 280 F.2d 414, 3rd Cir. (1960)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument17 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- New Mexico District Council of Carpenters and Joiners of America v. Jordan & Nobles Construction Company, 802 F.2d 1253, 10th Cir. (1986)Document4 pagesNew Mexico District Council of Carpenters and Joiners of America v. Jordan & Nobles Construction Company, 802 F.2d 1253, 10th Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, Local 1228, Afl-Cio v. Wnev-Tv, New England Television Corp., 778 F.2d 46, 1st Cir. (1985)Document6 pagesInternational Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, Local 1228, Afl-Cio v. Wnev-Tv, New England Television Corp., 778 F.2d 46, 1st Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument7 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Sharon Steel Corporation v. Jewell Coal and Coke Company, 735 F.2d 775, 3rd Cir. (1984)Document6 pagesSharon Steel Corporation v. Jewell Coal and Coke Company, 735 F.2d 775, 3rd Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Payn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Document8 pagesPayn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs50% (2)

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Greene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesGreene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Wilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesWilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Brown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Document6 pagesBrown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Webb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document18 pagesWebb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Northglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- CPG vs ACP: Key Differences in Philippine Matrimonial Property RegimesDocument4 pagesCPG vs ACP: Key Differences in Philippine Matrimonial Property RegimesRicardo DelacruzPas encore d'évaluation

- Vda. de Perez vs. ToleteDocument19 pagesVda. de Perez vs. ToleteNullus cumunis0% (1)

- 110-Benguet Consolidated, Inc. v. BCI Employees and Workers' Union-PAFLU G.R. No. L-24711 April 30, 1968Document6 pages110-Benguet Consolidated, Inc. v. BCI Employees and Workers' Union-PAFLU G.R. No. L-24711 April 30, 1968Jopan SJPas encore d'évaluation

- KPTDocument115 pagesKPTUsama AkhtarPas encore d'évaluation

- Brochure y Planímetro en InglésDocument7 pagesBrochure y Planímetro en InglésAndres BejaranoPas encore d'évaluation

- Prescribed InformationDocument3 pagesPrescribed Informationpranav9925694639Pas encore d'évaluation

- Supply Agreement-ConcreteDocument10 pagesSupply Agreement-ConcreteProfessionalPas encore d'évaluation

- Brief Note Baba BanjoDocument5 pagesBrief Note Baba BanjoJai BaijalPas encore d'évaluation

- Tax Remedies and CompromiseDocument5 pagesTax Remedies and Compromiselegine ramaylaPas encore d'évaluation

- Persons SyllabusDocument35 pagesPersons SyllabusAngelo Tiglao100% (1)

- REPORT AND PRESENTATION 9th SemesterDocument40 pagesREPORT AND PRESENTATION 9th SemesterAyushi PriyaPas encore d'évaluation

- What Informal Remedies Are Available To Firms in Financial Distress inDocument1 pageWhat Informal Remedies Are Available To Firms in Financial Distress inAmit PandeyPas encore d'évaluation

- Agreement Contract PM&FDocument3 pagesAgreement Contract PM&FDaniel Song SongPas encore d'évaluation

- Bagonggahasa Vs RomualdezDocument5 pagesBagonggahasa Vs RomualdezShaira Mae CuevillasPas encore d'évaluation

- Guaranty types and extent of surety liabilityDocument26 pagesGuaranty types and extent of surety liabilityerikha_aranetaPas encore d'évaluation

- Template Revenue Sharing Agreement Austria January 2016Document11 pagesTemplate Revenue Sharing Agreement Austria January 2016historymakeover100% (1)

- Ma. Lourdes Florendo vs. Philam PlansDocument2 pagesMa. Lourdes Florendo vs. Philam PlansSheilah Mae Padalla100% (1)

- Special Power of AttorneyDocument2 pagesSpecial Power of Attorneyleah bardoquilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Sales Round2Document63 pagesSales Round2cmv mendoza100% (2)

- Fundamental Accounting Principles Volume 2 Canadian 15th Edition Larson Test Bank Full DownloadDocument39 pagesFundamental Accounting Principles Volume 2 Canadian 15th Edition Larson Test Bank Full Downloadlucasperezcofpywesrb100% (21)

- Civil Liabilities of An AuditorDocument5 pagesCivil Liabilities of An AuditorSyed Sulman SheraziPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter Five - Accounting For CorporationsDocument78 pagesChapter Five - Accounting For CorporationsMelaku WalelgnePas encore d'évaluation

- Draft Service AgreementDocument18 pagesDraft Service AgreementelazaziPas encore d'évaluation

- Taxation 2 Project - UG18-54Document12 pagesTaxation 2 Project - UG18-54ManasiPas encore d'évaluation

- Alpa - Giampieri - Law and Economic and Method Analisis The Contracual DamagesDocument5 pagesAlpa - Giampieri - Law and Economic and Method Analisis The Contracual DamagesfedericosavignyPas encore d'évaluation

- Employment law lecture 3, alternative work relationsDocument8 pagesEmployment law lecture 3, alternative work relationsshivam kPas encore d'évaluation

- Title Ii Legal Separation: ARTICLE 63-67Document23 pagesTitle Ii Legal Separation: ARTICLE 63-67Marj Reña LunaPas encore d'évaluation

- Subsection 1 - Application of PaymentsDocument25 pagesSubsection 1 - Application of PaymentsKang MinheePas encore d'évaluation

- Right of Unpaid Seller: Legal Regulation Commercial TransactionDocument12 pagesRight of Unpaid Seller: Legal Regulation Commercial Transactionamulya anandPas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture - 8 - Current - Liabilities - NUS ACC1002 2020 SpringDocument32 pagesLecture - 8 - Current - Liabilities - NUS ACC1002 2020 SpringZenyuiPas encore d'évaluation

- Permission to Be Gentle: 7 Self-Love Affirmations for the Highly SensitiveD'EverandPermission to Be Gentle: 7 Self-Love Affirmations for the Highly SensitiveÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (13)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionD'EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (402)

- Summary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesD'EverandSummary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1631)

- Breaking the Habit of Being YourselfD'EverandBreaking the Habit of Being YourselfÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (1454)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedD'EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (78)

- Out of the Dark: My Journey Through the Shadows to Find God's JoyD'EverandOut of the Dark: My Journey Through the Shadows to Find God's JoyÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (10)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityD'EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (13)

- The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: The Infographics EditionD'EverandThe 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: The Infographics EditionÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (2475)

- Maktub: An Inspirational Companion to The AlchemistD'EverandMaktub: An Inspirational Companion to The AlchemistÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (2)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeD'EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BePas encore d'évaluation

- The Mountain is You: Transforming Self-Sabotage Into Self-MasteryD'EverandThe Mountain is You: Transforming Self-Sabotage Into Self-MasteryÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (876)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityD'EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsD'EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (3)

- The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentD'EverandThe Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (4120)

- Out of the Dark: My Journey Through the Shadows to Find God's JoyD'EverandOut of the Dark: My Journey Through the Shadows to Find God's JoyÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (5)

- No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems ModelD'EverandNo Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems ModelÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (2)

- The Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismD'EverandThe Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismPas encore d'évaluation

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsD'EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Seven Spiritual Laws of Success: A Practical Guide to the Fulfillment of Your DreamsD'EverandSeven Spiritual Laws of Success: A Practical Guide to the Fulfillment of Your DreamsÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (1547)

- Becoming Supernatural: How Common People Are Doing The UncommonD'EverandBecoming Supernatural: How Common People Are Doing The UncommonÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1477)

- The 5 Second Rule: Transform your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CourageD'EverandThe 5 Second Rule: Transform your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CourageÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (7)

- How to Talk to Anyone: Learn the Secrets of Good Communication and the Little Tricks for Big Success in RelationshipD'EverandHow to Talk to Anyone: Learn the Secrets of Good Communication and the Little Tricks for Big Success in RelationshipÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (1135)