Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

The Finished Article

Transféré par

api-326402750Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The Finished Article

Transféré par

api-326402750Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Gifted and Talented International

ISSN: 1533-2276 (Print) 2470-9565 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ugti20

What contributes to gifted adolescent females

talent development at a high-achieving, secondary

girls school?

Charlotte Tweedale & Leonie Kronborg

To cite this article: Charlotte Tweedale & Leonie Kronborg (2015) What contributes to gifted

adolescent females talent development at a high-achieving, secondary girls school?, Gifted

and Talented International, 30:1-2, 6-18, DOI: 10.1080/15332276.2015.1137450

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15332276.2015.1137450

Published online: 13 Apr 2016.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 24

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ugti20

Download by: [122.56.103.210]

Date: 21 April 2016, At: 12:11

GIFTED AND TALENTED INTERNATIONAL

2015, VOL. 30, NOS. 12, 618

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15332276.2015.1137450

What contributes to gifted adolescent females talent development at a

high-achieving, secondary girls school?

Charlotte Tweedale and Leonie Kronborg

Faculty of Education, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria, Australia

KEYWORDS

Downloaded by [122.56.103.210] at 12:11 21 April 2016

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this research was to examine what contributes to gifted adolescent females talent

development at a high-achieving girls school. Using Kronborgs (2010) Talent Development

Model for Eminent Women as a theoretical framework, this research examined the conditions

that supported and those that hindered the participants talent development in the setting of

their secondary girls school. In this qualitative study, semistructured interviews were conducted

with six gifted females, 1720 years of age, who were all identified as gifted and who achieved

highly in one or more talent domains during their years at their former high-achieving secondary

girls school. The findings of this research support the theoretical framework. The themes found to

support these participants talent development were psychological qualities, individual abilities,

opportunities to achieve in talent domain(s), allies in the family, allies beyond the family,

passionate engagement in talent domain, and feelings and experiences of difference. These

findings add support to the themes Kronborg (2010) found in her Talent Development Model

of Eminent Women.

Introduction

Since feminism began to open the doors for

women to options other than traditional female

roles, researchers have sought to understand why

women are still largely underrepresented in the

top echelons of many professions, despite the

advances made by the feminist movement (Hyde,

2014). Although it must be accepted that there are

clear biological differences between men and

women, feminist researchers contend that many

issues that keep women under the proverbial

glass ceiling are rather gender issues, which they

maintain are societal concepts and can thus be

challenged (Eccles, 2011; Reis, 1995; Rimm,

2001). To understand why women are still a significant minority in many prestigious career

domains, research has been conducted on those

women who have achieved eminence to glean the

conditions that contributed to their success

(Kronborg, 2010; Noble, 1996; Reis, 1995; Rimm,

2001).

gifted adolescent females;

talent development; high

achiever

Although there has been research conducted on

eminent women and their retrospective perceptions

of their childhood and adolescent experiences

(Kronborg, 2008b, 2009, 2010; Noble, 1996; Rimm,

1999), and also gifted adolescent females who

repudiate their giftedness and underachieve (Kerr,

1997; Kerr & McKay, 2014), there has been little

research conducted about adolescent gifted females

who are successful in their talent domains and have

managed to sidestep the pitfalls of adolescence that

research shows stymies gifted girls from actualizing

their gifts and themselves. Much of the research

published about gifted adolescent females was conducted in the 1980s and early 1990s or before. Since

this time, there has been much change in womens

participation in education and in the workplace

(Eccles, 2011). There is also a paucity of research

into gifted females that has been conducted in New

Zealand.

Studies regarding contributing conditions to adult

female eminence have been conducted by Noble,

Subotnik, and Arnold (1999), Rimm (1999), and

Kronborg (2010). There are a number of themes

CONTACT Charlotte Tweedale

ctweedale@cognitioneducation.com

Education Consultant Gifted and Talented Education Facilitator, Cognition

Education, 16 Normanby Road, Mt Eden, Auckland 1024, New Zealand.

Color versions of one or more of the figures in the article can be found online at www.tandfonline.com/ugti.

2015 World Council for Gifted and Talented Children

GIFTED AND TALENTED INTERNATIONAL

that are evident in each of those studies: the salience

of psychological qualities such as resilience and

determination; opportunities to achieve in talent

domain(s); and supportive others, such as family,

teachers, friends, and spouses. Considering all these

conditions that many eminent women report contributed to their success, and the research positing

the challenges that gifted females face in adolescence

that can lead them to eschew their giftedness, it is

therefore of interest to seek to understand whether

the contributors to success reported by eminent

women are also evident in the lives of high-achieving

gifted adolescent females.

Downloaded by [122.56.103.210] at 12:11 21 April 2016

Context of the study

All the adolescent females who participated in

this study had previously attended the same allgirls (single-sex) secondary school. This school is

a state integrated, Anglican girls day and boarding school in an urban New Zealand center catering for girls from years 913. It is the topperforming academic school in its region. In

2011, 96.6% attained a Level 3 National

Certificate of Educational Achievement (New

Zealand Qualifications Authority, 2012) qualification vs. 75.7% nationwide; 57.2% gained a merit

or excellence endorsement vs. 30.5% nationwide

(New Zealand Qualifications Authority, 2012). Of

a cohort of 112 Year 13 students in 2011, four

were offered sports scholarships to U.S. universities, including three Ivy League institutions.

There is a high participation rate in extracurricular activities92% of students are involved in at

least one school-based activity; 87% participate in

team sport, compared to 53% of secondary school

students nationwide. In 2011, the school was the

top New Zealand girls school in rowing and

cycling. Also in 2011, 20 girls represented New

Zealand across 12 sporting codes, and the

schools Sportswoman of the Year went on to

represent New Zealand at the 2012 Olympic

Games. A culture of achievement is evident

throughout the school. Academic, sporting, and

cultural achievements are celebrated in weekly

assemblies; students are proud of their achievements. The 2011 Education Review Office report

stated: Teachers establish strong, supportive and

affirming bonds with students. They are

committed to helping students achieve their

goals, and provide many additional opportunities

for them through coaching, mentoring and tutorials outside of regular class times (Education

Review Office, 2011).

The model

Kronborgs Talent Development Model of

Eminent Women (Fig. 1; Kronborg, 2010) was

based on the exploration of 10 eminent

Australian womens lives, which was framed on

the Model of Adult Female Talent Development

(Noble, 1996; Noble et al., 1999). This model was

chosen as a framework because it incorporated

sociological and psychological perspectives, taking

what seemed a more holistic perspective of talent

development. Furthermore, this model was developed from a synthesis of 23 studies of gifted

females in different contexts. From the model

and the associated studies in Remarkable Women

(Noble et al., 1999), themes that were identified

formed the basis of semistructured interview questions with these women, and feminist research was

used as the methodology. Purposeful sampling was

used to select the eminent women participants

(Patton, 2002). Additionally, these women were

all listed as biographies in the Whos Who in

Australia (De Micheli & Herd, 2004). Eminent

individuals exist within each and every profession.

The definition of eminence used in this study of

Talent Development of Eminent Australian

Women (Kronborg, 2008b) was based on definitions used by Reis (1995) in her study of eminence

in older women, and eminence studies conducted

by Yewchuk and Edmunds (1991). Eminence is

considered to be the highest level of talent development. Eminent individuals are regarded as those

who are capable of high performance or transformational achievements in valued social arenas,

such as a profession or a talent field (Noble

et al., 1999). The eminent women in this study

would be described as gifted in their diverse talent

domains during their school years. Themes found

in this study included allies in family of origin;

psychological qualities; individual abilities; allies

beyond family of origin; feelings and experiences

of difference; schooling opportunities; and selfactualization.

C. TWEEDALE AND L. KRONBORG

FILTERS &

FOUNDATIONS

CATALYSTS

Downloaded by [122.56.103.210] at 12:11 21 April 2016

Demographic

Factors

Motivated by passionate

Socio-economic status.

Religious affiliation,

Nationality & Ethnicity

Geographic location,Marital

status. Number of children,

Loss of parent when young,

Birth Order

engagement in talent

Allies in family of origin

Positive parental support

makes a difference - mother

OR father Influence of

fathers public role, mothers

strength of character &

intelligence, Family culture

with an expectation that girls

could do anything

Psychological qualities Belief in self, Perseverant

effort Resilient behavior,

Independence - striving for

autonomy, Passion,

Courage, Risk-taking

ability, Self determination

Individual Abilities High

ability in talent domain. Creative

problem solving ability. High

general intelligence. High

academic ability

SPHERES OF

INFLUENCE

domains

Allies beyond family of origin

Supportive teachers, friends,

and/or spouse/partner,

Women as role models and

supportive others, Men as

mentors, role models &

supportive others, Distance

mentors & role models in

books. Mentor to other

females

Personal

Domain

SelfActualization

Or Entelechy

Public Domain

Feelings and Experiences

of Difference

Leadership

Luck or chance factors

Taking opportunities to

accomplish or achieve in

Talent Domains -

Eminence

Schooling Opportunities

Arts, Letters/Law Science,

Psycho-social, Business

management, Politics,

Athletics

Figure 1. Kronborgs Talent Development Model of Eminent Women, 2010.

Literature review

Much previous research about high-ability adolescent

females was about those who repudiate their giftedness and underachieve (Kerr, 1997), and it was conducted in the 20th century. There has been significant

change in womens participation in education and the

workplace since then (Eccles, 2011). However, women

are still largely underrepresented in top echelons of

many professions (Hyde, 2014). Understanding shifts

in contributions to talent development of high-ability

adolescent females may shed light on the changes in

this area in future research. In the 2012 World

Economic Forums Global Gender Gap report, New

Zealand ranked 6th (World Economic Forum, 2012).

In countries where women have more schooling

than men, the frontline for change has shifted to

making marriage and motherhood compatible with

fuller economic and political participation of women

(World Economic Forum, 2012). New Zealand has

high female educational achievement. In 2011, 61.9%

females gained a Level 3 NCEA qualification vs. 55.6%

males (NZQA). Between 2005 and 2009, 62% of firstyear university students were female, and they had

lower first-year attrition rates: 23% vs. 30% for males.

Of all first-year engineering students at University of

Auckland, 25% are femalethe highest participation

rate in Australasia (University of Auckland).

However, New Zealand still has a gender gap in

high-status professions. In 2010 data, women comprised the following percentages of roles (National

Equal Opportunities Network, 2010): 18% legal partnerships; 22.5% professors and associate professors;

32% Ministers of Parliament; 9% Fellows of Royal

Society of New Zealand; and 4% NZX top 100

CEOs. At least 30% of companies senior

Downloaded by [122.56.103.210] at 12:11 21 April 2016

GIFTED AND TALENTED INTERNATIONAL

management teams have no female members. New

Zealand, like Australia, is a former British colony that

has developed as a nation with values of egalitarianism, ingenuity, and resilience. We also suffer from

Tall Poppy Syndrome (Moltzen, 2011b). In relation

to gifted education, New Zealanders are wary of giving any group special treatment: We teach our students to strive for adequacy, not excellence (Riley,

2000).

Much of the literature to date posits that although

there are as many gifted females as gifted males,

gifted girls are less able to fulfill their potential without specific interventions (Macleod, 2011). Gifted

girls can experience a self-esteem plunge in adolescence that directly affects their conception of their

giftedness and subsequently leads them to subvert or

camouflage their gifts (Kerr & McKay, 2014). This

self-esteem plunge can affect their academic selfconcept, which in turn influences their academic

success, career choices, and test performance (Klein

& Zehms, 1996). Gifted adolescent females can find

themselves so fearful of failure that they make academic and career choices that are less than commensurate with their abilities (Luscome & Riley, 2001).

As gifted females move from preadolescence to adolescence, their focus can shift from the pursuit of

achievement and self-esteem to the desire for love

and belonging; they prioritize relationships above all

else (Kerr, 2000; Kline & Short, 1991; Lea-Wood &

Clunies-Ross, 1995). Although this is true for adolescent females as a whole, it has been posited that it

is more pernicious in the gifted population due to

gifted females tendency toward perfectionism,

higher levels of self-criticism, and compliance to

gender roles (Luscome & Riley, 2001). Females

silence themselves through adolescence (Schlosser

& Yewchuk, 1998) as they concern themselves with

appropriate female behavior (Reis, 1995). Loss of

female talent has been believed to be a result of

socialization practices (Silverman, 1995), with

females pulling back on their academic and vocational goals in high school and early university years

(Arnold, 1993). This has been attributed to both sex

role threat (Hollinger, 1991; Hollinger & Fleming,

1985; Silverman, 1995) and the anticipation of later

family roles and spousal support (Arnold, 1993;

Eccles, 1987; Grant, Battle, & Heggoy, 2000).

However, there has been a shift in some of the

literature suggesting that the womens movement

has had a positive effect on gifted girls achievements

and aspirations (Roeper, 2003). In her 1993 followup of Project CHOICE, Hollinger found that her

2629-year-old gifted female participants were no

longer seeing career and marriage as an either/or

decision, and they were delaying starting families.

Reis (2002) posited that later marriage leads to

greater self-concept in gifted females. Education

and employment statistics in the OECD tells us the

gender gap is closing (Dai, 2002; Kerr & Foley

Nicpon, 2003). Eccles (2011) also acknowledged the

positive shifts for gifted girls since her studies in the

1980s and 1990s. Most recently, Kerr & McKay

(2014) posited what it means to be a smart girl

today. Although the achievement gaps between

males and females (including in science, technology,

engineering, maths [STEM] fields) are closing, gifted

girls are more overstressed and overworked than

previous generations. Gifted girls aspirations are

higher than ever before, but so is the pressure on

them to achieve. Such onerous expectations can lead

to greater levels of anxiety, sometimes leading to

eating disorders, depression, and other psychopathy

(Kerr & McKay, 2014).

There are some key attributes of gifted adolescent

girls that enable their achievement: They are: smart,

hardworking, independent, active, and interested

(Rimm, 1999). They have an innate desire to win;

they like competition and enjoy being in environments where competition is available and encouraged

(Dai, 2002). When they win, they build confidence;

when they lose, they build resilience (Rimm, 2006).

They have high achievement motivation in their talent

domain(s). This leads to high performance, validating

self-concept (Reis, 2002). Their drive to be the best

causes perseverance (Reis, 1995). They make sacrifices

to achieve their goals. However, they still attribute

failure to lack of ability rather than effort (as opposed

to boys) (Dai, 2002). Perfectionism is present

though this can be a healthy level useful for high

achievement (Perrone, 2007). They have high general

ability/intelligence (Kronborg, 2010; Rimm, 2006)

and high ability in talent domain(s) (Kronborg,

2010). In Kerr & McKays (2014) expansion of

Noble, Subotnik, and Arnolds (1999) Model of

Female Talent Development, she considers how gifted

girls abilities, personalities and values must overlap

for optimal talent development; engagement is also

necessary. Psychological characteristics of gifted

10

C. TWEEDALE AND L. KRONBORG

females who became eminent women include belief in

self, perseverant effort, resilience, independence

striving for autonomy, passion, courage, risk-taking

ability, and self-determination (Kronborg, 2008b,

2010). They also report multipotentialitya sense of

responsibility to use their gifts to the full (Reis, 2002).

Methodology

Downloaded by [122.56.103.210] at 12:11 21 April 2016

Research approach

A qualitative research design was chosen as it

allowed for depth of exploration into participants

perceptions and experiences. Qualitative design is

best for understanding the relation of a context to

the research problem (Creswell, 2007). This

research sits within an interpretivist paradigm.

This approach aims to understand the human

experience and tends to use the perceptions of

the participants being studied and recognizes

how background and experience can affect the

research (Mackenzie & Knipe, 2006). This research

was also approached from a feminist perspective

one that intends to represent gender diversity and

address issues of balance of power (Lichtman,

2010).

Methods of data collection and analysis

A collective case study approach was selected

because this focuses on an issue and uses multiple

cases to illustrate this (Creswell, 2007). Case studies provide rich description of a persons experience to help us gain a multidimensional

understanding of a persons motivations and

experiences. The primary method of data collection was semistructured interviews. These were

based on themes in Kronborgs (2010) Model of

Talent Development for Eminent Women.

Semistructured interviews enable the research to

gain comparable data across subjects (Bogdan &

Biklen, 1998, p. 95). As opposed to other interview

techniques, semistructured interviews provide a

scaffold of questions that remains the same for

each participant, but also allows for individual

divergence from the script (Lichtman, 2010).

Good interviews produce rich data filled with

words that reveal the respondents perspectives

(Bogdan & Biklen, 1998, p. 95). Because the

purpose of this study was to elicit participants

perspectives of their experiences, the semistructured interview was the best choice to acquire

rich data.

Data collection took place over 6 weeks.

Interviews were transcribed during this time

and sent for confirmation as soon as transcription of each was complete. All participants confirmed their transcripts, and at this point, as per

the consent form, all data could no longer be

withdrawn. An abductive research process was

applied to allow for critical and reflective thinking throughout the research process via a reflexive journal and ongoing review of the literature.

The abductive research process is an iterative

one, with periods of immersion in the data

and periods of reflection and analysis (Blaikie,

2009). This allowed for the refining of the

research process while it was happening.

Although the interview protocol did not change,

different emphases were considered for each

interview.

Analysis of each interview began directly after

transcription. Key statements were pulled from

each interview, producing a summary of key statements for each case. All transcript summaries were

then compared, and categorical aggregation was

used to establish themes and subthemes, drawing

meaning across multiple instances of data.

Kronborg (2010) drew meaning and created

themes and subthemes in her Talent

Development Model of Eminent Women, thus

recreated here. All steps were retaken iteratively

over time to ensure replication of themes and

subthemes with each iteration.

Participants

Six adolescent females (Table 1) were purposefully

selected using criterion sampling. Selection criteria

were:

(1) Attended the research site school for at least

3 years;

(2) Identified as academically gifted at the

research site school using the schools 2012

criteria;

(3) Achieved one of the following awards while

attending the research site school as evidence

of accomplishment in talent domain(s):

GIFTED AND TALENTED INTERNATIONAL

11

Table 1. Details of participants (2012).

Name*

(pseudonyms)

Talent Domain(s)

Kelly

Music, Social

Sciences, Visual Arts

Anna

Athletics,

Mathematics, Social

Sciences

Jessica

Mathematics, Social

Sciences, Languages

Rose

Science, Languages

Isabel

Downloaded by [122.56.103.210] at 12:11 21 April 2016

Michelle

Music, Social

Sciences, Languages

Science

Age

Occupation

20 Law and media student

(2nd year)

19 Economics student

(1st year)

Achievements

Top Australian university scholarship; School dux; Arts Laureate

19

Top university scholarship; proxime accessit

20

20

17

Law and business

student (3rd year)

Engineering student

(3rd year)

Law and Languages

student (3rd year)

Pre-medicine, health

sciences student

(1st year)

Dux

Proxime Accessit

Sportswoman of the Year

Arts Laureate

OR achieved a major university scholarship, of

at least NZD$30,000 value

Findings

The findings of this research support the findings

in Kronborgs (2010) study of 10 adult gifted

females across a range of talent domains, which

resulted in the Talent Development Model of

Eminent Women. Most of the themes and subthemes from Kronborgs (2010) study are evidenced in this study. There are some differences,

which may be due to the participants ages and life

stages in this research.

Theme: Individual characteristicspsychological

qualities

High achievement motivation

All participants were highly motivated to achieve

both at school and at university. They are driven

to achieve both their best and be the best. For

these young women, extracurricular participation

was seen as another opportunity to excel. They felt

validated by their achievements, and this made all

their efforts worthwhile. These achievements were

integral to their sense of self: Im aiming to be a

surgeon and Im . . . studying a lot to get the grades

Ivy League Athletics scholarship; School dux; Sportswoman of the Year

Accelerated entry into Engineering; Institute of Professional Engineers

New Zealand and Engineering faculty scholarship scholarships; proxime

accessit

Top university and law firm scholarships; School dux; Arts Laureate

Top university scholarship

I need . . . not let my academics drop . . . I want to

be really successful (Michelle); I like being a high

achiever. I like achieving . . . my goals, so I put the

hard work in. Im very goal oriented (Anna); I

like to do well. I like the success of it (Jessica).

Self-discipline

All participants made a number of sacrifices, often

around social lives and personal time, to achieve

their goals: So Id wake up at 5:30 a.m., study,

then go to school and come home and study until

10:30 p.m. Then the weekends it was just the

whole day studying. I never spent time with

friends (Jessica).

Ability to be alone

All participants reported times when they felt they

had to go it alone to reach their goals. Despite the

high-achieving school environment, these students

perceived that others were not as committed as

them. So even among friends, they reported

being apart from them and their choices: To

have a goal like that was hard because not everyone else had those goals and it can be a bit lonely

up there (Rose).

High self-perceptions and expectations

All participants reported setting high standards for

themselves and being disappointed with themselves

if they were not met. They all perceived themselves

as capable and had expectations of performance

12

C. TWEEDALE AND L. KRONBORG

commensurate to their capabilities. They set their

own standards, not parents or teachers.

When I get an A+ . . . well, thats what I should have

gotI dont see it as a reason to celebrate. And

anything less than what I should have got; I know

that no one else thinks its bad. But Ill still beat

myself up about an average mark. (Isabel)

Downloaded by [122.56.103.210] at 12:11 21 April 2016

I set standards for myself a lot higher than other people

and when I dont meet them I get pretty disappointed.

Because if I dont achieve something, its usually my

own fault. Its not that Im not smart enough, its that I

havent done enough work for it. (Michelle)

Building resilience through failure

These young women were all quick to process

perceived limitations or failure situations and

move on to either improve or learn a lesson for

next time. They reported attributing their perceived failure to lack of effort, not ability. This

contrasts with findings on failure attribution of

gifted females reported previously (Dai, 2002;

Davis, Rimm, & Siegle, 2011; Monaco & Gaier,

1992; Reis, 2002).

In physics, you didnt . . . get excellences every single

time, and in the beginning youd think, Oh my god,

what am I gonna do, Ive failed, but that didnt really

help. I wasnt one for a mental breakdown . . . clearly I

just needed to do more work. And you do more work

. . . I think it was fairly effective to be honest. (Kelly)

Perfectionism

All the young women reported having perfectionistic tendencies to some extent. Mostly, this

pushed them to higher levels of achievement.

Sometimes, though, it led to self-limitations.

If I was willing to try it for the sake of trying it I would

have been ok. But for me it was alwaysyou have to

be really good before you carry on . . . and not have

everyone see youre making mistakes. (Jessica)

Competitiveness

Five of the participants reported being competitive

in the school environmentthey stated this was

common in other high-achieving girls at school.

They posted this competitiveness first as an inherent quality, but also a result of being in a highachieving school: Im just ridiculously competitive in everything . . . probably too competitive at

times (Isabel); Im a competitive person by

nature . . . I know what Im capable of . . . because

I considered myself to have at least equal capacity

to achieve what my peers were achieving, thats

where the competitiveness came in (Anna).

Perseverant effort

These young women pushed themselves to achieve

excellence (A) grades, especially when they had

not achieved a high result at a previous attempt.

This also applied to extracurricular activities.

I kept working, and I got so frustrated because I kept

writing essays and all I wanted was for her (my teacher) to say, yes, this is an excellence (grade) essay,

and my teacher kept saying, youre so close. So I kept

trying and it paid off because in the end Id done

enough work to get excellences in my exams. It made

me keep working, getting those merits. (Michelle)

Theme: Individual characteristicsindividual

abilities

All the participants in this study have high academic

ability and general intelligence, as evidenced in the

criteria for participant selection. They also have high

ability in specific talent domain(s). Additionally,

these participants reported multipotentiality and a

sense of responsibility to use their talents purposefully for good: I know I have a lot of talents which

is kind of scary because when you want to do the

best with what you have and you have a lot youre,

like, what do I do? (Rose); (Its important to me

to) do something worthwhile for the worldmake a

difference . . . to live a life of purpose . . . something I

find to have meaning for me (Anna).

Theme: Opportunities to achieve in talent

domain(s) within a high-achieving, girls school

context

Culture of achievement

All the participants were positive about the school

environment and how their talents were developed. They felt the schools culture of achievement

encouraged and celebrated excellence across a

range of domains. This was coupled with a culture

of girls can do anything: There was definitely a

culture of achievementit was OK to get an excellence and it was kind of revered (Rose).

GIFTED AND TALENTED INTERNATIONAL

Downloaded by [122.56.103.210] at 12:11 21 April 2016

Opportunities for achievement in talent domain(s)

The participants stated that the school provided

many opportunities for extended learning and

achievement. For them, three participated in

school sports, five in the arts, two were prefects,

and two undertook other significant leadership

roles. All participants spoke of ability-grouped

classes in the junior school and the scholars

group in the senior school as being of importance

to their talent development.

Perceived challenges

Limitations of the national assessment system

(NCEA) provided the core challenge reported by

participants. From their analysis of the education

examination system, they were aware that they

might show great depth of knowledge in their

examinations but yet one minor mistake could

lower their grade. They reported that they found

the university grading systems more holistic.

Participants also reported frustration with mixed

ability groupings in their senior high school years.

They dealt with this by self-extension or by working with a small group of like-minded others.

As soon as we moved into NCEA the groups changed . . . and youre in these very diverse classes of

abilities . . . that got annoying at times . . . I didnt

(want) to be with all these disinterested people . . .

Because of the way classes were with a huge range of

ability, teachers would be likeyouve done really

well, but Ive got to concentrate on the people who

arent passing. (Isabel)

Theme: Allies within the family

Positive parental support

These female participants acknowledged their parents provided both personal and financial support.

All the participants perceived that their parents

had made sacrifices to send them to this school,

and they felt responsible for making the most of

their education.

When I used to get up at 5:30 a.m. mum would

get up at 5 a.m. and turn the heater on for me and

make me breakfast . . . that kind of support is really

nice. (Jessica)

My parents have sacrificed quite a lot for my education . . . its hard for them to send us to that school

13

and seeing that has kind of motivated me to do well,

to justify them spending that money on me. (Anna)

Parents as role models

Two participants discussed their mothers as

being role models for them as high-achieving

women. Parents of these participants were highly

educated11 of the 12 were university educated,

and three had PhDs.

Positive parental expectations

Participants reported that parents expected them

to do their best, but they were not unreasonable.

They stated that high expectations were set by

themselves, not their parents, nor were their career

choices stymied by parental expectations: (My

parents) just always expected the best that I can

do, which is not do ten hours of study a night but

just the marks you know youre capable of

(Anna).

Theme: Allies beyond the family

Teachers support and commitment

All the young women in this study felt that their

teachers dedication contributed to their achievements. They posited that teachers were supportive

and cared for them. Participants felt that their

teachers were willing to go above and beyond

their professional expectations to assist achievement (e.g., extra tutorials). They also felt that

teachers offered more opportunities to them as

high-ability students. They reported their teachers

high expectations of them were a positive motivator, and this was connected to their emotional

support. Thus confidence was built through

acknowledging and supporting their differences:

Lots of teachers want to see you achieve and

help you achieve and if you ask for extra help

theyll always give it (Michelle); Mrs. [named

teacher] was really good at supporting how different I was . . . she was always encouraging me and

helped me believe in myself. She did things which

gave me confidence (Rose).

Friends and like-minded peers

All the young women in this study spoke of the

importance of people who got them, though

these were in short supply at school; they found

14

C. TWEEDALE AND L. KRONBORG

more like-minded friends at university. The

schools Scholars group provided them with

allies via group seminars and mentoring from the

teacher-in-charge. Only two of the participants

had boyfriends while at school, and neither

described these relationships as serious. When

asked about future aspirations, four were ambivalent about marriage and children, and one was

definite she did not want either.

Downloaded by [122.56.103.210] at 12:11 21 April 2016

Having other people that were intelligent around

mepeople to talk technical stuff with, do a

science fair project with, hang out on the weekend

and tell intelligent jokes, not just go shopping. We

could do things . . . that were less socially fun but

we enjoyed itit was good to have peers that were

like-minded. (Rose)

I dont know. I might get married, I might have

children . . . I dont really know how I will cross

that bridge if I come to it . . . Id like to have a family

but I dont really know where that fits in. (Isobel)

Theme: Passionate engagement in talent domain

All participants spoke of having a universal love of

learning, motivated by complexity and challenge.

They found it hard to choose subjects because

there were many they were interested in.

I enjoy most subjects for learning . . . cause I

just love learning. (Anna)

With the human body . . . I find it absolutely fascinating how the heart works, and what has to happen

for our muscles to contract . . . I find understanding

how the human body works so interesting. I cant

even explain why because to so many people it

doesnt appeal but to me its so interesting.

(Michelle)

Theme: Feelings and experiences of difference

Being identified as gifted and consequential feelings and experiences of difference were felt to be

mostly beneficial to these young women. They felt

they had more opportunities offered to them; teachers put greater trust in them; and they liked

outward acknowledgment of their achievements.

However, they did not like being singled out by

teachers in the classroom. They felt pressure to

always be gifted and did not want to be so

visible. They also found other girls could be catty

about their achievements, and always expected

them to get high grades. Sometimes they felt

alone in their classesthey did not always fit in

with peers. Despite these feelings and experiences

of difference, these young women liked being who

they were and did not feel pressured to conform to

peers: You get people who are pointedly like, so

that was an excellence was it? Which is fine when

it is, but not so fine when its not (Kelly).

Discussion

Most of the themes of Kronborgs (2008b, 2009,

2010) Talent Development Model of Eminent

Women are evident in this study. Thus conditions

that eminent women report as being salient to

their talent development are also reported in

these young women who exhibit outstanding

talent(s) that contribute to their high achievement

in talent domains. Participants in both studies

share psychological and intellectual characteristics

that drive them to achieve. They all shared environmental and social supports that enabled them to

develop their talents. These findings are distinctive

because much research into gifted girls from the

1990s and earlier suggested that they face barriers

that hinder them from achieving success, yet the

findings of this research suggest that some of those

barriers have been overcome in this schools context. These adolescent women are highly able

(gifted), hard-working, and independent as the

eminent women were in Kronborgs Talent

Development Model of Eminent Women

(Kronborg, 2008b, 2010). These females, at this

stage of their development, in this study, demonstrated high achievement motivation, rather than

relationship motivation; Lovecky (1995) posited

this was a marker of gifted girls who were successful at actualizing their talents.

Friends would say were going to the beach and

dad would say lets go training and Id want to go

to the beach. But . . . I dont regret it now . . . and Im

keeping doing it because I can see what I can get out

of it . . . and its something I can be successful at.

(Anna)

All participants had to make personal sacrifices

to achieve their goals, supporting Kitano and

Perkinss (1996) assertion that talented young

Downloaded by [122.56.103.210] at 12:11 21 April 2016

GIFTED AND TALENTED INTERNATIONAL

women have an indomitable will that allows

them to make difficult choices to achieve their

goals. Participants enjoyed the more competitive

environment of the high-ability grouped classroom, which is supported in the literature positing

talented females enjoy environments where competition is available and encouraged (Dai, 2002).

All participants had high achievement motivation

in all their endeavors and performed highly. This

is consistent with the literature that talented girls

have high achievement motivation (Hollinger &

Fleming, 1984), which drives them to high performance (Reis, 2002).

Previous studies have found that a difference

between gifted girls and boys is that girls are

more likely to attribute failure to a lack of ability

and boys to a lack of effort (Dai, 2002; Reis, 2002).

This failure attribution has been linked to gifted

girls feeling they are not good enough and, subsequently, not developing their gifts (Kerr, 1997).

None of the participants reported that their perceived failure made them feel they were not able.

Rather, they felt they needed to try harder. Perhaps

this is because they engender more traditionally

perceived masculine qualities such as assertiveness

and competitiveness, which enabled them to foster

greater levels of self-belief, and they were encouraged to aim for excellence. They were thus able to

build resilience through perseverant effort

(Kronborg, 2008b, 2010): If I dont achieve something, its usually my own fault. Its not that Im

not smart enough, its that I havent done enough

work for it (Michelle).

Perfectionism seems to have pushed the participants to be perseverant in their efforts to achieve

at high levels. This is consistent with findings that

a healthy level of perfectionism can be useful to

achieve ones personal best (Perrone, 2007; Reis,

2002). The salience of psychological qualities to

participants talent development supported

Kronborgs findings in her model (2010). Both

studies participants held strong self-belief that

enabled

them

to

consistently

achieve.

Independence and resilience to overcome adversity

were evident in both groups of female participants.

Explicit competitiveness and perfectionism were

not factors expressed by the eminent women in

Kronborgs study. This is perhaps due to the age of

this studys participantsadolescent females may

15

feel more of a need to prove themselves, and this

may be related to the need for these students to

achieve high results to attain the goals to which

they aspire. Consistent with the literature, the participants all had high general ability, as reflected in

their high class rankings across a range of subjects

(Kronborg, 2010; Reis, 1995; Rimm, 2006). They

learned quickly and found they outpaced many of

their peers. Five participants discussed issues of

multipotentiality, and four also spoke about the

burden of the sense of responsibility of using

their gifts to better the world. The difficulty of

multipotentiality is also supported by the literature

(Maxwell, 2007; Reis, 2002).

A schools culture of achievement fosters both

high achievement motivation and high achievement (Davis et al., 2011; Monaco & Gaier, 1992).

The context of this all-girl high school provided

these young women with academic challenge and

healthy competition. In the literature, ability

grouping and acceleration is shown to be salient

to talent development (Kronborg, 2010; Kronborg

& Plunkett, 2012; Reis, 2001). All participants were

involved in a range of extracurricular activities,

and all these experiences provided opportunities

for these young women to build greater selfesteem (Hollinger & Fleming, 1985; Kronborg,

2010). Most of Kronborgs (2010) participants discussed opportune schooling experiences as being

of importance to their talent development. They

spoke of opportunities to participate in curricular

and extra-curricular experiences appropriate for

developing their talents (Kronborg, 2010, p. 19).

These included opportunities for extension and

acceleration.

All participants had parents who believed in

girls education. Their parents values were

reflected in their choice of a high-achieving, single-sex school for their daughters education

(Hollinger & Fleming, 1993; Watson, Quatman,

& Edler, 2002). Salience of active parental support

is reflected in the literature (Kronborg, 2010; Reis,

2002; Rimm, 1999). Kronborg (2008a, 2010) found

that parents were the most frequent role models of

the women in her study and that their positive

high expectations of their daughters was significant to their daughters achievements. In

Kronborgs study, all participants reported that

either or both of their parents were highly

Downloaded by [122.56.103.210] at 12:11 21 April 2016

16

C. TWEEDALE AND L. KRONBORG

supportive, believed in their potential and encouraged talent development (Kronborg, 2010, p. 16).

Both the women in Kronborgs study and the

young women in this study were encouraged by

their parents to make the most of their potential

(Kronborg, 2008a). Also, some of the women and

young women in both studies considered their

mothers to be role models, commenting on being

influenced by their mothers intelligence

(Kronborg, 2010, p. 17).

The participants prominent career goals and

ambivalent views on future marriage and children

are a departure from earlier findings and reflect a

significant shift in talented young womens life

expectations (Arnold, 1993; Eccles, 1987; Grant

et al., 2000). All participants reported the salience

of access to like-minded others, which is evident in

literature regarding socialemotional needs of

gifted youth (Davis et al., 2011; Fisher, Stafford,

Maynard-Reid, & Parkinson, 2005). Having the

Scholars program enabled them to feel part of

a valued, inclusive academic group and allowed

them to express themselves freely without concern

for being misunderstood (Fisher et al., 2005).

Many of the teachers who the participants

encountered were highly supportive of their talent

development (Kronborg, 2008b, 2010). Positive

teacher attitudes toward girls achievement are

crucial to gifted girls talent development (Buser,

Stuck, & Casey, 1974; Robinson, 2008). The sense

that teachers are supportive is particularly important to gifted adolescent girls (Davis et al., 2011;

Rimm, 1999). They also appreciated teachers having high expectations of them (Croft, 2003).

Importance of supportive teacher relationships

was found in Kronborgs (2010) study. Eight of

the 10 participants in her study identified certain

teachers as being positively supportive, encouraging, influential or inspirational to the realisation

of their talents (Kronborg, 2010, p. 18). Even in

this high-achieving environment, these young

women reported feelings and experiences of difference. They all spoke of independencealoneness at schooland resilience was evident in their

statements about what it took to achieve their

goals (Kronborg, 2010). The ability to deal with

aloneness and to be independent is posited in the

literature as necessary for gifted women to build

resilience (Noble et al., 1999; Reis, 1995, 2002).

These young women were all passionate in at

least one of their talent domains (Kronborg, 2009).

Kronborg (2009, 2010) found that passionate

engagement in a talent domain was evident in

the women in her study. The adolescent females

in this study were motivated to work hard both by

an intrinsic love of learning as well as the extrinsic

thrill of high achievement. Most participants in

Kronborgs (2009, 2010) study reported feeling a

love or passion for the talent domain that led

them to pursue their talent to high levels. They

were all able to pinpoint a specific time when their

participation in and choice of talent domain crystallized for them and they felt they had found the

direction they wished to take in life (Kronborg,

2009). With the adolescent females in this study,

academic, athletic, and career goals were spoken

about first and with great emphasis when asked

about the future. When reflecting back on their

secondary school experiences, their achievements

were what they most identified with.

Conclusion and limitations

The themes and subthemes found in this study

support Kronborgs (2010) Talent Development

Model of Eminent Women and provide a depth

of understanding when considering gifted adolescent females talent development. Like other case

study research, this research is limited by its lack

of generalizability. Although it provides a picture

of the lived experiences of these participants in a

particular context, the findings cannot be generalized to other settings. The context of this case is

very specific, and this affects the participants

talent development experiences.

The alignment of these findings of this research

with Kronborgs (2010) Talent Development

Model of Eminent Women suggests that the conditions that were present for the talent development process in the eminent women were also

present in these successful gifted adolescent

females lives. Thus we may be able to predict

our eminent women of the future while they are

at secondary school and to take measures to support them in their endeavors. An implication of

this research is that the feminist movement has

gained traction so that gifted adolescent females in

contexts similar to this school are no longer as

GIFTED AND TALENTED INTERNATIONAL

concerned by the culture of romance in adolescence and thus are not confronted by the same

gendered implications to their life choices.

Although it is impossible to generalize with such

a small research sample, such a shift needs to be

considered when counseling gifted adolescent

females about their post-school study and career

choices.

Downloaded by [122.56.103.210] at 12:11 21 April 2016

References

Arnold, K. (1993). Undergraduate aspirations and career outcomes of academically talented women: A discriminant

analysis. Roeper Review, 15, 169175. doi:10.1080/

02783199309553495

Blaikie, N. (2009). Designing social research. Cambridge,

England: Polity.

Bogdan, R., & Biklen, S. K. (1998). Qualitative research for

education (3rd ed.). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Buser, R. A., Stuck, D. L., & Casey, J. P. (1974). Teacher

characteristics and behaviors preferred by high school students. Peabody Journal of Education, 51, 119123.

doi:10.1080/01619567409537953

Creswell, J. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design:

Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks,

CA: Sage.

Croft, L. J. (2003). Teachers of the gifted: Gifted teachers. In

N. Colangelo & G. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of gifted education (3rd ed.; pp.558571). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Dai, D. Y. (2002). Are gifted girls motivationally disadvantaged? Review, reflection and redirection. Journal for the

Education of the Gifted, 25, 315358.

Davis, G. A., Rimm, S. B., & Siegle, D. (2011). Education of

the gifted and talented. Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

De Micheli, C., & Herd, M. (Eds.). (2004). Whos who in Australia

2004 (40th ed.). Melbourne, Australia: Crown Content.

Eccles, J. (1987). Gender roles and womens achievementrelated decisions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 11,

135172. doi:10.1111/pwqu.1987.11.issue-2

Eccles, J. (2011). Understanding womens achievement

choices: Looking back and looking forward. Psychology of

Women

Quarterly,

35,

510516.

doi:10.1177/

0361684311414829

Education Review Office. (2011). (Named School) Education

review. Retrieved from http://ero.govt.nz/index.php/EarlyChildhood-School-Reports/School-Reports/(Named

School)-11-01-2012/

Fisher, T., Stafford, M., Maynard-Reid, N., & Parkerson, A.

(2005). Protective factors for talented and resilient girls.

In S. Kurpius, B. Kerr, & A. Harkins (Eds.), Handbook

for counselling girls and women: Volume 1, talent, risk,

and resiliency (pp. 347378). Mesa, AZ: Nueva Science

Press.

Grant, D., Battle, D., & Heggoy, S. (2000). The journey

through college of seven gifted females: Influences on

17

their career related decisions. Roeper Review, 22, 251260.

doi:10.1080/02783190009554047

Hollinger, C. (1991). Facilitating the career development of

gifted young women. Roeper Review, 13, 135139.

doi:10.1080/02783199109553338

Hollinger, C., & Fleming, E. (1984). Internal barriers to the

realization of potential: Correlates and interrelationships

among gifted and talented female adolescents. Gifted Child

Quarterly, 28, 135139. doi:10.1177/001698628402800308

Hollinger, C., & Fleming, E. (1985). Social orientation and

the social self- esteem of gifted and talented female adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 14, 389399.

doi:10.1007/BF02138834

Hollinger, C., & Fleming, E. (1993). Project Choice: The

emerging roles and careers of gifted women. Roeper

Review, 15(3), 156160.

Hyde, J. S. (2014). Gender similarities and differences.

Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 373398. doi:10.1146/

annurev-psych-010213-115057

Kerr, B. (1997). Smart girls, gifted women. Melbourne,

Australia: Hawker Brownlow Education.

Kerr, B. (2000). Guiding gifted girls and young women. In K.

Heller, F. Monks, R. Sternberg, & R. Subotnik (Eds.),

International handbook of giftedness and talent (2nd ed.,

pp. 649658). Oxford, England: Pergamon.

Kerr, B., & Foley Nicpon, M. (2003). Gender and giftedness.

In N. Colangelo & G. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of gifted

education (3rd ed., pp. 493505). Boston, MA: Allyn &

Bacon.

Kerr, B., & McKay, R. (2014). Smart girls in the 21st century.

Tucson, AZ: Great Potential Press.

Kitano, M., & Perkins, C. (1996). International gifted women:

Developing a critical human resource. Roeper Review, 19,

3440. doi:10.1080/02783199609553781

Klein, A., & Zehms, D. (1996). Self-concept and gifted girls: A

cross sectional study of intellectually gifted females in

grades 3, 5, and 8. Roeper Review, 19, 3034. doi:10.1080/

02783199609553780

Kline, B., & Short, E. (1991). Changes in emotional resilience:

Gifted adolescent females. Roeper Review, 13, 118121.

doi:10.1080/02783199109553333

Kronborg, L. (2008a). Allies in the family contributing to the

development of eminence in women. Australasian Journal

of Gifted Education, 17(2), 514.

Kronborg, L. (2008b). Talent development of eminent

Australian women (Unpublished doctoral dissertation).

Monash University, Clayton, Victoria, Australia.

Kronborg, L. (2009). Passionate engagement in domains contributes to eminent womens talent development.

Australasian Journal in Gifted Education, 18, 1524.

Kronborg, L. (2010). What contributes to talent development

in eminent women? Gifted and Talented International, 25

(2), 1127.

Kronborg, L., & Plunkett, M. (2012). Responding to professional learning: How effective teachers differentiate teaching

and learning strategies to engage highly able adolescents.

Australasian Journal of Gifted Education, 22, 5263.

Downloaded by [122.56.103.210] at 12:11 21 April 2016

18

C. TWEEDALE AND L. KRONBORG

Lea-Wood, S., & Clunies-Ross, G. (1995). Self-esteem of

gifted adolescent girls in Australian schools. Roeper

Review, 17, 195197. doi:10.1080/02783199509553658

Lichtman, M. (2010). Qualitative research in education: A

users guide (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lovecky, D. (1995). Ramifications of giftedness for girls.

Journal of Secondary Gifted Education, 6, 157175.

Luscome, A., & Riley, T. (2001). An examination of selfconcept in academically gifted adolescents: Do gender

differences occur? Roeper Review, 24, 2022. doi:10.1080/

02783190109554120

Mackenzie, N., & Knipe, S. (2006). Research dilemmas:

Paradigms, methods and methodology. Issues in

Educational Research, 16, 193205.

Macleod, R. (2011). Gender issues. In R. Moltzen (Ed.),

Gifted and talented: New Zealand perspectives (3rd ed.,

pp. 340357). Auckland, New Zealand: Pearson.

Maxwell, M. (2007). Career counselling is personal counselling:

A constructivist approach to nurturing the development of

gifted female adolescents. Career Development Quarterly, 55,

206224. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.2007.tb00078.x

Moltzen, R. (2011b). Historical perspectives. In R. Moltzen

(Ed.), Gifted and talented: New Zealand perspectives (3rd

ed., pp. 3153). Auckland, New Zealand: Pearson.

Monaco, N., & Gaier, E. (1992). Single-sex versus coeducational environment and achievement in adolescent

females. Adolescence, 27, 579594.

National Equal Opportunities Network. (2010). New Zealand

Census of Womens Participation 2010. Retrieved from

http://www.neon.org.nz/census2010/womenscensus2010/

New Zealand Qualifications Authority. (2012). Secondary

school statistics NCEA and other NQF qualifications

Participation based Single year of cumulative. Retrieved

from http://www.nzqa.govt.nz/qualifications/ssq/statistics/

provider-selected-crystalreport.do

Noble, K. (1996). Resilience, resistance, and responsibility:

Resolving the dilemma of the gifted woman. In K.

Arnold, K. Noble & R. Subotnik (Eds.), Remarkable

women: Perspectives on female talent development (pp.

413423). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Noble, K., Subotnik, R., & Arnold, K. (1999). To thine own self be

true: A new model of female talent development. Gifted Child

Quarterly, 43, 140149. doi:10.1177/001698629904300302

Patton, M. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Perrone, K. (2007). Perfectionism, achievement and life satisfaction. Advanced Development Journal, 11, 108123.

Reis, S. (1995). Older womens reflections on eminence:

Obstacles and opportunities. Roeper Review, 18, 6672.

doi:10.1080/02783199509553700

Reis, S. (2001). External barriers experienced by gifted and

talented women and girls. Gifted Child Today, 24(4), 2665.

Reis, S. (2002). Internal barriers, personal issues and decisions faced by gifted and talented females. Gifted Child

Today, 25(1), 1428.

Riley, T. (2000, September). Equity with excellence:

Confronting the dilemmas and celebrating the possibilities.

Paper presented at Teaching and Learning: Celebrating

Excellence, Hamilton, New Zealand.

Rimm, S. (1999). See Jane win: The Rimm report on how 1000 girls

became successful women. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press.

Rimm, S. (2001). How Jane won: 55 successful women share

how they grew from ordinary girls to extraordinary women.

New York, NY: Three Rivers Press.

Rimm, S. (2006). Winning girls, winning women. In B.

Wallace & G. Eriksson (Eds.), Diversity in gifted education:

International perspectives on global issues (pp. 189197).

New York, NY: Routledge.

Robinson, A. (2008). Teacher characteristics. In J. A. Plucker

& C. M. Callahan (Eds.), Critical issues and practices in

gifted education (pp. 669680). Waco, TX: Prufrock.

Roeper, A. (2003). The young gifted girl: A contemporary view.

Roeper Review, 25, 151153. doi:10.1080/02783190309554219

Schlosser, G., & Yewchuk, C. (1998). Growing up feeling special:

Retrospective reflections of eminent Canadian women. Roeper

Review, 21, 125132. doi:10.1080/02783199809553943

Silverman, L. (1995). Why are there so few eminent women?

Roeper Review, 18, 513. doi:10.1080/02783199509553689

Watson, C., Quatman, T., & Edler, E. (2002). Career aspirations of adolescent girls: Effects of achievement level, grade

and single-sex school environment. Sex Roles, 46, 323335.

doi:10.1023/A:1020228613796

World Economic Forum. (2012). The Global Gender Gap

Report 2012. Retrieved from http://www3.weforum.org/

docs/WEF_GenderGap_Report_2012.pdf

Yewchuk, C., & Edmunds, A. (1991). Social influences on the

career development of eminent Canadians. In N.

Colangelo, S. Assouline, & D. Ambroson (Eds.), Talent

development proceedings from the national research symposium on talent development (pp. 372375). Melbourne,

Australia: Hawker Brownlow Education.

Author bios

Charlotte Tweedale spent 11 years teaching and leading

learning in New Zealand secondary schools before joining

the GATE consultancy team at Cognition Education in 2015

as a Gifted and Talented Education Facilitator. She was previously the Head of Advanced Learning at an all-girls high

school where she created and imbedded a holistic GATE

program, working to meet gifted and talented students learning and social and emotional needs. Charlotte graduated with

a Masters of Education, specializing in Gifted Education,

from Monash University in 2013.

Dr. Leonie Kronborg is senior lecturer and coordinator of

postgraduate and undergraduate studies in gifted education

in the Faculty of Education, Monash University, Victoria,

Australia. Her research interests and supervision of higher

degree research students have focused on education of gifted

students, teacher education, talent development, gender, and

twice-exceptionality.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Organisational Communication NotesDocument78 pagesOrganisational Communication NotesXakir Mughal50% (2)

- Module 2: Learner-Centered Psychological Principles (LCP) : Polangui Community CollegeDocument8 pagesModule 2: Learner-Centered Psychological Principles (LCP) : Polangui Community CollegeshielaPas encore d'évaluation

- English Lesson Plan 2017Document2 pagesEnglish Lesson Plan 2017FY Chieng100% (3)

- Chapter 1-3Document36 pagesChapter 1-3WENCY DELA GENTEPas encore d'évaluation

- A Beautiful Mind Movie ReviewDocument3 pagesA Beautiful Mind Movie Reviewjosedenniolim100% (1)

- Attitudes Are Evaluative Statements - EitherDocument46 pagesAttitudes Are Evaluative Statements - EitherBalaji0% (1)

- Performance Appraisal and 360 DegreeDocument2 pagesPerformance Appraisal and 360 DegreeHosahalli Narayana Murthy PrasannaPas encore d'évaluation

- People and Organisational Management in Construction (PDFDrive)Document284 pagesPeople and Organisational Management in Construction (PDFDrive)ZzzdddPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gruen Effect: How IKEA's Store Design Makes You Buy MoreDocument2 pagesThe Gruen Effect: How IKEA's Store Design Makes You Buy Moreuday saiPas encore d'évaluation

- Extraverted Intuitive Feeling Perceiving: Enfps Give Life An Extra SqueezeDocument5 pagesExtraverted Intuitive Feeling Perceiving: Enfps Give Life An Extra SqueezeIoana PloconPas encore d'évaluation

- MukkkkkkDocument56 pagesMukkkkkkCindy DengPas encore d'évaluation

- CCB GroupDynamicsGuideDocument10 pagesCCB GroupDynamicsGuideProfesseur TapatiPas encore d'évaluation

- PD 100 Quiz 1 Rachel ElliottDocument2 pagesPD 100 Quiz 1 Rachel Elliottapi-551020543Pas encore d'évaluation

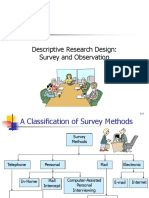

- Descriptive Methods - SurveyDocument23 pagesDescriptive Methods - SurveyPriya GunaPas encore d'évaluation

- Letter From Social Worker On Why We Are Not An Option For Care of Our GrandchildrenDocument5 pagesLetter From Social Worker On Why We Are Not An Option For Care of Our Grandchildrensylvia andrewsPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 4 LeadershipDocument12 pagesChapter 4 LeadershipigoeneezmPas encore d'évaluation

- FMCGDocument2 pagesFMCGKrishnamohan VaddadiPas encore d'évaluation

- Emotional Abuse: What To Look Out For and What To Do If You Think A Child Is Being Emotionally AbusedDocument3 pagesEmotional Abuse: What To Look Out For and What To Do If You Think A Child Is Being Emotionally AbusedPraise Joy DomingoPas encore d'évaluation

- Arenque Educ 3Document23 pagesArenque Educ 3CRING TVPas encore d'évaluation

- CH 9 Foundations of Group BehaviorDocument19 pagesCH 9 Foundations of Group BehaviorKatherine100% (2)

- Effectiveness of Performance Appraisal SDocument26 pagesEffectiveness of Performance Appraisal SmariyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Job Stress QuestionnaireDocument9 pagesJob Stress QuestionnaireAnkita Goel60% (5)

- Commonly Confused Words Affect Vs EffectDocument2 pagesCommonly Confused Words Affect Vs EffectjanepegsPas encore d'évaluation

- DLL Ict G8Document41 pagesDLL Ict G8Neri Barretto De Leon100% (1)

- Enriched Word Game As Supplementary Material For An Enhanced Vocabulary ProficiencyDocument83 pagesEnriched Word Game As Supplementary Material For An Enhanced Vocabulary ProficiencyRoan SonioPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study MGT420Document4 pagesCase Study MGT420herezulfadhli63% (24)

- Difficulties in Solving Mathematical ProblemsDocument21 pagesDifficulties in Solving Mathematical ProblemsJennifer VeronaPas encore d'évaluation

- Article On Being A Multidisciplinary TeamDocument22 pagesArticle On Being A Multidisciplinary TeamLizzie JanitoPas encore d'évaluation

- Sleep Hygiene: Maintain A Regular Sleep ScheduleDocument3 pagesSleep Hygiene: Maintain A Regular Sleep ScheduleGen FelicianoPas encore d'évaluation

- Jamapsychiatry Ashar 2021 Oi 210060 1632764319.53348Document12 pagesJamapsychiatry Ashar 2021 Oi 210060 1632764319.53348FideoPerePas encore d'évaluation