Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Maxie Rose Cahill Alden Lee Cahill v. Hca Management Company, Inc., 812 F.2d 170, 4th Cir. (1987)

Transféré par

Scribd Government DocsCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Maxie Rose Cahill Alden Lee Cahill v. Hca Management Company, Inc., 812 F.2d 170, 4th Cir. (1987)

Transféré par

Scribd Government DocsDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

812 F.

2d 170

Maxie Rose CAHILL; Alden Lee Cahill, Appellants,

v.

HCA MANAGEMENT COMPANY, INC., Appellee.

No. 86-1049.

United States Court of Appeals,

Fourth Circuit.

Argued Dec. 10, 1986.

Decided Feb. 23, 1987.

Rehearing and Rehearing En Banc Denied March 31, 1987.

Harold L. Kennedy, III (Harvey L. Kennedy, Kennedy, Kennedy,

Kennedy and Kennedy, Winston-Salem, N.C. on brief) for appellants.

Thomas G. Smith (Marcus Wade Harold Mitchell, Mitchell, Teele,

Blackwell, Mitchell & Smith, Valdese, N.C., on brief) for appellee.

Before WINTER, Chief Judge, HALL, Circuit Judge, and BUTZNER,

Senior Circuit Judge.

BUTZNER, Senior Circuit Judge:

Maxie Rose Cahill and Alden Lee Cahill appeal the district court's entry of

judgment on a directed verdict for HCA Management Company, Inc. (HMC), a

subsidiary of Hospital Corporation of America. Because we conclude that HMC

may be vicariously liable under North Carolina law which governs this

diversity action, we vacate the judgment and remand for further proceedings.

* Mrs. Cahill alleges that she was admitted to Ashe Memorial Hospital for

surgery and that she suffered injuries from a venapuncture negligently

performed by a medical technician.

Ashe Memorial Hospital and HMC had previously entered into an agreement

under which HMC undertook to manage the hospital. Although Ashe Memorial

trustees retained full authority and ultimate control over the hospital, HMC had

authority and responsibility to conduct, supervise, and manage the hospital's

day-to-day operation. The agreement made HMC responsible for "[t]he hiring,

discharge, supervision and management of all employees of the hospital,

including the determination of the numbers and qualifications of employees

needed...." In addition, HMC issued the bills for hospital services and collected

accounts owed the hospital. HMC was also responsible for all quality control

aspects of the hospital's operation, including efforts to achieve a high standard

of health care.

4

The agreement provided that the administrator, controller, and director of

nurses were to be employees of HMC. All other employees were designated as

employees of Ashe Memorial. HMC was to pay them out of funds it collected

from patients. The agreement exonerated HMC from liability for the negligence

of the Ashe Memorial employees that HMC hired, supervised, and controlled.

Ashe Memorial agreed to indemnify HMC for liability resulting from an

employee's negligence. Ashe Memorial also agreed to name HMC as an

additional insured on its general and professional liability policies.

The district court ruled that HMC could not be held liable under the doctrine of

respondeat superior because Ashe Memorial Hospital and not HMC was the

employer of the technician.

II

6

North Carolina subscribes to the axiom that the right of supervision and control

imposes vicarious liability on a principal for the negligent acts of its agent

committed within the scope of his employment. Azzolino v. Dingfelder, 71

N.C.App. 289, 318-19; 322 S.E.2d 567, 586-89 (1984). The HMC-Ashe

Memorial agreement's designation of the technician as an employee of Ashe

Memorial does not foreclose application of this axiom. In Jackson v. Joyner,

236 N.C. 259, 72 S.E.2d 589 (1952), the court explained that because a servant

can have two masters, a surgeon should not be absolved from vicarious liability

for the negligence of the hospital's nurse who administered anesthesia under

the surgeon's supervision. The court said:

It is true [the nurse] was in the general employ of the hospital; nevertheless, on

this record it is inferable that [the nurse] stood in the position of a lent servant

who for the purpose and duration of the operation occupied the position of

servant of [the doctor].... And the rule is that where a servant has two masters, a

general and special one, the latter, if having the power of immediate direction

and control, is the one responsible for the servant's negligence.... The power of

control is the test of liability under the doctrine of respondeat superior.

236 N.C. at 261, 72 S.E.2d at 591.

Davis v. Wilson, 265 N.C. 139, 143 S.E.2d 107 (1965), on which HMC relies,

expressly distinguishes Jackson because of factual differences. In Davis

pathologists employed by a hospital were not liable under the doctrine of

respondeat superior for the negligence of a laboratory technician. Although the

pathologists supervised the work of the technician, both the pathologists and

the technician were under control of the hospital's director. Unlike the situation

in Jackson, the Davis technician was not lent to the pathologists. All were under

the common control of the hospital's director.

10

In this case, HMC was responsible for selecting and supervising the technician

who performed the venapuncture on Mrs. Cahill in an allegedly tortious

manner. Besides exercising its general duty of supervision, HMC supervised

the technician directly through the hospital administrator, who was an HMC

employee. Ashe Memorial neither selected the technician nor supervised his

work. Though Ashe Memorial was the technician's nominal employer, it lent

him to HMC, which had the "power of immediate direction and control" over

him. See Jackson, 236 N.C. at 261, 72 S.E.2d at 591. HMC will be liable if the

technician was negligent. The Ashe Memorial-HMC agreement may enable

HMC to claim indemnity from Ashe Memorial, but it cannot deny recovery to

an injured patient whose rights are firmly based on North Carolina common

law.

11

We vacate the judgment of the district court and remand for further

proceedings. The appellants shall recover their costs.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- People v. Siton Case DigestDocument4 pagesPeople v. Siton Case DigestAnronish100% (2)

- Act 355 Syariah Courts Criminal Jurisdiction Act 1965Document8 pagesAct 355 Syariah Courts Criminal Jurisdiction Act 1965Adam Haida & Co100% (1)

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Northern New Mexicans v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthern New Mexicans v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Coburn v. Wilkinson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesCoburn v. Wilkinson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Parker Excavating v. LaFarge West, 10th Cir. (2017)Document24 pagesParker Excavating v. LaFarge West, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Jimenez v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesJimenez v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Chevron Mining v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Document42 pagesChevron Mining v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Robles v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesRobles v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Selections of Arbitration A Judicial ReviewDocument16 pagesSelections of Arbitration A Judicial ReviewArham RezaPas encore d'évaluation

- Human Rights Law CasesDocument343 pagesHuman Rights Law CasesDia Mia BondiPas encore d'évaluation

- Fbla Bylaws PDFDocument2 pagesFbla Bylaws PDFKylePas encore d'évaluation

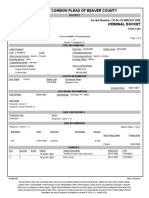

- Court of Common Pleas of Beaver County: Docket Docket Number: CP-04-CR-0002319-1996Document4 pagesCourt of Common Pleas of Beaver County: Docket Docket Number: CP-04-CR-0002319-1996sw higglebottomPas encore d'évaluation

- New Jurisprudence On Persons and Family Relations (Case Digests)Document11 pagesNew Jurisprudence On Persons and Family Relations (Case Digests)Monica Cajucom100% (3)

- Villanueva v. CADocument3 pagesVillanueva v. CAJoshhh rcPas encore d'évaluation

- Bayan V ErmitaDocument2 pagesBayan V ErmitaMarga Lera100% (1)

- Emusic CEO, Deadbeat Dad and Convicted Felon Adam Klein Faces Federal Workplace Sexual Harassment Lawsuit 2012-CV-5060Document36 pagesEmusic CEO, Deadbeat Dad and Convicted Felon Adam Klein Faces Federal Workplace Sexual Harassment Lawsuit 2012-CV-5060Christopher KingPas encore d'évaluation

- 05 China Banking Vs Asian Const r57Document12 pages05 China Banking Vs Asian Const r57Ryan SuaverdezPas encore d'évaluation

- Spouses Theis Vs CADocument3 pagesSpouses Theis Vs CAMariaPas encore d'évaluation

- Canlas v. CADocument10 pagesCanlas v. CATokie TokiPas encore d'évaluation

- Foreign CorporationsDocument18 pagesForeign CorporationsVinz VizPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals Fourth CircuitDocument2 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- 4 Apostolic Vicar of Tabuk v. Sps. SisonDocument1 page4 Apostolic Vicar of Tabuk v. Sps. SisonPam Ramos100% (1)

- I. General Principles: Nachura Notes - Local Government (Kiddy)Document34 pagesI. General Principles: Nachura Notes - Local Government (Kiddy)MarkB15100% (1)

- Sadhvi Pragya NIA Court Order 27 December 2017Document134 pagesSadhvi Pragya NIA Court Order 27 December 2017The QuintPas encore d'évaluation

- Lifting The Corporate VeilDocument25 pagesLifting The Corporate Veilburself100% (10)

- Fishing WaiverDocument1 pageFishing WaiverWendy Antos WinklerPas encore d'évaluation

- Ram Kumar PatelDocument3 pagesRam Kumar PatelAbhishekPas encore d'évaluation

- 92 Kayaban - v. - Republic20181112-5466-1scnm9dDocument4 pages92 Kayaban - v. - Republic20181112-5466-1scnm9dJaymie ValisnoPas encore d'évaluation

- Mutual NDADocument4 pagesMutual NDARetwik MukherjeePas encore d'évaluation

- Central Wyoming Law Associates, P.C., Formerly Hursh and Donohue, P.C., D/B/A Hursh, Donohue, & Massey, P.C., a Wyoming Professional Corporation v. The Honorable Robert B. Denhardt, in His Capacity as County Court Judge of Fremont County, Wyoming, and William Flagg, in His Capacity as County Attorney of Fremont County, Wyoming, and Those Acting Under His Direct Supervision, 60 F.3d 684, 10th Cir. (1995)Document6 pagesCentral Wyoming Law Associates, P.C., Formerly Hursh and Donohue, P.C., D/B/A Hursh, Donohue, & Massey, P.C., a Wyoming Professional Corporation v. The Honorable Robert B. Denhardt, in His Capacity as County Court Judge of Fremont County, Wyoming, and William Flagg, in His Capacity as County Attorney of Fremont County, Wyoming, and Those Acting Under His Direct Supervision, 60 F.3d 684, 10th Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Corpo - Villanueva BasedDocument16 pagesCorpo - Villanueva BasedJohn Ramil RabePas encore d'évaluation

- Contracts - GeneralDocument24 pagesContracts - GeneralandreaashleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Syllabus (November 2010)Document9 pagesSyllabus (November 2010)RZ ZamoraPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurisprudence ProjectDocument10 pagesJurisprudence ProjectVinay SheelPas encore d'évaluation

- WPI CASES For ReviewDocument122 pagesWPI CASES For ReviewMae Anne Sandoval100% (1)

- People V SultanDocument2 pagesPeople V SultanJude ChicanoPas encore d'évaluation