Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Pakistan'S Bomb Mission Unstoppable: Book Reviews

Transféré par

Asad MaqsoodTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Pakistan'S Bomb Mission Unstoppable: Book Reviews

Transféré par

Asad MaqsoodDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

BOOK REVIEWS

PAKISTANS BOMB

Mission Unstoppable

Mark Hibbs # 2008

America and the Islamic Bomb: The Deadly Compromise, by David Armstrong and

Joseph Trento. Steerforth Press, 2007. 292 pages, $24.95.

Deception: Pakistan, the United States, and the Secret Trade in Nuclear Weapons, by

Adrian Levy and Catherine Scott-Clark. Walker & Company, 2007. 586 pages, $28.95.

The Nuclear Jihadist: The True Story of the Man Who Sold the Worlds Most Dangerous

Secrets . . . and How We Could Have Stopped Him, by Douglas Frantz and Catherine

Collins. Twelve, 2007. 413 pages, $25.

KEYWORDS:

Nuclear proliferation; A.Q. Khan; Pakistan; United States; United Kingdom

During the fall of 1994, with preparations under way toward holding a bilateral summit

meeting sometime early in the coming year, I spoke with senior Pakistani officials to learn

whether Benazir Bhutto would heed long-standing U.S. urgings and prevent Pakistans

nuclear program from enriching large amounts of uranium to weapon-grade and then

building atomic bombs.

Bhuttos resurfacing as Pakistans prime minister in late 1993 was seen by some U.S.

officials as an opportunity to move Pakistan in directions Washington favored. The

administration of President Bill Clinton was freshly staffed with personalities who for years

had advocated upgrading the U.S. nonproliferation profile, and the Cold War was rapidly

becoming a memory. It appeared that a window of opportunity might open for Clinton

and Bhutto to effectively address concerns voiced by some U.S. lawmakers and policy

specialists that Pakistan was marching unflinchingly toward possession of nuclear arms.

The biggest open question was whether Bhutto had the freedom of action to rein in

Pakistans nuclear development.

I did not get a clear answer in discussions I had with senior Pakistani officials in 1994.

Bhutto had herself said*in a comment that was expressly not for attribution*that she

was not in charge of making technical decisions about Pakistans uranium enrichment

program and that these matters were left to A.Q. Khan, the Pakistan Atomic Energy

Commission (PAEC), and, ultimately, Pakistans military leaders responsible for the security

of nuclear installations.

On the other hand, I was also informed that Bhutto had made clear to Indian Prime

Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao that unless India agreed to cap its growing stockpile of

weapon-grade plutonium, Pakistan would finish and then operate a plutonium production

reactor, which was secretly under construction at a place called Khushab.

Nonproliferation Review, Vol. 15, No. 2, July 2008

ISSN 1073-6700 print/ISSN 1746-1766 online/08/020381-11

DOI: 10.1080/10736700802117403

382

MARK HIBBS

I had first heard speculation about such a project back in 1989, when executives

running a small German company called NTG were investigated by German justice

authorities for a flurry of hardware sales to India, Pakistan, and South Africa. Engineers

from the firm testified that Pakistan was shopping for piping, valves, and reflector material

for an indigenous 50-megawatt (MW) reactor. At the International Atomic Energy Agency

(IAEA), which monitored Pakistans declared and safeguarded nuclear installations, the

German information about a new project drew a blank.

In October 1994, having obtained direct Pakistani confirmation of the existence of

this reactor, Nucleonics Week, for which I was an editor, published an article identifying the

construction site in northern Pakistan. Within days after the story ran, sources in

Washington began ringing up, explaining that U.S. intelligence had known for years

about Khushab, having gotten wind of the project nearly immediately after it was

spawned in the early 1980s by Munir Khan, the chairman of the PAEC. The Central

Intelligence Agency (CIA) had watched Munir Khan build the reactor. The NTG firm, I was

told on good authority, had never contributed in any significant way to the enterprise. But,

as Pakistani officials had informed me, Western officials believed that China was helping

build the reactor.

By the end of 1994, it was apparent that for about ten years U.S. intelligence

agencies, national laboratory analysts, and three executive branch departments had all

kept their knowledge of the Khushab project secret. That was, I thought then, astonishing.

After all, this development implied that, in addition to A.Q. Khans uranium enrichment

program, which the United States had known about since the late 1970s, there was now a

separate and independent project going on under the noses of the U.S. Embassy and CIA

operatives in Pakistan, which, if continued unabated, would provide Pakistan about 10

kilograms of weapon-grade plutonium every twelve months*maybe enough for a new

nuclear bomb each year.

Old Story, New Facts

One conclusion suggested by the above episode*that U.S. intelligence-handlers for years

protected from public disclosure what they knew about an alarming new development in

Pakistans nuclear program*is consistent with the tableau presented in all three books

considered for this review. A critical subplot is that U.S. intelligence analysts didnt miss a

trick and were fully aware of Pakistans nuclear quest for decades, and that successive U.S.

administrations closeted this sensitive knowledge to prevent outsiders from deterring the

United States from trying to enlist Islamabad to fight successive wars against the Soviet

Union and the Taliban.

All three books relate in straightforward, chronological terms the story of the origins

and development of Pakistans nuclear weapons program over a period of about 40 years.

In America and the Islamic Bomb, David Armstrong and Joseph Trento begin by linking the

birth of Pakistans nuclear ambitions with Dwight D. Eisenhowers Atoms for Peace

program in the late 1950s. Douglas Frantz and Catherine Collins in The Nuclear Jihadist and

Adrian Levy and Catherine Scott-Clark in Deception pick up the trail in 1972, when A.Q.

Khan began working for a laboratory in the Netherlands that had been contracted by the

PAKISTANS BOMB: MISSION UNSTOPPABLE

newly formed trilateral consortium Urenco to assist it in developing gas centrifuges for

uranium enrichment.

From this point on, all three books present accounts that are consistent with

confirmed and well-known facts: Khan steals know-how from Urenco while in the

Netherlands between 1972 and 1975. In 1974 India conducts a nuclear test. In 1976 Khan is

back in Pakistan, where he has impressed its leaders to give him a chance to enrich

uranium to fuel Pakistans own nuclear program. Khan relies on contacts back in Europe to

move his enrichment project forward, and by the end of the 1970s, his role in organizing

the project in Pakistan on the basis of stolen Urenco know-how is exposed in Europe.

Very little of this information is new. The first half of Armstrong and Trentos book*

nearly 150 pages*reiterates, mostly from published sources referred to in copious

footnotes, the chronology of Pakistans nuclear program up to the mid-1990s. Frantz and

Collins chart the same territory in their first twenty chapters. (After Chapter 7, however,

their detailed endnotes abruptly cease; the reader is instead referred to a document on the

books website that supposedly contains the rest of the notes, but which, as of this

writing*more than four months after the books publication*was listed as indefinitely

under construction.) Levy and Scott-Clark likewise devote nearly half of their 600-page

tome to the first twenty years of Pakistans nuclear development.

The accounts become more interesting when they move into territory in which the

authors did real-time reporting. Once onto the backstretch, all three books document in

great detail the record of Pakistans increasingly problematic nuclear diplomacy with the

United States, Washingtons growing dilemma in facing a nuclear-arming Pakistan while

confronting in Afghanistan first the Soviet Union and then the Taliban, the establishment

and then expansion of A.Q. Khans nuclear procurement empire during the 1980s and

1990s, efforts by U.S. and U.K. intelligence to keep track of Khans activities, and, finally, the

fall of A.Q. Khan in the wake of incontrovertible evidence that he had aided nuclear

programs in Libya, Iran, and North Korea.

The books rely on statements and information culled from many sources (the Levy

and Scott-Clark book, its publisher says, was based on hundreds of interviews over a

period of ten years); however, a handful of individuals strongly flavor the message the

books give us.

One is Benazir Bhutto. According to Frantz and Collins, in 1988 Khan conspired with

General Mirza Aslam Beg, the vice chief of the army, to oust her (the publisher says this is one

of the ten new elements of Khans story that distinguish the book from others on the

subject). No details are offered about whether in fact Khan was actively involved in efforts to

overthrow Bhutto, but*in one of many assertions in the last twenty-two chapters that are

neither footnoted nor referenced*the authors say that, Bhutto herself later maintained that

her opposition to going nuclear was one of the reasons she was later ousted from office.

If Khan was involved in Bhuttos ouster, Bhutto did not directly confirm it. In part

based on interviews with her, Levy and Scott-Clark assert that Bhutto opposed Begs

intention to sell Pakistans nuclear wares to other countries and that Beg responded by

simply circumventing Bhutto and dealing with Iran.

Another frequently cited source in two of the books is Peter Griffin, a U.K.

businessman who has had a long, murky relationship with A.Q. Khan. Frantz and Collins

383

384

MARK HIBBS

describe Griffin as someone who could be pugnacious or charming, as the situation

required, and, based on Griffins interactions with reporters since the full extent of Khans

procurement network was publicly exposed in detail beginning in 2004, that description

rings true. Griffin has fiercely combated media allegations that he abetted clandestine

nuclear programs, in two cases suing the BBC and the Guardian newspaper in the United

Kingdom and convincing them to pay damages out of court.

Armstrong and Trento got nowhere with Griffin. They prefaced part of a chapter that

contains allegations about Griffins business dealings*based on U.K. Customs reports*

with a full-page, italicized disclaimer that appears to have been carefully lawyered,

underscoring that the authors made repeated, unsuccessful efforts to get Griffin to talk.

Levy and Scott-Clark fared better. Their tale is laced with plenty of chatty recollections

from Griffin about meetings with Khan and about Griffins run-ins in far-flung locations with

a handful of individuals who since 2003 have been targeted by governments as suspects in

Khans procurement empire. In page after page of these remarks, Griffin seems careful

never to implicate himself in any actions that would constitute a violation of export control

laws or suggest he was party to Khans nuclear schemes.

A U.S. Cover-up?

One witness appearing in all three books is Richard Barlow, a former CIA and Department

of Defense analyst who has sued the U.S. government and has claimed that he was a

victim of a vendetta to ruin his credibility. Since about 2004, Barlow has courted numerous

journalists looking into Pakistans nuclear program, and his testimony in all three books

strongly suggests that the U.S. government ignored intelligence findings and failed to take

action to put a halt to Pakistans nuclear weapons program and destroy Khans network.

That theme is exploited at length by all three accounts.

All three books demonstrate convincingly that, especially during the 1990s and

beyond, stopping Khans network required coordinated international attention. But the

books themselves are strongly focused on how the United States (and for Levy and ScottClark, to a lesser extent, the United Kingdom) responded to the challenge.

The basic conclusion that the United States failed to prevent Pakistan from going

nuclear and A.Q. Khan from exporting his countrys nuclear assets is consistent with the

known facts. But the more attention-grabbing claim that weaves in and out of these

books*that U.S. officials or agencies conspired to mislead the public and prevent action

from being taken to halt the proliferation*has far less meat on the bone.

Levy and Scott-Clark go to considerable pains to convince the reader of the

conspiracy theory, in fact beginning their account with a nine-page overture in which they

summarize their argument: This is the story of how our elected representatives have

conjured a grand deception. . . . The true scandal was how the trade [in nuclear weapons]

and the Pakistan militarys role in it had been discovered by high-ranking US and European

officials, many years before, but rather than interdict it they had worked hard to cover it

up. The cover-up, the authors charge, rapidly bloomed into a complex conspiracy [in

which] evidence was destroyed, criminal files were diverted, Congress was repeatedly lied

to, and . . . presidential appointees even tipped off the Pakistan government so as to

PAKISTANS BOMB: MISSION UNSTOPPABLE

prevent its agents from getting caught in US Customs Service stings that aimed to catch

them buying nuclear components in America.

Armstrong and Trentos account is the most modest of the three with regard to the

claim that U.S. leaders ignored and covered up sinister facts. Their account includes passing

references to successful U.S. diplomacy since the late 1970s to prevent Pakistan from

importing a reprocessing plant from France (the authors even call that development a

dramatic shift in US policy against supporting Atoms for Peace in Pakistan), and they

acknowledge that once Pakistans enrichment program had been exposed, the United

States worked hard to close loopholes in export control commodity lists. (My own historical

files are stuffed with U.S. government diplomatic cables, written between 1978 and the late

1980s, documenting the extent to which U.S. national laboratories, executive branch

agencies, and a dozen U.S. embassies in Asia and Europe pressed foreign governments to

tighten guidelines concerning the export of equipment that could be used for uranium

enrichment.) But Armstrong and Trento on occasion also flirt with the argument that the

U.S. government interfered with the quest for the truth. President Ronald Reagan, they

summarize, for example, had institutionalize[d] the policy of winking at*and in some

cases covering up*Pakistans nuclear program to ensure [Pakistani President Muhammad

Zia ul-Haqs] cooperation [in fighting the Soviet Union in Afghanistan]. As a result,

Islamabads drive for an atomic bomb proceeded virtually unfettered.

But for all three author pairs, the key witness making the claim that virulent forces

were at play in the U.S. failure to crush Khan and Pakistans nuclear program is Barlow. The

books describe Barlows rise from humble origins to become what they imply was the

most committed and best-informed CIA intelligence analyst on the Pakistan nuclear beat.

According to Frantz and Collins, at the zenith of his career, Barlow was a hero within the

CIA. After Barlow in 1987 contradicts a U.S. official during a congressional briefing by

asserting that there were scores of cases where Pakistani agents had tried to illicitly buy

nuclear wares in the United States on behalf of the Pakistani government, Barlows life

takes a dramatic turn for the worse, and he loses his career, his wife, and his government

pension*described in anguishing detail by all the books.

Armstrong and Trento relate that according to Barlow, when he was monitoring

Pakistans nuclear program in the mid-to-late 1980s there was already more than enough

evidence of malfeasance to justify taking action. . . . He believes the Khan networks

subsequent nuclear trafficking was totally and utterly avoidable. We clearly could have

shut it down, Barlow says.

The CIA was up to the minute on this stuff, Barlow remembered, referring to

nuclear smuggling by A.Q. Khans network in Europe during the 1980s, Levy and ScottClark write. We had wiretaps. Phone intercepts. We read mail. The file was as fat as any I

have seen. The difficulty was that no one in the administration . . . gave a damn. And in

Europe the US failed to exert any pressure in case governments pointed to the ambiguity

of US policy regarding Pakistan.

After running into trouble with the CIA and then being hired on as an analyst for the

Department of Defense, Frantz and Collins write, Barlow finally left the government after

having been shaken by the lies told to Congress by the U.S. government: The Pentagon

385

386

MARK HIBBS

bosses who had cooked the intelligence to support the administrations policy then

decided they had to get rid of him. In fact, they decided to destroy him.

Levy and Scott-Clarks book is studded with pages of text in which Barlow asserts

that he was the victim of vicious attacks by administration officials to shipwreck his

personal life and damage his reputation.

Watertight as all three accounts of his life appear in the books, Barlows version of

events is, however, not universally shared. When I asked individuals who for years have

been handling intelligence on Pakistans nuclear program for the U.S. government

whether they could corroborate Barlows assertions, in some cases the answer was no.

One former U.S. official who worked with Barlow told me in March 2008 that it was

certainly true that Barlow was hounded by personal adversaries in the U.S. government.

But, he added, part of the equation was that Barlow had very strong opinions, and if you

didnt agree with him he would treat you as an enemy.

A few people deeply involved in tracking Pakistans nuclear program over the last few

decades confessed to experiencing powerful negative reactions to the Levy and Scott-Clark

account. One said he wanted to throw up after reading claims advanced by Barlow that

U.S. officials conspired to hide the facts and then ruin his life. Barlow presents himself as a

truth-teller, this individual said. Thats not what he was. He ran over a lot of people and has

a lot of axes to grind. The real story is a different story, but its all classified. The problem is

that in books like these, authors have to get close to their sources if they want details, and

the end result wont look tidy and compelling if it contains major contradictions.

Nonproliferation Comes in Second

The subtitle of The Nuclear Jihadist says the book is The true story of the man who sold

the worlds most dangerous secrets . . . and how we could have stopped him. (The main

title is itself misleading; Khan was never a jihadist.) Like the other two sets of authors,

Frantz and Collins suggest that, had the United States and perhaps other governments

taken firm, timely action, Pakistans nuclear weapons program could have been terminated

and Khans smuggling could have been prevented.

Armstrong and Trento seem to imply that the United States gave up the fight to

curb Pakistans nuclear appetite at the outset, citing declassified U.S. government memos

from 1975 showing that the United States was concerned that Pakistan had a solid

incentive to develop nuclear weapons in response to Indias test the year before. Yet

despite all of this the US chose to resume military aid to Pakistan after a ten-year ban, the

authors write.

After investigating and researching Pakistans nuclear program for about twenty

years, it is not clear to me that, on the basis of evidence brought forth in nearly 1,300

pages of these texts, the United States or other governments could have ended it.

There are two known cases in which the United States firmly and directly intervened

during the 1970s to halt clandestine nuclear programs: Taiwan and South Korea. On the

basis of the strong leverage that the United States exercised over both, U.S. officials

walked into laboratories, shut down activities related to plutonium production, and forced

governments to comply with full-scope IAEA safeguards. The United States had no such

PAKISTANS BOMB: MISSION UNSTOPPABLE

leverage with Pakistan. Unlike Pakistan, both Taiwan and South Korea were totally

dependent on the United States for their security vis-a`-vis China and North Korea,

respectively.

All three books profusely document that the United States, seeking to respond to

the Soviet Unions invasion of Afghanistan and then to the rise of the Taliban and Islamic

fundamentalism after the Soviets pulled out, did not single-mindedly pursue the goals of

shutting down Pakistans nuclear weapons program. That is not a revelation. The books

also quote eyewitnesses from the 1980s and 1990s who interpreted this lack of success as

a U.S. policy failure.

One expert who for many years has monitored intelligence for U.S. agencies and

who has read the books told me in February that the policy may have failed to halt

Pakistan from getting nuclear weapons, but it wasnt a cover-up. There was a huge and

intense internal debate. In the end we had to make a choice. When the Soviet Union

invaded Afghanistan, he said, electing to get Pakistan to support the resistance

movement was the obvious choice to make. The nonproliferation concerns would come

in second. The same dilemma arose again when the United States in 2001 considered its

options in combating Islamic terrorism nested in Afghanistan, he said. Priorities had to be

established. Thats what policy making is all about.

I looked in vain in these books for clear insight or guidance about what the United

States, the United Kingdom, and other governments should have done to halt Pakistans

nuclear weapons program. Both Levy and Scott-Clark and Frantz and Collins include an

account of a meeting (it appears to have taken place in 1979) between U.S. officials and

IAEA Director General Sigvard Eklund in which the U.S. officials briefed Eklund in general

terms about Pakistans effort to enrich uranium. Frantz and Collins account states that the

United States would not permit Eklund to discuss U.S. findings with IAEA staffers, and it

seems to imply that the United States failed to cooperate with the IAEA sufficiently to

permit Eklund to intervene with Pakistan. Eklund was in a quandary as a result of what

he was told by the United States, Frantz and Collins write. They quote Eklund as saying,

The only chance of stopping the Pakistanis would be to give wide publicity to the

information, which might lead the responsible countries of the world to put enough

pressure on them to stop the program.

In 2003, the IAEA learned*likewise from member states providing it facts culled

from intelligence data*that Iran had embarked on a hidden uranium enrichment

program. Unlike Pakistan, Iran is a party to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear

Weapons (NPT), and what the IAEA learned constituted violations of Irans commitments in

its safeguards agreement with the IAEA. During the last five years, however, steps taken by

the IAEA and its member states have failed to halt or even suspend Irans enrichment

program.

It thus seems inconceivable that the IAEA or its member states could have halted

Pakistan in 1979. Because Pakistan was not an NPT state, the IAEA had even less leverage

over Pakistan than it did over Iran in 2003, and no mandate to take any independent and

decisive action with Islamabad.

These books briefly mention the policy deliberations of India and Israel*two

countries that, it could be argued, were far more existentially threatened by a nuclear-

387

388

MARK HIBBS

armed Pakistan than was the United States. Both of them, according to the authors, mulled

launching a military strike against nuclear installations in Pakistan. The fact that they did

not, however, might have prompted the authors to pause and reflect whether the United

States itself*with far more on its plate*could have ultimately forced Pakistan to halt its

nuclear weapons program.

The New York Times, Frantz and Collins recalled, revealed in 1979 that the Pentagon

had developed a strategy for an air assault on Kahuta and other nuclear sites in Pakistan if

the diplomatic route failed. The authors said that Israel was also secretly considering air

strikes against the same targets.

One of the most intriguing assertions by Levy and Scott-Clark is the claim that India

and Israel secretly conferred about the possibility of carrying out joint air strikes against

the Kahuta enrichment plant in 1983. According to these authors, Indian Prime Minister

Indira Ghandi had approved the operation, but the CIA somehow scotched the attack by

alerting Pakistani President Zia ul-Haq.

Thereafter, Levy and Scott-Clark recount that in interviews with Pakistani media, A.Q.

Khan had bragged that, Pakistan can set up several nuclear centers of the Kahuta

pattern.

Facing the possibility of foreign military action, however, Khan wasnt bragging.

None of the authors appear to have fully grasped that a military strike against Kahuta

would have set back Pakistans timetable for producing highly enriched uranium for

bombs, but it would not likely have halted the program.

In 1981, Israeli aircraft destroyed a French-supplied reactor in Iraq that could have

generated large amounts of weapon-grade plutonium if finished and operated. In the

wake of IAEA findings after the 1991 Gulf War that Iraq during the 1980s had invested in a

massive uranium enrichment program, some officials investigating that program

concluded that the Israeli attack on the reactor in 1981 had driven Iraqs nuclear program

underground and redoubled Saddam Husseins effort to protect it by opting for an

alternative fissile material production technology*gas centrifuges*which could not

easily be wiped out by foreign aircraft or missiles.

While the reactor site in Iraq was a sitting duck for Israeli aircraft, a gas centrifuge

program would not be. Kahuta was built by replicating hundreds and then thousands of

modular enriching assemblies. Once Khan had learned how to build these, he could keep

producing them and setting them up in any location he chose, including inside facilities

that were bunkered and located underground. One U.S. national laboratory official

involved in recent years in trying to put a halt to North Koreas nuclear program told me in

late 2007 that if we had taken out Kahuta, Pakistan would simply have moved its

centrifuges to a different square on the chessboard.

Unlike a reactor, centrifuges are notoriously difficult to detect. On the basis of what

Khan provided North Korea, U.S. intelligence has been looking for a hidden centrifuge

plant in North Korea for most of this decade. So far, they havent found it.

At the outset of these books, the authors recall that in 1965, nine years before India

tested a nuclear device, Pakistani Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto vowed that if India

went nuclear first, we will eat grass*do whatever was necessary*to obtain nuclear

weapons. That vow was serious. In the face of this kind of determination, do the authors

PAKISTANS BOMB: MISSION UNSTOPPABLE

seriously believe that a cutoff of U.S. aid would have persuaded the Pakistanis to give up

their nuclear weapons ambitions?

What Pakistan accomplished technically was as important to this story as the

accounts in these books of Western governments bureaucratic infighting, personal

vendettas, and massaging of intelligence reports to fit desired policy outcomes, but in all

three books, we learn very little of a technical nature about how A.Q. Khan and Pakistan

succeeded.

A single quote buried in the Frantz and Collins book may get to the heart of the

matter. Charles Van Doren, assistant director of the U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament

Agency during the late 1970s, is cited*the reference is missing*as declaring that

Pakistans nuclear program is a railroad train that is going down the track very fast, and I

am not sure anything will turn it off.

Again and again, the Pakistani Bank of Credit & Commerce International (BCCI) turns

up in all three accounts, and the authors document that Pakistan set up hard-to-penetrate

accounting dodges and shell companies to keep Khan financed and divert U.S. financial

aid to Pakistans nuclear projects. The record is consistent with the behavior of a country

absolutely committed to obtaining nuclear weapons at virtually any cost.

Two of the books bring forth an episode from 2000 that might suggest that U.S. and

U.K. agencies were delinquent in not effectively running down Khans network. In this case,

the United Kingdom abruptly terminated a Customs investigation in Dubai after it began

finding evidence Khan operatives were helping Libya. This, Armstrong and Trento claim,

was a failure of Western intelligence in which the CIAs expressed desire to wait was

merely political cover for U.S. and U.K. policy vis-a`-vis Pakistan that remained

unchanged. But another incident clearly demonstrates that there were solid grounds

why the investigation of Khan waited until 2003 before wrapping up Khans Libyan

project.

In early 2005, I wrote in Nucleonics Week that investigators in Switzerland had seized

documents suggesting that Urs Tinner, an engineer suspected of helping Khan massproduce centrifuge components in a factory set up in Malaysia, was a spy helping the U.S.U.K. investigation of Khan. A few weeks later, a reporter at the New York Times, who had

found my article, called me to let me know that White House officials had denied the story

and had discouraged the Times from pursuing it further.

Frantz and Collins, however, corroborated it. Included on their list of ten new

elements about Khan is the finding that, by early 2000, the CIA had recruited Tinner, and

that he gave the CIA steady reports on the networks most secretive dealings for more

than three years. During that time, Khan was monitored as he provided Libya with plans

for a Chinese-origin nuclear warhead and enough equipment to put Libyas nuclear

weapons project firmly on the road to success.

U.K. and U.S. officials told me in 2007 that a deliberate, top-level government

decision was made not to expose Khans role in Libya and Iran until as much information

as possible about the networks activities had been obtained. Robert Einhorn, former U.S.

assistant secretary for nonproliferation, aptly summarized the situation in Levy and ScottClark, recalling that the State Department was always making the case to roll up the

network now, to stop it doing more damage. The CIA would make a plausible case to keep

389

390

MARK HIBBS

watching, let the network run so eventually we could pick it up by the roots, not just lop

off the tentacles. This does not corroborate Levy and Scott-Clarks thesis that there was a

concerted effort to cover up disturbing facts and prevent action from being taken.

An American from another walk of life, Alan Greenspan, who over many years was

able to move global stock markets by uttering just a few words, said in an interview when

he turned eighty-two early this year that, We are losing influence in the world. The three

books discussed in this review cover a span of four decades during which U.S. prestige

and power has been in decline*in no small part because of contradictions in U.S.

nonproliferation policies and behavior. That dynamic, however, is not reflected in these

books. A few Washington eyewitnesses interviewed seem affected by a time warp and to

have assumed an inflated view of the ability of the United States to project power in a part

of the world where its influence has never been secure and appears to be waning.

None of the books present a clear picture from their sources of what the United

States would have had to do to accomplish its nonproliferation goals in Pakistan without

setting back other foreign policy objectives that at the time were considered paramount.

Pakistan was not Taiwan or South Korea. And compared to India, What was going

on in Pakistan was far less transparent [to U.S. officials] at all levels, one analyst still in the

government told me last year. The assumption of a few people [in Congress] was that if

we cut off aid to Pakistan, we could have stopped them. There was no firm analysis

anywhere backing that up. Could we have slowed their procurement down? Maybe. But

Pakistan was never an ally. They didnt fully depend on us. They always had a Chinese card

up their sleeve, and in their nuclear program they played it.

According to a former U.S. official involved, the United States tried to get both

Germany and France to condition their civilian nuclear trade with China in the early 1980s

on an agreement by China not to assist Pakistans nuclear program. The Europeans, he

said, blew us off. The United States then tried to negotiate directly with China to reach

the same outcome by getting China to abide by international nuclear nonproliferation

norms. After the United States concluded a bilateral nuclear cooperation agreement with

China, it obtained fresh intelligence showing additional disturbing Sino-Pakistani nuclear

commerce. We then refused to implement the U.S.-China agreement. This was hardly

evidence that the U.S. government did not care about the Pakistani nuclear weapons

program, he told me.

An unresolved issue in these books is whether cutting off economic assistance to

Pakistan would have halted Islamabads nuclear weapons activities. The authors fail to

address what consequences this action would have had for the war in Afghanistan, and

they present no case that a cutoff of U.S. assistance would have forced the Pakistanis to

halt their nuclear program and clamp down on Khan.

The three books present a wealth of detail. Some of the material is packaged to

prompt the conclusion that Pakistan succeeded in going nuclear, and Khan in exporting

the products to rogue regimes, because Pakistan took advantage of one unfocused U.S.

administration after another, paralyzed by bureaucratic infighting and engaged in

malevolent backstabbing, disinformation, and even obstruction of justice. The big-picture

truth may be simpler but less diabolical. The Western world had to make uncomfortable

PAKISTANS BOMB: MISSION UNSTOPPABLE

policy choices trading off pressure on Pakistans nuclear program for other goals involving

the Middle East, China, India, and the Soviet Union.

The former U.S. official said that, The fact the U.S. government gave priority to

securing Pakistans assistance in prosecuting the war in Afghanistan did not mean that it

did not care about, or try to stop, the Pakistani nuclear weapons program. The U.S. worked

very hard to halt Khans procurement efforts and made numerous representations to the

Pakistani government stressing that Pakistans pursuit of nuclear weapons threatened U.S.

relations with Pakistan. The United States, he said, set up an interagency committee in the

late 1970s*not in 1986 as the Levy and Scott-Clark book maintains*whose mandate was

to interdict the international procurement efforts of Pakistan. A lot of intelligence and

policy officers worked very hard to stop Pakistani procurement worldwide, although in the

end we were only able to slow down and increase the cost of the program. To suggest

that we just sat by and looked the other way is a distortion of the facts.

Pakistan Plays to Win

Other factors than conspiracy or deceit were at play in decisions taken by U.S. officials to

keep what they knew about Pakistans nuclear program secret.

In 1994, I never anticipated that Pakistani officials would tell me about a clandestine

plutonium production reactor project hitherto subject to vague rumors. But at the time I

never questioned why they did that. Thirteen years later, sources in the United States suggested to me that Pakistan had a good reason for confirming this project to me when it did.

As the Khushab project geared up during the 1980s, U.S. experts handling

intelligence on Pakistan began ringing alarms about it both at the Department of State

and at the White House. But during the four years following the inauguration of President

George H.W. Bush in 1989, officials in the trenches had been unsuccessful in getting Bush

to persuade Pakistan to abandon it. Initial drafts of talking points for the president had

included stopping the plutonium project. But the matter never got to the top of the

agenda and was never raised by Bush during meetings with Pakistani Prime Minister

Mohammad Nawaz Sharif.

In 1993, however, Clinton succeeded Bush, amid some uncertainty in Pakistan about

how the Democrats would handle the nuclear issue. In the fall of 1994 both sides started

preparing for a Bhutto-Clinton summit in Washington. The meeting eventually took place

the following April. U.S. sources said that the decision by Pakistani officials in 1994 to

expose Khushab was taken to handcuff Clinton from persuading Bhutto to agree to halt

the project.

Like their counterparts in Pakistan, for about a decade U.S. officials kept the

existence of this project a secret. The reason, one participant in deliberations told me last

year, was straightforward. So long as Khushab wasnt public, there was a chance the

president could get them to stop it, he said. But as soon as the Pakistanis told you it was

real, we had no card to play. Once it was out in the open, Pakistan would never back

down.

391

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- October 19, 1964 J.S. Mehta, 'China's Bomb and Its Consequences On Her Nuclear and Political Strategy'Document13 pagesOctober 19, 1964 J.S. Mehta, 'China's Bomb and Its Consequences On Her Nuclear and Political Strategy'nanda kumarPas encore d'évaluation

- The Cold Test - Seymour HershDocument5 pagesThe Cold Test - Seymour Hershkhubaib10Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pre Nuclear HistoryDocument22 pagesPre Nuclear HistoryHasnat ManzoorPas encore d'évaluation

- Kissinger Nixon Creation Freedom BangladeshDocument23 pagesKissinger Nixon Creation Freedom BangladeshDani PreetPas encore d'évaluation

- Tsetusuo Wakabayashi RevealedDocument74 pagesTsetusuo Wakabayashi RevealedDwight R RiderPas encore d'évaluation

- The Cuban Missile Crisis in American Memory: Myths versus RealityD'EverandThe Cuban Missile Crisis in American Memory: Myths versus RealityÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5)

- Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro: A Participant's View of the Cuban Missile CrisisDocument9 pagesKennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro: A Participant's View of the Cuban Missile Crisisgeoweb54Pas encore d'évaluation

- Annotatedbibliography MorganbaledgeDocument5 pagesAnnotatedbibliography Morganbaledgeapi-305276478Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pakistan's Nuclear Links with IranDocument6 pagesPakistan's Nuclear Links with IranfaizaPas encore d'évaluation

- Whether To "StrangleDocument46 pagesWhether To "StrangleGuilherme CampbellPas encore d'évaluation

- NHD Competition FinalDocument13 pagesNHD Competition Finalapi-546337950Pas encore d'évaluation

- Abdus Salam: A Reappraisal Salam's Part in The Pakistani Nuclear Weapon ProgrammeDocument6 pagesAbdus Salam: A Reappraisal Salam's Part in The Pakistani Nuclear Weapon ProgrammeTalha AhmadPas encore d'évaluation

- Nuclear Apartheid: The Quest for American Atomic Supremacy from World War II to the PresentD'EverandNuclear Apartheid: The Quest for American Atomic Supremacy from World War II to the PresentPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Paper Over Manhattan ProjectDocument8 pagesResearch Paper Over Manhattan Projectjzczyfvkg100% (1)

- DR Khan and Nuclear NetworkDocument24 pagesDR Khan and Nuclear NetworkfsdfsdfasdfasdsdPas encore d'évaluation

- Actual Work CitedDocument4 pagesActual Work Citedapi-343788621Pas encore d'évaluation

- Nuclear Proliferation International History ProjectDocument73 pagesNuclear Proliferation International History ProjectBurmaa BuramPas encore d'évaluation

- Curtis Peebles - Shadow Flights (2000)Document326 pagesCurtis Peebles - Shadow Flights (2000)Stotza100% (4)

- Piercing the bamboo curtain: Tentative bridge-building to China during the Johnson yearsD'EverandPiercing the bamboo curtain: Tentative bridge-building to China during the Johnson yearsPas encore d'évaluation

- American Conspiracies and Cover-ups: JFK, 9/11, the Fed, Rigged Elections, Suppressed Cancer Cures, and the Greatest Conspiracies of Our TimeD'EverandAmerican Conspiracies and Cover-ups: JFK, 9/11, the Fed, Rigged Elections, Suppressed Cancer Cures, and the Greatest Conspiracies of Our TimeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (3)

- Abdul Qadeer KhanDocument10 pagesAbdul Qadeer KhanKushal MansukhaniPas encore d'évaluation

- War Responsibility of The Chinese Communist Party, The Ussr and CommunismDocument17 pagesWar Responsibility of The Chinese Communist Party, The Ussr and Communismsupernewnew100% (1)

- The U.S Pak RelationsDocument5 pagesThe U.S Pak RelationsMuhammad Usman GhaniPas encore d'évaluation

- 03-17-08 TalkToAction-Navy Friend, Colleague of Admiral SaysDocument5 pages03-17-08 TalkToAction-Navy Friend, Colleague of Admiral SaysMark WelkiePas encore d'évaluation

- Pentagon Papers, The - Volume 5-Critical Essays (Various Authors)Document434 pagesPentagon Papers, The - Volume 5-Critical Essays (Various Authors)Cr0tus100% (2)

- The Manhattan Project: Making The Atomic BombDocument128 pagesThe Manhattan Project: Making The Atomic BombInformation Network for Responsible Mining100% (3)

- Pakistan America RelationshipsDocument6 pagesPakistan America RelationshipsZain UlabideenPas encore d'évaluation

- The Taylor Commission ReportDocument312 pagesThe Taylor Commission ReportPraiseSundoPas encore d'évaluation

- Fallout: The True Story of the CIA's Secret War on Nuclear TraffickingD'EverandFallout: The True Story of the CIA's Secret War on Nuclear TraffickingÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- George F. Kennan and the Making of American Foreign Policy, 1947-1950D'EverandGeorge F. Kennan and the Making of American Foreign Policy, 1947-1950Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Flying Saucers are RealD'EverandThe Flying Saucers are RealÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (17)

- Manhattan Project Thesis IdeasDocument5 pagesManhattan Project Thesis Ideasafktmeiehcakts100% (2)

- Something Extraordinary: A Short History of the Manhattan Project, Hanford, and the B ReactorD'EverandSomething Extraordinary: A Short History of the Manhattan Project, Hanford, and the B ReactorPas encore d'évaluation

- Annotated Bibliography 4 MlaDocument6 pagesAnnotated Bibliography 4 Mlaapi-244911166Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pakistan USA Defense CooperationDocument14 pagesPakistan USA Defense CooperationAmjad AliPas encore d'évaluation

- Annotated Bibliography PeriodDocument2 pagesAnnotated Bibliography Periodapi-307244170Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Other Missiles of October: Eisenhower, Kennedy, and the Jupiters, 1957-1963D'EverandThe Other Missiles of October: Eisenhower, Kennedy, and the Jupiters, 1957-1963Pas encore d'évaluation

- Meltdown: The Inside Story of the North Korean Nuclear CrisisD'EverandMeltdown: The Inside Story of the North Korean Nuclear CrisisPas encore d'évaluation

- IV THE - Clear Press: Question in The IndianDocument38 pagesIV THE - Clear Press: Question in The IndianAstro Vinay KashyapPas encore d'évaluation

- The Coming War With Pakistan: BBC Rewrites 10 Years of History and Declares Pakistan The New EnemyDocument8 pagesThe Coming War With Pakistan: BBC Rewrites 10 Years of History and Declares Pakistan The New EnemyscparcoPas encore d'évaluation

- Ships in The NightDocument43 pagesShips in The Nightboston_nyPas encore d'évaluation

- American Nuclear Deception: Why "the Port Chicago experiment" must be investigatedD'EverandAmerican Nuclear Deception: Why "the Port Chicago experiment" must be investigatedPas encore d'évaluation

- The Atomic Bomb and The End of World War IIDocument48 pagesThe Atomic Bomb and The End of World War IIMarian HarapceaPas encore d'évaluation

- C CC CCCCC CCCC: C C C CDocument9 pagesC CC CCCCC CCCC: C C C CSelena ZhangPas encore d'évaluation

- America's Response to China: A History of Sino-American RelationsD'EverandAmerica's Response to China: A History of Sino-American RelationsÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- The Seventh Decade: The New Shape of Nuclear DangerD'EverandThe Seventh Decade: The New Shape of Nuclear DangerÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1)

- Made in Hanford: The Bomb that Changed the WorldD'EverandMade in Hanford: The Bomb that Changed the WorldÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Annotated Bibliography Colea Kennyv EdsonlDocument5 pagesAnnotated Bibliography Colea Kennyv Edsonlapi-394865540Pas encore d'évaluation

- The United States and China Into The Twenty First Century 4Th Edition Full ChapterDocument40 pagesThe United States and China Into The Twenty First Century 4Th Edition Full Chapterdorothy.todd224100% (25)

- 2008 National Review - Bush Derangement SyndromeDocument7 pages2008 National Review - Bush Derangement SyndromeJeff SturgeonPas encore d'évaluation

- Dr. Abdul Qadeer Khan's Contributions and DownfallDocument5 pagesDr. Abdul Qadeer Khan's Contributions and DownfallQudsiya KalhoroPas encore d'évaluation

- Kissinger Israel Memo-6Document2 pagesKissinger Israel Memo-6Keith KnightPas encore d'évaluation

- Pak-US Relations A Historical Review, Munawar Hussain Footnotes CorrectedDocument16 pagesPak-US Relations A Historical Review, Munawar Hussain Footnotes Correctedmusawar420Pas encore d'évaluation

- Cold War TalesDocument421 pagesCold War TalesConcha FloresPas encore d'évaluation

- Pak. Studies REPORT: Dr. Abdul Qadeer KhanDocument9 pagesPak. Studies REPORT: Dr. Abdul Qadeer KhanAsad Masood QaziPas encore d'évaluation

- U.S. Military Wanted To Provoke War With CubaDocument3 pagesU.S. Military Wanted To Provoke War With CubaNeditha TolentinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Eating Grass: The Making of the Pakistani BombD'EverandEating Grass: The Making of the Pakistani BombÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (4)

- C CC CCCCC CCCC: C C C CDocument9 pagesC CC CCCCC CCCC: C C C CSelena ZhangPas encore d'évaluation

- Analysis of Reduced Forming Steps for an Axisymmetric Deep Drawn PartDocument18 pagesAnalysis of Reduced Forming Steps for an Axisymmetric Deep Drawn PartAsad MaqsoodPas encore d'évaluation

- A Simple Way For Estimating Mechanical Properties From Stress-Strain Diagram Using MATLABDocument5 pagesA Simple Way For Estimating Mechanical Properties From Stress-Strain Diagram Using MATLABAsad MaqsoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Polymer Processing ExperimentDocument2 pagesPolymer Processing ExperimentAsad MaqsoodPas encore d'évaluation

- A Simple Way For Estimating Mechanical Properties From Stress-Strain Diagram Using MATLABDocument5 pagesA Simple Way For Estimating Mechanical Properties From Stress-Strain Diagram Using MATLABAsad MaqsoodPas encore d'évaluation

- A Unified Creep-Fatigue Equation With Application To Engineering Design PDFDocument25 pagesA Unified Creep-Fatigue Equation With Application To Engineering Design PDFAsad MaqsoodPas encore d'évaluation

- 1984 Surf Roughness PGDocument8 pages1984 Surf Roughness PGHussn YazdanPas encore d'évaluation

- Fatigue of StructuresDocument51 pagesFatigue of StructuresJ Guerhard GuerhardPas encore d'évaluation

- Pla Research GateDocument9 pagesPla Research GateAsad MaqsoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Partition of Plastic Work Into Heat and Stored PDFDocument11 pagesPartition of Plastic Work Into Heat and Stored PDFAsad MaqsoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Influence of Layer Thickness, and Rater Angle in 3D Printing PDFDocument16 pagesInfluence of Layer Thickness, and Rater Angle in 3D Printing PDFAsad MaqsoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Influence of Manufacturing Parameters For FDM PLA PDFDocument21 pagesInfluence of Manufacturing Parameters For FDM PLA PDFAsad MaqsoodPas encore d'évaluation

- 1-Very Importantyang - Et - Al - Energy - Dissipation PDFDocument53 pages1-Very Importantyang - Et - Al - Energy - Dissipation PDFAsad MaqsoodPas encore d'évaluation

- A Unified Creep-Fatigue Equation With Application To Engineering Design PDFDocument25 pagesA Unified Creep-Fatigue Equation With Application To Engineering Design PDFAsad MaqsoodPas encore d'évaluation

- PLA and ABS Mechanical Property ComparisonDocument3 pagesPLA and ABS Mechanical Property ComparisonAsad MaqsoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Polymer Processing ExperimentDocument2 pagesPolymer Processing ExperimentAsad MaqsoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Fatigue of StructuresDocument51 pagesFatigue of StructuresJ Guerhard GuerhardPas encore d'évaluation

- Solid Mechanics: Theory, Modeling, and Problems: January 2015Document332 pagesSolid Mechanics: Theory, Modeling, and Problems: January 2015Asad MaqsoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Cumulative Fatigue Damage and Life Prediction TheoriesDocument19 pagesCumulative Fatigue Damage and Life Prediction TheoriesAsad MaqsoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Detailed Evaluation of Methods For Estimation of Cyclic Fatigue With Tensile Data Scince Direct PDFDocument9 pagesDetailed Evaluation of Methods For Estimation of Cyclic Fatigue With Tensile Data Scince Direct PDFAsad MaqsoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Partition of Plastic Work Into Heat and Stored PDFDocument11 pagesPartition of Plastic Work Into Heat and Stored PDFAsad MaqsoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Cumulative Fatigue Damage and Life Prediction Theories A Survey of The State of The Art For Homogeneous MaterialsDocument26 pagesCumulative Fatigue Damage and Life Prediction Theories A Survey of The State of The Art For Homogeneous MaterialsBilu VarghesePas encore d'évaluation

- Parametric Study and Multi-Objective Optimization in Single-Point Incremental Forming of Extra Deep Drawing Steel SheetsDocument13 pagesParametric Study and Multi-Objective Optimization in Single-Point Incremental Forming of Extra Deep Drawing Steel SheetsAsad MaqsoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Influence of Manufacturing Parameters For FDM PLADocument9 pagesInfluence of Manufacturing Parameters For FDM PLAAsad MaqsoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Methods of Extrapolating Low Cycle Fatigue Data To High Stress Am PDFDocument134 pagesMethods of Extrapolating Low Cycle Fatigue Data To High Stress Am PDFAsad MaqsoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Influence of Manufacturing Parameters For FDM PLA PDFDocument21 pagesInfluence of Manufacturing Parameters For FDM PLA PDFAsad MaqsoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Detailed Evaluation of Methods For Estimation of Cyclic Fatigue With Tensile Data Scince DirectDocument30 pagesDetailed Evaluation of Methods For Estimation of Cyclic Fatigue With Tensile Data Scince DirectAsad MaqsoodPas encore d'évaluation

- 02-Sheet Metal Forming ProcessDocument207 pages02-Sheet Metal Forming ProcessAsad MaqsoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Nyquist and Bode Criteria PDFDocument13 pagesNyquist and Bode Criteria PDFAsad MaqsoodPas encore d'évaluation

- l03 Simulation Sheetmetalforming 1 PDFDocument68 pagesl03 Simulation Sheetmetalforming 1 PDFNhan LePas encore d'évaluation

- Zulfikar Ali BhuttoDocument105 pagesZulfikar Ali BhuttoSK Md Kamrul HassanPas encore d'évaluation

- DR ABDUL QADEER KHANDocument4 pagesDR ABDUL QADEER KHANHameer ChandPas encore d'évaluation

- Pakistan's Nuclear Bomb - A Story of Defiance, Deterrance and Deviance (PDFDrive)Document352 pagesPakistan's Nuclear Bomb - A Story of Defiance, Deterrance and Deviance (PDFDrive)Khalil MalikPas encore d'évaluation

- Report On Nuclear EnergyDocument15 pagesReport On Nuclear EnergyAmin FarukiPas encore d'évaluation

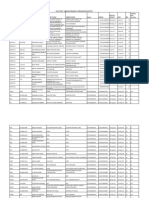

- List of Category IV Members Registered in Membership Drive-II Part 2Document111 pagesList of Category IV Members Registered in Membership Drive-II Part 2ahmadPas encore d'évaluation

- Musharraf Era Reforms and EventsDocument9 pagesMusharraf Era Reforms and EventsWajahat ZamanPas encore d'évaluation

- Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq: Early LifeDocument21 pagesMuhammad Zia-ul-Haq: Early LifeXeenPas encore d'évaluation

- Dr. Abdul Qadeer Khan's Contributions and DownfallDocument5 pagesDr. Abdul Qadeer Khan's Contributions and DownfallQudsiya KalhoroPas encore d'évaluation

- Nuclear Program of PakistanDocument28 pagesNuclear Program of PakistanKjsiddiqui BablooPas encore d'évaluation

- A Pakistani Fifth Column - The Pakistani Inter-Service Intelligence Directorate's Sponsorship of TerrorismDocument14 pagesA Pakistani Fifth Column - The Pakistani Inter-Service Intelligence Directorate's Sponsorship of TerrorismDeod3Pas encore d'évaluation

- Arms Race in South Asia: A History of India's Nuclear ProgramDocument42 pagesArms Race in South Asia: A History of India's Nuclear ProgramWaleed KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- PDFDocument305 pagesPDFhsnrbPas encore d'évaluation

- DR Abdul Qadeer KhanDocument25 pagesDR Abdul Qadeer KhanamirnawazkhanPas encore d'évaluation

- DR A.Q KhanDocument6 pagesDR A.Q KhanRana JahanzaibPas encore d'évaluation

- Bloom Verbs Cognitive Affective PsychomotorDocument177 pagesBloom Verbs Cognitive Affective PsychomotorMaheen AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- DR Abdul Qadir KhanDocument6 pagesDR Abdul Qadir KhanUsama HassanPas encore d'évaluation

- JHA IndiaWentNuclear 1998Document18 pagesJHA IndiaWentNuclear 1998GNDU LabPas encore d'évaluation

- The Pakistan Cauldron Conspiracy, Assassination & InstabilityDocument353 pagesThe Pakistan Cauldron Conspiracy, Assassination & InstabilityFaysalirshad100% (2)

- English 4 Chapter 1 To 11 PDFDocument33 pagesEnglish 4 Chapter 1 To 11 PDFAlizay khanPas encore d'évaluation

- Heartland - 2008 01 The Pakistani BoomerangDocument110 pagesHeartland - 2008 01 The Pakistani Boomeranglimes, rivista italiana di geopoliticaPas encore d'évaluation

- Abdul Qadeer KhanDocument5 pagesAbdul Qadeer KhanKhizerKhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Image of Pakistan in The US Media Exploring News FramingDocument57 pagesImage of Pakistan in The US Media Exploring News FramingsunnivoicePas encore d'évaluation

- Opposite of Future Pasture (History PDFDocument210 pagesOpposite of Future Pasture (History PDFMeesum AbbasPas encore d'évaluation

- Musharraf Era: Martial Law, Reforms and Major EventsDocument9 pagesMusharraf Era: Martial Law, Reforms and Major EventsAteeb Akmal67% (6)

- DR AQ KhanDocument31 pagesDR AQ KhanTasleem100% (5)

- Pakistan's Nuclear Program and US CollusionDocument1 pagePakistan's Nuclear Program and US CollusionManish BishtPas encore d'évaluation

- Pakistan and Geo-Political Studies HSS-403: Bahria University (Karachi Campus) Final Assessment Assignment Spring 2020Document10 pagesPakistan and Geo-Political Studies HSS-403: Bahria University (Karachi Campus) Final Assessment Assignment Spring 2020Ali AhmadPas encore d'évaluation

- Course Reading ListDocument8 pagesCourse Reading ListA Lapsed EngineerPas encore d'évaluation

- Scientist and Important Personalities of PakistanDocument11 pagesScientist and Important Personalities of PakistanNimra KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- List of Category III Members Registered in Membership Drive PH-IIDocument1 463 pagesList of Category III Members Registered in Membership Drive PH-IIAbdullah EjazPas encore d'évaluation